Abstract

Current antimalarial drug treatment does not effectively kill mature Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes, the parasite stage responsible for malaria transmission from human to human via a mosquito. Consequently, following standard therapy malaria can still be transmitted for over a week after the clearance of asexual parasites. A new generation of malaria drugs with gametocytocidal properties, or a gametocytocidal drug that could be used in combinational therapy with currently available antimalarials, is needed to control the spread of the disease and facilitate eradication efforts. We have developed a 1,536-well gametocyte viability assay for the high throughput screening of large compound collections to identify novel compounds with gametocytocidal activity. The signal-to-basal ratio and Z′-factor for this assay were 3.2-fold and 0.68, respectively. The IC50 value of epoxomicin, the positive control compound, was 1.42 ± 0.09 nM that is comparable to previously reported values. This miniaturized assay significantly reduces the number of gametocytes required for the alamarBlue viability assay, and enables high throughput screening for lead discovery efforts. Additionally, the screen does not require a specialized parasite line, gametocytes from any strain, including field isolates, can be tested. A pilot screen utilizing the commercially available LOPAC library, consisting of 1,280 known compounds, revealed two selective gametocytocidal compounds having 54 and 7.8-fold gametocytocidal selectivity in comparison to their cell cytotoxicity effect against the mammalian SH-SY5Y cell line.

Keywords: Malaria, gametocytes, alamarBlue, high throughput screening, malaria drug discovery

1. Introduction

Effective chemotherapy is a critical component of current antimalarial control efforts [1]. Consequently, recent reports of recrudescence and delayed clearance following the recommended course of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) are a major concern and being carefully monitored [2, 3]. The lack of alternatives to ACT has led to a number of small molecule and natural product library screens for the identification of new antimalarials [4–7]. However, none of the large scale screens (>100 compounds) have included the sexual stages of the parasite life cycle that are required for malaria transmission.

Sexual development begins in the red blood cell with the production of a single male or female gametocyte. Once taken up by a mosquito in a blood meal, gametocytes are triggered to emerge from the red blood cell (RBC), fertilize and begin sporogonic development [8]. In P. falciparum, the most virulent human malaria, gametocyte development takes 10–12 days and is resistant to most common antimalarials, except primaquine. [9]. This prolonged maturation allows the parasite to be transmitted for more than one week after the clearance of asexual parasites. The addition of primaquine to standard antimalarial therapy has been shown to block transmission of the parasite to the mosquitoes [10], but it has significant side effects in individuals with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency [11]. This toxicity has limited its widespread use and spurred the drive to identify alternatives with gametocytocidal activity.

Previous high throughput screens to identify anti-malaria drugs have utilized assays that assess DNA replication to monitor asexual growth and cannot be used to evaluate gametocytes, which do not proliferate. We have previously reported a viability assay that can be used to monitor gametocytocidal activity against any parasite line in a 96-well format. Recently several other groups have developed 96-well screens using parasite lines transformed with gametocyte-specific reporters [12, 13]. These assays were a marked improvement over the conventional method used to examine gametocytes, the manual quantitation of Giemsa-stained blood smears, which is very slow and labor intensive. However, all these assays continue to be limited to the analysis of 100s of compounds by the number of gametocytes that can be produced in vitro. In the work reported here, we describe the miniaturization of our gametocyte viability assay into a 1,536-well format that requires 25-fold fewer gametocytes/well than the previously reported 96-well format [14]. This assay format is conducive to high throughput screening, and has been validated using the library of pharmacologically active compounds (LOPAC) made up of 1,280 known compounds. Two active compounds with 54 and 7.8-fold gametocytocidal selectivity, in comparison to their cell cytotoxicity effect as observed against the human SH-SY5Y cell line, have been identified from this screen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

RPMI-1640 supplemented with L-Glutamine and 25 mM HEPES (Catalog No. CUS-0645) was purchased from K·D Medical Inc. (Columbia, MD). Gentamicin solution (Catalog No.15710-064), sodium bicarbonate solution (Catalog No. 25080), alamarBlue (Catalog No. DAL1100) and Opti-MEM reduced serum medium, no phenol red (Catalog No. 11058-021) were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). One liter of RPMI-1640 was supplemented with 11 μg/ml of gentamicin and 0.27% of sodium bicarbonate solutions to make incomplete media. O positive human blood and serum was obtained from Interstate Blood Bank, Inc. (Memphis, TN) and the 75-cm2 flasks (Catalog No. 430720) used for parasite culture were purchased from Corning Inc. (Corning, NY). The 1,536-well white sterile tissue culture treated polystyrene plates (Catalog No.789270-C) were purchased from Greiner Bio-One (Monroe, NC).

2.2. Gametocyte cell culture

P. falciparum 3D7 strain parasites were set up for gametocyte production in incomplete RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% positive human serum as described previously [15]. Stage III–V gametocytes were selected and enriched with 50 mM N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) and Percoll density gradient centrifugation, respectively. Briefly, asexual parasites were adjusted to 0.1% parasitemia and 6% hematocrit in 12.5 ml of complete media in a 75-cm2 flask on day 1. On day 3, 12.5 ml of complete media was exchanged and then 25 ml of complete media were exchanged every day from day 4 to 11. To eliminate asexual parasites, 2.8 ml of a 0.5 M NAG suspension was added to culture from day 9 to 11. On day 12 gametocytes were enriched with 65% Percoll/PBS by density gradient centrifugation at 1,860 × g for 10 min and maintained in 1.5 ml of complete media for compound library screening on day 13.

2.3. AlamarBlue assay optimization

All optimization and miniaturization experiments were performed in 1,536-well plate format. Malaria gametocytes, in suspension with 90% RBCs, were plated at a seeding density of 10 k, 20 k, and 27.5 k cells per well at a final volume of 5 μl per well using the Multidrop Combi (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Logan, UT). Cells were incubated for 72 hours at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. AlamarBlue dye was used for cell viability measurements. Briefly, 5 μl of a 2-fold concentrated alamarBlue solution (2 ml diluted in 8 ml of Opti-MEM media) was added per well, and plates were incubated for 4, 8, 10, and 24 hours at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. The fluorescence intensity of assay plates was captured using a fluorescence protocol (Ex= 525 nm, Em= 598 nm) on the ViewLux plate reader (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT). Table 1 outlines the finalized protocol used in the miniaturized gametocytocidal assay.

Table 1.

Gametocyte assay protocol (1,536-well plate)

| Step | Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medium | 2.5 μl/well | Incomplete growth medium |

| 2 | Compound | 0.02 μl/well | Compound in DMSO solution |

| 3 | Gametocytes | 2.5 μl/well | Suspension (8×106/ml) in incomplete growth medium with 20% human serum |

| 4 | Incubation | 72 hr | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 5 | Detection reagent | 5 μl/well | AlamarBlue (xx μM) in OPTI-MEM |

| 6 | Incubation | 24 hr | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 7 | Incubation | 120 min | Room temperature |

| 8 | Plate reading | Ex=525 nm Em=598 nm |

Fluorescence intensity |

2.4. Compound screen

Screening experiments were performed in a similar fashion as the optimization experiments. Briefly, 2.5 μl per well of incomplete medium was dispensed into 1,536-well plates using the Multidrop Combi. Compound libraries were transferred in a volume of 23 nl per well using the NX-TR Pintool (WAKO Scientific Solutions, San Diego, CA), and malaria gametocytes, in suspension with 90% RBCs and incomplete media supplemented with 20% human serum, were plated at a seeding density of 20 k cells per well and a volume of 2.5 μl per well using the Multidrop Combi. Plates were incubated for 72 hours at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. The alamarBlue dye was used for cell viability measurements, where 5 μl of a 2-fold concentrated alamarBlue solution (2 ml diluted in 8 ml of Opti-MEM media) was added per well, and plates were incubated for an additional 24 hours at 37 °C in the presence of 5 % CO2. Plates were read using a fluorescence protocol (Ex= 525 nm, Em= 598 nm) on the ViewLux plate reader.

2.5. Compound library and instruments for liquid handling

The library of pharmacologically active compounds (LOPAC) containing 1,280 compounds was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Compounds were dissolved in 100% DMSO as 10 mM stock solutions and were further diluted in 384 well plates to 7 concentrations at a 1:5 ratio followed by reformatting into 1,536-well compound plates. A CyBi®-Well dispensing station with a 384-well head (Cybio Inc., Woburn, MA) was used to reformat compounds in 384-well plate to 1,536-well plate. The 1 to 4 μl/well reagents were dispensed using the Multidrop Combi. Compounds in DMSO solution were transferred to 1,536-well assay plates at 23 nl/well using the Pintool workstation.

2.6. Data analysis

The 100% signal was defined from wells devoid of compounds, and the basal signal was obtained from wells treated with 17 nM epoxomicin. The primary screen data were analyzed using customized software developed by the NIH Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC) [16]. IC50 values of compounds in the confirmation experiments were calculated using the Prism software (Graphpad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA). Signal-to-background ratio was calculated as a comparison of signal in the presence or absence of the epoxomicin control compound. All values were expressed as the mean +/− SD (n=3).

3. Results

3.1. Assay miniaturization

Gametocyte yield in culture is a major limitation for compound screening, therefore assay miniaturization where the number of gametocytes per well is significantly reduced is essential for the high throughput screening of large compound collections. The production of mature gametocytes requires co-culturing with human RBCs for two weeks, with daily media changes, making it time and resource intensive. The median gametocyte yield of twelve 75-cm2 flasks was 2.40 × 108 mature gametocytes (the 25% and 75% percentile were 1.13 × 108 and 4.48 × 108, respectively, from 45 independent preparations). This number of gametocytes is sufficient for only 480 wells (equivalent to five 96-well plates) using the 96-well plate format gametocytocidal assay [14]. We have successfully miniaturized and optimized the gametocytocidal assay to 1,536-well format for the high throughput screening of large compound collections, where 2.40 × 108 gametocytes would be sufficient for 12,000 wells or seven 1,536-well plates. This is a striking 25-fold increase in the number of compounds that can potentially be tested.

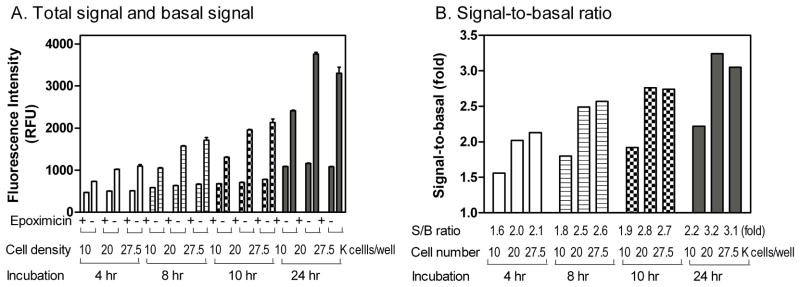

To establish the optimal gametocyte density for our miniaturized assay, we first tested seeding densities of 10,000, 20,000 and 27,500 gametocytes per well in a 1,536-well plate format. The gametocytes were plated in RPMI-1640 growth medium supplemented with red blood cells at 90% of the gametocyte count. The basal signal (100% killing) was defined by the treatment of gametocytes with 100 nM epoxomicin, a selective proteasome inhibitor used as a positive control compound, that has been previously reported to have potent gametocytocidal activity [17]. After the addition of alamarBlue to the assay plates, fluorescence intensity was measured at 4, 8, 10, and 24 hour time points (Fig. 1A). The signal-to-basal ratio for 20,000 gametocytes/well increased in comparison to that of 10,000 gametocytes/well, whereas the signal-to-basal ratio in 20,000 gametocytes/well did not differ significantly in comparison to that of 27,500 gametocytes/well. Additionally, the signal-to-basal ratio increased with an increase in alamarBlue dye incubation time for all three gametocyte seeding densities (Fig. 1B). Ultimately, a seeding density of 20,000 gametocytes/well, and the 24-hour alamarBlue incubation time resulted in a 3.2-fold window of signal-to-basal ratio, indicative of a robust assay window for high throughput screening, and were chosen as the optimal gametocyte seeding density and dye incubation time for our 1,536-well plate format gametocytocidal screen.

Fig. 1.

Effects of gametocyte seeding density and dye incubation time. (A) The fluorescence intensity of alamarBlue gametocyte assay increased with the seeding density from 10 k, 20 k, and 27.5 k gametocytes/well in 1,536-well plate format. The 100% gametocyte killing was defined by treatment with 100 nM epoxomicin. Plates were read at 4, 8, 10, and 24 hours after alamarBlue dye addition. (B) The signal-to-background (S/B) ratios calculated for different gametocyte seeding density and dye incubation time.

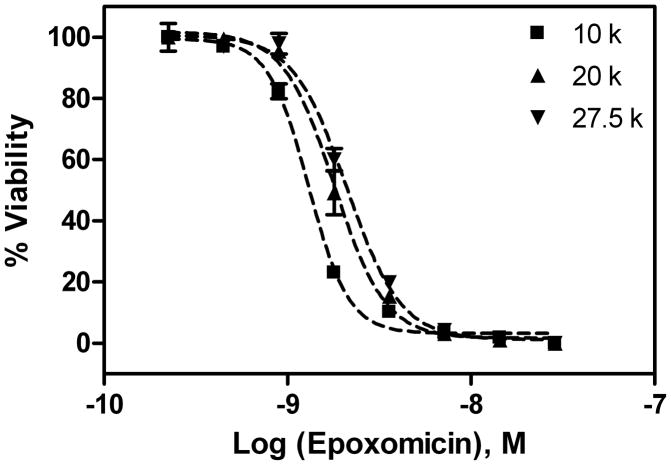

The IC50 values of epoxomicin against the seeding density of 10 k, 20 k and 27.5 k gametocytes/well were 1.3, 1.8 and 2.1 nM, respectively (Fig. 2), similar to the IC50 value of 2.16 nM reported in 96-well plate format [14]. The correlation of IC50 values of epoxomicin between the 96-well and 1,536-well plate formats, as well as previous morphologic and functional analysis by Giemsa stained smear and mosquito feed assay [17], further support that the gametocyte assay is amiable to miniaturization into 1,536-well plate format.

Fig. 2.

Effect of gametocyte density on the gametocyte screening assay in 1,536-well plate format. The IC50 values of epoxomicin at the gametocyte density of 10 k, 20 k, and 27.5 k cells/well were 1.3, 1.8 and 2.1 nM, respectively.

3.2. DMSO plate test

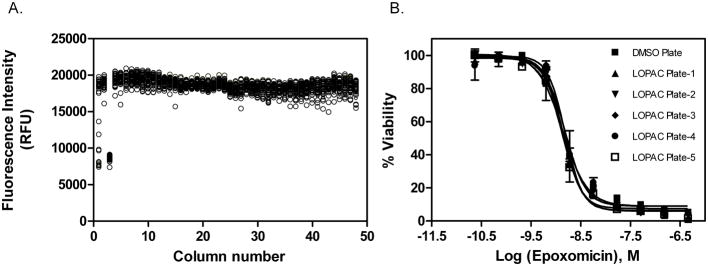

Because DMSO is used as a solvent for all compounds in our compound libraries, initially a DMSO plate was tested in the 1,536-well plate format gametocyte assay to assess stability and robustness. Using a pintool workstation, 23 nl of 100% DMSO solution was added to the assay plate for a final DMSO concentration of 0.46%. Results of the DMSO plate screening are illustrated in a scatter plot (Fig. 3A). The Z′-factor was 0.68, indicative of a robust assay suitable for high throughput screening.

Fig. 3.

Results of a DMSO plate screen test for the gametocyte assay in 1,536-well plates, where column 1 in the plate contains epoxomicin titration (1:3 dilution series used ranging from 460-0 nM), column 3 contains epoxomicin at 17 nM, and columns 2,4–48 contain 0.5% DMSO. (A) Scatter plot representation of the DMSO screen plate. The S/B ratio, CV, and Z′ factor were 2.2-fold, 4.4%, and 0.68, respectively. (B) Concentration-response curves of epoxomicin determined in all the assay plates that was used as an internal control.

3.3. LOPAC library screening

The LOPAC library is commonly used as a screening validation tool for hit rate estimation and overall assay performance. Because of the low yield associated with gametocyte culturing, we chose to perform a single point screen of the LOPAC library at a concentration of 1.8 μMin duplicate. A titration of epoxomicin was included in every assay plate as a positive control. The average IC50 value of epoxomicin for all plates tested was 1.42 ± 0.09 nM (Fig. 3B), indicative of consistent activity for control compound across all assay plates. Using a hit selection criteria of ≥ 75% inhibition response with respect to the epoxomicin control, 7 compounds were identified from the primary screen as hits (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of confirmed gametocytocidal compounds from the LOPAC library screen

| Compound name | Compound ID | Reported property | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dibenziodolium | NCGC00015334 | inhibitor of nitric oxide synthetase and NADPH oxidase | 0.17 |

| Antabuse | NCGC00016000 | aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor | 0.25 |

| CyPPA | NCGC00186022 | activator of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels | 1.17 |

| Calcimycin | NCGC00025064 | antibiotic, a calcium ionophore | 1.96 |

| Phenanthroline | NCGC00013043 | metalloprotease inhibitor | 2.19 |

| Clotrimazole | NCGC00015251 | antifungal by inhibiting biosynthesis of the sterol ergostol | 2.44 |

| Cyclosporine | NCGC00093704 | immunosuppressant, protein synthesis inhibitor | 7.12 |

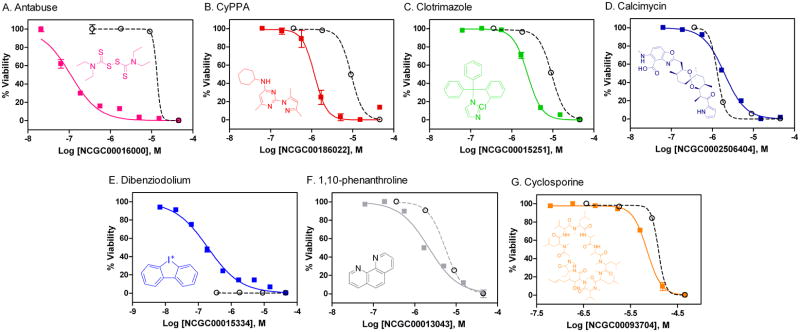

3.4. Hit confirmation

All seven primary hits were selected and tested in an 11 point 1:3 dilution series, ranging from 1 nM to 50 μM for the confirmation experiment. The gametocytocidal activity for all 7 compounds was confirmed using the alamarBlue assay in the 1,536-well plate format (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of these compounds against the human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line was evaluated (Fig. 4). Two of the inhibitors evaluated, Antabuse, and Cyclohexyl-[2-(3,5-dimethyl-pyrazol-1-yl)-6-methyl-pyrimidin-4-yl]-amine (CyPPA)exhibited approximately greater than 50 and 7.5 -fold potency towards gametocytes, respectivelyin comparison to their cytotoxic effect in the SH-SY5Y cell line.

Fig. 4.

Summary of the confirmed compounds from LOPAC library screen. The dose response curves are shown for the indicated compound tested against gametocytes (solid line) and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (dashed line): (A) Antabuse (NCGC00016000) resulted in IC50 values of 0.25 μM and 13.4 μM for the gametocyte assay and cytotoxicity assay, respectively. (B) CyPPA (NCGC00186022) resulted in IC50 values of 1.17 μM and 9.16 μM for the gametocyte assay and cytotoxicity assay, respectively. (C) Clotrimazole (NCGC00015251) resulted in IC50 values of 2.44 μM and 9.48 μM for the gametocyte assay and cytotoxicity assay, respectively. (D) Calcimycin (NCGC00025064) resulted in IC50values of 1.96 μM and 1.37 μM for the gametocyte assay and cytotoxicity assay, respectively. (E) Dibenziodolium (NCGC00015334) resulted in an IC50of 0.17μM for the gametocyte assay and was completely cytotoxic in the lowest compound concentration (0.37μM ) testedin the cytotoxicity assay. (F) 1,10-phenanthroline (NCGC00013043) resulted in IC50values of 2.19 μM and 5.45 μM for the gametocyte assay and cytotoxicity assay, respectively. (G) Cyclosporine (NCGC00093704) resulted in IC50values of 7.12 μM and 12.4 μM for the gametocyte assay and cytotoxicity assay, respectively.

4. Discussion

The miniaturized and optimized 1,536-well plate format gametocytocidal assay described here reduces the number of gametocytes required per well by 25-fold, making the assay amiable to high throughput screening. Our results demonstrated that 20,000 gametocytes/well in a 1,536-well plate format produced comparable screening results to those obtained in the 96-well plate format of the alamarBlue gametocytocidal assay. The S/B ratio and Z′-factor were 3.2-fold and 0.68, respectively, for our 1536-well miniaturized assay, as opposed to a S/B ratio and Z′-factor of 3.0-fold and 0.94, respectively, for the 96-well assay format under similar conditions. These results further confirmed that the 1,536-well plate format is suitable for high throughput screening. In addition to the robustness of this assay, the reproducibility of compound potency was verified by the consistent IC50 values for epoxomicin determined in different experiments. Together, the results suggest that a large compound library can be screened in batch-execution mode, where a portion of the large library is screened in accordance with gametocyte yield.

The propagation of large numbers of gametocytes is a laborious and resource intensive process. Factors that contribute to its difficulty include the need to co-culture with red blood cells and replenish the culture medium daily through the 14-day developmental process. The previously reported 96-well plate format alamarBlue gametocytocidal assay requires 500,000 gametocytes/well, which is equivalent to 4.8 × 107 gametocytes per plate. Consequently, to screen a median library of 500,000 compounds that is typically used in lead discovery a total of 3.3 × 1011 gametocytes would be required for screening in 96-well plate format at a single concentration (20% additional reagent has been included to accommodate for dead volume). Based on the median yield per flask, the production of 3.3 × 1011 gametocytes would require an estimated 16,500 75-cm2 flasks and 3.7 × 106 liters of complete media. In contrast to the 96-well plate format, a total of 1.34 × 1010 gametocytes prepared from 670 75-cm2 flasks and 1.5 × 105 liters of complete media are required to screen 500,000 compounds at a single concentration in our 1,536-well plate assay. This is a 25-fold reduction in the total number of gametocytes and complete media. Thus, the miniaturization of the gametocyte viability assay translates to a significant savings in resource and reagents, allowing for the high throughput screening of larger compound libraries.

The signal-to-basal ratio of our miniaturized 1,536-well plate gametocyte assay is 3.2-fold, typical of what is observed in alamarBlue cytotoxicity assays [18]. A previous study demonstrated that there is a 20-fold reduction in signal for RBC’s in comparison to gametocytes in the alamarBlue assay [14], eliminating the need to remove RBCs from the gametocyte assay. Nevertheless, it is challenging to increase the signal-to-basal ratio in the alamarBlue assay, because the dye itself has a high fluorescence background. We attempted to develop a luciferase based ATP content assay to measure gametocyte viability, but it failed to generate a robust signal-to-basal ratio due to the presence of RBCs, which are required for culturing and enhancing the uniform distribution of the parasites (data not shown). Three other assays in 96-well plate format have been reported for the evaluation of gametocytocidal activity and two of these used transformed cell lines [12, 13, 19]. In one method the GFP-positive gametocyte-infected RBCs were isolated using a cell sorter before the measurement of ATP levels [13], while in another the cells where first purified by gradient centrifugation and then by magnetic column to remove uninfected RBCs. This extensive purification is required to remove background signal from uninfected RBCs, but also significantly decreases gametocyte yield and increases the processing time. The third approach is limited to the use of a parasite line transformed with a luciferase reporter to monitor gametocyte viability and the associated signal variation limited their ability to accurately quantitate compound potency and determine IC50 [12].

In comparison with the human SH-SY5Y cell cytotoxicity assay, two of the seven confirmation compounds, Antabuse and CyPPA, exhibited approximately 54 and 7.8-fold potency towards gametocytes, respectively. Briefly, CyPPA (NCGC00186022) is an activator of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels; selective for the SK3 and SK2 subtypes, and Antabuse (NCGC00016000) is an aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor. Antabuse has previously been reported to inhibit the asexual growth of P. falciparum suggesting a common essential pathway that could be targeted to design a drug that blocks both clinical disease and transmission [22, 23]. An effect of CyPPA on P. falciparum has not been previously reported and could represent a new target. The remaining five compounds have less than 10-fold selectivity against gametocytes in comparison with SH-SY5Y cells. Briefly, Clotrimazole (NCGC00015251) is an imidazole derivative with broad spectrum antimycotic activity and acts by inhibiting the biosynthesis of the sterol ergostol (an important component of fungal cell membrane) [20, 21], Dibenziodolium (NCGC00015334) is potent inhibitor of nitric oxide synthetase and NADPH oxidase, and Calcimycin (NCGC00025064) is a polyether antibiotic from Streptomyces chartreusensis and an ionophorous compound. 1,10-phenanthroline (NCGC00013043) is a metalloprotease inhibitor, while Cyclosporine (NCGC00093704) is an immunosuppressor, and is typically used as a broad protein synthesis inhibitor.

In conclusion, an alamarBlue gametocyte assay has been developed in 1,536-well plate format for high throughput screening to identify gametocytocidal compounds. The miniaturized assay format dramatically reduced the total number of gametocytes and reagents required for the screening of large compound collections, while maintaining assay sensitivity for compound potency quantification, a task not feasible with previously reported assay formats. The accumulative results obtained, a signal-to-basal ratio of 3.2-fold, Z′-factor value of 0.68, and consistent IC50 values of the control compound epoxomicin, demonstrate the robustness and reproducibility of this miniaturized gametocyte assay. The pilot LOPAC screen revealed two gametocytocidal compounds that have 54 and 7.8-fold selectivity, respectively, in comparison to their cytotoxicity as observed in human SH-SY5Y cells. The further screening of a large compound library using this assay will enable identification of new lead compounds for the development of gametocytocidal drugs.

Highlights.

Developed a 1536-well plate viability assay for screening gametocytocidal compounds

Identified 7 gametocytocidal compounds from a screen of 1,280 known compounds

3 compounds had >10 fold selectivity to gametocytes compared to a human cell line

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases (TRND), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and Public Health Service grant AI10139601 from the NIAID, National Institutes of Health (NIH). The authors thank Paul Shinn for assistance in compound management. TQT is a JSPS Research Fellow in Biomedical and Behavioral Research at NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Trape JF. The public health impact of chloroquine resistance in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:12–7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrara VI, Zwang J, Ashley EA, Price RN, Stepniewska K, Barends M, et al. Changes in the treatment responses to artesunate-mefloquine on the northwestern border of Thailand during 13 years of continuous deployment. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witkowski B, Iriart X, Soh PN, Menard S, Alvarez M, Naneix-Laroche V, et al. pfmdr1 amplification associated with clinical resistance to mefloquine in West Africa: implications for efficacy of artemisinin combination therapies. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3797–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01057-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL, et al. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature. 2010;465:305–10. doi: 10.1038/nature09107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guiguemde WA, Shelat AA, Bouck D, Duffy S, Crowther GJ, Davis PH, et al. Chemical genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2010;465:311–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato N, Sakata T, Breton G, Le Roch KG, Nagle A, Andersen C, et al. Gene expression signatures and small-molecule compounds link a protein kinase to Plasmodium falciparum motility. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:347–56. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plouffe D, Brinker A, McNamara C, Henson K, Kato N, Kuhen K, et al. In silico activity profiling reveals the mechanism of action of antimalarials discovered in a high-throughput screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9059–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alano P, Carter R. Sexual differentiation in malaria parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:429–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit-Vical F, Lelievre J, Berry A, Deymier C, Dechy-Cabaret O, Cazelles J, et al. Trioxaquines are new antimalarial agents active on all erythrocytic forms, including gametocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1463–72. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00967-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smithuis F, Kyaw MK, Phe O, Win T, Aung PP, Oo AP, et al. Effectiveness of five artemisinin combination regimens with or without primaquine in uncomplicated falciparum malaria: an open-label randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:673–81. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70187-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baird JK, Surjadjaja C. Consideration of ethics in primaquine therapy against malaria transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adjalley SH, Johnston GL, Li T, Eastman RT, Ekland EH, Eappen AG, et al. Quantitative assessment of Plasmodium falciparum sexual development reveals potent transmission-blocking activity by methylene blue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1214–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112037108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peatey CL, Leroy D, Gardiner DL, Trenholme KR. Anti-malarial drugs: how effective are they against Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes? Malar J. 2012;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka TQ, Williamson KC. A malaria gametocytocidal assay using oxidoreduction indicator, alamarBlue. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011;177:160–3. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ifediba T, Vanderberg JP. Complete in vitro maturation of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. Nature. 1981;294:364–6. doi: 10.1038/294364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Jadhav A, Southal N, Huang R, Nguyen DT. A grid algorithm for high throughput fitting of dose-response curve data. Curr Chem Genomics. 2010;4:57–66. doi: 10.2174/1875397301004010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czesny B, Goshu S, Cook JL, Williamson KC. The proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin has potent Plasmodium falciparum gametocytocidal activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4080–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00088-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sykes ML, Avery VM. Development of an Alamar Blue viability assay in 384-well format for high throughput whole cell screening of Trypanosoma brucei brucei bloodstream form strain 427. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:665–74. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lelievre J, Almela MJ, Lozano S, Miguel C, Franco V, Leroy D, et al. Activity of clinically relevant antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes in an ATP bioluminescence “transmission blocking” assay. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saliba KJ, Kirk K. Clotrimazole inhibits the growth of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:666–7. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiffert T, Ginsburg H, Krugliak M, Elford BC, Lew VL. Potent antimalarial activity of clotrimazole in in vitro cultures of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:331–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deharo E, Barkan D, Krugliak M, Golenser J, Ginsburg H. Potentiation of the antimalarial action of chloroquine in rodent malaria by drugs known to reduce cellular glutathione levels. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:809–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheibel LW, Adler A, Trager W. Tetraethylthiuram disulfide (Antabuse) inhibits the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:5303–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]