Abstract

A key challenge in developing nanoplatform-based molecular imaging is to achieve an optimal pharmacokinetic profile to allow sufficient targeting and to avoid rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). In the present study, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) were coated with a PEGylated amphiphilic triblock copolymer, making them water soluble and function-extendable. These particles were then conjugated with a near-infrared fluorescent (NIRF) dye IRDye800 and cyclic Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid (RGD) containing peptide c(RGDyK) for integrin αvβ3 targeting. In vitro binding assays confirmed the integrin-specific association between the RGD-particle adducts and U87MG glioblastoma cells. Successful tumor homing in vivo was perceived in a subcutaneous U87MG glioblastoma xenograft model by both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and NIRF imaging. Ex vivo histopathological studies also revealed low particle accumulation in the liver, which was attributed to their compact hydrodynamic size and PEGylated coating. In conclusion, we have developed a novel RGD-IONP conjugate with excellent tumor integrin targeting efficiency and specificity as well as limited RES uptake for molecular MRI.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging, Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), tumor targeting, integrin αvβ3, RGD peptide

1. Introduction

Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), with superior magnetic properties as compared to traditional gadolinium-based T1 contrast agents, hold great promise for molecular magnetic resonance imaging (mMRI) [1, 2]. A significant focus of on-going research is to replace the conventional dextran coated IONPs that rely on passive targeting with particles that have active targeting capabilities [3, 4]. Toward this end, many attempts have been made to modify the surface of IONPs to add targeting ligands, as well as to achieve better control over agent pharmacokinetics [5-7]. Although numerous reports have claimed success in delivering sufficient amounts of particles to tumor sites and inducing detectable T2 signal drop [6, 8-10], most of these studies remain at the proof-of-concept stage with insufficient control experiments and ex vivo validation. A major hurdle in this area of research is the nonspecific uptake of the nanoparticles through various body excretion mechanisms, most substantially via uptake by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) [1]. The IONPs commonly employed in these studies have an overall size of around or larger than 50 nm, a size range that facilitates phagolytic clearance. Furthermore, the IONPs are prone to forming aggregates and serum protein adsorption during the circulation, which also promote rapid RES recognition and sequestration [11]. Therefore, the size control and surface modification is of critical importance in determining the pharmacokinetic profile of the IONPs and success of in vivo targeting.

Among all the neoplastic markers that are currently under investigation, integrin αvβ3 is of particular interest [12, 13]. Integrin αvβ3 is a cell adhesion molecule that plays a vital role in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Upregulation of αvβ3 has been found to be tightly associated with a wide range of cancer types, making it a broad-spectrum tumor marker [12, 13]. We and others have previously developed a number of monomeric and multimeric arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) containing peptide probes for non-invasive imaging of αvβ3 expression [12-16] . Due to the fact that integrin αvβ3 is overexpressed on both tumor vasculature and tumor cells [13], a number of nanoparticle-RGD conjugates have been developed, for example, RGD-quantum dots (RGD-QDs) for NIRF imaging [17-19] and RGD-single walled nanotubes for Raman and photoacoustic imaging [20-22]. Most of the rigid nanoparticle conjugates bound to the integrin expressed on the tumor endothelial cells but not the integrin expressed on the tumor cells due to the ineffective extravasation of the rigid nanoparticles from the blood stream and diffusion in the interstitial space.

There have been several reports of RGD-IONP conjugates for integrin targeting [10, 23, 24]. We recently showed that, poly(aspartic acid) PASP coated IONPs can be used for tumor targeting, in which the particles were coupled with RGD for integrin targeting and macrocyclic chelator DOTA for positron emitter 64Cu labeling. The multifunctionalized IONP conjugate allow both MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [7]. However, for PASPIO, the particles were made in aqueous solution via co-precipitation method, which is suboptimal in the control of particle magnetism and T2 contrast effect [25]. These particles also had rapid and high reticuloendothelial system (RES) uptake in the liver and spleen, leading to very short circulation half-life.

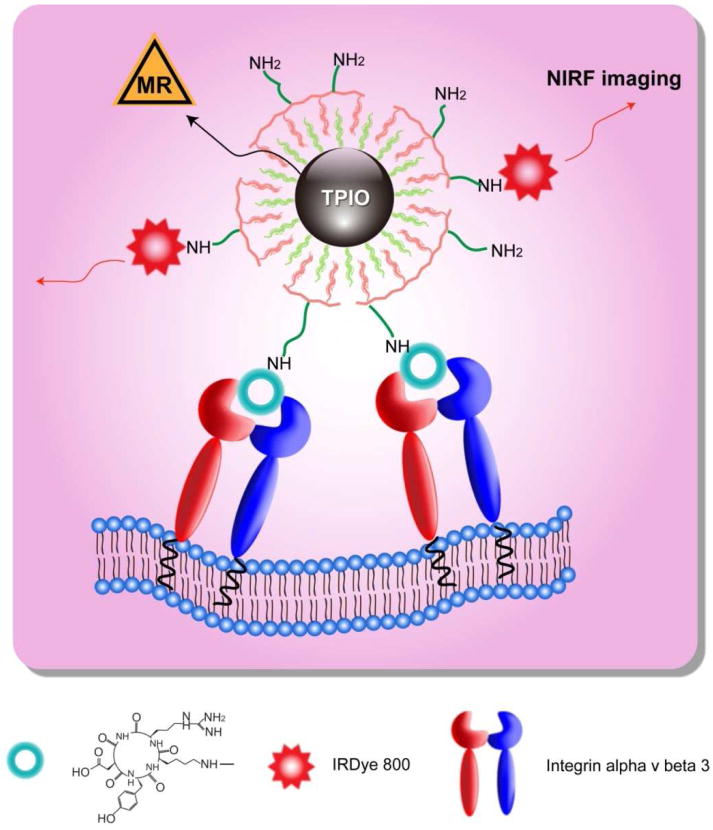

In this work, we applied a tri-block copolymer coated, IONP-RGD conjugate for tumor targeting and imaging. The IONP core was made from high temperature decomposition, which allows precise control in particle size and crystallinity. A PEGylated tri-block copolymer consisting of a polybutylacrylate segment, a polyethylacrylate segment, a polymethacrylic acid segment and a hydrophobic hydrocarbon side chain [26] was subsequently coated onto the particle surface, resulting in a bilayered coating structure, with multiple amine-terminated poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) chains exposed outside (Scheme 1). A cyclic RGD peptide, c(RGDyK), along with a NIRF dye IRDye800, were covalently coupled onto the triblock copolymer coated IONPs (TPIONPs). The pharmacokinetics and targeting specificity of the newly developed TPIONPs were evaluated both in vitro and in vivo.

Scheme 1.

Dual-modality TPIONPs for tumor integrin αvβ3 targeting.

2. Materials and Methods

IONP synthesis

All chemicals were purchased from Aldrich. IONPs with a uniform size distribution were prepared using microsized iron oxide powder as the Fe resource, oleic acid as the surfactant, and octadecene (ODE) as the solvent [27]. The iron oxide powder was dissolved in oleic acid upon heating to 200°C. The resulting iron oleate complex was utilized as the iron precursor, which underwent thermal decomposition at 320°C in ODE. The reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature, and a chloroform/acetone mixture was added to precipitate the iron oxide nanocrystals. Three cycles of centrifugation were applied to remove free surfactant. The final product was suspended in hexane or chloroform.

Surface modification and IRDye800 labeling

Surface modification and labeling of the IONPs were performed by following the previously published protocols [13, 19, 26]. In brief, IONPs and the tri-block polymer [26, 28] were mixed in chloroform at a 1:10 molar ratio for 1 h. Water was then added to the mixture at a 1:1 volume ratio, and the resulting heterogeneous mixture was subjected to rotary evaporation, which yielded a clear aqueous solution of TPIONPs. The particles were purified by high-speed centrifugation, and then resuspended in borate buffer (pH 8.5, 50 mM). IRDye800 NHS ester (Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska) in DMSO was added to the TPIONP suspension at a 20:1 dye/particle molar ratio, and the labeling was allowed to proceed for 3 h in dark. The resulting conjugates were purified with PD-10 column (GE Healthcare). Next, for RGD-coupling, 4-maleimidobutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Tokyo Chemical Industry) was added to the solution of TPIONPs at a 30:1 linker/particle molar ratio. The reaction was proceeded for 1 h in dark, and the resulting product was purified with a PD-10 column. Subsequently, RGD-SH [19] in slightly excess amount was added (∼40 aliquots), and the coupling reaction was left overnight. The free RGD-SH was removed by PD-10 column, and the final product (RGD-TPIONPs) was suspended in PBS.

Evaluating the number of amines per particle

Two hundred μL TPIONPs (∼0.1 mg Fe/ml) were subjected to dye labeling with a large excess amount of Cy5.5-NHS (GE Healthcare). The labeling procedure resembles that of IRDye800 labeling. The exact iron concentration was assessed by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis and was converted to particle concentration with the assumption that each particle was made of Fe3O4 with a 10 nm diameter and a 5.2 g/cm3 density [6]. After purification, the NIRF intensities were evaluated by fluorometric emission analysis. The results were fit into a standard curve to yield the dye concentration. According to the analysis, there are about 25-50 amines per particle. However, the actual number might be slightly higher given the potential quenching effect of multiple fluorophores in proximity [29, 30].

Cell line and animal model

The U87MG human glioblastoma cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Animal procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The U87MG tumor model was generated by subcutaneous injections of 5×106 cells in 100 μL of PBS into the front flank of female athymic nude mice (Harlan). The mice were subjected to imaging studies when the tumor volume reached 200–500 mm3 (3–4 wk after inoculation).

Prussian blue staining of TPIONP labeled U87MG cells

Approximately 1×105 U87MG cells were seeded in each cell culture chamber on the day before staining. Right before particle addition, cells were fixed with ice-cold 95% EtOH for 15 min. Afterwards, 50 nM RGD-TPIONPs or 50 nM TPIONPs in binding buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1mM MnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin; pH 7.4) were added into the culture chamber, and the incubation was performed at room temperature for 1 h with gentle shaking. The particles were then removed and the cells were washed 3x with PBS buffer. Subsequently, cells were incubated with Prussian blue staining solution (containing equal volumes 20% hydrochloric acid and 10% potassium ferrocyanide solution) for 40 min at room temperature. After Prussian blue staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS buffer and were subjected to incubation with fast red nuclear staining solution for 10 min. After consecutive dehydrations with 70%, 90% and 100% EtOH, the chamber was removed and the slide was mounted.

Competitive cell binding assay

To evaluate in vitro integrin αvβ3-binding affinity of the RGD-TPIONPs, a competitive binding assay was conducted using 125I-eschistatin (Perkin-Elmer) as the integrin αvβ3-specific radioligand on U87MG human glioblastoma cells. Experiments were performed following a previously described method [31]. The best-fit 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the U87MG cells were calculated by curve fitting using GraphPad Prism nonlinear regression software.

Phantom study

TPIONPs with various iron concentrations ranging from 2×10−4 to 5×10−6 M were suspended in 1% agarose gel in 300 μl PCR tubes. The tubes were embedded in a home-made tank, which was designed to fit the MRI coil and was filled with 1% agarose gel. T2-weighted MRI images were acquired on a GE 7.0 T small animal MRI system with the following parameters: TR 3000 ms; TE 8, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140 ms; flip angle 30°; FOV 6×6, 256×256 matrix; slice thickness 1mm.

In vivo MR imaging

Tumor-bearing mice were anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane (IsoFlo; Abbott Laboratories) in 1:2 O2:N2. Afterwards, RGD-TPIONPs and TPIONPs were injected through the tail vein (10 mg Fe/kg per mouse). T2-weighted fast spin-echo images were acquired on a 7.0 T small animal MRI system, before and 4 h after particle injection, with the following parameters: TE 40 ms, TR 3000, thickness 1 mm, FOV 6×6, NEX 1.0, Echo 1/1.

In vivo and ex vivo NIRF imaging

IRDye800 labeled RGD-TPIONPs and TPIONPs were injected through tail vein (0.5 nmol IRDye800 per mouse) after anesthetizing the mice with isoflurane. The imaging was performed on a Pearl optical imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska) using the IRDye800 filter set. At the end of in vivo imaging, mice were sacrificed and the major organs were harvested for ex vivo imaging.

Histological study

Prussian blue staining of major organs

Major organs of the mice were kept in optimal-cutting-temperature (O.C.T.) compound and stored in freezer at -80°C. Later on, the tissue samples were cut into 10 μm thick slices. For Prussian blue staining, the tissue slides were first warmed for 20 min at room temperature and then fixed with ice-cold acetone for 5 min. After fixation, slides were dried at room temperature for 20 min and then immersed in staining solution (20% hydrochloric acid and 10% potassium ferrocyanide solution mixture, 1:1 volume ratio) for 40 min, and counterstained with eosin for 5 min. Afterwards, the slides were dehydrated consecutively with 90%, 95% and 100% EtOH (3 min each), cleared with xylene, and mounted with Permount medium.

Double staining of Prussian blue and CD31, murine β3 and F4/80

Frozen U87MG tumor tissues were sectioned into 10 μm thick slices. Slides were warmed for 20 min at room temperature after removal from -80°C freezer and were then fixed with ice-cold acetone for 5 min. After fixation, slides were incubated with 0.3% H2O2 solution in PBS for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Then slides were rinsed 3 times with PBS (2 min each). Rat anti-mouse CD31 primary antibody diluent (1:50) was subsequently applied to the tissue sections, and the incubation was left at room temperature for 1 h in a humid chamber. After rinsing with PBS (3×2 min), a biotinylated anti-rat IgG secondary antibody solution (1:50) was applied, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were rinsed again with PBS and incubated with streptavidin-HRP solution for 30 min at room temperature. After another washing cycle, the slides were developed with DAB substrate solution until the desired color intensity was reached. The resulting slides were subjected to Prussian blue staining with the procedure described above. Double staining with Prussian blue and murine integrin β3 (or F4/80) was conducted using the same protocol with the exception of the primary antibodies used. For F4/80 staining, rat anti-mouse F4/80 mAb was used and for murine β3 staining, hamster anti-mouse β3 mAb and biotinylated anti-hamster IgG secondary antibody solution were used.

3. Results

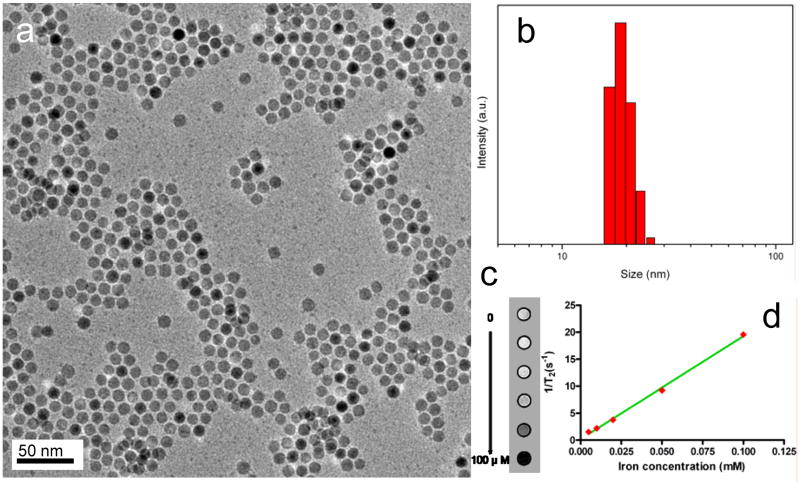

The IONPs were synthesized by a pyrolysis-based protocol modified from previous publications [27, 32]. The as-synthesized spherical, highly-ordered Fe3O4 crystals, with a diameter of around 10 nm (Fig. 1a) are hydrophobic owing to an oleate coating. The subsequently added polymer, being amphiphilic, interacted with the original coating, forming a dilayered structure and rendered the particles water soluble. Such TPIONPs can be dispersed in water and various buffer solutions for months without precipitation, suggesting a good in vitro stability. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis revealed that such TPIONPs have a hydrodynamic size of ∼20 nm in aqueous solution, which is close to the assumption of a 10 nm core plus a 5 nm coating (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) TEM of the 10 nm IONPs. (b) Dynamic light scattering analysis of the TPIONPs. The mean diameter is 19.3 nm. (c) T2-weighted phantom images of TPIONPs at elevated iron concentrations. (d) 1/T2 vs. Fe concentration curve of TPIONPs. The r2 relaxivity was evaluated to be 190 mM-1s-1.

To evaluate the MRI contrast effect of these particles, a phantom study was performed with TPIONPs of elevated concentrations. As shown in Fig. 1c, the TPIONPs displayed a clear concentration-dependent T2 signal reduction effect, with an r2 value of 190 mM-1s-1 (Fig. 1d), which was much higher than that of Feridex (123.6 mM-1s-1) under the same condition. This is likely attributed to a better magnetization control offered by the pyrolysis-based synthetic routes [9, 33].

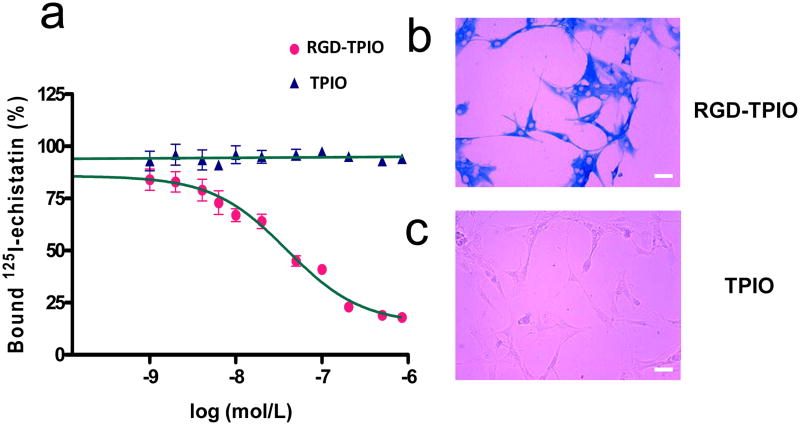

An organic dye, IRDye800, was employed to optically label the TPIONPs. IRDye800 has excitation and emission wavelengths in the near-infrared region (maximum excitation and emission at 774 and 789 nm in PBS, respectively), therefore possesses improved tissue penetration as compared to conventional fluorophores in the visible range. Approximately 10 IRDye800 molecules were coupled onto each nanoparticle, as evaluated by the fluorometric emission and ICP analyses. Meanwhile, c(RGDy(ε-acetylthiol)K) (RGD-SH) [19], as the targeting agent, was also covalently coupled to the TPIONPs. With an estimated coupling efficiency of ∼50% [19], there are about 15 RGD peptides on each TPIONP surface. The affinity of such RGD coupled TPIONPs (RGD-TPIONPs) toward αvβ3 integrin was assessed by receptor binding assay with integrin-positive U87MG human glioblastoma cells using 125I-echistatin as the competitive radioligand. As shown in Fig. 2a, the RGD-TPIONPs can replace 125I-echistatin in a concentration-dependent manner, and the IC50 value was evaluated to be 39.2 nM, as compared to that of 250 nM for monomeric RGD peptide c(RGDyK) [34]. Such affinity enhancement is likely due to the polyvalency effect of multiple RGD peptides anchored onto each TPIONP, as was observed elsewhere for other RGD-nanoparticle conjugates [35, 36]. The RGD-mediated cell targeting was further confirmed in an in vitro Prussian blue staining study performed on U87MG cells treated with either RGD-TPIONPs or TPIONPs. Incubation of U87MG cells with RGD-TPIONPs (50 nM) led to massive positive staining (Fig. 2b) whilst the cells incubated with the same amount of TPIONPs resulted in almost no particle accumulation (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

(a) Binding affinity assay with RGD-TPIONPs and TPIONPs on U87MG glioblastoma cells using 125I-echistatin as the radioligand. The best fit IC50 value is 39.2 nM; (b) Prussian blue staining with RGD-TPIONPs on U87MG cells; (c) Prussian blue staining with TPIONPs on U87MG cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

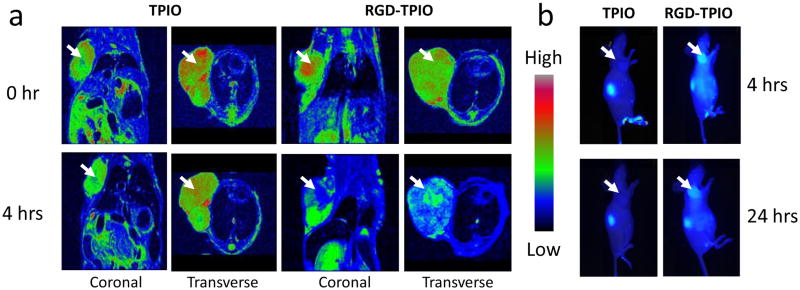

Encouraged by the phantom study and the affinity assessment, we then moved to the in vivo evaluation. The animal tumor model was established on athymic nude mice by inoculating 5×106 U87MG cells at the right front flank. The mice were subjected to MR imaging studies at 3-4 weeks after tumor inoculation when the tumor reached a size of 200–500 mm3. The MRI study was performed on a 7.0 T small animal MRI system. Both RGD-TPIONPs and TPIONPs were intravenously administrated at a dose of 10 mg Fe/kg, and T2-weighted fast spin-echo images pre- and 4 h post injection, were acquired. As displayed in Fig. 3a, a dramatic signal drop was witnessed at the tumor area (indicated by white arrows) after the injection of RGD-TPIONPs while only marginal signal drop was observed in mice injected with TPIONPs. This is consistent with the NIRF imaging results (Fig. 3b), which found impressive tumor/muscle contrast in the RGD-TPIONP group but not in the TPIONP group. It is of note that even at the 24 h time point, clear tumor contrast as well as nontrivial normal tissue background were observed in the optical images, suggesting a long circulation half-life of the newly developed TPIONP conjugates.

Figure 3.

(a) MR imaging of U87MG tumor-bearing mice injected with RGD-TPIONPs or TPIONPs. The images were taken both coronally and transversly before and 4 h after particle injection. TPIONPs induced marginal signal decrease; on the contrary, RGD-TPIONPs could selectively home to the tumor site and cause severe T2 reduction. (b) Optical imaging of U87MG tumor-bearing mice injected with RGD-TPIONPs or TPIONPs. The images were acquired 4 h and 24 h post injection. RGD-TPIONPs injected mice showed good contrast at tumor sites at both time points.

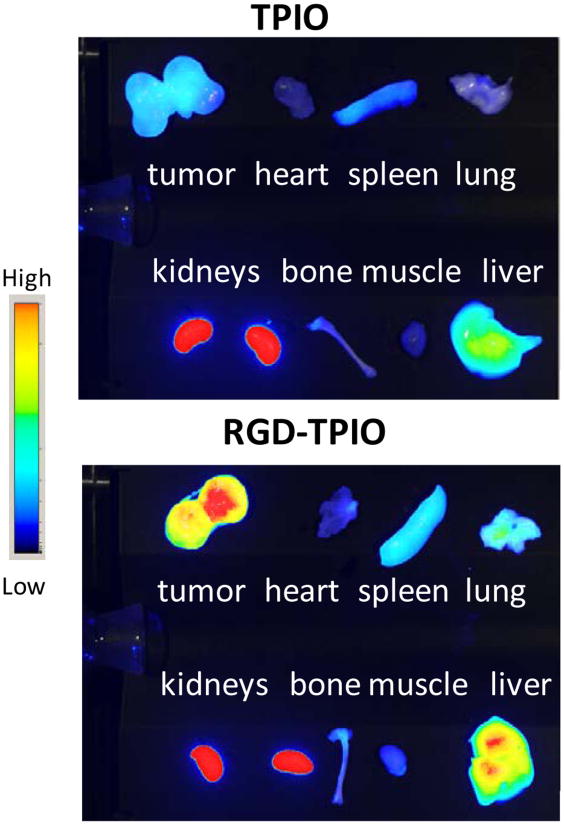

The biodistribution of IONPs was evaluated in an ex vivo NIRF study with the dissected major organs and the allograft tumors (Fig. 4). Clear difference in tumor uptake was observed between the RGD-TPIONP group and the TPIONP group. The accumulation in other tissues and organs was comparable for RGD-TPIONP and TPIONP. It indicates that aside from increased tumor homing, the incorporation of RGD peptide did not significantly affect the particle pharmacokinetics. For both types of particles, considerable intensities in the liver and spleen were observed, which was attributed to typical RES-mediated uptake. Notably, prominent optical intensities from kidneys were observed, indicating apparent dissociation of the triblock copolymer coating from the iron oxide core. The IRDye800 labeled RGD-polymer conjugate can be cleared via the renal route as well as binding to integrins expressed on the renal endothelium and tubular epithelium [37].

Figure 4.

Ex vivo NIRF imaging on major organs harvested from TPIONP and RGD-TPIONP injected mice. Clear tumor contrast was observed in RGD-TPIONP injected mice. Uptake was also found in the liver, spleen and kidneys to various extents.

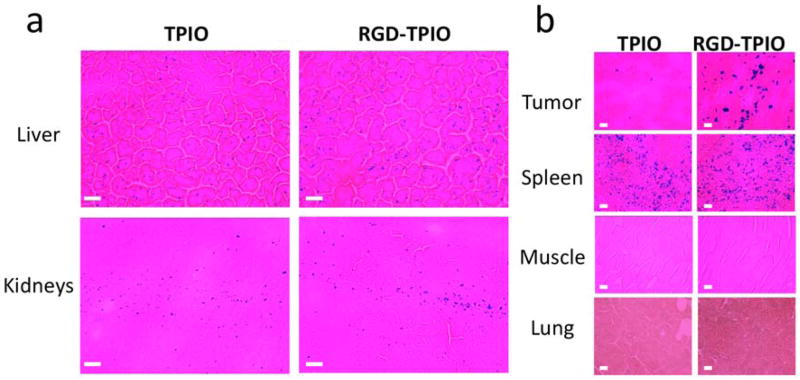

To better understand the particle pharmacokinetics, Prussian blue staining was performed on tumor and major organs dissections. While NIRF intensities are indicative of the polymer coating whereabouts, Prussian blue staining is a true reflection of IONP distribution. Sporadic blue spots were found in the kidneys, suggesting no obvious renal clearance of the rigid inorganic nanoparticles. Similar with many other IONP preparations, both RGD-TPIONPs and TPIONPs has prominent spleen uptake (Fig. 5). It is striking that the liver uptake of RGD-TPIONPs and TPIONPs was rather low and no agglomerations of positive staining was observed, indicating a high stability of the particles in the circulation, which was rarely observed before [6, 7, 38]. Although the detailed mechanism is unknown at this stage, we believe it is closely related to the compact particle size and the appropriate polymer coating strategy. Particles smaller than 30 nm are believed to be less provocative in inducing RES uptake than the larger ones, as was manifested by Combidex for possessing a longer circulation half life and largely different pharmacokinetics with respect to their bulkier analog, Feridex [4, 39]. Meanwhile, the PEGylation may also play a part. The presence of PEG on the surface may inhibit serum protein adsorption, which lead to a less extent of opsonization, RES reorganization and elimination [1].

Figure 5.

Prussian blue staining of tumor and major organs. (a) Low and sparse blue spots were found throughout the liver and kidney tissues for both TPIONP and RGD-TPIONP injected mice. (b) Significant difference in tumor homing was found between the positive group and the control group. Typical spleen uptake was found in both groups. Meanwhile, no uptake was found in the muscle or lung. Scale bar, 10 μm.

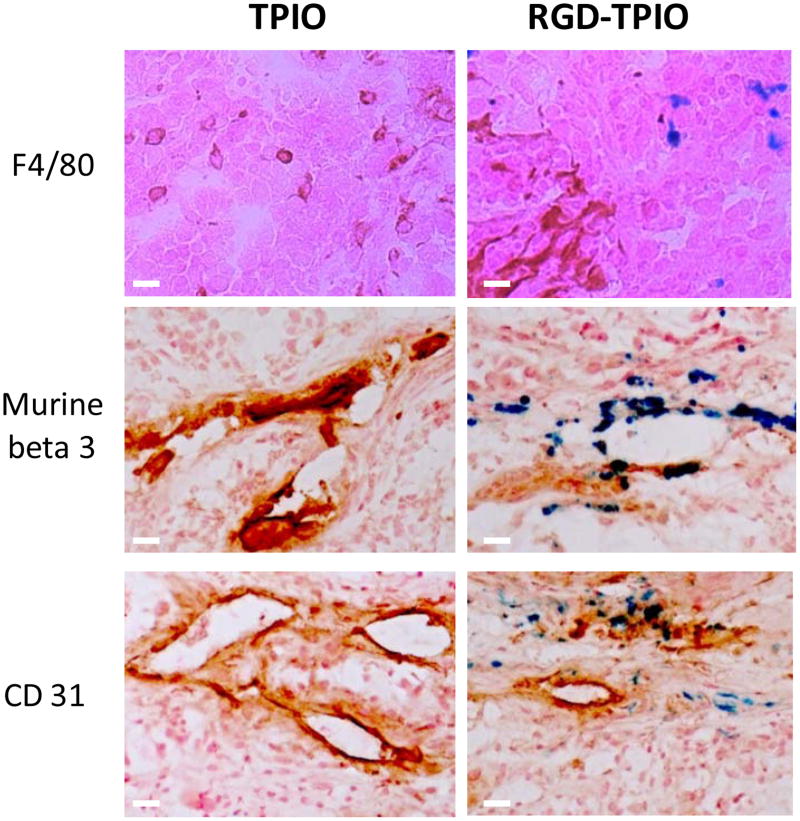

To validate the targeting specificity, the mice were sacrificed after the 4 h postinjection scan and the tumors were sectioned and subjected to histological studies (Fig. 6). Little superposition of nanoparticles (blue) and murine F4/80 positive cells (red) staining was found, suggesting that the particle tumor accumulation was not caused by macrophage uptake. Meanwhile, the perfect overlap of IONPs (blue) and murine β3 (red) positive staining (Fig. 6) indicates that the particle homing is indeed specifically mediated by RGD-integrin interaction. Additionally, in Prussian blue and murine CD31 double staining (Fig. 6), it was found that although many particles were attached to the interior blood vessel surface, some of them were managed to extravasate. Associated with the β3 staining result, we may conclude that although RGD-mediated neoplastic vessel binding takes place in the tumor accumulation, direct tumor cell binding also occurs but to a much less degree. It is worth pointing out that, with a repetitive washing process, fewer particles were found in the double staining study than in the single staining study.

Figure 6.

Prussian blue and CD31/murine β3/F4/80 double staining on the tumor sections. F4/80 and Prussian double staining indicated that particle enrichment at the tumor area was not caused by macrophage uptake; β3 and Prussian blue double staining showed a good overlap, suggesting that the particle accumulation was indeed governed by RGD-αvβ3 interaction; and CD31 and Prussian blue double staining demonstrated that, while most of the particles resided at the interior side of the blood vessels, many of them managed to extravasate and bound to tumor cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

4. Discussion

In this study, a triblock copolymer, made of polybutylacrylate, polyethylacrylate, polymethacrylic acid and octylamine, was utilized to coat onto oleate coated IONPs and render the particles water soluble. Compared with many other surface modification methods, especially those via ligand exchange, such phase transfer is straightforward, with high throughput and high yield [5, 40, 41]. The polymer coating provides the IONPs with good protection, which is evidenced by both in vitro and in vivo observations. Clear tumor contrast was found in MRI and NIRF imaging with RGD-TPIONPs, indicating a successful RGD-integrin governed tumor targeting. On the other hand, owing to the compact size and the PEGylated triblock copolymer coating, a remarkably low hepatic uptake was witnessed, which is rarely reported for IONPs with other types of coatings. Given its previous success in quantum dot modification [26], this copolymer coating might be generalized for functionalization of other nanoparticles.

Optical imaging with dyes coupled to the triblock copolymer showed some detachment of the polymer from the particles, which resulted in a false positive renal accumulation in NIRF imaging study and might have contributed to the readouts in tumor and other major organs. So it should be kept in mind that the NIRF intensities, although showed certain correlation with the histological and MRI data, are not identical to the particle whereabouts. To further optimize this system, one critical point that needs to be addressed is the improvement of the stability of the dilayered structure, which might be achieved by fine-tuning the length of the hydrophobic side chain of the triblock copolymer. Another variable that is worth exploring is the length of PEG chain. Alternating PEG chain may affect the hydrodynamic size, hydrophilicity as well as the anti-opsonization nature [1, 5, 42], hence may impact the pharmacokinetics of the particles as well.

We choose cyclic RGD peptide as the biovector not only for its availability and chemical rigidity, but also for three other particular features that favor its role in the context of nanoparticle based imaging. First of all, its compact size. Being a pentameric amino acid sequence motif, the impartation of RGD onto the nanoparticles causes minimal size expansion, therefore little impact on the in vivo biodistribution. As manifested by the NIRF result in this study, there are no apparent alternations in pharmacokinetics for RGD-TPIONP and TPIONP, except for the increased tumor homing. Meanwhile, the compact size also allows a maximum number of RGD conjugation on each particle with little steric hindrance. In the case of RGD-TPIONPs, a binding affinity of 39.2 nM was observed, compared to that of 250 nm for RGD monomer. Second, the integrin receptor is expressed on both tumor vasculature and tumro cells. So RGD conjugate can be designed for specific tumor targeting without the need of extravasation and diffusion in the tumor interstitial space. In this study, the particles were found to be mostly accumulated on the tumor vasculature and to a much less extent on U87MG tumor cells. Finally, αvβ3 integrin is found to be overexpressed on neoplastic endothelial cells of most solid tumors, the success of RGD-TPIONP for U87MG tumor targeting will be applicable to other vascularised solid tumors.

5. Conclusions

A tri-block copolymer was utilized to coat IONPs, resulting in physiologically stable TPIONPs. Such particles were coupled with IRDye800 and RGD peptide, and their pharmacokinetics was carefully evaluated on a U87MG xenografted tumor model. The nanoconjugates showed excellent tumor targeting efficiency, relatively long circulation half-life and limited liver macrophage engulfment, which was attributed to the stability and anti-opsonization capacity afforded by the polymer coating.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Xie J, Huang J, Li X, Sun S, Chen X. Iron oxide nanoparticle platform for biomedical applications. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:1278–1294. doi: 10.2174/092986709787846604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai W, Chen X. Nanoplatforms for targeted molecular imaging in living subjects. Small. 2007;3:1840–1854. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corot C, Robert P, Idee JM, Port M. Recent advances in iron oxide nanocrystal technology for medical imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1471–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie J, Xu C, Kohler N, Hou Y, Sun S. Controlled PEGylation of monodisperse Fe3O4 nanoparticles for reduced non-specific uptake by macrophage cells. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3648–3652. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie J, Chen K, Lee HY, Xu C, Hsu AR, Peng S, et al. Ultrasmall c(RGDyK)-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles and their specific targeting to integrin αvβ3-rich tumor cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7542–7543. doi: 10.1021/ja802003h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HY, Li Z, Chen K, Hsu AR, Xu C, Xie J, et al. PET/MRI dual-modality tumor imaging using arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD)-conjugated radiolabeled iron oxide nanoparticles. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1371–1379. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montet X, Montet-Abou K, Reynolds F, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Nanoparticle imaging of integrins on tumor cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8:214–222. doi: 10.1593/neo.05769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Huh YM, Jun YW, Seo JW, Jang JT, Song HT, et al. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nat Med. 2007;13:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Jugold M, Woenne EC, Lammers T, Morgenstern B, Mueller MM, et al. Specific targeting of tumor angiogenesis by RGD-conjugated ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles using a clinical 1.5-T magnetic resonance scanner. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1555–1562. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory to practice. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:283–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai W, Chen X. Multimodality molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(2):113S–128S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Imaging of integrins as biomarkers for tumor angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2943–2973. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beer AJ, Schwaiger M. Imaging of integrin alphavbeta3 expression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008 Dec;27:631–644. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X. Multimodality imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3expression. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006 Feb;6(2):227–234. doi: 10.2174/138955706775475975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dijkgraaf I, Beer AJ, Wester HJ. Application of RGD-containing peptides as imaging probes for αvβ3 expression. Front Biosci. 2009;14:887–899. doi: 10.2741/3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai W, Chen X. Preparation of peptide-conjugated quantum dots for tumor vasculature-targeted imaging. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:89–96. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai W, Chen K, Li ZB, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Dual-function probe for PET and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of tumor vasculature. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1862–1870. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai W, Shin DW, Chen K, Gheysens O, Cao Q, Wang SX, et al. Peptide-labeled near-infrared quantum dots for imaging tumor vasculature in living subjects. Nano Lett. 2006;6:669–676. doi: 10.1021/nl052405t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De la Zerda A, Zavaleta C, Keren S, Vaithilingam S, Bodapati S, Liu Z, et al. Carbon nanotubes as photoacoustic molecular imaging agents in living mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Cai W, He L, Nakayama N, Chen K, Sun X, et al. In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zavaleta C, de la Zerda A, Liu Z, Keren S, Cheng Z, Schipper M, et al. Noninvasive Raman spectroscopy in living mice for evaluation of tumor targeting with carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2800–2805. doi: 10.1021/nl801362a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montet X, Funovics M, Montet-Abou K, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Multivalent effects of RGD peptides obtained by nanoparticle display. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6087–6093. doi: 10.1021/jm060515m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montet X, Montet-Abou K, Reynolds F, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Nanoparticle imaging of integrins on tumor cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8:214–222. doi: 10.1593/neo.05769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Huh YM, Jun Y, Seo J, Jang J, Song HT, et al. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nature Medicine. 2007;13:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu WW, Falkner JC, Yavuz CT, Colvin VL. Synthesis of monodisperse iron oxide nanocrystals by thermal decomposition of iron carboxylate salts. Chem Commun (Camb) 2004:2306–2307. doi: 10.1039/b409601k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao X, Chung LW, Nie S. Quantum dots for in vivo molecular and cellular imaging. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;374:135–145. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-369-2:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Josephson L, Kircher MF, Mahmood U, Tang Y, Weissleder R. Near-infrared fluorescent nanoparticles as combined MR/optical imaging probes. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 200;13:554–560. doi: 10.1021/bc015555d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kircher MF, Weissleder R, Josephson L. A dual fluorochrome probe for imaging proteases. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2004;15:242–248. doi: 10.1021/bc034151d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, Zhang X, Xiong Z, Cheng Z, Fisher DR, Liu S, et al. microPET imaging of glioma integrin αvβ3 expression using (64)Cu-labeled tetrameric RGD peptide. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1707–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J, An K, Hwang Y, Park JG, Noh HJ, Kim JY, et al. Ultra-large-scale syntheses of monodisperse nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2004;3:891–895. doi: 10.1038/nmat1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jun YW, Seo JW, Cheon J. Nanoscaling laws of magnetic nanoparticles and their applicabilities in biomedical sciences. Accounts of chemical research. 2008;41:179–189. doi: 10.1021/ar700121f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F, Tan G, Li J, Dong X, Krissansen GW, Sun X. Gene transfer of endostatin enhances the efficacy of doxorubicin to suppress human hepatocellular carcinomas in mice. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1381–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montet X, Funovics M, Montet-Abou K, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Multivalent effects of RGD peptides obtained by nanoparticle display. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6087–6093. doi: 10.1021/jm060515m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang W, Kim BY, Rutka JT, Chan WC. Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li ZB, Cai W, Cao Q, Chen K, Wu Z, He L, et al. 64Cu-labeled tetrameric and octameric RGD peptides for small-animal PET of tumor αvβ3 integrin expression. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1162–1171. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee HY, Lee SH, Xu CJ, Xie J, Lee JH, Wu B, et al. Synthesis and characterization of PVP-coated large core iron oxide nanoparticles as an MRI contrast agent. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:165101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/16/165101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corot C, Robert P, Idee JM, Port M. Recent advances in iron oxide nanocrystal technology for medical imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1471–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie J, Xu C, Xu Z, Hou Y, Young KL, Wang S, et al. Linking Hydrophilic Macromolecules to Monodisperse Magnetite (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles via Trichloro-s-triazine. Chem Mater. 2006;18:5401–5403. doi: 10.1021/cm061793c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jun YW, Huh YM, Choi JS, Lee JH, Song HT, Kim S, et al. Nanoscale size effect of magnetic nanocrystals and their utilization for cancer diagnosis via magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5732–5733. doi: 10.1021/ja0422155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:214–221. doi: 10.1038/nrd1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]