Abstract

Goals

To determine whether patients with celiac disease and low vitamin D levels also have a higher prevalence of other autoimmune diseases (AD) as compared to patients with normal vitamin D levels.

Background

Patients with CD carry a higher risk of other autoimmune disorders. Because of its immunoregulatory properties, vitamin D deficiency has been proposed in the pathogenesis of a variety of AD. Whether low vitamin D levels in patients with CD can predict concomitant AD is unknown.

Study

A retrospective cross-sectional study of 530 adult patients with CD and a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level on record at CUMC.

Results

133 patients (25%) had vitamin D deficiency. The prevalence of AD was similar among those with normal vitamin D (11%), insufficiency (9%), and deficiency (12%, p=0.66). On multivariate analysis, adjusting for age of CD diagnosis and gender, vitamin D deficiency was not associated with AD (OR 1.35 95% CI 0.62–2.95). The risk of psoriasis was higher in patients with vitamin D deficiency (7% vs. 3%, p=0.04). Vitamin D deficiency was more common in those who presented with anemia (39%) than in those who did not (23% p=0.002).

Conclusion

Vitamin D deficiency in CD is common but does not predict AD. Psoriasis is increased in vitamin D deficient CD patients. Assessment of vitamin D appears to be a high-yield practice, especially in those CD patients who present with anemia.

Introduction

Celiac Disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder induced by the ingestion of gluten in genetically predisposed individuals who carry the HLA-DQ2 or DQ-8 alleles.1 CD commonly affects the gastrointestinal tract, classically causing diarrhea and malabsorption; in addition, it has multiple extra-intestinal manifestations, including iron-deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, and dermatitis herpetiformis.2

Recent studies have shown that autoimmune diseases tend to occur three to ten times more frequently in patients with CD than in the general population.3–4 Autoimmune disorders commonly associated with CD include autoimmune thyroid disease, Type 1 diabetes mellitus, Sjogren’s syndrome, Addison’s disease, autoimmune hepatitis, psoriasis and primary biliary cirrhosis.4–10 Several hypotheses have been made regarding this increased incidence of autoimmune diseases in patients with CD. For example, a longer duration of gluten exposure has been considered to be a risk factor for the development of associated autoimmune disorders in CD patients11–12, but not all studies have confirmed this hypothesis.4 Also, the presence of DQ2/DQ8 alleles in patients with CD has been thought to act as a susceptibility gene for other autoimmune disorders. However, only type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroid disorders, and Addison’s disease share this common allele. An immunological mechanism has yet to be elucidated to explain the increased prevalence of other autoimmune disorders seen in CD patients.13

Vitamin D plays a diverse role in human physiology. While it is well known that vitamin D homeostasis is important in maintaining bone mineralization and preventing osteoporosis, recent research has also implicated its role in a number of disease processes including cancer and cardiovascular disease.14 Several observational studies have suggested that Vitamin D insufficiency plays a role in the development of cancers of the colon, breast, and prostate, as well as lymphoma.15–19 In addition, experimental data has shown that vitamin D deficiency may be linked with hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke.14

Vitamin D has multiple immunoregulatory properties and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders.20 Vitamin D is known to interact with the immune system by suppressing several autoimmune pathways including inhibiting antibody secretion and autoantibody production from B cells, Th-17 cells, dendritic cell differentiation and co-stimulatory molecule secretion such as IL-12.18, 20–24 Additionally, polymorphisms in the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) have been shown to increase susceptibility to certain autoimmune disorders, such as type 1 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease.25–26 Furthermore, Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency have been linked to a number of autoimmune disorders, including Crohn’s disease27, multiple sclerosis28–31, rheumatoid arthritis32–33, vitiligo34, and psoriasis.17

Vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency (commonly defined as levels below 20 and 20–30 mg/dL, respectively) has been estimated to affect upwards of 80% of the general US population and has been shown to be prevalent across all age groups, both genders, and multiple geographic locations.18, 35–36 Common causes of vitamin D deficiency include reduced skin synthesis from skin pigmentation, increased catabolism from medications such as anti-convulsants and antiretroviral therapy, nutritional deficiencies and malabsorptive disorders including CD.37 There have been no studies investigating whether low vitamin D levels in CD patients predict the presence of concomitant autoimmune disease.38–39 Considering the increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases seen in patients with CD and the role that vitamin D plays in regulating the immune system, we aimed to determine whether patients with CD and low vitamin D levels have a higher prevalence of other autoimmune diseases as compared to patients with CD and normal vitamin D levels.

Materials and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of CD patients who had previously provided consent to be included in a prospectively maintained database starting in January 1999 at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University. Information compiled from the database and used in our study included gender, date of birth, date of CD diagnosis, initial symptoms prompting their diagnosis of CD, and any previously or concurrently diagnosed medical conditions.

Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D were obtained from the Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) electronic medical record system. Patients were only included in the study if they were over the age of 18 at the time of inclusion in the database and had at least one 25-hydroxyvitamin D level on record. For each patient, the lowest vitamin D level on record was included. A total of 530 patients with both CD and at least one 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in the CUMC system were identified and included in our study.

We compared those patients with a normal vitamin D level (≥30 mg/dL), to those with vitamin D insufficiency (20–29 mg/dL) and vitamin D deficiency (<20 mg/dL) with regards to prevalence of autoimmune disorders. Autoimmune disorders included in the study included Addison’s disease, autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune neutropenia, Graves Disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and vitiligo.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of interest was the presence of concomitant autoimmune disease. We compared the prevalence of autoimmune disease in those patients with normal vitamin D levels to those with vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency. We also assessed gender, age at vitamin D testing, and age of CD diagnosis for association with autoimmune disease. We used the Pearson chi-square and Fisher exact tests to compare proportions, and the student t test to compare continuous variables. We then performed multiple logistic regression to assess for an association between vitamin D status and autoimmune disease, after controlling for age of CD diagnosis and gender.

All p values reported are 2-sided. We used SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC) for all analyses. This Institional Review Board at Columbia University Medical Center approved the creation and maintenance of this database.

Results

A total of 530 patients were identified who had both CD and a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level on record (Table 1). The study cohort included 70% females with a mean age at the time of CD diagnosis of 44 years and the mean age at the time of vitamin D check of 54 years. Among the 530 patients, 133 (25%) were vitamin D deficient, 180 (34%) were vitamin D insufficient, and 217 (41%) had normal vitamin D levels. Vitamin D deficiency was similarly present among males and females (28% vs. 24%, p= 0.31) and among all age groups at the time that vitamin D levels were obtained (p=0.8).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with celiac disease with a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level on record (n=530)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender (N/%) | |

| Male | 157 (29.6) |

| Female | 373 (70.4) |

|

| |

| Age at Vitamin D check | |

| Mean | 53.47 |

| Median | 53 |

| Range | 73 |

|

| |

| Age of CD Diagnosis | |

| Mean | 44.09 |

| Median | 43 |

| Range | 80 |

|

| |

| Vitamin D | |

| Mean | 29 |

| Median | 26 |

| Range | 84 |

|

| |

| Vitamin D Status | |

| Deficient (<20) | 133 (25.1) |

| Insufficient (20≤x<30) | 180 (34.0) |

| Normal (≥30) | 217 (40.9) |

|

| |

| Autoimmune Disease (N/%) | |

| Yes | 55 (10) |

| No | 475 (90) |

Of the 530 patients in the cohort, 55 patients (10%) had an autoimmune disorder. The prevalence of autoimmune disorders was similar among those with normal vitamin D (11%), vitamin D insufficiency (9%), and vitamin D deficiency (12%, p=0.66, Table 2). Among those patients with more than one autoimmune disorder (n=5), 2 patients (40%) had a vitamin D level less than 20 mg/dL, similar to the proportion of those with one autoimmune disorder (29%) or no additional autoimmune disorder apart from CD (25%, p=0.6). In addition, the mean vitamin D level was similar among patients with an autoimmune disorder (29.5 mg/dL) and those without an autoimmune disorder (29.0 mg/dL).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for association with autoimmune disease

| Category | N/% With Additional Autoimmune Disease | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 15 (9.6) | 0.6868 |

| Female | 40 (10.7) | |

|

| ||

| Age Quartile at vitamin D check | ||

| Q1 (18–40) | 8 (5.8) | 0.0421 |

| Q2 (40–53) | 16 (12.7) | |

| Q3 (53–68) | 21 (15.2) | |

| Q4 (68–91) | 10 (7.8) | |

|

| ||

| Age of CD Diagnosis | ||

| 1–30 | 6 (6.2) | 0.0312 |

| 31–43 | 13 (11.0) | |

| 44–58 | 18 (16.4) | |

| 59–81 | 9 (7.6) | |

|

| ||

| Vitamin D status | ||

| Deficient(<20) | 16 (12.0) | 0.6601 |

| 20≤x<30 | 16 (8.9) | |

| ≥30 | 23 (10.6) | |

On multivariate analysis (Table 3), when adjusting for age of CD diagnosis and gender, vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency was not associated with autoimmune disorders (OR for deficiency 1.35 95% CI 0.62–2.95; OR for insufficiency 1.10 95% CI 0.52–2.29). Gender was also not associated with autoimmune disorders (OR 0.98 95% CI 0.49–1.96). Increasing age of CD diagnosis appeared to be associated with autoimmune disease, though this was not noted in the oldest age quartile.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of predictors of autoimmune disease

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D status | |||

| Deficient (<20) | 1.35 | 0.618–2.945 | |

| 20≤x<30 | 1.10 | 0.524–2.289 | |

| ≥30 | 1.00 | [ref] | 0.7473 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0.98 | 0.492–1.962 | |

| Female | 1.00 | [ref] | 0.9600 |

| Age of Diagnosis | |||

| 1–30 | 1.00 | [ref] | 0.0442 |

| 31–43 | 2.34 | 0.854–6.416 | |

| 44–58 | 3.54 | 1.346–9.299 | |

| 59–81 | 1.52 | 0.521–4.436 | |

Mode of Presentation and Degree of Villous Atrophy

Vitamin D deficiency (<20 mg/dL) was more common in patients who presented with anemia (39%) than in those patients who did not present with anemia (23%, p=0.002). Similarly, vitamin D deficiency was less common in patients who presented incidentally on endoscopy (4%) than in those patients who did not present with this mode of presentation (26%, p=0.01). No other modes of presentation were more or less likely to be associated with vitamin D deficiency (table 4).

Table 4.

Mode of CD presentation

| Presentation | Vitamin D <20 | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal Pain | 13/42(30.95) | 0.3578 |

| Anemia | 32/82(39.02) | 0.0016 |

| Bone Disease | 11/29(37.93) | 0.1218 |

| Diarrhea/Malabsorption | 49/193 (25.39) | 0.9059 |

| Incidental on Endoscopy | 1/23 (4.35) | 0.0141 |

| Screening | 9/31(29.03) | 0.6693 |

| Weight Loss | 5/26 (19.23) | 0.6437 |

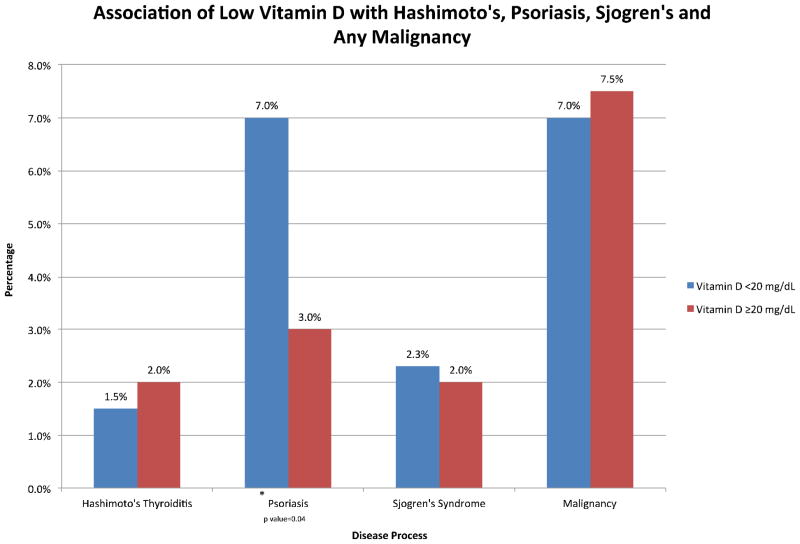

The most common autoimmune diseases seen in our population of CD patients included psoriasis (n=19), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (n=10), and Sjogren’s syndrome (n=10). In addition, several malignancies were noted in our original cohort, including breast, melanoma, colon, prostate, and thyroid cancer. When vitamin D levels were compared among these specific diseases, psoriasis was more common among those with vitamin D deficiency than those with vitamin D levels greater than 20 mg/dL (7% vs. 3%, p= 0.04). However, the prevalence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and noted malignancies were similar in those patients with vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D levels greater than 20 mg/dL (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Association of Low Vitamin D with Hashimoto’s, Psoriasis, Sjogren’s and Any Malignancy

The degree of villous atrophy was recorded in 191 patients, 36% of the cohort. Of these 191 patients, 80 (42%) had Marsh 3C lesions, or total villous atrophy, while the remaining 111 patients had lesser degrees of villous atrophy. Among the 80 patients with total villous atrophy on diagnosis, 16 (20%) had a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level <20, as compared to 30 of the 111 (27%) patients with lesser degrees of villous atrophy (p=0.34).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, almost 60% of patients with CD were found to be vitamin D deficient or insufficient. Among patients with an autoimmune disorder, after adjusting for age of CD diagnosis and gender, vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency was not associated with any autoimmune disorder. When examining various modes of presentation and specific diseases, vitamin D deficiency was more common in patients who presented with anemia and in those patients with psoriasis, but was far less common in patients who presented with incidentally discovered signs of villous atrophy noted on endoscopy.

Vitamin D is known to be important in the maintenance of bone mineralization, growth, and development but recent research has shifted towards the extraskeletal manifestations of vitamin D deficiency.19 Vitamin D deficiency has been implicated in the pathogenesis of breast, prostate, and colon cancer, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune disorders.14,19 The most well defined autoimmune disorders associated with vitamin D deficiency include multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes and several observational studies have shown that living at higher latitudes increases the risk of developing these autoimmune disorders.31,40 In addition, vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency has been found in patients with autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.30–34, 41

Our study does not support the findings that vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency is associated with autoimmune disorders in patients with CD. There are multiple potential explanations for these findings. First of all, it is possible that the null findings in our study accurately reflect the relationship between vitamin D and autoimmune disorders. The majority of studies citing the relationship between low vitamin D levels and an increased incidence of autoimmune disorders are observational cohort studies.19 There have been several studies testing whether vitamin D supplementation is protective against the development of autoimmune disorders, such as the Nurses’ Health Study, which showed that daily intake of ≥ 400 IU of vitamin D was protective against the development of multiple sclerosis. But there have been no prospective randomized controlled studies supporting these findings.31 These mixed and often inconclusive studies prompted the Institute of Medicine to conclude that the results from these studies could not be used to help develop the dietary intake recommendations for vitamin D and calcium.42 The currently undergoing vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL; Clinicaltrials.gov number NCT01169259) is a randomized study investigating whether vitamin D supplementation can be used for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer with ancillary studies examining whether it decreases the risk of autoimmune disorders. While the VITAL study has begun to address the Institute of Medicine’s call for more conclusive data, the current data available does not clearly address this issue.

Potential unmeasured confounders could also have contributed to the null findings of the study. For example, patients were not excluded from the study if they were taking vitamin D supplements. While we attempted to minimize the effect that this confounder would have on our study by only including the lowest vitamin D level on record for each patient, it likely led to elevated vitamin D levels in some patients. As a result, it is possible that patients became misclassified into the inappropriate vitamin D category, which would have masked the true association between vitamin D and autoimmune disorders.

While no association was found between autoimmune disorders and vitamin D levels, our study did find that vitamin D deficiency was more common in patients who presented with anemia than those patients who did not. Although diarrhea has classically been described as the initial presenting symptom of CD, extra-intestinal manifestations, such as anemia, are becoming more common and can sometimes be the only presenting sign of CD.2, 43 While the pathophysiology of anemia is likely multi-factorial, one widely accepted mechanism is that iron is absorbed by the proximal duodenum, a region of primary involvement in CD and site of fat soluble vitamin absorption.2 Therefore, it is not surprising that patients with CD and anemia might also suffer from vitamin D deficiency. Considering the overlap between anemia and vitamin D deficiency observed in this study, it could be useful to screen CD patients with anemia for vitamin D deficiency.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that involves the activation of both the innate and acquired immunologic systems.41 While the clinical course and treatment for psoriasis vary, topical vitamin D analogs have been shown to be effective for the treatment of psoriatic plaques.41,44 Considering the inflammatory nature of the disease and the improvement with topical vitamin D treatment, vitamin D deficiency has been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. A recent article found that vitamin D deficiency (defined as <20 mg/dL) was present in 25.6% of patients with psoriasis as compared to 9.3% of control patients without psoriasis (p=0.43). 41 These findings are consistent with what was found in our study, which observed that psoriasis was more common among those with vitamin D deficiency, and it continues to support the investigation of vitamin D as a treatment modality for psoriasis.

Although vitamin D deficiency was observed in patients who presented with anemia and those patients who had psoriasis, it was not seen in patients whose CD was diagnosed incidentally on endoscopy. While incidental endoscopic diagnosis of CD has increased since 1993,45 it did not represent a patient group at risk for vitamin D deficiency in our study. This is thought to be because patients who become diagnosed incidentally on endoscopy likely have less severe disease activity. As a result, these patients are less likely to have severe villous atrophy, which would place them at risk for malabsorption and vitamin D deficiency.

There are several limitations in our study. First of all, the study is a retrospective cross-sectional study of patients with CD and their corresponding vitamin D levels. Due to the study design, it is unclear whether patients with low vitamin D levels and no corresponding autoimmune disorder would later develop an additional autoimmune disorder if they were followed over a period of time. The overall generalizability of this study is not known since all patients were seen in a tertiary care center that is a large referral center for the management of CD; as such, it may not be representative of the overall population of CD patients in the US. While the study had a large percentage of patients with autoimmune disorders (10%), there were only 530 patients who had 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on record, possibly making the study underpowered to detect difference small association with AD. Lastly, while all vitamin D levels were done at the same laboratory, vitamin D levels included in this study were measured at different time points in the patients’ illness, without knowledge of their diet, medications, or dietary supplementations. Patients could have had prior 25-hydroxyvitamin D checks from their primary care physician that were not included our laboratory, and therefore, could not be accessed for this study.

In conclusion, we found no association between vitamin D levels and autoimmune disorders in patients with CD. Low vitamin D levels were observed in patients who presented with anemia and in those patients who had psoriasis. Assessment of vitamin D deficiency appears to be a high yield practice in CD, especially those patients who present with anemia.

Abbreviations

- CD

Celiac Disease

- AD

Autoimmune diseases

- CUMC

Columbia University Medical Center

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Grant Support:

BL: the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (KL2 RR024157). No declared conflicts of interest for the authors of this paper.

Citations

- 1.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac Disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357 (17):1731–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez L, Green PH. Extraintestinal manifestations of celiac disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8(5):383–389. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai D, Brar P, Holleran D, et al. Effect of gender on the manifestations of celiac disease: evidence for greater malabsorption in men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(2):183–187. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sategna C, Solerio E, Scaglione N, et al. Duration of gluten exposure in adult coeliac disease does not correlate with the risk for autoimmune disorders. Gut. 2001;49(4):502–505. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson A, West J, Aithal GP, et al. Autoimmune cholestatic liver disease in people with coeliac disease: a population-based study of their association. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(4):401–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickey W, McMillan SA, Callender ME. High prevalence of celiac sprue among patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(1):328–329. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talal AH, Murray JA, Goeken JA, et al. Celiac disease in an adult population with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: use of endomysial antibody test. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(8):1280–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iltanen S, Collin P, Korpela M, et al. Celiac disease and markers of celiac disease latency in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(4):1042–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Leary C, Walsh CH, Wieneke P, et al. Coeliac disease and autoimmune Addison’s disease: a clinical pitfall. QJM. 2002;95(2):79–82. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojetti V, Aguilar J, Guerriero C, et al. High prevalence of celiac disease in psoriasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2574–2575. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ventura A, Magazzu G, Greco L. Duration of exposure to gluten and risk for autoimmune disorders in patients with celiac disease. SIGEP study group for Autoimmune Disorder in Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(2):297–303. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosnes J, Cellier C, Viola S, et al. Incidence of autoimmune diseases in celiac disease: protective effect of the gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(7):753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roston A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1981–2002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGreevy C, Williams D. New insights about vitamin D and cardiovascular disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155:820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoenfeld N, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y. The effect of melanism and vitamin D synthesis of the incidence of autoimmune disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2009;5(2):99–105. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albert PJ, Proal AD, Marshall TG. Vitamin D: the alternative hypothesis. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8(8):639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toubi E, Shoenfeld Y. The role of vitamin D in regulating immune responses. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12(3):174–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerner A, Shapira Y, Agmon-Levin N, et al. The clinical significant of 25OH-Vitamin D status in celiac disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8237-8. [EPub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen CJ. Clinical practice: Vitamin D insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3):248–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1009570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnson Y, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y. Vitamin D and autoimmunity: new aetiological and therapeutic considerations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1137–1142. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Etten E, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97(1–2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue ML, Zhu H, Thakur A, et al. 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression in human corneal epithelial cells colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80(4):340–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.80.4august.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stockinger B. Th17 cells: an orphan with influence. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85(2):83–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linker-Israeli M, Elstner E, Klinenberg JR, et al. VitaminD (3) and its synthetic analogs inhibit the spontaneous in vitro immunoglobulin production by SLE-derived PBMC. Clin Immunol. 2001;99(1):82–93. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San-Pedro JI, Bilbao JR, Perez de Nanclares G, et al. Heterogeneity of vitamin D receptor gene association with celiac disease and type I diabetes mellitus. Autoimmunity. 2005;38(6):439–444. doi: 10.1080/08916930500288455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naderi N, Farnood A, Habibi M, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms in Iranian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(12):1816–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Haguchi LM, et al. Higher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(3):482–489. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes CE, Cantorna MT, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;216(1):21–27. doi: 10.3181/00379727-216-44153a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munger KL, Levin LI, Hollis BW, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2832–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nieves J, Cosman F, Herbert J, et al. High prevalence ofvitamin D deficiency and reduced bone mass in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1995;44(9):1687–92. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munger KL, Zhang SM, O’Reilly E, et al. Vitamin D intake and incidence of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62(1):60–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000101723.79681.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cutolo M, Otsa K, Uprus M, et al. Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;7(1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merlino L, Curtis J, Mikuls T, et al. Vitamin-D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Iowa women’s Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(1):72–77. doi: 10.1002/art.11434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birlea S, Costin G, Norris D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the action of vitamin-D analogs targeting vitiligo depigmentation. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(4):345–359. doi: 10.2174/138945008783954970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA., Jr Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 209;169(6):626–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. What we eat in America. 2005–2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holic MF. Vitamin D Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stenson WF, Newberry R, Lorenz R, et al. Increased prevalence of celiac disease and need for routine screening among patients with osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):393–399. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stazi AV, Trecca A, Trinti B. Osteoporosis in celiac disease and in endocrine and reproductive disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(4):498–505. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1080S–6S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orgaz-Molina J, Buendia-Eisman A, Arrabal-Polo MA, et al. Deficiency of serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in psoriatic patients: A case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute of Medicine. Report Brief: Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. 2010 http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2010/Dietary-Reference-Intakes-for-Calcium-and-Vitamin-D.

- 43.Leffler D. Celiac Disease Diagnosis and Management: A 46-year old woman with anemia. JAMA. 2011;306(14):1582–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.306.14.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stern RSS. Psoralen and Ultraviolet A light therapy for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:682–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct072317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B, et al. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(2):395–398. doi: 10.1023/a:1021956200382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]