Abstract

The use of culturally sensitive intervention could improve mental health care for the eating disorders treatment in the Latino population. The aim of this report is to describe the rationale, design, and methods of the ongoing study entitled “Engaging Latino families in eating disorders treatment.” The primary aim of the study is to compare (a) the combined effect of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa (CBT-BN) that has been previously adapted for the Latino population plus Family Enhanced (FE) modules, with (b) the standard adapted individual CBT-BN in a proof-of-principle study with 40 Latina adults with eating disorders and one relative or significant other per patient. We hypothesize that 1) the feasibility, acceptability, and adherence of participants in CBT-BN+ FE will be superior to individual CBT-BN only; 2) relatives in CBT-BN+ FE will report greater treatment satisfaction, greater reduction in family conflict, and greater decreases in caregiver burden than relatives in the individual CBT-BN only condition; and 3) patients who participate in CBT-BN+ FE will show trends towards greater decreases in ED symptoms compared with patients in CBT-BN only; although power will be limited to detect this difference. However, we predict that they will show greater retention in treatment, greater treatment satisfaction, and greater decreases in family conflict than patients in CBT-BN only. The completion of this investigation will yield important information regarding the acceptability and feasibility of a culturally sensitive evidence-based treatment model for Latinos with eating disorders. (Word Count=240)

Keywords: Latinas, Eating disorders, Cultural adaptation, Family intervention, Clinical trial, Cognitive-behavioral therapy

1. Introduction

Although the Latinos are the largest minority population in the United States, the health disparities between this population and the majority are concerning, especially regarding psychiatric disorders [1]. For example, Latinos/as usually are underrepresented in outpatient settings [2] and are less likely than non-Latino whites to receive best care practices [2–4]. This is in addition to the specific health-seeking patterns in this population, characterized by underutilization of mental health services, premature treatment termination, and frequent treatment drop out in comparison to non-Latino whites [5, 6]. Addressing health disparities in this population is essential [1].

The use of culturally sensitive help-seeking pathways could improve the practice of mental health care in order to make services more accessible and effective for underserved populations [7]. Regarding help-seeking pathways, López and collaborators [1] discussed four main points that could decrease health disparities among populations. First, limited mental health literacy should be addressed due to the low use of mental health care in Latinos/as. Second, to facilitate pathways to care, it is important to increase social networks. Given that family close interpersonal relationships are important cultural values in Latinos/as, the inclusion of family or significant others in care pathways could provide the support that patients need to engage and remain in treatment. Third, consistent with the second point, the inclusion of family in psychoeducation and skill training appears to be an important cultural adaptation in the Latino population [1, 8, 9]. Finally, synchronous interventions across pathways to care should be considered. Pathways must be developed that respond to the reality of the Latino population (i.e., lack of health insurance, different health-seeking patterns, among others) in order to maximize the resources and address the specific needs of the target population. Culturally sensitive protocols or guidelines as an adjunctive intervention to evidence-based treatment appear to facilitate engagement in treatment and may enhance outcomes in minority populations [10].

Specifically, in the treatment of eating disorders (EDs), the inclusion of culture, context, and language are essential considerations for culturally competent care [11]. However, cultural adaptation for Latinos/as in the United States constitutes a challenge considering the rich cultural and historical diversity among Latino subgroups and the complexity of the acculturation process. The role of family, migration, language, and specific cultural values (e.g., familismo, ethnic identity, dependence, independence) differs depending on the length of time an individual has spent in the United States, as well as on his or her experience of migration, their ancestry, and relationship to the dominant majority culture [12]. The estimated lifetime prevalence of EDs in the Latino population in the United States is on par with the Caucasian population (anorexia nervosa, AN:0.08%; bulimia nervosa, BN:1.61%; binge eating disorder, BED:1.92%; any binge eating: 5.61%) [13]. Risk for developing EDs is clearly not limited to Caucasians, but limited access to care can be a barrier to the utilization of services for EDs [14]. For example, Latinos/as with a history of EDs are less likely to utilize mental health services [15] and to be referred for further evaluation [16, 17] in comparison to non-Latino Whites. However, there is a need for more detailed research on the assessment and treatment of EDs on the Latino population in this country. Differences in the presentation of EDs in Latinos/as may also challenge detection of symptoms in Latinos/as [13]. A culturally sensitive intervention model is necessary to address the health disparity in this population. Especially in the Latino population, the community-based approach seems to be the most responsive model considering the hesitation that many Latinos/as—especially those who are undocumented—have in interacting with governmental agencies [18, 19].

Due to the lack of research on culturally focused interventions for EDs in the Latino population in the United States, the intention of the current study is to document pathways of care for EDs among the less acculturated Latinas in this country.

2. Objective of the clinical trial

The aim of this report is to describe the rationale, design, and methods of the ongoing study entitled “Engaging Latino families in eating disorders treatment.” Considering the stigma associated with mental health in the Latino population and specifically with EDs, we actively selected a less stigmatizing name, “Promoviendo una Alimentación Saludable”-PAS Project (Promoting healthy eating patterns), henceforth referred to as the PAS Project. The primary aim of the PAS Project is to compare (a) the combined effect of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa (CBT-BN) that has been previously adapted for the Latino population [20] plus Family Enhanced (FE) modules, with (b) the standard adapted individual CBT-BN in a proof-of-principle study with 40 Latina adults with EDs and one relative or significant other per patient. The aim is to evaluate feasibility, acceptability, and clinical outcomes preliminarily in patients and family functioning and caregiver burden in participating relatives. This study is designed explicitly to gather preliminary outcome data to inform sample size and power calculations for a subsequent larger randomized controlled trial. The primary patient outcome is acceptability, adherence to treatment, and family function. Secondary patient outcomes include binge-purge episodes per day/week, depression, and anxiety. This study has three hypotheses:

Hypothesis # 1 (primary): The feasibility, acceptability, and adherence of participants in CBT-BN+ FE will be superior to individual CBT-BN only.

Hypothesis # 2: (secondary): Relatives in CBT-BN+ FE will report greater treatment satisfaction, greater reduction in family conflict, and greater decreases in caregiver burden than relatives in the individual CBT-BN only condition.

Hypothesis # 3 (secondary): Patients who participate in CBT-BN+ FE will show trends towards greater decreases in ED symptoms compared with patients in CBT-BN only; although power will be limited to detect this difference due to the sample size. However, we predict that they will show greater retention in treatment, greater treatment satisfaction, and greater decreases in family conflict than patients in CBT-BN only.

3. Methods and Design

3.1. Overview of PAS

The PAS Project comprises a series of investigations in order to tailor the development of a culturally appropriate family-based adjunct intervention to CBT-BN for adult Latina patients with EDs. The study design is an incremental four-phase research plan with a specific focus on developing, refining, and evaluating an FE adjunct to a previously culturally-adapted individual cognitive-behavioral intervention for EDs in Latinas. The three initial phases represent formative work that culminates in the final phase which consists of a proof-of-principle study comparing CBT-BN + FE with traditional individual CBT-BN using a community-based approach.

Phase 1

During this phase, in-depth interviews were conducted with 5 Latinas with either a current or past ED, and 5 mental health providers who serve the Latino community in order to gather comprehensive qualitative information about the appropriate role for family members in treatment of EDs with Latina adults. The mean age of the patients was 31.2 years old. Four Latina patients were immigrants from Mexico, and one was born in the U.S. They had lived in the U.S. between 3 to 33 years. In terms of the ED history, three patients presented with a previous diagnosis of BN, one with BED, and another with binge-eating behavior. The mean age of the mental health care providers was 36.4 years. All of the mental health care providers had either a masters or doctoral degree in social work or counseling with a mean of 7 years of experience working with the Latino population. Interviews were conducted in Spanish by the PI and a trained research assistant using open-ended questions that included five main topic areas for patients: general needs, facilitators and barriers to EDs treatment, familial and other sources of support, previous experiences with treatment, and treatment expectations. For providers discussion topics included: facilitators of engagement and retention, family dynamics, expectations of treatment, the delivery of evidence-based treatment, and the treatment of EDs. All interviews were transcribed verbatim by the research team and compared with the original recording by the PI to ensure the integrity of the transcriptions. Three independent bilingual coders conducted the analysis. This phase underscored important factors such as the inclusion of a family member or friend in treatment, a nonjudgmental therapist, and having a safe environment (physically and emotionally) among others that may enhance the engagement and retention of Latinas with EDs in treatment [21].

Phase 2

Based on the information collected during Phase 1, family intervention modules were developed in Phase 2 to use as the adjunctive family intervention to CBT-BN. Family based sessions were developed to address issues related to psycho-education about EDs, communication, sharing thoughts and feelings, problem solving, and parenting skills. These sessions were developed to be flexible depending on which family member would be included in treatment (e.g., partner, parents, siblings, significant other). Content for partner sessions was adapted from a new couple-based cognitive behavioral intervention for anorexia nervosa, UCAN (Uniting Couples in the treatment of Anorexia Nervosa) [22] and in consultation with Dr. Donald H. Baucom, who is an expert in cognitive-behavioral couple-based interventions. Sessions for other family members or significant others were based on previous formative work with Latino families with a family member with EDs [23].

Phase 3

We conducted a pre-test of CBT-BN + FE modules with four Latina patients with EDs to gather detailed feedback from the therapist and participants on the appropriateness of the material, the flow of the intervention, and thoughts regarding which important topics were and were not included. All patients were immigrants from Mexico with a mean age of 29.7 years. All four had had previous psychotherapy experience. Three nutritional counseling sessions with a dietitian were conducted, and psychiatric appointments were scheduled as needed. The pre-test phase also served as a training period for the community-based therapists and included listening to all sessions (by MLR) and some sessions (CMB), face-to-face supervision with MLR and second order supervision with CMB. Therapists provided detailed feedback on the flow and content of the therapy, and the intervention was adjusted accordingly. The intervention and procedures were adapted and refined based on their feedback. The assessment battery also was piloted during this phase; assessments were conducted at baseline, week 6, and post-treatment.

Phase 4

With a new cohort of 40 Latina adults with EDs, a proof-of-principle study is currently being conducted using a community-based approach. We are comparing CBT-BN (19 sessions) + FE (6 sessions) (n=20) versus individually administered CBT-BN (25 sessions) (n=20). Three nutritional counseling sessions with a dietitian will be conducted, and appointments with the study psychiatrist are scheduled as needed. Assessments are conducted at baseline, at week 6, post-treatment, and three-month follow-up. We will analyze the results of the small study in terms of the primary and secondary outcomes after all data are collected.

3.2. Experimental Design

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Verbal informed consent is obtained from patients during a telephone screening and for the treatment phase (Phase 4); written informed consent is collected from both patients and relatives during baseline procedures. The explanation about the study and the informed consent procedure is conducted in the primary language of the patient and family member whether it is English or Spanish.

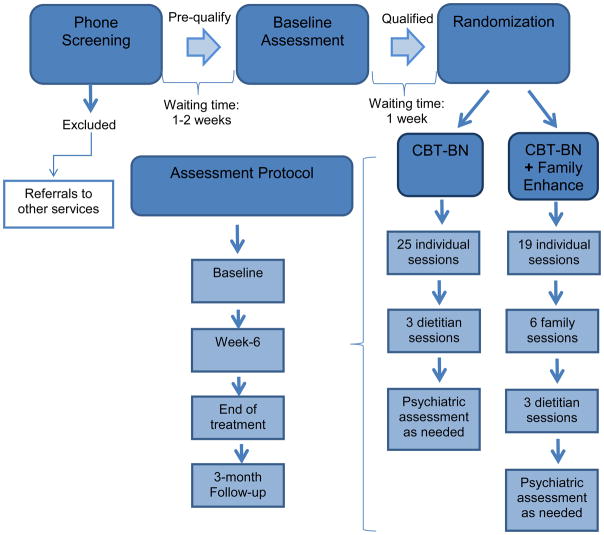

The PAS Project components are presented in Figure 1. The study is a small randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing CBT-BN + FE versus CBT-BN only using a community based approach. Individuals who meet inclusion criteria are randomly assigned to one of two conditions: CBT-BN + FE (n=20) or CBT-BN only (n=20). As a first step, all potential participants who contact the project are offered either a face-to-face or telephone screening. As many Latino patients are cautious about the organized health-care system, the screening includes a description of the program, an introduction to the treatment team, and semi-structured questions designed to establish initial eligibility and to determine the availability of a family member to participate in the study. Participants who appear to be eligible are scheduled for a diagnostic interview during baseline. All patients, regardless of condition are required to have a participating relative, which could include family members (e.g., partner, parents, and siblings) or significant others defined as individuals who play an active role in either emotional or physical support of the patient. After both the patient and the relative are consented and complete their baseline questionnaires, randomization occurs and initial appointments are scheduled for either the CBT+ FE or CBT only condition. A simple randomization procedure is used to allocate participants to treatment condition. A computerized process, integrated into the database system, generates the randomization after documentation of consent is entered.

Figure 1.

PAS Project flow chart

The assessment protocol for both patients and relatives is conducted at baseline, week 6, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up. All measures are administered in Spanish and had been adapted for the Latino population in previous studies. Patient-relative dyads are compensated up to $140 for completion of the assessment battery. The assessment schedule protocol is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

PAS Project Assessment Protocol

| Measures | Source | Baseline | Week-6 | Post-Treatment | 3-month follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary Outcome Measures

| |||||

| Demographic Information | Patient/Relative | X | |||

|

| |||||

| Eating Disorders Examination | Patient | X | X | ||

| Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire | Patient/Relative | X | X | X | X |

| The Familism Scale | Patient/Relative | X | X | X | |

| Family Cohesion | Patient/Relative | X | X | X | |

| Family Burden Interview Schedule- Short Form | Relative | X | X | X | X |

| Family Support Questionnaire | Patient | X | X | X | X |

|

| |||||

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale | Patient/Partner | X | X | X | |

|

| |||||

|

Secondary Outcome Measures

| |||||

| Beck Depression Inventory-Revised | Patient | X | X | X | X |

| Symptoms Check List-36 | Patient | X | X | X | X |

| Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-American II | Patient | X | |||

| Acculturative Distress Scale | Patient | X | X | X | |

|

| |||||

|

Process Measures

| |||||

| Psychotherapy Alliance Scale-10 | Patient/Relative | ||||

| Patient Satisfaction | Patient | X | |||

| Competency Checklist for Cognitive Therapists | Rater | X | |||

3.3. Participants

Forty Latina women and one relative or significant other are being recruited to achieve a total of 80 participants entered into the clinical trial. To facilitate recruitment, strong ties to the Latino community were established during the first three phases of the study. Due to the lack of bilingual resources for Latinos/as with EDs in the area, the PAS Project is considered a referral option by various mental health and primary care providers that serve the Latino population. We will continue to expand this primary network for recruiting Latino participants via outreach to family practices, churches, and other community organizations across the State. We opted to include patients with a threshold diagnosis of BN, sub-threshold BN, and BED in the clinical trial.

This decision is based on three lines of evidence. First, in outpatient settings the most common clinical presentation is EDNOS, followed by BN, and then AN [24]. For Latinos, BED is the most prevalent ED [13, 25]. Second, both phenomenological and treatment outcome studies reveal few differences in clinical severity [26], comorbid psychopathology [27], and treatment outcome [24, 26, 28] between those with threshold and sub-threshold BN. Third, CBT is the treatment of choice for both BN and BED [29, 30], and the CBT upon which this study is based [31] is applicable for both BN and BED. Our experience in the community suggests that this approach will enhance recruitment and reduce the perception of arbitrary cutoffs for participation (e.g., requiring two binges per week leading to the perception that one is not “ill enough” to be invited to participate). Our inclusive approach will decrease any perception of exclusivity which, we believe, will in turn decrease barriers to treatment seeking and health-care utilization. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for PAS Project

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | DSM-IV criteria for: BN, BED, EDNOS (sub-threshold BN) |

| Age | Age 18 or older |

| Ethnicity/sex | Latino female |

| Medication | If on antidepressant medication, has been on a stable dose for at least 3 months prior to participation. |

| Family member | Willing to ask a family member or significant other to participate and the family member agrees. |

|

| |

|

Exclusion Criteria

| |

| Medical condition | Any major medical condition that would interfere with treatment or require alternative treatment (e.g., type 1 diabetes mellitus). |

| Substance abuse | Alcohol or drug dependence in the last three months. |

| Suicide risk | Current significant suicidal ideation reported during the screening or at baseline. |

| Cognitive impairment | Developmental disability that would impair the ability of the participant to benefit from psychotherapy effectively |

| Comorbidity | Psychosis, including schizophrenia, or bipolar I disorder |

| Pregnancy | Pregnant at screening |

| BMI | Body mass index below 17.5 kg/m2 |

| Sex | Male |

| Medication | Patients on antidepressant medication who have not been on a stable dose for three months or taking medications that significantly affect appetite or weight. |

3.4. Measures

Four domains will be assessed; eating disorders symptoms, family relationship, acculturation, and other psychiatric symptoms. Each domain is part of our primary and secondary outcomes. We recognize that the assessment battery is extensive but necessary to assess our four domains. We will also evaluate the utility of these scales for inclusion in a subsequent larger RCT.

3.4.1. Eating disorder symptoms

3.4.1.1. Eating Disorders Examination (EDE; [32]). The EDE is used to establish the DSM-IV diagnosis of eating disorders. This is considered as the gold standard diagnostic measure for EDs. We are using the Spanish version of the EDE which has been adapted for use with Latinas [33].

3.4.1.2. Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q;[34]). The EDE-Q was adapted by Elder and Grilo [35] with monolingual Spanish speaking Latinas. This self-report version of the EDE-Q assesses many of the same variables as the interview. The Spanish version test-retest reliability Spearman rho ranged from 0.71 to 0.81 [35].

3. 4. 2. 1. Comorbid symptomatology

3.4.2.2. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; [36]). The BDI evaluates the severity of depressive symptoms. This Spanish version is a reliable measure that has been used with Latinos/as in major outcome studies of depression [37]. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained for the BDI Spanish version was 0.88 [38].

3.4.2.3. The Symptom Checklist-36 (SCL-36; [39]). This measure generates six separate factor scores (depression, somatization, hostility-suspiciousness, phobic anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity) and one global index of psychopathology. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained for the Spanish version was .94 [38, 40].

3.4.3.1. Family measures

3.4.3.2. Familism Scale (FS; [41]). FS measures values and attitudes toward the family, focusing on identification and attachment between the family members and feelings of family loyalty and reciprocity. The FS has 14 items, and three factors emerge from this scale: family obligations (perceived obligation to provide material and emotional support to the members of the extended family), perceived support from the family, and family as referents (e.g., family members as important influences on behaviors and attitudes). These factors revealed internal consistency with Cronbachs’ alphas of 0.76, 0.70, and 0.64 respectively. The scale exists in both English and Spanish and has been used with various cultural groups.

3.4.3.3. The Family Cohesion scale (FC;[42]). The FC is a seven item measure focused on elements of family closeness and communication such as whether the respondent considers family togetherness to be important. The FC was used in the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 among the Latino population [42].

3.4.3.4. The Family Burden Interview Schedule- Short Form (FBIS-SF; [43]) assesses family burden and coping. The FBIS consists of scales on Impact on Daily Living, and Worry with good internal consistency scores. FBIS-SF evaluates five areas; financial burden, routine family activities, family leisure, family interaction, and effect on physical and mental health of others.

3.4.3.5. Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS;[44]) was developed to assess the quality of the marriage relationship as well as dyads who are living as a couple. The DAS Spanish version is used in the current study [45]. Cronbach’s alphas for the Spanish and English versions were ranging from .74 to .89 [44].

3.4.3.6. The Family Support scale was adapted by the PI from the Therapeutic Alliance Scale [46] to measure the support that the patient perceived about her EDs from the family member or significant other included in the study. The Family Support scale includes 10-items measuring emotional support related to their EDs (e.g., to talk, to seek help, feel understood, among others).

3. 4.4.1. Acculturation Measures

3.4.4.2. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans II (ARSMA-II; [47]). The level of acculturation is assessed with ARSMA-II. This measure is designed to assess multifaceted integrative acculturation which includes; language use and preference, ethnic identity and classification, cultural heritage and behaviors, and ethnic interaction. The internal reliability of this measure using the Cronbach’s alpha is .88 [47].

3.4.4.3. The Acculturative Distress Scale [42]). The ADS is used to measure the stress of culture change that results from immigrating to the U.S. This scale consists of eight items and has been tested mostly with Mexican American samples and has dichotomous response categories of “yes” (1) or “no” (5). This measure was used in the NLAAS study with a Cronbach’s alpha of .70 in the Latino population.

3.4.5.1. Process Measures

3.4.5.2. Patient Satisfaction (PS; [48]). Satisfaction with treatment is being evaluated with an adaptation of the Service Satisfaction Scale. High validity and reliability has been shown with Latinos. The Satisfaction with Perceived Outcome subscale with Cronbach’s alpha of .80 and Practitioner’s Manners and Skills subscale with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87 [49].

3.4.5.3. The Psychotherapy Alliance Scale-10 (PAS-10;[46]) is a 10-item scale measuring therapeutic alliance from the client’s perspective based on the Integrative Psychotherapy Alliance Scale and the Psychotherapy Alliance Scale.

3.4.5.4. Competency Checklist for Cognitive Therapists (CCCT;[50]) is a 16-item scale measuring the competency of therapists whose focus is cognitive behavioral work. A Spanish version of the instrument is available.

For those patients who decide to terminate treatment early, an exit interview is conducted using the Reasons for Refusing Treatment scale. This scale is used in the Institute for Psychological Research at the University of Puerto Rico and was previously used by the PI in the cultural adaptation of CBT-BN in Puerto Rico. This consists of a checklist with 14 reasons for refusal or early termination of treatment and a rating of how influential (on a ten-point scale) each particular reason was in the decision. Discussion of reasons for termination takes place to identify aspects of the treatment that may require changes to maximize acceptability by patients. For those patients who complete the treatment protocol, an exit interview is conducted using the Reasons for Continuing Treatment. Due to the lack of information about which factors contribute to retention in treatment in the Latino population, the PI adapted the Reasons for Refusing Treatment Scale in order to explore which factors contributed the most to retention into treatment.

3.5. Community based approach

A community-based approach was chosen based on the qualitative interviews conducted with Latinos/as during Phase 1, in which they emphasized that community centers represent safe havens for them. Three sites of a community based non-profit mental health clinic are serving as the primary settings for the PAS Project. This clinic is well established in the community and has a good reputation in the Latino population. Two therapists from that clinic with Master’s degrees in social work and one psychiatrist were recruited to serve as therapists for the trial. In order to minimize gas and transportation costs and logistical problems that could undermine treatment continuation, we have established sites around the Raleigh-Siler City-Durham-Chapel Hill area.

3.6. Treatment Intervention

CBT-BN is a semi-structured and problem-oriented intervention that is focused on the patient’s present and future rather than his or her past [31]. Twenty-five sessions are divided into three stages. The cognitive perspective about ED symptom maintenance is presented during the first phase, and behavioral techniques are used to replace binging and purging behaviors with a stable pattern of regular eating (sessions 1 through 11). In the second phase (sessions 12 through 22), particular emphasis is on the elimination of dieting with the use of cognitive procedures and the identification of thoughts, beliefs, and values that perpetuate EDs behaviors. The final phase (sessions 23 through 25) is aimed at upholding positive changes made during treatment [51]. Each session is about 50 minutes long, over a period of 27 weeks. Spanish versions of the CBT-BN therapists’ manual and patient manual [52] are used with recommendations based on the cultural adaptation conducted with Latinas with EDs in Puerto Rico [31]. Participants from each treatment condition (CBT-BN and CBT-BN + FE) receive the same core content of CBT-BN. Six family based sessions were developed to be delivered as an adjunctive intervention to 19 individual sessions of CBT-BN. The content of sessions include psychoeducation about EDs, practical information about how to deal with a family member with EDs, and strategies to reduce caregiver burden. Additional content includes, explanations about the condition, consequences of the illness, factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of EDs, what to expect from treatment, what to expect in terms of recovery process, and misperceptions and stigma about EDs and mental health care. Specific content and approach varies depending on the family member involved. For spouses/partners, sessions are focused on general couple functioning including communication, sharing thoughts and feelings, and problem solving as well as EDs specific topics such as eating together, body image, and intimacy, some of them adapted from UCAN [22]. For extended family, important areas include family communication, reduction of conflict and coercive family interactions, establishing healthy boundaries between family members, building trust in relationships and supporting autonomy, recognizing family patterns that can exacerbate EDs (family that emphasizes dieting, body image, disturbed eating behaviors), problem solving skills and supportive positive conflict resolution methods [23]. By recognizing the impact of EDs on the family and providing specific strategies for family members to deal with the patient and her EDs, the intention is to provide the necessary skills to be a source of support for the patient during treatment.

3.7. Therapy Sessions

3.7.1. Therapist training and supervision

The PI, who has extensive experience conducting CBT-BN in the Latino population, and two bilingual therapists from the non-profit community based mental health clinic, are conducting the treatment. The therapists from the community received 20 hours of training on CBT-BN, and each completed one practice case from the pilot test phase (Phase 3). The training included careful preparatory reading of the manual and assigned readings, didactic presentation of manual components, review of audiotapes, and role plays. All therapy sessions are digitally audio-recorded for supervision and protocol adherence coding. Therapy is conducted in Spanish or English depending on the preference of the patient and family member. Recordings are reviewed by the PI weekly for supervision and feedback is provided. For therapy sessions conducted by the PI, feedback is provided by the primary mentor (CMB).

3.7.2. Monitoring therapist adherence

Adherence scales have been developed for both the individual CBT and the FE modules. Audiotapes for CBT only and CBT+ FE are rated for fidelity to treatment condition by blinded raters using an adaptation of the Collaborative Study Psychotherapy Rating Scale (CSPRS) [53] used in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Therapist competency is being evaluated using the Competency Checklist for Cognitive Therapists [50]. The following factors are assessed: establishment of rapport, responsiveness to patients’ concerns, communication of interest in patients’ experiences and feelings, capacity to listen empathetically, ability to follow manual and session’s focus, and development of treatment alliance. The cultural and social contexts are also considered. Competency requires the use of examples, expressions, and vocabulary that will be understood by the patients in a culturally appropriate context. Competency is evaluated by trained research assistants following the same procedure as the adherence evaluations. Trained objective raters rate three randomly selected tapes from each case. Tapes come from early, middle, and late phases of treatment. As a further method of monitoring treatment integrity, the supervisor (MLR or CMB) rates two sessions per case for adherence and competency. As an added measure, therapists are asked to rate themselves after each session on the procedures that they administered. Although this later approach is potentially biased, it helps the therapist/facilitators keep the essential features of the model clearly in mind [54].

3.7.3. Nutritional counseling sessions and medical assessment

Three nutritional counseling sessions are provided to each patient. A bilingual licensed and registered dietitian with Latino background was recruited to conduct these sessions. Considering food as central for Latino families and for their traditions, it is important to integrate professionals in this field with background knowledge and understating about food preferences and the role of food in the Latino culture. Patients often are more comfortable with a dietitian familiar with their culture and the role that food plays in it.

Psychiatry appointments are conducted by a bilingual psychiatrist from the community mental health clinic. Those patients who present with significant symptoms of depression or anxiety are referred for a psychiatric evaluation. The Medical Director of the UNC Eating Disorders Program, who is a member of Data Safety Monitoring Committee for the current study, is available for consultation for the psychiatrist from the mental health clinic. For any other health problems related to the EDs, patients are referred to the UNC Center for Latino Health (CELAH). In this study, many participants are likely to be uninsured and not have their own primary care provider. The UNC-CELAH Clinic has agreed to provide medical support on a sliding scale for the participants in the study. Both psychiatric and medical evaluations, if needed, are covered by the PAS Project.

4. Analysis

Descriptive statistics are being compiled both by treatment group and for the combined sample. These analyses provide a means of identifying miscoded data or incorrect data entries, and will provide a method for evaluating the extent of missing data and the distribution of primary and secondary outcome measures. Outcome variables (frequency of binging and purging episodes) will be evaluated for possible transformation on the basis of distributional characteristics (e.g., skew, kurtosis).

Baseline comparisons between the CBT + FE and CBT only conditions will be made on demographics, diagnostic information, as well as all primary and secondary measures of outcome using independent sample t-tests for symmetrically distributed continuous measures, Mann-Whitney for ordinal measures and randomization tests for non-symmetrically distributed continuous measures, and Fisher exact tests for nominal measures. Clinically relevant variables (as judged by the investigators) that differ by group will be considered for use as covariates in subsequent analyses. These tests will have low power to detect anything but large effects due to the small sample size in this proof-of-principle study; hence, failure to reject any null hypotheses clearly is not meant as evidence that no difference exists. P-values from these tests will be considered to be simply further descriptive statistics. We will measure a number of other variables and will calculate the same descriptive statistics as mentioned above, by treatment group and time point.

Outcome analyses will focus on estimating the magnitude (rather than the statistical significance) of differences observed between CBT + FE and CBT only conditions, with confidence intervals where appropriate. Anticipating that we will be unlikely to find statistically significant differences between the treatment modalities because CBT has demonstrated efficacy for treating BN and BED, we will focus the analysis primarily on the process variables (e.g., treatment acceptability, retention in treatment, family measures).

4.1. Introduction to Power and Sample Size

We used SAS® Proc Power, NQuery Advisor, and UnifyPow software for power and sample size calculations. We examined power and sample size for Hypothesis 1 in the context of a two-group ANOVA on change scores. Due to the lack of preliminary data (which we will gather in this project), we simply examined power to detect effect sizes characterized by Cohen as “small,” “medium,” or “large and very large.” This is less than satisfactory, in that it does not express effects in terms of clinically and scientifically meaningful sizes in the metric of the instrument to be used. However, when the instrument has not been used sufficiently previously to develop commonly accepted standards for clinically and scientifically meaningful effect sizes; this is the only way to explore their development. To be able to detect very large effect sizes, we would require 21 participants per group. To be able to detect large effect sizes, we would require 26 participants per group. To be able to detect medium effect sizes, we would require 45 participants per group. To be able to detect small effect sizes, we would require 176 participants per group. With only 20 subjects per group, it is obvious that this study will be able to detect only extremely large effect sizes.

4. 2. Data Safety and Monitoring Plan

A Data Safety Committee (DSC) provides oversight and monitoring of this intervention study to ensure the safety of participants and the validity and integrity of the data. Quarterly reports are submitted to DSC members regarding study progress. All potential adverse effects are reviewed by the DSC, in addition to being submitted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill IRB. Complaints from the patients are reported to the DSC. Following the receipt of each quarterly report, quarterly conference calls are held to review study progress. In addition, DSC members are available for additional consultation on an as-needed basis. There are multiple purposes of this DSC. The DSC can monitor and advise on scientific, clinical, and ethical issues related to study implementation for the protection of human subjects. This includes an evaluation of various aspects of preventive interventions for suicidal and abused persons, including intervention side effects, lack of intervention response, an increase in Axis I symptoms, serious victimization, and police involvement. A review of this information may lead to recommendations regarding the continuation, modification, or termination of the study. The DSC also oversees the quality of data collection, management, and analysis. The DSC also monitors and advises key personnel on ethical issues related to adverse events.

The DSC is responsible for monitoring the safety of subjects in the study and tracking any adverse events such as increasing bulimic or suicidal symptoms. Specific information about adverse events is recorded on an Adverse Event Case Report form. All adverse events are evaluated by the PI and the DSC, and serious adverse event are reported to the DSC, IRB and NIMH within 24 hours.

5. Discussion

Studies documenting racial/ethnic differences in treatment outcomes for EDs are scarce. A recent study exploring race/ethnicity as a moderator of treatment outcomes found that race/ethnicity significantly predicted dropout from treatment for BED, especially in African Americans [55]. However, it is important to mention that Hispanic/Latino samples across clinical trials for BED are small, so differences in this population could be undetected [55] and are not necessarily representative of the Hispanic/Latinos who are presenting in community settings [56]. More research is needed to better understand treatment responses with less educated and acculturated Hispanic/Latinos who are more commonly treated in community settings. Consistent with the literature about treatment seeking patterns [57], Hispanic/Latinos are presenting with greater eating and body image concerns in comparison with Caucasians and African Americans [56]. It is important to acknowledge the complexity of cultural factors in order to develop culturally sensitive interventions to address race/ethnic differences in treatment response.

The current study is one incremental but important step towards decreasing the health disparities in Latinas with EDs. This study is focused on three culturally specific areas in the treatment of EDs; a) content—providing a treatment which integrates the cultural values of Latinos (e.g., familism); b) process—matching the patient with a therapist who has experience working with Latinos and is sensitive to their cultural values and language; and c) delivery—using a community-based model to enhance treatment engagement by providing a safe setting. However the implementation of evidence-based intervention in the community settings is not free of challenges.

First, it is important to promote literacy among health and mental health providers as well in the Latino population in order to be aware that EDs do occur in Latinos/as. Primary care settings play a key role in early detection of emotional distress due to the common somatization and the mental health stigma among Latinos/as [58, 59]. Second, the gap between the research and clinical practices should be addressed. Culturally sensitive evidence-based interventions could have a greater chance to be adopted by clinicians in community settings if they allow sufficient flexibility to deal with the realities of the target population. For example, not all Latinos/as could afford weekly sessions due to double work shifts or financial stressors and family conflict requires intervention with multiple family members, among other issues. One specific challenge that has been observed in this ongoing study is the high frequency of trauma in Latinas with EDs. Sexual abuse-related traumas and being re-victimized during border crossings are among the most common traumas reported in the current cases. For those patients with severe trauma, the therapists have struggled to maintain their focus on ED symptoms due to the urgency of active trauma symptomatology. Future directions in the treatment of EDs with Hispanic/Latinas could require a comprehensive assessment and the integration of trauma intervention for those with trauma histories.

From the community mental health perspective, their experience with the population (i.e., how to engage and retain the population in services, resources, dissemination of services, community trust, etc.) should be recognized and respected by researchers in order to develop a partnership that promotes the best practices of care. More attention to effectiveness research is required to explore the best ways in which evidence based treatment can be integrated into community-based service provision, thereby decreasing the gap between the research and clinical practice as well as developing better practices to disseminate the results and make the interventions accessible for patients in community settings.

5.1 Conclusion

Completion of the four Phases of this investigation will yield important information regarding the acceptability and feasibility of a culturally sensitive evidence-based treatment model for Latinos with EDs. Results will inform whether this approach is worthy of testing in a larger community-delivered RCT. A community-based approach represents a practical treatment model designed to enhance engagement and retention in treatment while delivering a high-quality mental health intervention.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by an NIMH grant (K23-MH087954) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The NIMH had no further role in study design; in collection; analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mae Lynn Reyes-Rodríguez, Email: maelynn_reyes@med.unc.edu.

Cynthia M. Bulik, Email: cbulik@med.unc.edu.

Robert M. Hamer, Email: hamer@unc.edu.

Donald H. Baucom, Email: dbaucom@email.unc.edu.

References

- 1.Lopez SR, Barrio C, Kopelowicz A, Vega WA. From documenting to eliminating health disparities in mental health care for Latinos. Am Psychol. 2012;67:511–23. doi: 10.1037/a0029737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, Ortega AN. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psych Serv. 2002;53:1547–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sue S, Zane N, Young K, Bergin AE, Garfield SL, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior, change. 4. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psych. 2001;58:55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A Report of Surgeon General, Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity -A Supplement to Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alegria M, Cao Z, McGuire TG, Ojeda VD, Sribney B, Woo M, Takeuchi D. Health insurance coverage for vulnerable populations: Contrasting Asian Americans and Latinos in the United States. Inquiry. 2006;43:231–54. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_43.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogler LH, Cortes DE. Help-seeking pathways: a unifying concept in mental health care. Am J Psych. 1993;150:554–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markowitz JC, Patel SR, Balan IC, Bell MA, Blanco C, Yellow Horse Brave Heart M, Sosa SB, Lewis-Fernandez R. Toward an adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy for Hispanic patients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiat. 2009;70:214–22. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramirez Garcia JI, Chang CL, Young JS, Lopez SR, Jenkins JH. Family support predicts psychiatric medication usage among Mexican American individuals with schizophrenia. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2006;41:624–31. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang WC, La Framboise T. State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:113–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reyes-Rodríguez M, Bulik CM. Toward a cultural adaptation of eating disorders treatment for Latinos in United States. Mex J Eat Disorder. 2010;1:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernal G, Reyes-Rodriguez ML. Psychosocial treatments for depression with adult Latinos. In: Aguilar-Guaxiola Sergio A, Gullotta Thomas P., editors. Depression in Latinos: Assessment, Treatment and prevention. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng XL, Striegel-Moore R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. Int J Eat Disorder. 2007;40 (Suppl):S15–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snowden LR, Yamada AM. Cultural differences in access to care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:143–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen CN, Fang A, Chosak A, Diniz JB. Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: Implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disorder. 2011;44:412–20. doi: 10.1002/eat.20787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker AE, Franko DL, Speck A, Herzog DB. Ethnicity and differential access to care for eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disorder. 2003;33:205–12. doi: 10.1002/eat.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franko DL, Becker AE, Thomas JJ, Herzog DB. Cross-ethnic differences in eating disorder symptoms and related distress. Int J Eat Disorder. 2007;40:156–64. doi: 10.1002/eat.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz VA., Jr Cultural factors in preventive care: Latinos. Primary care. 2002;29:503–17. viii. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(02)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheppers E, van Dongen E, Dekker J, Geertzen J, Dekker J. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: A review. Fam Pract. 2006;23:325–48. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reyes-Rodríguez ML, Rosselló J, Matos-Lamourt A. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa in Latinos: Cultural Adaptation and Pilot Study (Oral Presentation). International Conference on Eating Disorders of the Academy for Eating Disorders; Barcelona, Spain. 2006, June. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reyes-Rodríguez M, Ramírez J, Patrice K, Rose K, Bulik CM. Exploring barriers and facilitators in the eating disorders treatment in Latinas in the United States. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulik CM, Baucom DH, Kirby JS, Pisetsky E. Uniting Couples (in the treatment of) Anorexia Nervosa (UCAN) Int J Eat Disorder. 2011;44:19–28. doi: 10.1002/eat.20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guadalupe-Rodríguez E, Reyes-Rodríguez M, Bulik CM. Puerto Rican eating disorders treatment: The role of family. RePS. 2011;22:7–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Wales JA, Palmer RL. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiat. 2008;166:311–319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgibbon ML, Spring B, Avellone ME, Blackman LR, Pingitore R, Stolley MR. Correlates of binge eating in Hispanic, black, and white women. Int J Eat Disorder. 1998;24:43–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199807)24:1<43::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krug I, Casasnovas C, Granero R, Martinez C, Jimenez-Murcia S, Bulik CM, Fernandez-Aranda F. Comparison study of full and subthreshold bulimia nervosa: Personality, clinical characteristics, and short-term response to therapy. Psychother Res. 2008;18:37–47. doi: 10.1080/10503300701320652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.le Grange D, Binford RB, Peterson CB, Scrow SJ, Crosby RD, Klein MH, Bardone-Cone AM, Joiner TE, Mitchell JE, Wonderlich SA. DSM-IV threshold versus subthreshold bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disorder. 2006;39:462–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nevonen L, Broberg AG. A comparison of sequenced individual and group psychotherapy for patients with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disorder. 2006;39:117–27. doi: 10.1002/eat.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Binge eating disorder treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disorder. 2007;40:337–48. doi: 10.1002/eat.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Bulimia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disorder. 2007;40:321–36. doi: 10.1002/eat.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairburn CG, Cooper ZT. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyes-Rodríguez ML, Rosselló J, Calaf M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa in Latinos: Preliminary findings of case studies. Poster presented at the Eating Disorders Research Society, Annual Meeting; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 2005, September. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disorder. 1994;16:363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elder KA, Grilo CM. The Spanish language version of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire: Comparison with the Spanish language version of the eating disorder examination and test-retest reliability. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock JE, Erbaugh JK. An Inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Santiago E. Psychometric properties of the BDI and SCL-36 in a Puerto Rican sample (in Spanish) Rev Lat Am Psicol. 1995;27:207–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonilla J, Bernal G, Santos A, Santos D. A revised Spanish version of the Beck Depression Inventory: Psychometric properties with a Puerto Rican sample of college students. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60:119–30. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNeill D, Greenfield T, Attkison C, Binder R. Factor structure of brief checklist for acute psychiatric inpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45:66–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198901)45:1<66::aid-jclp2270450109>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnorm Child Psych. 1995;23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alegria M, Vila D, Woo M, Canino G, Takeuchi D, Vera M, Febo V, Guarnaccia P, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Shrout P. Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. Int J Meth Psych Res. 2004;13:270–88. doi: 10.1002/mpr.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tessler RT, Gamache G. The Family Burden Interview Schedule—Short Form (FBIS/SF) 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976;38:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Youngblut JM, Brooten D, Menzies V. Psychometric properties of Spanish versions of the FACES II and Dyadic Adjustment Scale. J Nurs Meas. 2006;14:181–9. doi: 10.1891/jnm-v14i3a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernal G, Padilla-Cotto L, Pérez-Prado E, Bonilla J. The psychotherapy alliance:Evaluation and development of instruments (in Spanish) Rev Argent Clín Psic. 1999;8:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cuellar IAB, Maldonado RE. Acculturation rating for Mexican-Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenfield TK, Attkisson CC. Steps toward a multifactorial satisfaction scale for primary care and mental health services. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12:271–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Negrón-Velázquez G, Alegría M, Vera M, Freeman DH. Testing the service satisfaction scale in Puerto Rico. Eval Program Plann. 1998;21:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Doll HA, Davies BA, O’Connor ME. Risk factors for bulimia nervosa: A community-based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:509–17. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reyes-Rodríguez ML, Matos-Lamourt A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: A comprehensive treatment manual. Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: University of Puerto Rico; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hollon S. Final Report: System for Rating Psychotherapy Audiotapes. Bethesda, MD: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carroll KM, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ. Utility of therapist session checklists to monitor delivery of coping skills treatment for cocaine abusers. Psychother Res. 1998;8:307–20. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson-Brenner H, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Grilo CM, Boisseau CL, Roehrig JP, Richards L, Bryson SW, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, Devlin MJ, Gorin AA, Kristeller JL, Masheb R, Mitchell JE, Peterson CB, Safer DL, Striegel RH, Wilfley DE, Wilson GT. Race/Ethnicity, Education, and Treatment Parameters as Moderators and Predictors of Outcome in Binge Eating Disorder. J Consult Clin Psych. doi: 10.1037/a0032946. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franko DL, Thompson-Brenner H, Thompson DR, Boisseau CL, Davis A, Forbush KT, Roehrig JP, Bryson SW, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, Devlin MJ, Gorin AA, Grilo CM, Kristeller JL, Masheb RM, Mitchell JE, Peterson CB, Safer DL, Striegel RH, Wilfley DE, Wilson GT. Racial/ethnic differences in adults in randomized clinical trials of binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;80:186–95. doi: 10.1037/a0026700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caballero AR, Sunday SR, Halmi KA. A comparison of cognitive and behavioral symptoms between Mexican and American eating disorder patients. Int J Eat Disorder. 2003;34:136–41. doi: 10.1002/eat.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Interian A, Ang A, Gara MA, Rodriguez MA, Vega WA. The long-term trajectory of depression among Latinos in primary care and its relationship to depression care disparities. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2011;33:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bauer AM, Chen CN, Alegria M. Associations of physical symptoms with perceived need for and use of mental health services among Latino and Asian Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]