Abstract

Triclosan (TCS), a high volume chemical widely used in consumer products, is a known aquatic contaminant found in fish inhabiting polluted watersheds. Mammalian studies have recently demonstrated that TCS disrupts signaling between the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR), two proteins essential for excitation-contraction (EC) coupling in striated muscle. We investigated the swimming behavior and expression of EC coupling proteins in larval fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to TCS for up to 7 days (d). Concentrations as low as 75μg L−1 significantly altered fish swimming activity after 1d; which was consistent after 7d of exposure. The mRNA transcription and protein levels of RyR and DHPR (subunit CaV1.1) isoforms changed in a dose and time dependent manner. Crude muscle homogenates from exposed larvae did not display any apparent changes in receptor affinity toward known radioligands. In non-exposed crude muscle homogenates, TCS decreased the binding of [3H]PN200-110 to the DHPR and decreased the binding of [3H]-ryanodine to the RyR, demonstrating a direct impact at the receptor level. These results support TCS’s impact on muscle function in vertebrates further exemplifying the need to re-evaluate the risks this pollutant poses to aquatic environments.

Keywords: Triclosan, muscle contraction, calcium signaling, ryanodine receptor, dihydropyridine receptor

Introduction

Triclosan (TCS) is a high volume chemical incorporated in many consumer products for its antibacterial properties. In the United States, TCS was first introduced into deodorant in the 1960s, into the personal health care industry in 1972,1 and its worldwide usage is forecasted to continue to increase.2 Its broad product placement, daily household usage3 and inefficient removal during waste water treatment2, 4 have led to a prevalent occurrence in waterways around the world. Maximum levels in aquatic media have been reported at 2.3 Dg L−1 in surface water, at 53,000 Dg kg−1 in sediment samples5 and as high as 80 Dg ml−1 in the bile of wild caught fish species.6

Together with increased evidence of environmental exposures, there is mounting research showing that TCS may alter biological activities in eukaryotic organisms, leading to heightened concerns about its pervasive use.7 The antibacterial agent disrupts thyroid hormone pathways in anuran8-9 and mammalian species,9-10 and alters androgenic11 or estrogenic pathways in fish,12 indicating its potential for endocrine disruption. The pollutant also affects reproductive behavior13 and development in fish14-15 and alters xenobiotic metabolism in cellular based assays.1 The molecular mechanisms mediating these effects in higher organisms are not known, and are somewhat unexpected given that TCS hinders bacterial growth by inhibiting enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase, which is involved in bacterial fatty acid synthesis.16

We have recently shown that low nano-molar to micro-molar concentrations of TCS impair excitation-contraction (EC) coupling in skeletal and cardiac muscle by altering interactions between the L-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels on the T tubule membrane (i.e., dihydropyridine receptors; DHPRs) and the Ca2+ release channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (ryanodine receptors, RyRs).17-18 DHPR-RyR interactions are an essential component of the calcium release unit (CRU) that coordinates EC coupling in both cardiac and skeletal muscle. These proteins are also broadly expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems where they contribute to complex biological processes including dendritic growth and activity dependent synaptic plasticity.19-21 In mammals22 and fish23 dysfunction of DHPR or RyR, or key CRU regulatory proteins, has been tied to several disease states causing abnormal skeletal or cardiac muscle contraction.

In addition to the direct effect of TCS on the DHPRs and RyRs in in vitro assays, we found that in vivo exposure decreased hemodynamics and grip strength in mammals and impaired swimming activity and predator avoidance in fish.18 Locomotion is considered a basis for complex behaviors in fish and when decreased could readily alter interspecies and intraspecies interactions.24 This includes a range of activities such as predator avoidance, feeding activity, schooling and courtship behaviors, and migration in anadromous or catadromous species. All of these processes contribute to the survival of individual fish, as well as influence reproductive success, ultimately leading to determinants of a healthy population.24

The idea that altered behavior can alter ecological fitness in fish has been suggested by numerous studies looking at a wide range of contaminants.25 To help identify early signs of distress due to pollutants, behavioral assessments are often best understood when studied in concert with physiological and molecular changes.26 The systems biology approach not only investigates modes of toxic action but may provide information regarding the ecological implications of altered physiological pathways.27-28 Exposure to the pervasive environmental contaminant TCS has been shown to alter fish swimming behavior;13, 18 however, how these changes correlate with direct impacts on proteins essential for EC coupling, have not been investigated.

To address concerns regarding ongoing detection in aquatic environments we investigated whether TCS alters swimming performance and ability in an ecologically relevant fish species, the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), and whether behavioral impairments correlate with altered mRNA and protein expression of genes known to be critical for physiological EC coupling. In vitro receptor-based assays were employed to assess direct impacts of TCS on the functional state of DHPR and RyR in this model fish species. The fathead minnow was chosen for this work because it is widely used in ecotoxicology research, due to its ease of culture29-30 and well defined life history.29 The extensive research conducted to date in the minnow has shown it to be an important model for cross species and laboratory to field based extrapolations.29 Together these characteristics make it an ideal model for assessing the impact of the commonly detected environmental contaminant with unknown effects on fish muscle function.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Model Organism

Triclosan was purchased from the Fluka Chemical Corporation (Milwaukee, WI; CAS: 3380-34-5; 97% purity) and fathead minnow were obtained from Aquatox Inc. (Hot Springs, AR). All stock solutions of triclosan were created in 100% methanol at 10,000 fold concentrations of the ultimate exposure solution. During exposure 100μl of stock were subsequently added to 1L of dilution water so that methanol never exceeded 0.01%.

1.0 Triclosan Exposures in Larval Fish

Exposures were conducted following standard USEPA guidelines31 and larvae were 7 days post hatch (dph) at test initiation. During all tests, exposure water was created daily and approximately 80% of the treatment water was exchanged at which time survival and water parameters (pH, dissolved oxygen, and temperature) were monitored and dead fish removed. Triclosan concentrations were not directly measured in exposure solutions and are listed as nominal concentrations throughout. We were interested in a timed response and therefore limited our exposures to early onset of toxicity, (within 7 days of exposure).

Preliminary acute lethality tests were conducted with 7dph larvae exposed for 7 days (d) to 3-250 μg L−1 TCS, dissolved in 0.01% methanol, in order to determine suitable sublethal concentrations for further testing. The calculated lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC; Table S1), for survival after 7d of exposure, was 150 μg L−1. Subsequently, treatments of 10, 75, and 150 μg L−1 TCS were chosen as the low, medium and high exposure levels respectively. Larvae (7dph) were exposed for 1, 4 or 7d to dilution water, 0.01% methanol, or 10, 75, and 150 μg L−1 nominal TCS dissolved in 0.01% methanol. At test end, fish were randomly assigned to groups for behavioral assessments (n=12), gene transcription analysis (n=12), or protein analysis (90 fish pooled into three replicates of 30; n=3). Fish utilized for swimming assessments were directly placed into swimming apparati and fish designated for molecular work were euthanized with Tricaine methanesulfonate, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

1.1 Swimming Analysis

Fish were assessed for non-provoked swimming activity monitored by an overhead mounted camera and videos analyzed for total distance traveled, within 80 sec, using Ethovision Behavior Software (Noldus Information Technology). Following video recording, fish were assessed for feeding ability where the number of Artemia nauplii consumed in 3 min was visually monitored. Special care was taken to avoid the effect of time of day or prey density on the measured swimming parameters (Supplementary Information Section 2).

1.2 Gene Transcription

Total RNA was extracted from individual whole larvae utilizing TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Concentrations of RNA along with 280/260 and 260/230 ratios were determined on a Nanodrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific) and quality of RNA visualized on an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Subsequently, 1μg of total RNA was utilized to synthesize complementary DNA using Random Primers and SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase III (Invitrogen).

Genes of interest (Table 1) included the three main RyR isoforms found primarily in skeletal muscle (RyR1), cardiac muscle (RyR2), and neuronal tissue (RyR3) and the major DHPR subunit CaV1.1 found in skeletal muscle (CaV1.1). Genes were measured through quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) following previously described work.32 Unknown genes of interest were acquired through the use of degenerate primers designed from conserved regions gathered through multiple sequence alignments (ClustalW). Gene fragments, amplified by PCR using degenerate primers, were run on a 1% agarose gel, and appropriately size bands excised and cloned using a TOPO-TA Cloning Kit® (Invitrogen). Purified plasmids were sequenced at the UC Davis sequencing facility at the College of Biological Sciences and submitted to the NCBI databank. For isoform specific genes, i.e. RyR 1, 2 and 3, primers were designed within regions that differ between known full sequences in other fish species (D. rerio) and the resulting amplicons were confirmed as isoform specific using BLAST.

Table 1.

Genes Investigated For Triclosan Induced Changes in mRNA levels

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol |

Accession Number |

Primer Sequence (F/R) | Probe No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryanodine Receptor, 1 | RyR1 | * | AAGATGACGATGAAGGGTTTGTC CATGGCAGGTTCCATATATCCAG |

65 |

| Ryanodine Receptor, 2 | RyR2 | JF696948† | CCACCTTCTCGAGGTCAGGTT CCGCCTCAGTGACGGATAATAA |

21 |

| Ryanodine Receptor, 3 | RyR3 | * | GTCAGGAGTCGTACGTGTGGAA ACTGGTCCTCATACTGCTTACGG |

159 |

| Selenoprotein N, 1 | SEPN1 | * | TGCCACCCAGTGGTAAATCTG GGTTATTGGGAAGGTAGCCAGTG |

138 |

| Dihydropyridine Receptor, (subunit CaV1.1) |

CaV1.1 | JF696952† | GATTCTCAGGGTGTTGAGGGTACT CACTGGACCACGTGCTTTAACC |

147 |

| FK506 Binding Protein |

FKBP12 | JF696949† | TGTTTGAGCATGCCGTGAAC CTCTTAAGCCAGAGCAGTTTTGC |

18 |

| Junctophillin1 | JPH1 | JF696950† | GCTGTTCGGGAGCCTCAAG ATCGCTAGAGCTTATGCGGCT |

25 |

| Homer 1 | h1 | JF696954† | CTTGCACACAGCCCGACTAC GCACTGTGAGCTTGGCATTGT |

48 |

| Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Calcium ATPase |

SERCA1 | JF696953† | CAACATTGGCCACTTCAACG GAGCCACAGCGATCTTFAAGT |

92 |

| Creatine Kinase | CK | * | GAGAGGCCAGAAGGATTCTTGA CCTTGAACACCTCATAGGCTCTTC |

5 |

| β-actin | β-actin | EU195887 | CAACACCGTGCTGTCTGGAG TCTTTCTGCATACGGTCAGCAA |

157 |

| L8 ribosomal protein | L8 | AY919670 | GGCTAAGGTGGTTTTCCGTGA CTTCAGCTGCAATGAACAGCTC |

35 |

| Elongation Factor 1-alpha |

EF1α | AY643400 | CTCTTTCTGTTACCTGGCAAAGG TCCCATGATTGATTAGTTTCAGGAT |

66 |

Sequences supplied by N. Denslow, UFl

Sequences identified in this study

1.3 Protein Level Assessments

Crude membrane protein preparations were obtained following procedures published elsewhere33-34 and protein concentrations determined through a BCA assay (Pierce). Protein, 10 g of each homogenate, was resolved on a 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies) and blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies; anti-mouse RyR1 (1:1000, 34C, DSHB), anti-rabbit Phospho-Serine 2808 (1:2000, AbCam; analogous to RyR1 phospho-Serine 2843),35 anti-mouse CACNA1S (1:500; CaV1.1, mAb1, AbCam) and anti-rabbit GAPDH (1:2000, Cell Signaling). Bands were subsequently detected with a goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to fluorescent dyes (DyLight™ 680 or 800, respectively) and visualized and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR).

Protein preparations were also utilized to investigate receptor affinity for known radioligands post exposure. Changes in the DHPR were assessed using [3H]-PN200-110 ([3H]PN; Perkin Elmer), a known antagonist to L-type Ca2+ channel currents,36 while changes in the RyR were assessed using [3H]-Ryanodine ([3H]Ry; Perkin Elmer), which preferentially binds to the open state of RyR channels.37 Differences were assessed, for each radioligand separately, and due to limited material, were assessed at only one radioligand concentration near the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd). This information was determined in this study using adult skeletal crude membrane preparations as described under the supplementary information (Figure S1). Exposed larval homogenates were incubated, near the determined Kd for the given receptor (10nM [3H]PN or 20nM [3H]Ry). For [3H]PN binding, samples were incubated for 2h at 25°C in the dark and for [3H]Ry binding samples were incubated for 16h at 25°C. After incubation, binding reactions were quenched by filtration through glass fiber filters and bound radioligand measured by liquid scintillation counting (model LS6500; Beckman). Non-specific binding was determined with the addition of 50 μM nifedipine or 20 μM ryanodine and 200 μM EGTA.

2.0 Direct Impact on the RyR and DHPR

Receptor effects were determined using membrane homogenates prepared from the skeletal muscle of non-exposed adult fathead minnow or whole larvae as previously described.33-34 This design allowed for increased test replication and for sensitivity assessments between different age groups. Radioligand receptor binding analysis was performed in the presence of 0.1% DMSO or 0.1-40 μM (30-11,582 μg L−1) TCS dissolved in 0.1% DMSO. Effects on the DHPR were performed by incubating with 5 nM [3H]PN for 1h at 25°C in the dark. Effects on the RyR were assessed in the presence of 10 nM [3H]Ry incubated for 16h at 25°C. Non-specific binding was determined with the addition of either 50 μM nifedipine or 10 μM ryanodine and 200 μM EGTA. After incubation samples were quenched through a glass fiber filter and bound radioligand measured by liquid scintillation counting.

3.0 Statistical Analysis

Postexposure statistical assessments were completed utilizing a multi-factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and differences between TCS treatments and the methanol control determined using a Dunnett’s post hoc analysis (Minitab 16.0;State College, PA). Direct impacts on the DHPR and RyR in nonexposed protein homogenates were determined using sigmoidal-dose response curves or a oneway ANOVA (Prism 5.0; Graphpad Software).

Genes β-actin, EF1-α, and L8 were determined to be the most stable across the dose and time treatment structure from this experiment. Genestability (M) was determined using the geNorm® algorithm following the methods outlined by Vandesompele et al. (2002) and subsequently each gene of interest was normalized to the calculated normalization factor for the selected references genes.38 Values were placed on a log-2-scale for parametric statistical testing and then compared to the control from their respective time point.

To compare molecular expression data with swimming parameters and survival, patterns in mRNA transcription were discerned through Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and factors with eigenvalues above one were considered to significantly explain variation in the data. Genes underlying the given variability were then clustered using a K-Means Cluster analysis (Genesis® Software; Graz University of Technology). For protein, only RyR1 or CaV1.1 were overlapped on graphs depicting responses after 1d or 7d of exposure respectively. At 4d of exposure both proteins showed similar patterns in response (see Results); therefore, protein intensity was averaged.

Results and Discussion

1.0 Triclosan Impairs Swimming Performance

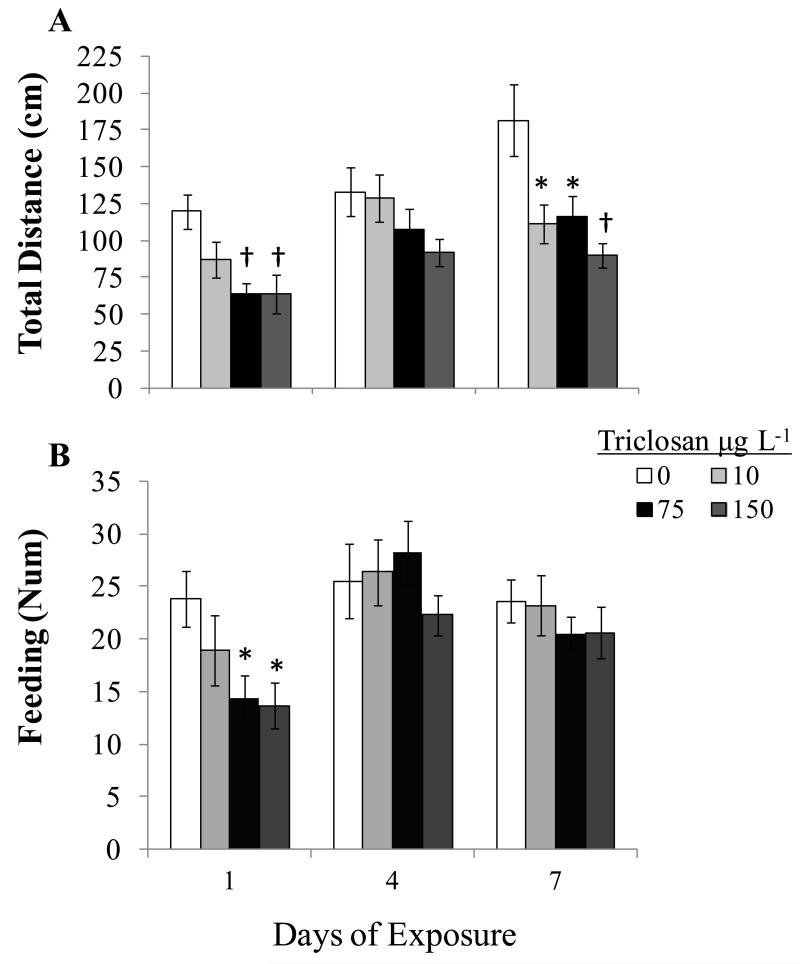

Throughout larval exposures, water quality parameters remained consistent with USEPA guidelines (mean ±SEM; dissolved oxygen = 7.48 ± 0.15 mg L−1, electrical conductivity = 284.65 ± 2.49 μS, pH = 7.69 ± 0.03 and temperature = 22.55 ± 0.34°C).31 The observed impact on swimming behavior occurred far below the 7d calculated LOEC and LC50, 150 and 190 μg L−1 respectively (Table S1). For both swimming and feeding assessments, there was not an interaction between time of exposure and treatment concentration, as determined through a multi-factorial ANOVA (total distance and feeding; p=0.283 and p=0.416 respectively), suggesting that TCS’s effects on swimming and feeding ability (Figure 1) were consistent across the monitored time points. The main effect of TCS, regardless of time, demonstrated that levels, as low as 10 μg L−1, lead to significant decreases in swim activity as measured by total distance traveled (p<0.001). Effects of TCS on feeding ability resulted in a downward trend but the observed impact did not reach significance (p=0.072). When effects, on swimming activity, were visualized at the different exposure periods the downward trend was consistent across time points (Figure 1A). For feeding ability, there appeared to be an immediate strong impact after just 1d, which was not as pronounced after 4 and 7d of exposure (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Time dependent impact of triclosan on the swimming (A) and feeding (B) activity of larval fathead minnow. Means ± SEM, n=12. Significance between triclosan treatments and the control were determined through a one-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnetts’ post hoc analysis compared to the solvent control. * p<0.05, † p<0.01.

1.1 Triclosan Alters the Transcription of CRU related Genes

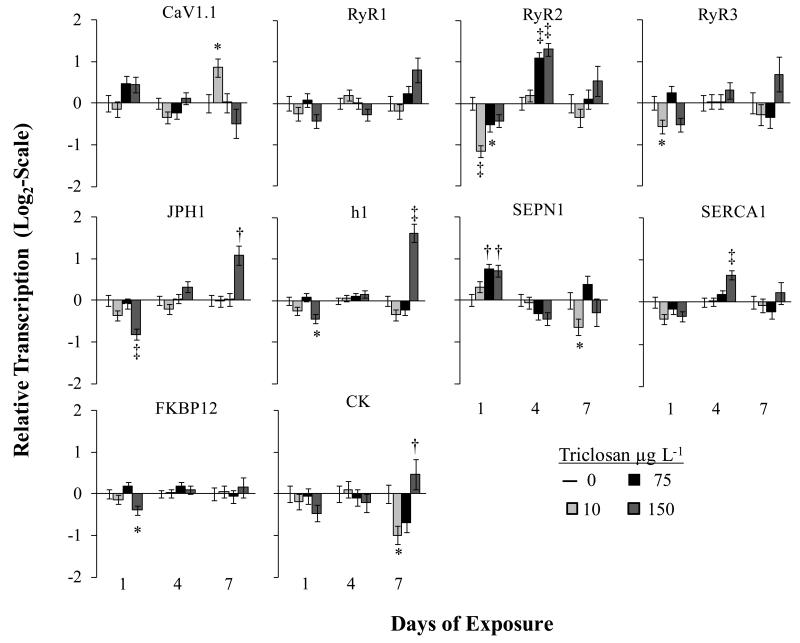

Genes transcript levels changed in a dose and time dependent manner (Figure 2), as determined through a multi-factorial ANOVA. Transcription of the voltage-sensitive subunit of the DHPR, CaV1.1, was impacted after just 1d, where higher TCS concentrations led to increased mRNA levels (p<0.05; unresolved by a Dunnett’s), followed by return to control levels after 4d (p<0.156), and a significant increase at lower concentrations after 7d (p<0.01). Previous research has shown that TCS has a direct effect on the DHPR in skeletal muscle which would contribute to altered muscle performance or swimming ability. Changes in mRNA transcription in TCS exposed organisms may represent a stress response as a way to maintain homeostasis in muscle function.

Figure 2.

Time dependent and dose dependent changes in mRNA transcription in triclosan exposed larval fish. Numbers are LSMeans ± SEM, n=11-12, except 150 μg L−1 which due to altered survival and the number of endpoints investigated only had n=4. Significance is shown relative to the control for the respective time-point. * p≤0.05, † p≤0.01, ‡ p≤0.001. Abbreviations: Ryanodine Receptor isoforms 1,2 3 (RyR 1-3); Dihydropyridine Receptor, subunit1αS, (CaV1.1); Selenoprotein N1 (SEPN1); Junctophilin 1 (JPH1); Homer 1 (h1); Sacro/Endoplasmic reticulum ATPase (SERCA), FK-Binding Protein 12 (FKBP12); Creatine Kinase (CK).

There was a drastic impact on RyR2 found in cardiac tissue. Transcription of RyR2, was decreased after 1d (p<0.05 and p<0.01), increased at 4d (p<0.001), and similar to controls by 7d of exposure (p=0.212). The decrease in RyR2 after 1d and subsequent increases after 4d of exposure suggests that TCS has a strong impact on cardiac function; supporting findings of TCS induced cardiac impairments in mice.18 Transcription of RyR1 and RyR3 rarely showed significant changes compared to the methanol control. Transcription of SERCA1, an ATPase pump, which is responsible for refilling the Ca2+ store in the SR following muscle contraction, displayed significant increases in transcript levels at higher concentrations after 4d of exposure.

Accessory proteins which maintain the position or close cellular coupling of DHPR-RyR or which regulate the activity of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release were also altered by TCS exposure. This included increases in the transcription of SEPN at higher concentrations after just 1d of exposure. Selenoprotein N (SEPN) physically interacts with the RyR1 and is known to regulate the activity of the receptor during periods of redox stress and has a demonstrated role in muscle development.39-41 The transcription of JPH1 and h1 were significantly decreased after 1d and significantly increased after 7d exposure to 150 μg L−1 TCS. Both JPH1 and h1 are important for maintaining conformational coupling between the DHPR and RyR. For example, in skeletal muscle and neurons JPH1 is essential for maintaining the RyRs close association with proteins in the plasma membrane (e.g. DHPR).19 Transcripts of FKBP12, an accessory protein critical for stabilizing the closed conformation of RyRs, showed little change across treatments at all time points. In mammalian studies it was shown that TCS disturbed EC-coupling through a mechanism requiring both CaV1.1 and RyR1.18 The direct site of TCS’s action on the two receptors has not been elucidated. Future studies addressing TCS’s impact on cellular redox potential or the interaction of JH1 and h1 proteins, with the receptors, might further elucidate TCS’s impact on EC-coupling.

Transcription of CK was significantly decreased by lower TCS concentrations after 7d (p<0.05). Creatine kinase is an enzyme responsible for breaking down phosphocreatine molecules to supply phosphorous for sustained ATP production in high energy demand tissues such as striated muscle or neurons. Altered CK protein levels, enzyme activity, and transcription have been used for markers of skeletal or cardiac disease states including a number directly related to the RyR and Ca2+ signaling.42 The increase in CK expression further supports damage to the CRU in TCS exposed larval fish.

1.2 Triclosan Alters DHPR and RyR Protein Expression

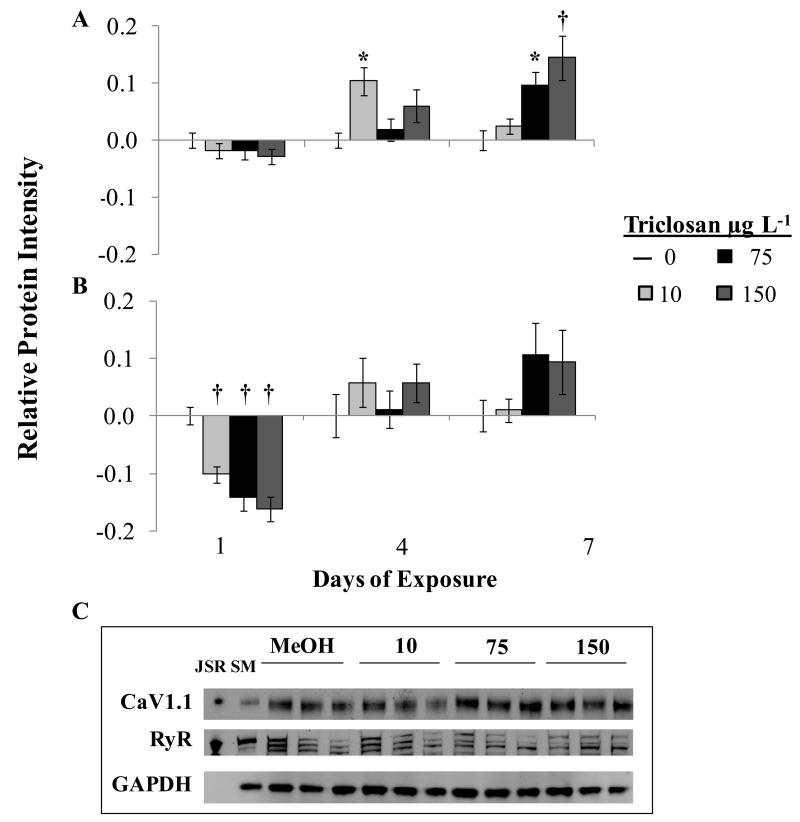

In homogenates from TCS exposed larvae, monoclonal antibody CACNA1S (CaV1.1 of the DHPR) identified a single band at ~172kDa, consistent with previous studies,43 and antibody 34C binds to three distinct bands located in the RyR region (562kDa), a result consistent with the expression of three RyR isoforms (Figure 3). To date, work performed in other species has shown that fish skeletal muscles have two paralogous RyR1 isoforms,33, 44 expressed in either oxidative red (RyR1α) or glycolytic white (RyR1β) muscle, as well as RyR3 primarily found in white muscle, supporting the three isoforms found in this study.33, 44 These isoforms have been shown to vary slightly in size;33 therefore, the band mobility order in Figure 3 is presumably RyR1β, RyR1α and RyR3. These bands probably do not represent the cardiac RyR isoform, RyR2, as the monoclonal antibody 34C did not recognize bands in adult fathead minnow heart preparations, even at antibody levels as high as 1:200 (data not shown). For quantification, all three bands were measured together and protein intensity normalized to the loading control GAPDH.

Figure 3.

CaV1.1 (A) and Ryanodine Receptor (B) protein levels in larvae exposed to triclosan for up to 7d. Numbers represent Means±SEM; n=3. Band intensity was normalized to GAPDH intensity and then subtracted by the control level by gel (2-4 per time point). The fluorescent intensity readings of all three RyR bands were considered together. Normalized values were then averaged across the three samples per time point, Means±SEM. * p≤0.05, †p≤0.01 (C) Representative band separation visualized on 10 gels. Abbreviations: Rabbit skeletal muscle Junctional Sarcoplasmic Reticulum preparation (JSR); Adult fathead minnow skeletal muscle preparation (SM); Sample preparations from larvae exposed to 0.01% Methanol (MeOH) or 10,75 or 150 μg L−1 TCS.

As seen with the mRNA data, protein levels demonstrated a time and dose dependent changes in relative expression (Figure 3). There was a significant increase (p=0.001) in CaV1.1 protein in fish exposed to 75 or 15 0μg μg L−1 after 7d and a significant decrease (p<0.001) in RyR protein levels observed after only 1d; which was apparent at all TCS concentrations. There was a trend toward increased RyR protein quantities in those fish exposed for 7d but these findings did not reach significance (p=0.073). The phosphorylation of RyR at S2808 (analogous to RyR1 S2843; which aligns with S2866 or S2883, in Danio rerio and Makaira nigricans RyR1 sequences respectively; BLAST), a site debated to influence RyR activity in skeletal muscle disease,39 was assessed in all protein samples. There was not a significant difference in the level of RyR phosphorylation across the treatments groups, at any time point, suggesting that phosphorylation at Ser2808, does not mediate TCS’s impact on the receptors function (Figure S2).

Changes in RyR and DHPR receptor density and affinity were assessed using high affinity radioligand-receptor binding analysis in exposed larvae. For both [3H]Ry and [3H]PN there was not a significant difference in the amount of radioligand binding in larvae exposed to different TCS treatments at the three time points (Figure S3) suggesting that exposure did not alter the apparent affinity of these receptors for their respective ligands.

Muscle performance and contraction, a strong indicator of locomotor performance,45 can be impacted by a number of processes including both extrinsic (e.g. oxygen availability due to cardiac output) and intrinsic (e.g. cellular metabolism) factors. Both cardiac46 and skeletal muscle45 contraction are strongly impacted by Ca2+ handling dynamics coordinated by the DHPR, RyR and SERCA and it has been shown that altering protein expression or activity of these key proteins can lead to altered power output and decreased fatigue resistance in isolated skeletal muscle cells in teleost and mammalian species.45, 47-48 These impacts at the cellular level are directly associated with altered swimming speed and fatigue resistance in whole-animals creating a direct connection between altered Ca2+ signaling and altered fish locomotion.23, 45 Therefore, changes in DHPR or RyR protein levels in TCS exposed fish may represent altered cellular function contributing to altered swimming performance.

2.0 Triclosan has a Direct Impact on the DHPR and RyR in Fathead Minnow

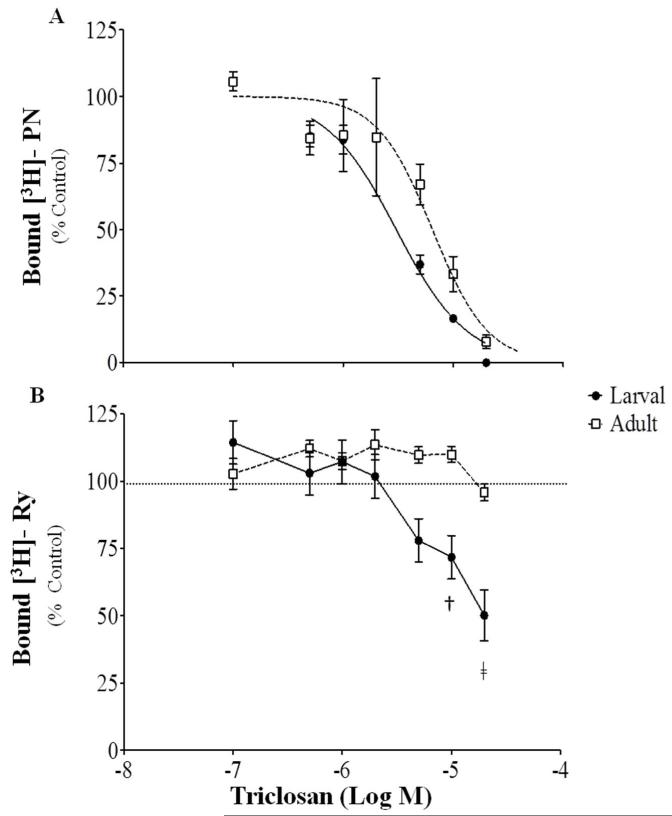

Recent work has shown that TCS directly alters the binding of [3H]PN and [3H]Ry to the DHPR or RyR channels respectively.17-18 Radioligand-receptor binding assays performed with naive (i.e. non-exposed) fathead minnow whole larvae or adult skeletal muscle homogenates revealed that, consistent with result from mammalian preparations, TCS inhibits the binding of [3H]PN to DHPR (Figure 4A; 95% CI; IC50= 2.45-3.78 or 4.83-8.70 μM for larval and adult preparations; respectively). The IC50 values obtained with larval and adult fish preparations were significantly different (p=0.002). Preliminary results obtained from larval and adult homogenates indicated that TCS is an allosteric inhibitor of [3H]PN binding (Figure S4), which is consistent with results obtained with preparations from mammalian skeletal muscle.18

Figure 4.

Radioligand binding in larval fish and adult skeletal muscle homogenates in the presence of triclosan. (A) [3H]-PN200-110 ([3H]-PN) specific binding shown as a percentage of a DMSO control, Means ± SEM, n=3; (B) [3H]-Ryanodine ([3H]-Ry)specific binding shown as a percentage of a DMSO control, Means ± SEM, n=10-13, blocked across 4 different tests. Both curves for [3H]-PN were assessed through a sigmoidal dose response. Effects on [3H]-Ry were assessed through a one-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett’s post test compared to the DMSO control. † p≤0.01, ‡ p≤0.001.

Effects of TCS on [3H]Ry binding in whole larvae and adult preparations differed (Figure 4B). In naive whole larval homogenates TCS concentrations greater than 5 μM had an inhibitory impact on [3H]Ry binding which was not seen in adult preparations even at concentrations as high as 2 0 μM. There was a slight elevation in [3H]Ry binding in adult preparations at lower concentrations but these differences were not significant. The presence of all RyR isoforms (ie. RyR1, 2, and 3) in whole larvae homogenates could explain the observed differences in binding as adult preparations consisted of skeletal muscle, containing RyR1. The significant inhibitory effect seen in larvae are in contrast to the direct impact of TCS documented in mammalian systems, where TCS enhanced [3H]Ry binding in both rabbit and mouse skeletal muscle preparations.17-18 This may suggest that fish RyRs are more sensitive to TCS’s inhibitory actions. The RyR1 in fish species is slightly larger in size and displays approximately 72% sequence homology with that found in mammals.33 Amino acid sequence differences33, 44 between vertebrate classes could explain our results, which is supported by evidence that sensitivity to RyR inhibition by the plant alkaloid ryanodine is highly variable across teleosts and far less than in mammals.49 In comparison to mammals, fish RyR1 contain several unique calmodulin-dependent protein kinase regulatory sites, nucleotide binding sites, and lack the “EF hand“ like motifs. The EF-motifs have been hypothesized to be the site for Ca2+binding and regulation;33 however, site directed mutation analysis of these domains have not supported their role in Ca2+ regulation of the RyR1 channel.50 The direct molecular site of TCS’s interaction with the RyR has yet to be elucidated but these unique sites may confer potential amino acids of interest.

3.0 Overlapping Changes in Swimming Performance with Changes in CRU Related Molecular Biomarkers

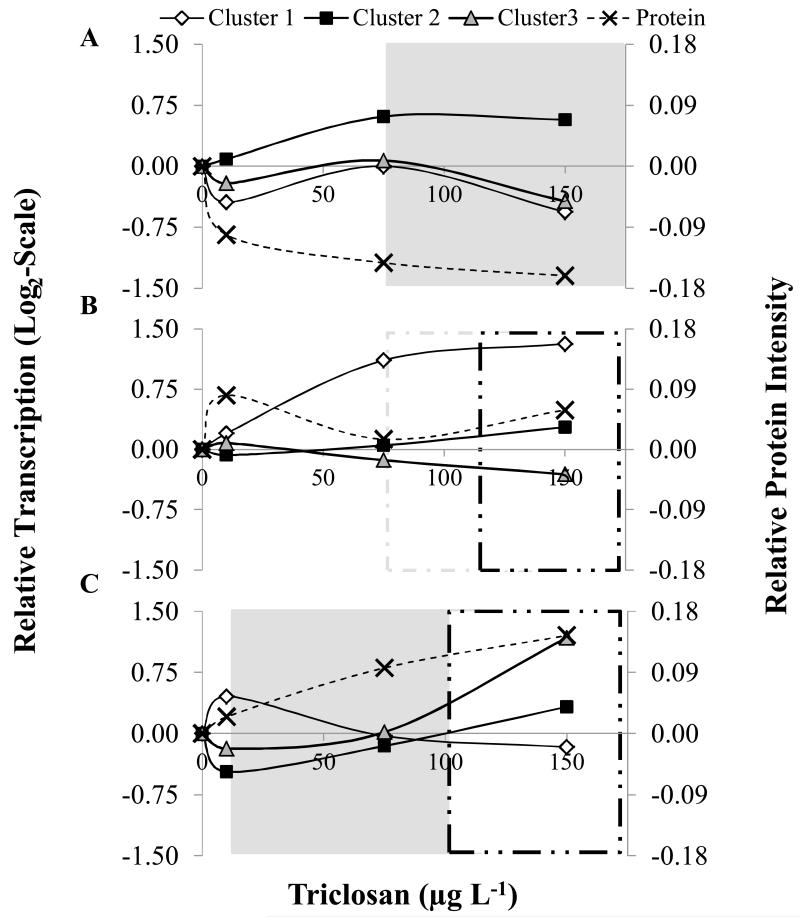

Since both mRNA transcripts and protein profiles for CaV1.1 and RyR appeared to vary concordantly with dose and length of exposure, we investigated whether these changes were associated with the severity of behavioral impairments. We overlapped patterns in mRNA and protein with the concentration at which swimming was significantly affected (Figure 1) or at which lethality was projected to 10% of the population (LC10; Table S1) (Figure 5). For mRNA, patterns were condensed using a PCA per time point, which discerned three factors, with eigenvalues above one which adequately explained at least 66% of the variability in larval fish responses. Genes ascribed to each factor were varied by time point (see Figure 5). The expression of CaV1.1 or RyR1 protein also varied by time point where only RyR1 responded at 1d, neither at 4d, and only CaV1.1 at 7d.

Figure 5.

Molecular and whole organism responses of larval fathead minnow exposed to triclosan for up to 7d. Proposed areas of compensation (Clear); periods of physiological stress (Significant effects on swimming; gray shaded), concentrations known to cause lethality in 10% of the exposed individuals (Black–..–) and Gray (–..–) represents a decreased trend in swimming at 4d. Day 1, (A) Cluster 1 included RyR1, RyR3, SERCA1, and JN1; Cluster 2 included SEN1 and CaV1.1 Cluster 3 included RyR1, FKBP12, h1, and CK, Protein RyR only; Day 4, (B) Cluster 1 included RyR2; Cluster 2 included RyR3, CaV1.1, FKBP12, JN1, h1, and SERCA1; Cluster 3 included RyR1, SEPN and CK, Protein average RyR and CaV1.1; Day 7, (C) Cluster 1 included CaV1.1 and FKBP12; Cluster 2 included RyR2, RyR3, SEN1, SERCA1, and CK; Cluster 3 included RyR1, JN1, and h1, Protein CaV1.1 only. Lines were added purely for visualization of patterns.

Looking at each time point independently, TCS exposed larvae displayed a non-monotonic dose response curve where differences in mRNA transcription were up or down-regulated at low concentrations followed by an inflection in response at high concentrations. On the other hand protein levels often displayed a dose dependent response followed by a plateau stage (Figure 5). Here, especially at earlier time points, and at lower TCS concentrations, it is hypothesized that the fluctuations represent a regulatory response for pathways that are impacted by TCS in an effort to return to homeostasis. This response shifted by length of exposure, as has been described in other studies addressing the time dependent effects of other chemicals.51-54 These findings demonstrate the need to assess chemical impacts at early time-point directly following exposure initiation.

It has been suggested by other works that an inflection or plateau in a molecular response represents a point at which physiological stress, such as swimming behavior, would be evident.55 In the present study, inflections in molecular responses often overlap with changes in swimming behavior or survival by exposure time supporting this hypothesis. For example, after 1d of exposure, lower concentrations of TCS caused a decreased overall molecular response but once levels reached 75 μg L−1 mRNA transcription patterns changed, which overlapped with changes in swimming performance. This overlap was even more pronounced at exposure day 7, where the fish’s swimming behavior was significantly impacted at 10 μg L−1 and significant mortality occurred above 101 μg L−1 (Calculated LC10; Table S1). Further research addressing molecular patterns at even lower TCS concentrations would be valuable in order to fully understand responses after 7days.

Levels of TCS, similar to those reported in the environment, (3 μg L−1 exposure56 versus 2.3 μg L−1 US maximum5) have been shown to accumulate in fish where steady state is achieved within one week and substantial contaminant loads detected in both muscle and brain tissue post exposure.56 Tissue levels were not analyzed in this study; however, TCS exposures as low as 10 μg L−1 were found to alter larval fish locomotion. These results are consistent with recent findings by Cherednichenko (2012)18 which utilized similar parameters to compare TCS’s impact on larval fish performance and are supported by trends observed elsewhere.13 Taken together this demonstrates that TCS alters key physiological processes important for locomotion and has the potential to impact individuals exposed in the environment.

We demonstrated that TCS induced changes in physiological performance corresponded with changes in CRU gene transcription and protein level expression. Additionally, it was demonstrated that TCS has a direct impact on the key receptors in the CRU, namely the DHPR and the RyR. These findings support Ca2+ signaling disruption as a mechanism of TCS induced toxicity in vertebrates. In fish, high and low performing swimmers have been shown to display different mRNA levels in their skeletal muscle for DHPR, RyR1, and SERCA1.23, 45 These genes may act as valuable biomarkers for altered CRU pathways due to TCS and other contaminants exposures in an environmentally relevant setting.

The physiological mechanisms behind altered swimming performance or behavior involve several pathways, a number of which are potentially impacted by TCS. In particular, TCS acts as an endocrine disrupting compound known to alter thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) in exposed rats and altered thyroid hormone mediated mRNA translation in anuran in vitro assays.9 In exposed fish species, TCS was shown to induce vitellogenin, a biomarker for altered estrogenic pathways.12 Both thyroid hormones57-58 and estrogen related compounds59 are known to regulate Ca2+ signaling, in mechanisms involving CRU related proteins, and the CRU plays a role in hormone secretion.60-61 Utilizing a systems approach to address altered endocrine signaling in TCS exposed fish, and how they related to the observed CRU functional differences discussed herein, would provide great insight into the connection between these convergent pathways.

The effects of TCS on the fathead minnow were dependant on both time of exposure and dose. We monitored impacts up to 7d, a partial life-cycle endpoint,29 and utilized concentrations above what are often documented in waterways.5 It should be noted however that concentrations above 50,000 μg kg−1 have been found in sediment and it is estimated that levels in pore water reach 382 μg L−1.5 Additionally, levels in surface water may vary greatly with distance to effluent outfall as evidenced by increasing concentrations in biota closer to wastewater treatment plants.62 Organisms may be exposed to slightly lower levels of TCS than utilized in this study, however, periods of exposure are likely continual creating greater exposure risk in impacted waterways.

Given the wide spread occurrence of TCS in all forms of environmental media5 and the fact that it is present in complex mixtures63 exemplifies the need to conduct further risk assessment regarding threats posed in aquatic ecosystems. Calcium signaling is a major contributor to a long list of physiological processes, a number of which are directly connected to the RyR and DHPR. Altering this key pathway could not only disrupt muscle function, and its resulting behavioral impacts, but could have drastic impacts on fertilization, endocrine regulation, and the development and function of major organ systems.64

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The UC Davis NIEHS Superfund Research Program P42 ES004699 supported this project (to INP and EBF). Additional Support came from NIEHS 1R01-ES014901 and 1R01-ES017425. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health. Partial support was provided by the Interagency Ecological Program, Sacramento, Ca (No. 46000008070; IW and R10A20097; REC) and the UC Davis Pharmacology and Toxicology Graduate Group. Appreciation is extended to members of the Aquatic Health Program (former Aquatic Toxicology Laboratory), UC Davis, who assisted with test procedures and design, to Dr. Swee Teh for use of laboratory space, and to Dr. Nancy Denslow, University of Florida, for supplying several gene sequences important to this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information Available Detailed methods description, acute lethality results (Table S1), the radioligand saturation data for [3H]PN and [3H]Ry (Figure S1), RyR phosphorylation at S2808 (S2843; Figure S2) in exposed larvae, changes in radioligand binding in exposed larvae (Figure S3), and allosteric inhibition of CaV1.1 by TCS in larval and adult fathead minnow (Figure S4). This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Wang L-Q, Falany CN, James MO. Triclosan as a substrate and inhibitor of 3′-Phosphophoadenosine 5′-Phosphosulfuate-Sulfotransferase and UDP-Glucuronosyl transferase in human liver fractions. Drug Metab. Disposition. 2004;32(10):1162–1169. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidler J, Halden RU. Mass balance assessment of triclosan removal during conventional sewage treatment. Chemosphere. 2007;66(2):362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodricks JV, Swenberg JA, Borzelleca JF, Maronpot RR, Shipp AM. Triclosan: A critical review of the experimental data and development of margins of safety for consumer products. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010;40(5):422–484. doi: 10.3109/10408441003667514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAvoy DC, Schatowitz B, Jacob M, Hauk A, Eckhoff WS. Measurement of triclosan in wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002;21(7):1323–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalew TEA, Halden RU. Environmental Exposure of Aquatic and Terrestrial Biota to Triclosan and Triclocarban1. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 2009;45(1):4–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2008.00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houtman CJ, van Oostveen AM, Brouwer A, Lamoree MH, Legler J. Identification of Estrogenic Compounds in Fish Bile Using Bioassay-Directed Fractionation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38(23):6415–6423. doi: 10.1021/es049750p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooney CM. Triclosan comes under scrutiny. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118(6):A242. doi: 10.1289/ehp.118-a242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhoen N, Skirrow RC, Osachoff H, Wigmore H, Clapson DJ, Gunderson MP, Van Aggelen G, Helbing CC. The bactericidal agent triclosan modulates thyroid hormone-associated gene expression and disrupts postembryonic anuran development. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006;80(3):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinther A, Bromba CM, Wulff JE, Helbing CC. Effects of Triclocarban, Triclosan, and Methyl Triclosan on Thyroid Hormone Action and Stress in Frog and Mammalian Culture Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(12):5395–5402. doi: 10.1021/es1041942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zorrilla LM, Gibson EK, Jeffay SC, Crofton KM, Setzer WR, Cooper RL, Stoker TE. The Effects of Triclosan on Puberty and Thyroid Hormones in Male Wistar Rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;107(1):56–64. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foran CM, Bennett ER, Benson WH. Developmental evaluation of a potential non-steroidal estrogen: triclosan. Mar. Environ. Res. 2000;50(1-5):153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0141-1136(00)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishibashi H, Matsumura N, Hirano M, Matsuoka M, Shiratsuchi H, Ishibashi Y, Takao Y, Arizono K. Effects of triclosan on the early life stages and reproduction of medaka Oryzias latipes and induction of hepatic vitellogenin. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004;67(2):167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz M, Bartell S, Schoenfuss H. Effects of Triclosan and Triclocarban, Two Ubiquitous Environmental Contaminants, on Anatomy, Physiology, and Behavior of the Fathead Minnow (Pimephales promelas) Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012;63(1):114–124. doi: 10.1007/s00244-011-9748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira R, Domingues I, Koppe Grisolia C, Soares A. Effects of triclosan on zebrafish early-life stages and adults. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2009;16(6):679–688. doi: 10.1007/s11356-009-0119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nassef M, Kim SG, Seki M, Kang IJ, Hano T, Shimasaki Y, Oshima Y. In ovo nanoinjection of triclosan, diclofenac and carbamazepine affects embryonic development of medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) Chemosphere. 2010;79(9):966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slater-Radosti C, Van Aller G, Greenwood R, Nicholas R, Keller PM, DeWolf WE, Fan F, Payne DJ, Jaworski DD. Biochemical and genetic characterization of the action of triclosan on Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48(1):1–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn KC, Zhao B, Chen J, Cherednichenko G, Sanmarti E, Denison MS, Lasley B, Pessah IN, Kültz D, Chang DP, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. In vitro biologic activities of the antimicrobials triclocarban, its analogs, and triclosan in bioassay screens: receptor-based bioassay screens. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116(9):1203–1210. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherednichenko G, Zhang R, Bannister RA, Timofeyev V, Li N, Fritsch EB, Feng W, Barrientos GC, Schebb NH, Hammock BD, Beam KG, Chiamvimonvat N, Pessah IN. Triclosan impairs excitation-contraction coupling and Ca2+ dynamics in striated muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(35):14158–14163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211314109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pessah IN, Cherednichenko G, Lein PJ. Minding the calcium store: Ryanodine receptor activation as a convergent mechanism of PCB toxicity. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;125(2):260–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wayman GA, Bose DD, Yang D, Lesiak A, Bruun D, Impey S, Ledoux V, Pessah IN, Lein PJ. PCB-95 Modulates the Calcium-Dependent Signaling Pathway Responsible for Activity-Dependent Dendritic Growth. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120(7) doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wayman GA, Yang D, Bose DD, Lesiak A, Ledoux V, Bruun D, Pessah IN, Lein PJ. PCB-95 Promotes Dendritic Growth via Ryanodine Receptor–Dependent Mechanisms. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120(7) doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zalk R, Lehnart SE, Marks AR. Modulation of the ryanodine receptor and intracellular calcium. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:367–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.053105.094237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirata H, Watanabe T, Hatakeyama J, Sprague SM, Saint-Amant L, Nagashima A, Cui WW, Zhou W, Kuwada JY. Zebrafish relatively relaxed mutants have a ryanodine receptor defect, show slow swimming and provide a model of multi-minicore disease. Development. 2007;134(15):2771–2781. doi: 10.1242/dev.004531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amiard-Triquet C. Behavioral Disturbances: The Missing Link between Sub-Organismal and Supra-Organismal Responses to Stress? Prospects Based on Aquatic Research. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 2009;15(1):87–110. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott GR, Sloman KA. The effects of environmental pollutants on complex fish behaviour: integrating behavioural and physiological indicators of toxicity. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004;68(4):369–392. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ankley GT, Bennett RS, Erickson RJ, Hoff DJ, Hornung MW, Johnson RD, Mount DR, Nichols JW, Russom CL, Schmieder PK, Serrrano JA, Tietge JE, Villeneuve DL. Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010;29(3):730–741. doi: 10.1002/etc.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connon RE, Deanovic LA, Fritsch EB, D’Abronzo LS, Werner I. Sublethal responses to ammonia exposure in the endangered delta smelt; Hypomesus transpacificus (Fam. Osmeridae) Aquat. Toxicol. 2011;105(3-4):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beggel S, Werner I, Connon RE, Geist JP. Sublethal toxicity of commercial insecticide formulations and their active ingredients to larval fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408(16):3169–3175. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ankley GT, Villeneuve DL. The fathead minnow in aquatic toxicology: Past, present and future. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006;78(1):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denslow ND, Colbourne JK, Dix D, Freedman JH, Heldbing CC, Kennedy S, Williams P. Selection of Surrogate Animal Species for Comparative Toxicogenomics. In: Benson WH, Giulio R, editors. Genomic Approaches for Cross Species Extrapolation in Toxicology. CRC PRess; Portland, OR: 2007. pp. 33–73. [Google Scholar]

- 31.USEPA . Short-term Methods for Estimating the Chronic Toxicity of Effluents and Receiving Waters to Organisms. 4 ed. Water, U. O. o., Ed; Washington DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connon RE, D’Abronzo LS, Hostetter NJ, Javidmehr A, Roby DD, Evans AF, Loge FJ, Werner I. Transcription Profiling in Environmental Diagnostics: Health Assessments in Columbia River Basin Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(11):6081–6087. doi: 10.1021/es3005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franck JPC, Morrissette J, Keen JE, Londraville RL, Beamsley M, Block BA. Cloning and characterization of fiber type-specific ryanodine receptor isoforms in skeletal muscles of fish. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 1998;275(2):C401–C415. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pessah IN, Hansen LG, Albertson TE, Garner CE, Ta TA, Do Z, Kim KH, Wong PW. Structure–Activity Relationship for Noncoplanar Polychlorinated Biphenyl Congeners toward the Ryanodine Receptor-Ca2+ Channel Complex Type 1 (RyR1) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19(1):92–101. doi: 10.1021/tx050196m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meissner G. Chapter 5 - Regulation of Ryanodine Receptor Ion Channels Through Posttranslational Modifications. In: Irina IS, editor. Curr. Top. Membr. Vol. 66. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 91–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Supavilai P, Karobath M. The interaction of [<sup>3</sup>H]PY 108-068 and of [<sup>3</sup>H]PN 200-110 with calcium channel binding sites in rat brain. J. Neural Transm. 1984;60(3):149–167. doi: 10.1007/BF01249091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pessah IN, Waterhouse AL, Casida JE. The calcium-ryanodine receptor complex of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;128(1):449–456. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. GENOME BIOLOGY. 2002;3(7) doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellinger AM, Mongillo M, Marks AR. Stressed out: the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor as a target of stress. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(2):445–453. doi: 10.1172/JCI34006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jurynec MJ, Xia R, Mackrill JJ, Gunther D, Crawford T, Flanigan KM, Abramson JJ, Howard MT, Grunwald DJ. Selenoprotein N is required for ryanodine receptor calcium release channel activity in human and zebrafish muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(34):12485–12490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806015105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pessah IN, Kim KH, Feng W. Redox sensing properties of the ryanodine receptor complex. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:A72–A79. doi: 10.2741/A741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlattner U, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Wallimann T. Mitochondrial creatine kinase in human health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2006;1762(2):164–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schredelseker J, Di Biase V, Obermair GJ, Felder ET, Flucher BE, Franzini-Armstrong C, Grabner M. The β1a subunit is essential for the assembly of dihydropyridine-receptor arrays in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(47):17219–17224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508710102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darbandi S, Franck JPC. A comparative study of ryanodine receptor (RyR) gene expression levels in a basal ray-finned fish, bichir (Polypterus ornatipinnis) and the derived euteleost zebrafish (Danio rerio) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2009;154(4):443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seebacher F, Pollard SR, James RS. How well do muscle biomechanics predict whole-animal locomotor performance? The role of Ca2+ handling. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2012;215(11):1847–1853. doi: 10.1242/jeb.067918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:23–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James RS, Walter I, Seebacher F. Variation in expression of calcium-handling proteins is associated with inter-individual differences in mechanical performance of rat (Rattus norvegicus) skeletal muscle. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2011;214(21):3542–3548. doi: 10.1242/jeb.058305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seebacher F, Walter I. Differences in locomotor performance between individuals: importance of parvalbumin, calcium handling and metabolism. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2012;215(4):663–670. doi: 10.1242/jeb.066712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiitu V, Vornanen M. Ryanodine and dihydropyridine receptor binding in ventricular cardiac muscle of fish with different temperature preferences. Journal of Comparative Physiology B: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 2003;173(4):285–291. doi: 10.1007/s00360-003-0334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fessenden JD, Feng W, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Mutational Analysis of Putative Calcium Binding Motifs within the Skeletal Ryanodine Receptor Isoform, RyR1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(51) doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calabrese EJ. Paradigm lost, paradigm found: The re-emergence of hormesis as a fundamental dose response model in the toxicological sciences. Environ. Pollut. 2005;138(3):378–411. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ekman D, Teng Q, Villeneuve D, Kahl M, Jensen K, Durhan E, Ankley G, Collette T. Profiling lipid metabolites yields unique information on sex- and time-dependent responses of fathead minnows (<i>Pimephales promelas) exposed to 17α-ethynylestradiol. Metabolomics. 2009;5(1):22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villeneuve DL, Mueller ND, Martinović D, Makynen EA, Kahl MD, Jensen KM, Durhan EJ, Cavallin JE, Bencic D, Ankley GT. Direct effects, compensation, and recovery in female fathead minnows exposed to a model aromatase inhibitor. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117(4):624–631. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heckmann LH, Sibly RM, Connon R, Hooper HL, Hutchinson TH, Maund SJ, Hill CJ, Bouetard A, Callaghan A. Systems biology meets stress ecology: linking molecular and organismal stress responses in Daphnia magna. Genome Biol. 2008;9(2):R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Versteeg DJ, Grancy RL, Giest JP. Field Utilization of Clinical Measures for Aquatic Organisms. In: Adams WJ, Chapman GA, Landis WG, editors. Aquatic Toxicology and Hazard Assessment. Vol. 10. American Society for Testing and Materials; Ann Arbor, MI: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orvos DR, Versteeg DJ, Inauen J, Capdevielle M, Rothenstein A, Cunningham V. Aquatic toxicity of triclosan. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002;21(7):1338–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simonides W, Thelen M, van der Linden CG, Muller A, van Hardeveld C. Mechanism of Thyroid-Hormone Regulated Expression of the SERCA Genes in Skeletal Muscle: Implications for Thermogenesis. Biosci. Rep. 2001;21(2):139–154. doi: 10.1023/a:1013692023449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee Y-K, Ng K-M, Chan Y-C, Lai W-H, Au K-W, Ho C-YJ, Wong L-Y, Lau C-P, Tse H-F, Siu C-W. Triiodothyronine Promotes Cardiac Differentiation and Maturation of Embryonic Stem Cells via the Classical Genomic Pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010;24(9):1728–1736. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muchekehu RW, Harvey BJ. 17β-Estradiol rapidly mobilizes intracellular calcium from ryanodine-receptor-gated stores via a PKC–PKA–Erk-dependent pathway in the human eccrine sweat gland cell line NCL-SG3. Cell Calcium. 2008;44(3):276–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Costa RR, Varanda WA, Franci CR. A calcium-induced calcium release mechanism supports luteinizing hormone-induced testosterone secretion in mouse Leydig cells. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2010;299(2):C316–C323. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00521.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sundaresan S, Weiss J, Bauer-Dantoin AC, Jameson JL. Expression of Ryanodine Receptors in the Pituitary Gland: Evidence for a Role in Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Signaling. Endocrinology. 1997;138(5):2056–2065. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adolfsson-Erici M, Pettersson M, Parkkonen J, Sturve J. Triclosan, a commonly used bactericide found in human milk and in the aquatic environment in Sweden. Chemosphere. 2002;46(9-10):1485–1489. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolpin DW, Furlong ET, Meyer MT, Thurman EM, Zaugg SD, Barber LB, Buxton HT. Pharmaceuticals, Hormones, and Other Organic Wastewater Contaminants in U.S. Streams, 1999–2000: A National Reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002;36(6):1202–1211. doi: 10.1021/es011055j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1(1):11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.