Abstract

Between 50–80% of patients with schizophrenia do not believe they have any illness and self assessment of cognitive impairments and functional abilities is also impaired compared to other information, including informant reports and scores on performance-based ability measures. The present paper explores self- assessment accuracy in reference to real world functioning as measured by milestone achievement such as employment and independent living. Our sample included 195 people with schizophrenia examined with a performance-based assessment of neurocognitive abilities and functional capacity. We compared patient self-assessments across achievement of milestones, using patient performance on cognitive and functional capacity measures as a reference point. Performance on measures of functional capacity and cognition was better in people who had achieved employment and residential milestones. Patients with current employment and independence in residence rated themselves as more capable than those who were currently unemployed or not independent. However, individuals who had never had a job rated themselves as at least as capable as those who had been previously employed. These data suggest that lifetime failure to achieve functional milestones is associated with overestimation of abilities. As many patients with schizophrenia never achieve milestones, their self-assessment may be overly optimistic as a result

Keywords: Cognition, insight, disability, functional capacity

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is an illness characterized by four domains of dysfunction: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, and affective symptoms. These four domains have been found to predict deficits in psychosocial and occupational functioning in schizophrenia (Bowie et al., 2008). Studies have suggested that negative symptoms have a greater impact on real-world functioning than other symptoms (Rabinowitz et al., 2012) and that depression is associated with impairments in the performance of everyday functional skills independent from the influence of cognition and functional capacity (Sabbag et al., 2012). Patients with schizophrenia have been shown to lack awareness of impairments associated with illness in several areas, including symptoms (Amador et, al., 1994), cognitive abilities (Medalia and Thysen, 2008), functional capacity (Sabbag et al., 2011), and everyday functioning (Bowie et al., 2007), largely through a tendency to underestimate the significance and severity of symptoms and to overestimate their functional abilities and current everyday functioning.

Poor insight is a core feature of schizophrenia and includes reduced awareness of having a mental disorder, the need for treatment, understanding the consequences of the illness and the attribution of symptoms to the disorder. Between 50–80% of patients with schizophrenia do not believe they have any illness or impairments (Amador and Gorman, 1998). There are multiple strategies previously employed for assessing real-world functioning and its correlates, including rating scales completed by informants and patients (Leifker et al., 2011), direct observations by trained clinicians (Kleinman et al., 2009), and performance-based measures aimed at the ability to perform critical everyday skills (Harvey et al., 2007). Studies have shown that self-reports of cognition and everyday functioning in schizophrenia often do not converge with objective evidence, obtained both from performance-based assessments (Bowie et al., 2007; Keefe et al. 2006; Sabbag et al., 2012) or the reports of other evaluators (Keefe et al., 2006; McKibbin et al., 2004; Sabbag et al., 2011). Studies have shown that unawareness of cognitive deficits (Medalia and Thysen, 2008; 2010) is also common. In a recent investigation, we (Sabbag et al., 2011), found that the clinician ratings of the severity of real-world impairment were more strongly correlated with performance-based data relevant to outcomes than impairment ratings generated by friends, relatives, or the patients themselves, suggesting that the characteristics of the specific observer is important as well.

Impaired accuracy of self-assessment is not limited to persons with severe mental illness. The accuracy of self-assessment in both clinical populations and healthy individuals appears to be limited. Healthy individuals tend to consistently overestimate their abilities, with poor performers having a particularly positive bias (Dunning and Story, 1991; Ehrlinger et al., 2008). In contrast, otherwise healthy individuals with mild depressive symptoms tend to be more accurate in their self- assessments (Alloy and Abramson, 1979), with moderate to severe depression associated with underestimation of functioning (Bowie et al., 2007). Recently, we (Sabbag et al., 2012) found that higher levels of depressive symptoms within the moderate ranges in people with schizophrenia were associated with less overestimation of everyday functioning. Clinical ratings of delusions, suspiciousness, grandiosity and poor rapport predicted over- estimation of self-reported functioning compared to interviewer judgments. Such findings mirror those from studies of people with neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions, including bipolar disorder (Burdick et al., 2005), multiple sclerosis (Carone et al., 2005), and traumatic brain injury (Spikman and van der Naalt, 2010). Across all conditions, individuals with poorer neuropsychological (NP) test performance tend to underestimate their impairment.

Everyday functioning can be defined in several ways. The rating scales typically rate the level of success in performance of various skilled acts, such as cleaning, cooking, or financial management. Many of these rating scales do not have items that directly assess milestone achievements, such as marriage and financial responsibility for maintenance of a residence (Harvey et al., 2012). Milestone achievement can be defined across numerous domains. Living without supervision, being financially responsible, obtaining competitive employment, or having a stable relationship comparable to marriage signifies successful outcome. Such milestones have long been an integral part of clinical assessments and conceptions of recovery in severe mental illness (Harvey & Bellack, 2009), but have less often been systematically analyzed in the course of research on real world functioning. In patients with schizophrenia, milestone achievement rates are typically low, particularly when achievement of more than one milestone is examined (Harvey et al., 2012). However, given the relative ease of validly measuring milestones (both their lifetime achievement and sustained maintenance) and their clear validity, when achieved, as indices of successful real world functioning, it is important to evaluate what distinguishes milestone achievers from their peers who do not achieve these milestones on a lifelong or current basis.

We have previously shown, in the current sample (Harvey et al., 2011) and in previous studies with other samples (Bowie et al., 2008; 2010; Mausbach, Bowie et al 2007; Mausbach, Harvey et al 2007; Mausbach et al., 2011) that performance on neuropsychological tests and measures of functional capacity were correlated with both ratings on functional status rating scales and achievement of functional milestones in residential and vocational domains. These data suggest that real-world functional outcomes, assessed with rating scales and indexed by achievement of milestones, have determinants in ability variables as well as environmental and social factors (Rosenheck et al., 2006)

Achieving specific milestones themself may have the potential to impact on accuracy of self-assessment, in that individuals who have had a job in the past or live independently have experience with the demands and challenges associated with achieving these goals (Bryson et al., 2002). Milestone achievers may have information that allows them to be more realistic with respect to self-assessment of their abilities. The current paper expands our research on the accuracy of self-assessment in patients with schizophrenia to the association of self-assessment with milestone achievement, using data from the results of the VALERO study phase 1 (Leifker et al., 2011). In this study, the achievement of functional milestones in domains of residential functioning, social outcomes and productive activities was examined, with a goal of examining the association between achievement of milestones and of self-assessment of real world everyday functioning. We compared patients who had and had not achieved functional milestones on their self-assessments of their everyday functioning on two different everyday functioning rating scales: the Specific Levels of Functioning (SLOF; Schneider and Stuening, 1983) and the Quality of Life Scale (QLS; Heinrichs et al., 1994). Interviewer ratings on subscales were previously shown to be related to milestone achievement in specific functional domains (Harvey et al., 2012). We then used performance on neuropsychological tests and performance-based measures of functional capacity to further compare patients who had and had not achieved milestones, in order to provide an objective reference point for the self-reported levels of competence of the patients.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Study participants were patients with schizophrenia who were receiving treatment at one of three different outpatient service delivery systems, two in Atlanta and one in San Diego. All research participants provided signed, informed consent, and this research study was approved by local IRBs. In Atlanta, patients were either recruited at an intensive psychiatric rehabilitation program (Skyland Trail) or from the general outpatient population of the Atlanta VA Medical Center. The San Diego patients were recruited from the UCSD Outpatient Psychiatric Services clinic, which is a large public mental health clinic, from other local community clinics, and by word of mouth.

All patients with schizophrenia were administered either the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1995: Atlanta sites) or the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998: San Diego) by a trained interviewer. All diagnoses were subjected to a consensus procedure at the local site. Patients were excluded for a history of traumatic brain injury with unconsciousness >10 minutes, brain disease such as seizure disorder or neurodegenerative condition, or the presence of another DSM-IV-TR diagnosis that would exclude the diagnosis of schizophrenia. None of the patients were experiencing their first psychotic episode. Substance abuse was not an exclusion criterion, in order to capture a broad array of patients, but patients who appeared intoxicated were rescheduled. Inpatients were not recruited, but patients resided in a wide array of unsupported, supported, or supervised residential locations. Descriptive information on patients has been previously presented and is contained in online supplemental material (See supplemental table 1).

2.2 Procedure

All patients were examined with a performance-based assessment of neurocognitive abilities and functional capacity which has been reported on previously (Harvey et al., 2011). They also provided self-reports of social, residential, and vocational functioning on six different functional outcome scales, which were either administered to them as interviews by a trained rater or completed in a questionnaire format, depending on the instructions of the scales. Patients received $50.00 for their time and effort.

2.2.1 Real-World Functional Outcomes

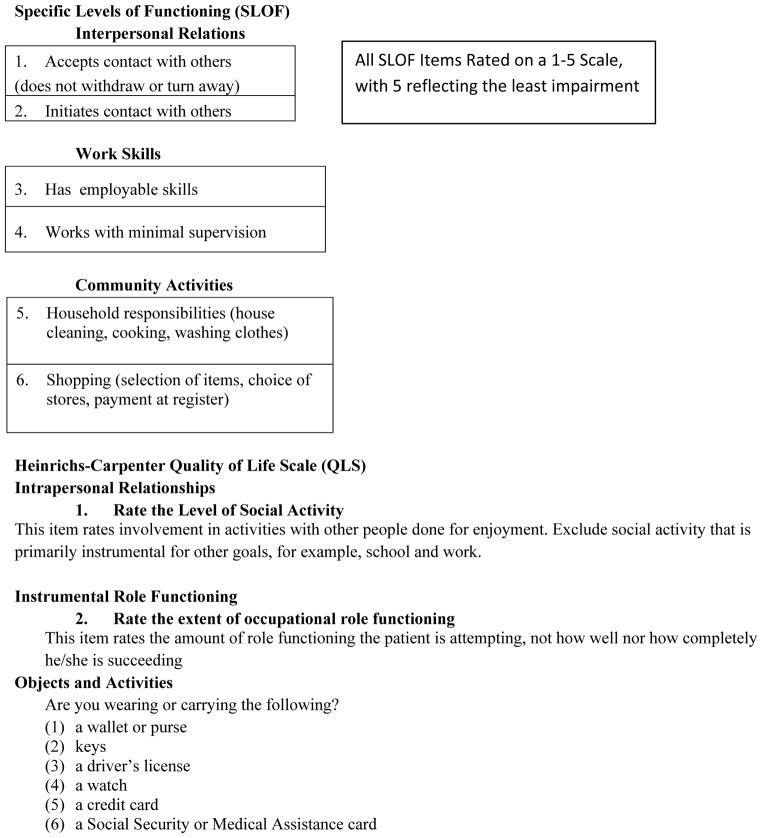

The initial phase of the VALERO study included a RAND panel that selected 6 functional outcome scales from a much larger group of candidate scales, as most suitable for current use at the time of the panel (see Leifker et al., 2011 for detailed descriptions of these instruments). Two of these scales, the QLS and the SLOF, had subscales directly targeted at the domains of functioning in which we were interested: vocational, social, and everyday living skills; they are the focus of this report. These instruments were modified by deletion of some of their subscales following the suggestions of the RAND panel. The social acceptability and personal care subscales of the SLOF were excluded because of reduced relevance and potential ceiling effects and for the QLS the intrapsychic foundations subscale was not included in the analyses of the data because it measures deficit (i.e., negative symptoms). The SLOF subscales that we examined were interpersonal relations, work skills, and everyday activities. The QLS subscales were intrapersonal relationships, instrumental role functioning, and objects and activities. See Table 1 for sample items from each subscale for each rating scale.

Table 1.

Sample Items from the Functional Status Rating Scales

|

2.2.2 Functional Milestone Achievements

We collected information from patients, informants, and medical records on the achievement of various functional milestones. In cases of uncertainty, a consensus was obtained through discussion with the local principal investigator and the interviewer. We recorded details about achievements (e.g., first job, most recent job, best job) in order to increase accuracy of reporting. These milestones included social outcomes such as marriage or an equivalent long-term relationship. For employment, we collected current and lifetime history of supported or competitively obtained employment (either part or full time), regardless of duration or reason for termination. For residential status, we determined whether the individuals were currently living without supervision and whether they were financially responsible for their housing (even if they used disability compensation to pay their bills) using the methods we previously employed (Harvey et al., 2012). These two residential outcomes were examined separately because they are not necessarily overlapping.

2.2.3 Performance-Based Ability Assessments

2.2.3.1 Neurocognition

We examined cognitive performance with a modified version of the MATRICS consensus cognitive battery (MCCB, Nuechterlein et al., 2008). For this study, we did not include the social cognition measure, from the MCCB, the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test Managing Emotions, because two separate meta-analyses (Fett et al., 2011 and Ventura et al., in press) demonstrated that social cognition has a clearly different relationship with real-world outcomes in than neurocognition. We calculated a composite score, an average of 9 age-corrected t-scores based on the MCCB normative program, as our critical dependent variable.

2.2.3.2 Functional Capacity

We administered the Brief version of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B Mausbach, Harvey, et al., 2007). The UPSA-B is a measure of functional capacity in which patients are asked to perform everyday tasks related to communication and finances. During the Communication subtest, participants role-play exercises using an unplugged telephone (e.g., emergency call; dialing a number from memory; calling to reschedule a doctor’s appointment). For the Finance subtest, participants count change, read a utility bill, and write and record a check for the bill. The UPSA-B requires approximately 10–15 minutes, and raw scores are converted into a total score ranging from 0–100, with higher scores indicating better functional capacity.

2.3 Data Analyses

We dichotomized the three different domains of functional milestones, separating the patients into those who had achieved a long-term relationship or not, were currently employed or not, were ever employed or not, were currently living independently or not, and were financially responsible for their dwelling or not. We compared patients who had and had not achieved functional milestones on the specific SLOF and QLS subscales aimed at that functional domain with t-tests (using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). Finally, we compared performance on the modified MCCB and the UPSA-B across the groups who differed in their milestone achievements as well.

In our previous study (Harvey et al., 2012), we found that milestone achievements were consistently associated with subscale scores in the same domains and that global scores did not predict milestones; there was also no cross-over prediction across domains (ratings of vocational functioning did not predict social or residential outcomes, etc.). Thus, for the sake of clarity and parsimony, we present the comparisons of self-assessments across levels of achievement on only those scales previously found to be associated with achievement of functional milestones.

3. Results

We first compared patients who had and had not achieved each of the 5 functional milestones (ever married, ever employed, currently employed, currently living independently, and currently financially responsible) on age and educational attainment. Of the 10 t-tests, only one was significant, in that patients who had been previously married were older than those who had not (m=48.1, sd=8.6 vs. 40.6, SD= 12.8), t(194)=4.57, p<.001. We also correlated PANSS total, negative, and positive subscale scores with the 6 self-report functional outcomes measures with Pearson correlations. Of the 18 total correlations, 4 were significant at a level that would have exceeded Bonferroni criteria (p<.001). All involved self-reported social functioning and in every case, more severe symptoms were correlated with reduced levels of self-reported social deficit.

Table 2 provides means and standard deviations on the SLOF and QLS subscales tapping social functioning for patients who achieved the milestone of marriage or equivalent and for those who did not. There were no differences in self-assessed social functioning between those patients who had and had not ever experienced a long term relationship; consistent with considerable recent research (Bowie et al., 2007; Leifker et al., 2009), there were no differences in neurocognition or functional capacity either. Table 3 provides means and standard deviations on the SLOF and QLS subscales aimed at vocational functioning and the results of analyses comparing patients who have the milestones of current or previous employment and those who did not. As can be seen in the table, both UPSA and MCCB scores were higher for patients who had achieved either current or lifetime employment. However, patients who had never been employed rated themselves as significant more capable on the QLS instrumental role subscale than those who had had a job at some time in their lives. For the other two functional subscales, there was no difference in self-reported vocational ability between those who had and had not ever had a job. In contract, currently employed patients rated themselves as more capable than those who were not currently employed across all three relevant functional status subscales.

Table 2.

Self Assessment of Social Functioning as a Function of Milestone Achievement

| Ever Married | No (N=90) | Yes (N=105) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| SLOF Interpersonal Relations | 25.69 | 5.90 | 25.26 | 6.34 | 0.48 | .63 |

| QLS Intrapersonal Relations | 25.34 | 11.76 | 26.80 | 11.16 | 0.82 | .41 |

| MCCB Composite | 38.30 | 7.09 | 37.57 | 6.94 | 0.71 | .48 |

| UPSA-B Total score | 75.16 | 14.10 | 77.94 | 11.73 | 1.45 | .15 |

Table 3.

Self Assessment of Vocational Functioning as a Function of Milestone Achievement

| Ever Employed | No (N=33) | Yes (N=162) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| SLOF Work Skills | 24.69 | 5.66 | 23.68 | 4.51 | 1.03 | .31 |

| QLS Instrumental Role | 16.32 | 4.23 | 12.57 | 5.45 | 2.69 | .009 |

| QLS Objects and Activities | 7.82 | 1.78 | 8.23 | 1.84 | 1.00 | .32 |

| MCCB Composite | 34.31 | 7.41 | 41.67 | 6.96 | 4.96 | .001 |

| UPSA-B Total Score | 74.14 | 13.16 | 79.45 | 13.48 | 3.01 | .007 |

| Currently Employed | No (N =171) | Yes (N=24) | t | p | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| SLOF Work Skills | 23.51 | 4.70 | 26.65 | 3.41 | 3.27 | .001 |

| QLS Instrumental Role | 12.56 | 5.41 | 16.63 | 3.93 | 3.32 | .001 |

| QLS Objects and Activities | 7.80 | 1.87 | 8.58 | 1.77 | 2.07 | .046 |

| MCCB Composite | 37.58 | 7.04 | 39.98 | 5.92 | 2.66 | .005 |

| UPSA-B Total Score | 75.99 | 13.39 | 81.11 | 10.56 | 2.16 | .037 |

Finally, as seen in Table 4, individuals who were currently either financially responsible or living independently had higher scores on both self-assessed functional abilities and on performance-based measures of ability. Thus, current residential functioning status, defined in terms of both independence and financial responsibility, was associated with self -reports of both functioning and ability scores that were higher than those seen in individuals not living independently or being financially responsible.

4. Discussion

The data presented in this paper make several points regarding self-assessment of functioning in people with schizophrenia. When asked to self-report their functional abilities, patients with current functional achievement in residential and vocational domains rate themselves as more capable in the immediately relevant functional areas than those individuals who were not succeeding in those domains. These reports of better functional skill were corroborated by better performance on tests of neurocognition and functional capacity. However, patients who had never been employed rated themselves as more (or equivalently) capable in vocational skills than those who had been employed in the past or the present. These data suggest that the experience of work, with its associated challenges and demands, may lead to beneficial modification of opinions regarding functional abilities. An additional possibility, consistent with previous research, is that the experience of work itself may in fact lead to improvements in everyday functioning (Bryson et al., 2002). Studies of the maintenance of cognitive remediation suggests that employment is sustained long after the end of cognitive remediation, suggesting that work may be sustained cognitive benefits (McGurk et al., 2007). The results also suggest that the current achievement is correlated with assessments of current functional abilities that are more accurate than assessments of lifetime achievement. Further, previous findings of globally inaccurate self-assessment of functioning may be related to the fact that these assessments were performed on a global basis, collapsing across different functional domains.

There are limitations in this dataset that require explanation. First, the sample was not selected on the basis of milestone achievements and the rates of achievement of these milestones may not be representative of the population of people with schizophrenia. Rates of current employment are consistent with other research, but the rate of marriage and independence in residence may be slightly higher than the general population of people with schizophrenia. Also, we did not measure other abilities, such as social cognition, that may be relevant to some of our milestones, particularly social outcomes (Fett et al., 2011; Ventura et al., in press).

While the differences across milestone achievement in the performance-based measures were statistically significant, the effect sizes were moderate or smaller. Thus, there is likely to be considerable overlap in performance on ability measures across patients who have and have not achieved functional milestones. This is consistent with the larger research literature indicating that environmental factors such as disability compensation, opportunities, and the expense associated with maintenance of a residence have a notable impact on achievement in people with schizophrenia (Rosenheck et al., 2006).

Achievement of relationship milestones was unassociated with performance on NP and FC measures, as well as self-reports of social abilities. It is possible that these achievements are related to other abilities, such as social cognition (See Harvey and Penn, 2010 for a discussion). Also, the current rating scales do not specifically assess achievement of milestones such as marriage, which is a clear shortcoming. Their focus is more on the intermediate achievements such as socializing, conversing, and participating in group social activities.

In summary, these results suggest that there are circumstances where self-report of abilities on the part of people with schizophrenia is generally accurate. At the same time, this accuracy in self-assessment is present in cases with current milestone achievements and better scores on performance-based variables. As achievement of current work was quite rare in the sample (as in schizophrenia patients in general; McGurk and Mueser, in press), the majority of patients are actually providing inaccurate reports of their abilities. Patients who were never employed report that they have better work skills than people who have been employed in the past (and equivalent to the reports of currently employed patients). For people with schizophrenia who have never achieved specific functional milestones, performance-based assessment of skills seems more likely to yield a valid result than asking for self-reports of how capable they are.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Self Assessment of Residential Functioning as a Function of Milestone Achievement

| Currently Independent | No (N=76) | Yes (N=119) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| SLOF Everyday Activities | 50.22 | 4.19 | 52.13 | (5.84) | 2.80 | .006 |

| QLS Objects and Activities | 7.22 | 1.66 | 8.36 | (1.79) | 4.62 | .001 |

| QLS Instrumental Role | 11.53 | 5.31 | 16.18 | (4.85) | 4.09 | .001 |

| MCCB Composite | 35.20 | 7.06 | 39.32 | (6.86) | 4.00 | .001 |

| UPSA-B Total Score | 70.93 | 13.36 | 81.11 | (13.05) | 5.66 | .001 |

| Financially Responsible | No (N | = 109) | Yes (N | = 86) | t | p |

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| SLOF Everyday Activities | 50.58 | 5.35 | 52. 72 | 5. 34 | 2.66 | .008 |

| QLS Objects and Activities | 7.56 | 1.79 | 8.39 | 1.77 | 3.44 | .001 |

| QLS Instrumental Role | 11.98 | 5.27 | 17.38 | 4.38 | 4.50 | .001 |

| MCCB Composite | 35.19 | 7.34 | 38.52 | 6.44 | 2.70 | .001 |

| UPSA-B Total Score | 74.05 | 13.33 | 79.64 | 12.90 | 2.87 | .001 |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants MH078775 to Dr. Harvey and MH078737 to Dr. Patterson from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Dr. Harvey has received consulting fees from Abbott Labs, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Johnson and Johnson, Pharma Neuroboost, Roche Parma, Sunovion Pharma, and Takeda Pharma during the past year. Dr. Patterson has served as a consultant for Abbott Labs and Amgen. No other authors have competing interests to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1979;108:441–85. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.108.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC, et al. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:826–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador XF, Gorman JM. Psychopathologic domains and insight in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1998;21:27–42. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, et al. Prediction of Real-World Functional Disability in Chronic Mental Disorders: A Comparison of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1116–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real world functional performance in schizophrenia: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;2006:418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, Halpern B, Patterson T, Harvey PD. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41:1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson G, Lysaker P, Bell M. Quality of life benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2002;28:249–257. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdick KE, Endick CJ, Goldberg JF. Assessing cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder: are self-reports valid? Psychiatry Research. 2005;136:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone DA, Benedict RH, Munschauer FE, 3rd, Fishman I, Weinstock-Guttman B. Interpreting patient/informant discrepancies of reported cognitive symptoms in MS. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2005;11:574–83. doi: 10.1017/S135561770505068X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D, Story AL. Depression, realism, and the overconfidence effect: Are the sadder wiser when predicting future actions and events? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:521–32. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlinger J, Johnson K, Banner M, Dunning D, Kruger J. Why the unskilled are unaware: further explorations of (absent) self-insight among the incompetent. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2008;105:98–121. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fett AK, Viechtbauer W, Dominguez MD, Penn DL, van Os J, Krabbendam L. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review. 2011;35:573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Penn DL. Social cognition: The key factor predicting social outcome in people with schizophrenia? Psychiatry (Edgemont) 2010;7:41–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Raykov T, Twamley EW, Vella L, Heaton RK, Patterson TL. Validating the measurement of real-world functional outcome: Phase I results of the VALERO study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1195–201. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Sabbag S, Prestia D, Durand D, Twamley EW, Patterson Tl. Functional Milestones and Clinician Ratings of Everyday Functioning in People with Schizophrenia: Overlap Between Milestones and Specificity of Ratings. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:1546–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Velligan DI, Bellack AS. Performance-based measures of functional skills: usefulness in clinical treatment studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1138–1148. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT., Jr The Quality of Life Scale: An instrument for rating the schizophrenia deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1984;10:388–396. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR. Positive and negative syndromes in schizophrenia. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RSE, Poe M, Walker TM, Kang JW, Harvey PD. The schizophrenia cognition rating scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:426–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman L, Lieberman J, Dube S, Mohs R, Zhao Y, Kinon B, Carpenter W, Harvey PD, Green MF, Keefe RS, Frank L, Bowman L, Revicki DA. Development and psychometric performance of the schizophrenia objective functioning instrument: An interviewer administered measure of function. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;107:275–85. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifker FR, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. The determinants of everyday outcomes in schizophrenia: Influences of cognitive impairment, clinical symptoms, and functional capacity. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;115:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifker FR, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Validating measures of real-world outcome: the results of the VALERO Expert Survey and RAND Panel. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37:334–343. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, et al. Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:437–441. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Assessing disability in older patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:405–413. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000130133.32276.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, Twamley ET, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Usefulness of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA) for predicting residential Independence in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;42:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Depp CA, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, McGrath JA, Thronquist MA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the UCSD performance-based skills assessment (UPSA-B) for identifying functional milestones in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;132:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT. Cognition and work functioning in schizophrenia. In: Harvey PD, editor. Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia: Characteristics, Assessment, and Treatment. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: In press. [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Thysen J. Insight into neurocognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:1221–30. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Thysen J. A comparison of insight into clinical symptoms versus insight into neuro-cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuchterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch D, Cohen J, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery: Part 1. Test selection, reliability, and validity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz J, Levine S, Garibaldi G, Bugarski-Kirola D, Galani C, Kapur S. Negative symptoms have greater impact on functioning than positive symptoms in schizophrenia: Analysis of CATIE data. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;137:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, et al. Investigators Group. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, Heaton RK, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Assessing everyday functioning in schizophrenia: Not all informants seem equally informative. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;131:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbag S, Twamley E, Vella L, Heaton R, Patterson T, Harvey P. Predictors of the accuracy of self-assessment of everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;137:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LC, Streuening EL. SLOF: A behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Social Work Research and Abstracts. 1983;6:9–21. doi: 10.1093/swra/19.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spikman JM, van der Naalt J. Indices of impaired self-awareness in traumatic brain injury patients with focal frontal lesions and executive deficits: implications for outcome measurement. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1195–202. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Wood RC, Hellemann GS. Symptom domains and neurocognitive functioning can help differentiate social cognitive processes in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr067. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.