Abstract

The behavior of psychopathic individuals is thought to reflect a core fear deficit that prevents these individuals from appreciating the consequences of their choices and actions. However, growing evidence suggests that psychopathy-related emotion deficits are moderated by attention and, thus, may not reflect a reduced capacity for emotion responding. The present study attempts to reconcile this attention perspective with one of the most cited findings in psychopathy, which reports emotion-modulated startle deficits among psychopathic individuals during picture viewing. In this study, we evaluate the potential effects of a putative attention bottleneck on the emotion processing of psychopathic offenders during picture viewing by manipulating picture familiarity and examining emotion-modulated startle and late positive potential (LPP). As predicted, psychopathic individuals displayed the classic deficit in emotion-modulated startle during novel pictures, but they showed no deficit in emotion-modulated startle during familiar pictures. Conversely, results for LPP responses revealed psychopathy-related differences during familiar pictures and no psychopathy-related differences during novel pictures. Important differences related to the two Factors of psychopathy are also discussed. Overall, the results of this study not only highlight the differential importance of perceptual load on emotion processing in psychopathy, but also raise interesting questions about the varied effects of attention on psychopathy-related emotion deficits.

Keywords: Picture-viewing, Emotion-Modulated Startle, Late Positive Potential, Psychopathy, PCL-R Factors, Attention Bottleneck

Cognitive and affective neuroscientists continue to debate the extent to which emotion processing occurs automatically, that is without the influence of top-down processes (e.g., attention), or is in fact dependent upon the availability of attention. This question has fundamental importance for the conceptualization of a number of clinical disorders (e.g. anxiety, substance dependence, psychopathy). With regard to psychopathy, some models propose that psychopathic individuals are characterized by an innate deficit in emotion processing (Lykken, 1957; Patrick, 2007; Sylvers, Brennan & Lilienfeld, 2011), whereas others posit an attention abnormality that curtails the processing of emotion and other important information (Forth & Hare, 1989; Newman & Baskin-Sommers, 2011; Patterson & Newman, 1993). In order for theory and treatment development in the field of psychopathy to advance, it is crucial to reconcile the fundamental differences between these models.

Historically, the behavior of psychopathic individuals is thought to reflect a core fear deficit that prevents these individuals from appreciating the consequences of their choices and actions (Lykken, 1957; Patrick, 2007). Empirically, the most cited and arguably strongest evidence for this innate fear deficit comes from studies that assess emotion-modulated startle using the picture-viewing paradigm. In contrast to non-psychopathic individuals, who display startle potentiation to noise probes while viewing unpleasant pictures and startle inhibition while viewing pleasant pictures, the startle potentiation to unpleasant pictures appears to be lacking in psychopathic participants (Levenston, Patrick, Bradley & Lang, 2000; Patrick, Bradley & Lang, 1993; Patrick, 1994). This effect is particularly evident in individuals high on the interpersonal-affective traits of psychopathy (i.e., Factor1; Patrick, 1994; Vaidyanathan, Hall, Patrick & Bernat, 2011). Such findings are generally interpreted as evidence that psychopathic individuals have a fundamental fear deficit (i.e., deficit in defense system reactivity) that undermines their reaction to threatening/unpleasant images in an experimental context (Lykken, 1995; Patrick, 1994) and, by extension, their sensitivity to the affect of other individuals, yielding a callous and aggressive interpersonal style (Patrick, 2007).

Although attributing the emotion-modulated startle deficit of psychopathic individuals to a fundamental emotion deficit may seem intuitive, such a conclusion largely overlooks the known impact of attention on emotion reactivity, particularly measured during picture-viewing paradigms (Bradley, Codispoti & Lang, 2006; Levenston et al., 2000). While startle potentiation is an index of defensive and appetitive motivation, it also reflects the engagement of sensory processes and attention allocation (Bradley et al., 2006; Filion et al., 1993). As noted by Levenston and colleagues (2000) an alternative explanation for the failure of psychopathic individuals to show startle potentiation is not only related to a deficit in emotion processing, but more specifically an abnormality in the normal interplay between attentional engagement and affective processing during the viewing of unpleasant scenes. This conclusion is consistent with other evidence that demonstrates psychopathy-related emotion deficits are moderated by attention (Baskin-Sommers, Curtin & Newman, 2011; Newman, Curtin, Bertsch & Baskin-Sommers, 2010). While previous research on the psychopathy-related emotion-modulated startle deficit has noted the importance of attention, little has been done to integrate prominent attention models of psychopathy with this specific deficit.

According to Newman and colleagues, an early attention bottleneck plays a critical role in moderating the affective deficits associated with psychopathy. Based on models of selective attention, it is proposed that once an early attention bottleneck is established, it blocks the processing of secondary (i.e., peripheral) information that is not goal-relevant. This filter can affect processing at the level of the visual cortex and perception (Hillyard, Vogel & Luck, 1998; Kastner & Ungerleider, 2000). While this attention bottleneck may allow psychopathic individuals to be more effective at filtering out distraction and focusing on personal goals, it may also leave them vulnerable to over-allocating attention to goal-relevant cues at the expense of processing important context-relevant information (Zeier, Maxwell & Newman, 2009; see also Hare, 1978). For example, such an inflexible focus on personal goals may underlie the self-centered, callous traits associated with psychopathy (i.e., Factor1 traits). More generally, a deficit in the ability to process multiple aspects of a situation may leave psychopathic individuals oblivious to the potentially devastating consequences of their behavior.

To date, tests of the attention bottleneck model manipulate attentional focus and find that the emotion-related deficits associated with psychopathy appear and disappear according to whether the emotion cues are goal-relevant (i.e., primary) or peripheral to their goal-directed focus of attention (Baskin-Sommers et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2010). Yet, such findings appear to be at odds with the fact that psychopathic participants display reliable deficits in emotion-modulated startle in the picture-viewing paradigm even though participants are instructed to focus on the picture content (i.e., it is their primary focus of attention; Levenston et al., 2000; Patrick et al., 1993; Patrick, 1994; Vaidyanathan, et al., 2011).

Much of the difficulty in comparing the attentional and low-fear perspectives relates to the use of different methodologies and paradigms. Recent evidence that psychopathic and nonpsychopathic individuals display comparable fear when instructed to focus directly on threat cues was obtained using perceptually simple boxes and letter stimuli. As such, the minimal perceptual demands in the emotion-focused conditions of these studies (e.g., the color of a letter or box) may not have disrupted affective processing in psychopathic individuals. Conversely, picture stimuli place considerable demands on perception (Bradley, Hamby, Low & Lang, 2007). In light of this evidence, we speculated that the attention bottleneck in psychopathy would interact with the perceptual demands associated with picture processing and differentially impact the affective processing of psychopathic individuals.

To the extent that a psychopathy-related attention bottleneck fosters serial processing and constrains the simultaneous processing of picture elements, it would make processing the pictures less efficient and disrupt the fluent processing of complex pictures. Further, this disruption in processing might attenuate the emotion response. More specifically, it may be that at the time that affect is typically assessed psychopathic individuals have not yet integrated the components of the picture. In fact, previous research suggests that the psychopathy-related startle deficit is time-limited; that is given enough time to process a picture psychopathic and nonpsychopathic individuals show comparable startle potentiation (Levenston et al., 2000; Sutton et al., 2002). Combined with other evidence for an attention bottleneck, these findings suggest that it should be possible to alleviate the effects of psychopathic individual’s putative bottleneck by manipulating the processing demands during picture processing. One way to evaluate this proposal would be to use an experimental manipulation that alters the perceptual load.

In this vein, Bradley and colleagues examined the effect of familiarity, as a means of reducing perceptual demands associated with picture-viewing (Bradley, Lang & Cuthbert, 1993; Codispoti, Ferrari, & Bradley, 2006; Ferrari, Bradley, Codispoti & Lang, 2011). Generally speaking, familiarity (repeated exposure) did not appear to reduce emotion-modulated startle, but did alter online information processing demands as measured by event-related potentials. The fact that familiarity reduces perceptual load without impacting affective responses provides an elegant way to examine the importance of processing load, and indirectly the attention bottleneck, on psychopathy-related deficits in picture-viewing paradigms.

In the present study, we manipulate the familiarity of pictures to assess the extent to which the demands of processing novel versus familiar pictures moderate psychopathy-related differences in emotion-modulated startle magnitude. Consistent with previous studies, we expect that psychopathic individuals will show a significant emotion-modulated startle deficit when viewing novel pictures (i.e., reduced differentiation between unpleasant and pleasant pictures compared to individuals low on psychopathy). Conversely, assuming that familiarity reduces the perceptual demands associated with picture viewing, individuals high and low on psychopathy will display equivalent emotion-modulated startle while viewing familiar pictures.

Though our predictions are based primarily on understanding the balance between emotion-modulated startle and perceptual demand (i.e., familiarity manipulation), given the predominance of shallow affect in the phenotypic presentation of psychopathy, it may also be important to evaluate the depth of affective processing or, more specifically, the elaboration of affective information. According to Bradley, Hamby, Low and Lang (2007), it is possible to assess the extent to which a person perceives and directs attention to motivational relevance during picture viewing, regardless of picture-related differences in perceptual load, by measuring the late positive event-related potential (LPP). The LPP has an onset around 300 ms after picture presentation and is strongly modulated by the emotional intensity of a stimulus (e.g., greater LPP response to either a positively or negatively valenced stimulus than a neutral stimulus; Hajcak, MacNamara & Olvet, 2010). More specifically, LPP is thought to index affective elaboration (i.e., commitment of motivated attentional resources to the pictures and sustained elaboration of the picture content; Hajcak, et al., 2010). While many other psychophysiological measures of emotion processing, including skin conductance, heart rate, facial electromyography, and amygdala activation, habituate over time, the greater response of the LPP for affective compared to neutral pictures does not appear to habituate over repeated presentations of stimuli (Codispoti, Ferrari, & Bradley, 2006, 2007; Olofsson & Polich, 2007). The stability of this affective modulation of LPP is thought to reflect a variety of psychobiological processes that interact throughout the time course of this physiological reaction to affective information (Moratti, Saugar, & Strange, 2011).

Thus, in addition to assessing emotion-modulated startle, we measured LPP to evaluate the effects of perceptual load on affective elaboration in psychopathic individuals. Based on the assumption that an attention bottleneck would interfere with the ability of psychopathic individuals to elaborate on the affective significance of novel pictures, we predicted that emotion cues would produce smaller changes in LPP magnitude among psychopathic participants viewing novel pictures. However, to the extent that familiarity reduces perceptual load, we hypothesized that the LPP response of psychopathic individuals would be comparable to that of nonpsychopathic individuals (i.e., individuals high and low on psychopathy would display comparable potentiation of LPP to affective versus neutral picture).

In sum, this study aims to evaluate the potential effects of an attention bottleneck on the emotion processing of psychopathic offenders during picture viewing by manipulating picture familiarity and employing complementary measures of affective processing (i.e., emotion-modulated startle; LPP). Moreover, some researchers advocate parsing psychopathy into two components (i.e. Factor1: Interpersonal/Affective and Factor2: Impulsive/Antisocial) so that the unique correlates of these components can be identified (Patrick, 2007). Additionally, previous studies report a specific association between high Factor1 traits and the emotion-modulated startle deficit. Therefore, in addition to focusing on the impact of attention on emotion processing in psychopathy, we reexamine all predictions while focusing on the Factors associated with psychopathy. The predicted results would not only reconcile findings regarding psychopathy-related performance deficits on tasks involving emotion stimuli that are the primary focus of attention, but would also identify a fundamental and consequential information-processing deficit in psychopathy.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 136 male inmates from a maximum security prison in Southern Wisconsin. Participants were excluded if they were 46 years of age or older, had an estimated IQ score of less than 70 on the Shipley Institute of Living Scale (Zachary, 1986), had clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or psychosis NOS, or were currently using psychotropic medications.

Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 2003)

All participants were assessed for psychopathy using the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. This measure uses information gleaned from an interview and a review of institutional files to score the participant on the presence of 20 different items. A score of 0, 1, or 2, is given for each item according to the degree to which a characteristic is present. Thus, PCL-R total scores range from 0 to 40.

The reliability and validity of the PCL-R is well established (see Hare, 2003; Hare et al., 1990). In this study, reliability ratings were available for 16 randomly selected participants. The inter-rater reliability for PCL-R total scores, PCL-R Factor1 (Interpersonal/Affective), and PCL-R Factor2 (Impulsive/Antisocial) were .98, 97, and .99, respectively.

Experimental Task

Thirty-six pictures (12 unpleasant, 12 neutral, and 12 pleasant) were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS, Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008)1 for this experiment. The pleasant and unpleasant pictures differed in affective valence, but were well matched on arousal based on published norms. Neutral pictures were selected to represent the midpoint between pleasant and unpleasant valence but were lower in arousal as dictated by their neutral content (Mean Valence: 7.2 (unpleasant), 4.8 (neutral), 2.2 (pleasant); Mean Arousal: 6.2 (unpleasant), 2.6 (neutral), 6.6 (pleasant).

Six of these pictures (2 unpleasant, 2 neutral, and 2 pleasant) were randomly chosen to be presented repeatedly during a familiarization block at the start of the task. The specific pictures selected for this familiarization block were randomized across participants. These six pictures were displayed 10 times each for a total of 60 trials during the familiarization block. Each picture was presented for four seconds with one second between each trial during the familiarization block.

Following the familiarization block, participants completed an additional 60 trials of picture-viewing for the main task. Half of these trials involved repeated presentation of the 6 pictures that were previously presented in the familiarization block. Each of these familiar pictures was presented for an additional 5 trials. The other half of trials involved presentation of novel (i.e., not previously viewed) pictures. The remaining 30 pictures (10 unpleasant, 10 neutral, and 10 pleasant) from the set of 36 pictures were used for these trials. Each of these novel pictures was presented only once during the main task. Novel and familiar picture trials were intermixed during the main task. Pictures were presented for 4 seconds each with an average of 10 seconds between trials (range = 8 – 12).

During both the familiarization block and main task, participants were not asked to respond to the pictures. Following previous protocols, participants were instructed to view each picture for the entire time it was displayed and to ignore any noises (i.e., the startle probes, see below) heard over the headphones.

Physiological Recording and Data Reduction

Stimulus presentation and data collection were controlled by a PC-based Matlab script using the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997) and Neuroscan Synamps amplifiers and acquisition software (Compumedics, North Carolina). Offline data processing was conducted with the PhysBox plugin (Curtin, 2011) within the EEGLab toolbox (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) in Matlab.

Startle Response

The startle response was elicited by 50ms, 105db, white noise ‘startle’ probes that were presented during picture presentation. Eight probes were presented within each of the six conditions defined by the orthogonal crossing of picture emotion (unpleasant vs. neutral vs. pleasant) and familiarity (familiar vs. novel). Two probe times (2.3 and 3 seconds post picture onset) were used to reduce predictability of the probe.

The startle response was measured by recording electromyogram (EMG) activity from Ag-AgCl electrodes placed over the orbicularis oculi muscle under the right eye. The raw EMG was sampled at 2000Hz with a bandpass filter (30–500Hz; 24dB/octave roll-off). Offline processing included epoching (−50ms to 250ms surrounding probe onset), rectification and smoothing (4th order, 30Hz Butterworth lowpass filter), and baseline correction. Startle blink magnitude was scored as the peak response between 20–120 ms post-probe onset. Mean startle response was calculated across the 8 probes within each of the picture emotion X familiarly conditions described earlier.

Event Related Potentials (ERPs)

EEG was recorded from Ag-AgCl electrodes mounted in an elastic cap (Electro Cap International) and located at standard midline positions (Fz, FCz, Cz, and Pz) referenced to the left mastoid. Vertical eye-movement was measured with additional electrodes placed above and below the left eye. Electrode impedance for all channels was kept below 10 KΩ.

Offline processing included re-referencing to average mastoids, low pass filtering (2nd order, 30Hz Butterworth low pass filter), epoching (−500ms −1000ms epochs surrounding picture onset), baseline correction, artifact rejection (trials with voltages exceeding ±75microvolts were rejected). Average ERP waveforms were calculated across trials within the six picture emotion X familiarity conditions. Visual inspection confirmed that the LPP was maximal at the Pz scalp site. The measurement window for the LPP as centered on the maximum response in grand average waveforms across participants and conditions at Pz was between 376 – 576ms post picture onset.

Data Analysis

Each measure (startle response and LPP) was analyzed in separate general linear models with familiarity (2: familiar, novel) and emotion (3: pleasant, neutral, unpleasant) as within-subjects categorical factors and Psychopathy total score (mean-centered) as a between subject continuous factor. Given that both startle and LPP are commonly analyzed in terms of specific emotion contrasts (startle: pleasant versus unpleasant assesses emotion-modulated startle; LPP: pleasant/unpleasant versus neutral assesses the emotion modulation of LPP) planned orthogonal contrasts are reported for each measure. Specifically, effects involving emotion are examined with valence (unpleasant vs. pleasant) and affect (unpleasant/pleasant vs. neutral) contrasts. Where appropriate, unpleasant vs. neutral contrasts are also reported to facilitate comparisons with other tasks that compare threat to no-threat conditions (Baskin-Sommers, et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2010; Sadeh & Verona, 2012; Vaidyanathan et al., 2011). Analyses were also repeated using the Factor scores (both Factor1 and Factor2 simultaneously entered, as well as their interaction) instead of the Psychopathy total score. To protect against violations of the assumption of sphericity, Huynh–Feldt corrected p-values are reported.

Results

Psychopathy

Startle Response

Consistent with previous picture-viewing studies, there was a significant valence contrast, F(1,134)=91.15, p<.01, ηp2=.40, indicating that the startle response was greater during unpleasant versus pleasant pictures (i.e., emotion-modulated startle). There was also a main effect of familiarity with participants showing larger startle to the familiar pictures than to the novel pictures, F(1,134)=19.11, p<.01, ηp2=.12. The main effect of psychopathy was not significant, F(1,134)=.01, p=.94.

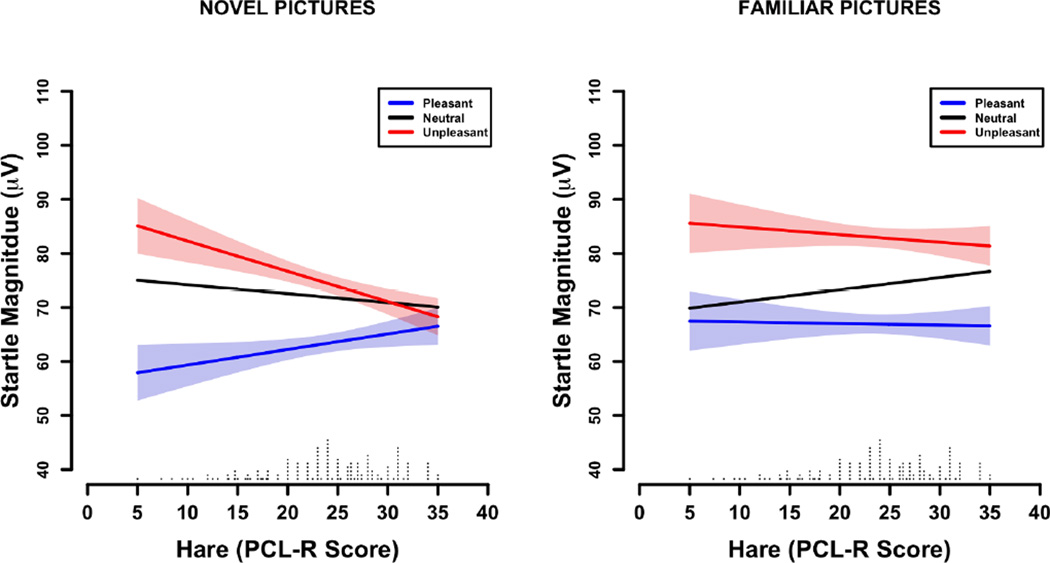

Critical to our a priori hypothesis, the valence contrast was moderated by psychopathy and familiarity (i.e., Psychopathy X Familiarly X valence contrast), F(1,134)=5.44, p=.02, ηp2=.04 (Figure 1)2. To unpack this significant three-way interaction, we examined the simple two-way interactions separately for novel and familiar trials.

Figure 1.

Emotion-modulated startle as a function of psychopathy. Results are shown for the novel trials (left side) and familiar trials (right side). Psychopathy scores were estimated from Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (2003). The frequency of each psychopathy score is indicated above the x-axis. Error bands represent the standard error of the valence contrast (i.e., pleasant versus unpleasant).

As predicted, there was a significant psychopathy X valence interaction for novel trials, F(1,134)=10.48, p<.01, ηp2=.10, indicating that the magnitude of the valence contrast during novel pictures decreased as psychopathy scores increased. In contrast, the psychopathy × valence interaction was not significant for familiar trials, F(1,134)=.16, p = .69, indicating that the magnitude of the valence contrast during familiar pictures was consistent across the range of psychopathy scores. Overall, these results suggest that psychopathic individuals displayed deficient emotion-modulated startle during novel pictures, but that both individuals high and low on psychopathy displayed comparable emotion-modulated startle when the pictures were familiar3.

LPP Response4

The affect contrast was significant, F(1,100)=289.37, p<.01, ηp2=.74, with LPP larger during pleasant and unpleasant vs. neutral pictures. Additionally, there was a main effect of familiarity with participants showing increased LPP to the familiar pictures than to the novel pictures, F(1,100)=82.85, p<.01, ηp2=.45. The main effect of psychopathy was not significant, F(1,100)=2.13, p=.15.

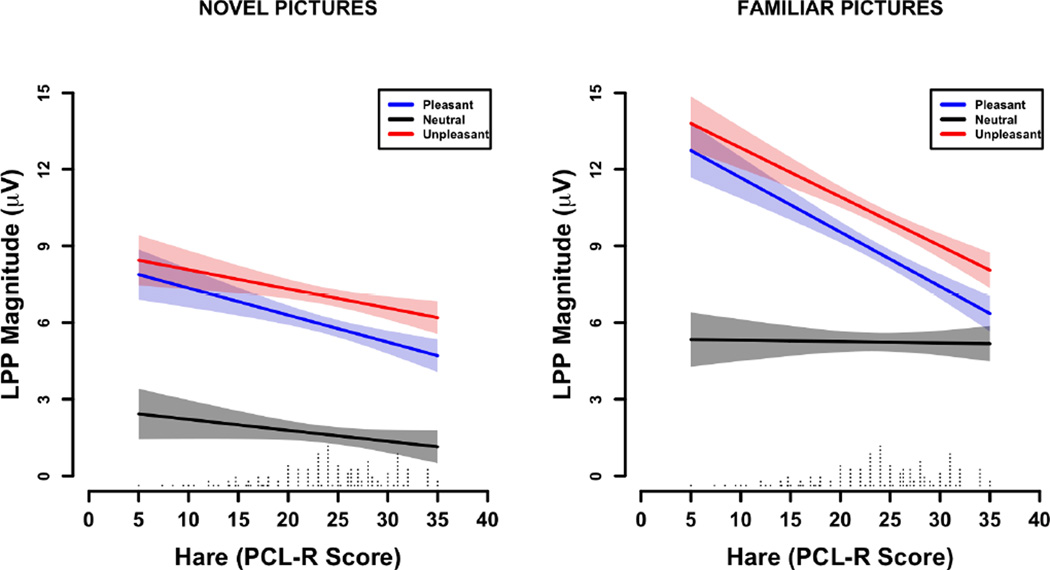

The affect contrast was moderated by psychopathy and familiarity (i.e., Psychopathy X Familiarity X affect contrast interaction), F (1,100)=5.39, p=.02, ηp2=.06, (Figure 2). To unpack this significant three-way interaction we examined the simple two-way interactions separately for the novel and familiar trials.

Figure 2.

Late positive potential (LPP) as a function of psychopathy. Results are shown for the novel trials (left side) and familiar trials (right side). Psychopathy scores were estimated from Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (2003). The frequency of each psychopathy score is indicated above the x-axis. Error bands represent the standard error of the affect contrast (pleasant/unpleasant versus neutral).

For novel trials, the Psychopathy X affect contrast interaction was not significant F(1,100)=.93, p=.34, indicating that the magnitude of the pleasant/unpleasant vs. neutral contrast for LPP was consistent across the range of psychopathy scores. However, there was a significant Psychopathy X affect contrast interaction for familiar trials, F(1,100)=13.79, p<.01, ηp2=.12. That is, the magnitude of the pleasant/unpleasant vs. neutral contrast for LPP (i.e., increased LPP during affective vs. neutral pictures) decreased with increasing psychopathy scores. Thus, contrary to a priori predictions, psychopathy-related differences in the effect of affect on LPP were associated with familiar rather than novel picture viewing.

Factors of Psychopathy

Supplemental analyses were conducted with the Factors of psychopathy rather than the PCL-R total scores.

Startle Response

In contrast to earlier results for psychopathy total scores, the three-way interaction, Factor1 X Familiarity × valence, was not significant, F(1,132)=.30, p=.58. Moreover, none of the two-way interaction contrasts were significantly related to Factor1. Results for Factor2 generally followed results reported earlier for psychopathy total scores. The Factor2 X Familiarity X valence contrast interaction was significant, F(1,132)=3.98, p=.05, ηp2=.03. During novel pictures, the magnitude of valence contrast decreased as Factor2 scores increased, F(1,132)=5.48, p=.02, ηp2=.04. However, there was no significant Factor2 X valence interaction during familiar pictures, F(1,132)=.003, p=.95.

Given the importance of the putative fear deficit in the field of psychopathy, some researchers compare reactivity to unpleasant vs. neutral slides because it provides a more specific test of fear-related processing in psychopathy (Sadeh & Verona, 2012; Vaidyanathan et al., 2011). Moreover, there is strong evidence that the deficit in startle potentiation for unpleasant versus neutral slides is specific to Factor1 of psychopathy (Vaidyanathan et al., 2011). Thus, supplemental analyses examined the unpleasant vs. neutral contrasts. In the novel trials, there was a significant Factor1 × unpleasant vs. neutral interaction, F(1,132)=4.71, p=.03, ηp2=.03, with the magnitude of the unpleasant vs. neutral contrast decreasing with increasing scores on Factor1. However, as with the analysis of psychopathy total scores, there was no evidence that this pattern was present in the familiar condition, F(1,132)=.58, p=.45. Comparable analyses employing Factor2 scores revealed no significant differences [Novel: F(1,132)=.00, p=.99; Familiar: F(1,132)=1.11, p=.30], suggesting that their deficit in startle reactivity (i.e., emotion-modulated startle reported in the primary analysis) is related to emotion processing more generally (i.e., including pleasant pictures) rather than being specific to low-fear (unpleasant pictures).

LPP Response

No significant effects involving Factor1 were observed for LPP. The Factor2 X Familiarity X affect contrast interaction was marginal, F(1,98)=3.34, p=.07, ηp2=.03. The Factor2 X affect interaction was not significant for novel trials, F(1,98)=.01, p=.93. In contrast, a significant Factor2 X affect contrast was observed for familiar trials, F(1,98)=5.25, p=.02, ηp2=.05. This indicated that the magnitude of the pleasant/unpleasant vs. neutral contrast decreased as Factor2 scores increased selectively during familiar trials.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of perceptual load on the psychopathy-related emotion deficit in picture-viewing paradigms. Our primary hypotheses centered on the psychopathy-related deficit in emotion-modulated startle. However, to advance our understanding of the complex cognitive-emotional interactions operating in psychopathy, we also examined LPP as a measure of affective elaboration. Additionally, we conducted supplementary statistical analyses using the two major factors of the PCL-R, rather than psychopathy total scores, to clarify the unique contribution of each factor to the cognitive-affective abnormality in psychopathy.

Psychopathy

The psychopathy-related deficit in emotion-modulated startle is one of the most reliable and important findings in the field of psychopathy (Patrick, 2007). Moreover, such deficits may undermine the formation of mental representations for emotion-eliciting stimuli and, ultimately, the elaboration of affective information in psychopathic individuals (Blair, 2008). The present results indicate that these deficits in emotion processing are moderated by contextual demands on information processing. More specifically, they demonstrate that perceptual load differentially impacts the emotion-modulated startle and LPP responses of psychopathic individuals during the viewing of emotionally evocative pictures.

Emotion-Modulated Startle

Newman and Baskin-Sommers (2011) proposed that psychopathy is associated with an early attention bottleneck that impedes information processing. Although previous research focused on the consequences of this bottleneck for the processing of peripheral and/or perceptually simple stimuli, such a bottleneck would be expected to hamper the processing of complex information more generally. To the extent that a psychopathy-related attention bottleneck constrains simultaneous processing of picture elements and, thus, undermines the fluent processing of novel pictures, it would inhibit emotion processing. Conversely, when the perceptual demands of processing the pictures are reduced, by presenting familiar information, limitations associated with the attentional bottleneck should abate, and psychopaths should show normal emotion processing.

Our findings for emotion-modulated startle supported these a priori hypotheses regarding the attention bottleneck model. Replicating previous research (Patrick et al., 1993; Vaidyanathan, et al., 2011), individuals high on psychopathy displayed deficient emotion-modulated startle during novel trials. However, this finding did not fully characterize the underlying deficit that is operating in psychopathy. The familiarity manipulation ameliorated the psychopathy-based emotion-modulated startle deficit. While reducing the processing requirements associated with the processing of novel pictures resulted in greater emotion-modulated startle responses across all participants, the manipulation had a differential impact on psychopathic individuals. The fact that psychopathic individuals displayed normal emotion-modulated startle with familiar pictures, but deficits with novel pictures, supports our proposal that the perceptual demands associated with processing novel pictures are more costly for psychopathic individuals (presumably owing to their attention bottleneck) and sufficient to undermine their affective response.

This conclusion regarding the crucial importance of perceptual load on emotion-modulated startle in psychopathy is further supported by a study that manipulated picture complexity to examine its effects on startle in a community sample of psychopathic individuals (Sadeh & Verona, 2012). Paralleling our findings differentiating novel versus familiar pictures, psychopathic participants displayed a deficit in startle potentiation while viewing pictures with high perceptual load (e.g., complex scenes), but showed no deficit while viewing pictures with low perceptual load (e.g., simple figure-ground images). Combined with the present study, these results strongly suggest that perceptual load differentially impacts picture processing and emotional reactivity in psychopathic individuals.

An additional goal of our study was to reconcile the discrepancy between the emotion-modulated startle findings obtained using the traditional novel picture-viewing paradigm and those obtained using instructed fear paradigms. During instructed fear conditioning, psychopathic individuals display deficient fear-potentiated startle if their attention is already engaged in processing other information (e.g., case of a letter), yet they display normal fear responses when instructed to focus on threat cues (i.e., color that connotes threat of shock; Baskin-Sommers et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2010). While the attention manipulation moderated the psychopathy-related fear deficit, the mechanism implicated in these studies is an attention bottleneck that constrains the integration of peripheral threat information when attention is otherwise engaged. Thus, regardless of whether the effects of the bottleneck are shown by manipulating overt attention through instructions or perceptual demands via the familiarity or complexity of pictures, it is clear that psychopathic individuals have difficulty attending to and processing multiple channels of information simultaneously. Together, these studies indicate that an attention bottleneck may account for the psychopathy-based emotion reactivity deficits across a variety of experimental contexts (i.e., including those that involve a direct focus on emotion stimuli; cf. Sylvers et al, 2011).

Beyond evidence for an attention bottleneck in affective contexts, psychopathic individuals display related abnormalities in studies using affectively neutral stimuli. In these studies, psychopathic individuals compared to controls display less distraction when their attention is occupied elsewhere or perceptual demands are high, but display comparable distractibility (i.e., interference) when task conditions prevent participants from using early selective attention or are less perceptually demanding (Hiatt, Schmitt & Newman, 2004; Sadeh & Verona, 2008; Zeier, Maxwell & Newman, 2009). Overall, the attention bottleneck model provides a parsimonious perspective on their emotion deficit that also appears to extend to other psychopathy-related deficits (e.g., language/semantic processing, attention, conflict monitoring).

The present results are very much in line with the a priori hypotheses generated by the attention bottleneck model. However, alternative interpretations are possible. Of particular relevance for emotion-modulated startle, Levenston et al. (2000) proposed that psychopathic individuals have a higher threshold for generating an affective-defensive response. Thus, in the present study, their relatively weak emotion-modulated startle in the novel condition may indicate a specific deficit in defensive system reactivity. Proponents of this view might then speculate that this threshold is overcome in the familiar condition owing to the greater strength of the emotion stimuli in this condition. The link between a weak defensive system that increases the threshold for observing emotion-modulated startle is eminently reasonable, particularly for unpleasant or fear-related stimuli. However, there is a lack of direct evidence to substantiate this association in psychopathy. To provide a direct test of this hypothesis, it would be crucial to manipulate the bottom-up emotional intensity of the picture stimuli and demonstrate that the psychopathic deficit appears and disappears as a function of emotion intensity. In contrast to the evidence highlighting the importance of attention, to our knowledge, there are no existing studies that use a manipulation to address the threshold for emotion-modulated startle in psychopathy.

Though some may wish to interpret our familiarity manipulation as affecting emotion intensity, it is important to note that pictures were randomly assigned as novel/familiar across participants and thus were not inherently different with regard to bottom-up emotional salience. Rather, the perceptual demands associated with processing the pictures assigned to novel versus familiar trials were different (Ferrari et al., 2010). Furthermore, the fact that psychopathic individuals displayed deficient startle modulation to emotionally pleasant as well as emotionally unpleasant stimuli provides further evidence that attention limitations rather than the nature of the bottom-up elicitor underlies their insensitivity to affective information. Thus, while the elevated threshold model merits further attention, the present results are more consistent with the attention bottleneck model.

Late Positive Potential

To the extent that an attention bottleneck limits multi-channel processing, it follows that this abnormality would not only interfere with emotion-modulated startle, but also with the affective elaboration of perceptually demanding (i.e., novel) pictures. To evaluate this prediction, we measured the LPP response, which is thought to reflect the recognition and elaborative processing of salient stimuli (Hajcak et al, 2010). Contrary to predictions, psychopathy was unrelated to LPP responses during novel trials. Furthermore, although participants displayed greater overall LPP responses in the familiar versus novel condition, the LPP differentiation between affective and neutral pictures was inversely related to psychopathy scores (i.e., weaker for psychopathic individuals). Thus, despite the familiarity of the pictures, psychopathy was associated with significantly less elaborative processing. Although unexpected, the LPP results provide new insight into the psychopathy-related processing deficit and its impact on complex affective processes.

Recent studies demonstrate that the LPP is not only sensitive to the emotional content of pictures but also the way in which that content is processed and appraised. For instance, Keil and colleagues (2005) found that directed attention operates in conjunction with emotion to evoke the LPP (Foti & Hajcak, 2008). Thus, the LPP not only reflects an initial response to stimulus salience, but is also modulated by top-down processes like directed attention and cognitive control (Hajcak, Dunning, & Foti, 2008). Moreover, the contributions of these cognitive–affective processes may differentially impact elaborative processing throughout the time-course of the LPP (Weinberg, Hilgard, Bartholow & Hajcak, 2012).

The LPP response appears to index two stages of processing, one at an early stage of salience detection, potentially prior to the assignment of valence, and a second at a later elaborative stage after the valence assignment. Because the amount of voluntary elaboration that can be done is necessarily limited for everyone while viewing novel pictures, the LPP may primarily reflect a response to salience detection during these trials. Consistent with this view, we found a main effect of familiarity with smaller LPP responses on novel than on familiar trials. Thus, the absence of psychopathy-related differences in the novel picture condition does not necessarily indicate normal affective elaboration among psychopathic individuals. Rather, the restricted possibility for top-down processing among all participants may have limited the opportunity to observe significant psychopathy-related differences in elaborative processing.

In contrast to novel trials, individual differences in LPP responses were apparent on familiar trials. The specificity of this pattern suggests that, in line with the LPP literature, the availability and flexibility of top-down resources is essential for appraising and integrating affective information. Specifically, when attention was more readily available due to the reduced demands associated with processing familiar versus novel pictures, individuals with low psychopathy scores directed more attention to the emotion content and displayed larger affective modulation of the LPP response. This increased elaboration of affective content�may reflect a combination of habit (i.e., orienting to emotion cues owing to their potential importance) and the prior acquisition of experience-based associations, which strengthen one's inclination to direct attention accordingly (Damasio, 1994). Conversely, increased picture familiarity had relatively little effect on the elaboration of affective significance displayed by psychopathic individuals. This lack of elaboration is in need of further study, but may reflect a combination of detachment from or disinterest in affective information (Birbaumer et al., 2005; Kiehl et al., 2001; Levenston et al., 2000) and/or the effects of an attentional abnormality (e.g., attention bottleneck) on the acquisition of experience-based associations (Blair, 1995, 2008; Damasio, 1994; Motzkin, Newman, Kiehl & Koenigs, 2011).

Integration of Psychophysiological Measures

Because we did not predict the differential pattern of results for emotion-modulation startle and LPP was unexpected, our interpretation of this difference is necessarily speculative. Nevertheless, it is important to attempt to reconcile the findings with our a priori predictions. The startle response is a reflexive blink that is modulated by sensory, attentional, and affective processes (Bradley, Codisposti & Lang, 2006). This blink response measures a generally low-level process and once the emotion quality of a picture is perceived, it modulates the startle response. Conversely, the LPP response, is more closely tied to and dependent upon top-down elaborative processing. In the present study, while the familiarity manipulation normalized the emotion-modulated startle response in psychopathic individuals, it did not do so for the LPP. This difference highlights a potentially important distinction between a momentary reaction and one that is influenced by prior experience.

More specifically, we propose that the cumulative effects of limited processing, necessitated by an attention bottleneck, constrain the internalized network of associations related to various stimulus contexts (Patterson & Newman, 1993; Newman & Lorenz, 2003) and give rise to a deficit in affective elaboration. To the extent that a person’s associative network for emotion stimuli is limited, their proclivity to attract (i.e., reorient) and hold (i.e., promote a chain of elaborative processing) attention may be correspondingly limited (Blair, 1995; Damasio, 1994). Thus, the network of associations related to ongoing evaluations of one’s own and other’s behavior, thoughts, and emotions may be correspondingly impoverished.

In the present study, for psychopathic individuals, it is possible that the perceptual demands and compulsory engagement of the bottleneck during novel pictures constrained their emotion-modulated startle response, but masked their elaborative deficit. However, once the bottleneck was less crucial, psychopathic individuals displayed valence-related emotion-modulated startle; but a secondary deficit in the later stages of affective elaboration emerged. While the familiarity manipulation appears to have been successful in reducing demands on attention, the subsequent tendency to allocate spare capacity to emotion cues and elaborate on their meaning appears to be less well developed among psychopathic individuals. Though this interpretation is speculative, it serves to accommodate the current findings, provides a novel perspective on the core features of psychopathy (e.g. callousness, superficiality, antisocial behavior), and suggests an interesting direction for future research (i.e., developmental trajectory of multiple processing deficits).

Factors of Psychopathy

Factor analyses of multiple measures of psychopathy reveal a reliable two-factor structure: Factor1 (Affective/Interpersonal) and Factor2 (Impulsive/Antisocial). Purportedly, Factor1 corresponds to an amygdala-mediated deficit in defensive reactivity, as evidenced by the Factor1-related deficit in startle response to unpleasant versus neutral pictures. Alternatively, Factor2 reflects a deficit in top-down processes that interferes with a person’s capacity to process affective information, indirectly results in weak defensive system reactivity, and undermines inhibition of maladaptive approach behavior (Patrick, 2007). Thus, this dual-deficit model postulates distinct etiologies for Factor1 and Factor2. The results of the present study are largely consistent with this view regarding the unique variance associated with the psychopathy factors.

In the present study, Factor1 was not associated with a deficit in emotion-modulated startle but, as predicted by the dual-deficit model, the specific comparison involving unpleasant versus neutral pictures during novel trials revealed a significant Factor1-related deficit in startle potentiation. Importantly, early reports of the Factor1-related deficit in emotion-modulated startle evaluated Factor1 as a grouping variable based on individuals being above the midpoint of the PCL-R Factor2 and above the mean on Factor1 (e.g., Patrick et al., 1993). Thus, it is difficult to know whether the emotion-modulated startle effects would have been observed in these early studies had Factor1 been analyzed as a continuous variable. With regard to LPP, there were no significant Factor1 effects. The specificity of the Factor1 effect to the unpleasant versus neutral contrast in novel trials is highly consistent with previous studies (Sadeh & Verona, 2012; Vaidyanathan et al., 2011) and with the proposed unique association between Factor1 and defensive reactivity.

With regard to Factor2, not only did individuals high on Factor2 display the same selective deficit in emotion-modulated startle as reported with the PCL-R total score, but also Factor2 scores were uniquely associated with the LPP deficit. Consistent with the dual-deficit model, these findings suggest that Factor2 scores were associated with the inefficient use of top-down processing and that this limitation affected their emotion processing, resulting in selective reactivity (e.g., emotion-modulated startle) and elaboration (e.g., LPP) deficits. Moreover, the deficit in top-down processing was modulated by familiarity, providing further evidence that their anomalous emotion processing is related to cognitive/perceptual load.

Whereas the dual-deficit model focuses on the unique variance associated with the two major psychopathy factors, other approaches to psychopathy focus on the entire or unitary construct (e.g., PCL-R total scores; Hare & Neumann, 2009). The attention bottleneck model, for instance, was developed to address the unitary construct of psychopathy. While these different approaches to studying psychopathy focus on different constructs and corresponding mechanisms, they are not necessarily inconsistent. For instance, it is entirely possible that the unique variance associated with Factor1 and Factor2 relates to deficiencies in defensive reactivity and top-down processing respectively, whereas Psychopathy involves an attention bottleneck that, dependent upon the situational context, interacts with the unique variance of the factors to determine the callous, unemotional, and disinhibited traits associated with the psychopathy construct. Further, understanding the unique and unitary contributions that interact to influence these phenotypic expressions may be a fruitful avenue for future research.

Potential limitations and alternative interpretations

The goal of this study was to examine the impact of an information-processing deficit on affective processing in psychopathic individuals. Toward this end, the design used a controlled manipulation that matched affective content and altered the perceptual load of pictures. Given the novelty of this manipulation in psychopathy research, it is important to consider elements of the design that may confound the interpretation of our effects. Two issues warrant further consideration.

The first pertains to the sensitivity of experimental conditions to individual differences (Lissek, Pine, & Grillon, 2006). According to Lissek, et al., a strong experimental condition refers to a context where there are unambiguous stimuli that reliably elicit affective reactions, likely across all individuals. Conversely, a weak experimental condition is a less well-defined experimental context and as a result allows for the emergence of individual differences more so than the strong situation. With regard to the present results, since the familiar pictures elicited a stronger valence response (i.e., significant familiarity × valence interaction), these pictures may be so powerful that they restrict individual variability in affective reactivity and thus the likelihood of detecting individual differences during familiar trials. While it is possible that psychopathy-related differences in emotion-modulated startle are found more readily in the weak fear condition (e.g., novel pictures), Sadeh and Verona (2012) reported that the magnitude of the valence effect was matched across complex and simple pictures; yet they still found a parallel psychopathy by perceptual load interaction. Such consistency across studies diminishes concern that the psychopathy-related deficit is contingent upon sensitivity of the experimental conditions and bolsters confidence that the deficit is moderated by perceptual load as predicted by the attention bottleneck model.

The second issue relates to the impact of our experimental manipulation on attention to the noise probes and concomitant effects on the startle response. Specifically, because the magnitude of startle responses to noise probes may be influenced by manipulations that increase attention to and anticipation of noise probes (Anthony & Graham, 1985), it is important to consider the relevance of this relationship for the current findings. Within the current study, it is possible that more attention was directed to the noise probe during the familiar versus novel pictures. That is, if participants found the familiar pictures less engaging than the novel pictures, they may have allocated more attention to the probe during familiar pictures, resulting in larger startle responses.

While this methodological issue may influence the magnitude of the familiarity main effect, it is less clear how attention to the probe could account for the psychopathy-related differences in emotion-modulated startle that were moderated by affective valence. Presumably, the differences in attention to probe that might have resulted from the familiarity manipulation were constant across pleasant and unpleasant pictures. Additionally, the use of intermixed trials reduces concern that participants engaged the pictures in a modality-specific set-like manner because the unpredictability about whether a picture will be novel or familiar limits the amount of preparatory engagement that can occur.

While these methodological issues are important to consider, the present findings are rooted in a strong theoretical perspective and are consistent with a number of studies across experimental contexts. In the present study, our manipulation of familiarity demonstrated the differential importance of perceptual load for the affective processing of psychopathic individuals. Combined with the results of previous studies, these findings indicate that continuing to clarify the anomalous cognitive-emotional interactions associated with psychopathy is a promising avenue for future research.

Conclusions

Overall, the current findings highlight the importance of processing load in determining when psychopathic individuals do and do not display emotion deficits. Furthermore, the combination of emotion-modulated startle and LPP findings serve to highlight different stages at which affective processing in psychopathic individuals can be constrained by limitations in information-processing. Given the central role of attention in moderating sensitivity to important environmental cues in diverse experimental settings, including affectively neutral as well as emotion stimuli (see Newman & Baskin-Sommers, 2011), there is reason to believe that the attention bottleneck may be a crucial factor hampering affective processing in psychopathic individuals. An important direction for future research, then, is to refine the assessment of the attentional and emotional deficits in psychopathy, and specify their impact on diverse components of psychopathic behavior. For example, the use of additional measures of attention (e.g., different tasks, psychophysiological measures of attention) and/or bottom-up reactivity (i.e., fear reactivity) and possibly other conceptually related individual difference measures (i.e., fearlessness), would help to bridge the gap between the cognitive-affective deficits and their ultimate expression in psychopathic symptoms.

Footnotes

Slides were selected from the International Affective Picture System (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008). The slide numbers were: Pleasant: 4607, 4609, 4641, 4650, 4680, 4690, 5621, 8030, 8034, 8180, 8420, 8190; Neutral: 2440, 2480, 5510, 2570, 2870, 7010, 7060, 7100, 7130, 7175, 7491, 9360; Unpleasant: 3060, 3071, 3110, 3530, 3500, 6244, 6250, 6260, 6370, 6510, 6560, 6570.

The original studies on emotion-modulated startle deficits in psychopathy examined psychopathy using groups that identified individuals who were psychopathic or non-psychopathic (e.g., Patrick et al., 1993). As recommended by the PCL-R manual, participants scoring 30 or more on the PCL-R are classified as psychopathic and those scoring 20 or less as nonpsychopathic. Consistent with the continuous analyses, the valence contrast was moderated by psychopathy and familiarity (i.e., Psychopathy X Familiarly X valence contrast), F(1,63)=8.27, p=.01, ηp2=.12. Compared to non-psychopathic individuals, psychopathic individuals displayed a deficit in emotion-modulated startle during the novel trials (F(1,63)=6.85, p=.01, ηp2=.10), but there was no difference in emotion-modulated startle between psychopathic and non-psychopathic individuals during the familiar trails (F(1,63)=.-67, p = .80). More specifically, nonpsychopathic individuals displayed greater emotion-modulated startle (ηp2=.28) than psychopathic (ηp2=.07) individuals during novel trials. In contrast, during familiar trials, nonpsychopathic (ηp2=.43) and psychopathic individuals (ηp2=.45) displayed comparable emotion-modulated startle. Of note, psychopathic individuals also displayed significantly greater emotion-modulated startle during familiar trials than novel trials.

To supplement the primary analyses, we also tested follow-up simple interactions using unpleasant vs. neutral comparisons. For novel trials, the Psychopathy X unpleasant vs. neutral interaction was marginal, F(1,134)=3.05, p=.08, ηp2=.02, with the magnitude of the unpleasant vs. neutral contrast decreasing as psychopathy scores increased. However, there was no significant Psychopathy X unpleasant vs. neutral interaction for familiar trials, F(1,134)=1.96, p=.16.

Of the 136 participants, 25 participants were rejected due to the criteria set for blink correction (i.e., identification of a maximum blink and a minimum of 20 blinks) and 5 were rejected for too many too many artifactual trials (more than 20% of trials with artifact). In addition, 4 outliers (Studentized residuals with Bonferroni-corrected p-values < .05) were excluded from analyses. Thus, the final sample size for LPP analyses was reduced to 102 inmates.

References

- Anthony BJ, Graham FK. Blink reflex modification by selective attention: Evidence for the modulation of “automatic” processing. Biological Psychology. 1985;21:43–59. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(85)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers AR, Newman JP. Differentiating the Cognition-Emotion Interactions that Characterize Psychopathy versus Externalizing Disorders. In: Robinson M, Harmon-Jones E, Watkins E, editors. Cognition and Emotion. New York: Guilford Press; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers AR, Curtin JJ, Newman JP. Specifying the attentional selection that moderates the fearlessness of psychopathic offenders. Psychological Science. 2011;22(2):226–234. doi: 10.1177/0956797610396227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbaumer N, Veit R, Lotze M, Erb M, Christiane H, Grodd W, Flor H. Fear conditioning in psychopathy: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:799–805. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. A cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopath. Cognition. 1995;57:1–29. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00676-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Newman CC, Mitchell DGV, Richell RA, Leonard A, Morton J, Blair RJR. Differentiating among prefrontal substrates in psychopathy: Neuropsychological test findings. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:153–165. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex: functional contributions and dysfunction in psychopathy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 2008;363:2557–2565. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Hamby S, Low A, Lang PJ. Brain potentials in perception: Picture Complexity and emotional arousal. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Lang PJ. A multi-process account of startle modulation during affective perception. Psychophysiology. 2006;43:486–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ, Cuthbert BN. Emotion, Novelty, and the Startle Reflex: Habituation in Humans. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993;107:970–980. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Codispoti M, Ferrari V, Bradley MM. Repetition and Event-related Potentials: Distinguishing Early and Late Processes in Affective Picture Perception. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;19:577–586. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JJ. PhysBox: The Psychophysiology toolbox. A Matlab toolbox for reducing psychophysiological data within EEGLab. 2011 http://dionysus.psych.wisc.edu/PhysBox.htm.

- Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR. Descartes’ error: emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: G. P. Putnam; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari V, Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Lang PJ. Repetitive exposure: Brain and reflex measures of emotion and attention. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:515–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion DL, Dawson ME, Schell AM. Modification of the acoustic startle-reflex eyeblink: A tool for investigating early and late attentional processes. Biological Psychology. 1993;35:185–200. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(93)90001-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forth AE, Hare RD. The contingent negative variation in psychopaths. Psychophysiology. 1989;26:676–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb03171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Deconstructing reappraisal: Descriptions preceding arousing pictures modulate the subsequent neural response. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:977–988. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KD, Schmitt WA, Newman JP. Stroop tasks reveal abnormal selective attention among psychopathic offenders. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:50–59. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Dunning JP, Foti D. Motivated and controlled attention to emotion: Time-course of the late positive potential. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;3:505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, MacNamara A, Olvet DM. Event-Related Potentials, Emotion, and Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:129–155. doi: 10.1080/87565640903526504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Electrodermal and cardiovascular correlates of psychopathy. In: Hare RD, Schalling D, editors. Psychopathic behavior: Approaches to research. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1978. pp. 107–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Manual for the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. 2nd ed. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. Psychopathy: Assessment and forensic implications. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54:791–802. doi: 10.1177/070674370905401202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillyard SA, Vogel EK, Luck SJ. Sensory gain control (amplification) as a mechanism of selective attention: Electrophysiological and neuroimaging evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1998;393:1257–1270. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Mechanisms of visual attention in the human cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2000;23:315–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Moratti S, Sabatinelli D, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Additive effects of emotional content and spatial selective attention on electrocortical facilitation. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1187–1197. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA, Smith AM, Hare RD, Mendrek A, Forster BB, Brink J, Liddle PF. Limbic abnormalities in affective processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:677–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA. A cognitive neuroscience perspective on psychopathy: Evidence for paralimbic system dysfunction. Psychiatry Research. 2006;142:107–128. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. Technical Report A-8. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Levenston GK, Patrick CJ, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. The psychopath as observer: Emotion and attention in picture processing. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:373–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Pine DS, Grillon C. The strong situation: A potential impediment to studying the psychobiology and pharmacology of anxiety disorders. Biological Psychology. 2006;72:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT. A study of anxiety in the sociopathic personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1957;55:6–10. doi: 10.1037/h0047232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT. The Antisocial Personalities. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Moratti S, Saugar C, Strange BA. Prefrontal-Occipitoparietal Coupling Underlies Late Latency Human Neuronal Responses to Emotion. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:17278–17286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2917-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzkin J, Newman JP, Kiehl K, Koenigs M. Reduced prefrontal connectivity in psychopathy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:17348–17357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4215-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Baskin-Sommers AR. Early Selective Attention Abnormalities in Psychopathy: Implications for Self-Regulation. In: Poser M, editor. Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 421–440. [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Curtin JJ, Bertsch JD, Baskin-Sommers AR. Attention moderates the fearlessness of psychopathic offenders. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.035. PMCID: PMC2795048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Lorenz AR. Response modulation and emotion processing: Implications for psychopathy and other dysregulatory psychopathology. In: Davidson RJ, Scherer K, Goldsmith HH, editors. Handbook of Affective Sciences. Oxford: University Press; 2003. pp. 904–929. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson JK, Polich J. Affective visual event-related potentials: Arousal, repetition, and time-on-task. Biological Psychology. 2007;75:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ. Emotion and psychopathy: Startling new insights. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ. Getting to the heart of psychopathy. In: Herve H, Yuille JC, editors. The psychopath: Theory, research, and social implications. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 207–252. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Emotion in the criminal psychopath: Startle reflex modulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:82–92. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CM, Newman JP. Reflectivity and learning from aversive events: toward a psychological mechanism for the syndromes of disinhibition. Psychological Review. 1993;100(4):716–736. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:437–442. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, Verona E. Visual complexity attenuates emotional processing in psychopathy: Implications for fear-potentiated startle deficits. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;12:346–360. doi: 10.3758/s13415-011-0079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, Verona E. Psychopathic traits associated with abnormal selective attention and impaired cognitive control. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:669–680. doi: 10.1037/a0012692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Vitale JE, Newman JP. Emotion among females with psychopathy during picture perception. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:610–619. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvers PD, Brennan PA, Lilienfeld SO. Psychopathic Traits and Preattentive Threat Processing in Children: A Novel Test of the Fearlessness Hypothesis. Psychological Science. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0956797611420730. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan U, Hall JR, Patrick CJ, Bernat EM. Clarifying the Role of Defensive Reactivity Deficits in Psychopathy and Antisocial Personality Using Startle Reflex Methodology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:253–258. doi: 10.1037/a0021224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Hilgard J, Bartholow BD, Hajcak G. Emotional targets: Evaluative categorization as a function of context and content. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2012;84:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachary RA. Shipley institute of living scale: Revised manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Service; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zeier JD, Maxwell JS, Newman JP. Attention moderates the processing of inhibitory information in primary psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:554–563. doi: 10.1037/a0016480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]