Abstract

Current therapies for transplant rejection are sub-optimally effective. In an effort to discover novel immunosuppressants we used cytokine ELISPOT and ELISAs to screen extracts from 53 traditional Chinese herbs for their ability to suppress human alloreactive T cells. We identified a dichloromethane-soluble fraction (QMAD) of Qu Mai (Dianthus superbus) as a candidate. HPLC analysis of QMAD revealed 3 dominant peaks, each with a MW ~600 Daltons and distinct from cyclosporine and rapamycin. When we added QMAD to human mixed lymphocyte cultures, we observed dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation and IFNγ production, by naïve and memory alloreactive T cells, and observed an increased frequency of Foxp3+CD4+ T cells. To address whether QMAD induces regulatory T cells we added QMAD to anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated naïve CD4 T cells and observed a dose-dependent upregulation of Foxp3 associated with new suppressive capacity. Mechanistically, QMAD did not induce T cell IL-10 or TGFβ but blocked T cell AKT phosphorylation, a key signaling nexus required for T cell proliferation and expansion, that simultaneously prevents Foxp3 transcription. Our findings provide novel insight into the anti-inflammatory effects of one traditional Chinese herb, and support the need for continued isolation, characterization and testing of QMAD-derived components as immune suppressants for transplant rejection.

Keywords: Immunosuppression, T cell, human, Treg

INTRODUCTION

Transplantation is a life-saving treatment for end stage heart, liver and lung failure, and provides a survival advantage over dialysis for patients with end stage kidney disease (1, 2). Over the past 2 decades, improvements in clinical care and the addition of multiple immunosuppressant strategies have reduced short term morbidity following organ transplantation and lowered rates of acute rejection episodes for all types of transplants (3, 4). Nonetheless, acute rejection continues to cause morbidity (3, 4). Commonly used immunosuppressants have multiple toxic, off target effects (3, 4), can inhibit protective regulatory T cell (Treg) formation and function (5) and their use has not significantly improved the incidence or kinetics of late graft failure (6, 7). Memory T cells reactive to donor antigens represent one important barrier to improved transplant outcomes as memory T cells are resistant to most currently used immunosuppressants (8) and the presence of anti-donor memory confers an increased risk for poor outcome following transplantation (9–11). Taken together, these observations support the need to identify additional immunosuppressants for use in transplantation, specifically compounds that are simultaneously Treg-protective and capable of blocking memory T cells.

Traditional Chinese herbal medicine (TCM), used for centuries to treat a wide array of illnesses, has received attention in recent years as potential therapy for a variety of immune mediated disorders. Studies by our group and others indicate that standardized extracts of TCM, and isolated compounds derived from these extracts, have efficacy in preventing and/or treating food allergy, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis in humans (12–15). While several TCM-derived compounds have been shown to limit alloreactive T cell responses in animal models (16–18), whether and how TCM impacts human alloimmunity has not been carefully explored. To this end, we screened 53 Chinese herbal extracts for their potential ability to suppress human alloimmune responses and identified Qu Mai (QM, Dianthus superbus) as a candidate immunosuppressant. We report here that a non-polar fraction of Qu Mai extracted with dichloromethane suppresses naïve and memory alloreactive T cells while simultaneously and directly generating Treg. Our findings support the need for continued isolation and testing of the active components of Qu Mai as potential immune suppressants to improve transplant outcomes.

METHODS

Human Subjects

Blood samples were obtained from normal volunteers following approval by the Institutional Review Board at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. In some experiments PBMC were obtained from commercially purchased buffy coats from de-identified donors.

Cell isolation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll separation using standard methods (19). Primary expanded B cell lines used as stimulator cells were produced from CD19-enriched PBMC by in vitro culture with CD40L-transfected fibroblasts and IL-4 as previously described (19, 20). Aliquots were frozen and stored at −80°C and thawed as needed for use in various assays. CD3+ and memory CD45RO+CD8+ T cells and CD14+ cells were isolated to >90% purity using kits purchased from STEMCELL Technologies (Vancouver, B.C); naïve CD45RA+CD4+T cells were isolated using MACS® cell separation (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Dendritic cells (DC) were induced from CD14+ monocytes by incubation with GMCSF and IL-4 as described (21). Cell viability was assessed by acridine orange, ethidium bromide staining.

Preparation of herbal extracts

All medicinal herbs used in this study were from the TCM anti-inflammatory herbal inventory of the Botanical Chemistry Laboratory at Mount Sinai School of Medicine (New York). The inventory was established based on substantial literature search of the TCM herbs that have been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects and by preliminary screening of the herbs that inhibit TNF-α (unpublished data). All herb extracts were made in a good manufacturing practice facility (Gangdong Yifang Pharmaceutical CO. LTD. China), or from Xiyuan Chinese Medicine Research and Pharmaceutical Manufacturer, Chinese Academy of Chinese Medicine Sciences, Beijing China. All were water extracts prepared according to the standard procedure, and then concentrated and dried. Each powdered extract was packaged and stored at room temperature under dark and dry conditions. We screened 53 distinct herbal extracts (see supplemental Table 1). All extracts were dissolved in 25 mg/ml of CTL-T serum free media (CTL, Shaker Heights, OH) and diluted in CTL-T for use in assays.

Chemical Isolation of Qu Mai fractions and generation of HLPC fingerprints

To prepare subfractions of the QM extract we dissolved 100 g of QM in 4 L distilled water, adjusted the pH to 2.0 with HCl, and extracted the solution with HPLC grade dichloromethane (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 24hr in a liquid-liquid extractor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 100°C using a 2000mL heating mantle (Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA), yielding fraction QMAD. The aqueous phase was further extracted with 4 L ethyl acetate (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) for 30 h at 120°C (yielding QMAE), concentrated to 1L and further extracted with 1L of butanol (Fisher Scientific) using separation funnel to yield QMAB fraction. The butanol extraction (QMAB) was collected in a new container. All three extracts were dried with a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor R-210, BÜCHI, Switzerland) under vacuum.

Each of the 3 fractions, QMAD, QMAE, and QMAB, were analyzed by HPLC using Alliance 2695 HPLC system coupled with photodiode array detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). 10 µL of each QM fraction solution (5mg/mL) was separated with Zorbax SB-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm; 5µm particle size) from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA). The mobile phase A was 0.10% phosphoric acid (H3PO4) and the mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The separation gradient started at 2% of B to 25% in 45 min, increasing to 35% B in 25 min, increasing to 55% B in 15 min, increasing to 75% B in 10 min, and maintained at 75% for 5 min. The flow rate was set to 1.0 mL/min and the chromatograms were acquired at 254nm.

Cell Culture

PBMCs or enriched T cell subsets were stimulated with either soluble anti-CD3/CD28 (BD Biosciences, 1 µg/ml each), beads coated with anti-CD3/CD28 (Dynabeads, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, 25 µl/1E6 cells), HLA-disparate dendritic cells, HLA-disparate B cells ± phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) as indicated, in CTL or RPMI (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) plus 6–10% human AB serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA) for 1–5 d at 37°C 5% CO2. QM and QMAD, QMAE, QMAB fractions, or equivalent amounts of diluent (DMSO, Fisher Scientific, final concentration 0.02–0.2%) were added to the cultures where indicated. Proliferation was assessed by pre-staining the responder cells with CFSE (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and determining CFSE dilution by flow cytometry 3–5 days later. Mixed lymphocyte cultures were performed in the absence (control) or presence (experiment) of Qu Mai and QM fractions and were incubated for 24–48 hours. Cells enriched for CD3 or CD4CD45RA were cultured with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads ± QMAD ± IL-2 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, 100 U/ml) ± TGFβ (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, 5 ng/ml) in RPMI plus 10% human AB serum and assessed for Treg induction 5 days later by flow cytometry. Cells were harvested, washed and resuspended in RPMI plus 10% human AB serum with CFSE-labeled PBMCs. These cultures were then stimulated with soluble anti-CD3/CD28 and CD8 cell proliferation was measured by CFSE dilution (flow cytometry) 4 days later.

ELISPOT and ELISA

ELISPOT assays for IFNγ and IL-10 were performed as described (22). Briefly, ELISPOT plates (Millipore) were coated with primary antibodies overnight, blocked and washed. Assays were done with 300K responder PBMC mixed with medium alone, 100K stimulator B cells or phytohemagglutinin (PHA) as a positive control in CTL medium for 48 h at 37° 5% CO2. After washing, secondary antibodies and tertiary reagents were added and the plates were developed (22). The resulting spots were quantified using the ImmunospotS4 Core Analyzer (CTL, Shaker Heights, OH). ELISAs for IL-10, IFNγ, and TGFβ (BD OptEIA) were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow Cytometry

FITC-anti-CD3, PE-Cy5-anti-CD4, APC-H7-anti-CD8, PE-anti-CD45RO, FITC-anti-CD4 APC-anti-CD25, PE-Cy7-anti-IFNγ, PE-Cy7-anti IL-2 and Alexa-Fluor-647-anti-pAKT (monoclonal antibody) were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). PE and PE-Cy7-anti-Foxp3 was obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Dead cells were excluded with crystal violet staining kit (Invitrogen). For intracellular cytokine detection, Brefeldin A (eBioscience, 1:1000, for all cultures) ±16 ng/ml PMA/0.8 µM Ionomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich, for detection of IFNγ in 24-48h cultures only) was added 4 hours prior to harvest. Data was acquired on a 3 laser Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and analyzed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Group comparisons of paired data were analyzed by paired t-tests, and by Wilcoxon’s signed rank test where applicable. One-way RM ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons among treatment groups, with pairwise multiple comparison procedures performed using Holm-Sidak method or Tukey Test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Screening assays identify Qu Mai as a candidate herbal immunosuppressant

Multiple lines of evidence from our group and others suggest that a number of herbs used as traditional Chinese therapeutics could have immunomodulatory properties (23, 24) but whether any of these herbal compounds favorably inhibit human alloreactive T cell function has not been carefully evaluated. We therefore designed a screening assay in which we tested the effects of 53 herbal preparations (Supplemental Table 1) on alloreactive T cell cytokine production. We reasoned that the herbs which most robustly inhibit allo-induced production of the proinflammatory cytokine IFNγ and simultaneously augment production of the immunoregulatory cytokine IL-10 would be the strongest candidates to have clinically favorable immunomodulatory properties. We thus initiated mixed lymphocyte cultures using responder PBMCs obtained from normal volunteers mixed with allogeneic, in vitro expanded, primary (not EBV transformed) B cells as stimulators, in the presence or absence of each herb, tested at 2 concentrations. We quantified the frequency of IFNγ producing cells by ELISPOT and the concentration of IL-10 in culture supernatants of the same assay wells by ELISA.

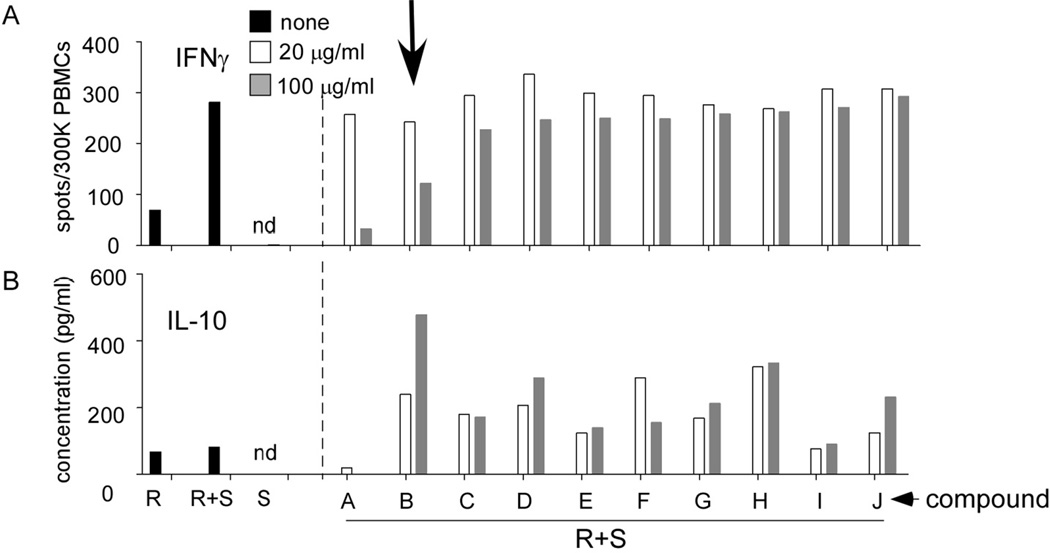

As depicted in one representative assay shown in Fig 1A allo-stimulation resulted in a significant increase in the detectable frequency of IFNγ-producing PBMC compared with unstimulated PBMC or B cell stimulators alone. Culture supernatants of PBMC with or without allo-stimulators contained low and not significantly different levels of IL-10 (Fig 1B). B cell stimulators produced no detectable IL-10 in the absence of responder PBMC. When we tested the herbal preparations (Fig 1 and supplemental Fig S1) we observed that 4 of them inhibited IFNγ production by >50% and enhanced IL-10 production by >100%. We chose to further study the immune suppressive effects of one of these herbs, Qu Mai (QM), which has been traditionally used as an anti-inflammatory agent for “urinary tract disorders” (25).

Fig. 1. TCM screening assay to identify candidate immunosuppressants.

Representative screening IFNγ ELISPOT (A) and IL-10 ELISA (B) from MLRs (single wells) ± 10 of 53 TCM herbal extracts preparations, each tested at 20 or 100 µg/ml. Results of the other 43 extracts are included in Supplemental Fig S1.

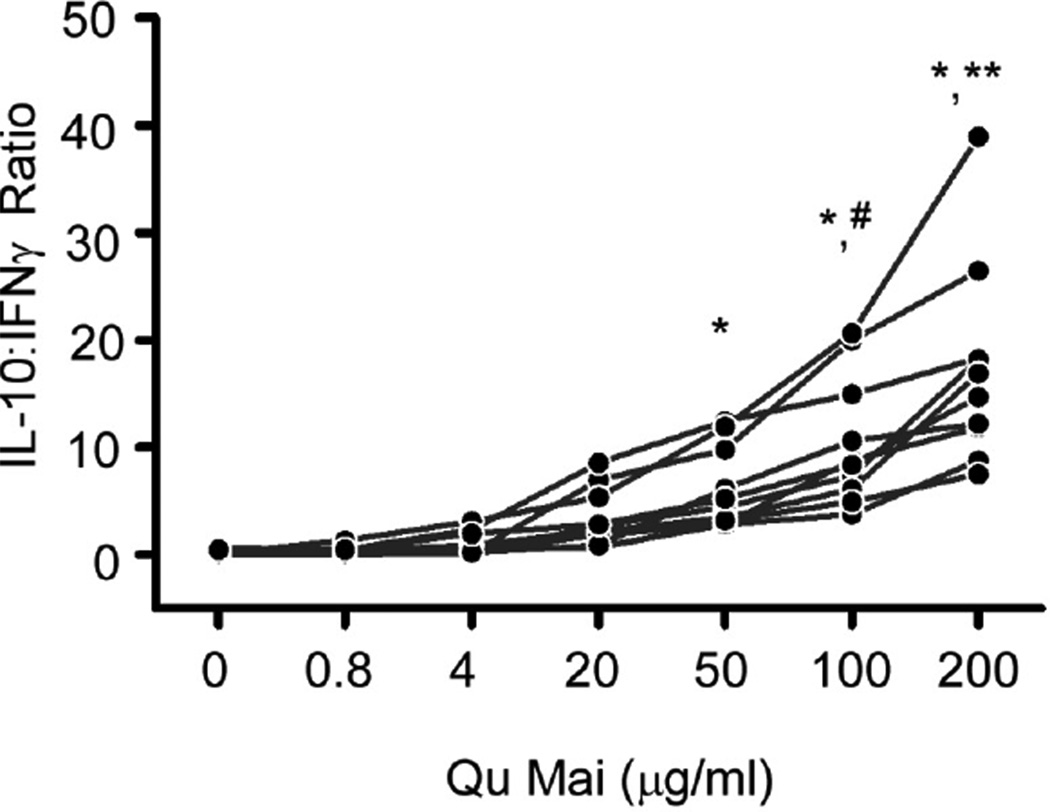

We examined concentration-dependent effects of QM on allo-stimulated production of IFNγ and IL-10 by ELISPOT using 10 distinct responder/stimulator pairs. The results revealed that QM induced a dose dependent increase in the IL-10:IFNγ ratio (Fig 2), inhibited IFNγ, and increased IL-10 production by PBMC (supplemental Fig S2) by each of the responder/stimulator pairs tested (p<0.05 at doses >20 µg/ml vs. control).

Fig. 2. Qu Mai enhances IL-10:IFNγ ratio by allogeneic PBMC.

IFNγ and IL-10 ELISPOT assays of PBMC cultured with allogeneic B cells for 48 hours ± Qu Mai (Dianthus superbus) at the concentrations depicted (10 individual responder stimulator pairs tested). Results are depicted as IL-10:IFNγ ratio. Frequencies of IFNγ-producing and IL-10-producing PBMC are shown in Supplemental Fig S2. *p<0.05 compared to 0, 0.8, and 4 µg/ml. **p<0.05 compared to 20, 50, 100 µg/ml. #p<0.05 compared with 20 µg/ml. n=10.

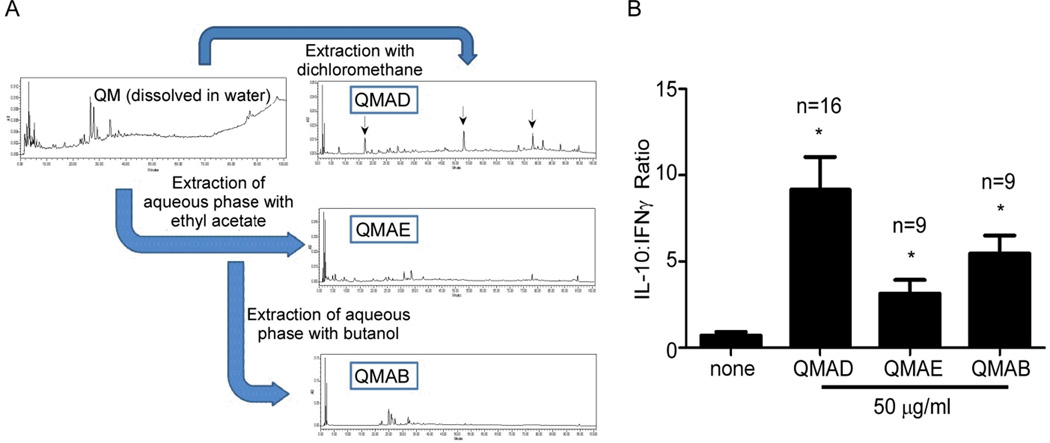

Immune effects of QM are enriched by extraction with dichloromethane

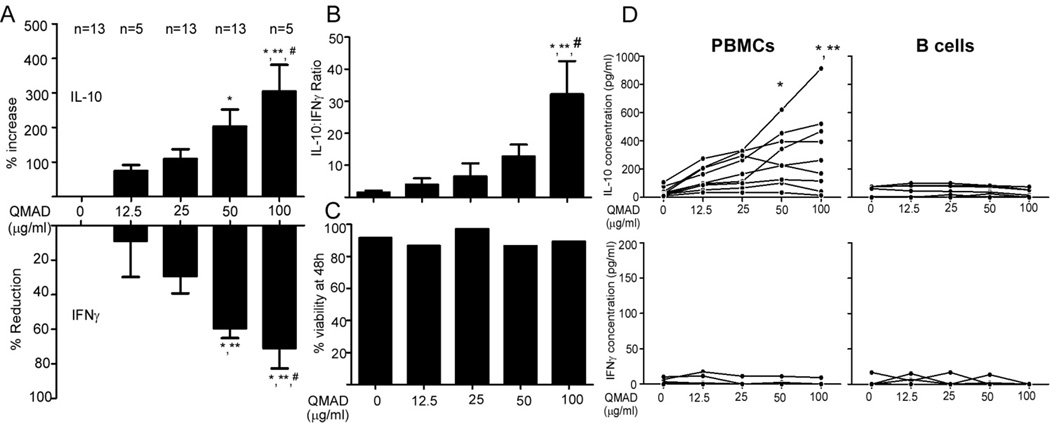

To begin to isolate active compounds from the QM herbal preparation we performed liquid-liquid extraction based on polarity, which yielded 3 fractions: dichloromethane soluble QMAD (mainly contains non-polar compounds), ethyl acetate soluble QMAE (mainly contains less polar compounds), and butanol soluble QMAB (mainly contains moderate polar compounds). HPLC analysis showed that each fraction contained multiple peaks (Fig 3A). When we tested each fraction for their effects on cytokine production using our screening MLR assay (Fig 3B) we observed that the QMAD fraction induced the most favorable effects on MLR-induced cytokines, yielding >9-fold increase in IL-10:IFNγ ratios (p<0.05 at 50 µg/ml QMAD vs. control). We assessed dose-dependence of the QMAD effects by IFNγ and IL-10 ELISA on 48h MLR supernatants (Fig 4 and Supplemental Fig S3). QMAD significantly upregulated IL-10 (mean increase of 203% at 50 µg/ml, n=13 and 305% at 100 µg/ml, n=5, Fig 4A) and inhibited IFNγ (mean decrease 61% at 50 µg/ml, n=13 and by 66% at 100 µg/ml, n=5, Fig 4A), resulting in significant increases in IL-10:IFNγ ratios (Fig 4B), in all responder/stimulator pairs tested (13-fold and 32-fold increases at 50 µg/ml and 100 µg/ml, respectively, p<0.05 for each vs. control). The number of live cells present at the end of each culture was similar regardless of QMAD concentration (Fig 4C), demonstrating that QMAD alters cytokine production without inducing cell death. In control experiments we observed that QMAD increased IL-10 production (without detectable IFNγ) when cultured with PBMC alone (in the absence of B cell stimulators, Fig 4D). QMAD had no effect on the low levels of IL-10 (and absent IFNγ) produced by B cells cultured in the absence of PBMC (Fig 4D).

Fig. 3. Fraction QMAD enhances IL-10:IFNγ ratio in MLR.

(A) Summarized methods of chemical isolation of Qu Mai fractions with corresponding HPLC chromatograms of Qu Mai and QM fractions AD, AE and AB. (B) IFNγ and IL-10 ELISPOT assays of PBMC cultured with allogeneic B cells for 48 hours ± QM fractions at the concentrations depicted. Results are depicted as IL-10:IFNγ ratios. * p<0.05 vs. control (0 µg/ml).

Fig. 4. Dose-dependent effects of QMAD on cytokine production by allostimulated PBMCs.

IL-10 (A, top) and IFNγ (A, bottom) ELISAs and calculated IL-10:IFNγ ratios (B) of PBMC cultured with allogeneic B cells for 48 hours ± QMAD at the concentrations depicted. (C) Cell viability at 48 hours as assessed by acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining. (D) Cytokine release by PBMCs or B cell stimulators cultured alone with QMAD. IFNγ and IL-10 concentrations in PBMC with and without QMAD are shown in Supplemental Fig S3. *p<0.05 vs. 0 µg/ml. **p<0.05 vs. 12.5 µg/ml. #p<0.05 vs. 25 µg/ml. No significant differences in % viability at 48h, IL-10 production by B cells, or IFNγ production by PBMCs or B cells (p>0.05).

QMAD inhibits proliferation and IFNγ production by memory CD8 T cells

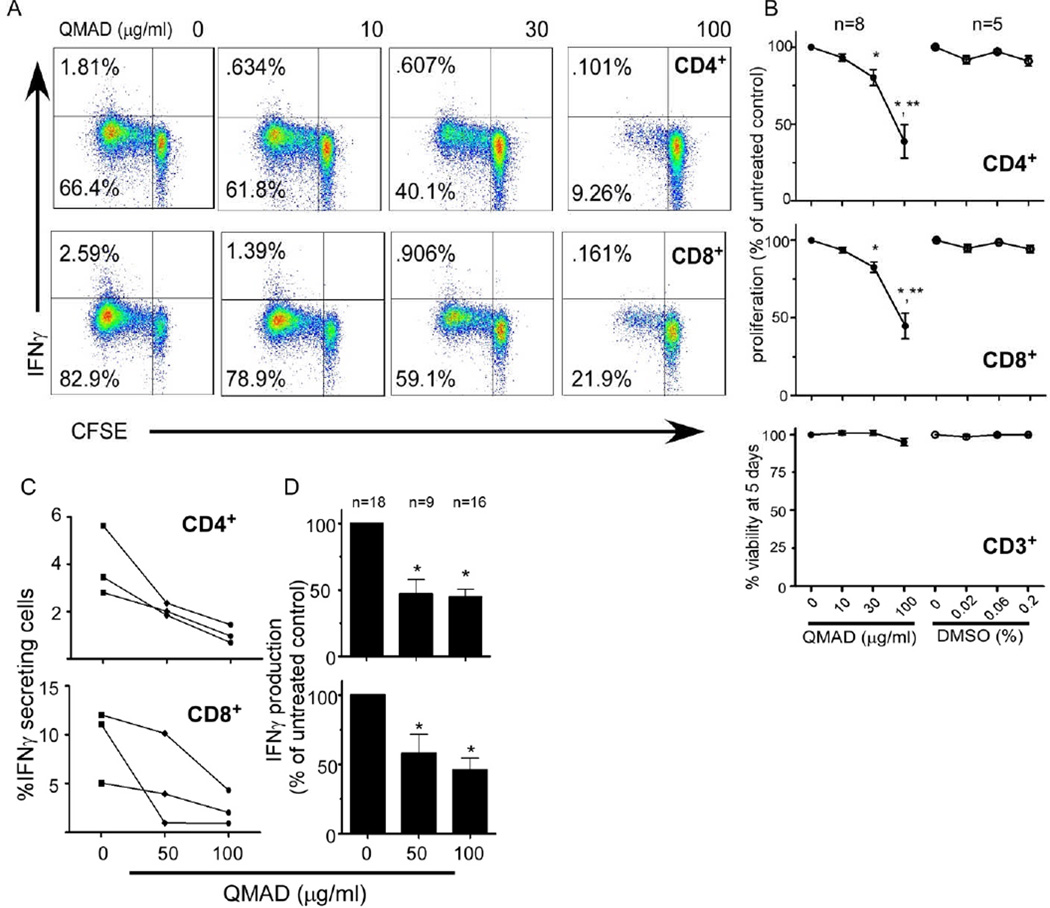

We next used flow cytometric analysis to determine effects of QMAD on CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation (CFSE dilution) and IFNγ production (intracellular staining). We observed a dose dependent inhibition of CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation in response to allogeneic DC or anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation (Fig 5A). Addition of vehicle control DMSO had no effect (Fig 5B). No IL-10 was detected in culture supernatants of these QMAD-stimulated, purified T cells (data not shown). QMAD did not alter T cell viability (Fig 5B) ruling out direct cellular toxicity. QMAD also significantly decreased IFNγ produced by CD4 and CD8 T cells in 5 day MLRs (Fig 5A) as well as in 48 h stimulations (Fig 5C and D).

Fig. 5. QMAD inhibits T cell proliferation and IFNγ production.

Representative CFSE dilution/IFNγ 2-color flow cytometry plots (A) of QMAD-treated CD4+ (top) and CD8+ (bottom) stimulated with anti-CD3/28 for 5 days. (B) Quantified results of proliferation, expressed as mean % of untreated control (normalized to 100%) ± SEM. Similar results were obtained following allogeneic DC stimulation, not shown. Cell viability is measured by flow cytometry, gated on all CD3 T cells. *p<0.05 compared to no treatment. **p<0.05 compared to 10 and 30 µg/ml. No significant difference in % viability at 5 days (p>0.05). (C) Quantified IFNγ production assessed by flow cytometry by 3 individual PBMC samples stimulated with B cells for 48 hours with PMA added 4 hours prior to cell harvest with mean % of untreated control ± SEM (D). *p<0.05 compared to no treatment.

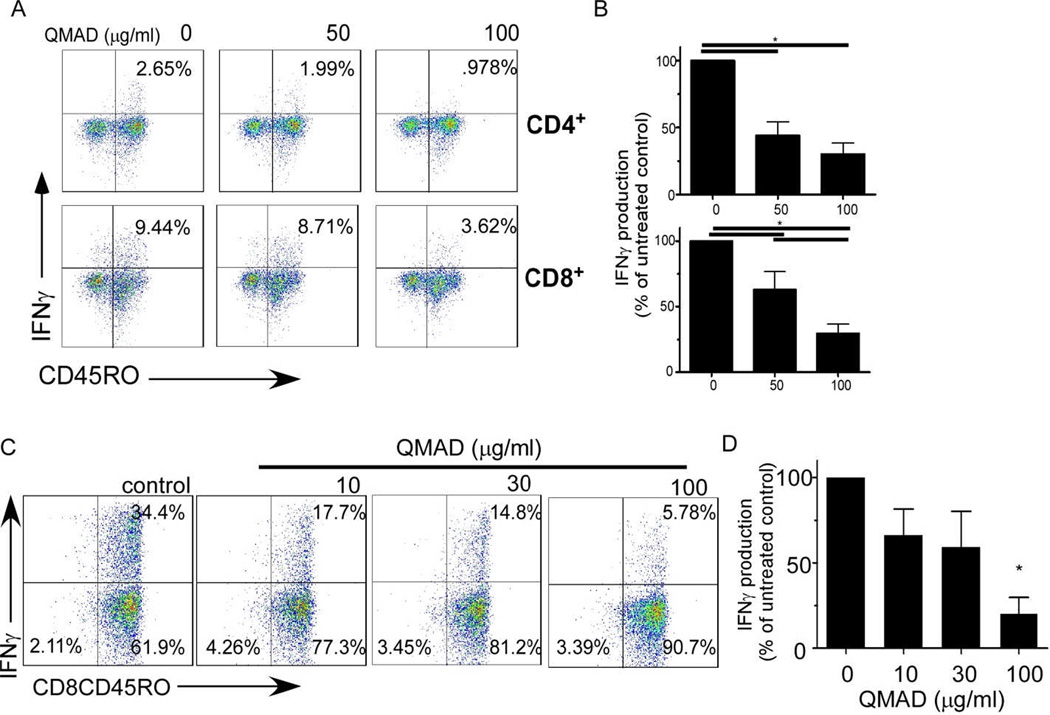

Remarkably, QMAD inhibited IFNγ production by both CD45RO+ memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within the MLRs (mean % decreases of original values to 44% and 24.5% in CD4+CD45RO+ and to 63% and 31% in CD8+CD45RO+ cells, respectively, at 50 and 100 µg/ml, Fig 6A and B). When we isolated CD8+ CD45RO+ T cells by negative selection and stimulated them with B cell stimulators for 24h ± QMAD (Fig 6C and D), we observed a dose dependent inhibitory effect even in this T cell subset known to be resistant to many forms of immune suppression (26–28).

Fig. 6. QMAD inhibits IFNγ production by memory T cells.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots of IFNγ production by CD45RO+ CD4+ (top) or CD8+ (bottom) T cells from 48-hr cultures of PBMC from a single donor stimulated with allogeneic B cells ± QMAD. PMA added 4 hours prior to cell harvest. (B) Quantification results, means ± SEM, n=11. (C) Representative flow cytometry plot of enriched CD8+CD45RO+ cells cultured ± QMAD for 48 hours with PMA added 4 hours prior to cell harvest. (D) Bars represent means (± SEM) of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. All quantified values expressed as % of untreated control, normalized to 100%. *p<0.05.

QMAD results in Foxp3+ expression by CD4+ T cells

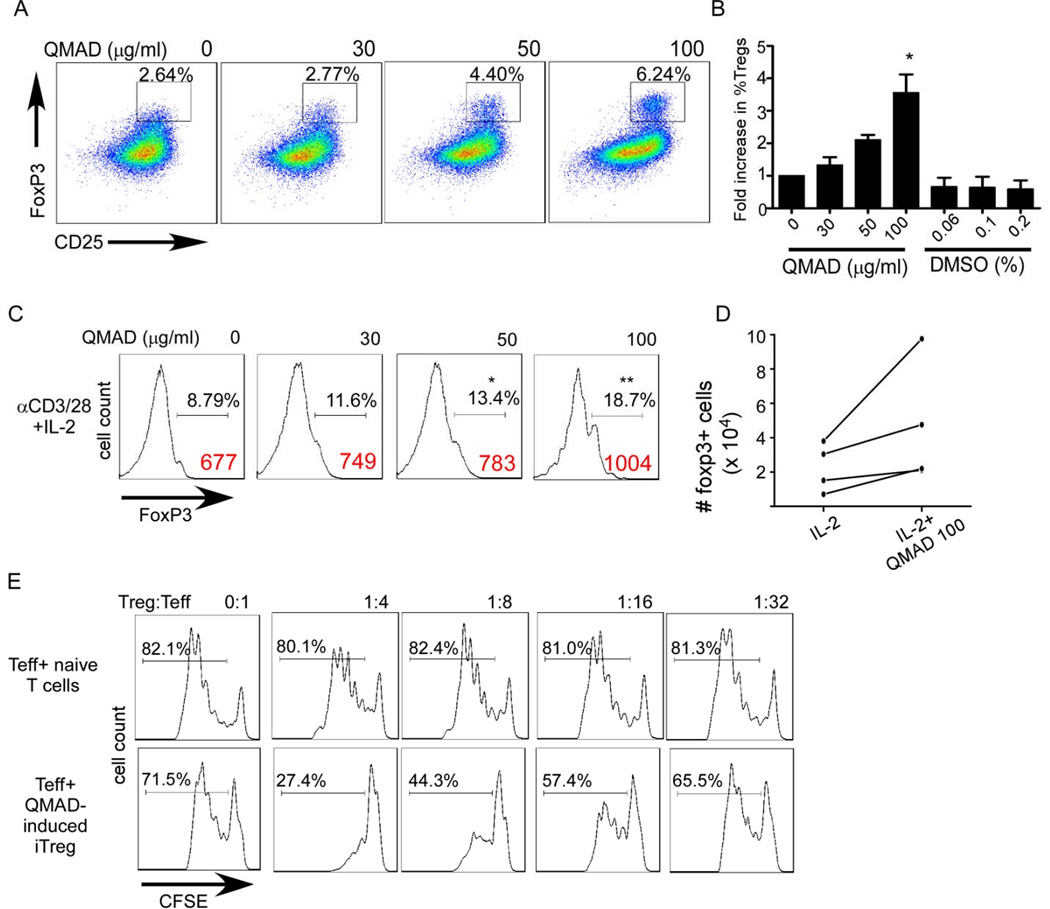

To address whether QMAD impacts Treg we quantified the frequency of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells following 5 day stimulation of unfractionated T cells enriched from PBMC with anti-CD3/CD28 (without IL-2 or TGFβ) ± varying concentrations of QMAD. We observed a dose dependent increase in the frequency of Foxp3+ CD4 T cells at the end of the culture period (Fig 7 A-B, p<0.05 at QMAD 100 µg/ml), without an effect on IL-2 production (using intracellular staining and flow cytometry, data not shown). To directly address whether QMAD induces Treg from naïve CD4 T cells, we enriched naïve CD45RA+ CD4 T cells, and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28, IL-2 ± QMAD for 5 days. QMAD induced an increase in the percentage of Foxp3+ cells (Fig 7C), increased the total number of Foxp3+ cells (Fig 7D) and showed that the induced Foxp3+ cells suppressed Teff proliferation in vitro (Fig 7E). Addition of QMAD to induction cultures that included TGFβ increased generation of Foxp3+ suppressor cells over cultures containing TGFβ alone (p<0.05, supplemental figure S4).

Fig. 7. QMAD induces Treg.

(A) Representative CD25/Foxp3 2 color flow cytometry plots of anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated CD3+ T cells ± QMAD (5 d cultures) gated on CD4 cells. (B) Quantified results of Foxp3+ cells within the CD4 gate, means + SEM of 4 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. QMAD 0–30 µg/ml. (C) Representative Foxp3 histograms of enriched CD4+CD45RA+ cells stimulated with anti-CD3/28 + IL-2 for 5 days ± QMAD and gated on CD4+CD25+ cells. % Foxp3 are mean values of 6 individual experiments. Foxp3 MFI values are shown in red. *p<0.05 vs 0, **p<0.05 vs 0, 30 and 50 µg/ml, n=6. (D) Absolute CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells in 5 day naïve CD4 T cell cultures treated with IL-2 ± QMAD. P<0.05 IL-2+QMAD, calculated using fold increase over IL-2 controls, n= 4. (E) Histograms of Teff (CFSE-labeled PBMCs, gated on CD8) cultured with QMAD-treated CD4 cells or control CD4 cells, representative of 2 individual experiments. The same PBMC were used for both assays.

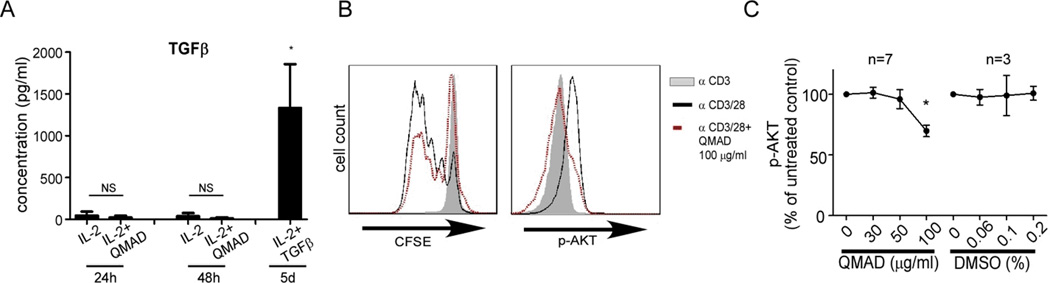

QMAD does not directly induce T cell TGFβ or IL-10 but inhibits T cell AKT phosphorylation

ELISAs performed on culture supernatants from anti-CD3/28 stimulated, naïve CD4 cells showed that QMAD (+IL-2) did not induce T cell production of detectable TGFβ (Fig 8A) or IL-10 (4 individual experiments, data not shown), negating the possibility that QMAD induced Treg via amplification of an autocrine TGFβ/IL-10 loop. In contrast, when we measured phosphorylation of intracellular AKT (protein kinase B, PKB) by flow cytometry we consistently observed that QMAD lowered expression of pAKT in CD3 T cells compared to vehicle control (Fig 8 B-C).

Fig. 8. QMAD does not increase TGFβ production by naïve CD4 cells but decreases T cell AKT phosphorylation.

(A) TGFβ measured by ELISA in Treg induction culture supernatants (with IL-2 ± QMAD) at 24 hours and 48 hours, compared to 5 day culture supernatants with TGFβ, performed in duplicate or triplicate. *p<0.05 IL-2 + TGFβ compared to all groups, n=4. (B) Representative histograms of CFSE dilution and intracellular p-AKT (assessed using monoclonal antibody) of enriched CD3+ T cells stimulated for 3 days with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3/CD28 ± QMAD. (C) Quantified results of multiple experiments performed in duplicate or triplicate (expressed as means of % of untreated control, normalized to 100%, ± SEM). *p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

Identification of immunosuppressants from natural sources has a proven track record in transplantation. Cyclosporine A was originally discovered in the fungus Tolypodadium inflatum, and sirolimus/rapamycin was first found in the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus on Easter Island. Chinese herbs, which have been used for centuries to treat a wide array of ailments, represent an untapped source of potentially useful medications for use in humans. While previously published work by our lab and others showed that various extracts of Chinese herbs have favorable immunomodulatory effects on asthma and food allergy (14, 15, 23, 29–31), our current studies newly identify that a fraction of Qu Mai (Dianthus superbus has properties likely to favorably impact transplantation. Qu Mai has traditionally been used to treat urinary tract disorders (32–34) and “inflammation”(25, 35), can suppress IgE production by human B cells and can prevent peanut allergy in mice (24), but its efficacy as an inhibitor of pathogenic alloimmunity has not been previously documented. Our data show unequivocal effects of QMAD on inhibiting proliferation and IFNγ production by naïve and memory alloreactive T cells (Figs 5 and 6) while simultaneously facilitating Treg induction (Fig 7 and Supplemental Fig S4). The observed ability of QMAD to block proliferation and cytokine secretion by memory T cells is of particular interest, as memory T cells are generally resistant to immunosuppression and have been implicated as key mediators of allograft injury (36–38).

QMAD’s simultaneous effect on the induction of Tregs is notable, in that many of the currently employed immune suppressants inhibit Treg (39), potentially limiting their long term effectiveness. While QMAD augmented Treg induction in the presence or absence of recombinant TGFβ (Fig 7 and Supplemental Fig S4) the effects were more robust when TGFβ was present; it is likely that low levels of TGFβ known to be present in serum (40) is required.

Our data suggest that QMAD induces Treg via altering intracellular signaling that limits AKT phosphorylation, rather than by inducing T cell IL-10 or TGFβ. AKT is a central nidus of T cell signaling, downstream of the TCR and costimulation. When activated by phosphorylation, pAKT activates numerous substrates that exert a plethora of cellular effects (41). Included among the latter are enhanced T cell proliferation and survival, mediated in part by upregulating expression of the anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl2 (42). Phospho-AKT also prevents Foxp3 transcription. Evidence indicates that prevention of AKT phosphorylation is required for induction and maintenance of the Treg phenotype (43). Thus, our observation that QMAD decreases pAKT in T cells provides a potential molecular link to account for the simultaneous inhibition of Teff while supporting Treg. Whether QMAD directly blocks phosphorylation of AKT, inhibits upstream signals that induce AKT phosphorylation (e.g. PI3K) and/or activates a phosphatase that dephosphorylates AKT [e.g. PHLPP (44)] remains to be determined.

While we have isolated the major immunosuppressive activity to the QMAD fraction, significant additional work will be required to identify the specific compound or compounds from within QMAD that mediate these effects. The HPLC analysis revealed 3 major peaks (Fig 3) with molecular weights of <600 Daltons each, as determined by mass spectrometry (data not shown). Based on the dichloromethane based fractionation and isolation strategy that preferentially yields non-polar, organic acid-rich compounds we believe the immunosuppressive molecules within QMAD are likely to be cyclopeptides, and that these differ from known immunosuppressants isolated from other “naturally occurring” sources, including cyclosporine A (MW 1203) and sirolimus (MW 912). Testing of in vivo immune suppression and potential toxicity will require compound purification.

One additional notable finding from our data is the proof of concept that ELISPOT based testing can be employed as a high throughput screening approach for immunosuppressive drug testing (Fig 1). We rapidly screened more than 50 candidate compounds in a simple and ultimately informative functional T cell assay that guided us toward identification of a novel immune suppressant. Interestingly, while QMAD induced production of IL-10 in the screening assays (Fig 1–4) we did not detect IL-10 in culture supernatants of purified anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated T cells+QMAD, indicating that the QMAD’s inhibitory effect on IFNγ production was not IL-10 dependent. The IL-10 in the screening assays likely derived from non T cells within the PBMC (potentially monocytes).

In conclusion, we demonstrate herein that one well-known Chinese herb, Qu Mai, contains components that favorably alter alloreactive T cell immunity toward an immune suppressive phenotype potentially useful for preventing transplant rejection among other indications. These unique findings support the need for continued efforts to isolate and characterize the active compounds from within QMAD, to test their efficacy and mechanisms in vitro, and to assess their function as adjuvant immune suppressants in transplant recipients and potentially in patients with T cell dependent, autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health T32AI078892 (JRA), and in part by U01AI063594 awarded to PSH, and AT002644725-01, 2 R01 AT001495-05A1 and Winston Wolkoff Children’s Holistic Medicine for Allergy and Asthma Foundation awarded to XML.

Abbreviations

- TCM

Traditional Chinese Medicine

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- pAKT

phosphorylated AKT

- PMA

phorbol myristate acetate

- PHA

phytohemagglutinin

- QM

Qu Mai

- QMAD

Qu Mai fraction AD

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schnuelle P, Lorenz D, Trede M, Van Der Woude FJ. Impact of renal cadaveric transplantation on survival in end-stage renal failure: evidence for reduced mortality risk compared with hemodialysis during long-term follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(11):2135–2141. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabbat CG, Thorpe KE, Russell JD, Churchill DN. Comparison of mortality risk for dialysis patients and cadaveric first renal transplant recipients in Ontario, Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(5):917–922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, Vítko S, Nashan B, Gürkan A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2562–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, Rostaing L, Bresnahan B, Darji P, et al. A phase III study of belatacept-based immunosuppression regimens versus cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study) Am J Transplant. 2010;10(3):535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeiser R, Nguyen VH, Beilhack A, Buess M, Schulz S, Baker J, et al. Inhibition of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell function by calcineurin-dependent interleukin-2 production. Blood. 2006;108(1):390–399. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kaplan B. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(3):378–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Kaplan B. Long-term renal allograft survival: have we made significant progress or is it time to rethink our analytic and therapeutic strategies? Am J Transplant. 2004;4(8):1289–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearl JP, Parris J, Hale DA, Hoffmann SC, Bernstein WB, McCoy KL, et al. Immunocompetent T-cells with a memory-like phenotype are the dominant cell type following antibody-mediated T-cell depletion. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(3):465–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heeger PS, Greenspan NS, Kuhlenschmidt S, Dejelo C, Hricik DE, Schulak JA, et al. Pretransplant frequency of donor-specific, IFN-gamma-producing lymphocytes is a manifestation of immunologic memory and correlates with the risk of posttransplant rejection episodes. J Immunol. 1999;163(4):2267–2275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augustine JJ, Siu DS, Clemente MJ, Schulak JA, Heeger PS, Hricik DE. Pre-transplant IFN-gamma ELISPOTs are associated with post-transplant renal function in African American renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(8):1971–1975. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page AJ, Ford ML, Kirk AD. Memory T-cell-specific therapeutics in organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(6):643–649. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328332bd4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Patil SP, Yang N, Ko J, Lee J, Noone S, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunologic effects of a food allergy herbal formula in food allergic individuals: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, dose escalation, phase 1 study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(1):75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang P, Li J, Han Y, Yu XW, Qin L. Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a general review. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(6):713–718. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan CK, Kuo ML, Shen JJ, See LC, Chang HH, Huang JL. Ding Chuan Tang, a Chinese herb decoction, could improve airway hyper-responsiveness in stabilized asthmatic children: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17(5):316–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen MC, Wei CH, Hu ZQ, Srivastava K, Ko J, Xi ST, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-asthma herbal medicine intervention in adult patients with moderate-severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(3):517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Zhang M, Jia H, Huang X, Zhang Q, Hou J, et al. Protosappanin A induces immunosuppression of rats heart transplantation targeting T cells in grafts via NF-kappaB pathway. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381(1):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Xu R, Jin R, Chen Z, Fidler JM. Immunosuppressive activity of the Chinese medicinal plant Tripterygium wilfordii. I. Prolongation of rat cardiac and renal allograft survival by the PG27 extract and immunosuppressive synergy in combination therapy with cyclosporine. Transplantation. 2000;70(3):447–455. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200008150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu W, Lin Z, Yang C, Zhang Y, Wang G, Xu X, et al. Immunosuppressive effects of demethylzeylasteral in a rat kidney transplantation model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(7-8):996–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poggio ED, Augustine JJ, Clemente M, Danzig JM, Volokh N, Zand MS, et al. Pretransplant cellular alloimmunity as assessed by a panel of reactive T cells assay correlates with acute renal graft rejection. Transplantation. 2007;83(7):847–852. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258730.75137.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zand MS, Bose A, Vo T, Coppage M, Pellegrin T, Arend L, et al. A renewable source of donor cells for repetitive monitoring of T- and B-cell alloreactivity. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(1):76–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2003.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Neill DW, Bhardwaj N. Differentiation of peripheral blood monocytes into dendritic cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im22f04s67. Chapter 22:Unit 22F.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebauer BS, Hricik DE, Atallah A, Bryan K, Riley J, Tary-Lehmann M, et al. Evolution of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay for post-transplant alloreactivity as a potentially useful immune monitoring tool. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(9):857–866. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li XM. Treatment of asthma and food allergy with herbal interventions from traditional chinese medicine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(5):697–716. doi: 10.1002/msj.20294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López-Expósito I, Castillo A, Yang N, Liang B, Li XM. Chinese herbal extracts of Rubia cordifolia and Dianthus superbus suppress IgE production and prevent peanut-induced anaphylaxis. Chin Med. 2011;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y-C, Tan N-H, Zhou J, Wu H-M. Cyclopeptides from Dianthus Superbus. Phytochemistry. 1998;49(5):1453–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones DL, Sacks SH, Wong W. Controlling the generation and function of human CD8+ memory T cells in vitro with immunosuppressants. Transplantation. 2006;82(10):1352–1361. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000241077.83511.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada Y, Boskovic S, Aoyama A, Murakami T, Putheti P, Smith RN, et al. Overcoming memory T-cell responses for induction of delayed tolerance in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):330–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo DJ, Weaver TA, Stempora L, Mehta AK, Ford ML, Larsen CP, et al. Selective targeting of human alloresponsive CD8+ effector memory T cells based on CD2 expression. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(1):22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li XM, Brown L. Efficacy and mechanisms of action of traditional Chinese medicines for treating asthma and allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(2):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.026. quiz 307-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang TT, Huang CC, Hsu CH. Clinical evaluation of the Chinese herbal medicine formula STA-1 in the treatment of allergic asthma. Phytother Res. 2006;20(5):342–347. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu CH, Lu CM, Chang TT. Efficacy and safety of modified Mai-Men-Dong-Tang for treatment of allergic asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16(1):76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bensky D, Clavey S, Stöger E. Chinese herbal medicine : materia medica. 3rd. ed. Seattle, WA: Eastland Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JK, Chen TT, Crampton L. Chinese medical herbology and pharmacology. City of Industry, Calif.: Art of Medicine Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu J-O, Liao Z-X, Jia-Chuan L, Hu X-m. Antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of various fractions of ethanol extract of Dianthus Superbus. Food Chemistry. 2007;104:1215–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valujskikh A, Pantenburg B, Heeger PS. Primed allospecific T cells prevent the effects of costimulatory blockade on prolonged cardiac allograft survival in mice. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(6):501–509. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Floyd TL, Koehn BH, Kitchens WH, Robertson JM, Cheeseman JA, Stempora L, et al. Limiting the amount and duration of antigen exposure during priming increases memory T cell requirement for costimulation during recall. J Immunol. 2011;186(4):2033–2041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chalasani G, Dai Z, Konieczny BT, Baddoura FK, Lakkis FG. Recall and propagation of allospecific memory T cells independent of secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6175–6180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092596999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demirkiran A, Hendrikx TK, Baan CC, van der Laan LJ. Impact of immunosuppressive drugs on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells: does in vitro evidence translate to the clinical setting? Transplantation. 2008;85(6):783–789. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318166910b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shevach EM, Davidson TS, Huter EN, Dipaolo RA, Andersson J. Role of TGF-Beta in the induction of Foxp3 expression and T regulatory cell function. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28(6):640–646. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kane LP, Weiss A. The PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway and T cell activation: pleiotropic pathways downstream of PIP3. Immunol Rev. 2003;192:7–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lalli PN, Strainic MG, Yang M, Lin F, Medof ME, Heeger PS. Locally produced C5a binds to T cell-expressed C5aR to enhance effector T-cell expansion by limiting antigen-induced apoptosis. Blood. 2008;112(5):1759–1766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crellin NK, Garcia RV, Levings MK. Altered activation of AKT is required for the suppressive function of human CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Blood. 2007;109(5):2014–2022. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patterson SJ, Han JM, Garcia R, Assi K, Gao T, O'Neill A, et al. Cutting edge: PHLPP regulates the development, function, and molecular signaling pathways of regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5533–5537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.