Abstract

Background

An important source of debate in many orthopaedic practices is the choice of performing simultaneous or staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty.

Questions/Purpose

The objective of this meta-analysis is to compare simultaneous bilateral with staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty for peri-operative complication rates, infection rates and mortality outcomes.

Methods

All relevant citations were retrieved from MEDLINE, EMBASE, COCHRANE databases and the unpublished literature. Included studies were assessed for methodological quality and abstracted data was conducted independently by two reviewers. Data was categorized into subgroups and pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird’s random effects model.

Results

A total of 18 articles were identified from 873 potentially relevant titles and selected for inclusion in the primary meta-analyses. The incidence of mortality was significantly higher in the simultaneous group at 30 days (RR [relative risk] 3.67, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.68–8.02, p = 0.001, I2 = 59%, n = 67,691 patients), 3 months (RR 2.45, 95% CI 2.15–2.79, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, n = 66,142 patients) and 1 year (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.66–2.06, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%, n = 65,322 patients) after surgery. However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in regards to in-hospital mortality rates (R 1.18, 95% CI 0.74–1.88, p = 0.48, I2 = 0%, n = 33,814 patients). In addition, there was no increased risk of deep vein thrombosis, cardiac complication, and pulmonary embolism or infection rates in either comparison group.

Conclusions

The results of the analysis suggest that simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty has a significantly higher rate of mortality at 30 days, 3 months and 1 year after surgery, but similar infection and complication rates in comparison to staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty.

Keywords: simultaneous or staged bilateral, total knee arthroplasty, meta-analysis, complication rates, infection, mortality

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a common orthopaedic procedure that is used to treat degenerative joint disease in a variety of patient populations. In 2002, approximately 381,000 total knee procedures were performed in the United States [17]. Knee replacement surgery has been reported in the literature as a cost-effective means of alleviating pain and restoring function in a variety of patients [10, 18].

Approximately one third of knee replacement patients exhibit degenerative joint disease symptoms bilaterally, necessita ting knee replacement procedures in both knees [19]. Surgeons and patients are faced with the option of performing both knee replacement procedures simultaneously under one anaesthetic (simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty) or staging the procedures over a specific time interval (staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty). Advocates of simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty (SBTKA) suggest many advantages, including limiting surgery and anaesthesia to a single event, promoting symmetrical rehabilitation amongst both knees and a reduced length of stay at hospitals, which also translates to lower hospital costs [8, 9, 16, 18]. However, several studies have linked an increased number of complications and mortality events with SBTKA [3, 9, 16, 24].

A major obstacle that surgeons face when evaluating patients for SBTKA or staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty (StBTKA) procedures is the lack of evidence available on these topics. Inconsistencies in study results occur when a small sample size is selected, resulting in underpowered studies that are unable to detect treatment effects.

Evaluation of the current evidence in the form of a systematic review and meta-analysis allows surgeons and patients to make an informed decision about the benefits and risks of bilateral knee replacement procedures. We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate complication, infection, and mortality rates amongst SBTKA and StBTKA. A systematic search strategy was developed to answer the following question: For adult patients undergoing total knee replacements, what is the difference between SBTKA and StBTKA on rates of peri-operative complications, infection and mortality?

Materials and Methods

A systematic search strategy was developed in order to find all relevant articles comparing simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Articles were selected for inclusion if they compared complication rates, revision rates or mortality rates amongst simultaneous and staged procedures. We did not establish criteria for surgical technique, post-operative care, type of prosthesis or length of follow-up. Articles were excluded if: (1) they did not contain information comparing complication rates and mortality amongst patients undergoing SBTKA or StBTKA; (2) other surgical procedures were performed in conjunction with the knee replacement procedures; (3) the studies evaluated SBTKA or StBTKA independently; (4) SBTKA or StBTKA was compared to unilateral total knee arthroplasty (UTKA); (5) the study evaluated non-surgical interventions such as antibiotics, rehabilitation protocols and pharmaceutical interventions; (6) the studies were systematic reviews or book chapters about the topic; (7) the studies were expert opinion pieces, narratives or level V evidence; and (8) the studies were published in a foreign language.

Multiple search strategies were used to identify articles relevant to the research question. The electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and COCHRANE were searched for relevant articles that were published from 1960 up to October 2010. Two reviewers (AB, TC)) also hand-searched the archives of annual meetings of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (2000–2010), the Canadian Orthopaedic Association (2005–2010), the American Academy for Orthopaedic Surgeons (2008–2010) and the Combined Orthopaedic Associations (COMOC) for relevant literature. Additional search strategies included hand searching the bibliographies of previous meta-analysis, review articles and book chapters evaluating SBTKA and StBTKA for relevant titles [4, 25–27].

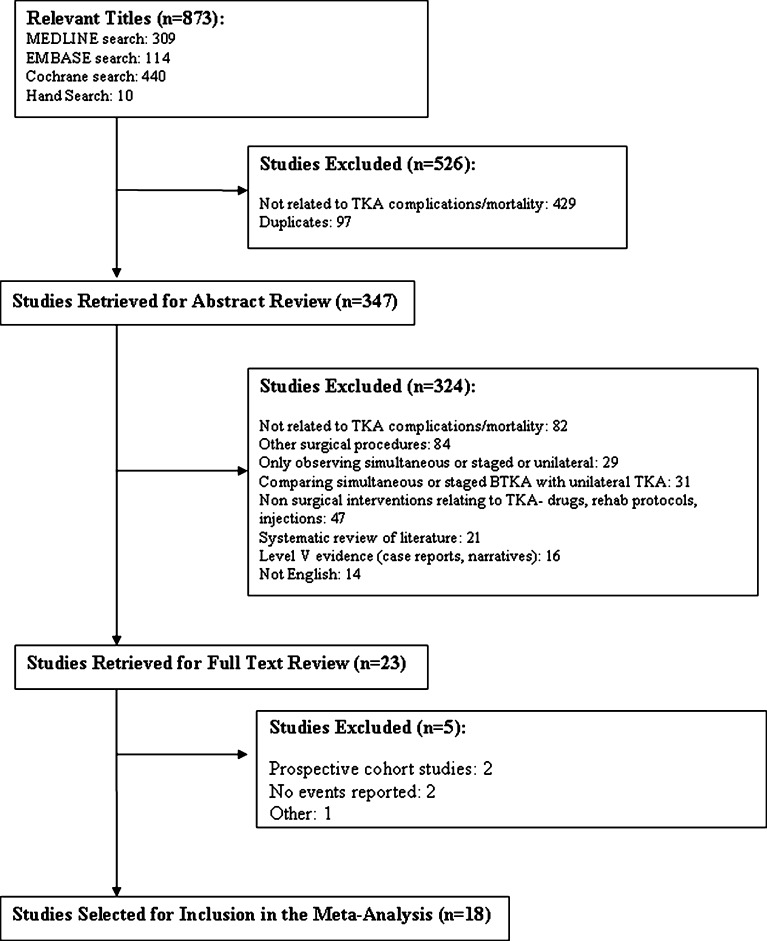

Two reviewers (AB, TC) screened the titles and abstracts of all studies to select relevant articles. All studies were reviewed independently by both reviewers for inclusion (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for identification of studies comparing peri-operative complication rates, revision rates and mortality in simultaneous versus staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty.

In the case of a disagreement, the two reviewers read the full article and discussed until a consensus was reached. If an agreement still could still not be reached, a third reviewer (NH) assessed the article for eligibility. If any additional information in regards to potential studies was needed, the corresponding author of the publication was contacted through email.

Two reviewers (AB, TC) reviewed each article for methodological quality independently. An adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for retrospective studies and prospective studies [35] was developed for the critical appraisal of the included studies. The NOS was developed to assess the quality of nonrandomised studies with respect to study design, study content and generalizability to clinical populations. A scoring system is used to judge each study on three broad categories: selection of the study groups, comparability of the groups and ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest for included studies. One of the items (Adequacy of follow up of cohorts) was deemed irrelevant for the retrospective study design and removed from the scale. Thus, the maximum achievable score for included studies was 8 stars for retrospective studies and 9 stars for prospective studies. For included studies, we considered a score 7 or higher to be reflective of high methodological quality; a score of 5 or 6 reflective of medium quality and a score of 4 or less to be reflective of low methodological quality. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through a consensus process.

The primary outcomes of our study were articles that included information about peri-operative complication rates, mortality and revision rates for patients who received an SBTKA or an StBTKA procedure.

All information relevant to the research question was extracted from the included articles including patient demographics for each treatment arm, location of the study, publication year, methodological quality, reason for total knee arthroplasty, pre-operative co-morbidities, procedure times and type of technique used, total duration of follow-up time, mean length of stay at hospital, complication rates, revision surgery rates and mortality. Two reviewers (AB, TC) reviewed the information in each article and came to a consensus on all extracted information.

A κ (kappa) statistical test was used to determine the extent of agreement amongst individuals who determined eligibility for tests to include in the study. A κ value greater than 0.8 was deemed to represent excellent agreement between the two reviewers. Inter-reviewer agreement was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient to determine concurrence in methodological quality scores. Once again, we selected a criterion of values greater than 0.80 to indicate sufficient agreement between reviewers.

We performed a meta-analysis by pooling outcome measures using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model [5]. The incidence of mortality events, infections, and peri-operative complications including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, cardiac complications and infections were compared in the SBTKA and StBTKA groups.

Unadjusted frequency data about mortality rates, revision rates and peri-operative complications was abstracted from the relevant studies and included in the meta-analysis. We used frequency data to calculate risk ratios and 95% confidence interval (CI) for all primary outcome measures between patients who underwent SBTKA or StBTKA. Review Manager 5.1 was used for statistical analyses. In cases when zero events are reported in both groups, a relative risk (RR) of 1.0 is calculated.

A subgroup analysis was conducted when appropriate in the meta-analysis plots. For mortality rates, studies were grouped according to follow-up times which included in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, 3-month mortality and 1-year mortality rates. Information about peri-operative complications was grouped according to the prevalence of pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis and cardiac complications in patients who underwent SBTKA or StBTKA procedures. Infection rates were grouped into deep infection and superficial infection groups for both treatment arms.

Due to the differences in methodological quality, study design, presence of bias (publication bias, selection bias, attrition bias, etc.), there is a high possibility of heterogeneity in a data when calculating effect sizes. To counter this confounding factor, we performed a stratified analysis using a statistical test of interaction to evaluate the degree to which subgroup results differed from each other [1]. Reasons for heterogeneity in data may include cut off times used to define simultaneous versus staged bilateral TKA (e.g., 2 weeks, 6 months, 1 year), length of follow-up for report of complications and mortality, the year the study was published (before or after the year 2000), location of the study population, age of study population, surgical technique used and methodological quality as assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Even though publication bias could not be adequately assessed in this review due to the limited number of studies in each outcome, we ensured that all citations of included articles were reviewed for eligibility.

In order to control for multiple testing and inflation of type I error, we defined a significant difference between subgroups as p < 0.01. Heterogeneity was classified between studies using an I2 statistic, where an I2 value <25% represents low heterogeneity and an I2 value >75% represents high heterogeneity [11].

Results

The primary literature search identified 873 potentially relevant titles. Twenty-three non-randomized trials [3, 6, 7, 15, 16, 19–24, 28–31, 33, 34, 36] were selected for a full-text review. Twenty-one studies were classified as retrospective studies and two studies were classified as prospective studies [14, 32]. The authors decided to exclude these two studies in order to maintain a low level of heterogeneity since the included studies were already of moderate/poor quality; however, the results from one article [14] were not completely discounted and will be discussed in a later sections of this review. The other prospective study [32] did not sufficiently report patient important outcomes to allow for comparisons to be made. Overall, the results from the two prospective studies are summarized in Table 1. Two studies [9, 12] did not report any events for the primary outcomes and one study [2] compared SBTKA with the first of two staged procedures which resulted in its exclusion from the meta-analysis. Lastly, three studies [6, 21, 24] reported information in regards to revision rates; however this outcome was not pooled as all three studies used different time frames to assess the outcome. As a result, a pooled estimate for this outcome would not have generated a strong measure of association. Hence, a total of 18 studies were selected for inclusion in the meta-analyses. The weighted κ for agreement between reviewers about articles to include in the meta-analysis was 0.896 (95% CI 0.835–0.957) which indicates excellent agreement [14]. The 18 included studies provided information about 108, 212 patients which included 65,265 StBTKA and 42,947 SBTKA procedures (Table 2). Staged procedures were performed anywhere between 3.6 days and 5.9 years. The averaged patient age was 68.8 years (range 19–93 years) and approximately 65.1% of patients were female. Eleven studies were performed at orthopaedic centers in the USA, three at centers in the United Kingdom, and one study each in Australia, South Korea, Sweden and Taiwan. Using an adapted version of the NOS, we classified two studies [7, 22] in the high methodological quality group, 15 studies in the moderate methodological quality group [3, 6, 15, 16, 19–21, 23, 24, 28–30, 33, 34, 36] and one study in the low methodological quality group [31]. There was substantial agreement amongst reviewers for all items on the NOS (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.979, 95% CI 0.975–0.982).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the prospective studies obtained from the literature search

| Study, year | Country | Comparison groups | Number of patients | % Staged | Age (range), years | % female | NOS Quality Index | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hutchinson, 2006 | Australia | Simultaneous | 563 | 22.0 | 66.0 | 48.3 | 6 | – No significant difference in complication rates between SBTKA (26.3% of patients) and StBTKA (24.0% of patients) (p = 0.611) |

| Staged — 2 to 120 months | ||||||||

| Stanley, 1990 | UK | Simultaneous | 50 | 36.0 | 60.0 (32–77) | 76.0 | 6 | – No intra-operative complications in both treatment groups. |

| Staged — NR |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 18 non-randomized trials included in the meta-analysis

| Study, year | Country | Comparison groups | Number of patients | % staged | Age (range), years | % female | NOS Quality Index | Outcomes reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brotherton et al., 1986 [3] | USA | • Simultaneous | 47 | 61.7 | 62.8 | NR | 6 | ▪ DVT |

| • Staged — 9.2 months | ||||||||

| Forster et al., 2006 [6] | Australia | • Simultaneous | 102 | 72.5 | 66.0 (41–79) | 52.0 | 5 | ▪ RR |

| • Staged — 1 week to 68 months | ||||||||

| Gill et al., 2003 [7] | USA | • Simultaneous | 400 | 75.5 | 70.0 (19–93) | 59.3 | 7 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 3 months | ||||||||

| Ivory et al., 1993 [15] | UK | • Simultaneous | 93 | 15.1 | 68.2 (43–91) | 62.4 | 5 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 6 weeks to 6 months | ▪ IR | |||||||

| Jankiewicz et al., 1994 [16] | USA | • Simultaneous | 155 | 36.1 | 70 | 69.0 | 5 | ▪ PE |

| • Staged — within 9 months | ||||||||

| Liu and Chen, 1998 [19] | Taiwan | • Simultaneous | 88 | 27.3 | 67.7 (44–79) | 96.6 | 6 | ▪ DVT |

| • Staged — 7.4 days (5–11) | ▪ CC | |||||||

| ▪ IR | ||||||||

| Mangaleshkar et al., 2001 [20] | UK | • Simultaneous | 88 | 38.6 | 72.4 (36–90) | 61.4 | 6 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 5.2 months | ||||||||

| McLaughlin and Fisher, 1985 [21] | USA | • Simultaneous | 68 | 67.6 | 69.3 | 72.1 | 6 | ▪ DVT |

| • Staged — 17 days to 8 months | ▪ CC | |||||||

| ▪ IR | ||||||||

| ▪ RR | ||||||||

| Memtsoudis et al., 2009 [22] | USA | • Simultaneous | 33,662 | 25.2 | 66.1 | 58.7 | 8 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 3.59 days | ▪ PE | |||||||

| ▪ DVT | ||||||||

| ▪ CC | ||||||||

| Minter and Dorr, 1995 [23] | USA | • Simultaneous | 64 | 64.1 | 66 | 43.8 | 5 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — NR | ▪ PE | |||||||

| ▪ DVT | ||||||||

| Morrey et al., 1987 [24] | USA | • Simultaneous | 376 | 61.4 | 62.6 (22–88) | 66.2 | 5 | ▪ PE |

| • Staged — same hospitalizations and separate hospitalizations | ▪ RR | |||||||

| Ritter et al., 1997 [29] | USA | • Simultaneous | 63,030 | 79.5 | 73.2 | 65.8 | 6 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 6 weeks to 1 year | ||||||||

| Ritter et al., 2003 [28] | USA | • Simultaneous | 2202 | 6.9 | 69.9 | 57.3 | 6 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 1.4 ± 0.8 years | ▪ PE | |||||||

| ▪ CC | ||||||||

| ▪ IR | ||||||||

| Sliva et al., 2005 [30] | USA | • Simultaneous | 332 | 92.2 | 65.0 (35–90) | 63.9 | 6 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 1 hospitalization to 70.5 weeks | ||||||||

| Soudry et al., 1985 [31] | USA | • Simultaneous | 74 | 24.3 | 68.8 (38–85) | 70.3 | 4 | ▪ PE |

| • Staged — 29 days (1 week to 5 months) | ▪ CC | |||||||

| Stefansdottir et al., 1987 [33] | Sweden | • Simultaneous | 4571 | 75.1 | 80.0 (67–89) | NR | 6 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 1 to 2 years | ||||||||

| Walmsley et al., 2006 [34] | UK | • Simultaneous | 2622 | 68.5 | NR | NR | 5 | ▪ Mortality |

| • Staged — 1 to 5 years | ||||||||

| Yoon et al., 2010 [36] | South Korea | • Simultaneous | 238 | 50.0 | 70.0 (34–83) | 94.1 | 6 | ▪ IR |

| • Staged — 12 months (1–48 months) |

The “Outcomes reported” column only lists information used in the individual forest plots

NOS New Castle–Ottawa Scale, NR not reported, PE pulmonary embolism, DVT deep vein thrombosis, CC cardiac complications, IR infection rates, RR revision rates

The incidence of mortality suggests that staged bilateral procedures have a significantly lower mortality rate than simultaneous procedures. Information about mortality in simultaneous and staged groups was abstracted from 15 studies [6, 7, 15, 16, 19–23, 28–30, 33, 34, 36]. Four studies [16, 19, 21, 23] reported zero in-hospital mortality events post surgery for both comparison groups and one study [6] reported zero mortality events 30 days after surgery for both groups. Lastly, one study reported mortality at 15 days [15] and another reported at 60 days [30]. As a result, these studies were not included in the pooled estimate as no other studies reported data at these time points. The risk ratios amongst individual studies ranged from 0.94 to 9.18. Mortality rates over the first year ranged from 0.31% during in-hospital stay to 3.41% at 1 year after surgery for the SBTKA procedure. Mortality rates for the StBTKA procedure ranged from 0.27% during in-hospital stay to 2.02% at 1 year after surgery. The incidence of mortality in both groups was categorized into four subgroups (Fig. 2). The results of the analysis indicate that the choice of procedure (SBTKA or StBTKA) did not significantly influence in-hospital mortality rates (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.74–1.88, p = 0.48, I2 = 0%, n = 33,814 patients). However, the results at 30 days (RR 3.67, 95% CI 1.68–8.02, p = 0.001, I2 = 59%, n = 67,691 patients), 3 months (RR 2.45, 95% CI 2.15–2.79, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, n = 66,142 patients) and 1 year (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.66–2.06, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%, n = 65,322 patients) suggest that staged bilateral procedures have a significantly lower mortality rate than simultaneous procedures. The heterogeneity was higher than the pre-defined 25% cut-off when both groups were combined and this supported conducting sub-group analyses. It is important to note that there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in year of publication and mortality rate between the two groups at all time points. The prospective study that was excluded from this review measured peri-operative mortality rates also found no significant difference between the two groups [14].

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis forest plot on non-randomized trials comparing mortality rates amongst simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty procedures.

The prevalence of the peri-operative complications in the pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis and cardiac complications groups were relatively similar across both treatment arms. Eight studies provided information about the incidence of pulmonary embolism in both knee replacement groups [19, 21–24, 28, 30] during the peri-operative period. Five studies provided information about the incidence of deep vein thrombosis [3, 19, 21–23] and five studies provided information about the prevalence of cardiac complications in both patient groups [19, 21, 22, 28, 31]. Two studies [19, 21] reported zero pulmonary embolism events following simultaneous and staged BTKA. The risk ratios amongst individual studies varied from 0.64 to 4.78 (95% CI 0.06–45.51) for pulmonary embolism, 0.35 to 1.22 (95% CI 0.01–12.26) for deep vein thrombosis and 0.07 to 1.08 (95% CI 0.00–16.08) for cardiac complications. This was also found to be consistent with the excluded prospective study [14]. Approximately 0.91% of patients in the simultaneous treatment arm and 0.79% of patients in the staged treatment arm experienced an episode of pulmonary embolism. Deep vein thrombosis rates were also similar amongst both groups, affecting 1.47% of patients in the simultaneous arm and 1.30% of patients in the staged arm. Lastly, cardiac complication rates were similar amongst both groups as well, affecting 1.67% of patients in the simultaneous arm and 1.60% of patients in the staged arm.

Analysis of the results (Fig. 3) across studies illustrates no increased risk of in-hospital pulmonary embolism following simultaneous or staged BTKA procedures (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.90–1.53, p = 0.23, I2 = 0%, n = 36,533 patients). Furthermore, there was no increased risk of in-hospital deep vein thrombosis (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.44–1.80, p = 0.75, I2 = 11%, n = 33,929 patients) or in-hospital cardiac complications (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.28–1.71, p = 0.43, I2 = 37%, n = 36,094 patients) in either treatment arm. The heterogeneity in the cardiac complications group and the deep vein thrombosis group can be explained by publication year of the study. Studies published before 2000 report a lower risk of cardiac complications (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03–0.68, p = 0.01, I2 = 0%, n = 230 patients) in the simultaneous bilateral group and studies published after the year 2000 report no difference in either group (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.89–1.31, p = 0.41, I2 = 0%, n = 35,864 patients). Studies published before the year 2000 show a trend of lower deep vein thrombosis events in the simultaneous group; however this result is not statistically significant (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.06–1.12, p = 0.07, I2 = 0%, n = 267 patients). The study published after the year 2000 reports no difference in deep vein thrombosis events in either surgical procedure (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.98–1.52, p = 0.23, n = 33,662 patients). The statistical test of interaction revealed a significant difference between these two subgroups (z = −2.10, p = 0.02) which validates the publication date as a source of heterogeneity for deep vein thrombosis events.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis forest plot on non-randomized trials comparing peri-operative complication rates amongst simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty procedures.

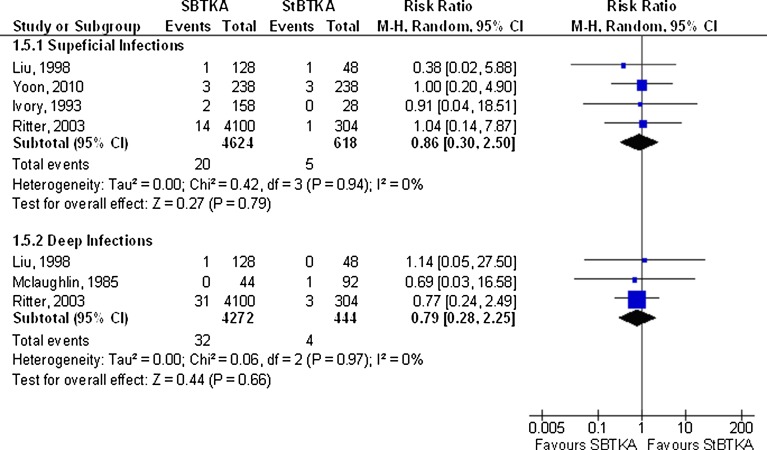

The incidence of peri-operative infection events in the superficial and deep infection subgroups was higher in the staged treatment arm; however, this finding was not statistically significant (Fig. 4). Peri-operative Infection rates were divided into two primary subgroups; superficial knee infections and deep knee infections. Six studies [15, 16, 19, 21, 28, 36] provided information about the incidence superficial knee infection and 5 studies [4, 9, 19, 28, 36] provided information about deep infection. Two studies [16, 36] reported zero superficial and deep infection events following simultaneous and staged BTKA. The risk ratios amongst individual studies varied from 0.38 to 1.04 for superficial infection and 0.69 to 1.14 for deep infection. Approximately 0.43% of patients in the simultaneous treatment arm and 0.81% of patients in the staged treatment arm had a superficial infection event. Deep knee infection rates were also similar amongst both groups, affecting 0.75% of patients in the simultaneous arm and 0.90% of patients in the staged arm. Analysis of the results across studies illustrates no increased risk of superficial knee infection following simultaneous or staged BTKA procedures (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.30–2.50, p = 0.79, I2 = 0%, n = 5,242 patients). It should be noted that when data was stratified according to year of publication, the pooled results from the two studies [15, 19] published before the year 2000 trended towards a higher rate of superficial infections when using staged BTKA; however it was still non-significant (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.07–4.28, p = 0.58, I2 = 0%, n = 362). The two studies [28, 36] published after the year 2000 reported virtually no difference between the two groups (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.29–3.54, p = 0.98, I2 = 0%, n = 4880). This difference may have been due to the variety of changes such as those in surgical procedure and perioperative care which may have decreased the rate of superficial infections. The risk ratio calculated for the risk of a deep infection event in either comparison group was non-significant (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.28–2.25, p = 0.97, I2 = 0% n = 4716 patients). This is once again consistent with the results from the excluded prospective study [14]. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in either subgroup. No differences were observed when data was stratified according to time of publication.

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis forest plot on non-randomized trials comparing peri-operative infection rates amongst simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty procedures.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to provide insight about the benefits and risks associated with surgical techniques used for the treatment of bilateral degenerative knee conditions. This review focuses on the incidence of mortality, peri-operative complications, and infection rates following simultaneous and staged bilateral TKA. The results of our review suggest a decreased risk of mortality following staged procedures at 30 days, 3 months and 1 year after surgery. However, the results suggest that the two procedures are comparable with regards to complication and infection rates. More specifically, there significant differences were not observed in cardiac complications, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis and superficial/deep infection.

The findings of our study indicate a reduced risk of mortality following staged procedures. The higher risk of mortality in the simultaneous group may be due to the invasive nature of the procedure when compared to staged surgery (two knees simultaneously versus one knee at a time). While the analysis of mortality rates displays a clear advantage for staged procedures, it is important to remember that patients categorized in the staged group must survive the first operation in order to receive the next one. In addition, several other patient related factors associated with age may affect the mortality rate at 1 year. Second, when staged procedures are performed over longer periods of time, patients may die in between both procedures. These patients are considered unilateral TKA patients in a majority of analyses which may not be true as they may display bilateral symptoms. Furthermore, surgeons may decide not to perform the second staged procedure on patients who experienced significant complications following the first procedure. This adds additional bias to the results and limits the validity of the findings.

Our findings in this review must be interpreted with caution due to the methodological limitations of this study. The results of this review are based upon the pooling of results across various retrospective studies. Results were pooled across similar study subgroups when possible to ensure homogeneity across study designs. The pooling of studies also allows for an increased sample size and higher statistical power when determining effect size. Limitations of this study include the use of retrospective studies in the meta-analysis. Three of these studies [22, 29, 33] include registry data (Swedish Arthroplasty Registry, Medicare population) with large patient populations, which significantly increase their weight in the pooled results. Thus, the pooled risk ratio calculated in the different subgroups may be driven by the results of a select few trials. Moreover, retrospective studies are prone to publication, attrition and selection bias which can affect the validity of the results. The use of unadjusted results in the meta-analysis affects the comparisons made across different studies due to the lack of information available about pre-operative and post-operative status for patients in each treatment arm. Variations in surgical technique, pre-operative and post-operative care protocols across different institutions may also increase confounding across the pooled results. Furthermore, most of the studies included in this review performed staged procedures across a variety of intervals, ranging from 3.6 days to 5.9 years. The staging of procedures over these intervals may lead to a variety of confounding factors, such as increased patient age, level of recovery from the first procedure and differences in surgical technique. Additionally, a majority of studies did not specify differences between sequential bilateral total knee arthroplasty and simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty performed under one anaesthetic. Lastly, this review only accounts for major complications that were consistently reported in the literature. Further research must be conducted to evaluate minor complications amongst simultaneous and staged procedures.

A recent meta-analysis conducted by Restrepo and colleagues [27] measured outcomes similar to the ones reported in this study. The results of their review suggest a higher risk of cardiac events and mortality following simultaneous bilateral total knee replacement when compared to unilateral and staged bilateral total knee replacement. The study also reports no increased risk of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in either comparison group. The results of our study strengthen the conclusions of Restrepo and colleagues [27] by introducing an additional 41,432 patients to the mortality estimate and 33,939 patients to the peri-operative complications estimate, which increases the sample size and allows for the calculation of a more robust effect size. Our study also adds to the results of Restrepo’s meta-analysis by examining infection rates and revision surgeries amongst both comparison groups.

Another recent meta-analysis conducted by Hu and colleagues also found similar results to our findings [13]. They reported that 30-day mortality and rates of neurological complications was significantly in higher in patients that received simultaneous total knee arthroplasty. In addition, similar to our findings, they found no significant difference in complication rates between the two groups.

In conclusion the findings of our study suggest that SBTKA procedures are associated with a higher risk of mortality at 30 days, 3 months and 1 year after surgery when compared to StBTKA. However, there are no significant differences between the two groups in regards to in-hospital mortality. The risk of peri-operative complications including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, cardiac complications and infection rates is similar between simultaneous and staged groups. The results of the review must be interpreted with great caution due to the use of non-randomized retrospective studies in the primary meta-analysis and due to the limited number of studies included in each outcome. The results of this review bring to light the significant lack of evidence on this important topic. Further research must be conducted − in the form of a randomized clinical trial—to evaluate the outcomes mentioned in this review. Additionally, studies must also be conducted to determine the ideal range for performing a staged procedure (i.e., peri-operative stay or staged at 8 months). Information about quality of life and patient satisfaction following surgery may provide insight into the patient’s experience with these two common knee replacement procedures. Comparing this information with resource implications and cost-analysis data will allow patients, surgeons and health care professionals to make informed decisions when weighing the benefits and risks of simultaneous and staged bilateral TKA.

Conflict-of-Interest:

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. One or more of the authors has or will received payments from a commercial entity that may be perceived as a potential conflict of interest. One or more of the authors’ institution has or will received payments from a commercial entity that may be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

Human/Animal Rights:

Not applicable

Informed Consent:

Not applicable

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: Therapeutic Study Level IV. See levels of evidence for a complete description.

References

- 1.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326:219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett J, Baron JA, Losina E, Wright J, Mahomed NN, Katz JN. Bilateral total knee replacement: staging and pulmonary embolism. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2146–2151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotherton SL, Roberson JR, de Andrade JR, Fleming LL. Staged versus simultaneous bilateral total knee replacement. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1(4):221–228. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(86)80011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett RSJ, MacDonald SJ. Complications in bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 2003;14(4):245–262. doi: 10.1053/j.sart.2003.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster MC, Bauze AJ, Bailie AG, Falworth MS, Oakeshott RD. A retrospective comparative study of bilateral total knee replacement staged at a one-week interval. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(8):1006–1010. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B8.17862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill GS, Mills D, Joshi AB. Mortality following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(3):432–435. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gradillas EL, Volz RG. Bilateral total knee replacement under one anesthetic. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;140:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardaker WT, Ogden WS, Musgrave RE, Goldner JL. Simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(2):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris WH, Sledge CB. Total hip and total knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(11):725–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009133231106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooper GJ, Hooper NM, Rothwell AG, Hobbs T. Bilateral total joint arthroplasty: the early results from the New Zealand national joint registry. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(8):1174–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J, Yuan L, Zheng L, Xiang L, Xiaodong Q, Fan W. Mortality and morbidity associated with simultaneous bilateral or staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(9):1291–1298. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchinson JR, Parish EN, Cross MJ. A comparison of bilateral uncemented total knee arthroplasty: simultaneous or staged? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(1):40–43. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivory JP, Simpson AH, Toogood GJ, McLardy-Smith PD, Goodfellow JW. Bilateral knee replacements: simultaneous or staged? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1993;38(2):105–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankiewicz JJ, Sculco TP, Ranawat CS, Behr C, Tarrentino S. One-stage versus 2-stage bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;309:94–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1487–1497. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang MH, Cullen KE, Larson MG. Cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):937–943. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu TK, Chen SH. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty in a single procedure. Int Orthop. 1998;22(6):390–393. doi: 10.1007/s002640050284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangaleshkar SR, Prasad PS, Chugh S, Thomas AP. Staged bilateral total knee replacement — a safer approach in older patients. Knee. 2001;8(3):207–211. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(01)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin TP, Fisher RL. Bilateral total knee arthroplasties. Comparison of simultaneous (two-team), sequential, and staged knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;199:220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Memtsoudis SG, Ma Y, González Della Valle A, Mazumdar M, Gaber-Baylis LK, MacKenzie CR, Sculco TP. Perioperative outcomes after unilateral and bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(6):1206–1216. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bfab7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minter JE, Dorr LD. Indications for bilateral total knee replacement. Contemp Orthop. 1995;31(2):108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrey BF, Adams RA, Ilstrup DM, Bryan RS. Complications and mortality associated with bilateral or unilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(4):484–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray A, Brenkel I. Bilateral total knee replacement. Current Orthop. 2003;17(4):308–312. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0890(03)00048-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil N, Wakankar H. Morbidity and mortality of simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2008;31(8):780–789. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080801-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Dietrich T, Einhorn TA. Safety of simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1220–1226. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritter MA, Harty LD, Davis KE, Meding JB, Berend M. Simultaneous bilateral, staged bilateral, and unilateral total knee arthroplasty. A survival analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1532–1537. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritter M, Mamlin LA, Melfi CA, Katz BP, Freund DA, Arthur DS. Outcome implications for the timing of bilateral total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:99–105. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199712000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sliva CD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Taylor SG. Staggered bilateral total knee arthroplasty performed four to seven days apart during a single hospitalization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(3):508–513. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soudry M, Binazzi R, Insall JN, Nordstrom TJ, Pellicci PM, Goulet JA. Successive bilateral total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(4):573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanley D, Stockley I, Getty CJ. Simultaneous or staged bilateral total knee replacements in rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72(5):772–774. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B5.2211753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefánsdóttir A, Lidgren L, Robertsson O. Higher early mortality with simultaneous rather than staged bilateral TKAs: results from the Swedish knee arthroplasty register. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):3066–3070. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walmsley P, Murray A, Brenkel IJ. The practice of bilateral, simultaneous total knee replacement in Scotland over the last decade, data from the Scottish arthroplasty project. Knee. 2003;13(2):102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa, ON. Available from www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed October 2010.

- 36.Yoon HS, Han CD, Yang IH. Comparison of simultaneous bilateral and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty in terms of perioperative complications. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]