Abstract

Data on the compatibility of evidence-based treatment in ethnic minority groups are limited. This study utilized focus group interviews to elicit Mexican American women’s (N = 12) feedback on a cognitive behavior therapy guided self-help program for binge eating disorders. Findings revealed 6 themes to be considered during the cultural adaptation process and highlighted the importance of balancing the fidelity and cultural relevance of evidence-based treatment when disseminating it across diverse racial/ethnic groups.

Keywords: cognitive behavior therapy, guided self-help, eating disorders, Latinas/Latinos, culturally adapted intervention

Research has demonstrated that eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (BED) occur in Mexican American women and pose serious mental and physical health risks (Cachelin, Phinney, Schug, & Striegel-Moore, 2006; Cachelin, Schug, Juarez, & Monreal, 2005; Cachelin, Veisel, Striegel-Moore, & Barzegarnazari, 2000). Bulimia is characterized by recurrent binge eating, inappropriate compensatory behavior, and overvaluation of body shape and weight (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) and is associated with considerable psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial problems. BED is defined by recurrent binge eating in the absence of inappropriate compensatory behaviors that are required for the diagnosis of bulimia. Additional BED criteria include the presence of at least three of five behavioral indicators of loss of control over binge eating (e.g., eating when not hungry, eating in secret), as well as distress over binge eating behavior (APA, 2000). As with bulimia, BED is associated with considerable medical and psychiatric comorbidity (Wonderlich, Gordon, Mitchell, Crosby, & Engel, 2009). Furthermore, obesity, which has been shown to contribute to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and Type II diabetes as leading causes of death in the United States, is a major medical complication in BED (Marcus & Wildes, 2009; Wonderlich et al., 2009).

Recent studies suggest that lifetime prevalence estimates for bulimia and BED among Latinas ranged from 1.9% to 2.0% and from 2.3% to 2.7%, respectively (Alegria et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2010). These numbers are similar to those reported for the general population of U.S. females (Granillo, Jones-Rodriguez, & Carvajal, 2005).Latina women have reported less drive for thinness and consequently may be less likely to compensate for their eating binges than White women are (Marques et al., 2010). Obesity, which often accompanies BED, is recognized as a major health issue for Mexican Americans (Kuczmarski, Flegal, Campbell, & Johnson, 1994).

Despite their chronicity and severity, eating disorders largely go undetected and untreated (Becker, Hadley Arrindell, Perloe, Fay, & Striegel-Moore, 2010; Cachelin, Rebeck, Veisel, & Striegel-Moore, 2001; Cachelin, Striegel-Moore, & Regan, 2006). Although there is growing evidence of eating disorders as a health problem in Mexican and other Hispanic American women, these women are rarely seen in eating disorder clinics and are largely excluded from or underrepresented in treatment trials and research (Garvin & Striegel-Moore, 2001). In one study, Cachelin and Striegel-Moore (2006) found that fewer than 28% of a sample of Mexican American women with clinically significant eating disorders had ever sought treatment, and, of this group, only five women (6.6%) had actually received treatment. Of the few who do seek treatment, most turn to primary care physicians. Barriers reported by this group include feelings of shame, fear of stigmatization, believing that one should be able to help oneself, minimizing the eating problems, financial constraints, language barriers, limited knowledge of and access to health care services, and logistical challenges, such as long waits to see doctors and lack of child care (Cachelin et al., 2001; Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006). Such findings underscore the great need in this population for accessible treatment.

Overview of Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Guided Self-Help

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is widely considered to be the treatment of choice for bulimia and BED (Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007). According to the cognitive behavior model, the core psychopathology of binge eating is a negative overconcern with body shape and weight that leads to dysfunctional dieting and other unhealthy weight-control behaviors. The dysfunctional dieting, in turn, predisposes one to binge eating. CBT consists of cognitive and behavioral procedures designed to enhance motivation for change, replace dysfunctional dieting with a regular and flexible pattern of eating, decrease undue concern with body shape and weight, and prevent relapse. CBT for eating disorders involves three basic stages. In Stage 1, self-monitoring of eating and techniques to help the client establish normalized eating patterns are introduced. Coping mechanisms are also taught to help the client deal with emotional distress. Stage 2 focuses on cognitive restructuring, including identifying and challenging maladaptive cognitions, such as the overvaluation of weight and shape. In Stage 3, relapse prevention techniques are taught to promote the maintenance of change posttreatment (Grilo, 2006). Because there is no research to date focused on non-European cultural groups, the effects of acculturation and language of intervention on treatment acceptability are not known and are explored in the current study.

CBT requires specialized training and expertise, making it less readily available. Hence, implementation science researchers have begun to examine the effectiveness of CBT-based guided self-help (GSH) as a more easily disseminated intervention or first step in the treatment of binge-eating-related problems (DeBar et al., 2011; Lynch et al., 2010; Striegel-Moore et al., 2010). CBT-GSH is a low-intensity intervention in which clients use a self-help manual with only limited support and instruction from either a specialist or nonspecialist in clinical or nonclinical settings. A typical CBT-GSH program consists of following a self-help manual with programmatic steps based in CBT and attending regular guidance/support sessions with a “coach” or “supporter.” A few such programs have been developed with similar components (e.g., Masheb & Grilo, 2008; Traviss, Heywood-Everett, & Hill, 2011). The most commonly evaluated CBT-GSH program is the one developed by Fairburn (1995), Overcoming Binge Eating. The program consists of following six steps of a self-help manual accompanied by eight guidance/support sessions (25 minutes each), with more sessions clustered early in the treatment period: four weekly sessions followed by four biweekly sessions. The program is designed to be delivered by personnel with no background in the use of CBT or expertise in the treatment of bulimia or BED. The book is available in English and Spanish and has two sections. The first section is educational and summarizes current knowledge about binge eating, BED, and bulimia and provides the rationale for the self-help program. The second section of the book presents the program itself, which consists of six steps on how to change eating habits or other associated problems. The steps are additive and are meant to be followed in sequence (Fairburn, 1995):

Getting started: self-monitoring and weekly weighing

Establishing a pattern of regular eating and stopping vomiting and laxative misuse

Substituting alternative activities for binge eating

Practicing problem solving and reviewing progress

Tackling dieting and other forms of avoidance of eating

Preventing relapse and dealing with other problems

The program’s primary focus is to develop a regular pattern of moderate eating using self-monitoring, self-control strategies, and problem solving. Additionally, relapse prevention is emphasized to promote maintenance of behavioral change.

The principal role of the guide or supporter is to explain the rationale for using the self-help book, generate a reasonable expectancy for a successful outcome, and motivate the participant to use the book as a guide for proceeding through the program steps. The support sessions are program-led and follow the manual developed by Fairburn (1998). The manual specifies the length and tone of the sessions, how the supporters should prepare in advance for the sessions, and the elements that should be followed in each session. The role of the supporter is not to provide education or skills training to the participant (which would undermine the self-help nature of the program). Previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of nonspecialists as supporters for such CBT-GSH programs (Bailer et al., 2004; Dunn, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2006).

CBT-GSH is most appropriate for individuals whose primary symptom is binge eating, who have less severe eating pathology, and who have lower levels of psychiatric comorbidity. As a minimal intervention, it is not indicated for individuals with anorexia, who need medical and clinical attention to address low weight; those who are morbidly obese and need targeted behavioral weight-loss strategies; or those with more serious clinical concerns (e.g., suicidality, severe depression). In a specialty clinic setting, CBT-GSH can be used as the first step in a stepped care approach and can even prime the response to further treatment (Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, 2010). In nonspecialty settings, it can be delivered by nonspecialists (e.g., nurses, primary care physicians) to individuals who otherwise would not be able to access care. The acceptability and effectiveness of the program in community settings have not been established and are the focus of the research described here.

Research conducted primarily with White women has demonstrated CBT-GSH to be effective in reducing binge eating and vomiting, decreasing shape and weight concerns and related eating-disorder pathology, reducing depression, and improving self-esteem (Sysko & Walsh, 2008; Wilson et al., 2007). Reported remission rates from binge eating range from 24% to 74%, and improvement is typically maintained at 12- and 18-month follow-ups (Bailer et al., 2004; Grilo, 2006). CBT-GSH has also been shown to be as effective as specialty interpersonal therapy and significantly superior to behavioral weight loss in treating BED (Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Wilson et al., 2010). Despite its promise, experts agree that considerably more community-based research is needed before CBT-GSH can be disseminated widely (Grilo, 2006; Sysko & Walsh, 2008). Most notable is the lack of ethnic representation in this body of research. No studies to date have systematically examined the efficacy of CBT-GSH with ethnic minority groups, and fewer than 5% of participant samples in published studies of CBT-GSH have been non-Caucasian (Miller, 2004). This gap in research is surprising given that these groups are those most in need of accessible treatment.

Given the effectiveness of CBT-GSH for treating binge-eating-related disorders and the empowering components of self-help, we hypothesized that this treatment modality would appeal to Mexican American women with bulimia and BED. Mexican American women who suffer from binge-eating-related disorders often report wanting help for their eating problems, yet they rarely seek professional treatment because of personal and institutional barriers (Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006). By its nature, self-help intervention reduces or eliminates most of these barriers to treatment seeking. Self-help can be brief, inexpensive, nonstigmatizing, empowering, and broadly accessible (Apfel, 1996; Garvin, Striegel-Moore, Kaplan, & Wonderlich, 2001), making it feasible to administer to a population that tends to underutilize professional psychological services. The CBT approach promotes client–practitioner collaboration and values understanding of individuals’ subjective experiences in context, so it can be tailored to individuals from diverse backgrounds (Shea & Leong, 2012).

Cultural Adaptation for Treatment of Eating Disorders

Research has indicated that incorporating cultural components into existing treatment can be beneficial for ethnic minority and underserved populations (Shea & Leong, 2012; Vega et al., 2007). Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia, and Butler (2000) suggested that cultural sensitivity and adaptation can occur on two levels. Surface structure adaptation includes matching intervention programs and materials to the superficial characteristics of a target population, such as the language and contents of the program. Deep structure adaptation involves understanding the role of contextual factors—such as culture, socioeconomic status, and political and historical environments—in the conception and manifestation of health behaviors across racial/ethnic groups.

The need for cultural adaptation for the treatment of eating disorders is supported by anthropological literature demonstrating that eating behaviors and practices are culturally and socially determined (Logue, 1991) and by empirical research demonstrating ethnic differences in the presentation of eating disorder symptoms (Brown, Cachelin, & Dohm, 2009). For example, Black and Hispanic women have reported less drive for thinness than have White women, presumably because of cultural differences in the valuation of thinness. Similarly, perceptions of both food amount and body size may be influenced by ethnicity (Cachelin, 2001; Dohm, Cachelin, & Striegel-Moore, 2005). Specifically, Latino culture tends to place a high degree of importance on food and eating and, at the same time, on women’s physical appearance. Moreover, Latina women are typically taught that taking care of their bodies and their health should be secondary to taking care of others (Lozano-Vranich & Petit, 2003). These results highlight the importance of considering the cultural beliefs and values of Latinas, as well as their changing social contexts (e.g., social support network), life experiences (e.g., immigration), and acculturative stress, when attempting to implement the CBT-GSH program.

The purpose of this study was to explore the feasibility and cultural relevance of the CBT-GSH program for Mexican American women diagnosed with bulimia or BED before dissemination in this population. A secondary goal was to discuss which components, as determined by Mexican American women themselves after they had read the manual, should be incorporated into the culturally adapted CBT-GSH program. Qualitative methodology is recommended for cultural adaptation because of its ability to discover complex and diverse sociocultural realities from participants’ subjective lenses (Bernal & Scharró-del-Río, 2001). Focus groups are an effective means to convene members of the target population and explore their feelings, thoughts, and experiences regarding a specific problem (Resnicow et al., 2000). We asked two research questions: (a) From the view of Mexican American women with binge eating problems, how feasible and relevant would it be to culturally adapt the CBT-GSH for treating bulimia and BED? (b) Which cultural components should be considered and incorporated into the culturally adapted GSH treatment?

Method

Participants

Twelve Mexican American women participated in three focus groups: two English-speaking (n = 7) and one Spanish-speaking (n = 5). The mean age was 32.8 years (SD = 9.2), with an age range of 24 to 52. All English-speaking participants were second-generation immigrants; the majority were single and did not have children. All but one of the Spanish-speaking participants were first-generation immigrants, and they were all married with children. Ten of the 12 participants were employed. These women were recruited because they had participated in a previous study that examined treatment-seeking barriers among Latinas (Cachelin, Striegel-Moore, & Regan, 2006) and had met diagnostic criteria for bulimia or BED (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; 4th ed., text rev.; APA, 2000). During the interview, five women reported having previously sought professional treatment.

Procedure

Participants were invited to participate in a 2-hour focus group conducted in an urban public university on the West Coast of the United States. They were informed that they would receive monetary compensation for their participation. Twelve women responded and were assigned to one of three focus groups based on their availability and preferred spoken language.

Participants received a packet containing a demographic form, a copy of the CBT-GSH manual Overcoming Binge Eating (Fairburn, 1995), a list of focus group questions about the CBT-GSH manual, and a list of local referral resources for eating disorder treatment. Participants were instructed to read Steps 1 to 6 and consider the questions that assess the feasibility of the GSH manual in the Mexican American community prior to attending the focus group session. Following the Stage Model of Behavioral Therapies (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2006), participants were given 30 days to review and reflect on the manual, but were not asked to actually engage in the program at this stage. With the exception of one participant, none of the women were familiar with the treatment approach prior to receiving the manual.

Procedures for conducting the focus groups followed published guidelines and previous research (Yeh, Kim, Pituc, & Atkins, 2008). A trained, experienced bilingual (English and Spanish) research assistant facilitated all focus groups. During each group, a note taker recorded detailed notes about the content of the discussion, nonverbal behaviors, and any other significant events (e.g., someone crying). The focus group session began with an introduction of the study purpose and the interview process. Group discussions were first elicited by asking participants two open-ended questions: “What do you think of the CBT-GSH program and manual?” and “What themes or cultural components do you think should be considered and incorporated in the CBT-GSH program?” Open-ended questions helped minimize researchers’ bias and grant a privilege to participants’ responses. Following open-ended questions, probing questions focused on participants’ feedback on each of the six steps of the CBT-GSH manual. Sample questions included, “What do you like/dislike about it (each specific step) and why?” and “What is most helpful/least helpful about it (each specific step) and why?” Additional probes explored issues of program feasibility and engagement in the Mexican American community, which also allowed participants to elaborate on the cultural components they considered important to incorporate into the CBT-GSH program.

We followed a rigorous procedure of transcription and translation. Audiotapes were transcribed and checked against the original tapes by one of the raters. Spanish transcripts were transcribed in Spanish, then translated into English, and translated back into Spanish by a separate rater (Brislin, 1980). Any discrepancies about the translation were discussed among bilingual raters until a consensus was reached.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness of Data

Grounded theory was used because it encourages insight into participants’ experiences and facilitates the discovery of meanings of the data through systematic data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Two raters read and coded each transcript. Data analysis began with open coding, which involves coding the smallest, most discrete units of meaning and labeling them as concepts. The second level of coding is axial coding, which consists of creating a higher level of conceptualization of data—categories. Relationships among categories are then analyzed in terms of their properties (i.e., characteristics of a category) and dimensions (i.e., location of a category along a continuum), organizing them into more encompassing key categories or core themes (Fassinger, 2005). During the final step, selective coding, the raters read the transcripts again, outlined the interrelationships of the core themes, and looked for convergent and divergent ideas across all of the groups to create a coherent story line (i.e., emerging theory) that articulated the most important aspects of the data (Fassinger, 2005).

Trustworthiness in qualitative research refers to the authenticity and consistency of the research findings grounded in the data (Yeh et al., 2008). Several steps were taken to minimize bias in data collection and analytic and interpretation procedures. First, focus group data were analyzed by raters who had not served as the focus group facilitator or note takers. Second, the two raters compared their coding of the categories and themes and discussed any discrepancies until a consensus was reached. A preliminary set of core themes was shared with the facilitator of the focus group to provide a rigorous check of the data analysis. Third, researcher reflexibility was emphasized. Raters reflected on and discussed in research meetings their potential biases, assumptions, and reactions during data analysis. Finally, two participants who had previously agreed to review the findings read all of the themes and subcategories to provide a stability check of the data. The additional comments were incorporated into the final version.

Results

Six main themes emerged from the data that compose a theoretical schema describing Mexican American women’s challenges and barriers in treatment seeking, as well as their strengths and resilience. These themes also highlight the cultural components that participants would like the CBT-GSH program to address to enhance the program’s cultural relevance.

Cultural Expectations and Acculturation Differences

Participants experienced tensions and conflicts with others in their family, their community, and within themselves regarding their eating problems, as a result of different cultural beliefs, values, and acculturation levels. These differences were reflected in the understanding of eating disorders, importance placed on body image, and expectations toward the responsibilities of Latinas.

Participants reported that their family members, particularly those from older generations, tended to be less acculturated and less knowledgeable about eating disorders. Thus, family members were sometimes unable to identify with participants’ experience. One participant said,

None of my aunts, any of them, and they’re all Mexicans and they didn’t even know what that was. Only of course my sisters and my brothers…. They didn’t know until they like went, Google it, and said, “OK so this is what she has.”

Another participant shared that her family tended to downplay her problem:

And back then, you know, they didn’t have like TV, all the pressure from media outlets or peer pressure to look a certain way. It was more like, “You have to work hard. Forget your looks, forget how you feel.”

Younger and more acculturated participants tended to experience pressure to live up to the mainstream norms of body image. One participant expressed:

I feel like there is that correlation as a Latina. Because I had to face the fact that … like, I’m never gonna be a size 4, I’m never gonna be tall and skinny … I’m not gonna look like Kate Moss…. And that’s why you see girls starving themselves.

As Mexican American women, participants were often expected to adhere to traditional cultural values and roles, such as attending to others’ needs and prioritizing group goals above personal goals. At the same time, they tried to embrace new cultural norms and values that encourage them to pursue personal interests and accomplishments. Participants indicated that the CBT-GSH manual did not address how to negotiate these competing priorities and needs:

So I think they [the book] kind of have to address a little bit about that because you know, everybody, like I said, it comes down to the scheduling, we all eat at different times and it always falls on [family schedules].

Role of Family

Participants identified two areas in which family can potentially influence their treatment engagement: family’s attitudes toward their weight and shape concerns, and family’s involvement in the treatment process. Participants reported that their family members often voiced strong opinions regarding their weight and shape concerns. Family’s attitudes could range from critical and overbearing to well-intentioned but misguided. One participant said,

They can be a big influence on you and when they say things, it is hurtful. You do take it internally and you can go back to when you were a small child and overweight…. I can still hear comments that my dad makes today, if I’m going to eat something.

Another participant shared that although her husband wanted to help her, he was not well-informed about the disorder:

He wants to help me lose weight, but he doesn’t understand what triggers my binges. He’s very strict on me, maybe that’s another trigger … it’s hard for me because sometimes I feel like I have to hide [my eating] from him … but I cannot always do that.

Participants were divided in their views toward family’s involvement in the CBT-GSH process. Participants in the Spanish-speaking group tended to support involving family members in the treatment process, indicating that family is an integral part of their lives. One participant, who had tried to include family members in her previous treatment, affirmed that “I told my mother and my husband, ‘I’m doing this because I want to be healthy. You know, I want to see my kids grow up.’ They were very understanding, believe it or not.”

The English-speaking group participants, however, expressed skepticism about including family members. They also viewed treatment seeking as a personal matter. A participant elaborated on this issue:

I would never tell anybody, my family about my food issues. Why? Because they would laugh at me … that’s just our culture … in a Mexican household setting, you wouldn’t share your food log with anybody because it’s private, that’s personal.

Meaning of Food

Participants expressed that food carries multiple social and emotional meanings in Mexican culture, which could pose challenges to their ability to manage their eating problems and to the treatment success. As one participant said, “You always have that saying, like the parents, ‘Comida es sagrada,’ food is very sacred, you don’t waste it.” Refusing food or not taking a second helping may be perceived as being disrespectful. One participant shared her dilemma:

It’s more than just food. It’s like food is love with your family. Like the more my grandma loves me, the more she feeds me…. You feel really guilty saying no because that’s how she shows that she loves you. My grandma is not going to go and hug me, she’s going to go and feed me. So, it’s like you’re saying no to more than just food.

Participants also explained that food symbolizes abundance and hospitality in their community. Therefore, social gatherings and activities tend to revolve around food, and serving portions are large. The culturally prescribed eating patterns may increase Mexican American women’s vulnerabilities to overeating. As one participant said, “We don’t understand that it is binge eating; we just understand that it’s a big meal and it’s normal.” Participants felt that the manual should address how to maneuver social gatherings that frequently involve food.

Feelings Toward Eating Disorders and Recovery

Participants identified that their own emotions can be a barrier to treatment success in the CBT-GSH program. They often experienced guilt and shame about their disordered eating. One participant said, “You like guilt yourself, ‘Oh my God, I ate two of this and I should have just had one.’ So I’m not gonna eat anything until breakfast the next day.”

Participants’ feelings toward their eating disorders and recovery process were intertwined. One participant shared the following:

I’d get anxious because … it was like, my problem … for the first time I’m really facing it, so I had to put it [the GSH manual] down, and then I would have to come back and … it was just very emotional for me reading this.

Despite their difficult feelings, participants talked about hope, perseverance, and determination to prevail in the CBT-GSH program. As one participant said, “I think that where there’s a will, there’s a way. If one wants to do things, one has to do them.”

Help-Seeking Attitudes and Strategies

Mexican American women with eating disorders experienced loneliness and alienation because of the shame and secrecy of their problems. One participant stated that she used to struggle with her eating problems on her own: “You know, it was years into my bulimia before I thought, ‘OK, I need to talk to somebody,’ because I have no one to talk to and I don’t know what I’m doing anymore.”

Most participants preferred seeking help from informal sources, such as friends, family, church, and community resources (e.g., self-help groups). One participant said, “You have to have support, be it your friend, your husband.” At the same time, participants expressed concerns and reluctance to seek professional help because of the stigma attached to receiving psychological help in their community. One participant, who had sought professional help, highlighted the resistance to seeking professional help among her friends:

I’ve gone to therapy, so I don’t think anything of it. But sometimes when I talk to friends and hear them talk about similar issues that they’re having, I’m like, “Hey, why don’t you talk to someone?” My friend said, “No, it’s not for me. I don’t need that stuff.” But I think it is part of [their shame] … it’s stigmatized.

Evaluation of the CBT-GSH Manual

Participants responded favorably to the CBT-GSH manual. One participant shared the following:

I felt that the book was really thorough. I’ve always had issues with food. I had the fortune of going to Weight Watchers when I was younger. It [information received at Weight Watchers] kind of went hand-in-hand with a lot of the things that they [the manual author] promote here, only that here they really went a step further and really analyzed why people have the eating patterns that they do.

However, participants indicated that the presentation and the contents of the book need to be adapted to make it more culturally relevant to the Mexican American community. Some of its contents may not be applicable to Mexican Americans. For instance, the book did not include examples of Mexican food. One participant said, “Whether we’ve been acculturated or not, we traditionally still eat some of these foods.” Another participant stated that the manual did not include sufficient alternative activities (to binge eating) that are suitable for women living in a low-income neighborhood:

I remember I wasn’t even able to get in control of my weight until I was in college, until I bought my own car, because that gave me the freedom to say, “I’m gonna go to the gym,” or “I’m gonna go and get away.” Because until then, I was stuck there with my parents … there’s nowhere for me to go. I can’t go walk around the block; I’m gonna get shot.

Participants suggested that the presentation of the CBT-GSH manual should be contextualized to reflect Mexican American women’s life experiences, preferences, and needs. A few participants noted that the manual lacks culturally relevant role models and references. Others pointed out that the book has too much jargon: “The themes, to me … this book was perfect. But I would have liked, there aren’t that many words, maybe not everyone is familiar with certain words in the book.”

Participants described that many Latinas—especially younger ones—still live with their parents and family. Thus, the CBT-GSH manual should address interpersonal stressors that are common in Mexican families. One participant said, “I think if you’re looking for improvement, then you would add Mexican scenarios.”

Discussion

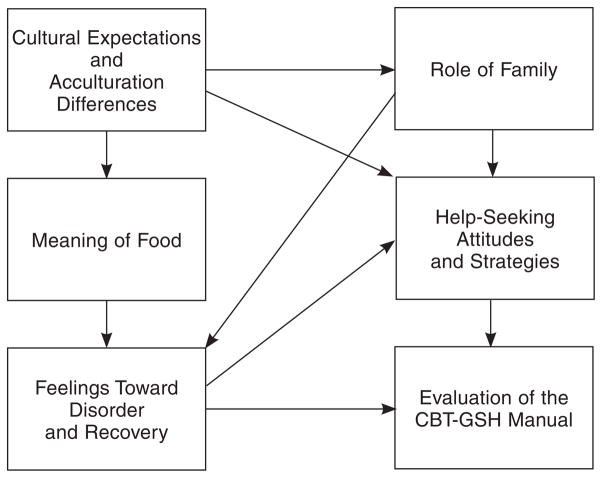

Consistent with previous studies, our findings indicate that Mexican American women with bulimia or BED do want help for their eating problems but experience a multitude of personal and contextual barriers (Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006; Cachelin, Striegel-Moore, & Regan, 2006). A unique aspect of the grounded theory method is that it goes beyond description and a list of themes. The approach generates a story—a thematic schema that organizes and illuminates the process, interaction, and action shared and shaped by the participants (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In the next three sections, we discuss how the six themes discussed in this study dynamically relate to one another (see Figure 1) and how they inform a number of changes to the CBT-GSH program for Mexican American women.

FIGURE 1. Interrelationships of Themes.

Note. CBT-GSH = cognitive behavior therapy guided self-help.

Culture, Food, and Family

Culture not only defines Mexican American women’s roles and responsibilities as Latinas but also shapes traditions and daily practices, such as meal patterns and social relationships. Mexican Americans tend to identify with collectivistic values (Rinderle & Montoya, 2008), which emphasize interdependence, respeto (respect for elders and authority), simpatia (harmony in relationships), and prioritizing group goals over personal goals. Latinas, in particular, have been socialized to value taking care of others more than taking care of their own needs (Lozano-Vranich & Petit, 2003).

Mexican American women may also experience acculturative stress as they come into contact with the mainstream American culture. Scholars in femininity research suggest that dominant cultural (i.e., European American) feminine norms, such as thinness, are pervasive in U.S. society and are likely to affect all women, including those from racial/ ethnic minority groups (Mahalik et al., 2005). As Latinas become more acculturated to American culture, they may feel the pressure to live up to the mainstream standards of body image and the thin ideal.

Participants in our study reported constant challenges of navigating different cultural expectations. For instance, they were concerned about being disrespectful to their family members (especially the older adults) and disrupting social harmony when they try to monitor their food intake, because food is central to social gatherings in Mexican communities and carries symbolic meanings in interpersonal exchanges (Lindberg & Stevens, 2011). Their struggles in balancing familial responsibilities with their personal interests illustrate the conflicts between traditional and mainstream values, as well as the bicultural stress faced by many Latinas.

Culture, Family, Help-Seeking Strategies, and CBT-GSH

Consistent with previous findings on help-seeking barriers among Mexican American women with eating disorders (Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006), most participants felt ashamed about their eating disorders and preferred to seek support from informal sources because of stigma associated with receiving professional help for these issues. Past studies showed that Mexican Americans adhere to familism, a cultural value that emphasizes obligation and connectedness to one’s family members (Cuellar, Arnold, & González, 1995; Rinderle & Montoya, 2008). Our findings, however, revealed a slightly different portrait of Mexican American family dynamics. Some participants reported a strong identification with their family. Others described their family as overbearing and intrusive; thus, they wished to keep their treatment decision private. The extent to which Mexican American women would involve their family members in their treatment might be influenced by the specific family constellation and dynamics. It is possible that differential acculturation levels within the family may have contributed to the chasm of understanding and a sense of disconnection between some Mexican American women and their family. These findings underscore the importance of acknowledging widely varying within-group ethnic, acculturation, and cultural differences and the need to avoid perpetuating group stereotypes (e.g., “all Latinos/ Latinas are family-oriented,”) in research and treatment.

Overall, participants responded favorably to the CBT-GSH program and viewed it as a viable alternative to seeking professional help. The CBT-GSH program offers systemic (step-by-step) treatment that can be completed in an informal and less stigmatizing setting (e.g., home). Furthermore, this modality may ease some of the tensions between the participants and their family, because it affords them the privacy, convenience, and flexibility to complete the program at their own pace while fulfilling other responsibilities. Specifically, participants would like to have included in the manual more culturally specific examples, such as interpersonal scenarios, role models, and Mexican food.

Family, Food, Internalized Feelings, and CBT-GSH

There was a sense of despair surrounding participants’ narratives of their eating disorders. Feelings of shame and guilt are common among individuals who suffer from eating disorders (Goss & Allan, 2009), which often lead to the secrecy about their disorders and a profound sense of isolation (Pritchard & Yalch, 2009). Participants’ negative affect and maladaptive coping (including overeating) may be exacerbated by their families’ critical comments about their disordered eating and body image. The prominence of food in the Mexican American community and culturally prescribed meal patterns may predispose these women to cognitions and feelings such as loss of control, anxiety toward social situations, and a perpetual sense of helplessness and failure associated with their overeating.

Participants candidly shared their worries about utilizing the CBT-GSH program, while acknowledging the importance of overcoming their fear and coming to terms with their eating disorders. The resilience of Mexican American women was evident across all focus groups. Contrary to the commonly held Latino belief of fatalism, which posits that one’s destiny is beyond one’s control (Cuellar et al., 1995), participants stated that their success in the CBT-GSH program would be contingent upon their willingness to remain engaged and persist in the treatment process despite constant challenges in their daily lives.

Summary of Adaptations Derived From Focus Groups

Participants’ concerns revolved primarily around maneuvering social situations that involve food, balancing competing priorities and cultural expectations, and managing family interactions. All of these factors may affect their internalized negative self-beliefs, help-seeking behaviors, and treatment motivation and success.

In light of participants’ feedback, we have included an addendum of a role-playing exercise and a Mexican food guide and incorporated multicultural competence training of supporters. We did not modify the content or steps of the manual. The changes are summarized as follows. First, we have elicited input from community members (e.g., research assistants, faculty, community agency partners) of Mexican American descent and developed case vignettes that describe common interpersonal interactions within Mexican family households and social circles. These vignettes are to be incorporated as part of the culturally adapted CBT-GSH intervention and role-played between the participants and their supporters in an orientation session. The role-play exercise serves as a safe haven for participants to discuss some of the difficult issues (e.g., meaning of food, varying cultural expectations regarding body image) and explore ways to address interpersonal dilemmas that may arise during the treatment process. Second, we have crafted a Mexican American food guide with culturally relevant food examples and specific suggestions to help participants gauge their food choices and portion control.

As mentioned earlier, Resnicow et al. (2000) emphasized the need to attend to deep-structure adaptations, such as examining the impact of contextual factors on the treatment process. Thus, our third consideration pertained to promoting supporters’ multicultural competence in service delivery. Through training and clinical supervision, supporters may develop a contextualized understanding of their participants’ worldviews and life experiences, become aware of their own biases and preconceptions about Mexican American women and Latinas in general, and utilize techniques (e.g., cultural metaphors) that are responsive to their participants’ sociocultural realties (Sue, 1998).

The culturally adapted CBT-GSH intervention has been piloted with Mexican American women with bulimia or BED. The outcomes of the pilot study and participants’ responses toward the culturally adapted program will be discussed in a separate article.

Study Limitations

Several limitations to the present study need to be considered. We recruited a convenience sample of Mexican American women from a previous study who had met full clinical criteria for bulimia and BED; hence, caution should be used when generalizing the present findings to Mexican Americans living in other regions of the United States or the broader Latino/ Latina population. The research is also limited in its relatively small sample size (N = 12), which reflects the challenge in recruiting Mexican American women with bulimia or BED from the community. Data from the focus groups provide only a snapshot of participants’ experiences based on the current group interaction; they do not tell us how women’s experiences of their eating disorders or their evaluations of the CBT-GSH change over time. In addition, the participants’ feedback on the CBT-GSH program was based on their reading of the GSH manual and not actual exposure to the intervention. Finally, it is possible that some participants did not feel comfortable sharing their personal experiences in the focus groups because of shame or stigma. Thus, our findings may not fully capture their barriers and challenges in coping with a debilitating disorder.

Directions for Future Research

Future research on cultural adaptation should include more purposive sampling. Involving Latinas from other regions and countries would allow for within-(ethnic) group comparisons. A combination of interviews, focus groups, and ethnography data can be used to increase multiple perspectives, encourage open sharing of experiences among participants, and reduce potential feelings of embarrassment associated with discussing issues in a group (Yeh et al., 2008). In addition, researchers can conduct interviews or focus groups with participants who have undergone the culturally adapted CBT-GSH program to compare their feedback with that of participants who have only read the manual. The findings may enumerate new concepts that will be useful for program refinements.

The current phase of the CBT-GSH feasibility study with Mexican American women relied on qualitative methods and participants’ direct experiences. The qualitative method has been recommended to systemically generate information for developing and culturally adapting evidence-based interventions for racial/ethnic minority groups (Interian, Martinez, Rios, & Krejci, 2010). Although our sample size was rather small, the findings derived from the focus groups were beneficial for understanding the unique perspectives of an underserved minority group and to provide a theoretical framework for further study. The next step in our research is to combine qualitative methods with quantitative ones to examine the efficacy of this culturally adapted intervention via randomized controlled trials.

Implications for Practice

Various factors, as mentioned previously, influence Mexican American women’s motivation and ability to engage in treatment as well as their resilience in the recovery process. Nevertheless, the systemic yet flexible nature of the CBT-GSH intervention may reduce these women’s perceived stigma and barriers to seeking psychological help, thus providing a promising treatment option. Our themes from the focus groups inform counseling practices for Mexican American women with BED, in particular, and possibly for other Latina immigrants who share common experiences. Specifically, immigration and acculturation experiences can lead to changes in family dynamics, cultural expectations (e.g., different meaning of food and body image), levels of social connectedness, and perceived support from one’s family and community. Thus, therapists and counselors can invite their clients to explore how these interpersonal and acculturative factors affect their coping, help-seeking strategies, and internalized feelings and self-efficacy toward their disorder and recovery. For example, we included interpersonal vignettes and role-play exercises as part of the cultural adaptation of the CBT-GSH program. It is critical for counselors not to assume that most Latinas are collectivist and enjoy a lot of support from their community. For some clients, involving family members in the recovery process could render them vulnerable to negative affect and relapses. Hence, counseling professionals should be tentative in applying cultural knowledge and remain observant of potential within-group differences to avoid imposing and reinforcing stereotypes about racial/ethnic minority groups (Sue, 1998).

Moreover, socioeconomic factors such as access to resources, financial pressures, and multiple responsibilities can vastly influence Mexican American women’s motivation and ability to engage in treatment. Counselors must understand their clients’ symptom expression and treatment behavior (e.g., attendance) in context, identify specific barriers that challenge their clients’ adherence and engagement, and embrace a collaborative stance to explore how culturally sensitive and applicable the interventions are to their clients. For example, the CBT-GSH manual offers a specific step in problem solving. Counselors or GSH supporters can guide their clients to utilize the problem-solving skills for working through stress and conflicts related to eating disorders and other life domains. Counselors may also explore the utility of technology, such as mobile phone applications, in helping their clients make plans, monitor treatment progress (e.g., regular eating, bingeing urges), and organize their priorities.

In terms of education and training, counseling professionals should stay abreast of literature and empirical evidence that support the effectiveness of evidence-based treatment, including various forms of cognitive behavior interventions. Counseling programs and educators can provide information to trainees and students about the CBT-GSH program and cultural adaptation and discuss how to integrate these approaches into trainees’ practice.

Finally, counseling professionals can work as advocates and take a proactive stance in educating the professional and lay communities about the prevalence and severity of bulimia and BED among ethnic minority women, as well as the availability and benefits of various treatment options, including the CBT-GSH program. Counselors can also collaborate and facilitate referrals with medical professionals, mental health agencies, and schools to ensure that culturally sensitive and evidence-based interventions are accessible to underserved communities.

Conclusion

One of the key findings from this study is that Mexican American women expressed a positive attitude toward the CBT-GSH program and a desire to engage in it. They found the manual to be well written, comprehensive, and helpful. The cultural adaptation changes that they suggested, albeit important, were relatively minor. Our findings support an integrated treatment framework and highlight the importance of balancing cultural relevance with fidelity to the core components of an evidence-based intervention. Despite the specific adaptations and changes, the intervention remains grounded in CBT principles. The GSH nature of this CBT intervention and the lower implementation cost of the program especially suit the needs of hard-to-reach populations, who would not otherwise seek professional psychological services because of multiple barriers. If successfully implemented, the CBT-GSH may contribute to closing the gaps in ethnic minority health disparities and serve as an entry point for ethnic minorities to seek professional psychological services. Furthermore, this study can serve as a basis for developing self-help treatments for other mental health disorders that can be made accessible to ethnic minority populations, who continue to be under-represented in clinical research and intervention

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (1SC1MH087975). The authors also acknowledge the support and assistance from the Women’s Health Project Lab at California State University, Los Angeles.

Contributor Information

Munyi Shea, Department of Psychology, California State University, Los Angeles.

Fary Cachelin, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

Luz Uribe, Department of Psychology, California State University, Los Angeles.

Ruth H. Striegel, Department of Psychology, Wesleyan University

Douglas Thompson, Thompson Research Consulting LLC, Chicago, Illinois.

G. Terence Wilson, Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology, Rutgers the State University of New Jersey.

References

- Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng X, Striegel-Moore R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S15–S21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Apfel R. “With a little help from my friends I get by”: Self-help books and psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 1996;59:309–321. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1996.11024771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer U, de Zwaan M, Leisch F, Strnad A, Lennkh-Wolfsberg C, El-Giamal N, Kasper S. Guided self-help vs. cognitive-behavioral group therapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:522–537. doi: 10.1002/eat.20003 ‘. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AE, Hadley Arrindell A, Perloe A, Fay K, Striegel-Moore RH. A qualitative study of perceived social barriers to care for eating disorders: Perspectives from ethnically diverse health care consumers. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:633–647. doi: 10.1002/eat.20755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Scharró-del-Río MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:328–342. doi: 10.1037//1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of cross cultural psychology. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1980. pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Cachelin FM, Dohm FA. Eating disorders in ethnic minority women: A review of the emerging literature. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2009;5:182–193. doi: 10.2174/157340009788971119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM. Ethnic differences in body size preferences: Myth or reality? Nutrition. 2001;17:353–356. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Phinney J, Schug RA, Striegel-Moore RH. Acculturation and eating disorders in a Mexican American community sample. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:340–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Rebeck R, Veisel C, Striegel-Moore RH. Barriers to treatment for eating disorders among ethnically diverse women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:269–278. doi: 10.1002/eat.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Schug RA, Juarez LL, Monreal TK. Sexual abuse and eating disorders in a community sample of Mexican American women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:533–546. doi: 10.1177/0739986305279022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH. Help seeking and barriers to treatment in a community sample of Mexican American and European American women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:1544–1561. doi: 10.1002/eat.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH, Regan PC. Factors associated with treatment seeking in a community sample of European American and Mexican American women with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14:422–429. doi: 10.1002/erv.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Veisel C, Striegel-Moore RH, Barzegarnazari E. Disordered eating, acculturation and treatment seeking in a community sample of Hispanic, Asian, Black, and White women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24:244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00206.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, González G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:339–356. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199510)23:4<339:AID-JCOP2290230406>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeBar LL, Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, Perrin N, Yarborough BJ, Dickerson J, Kraemer HC. Guided self-help treatment for recurrent binge eating: Replication and extension. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:367–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.4.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohm FA, Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH. Factors that influence food amount ratings by White, Hispanic, and Asian samples. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1061–1069. doi: 10.1038/ oby.2005.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Motivational enhancement therapy and self-help for binge eaters. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:44–52. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Guided self-help for bulimia nervosa: Therapist’s manual for use in conjunction with Overcoming Binge Eating (Fairburn, 1995) Oxford, England: University of Oxford, Department of Psychiatry; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger RE. Paradigms, praxis, problems, and promise: Grounded theory in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:156–166. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin V, Striegel-Moore RH. Health services research for eating disorders in the United States: A status report and a call to action. In: Striegel-Moore RH, Smolak L, editors. Eating disorders: Innovative directions in research and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 135–152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin V, Striegel-Moore RH, Kaplan A, Wonderlich S. The potential of professionally developed self-help interventions for the treatment of eating disorders. In: Striegel-Moore RH, Smolak L, editors. Eating disorders: Innovative directions in research and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Goss K, Allan S. Shame, pride, and eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2009;16:303–316. doi: 10.1002/cpp.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granillo T, Jones-Rodriguez G, Carvajal SC. Prevalence of eating disorders in Latina adolescents: Associations with substance use and other correlates. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM. Eating and weight disorders. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Martinez I, Rios LI, Krejci J. Adaptation of a motivational interviewing intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:215–225. doi: 10.1037/ a0016072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Campbell SM, Johnson CL. Increasing prevalence of overweight among U.S. adults. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:205–211. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg NM, Stevens VJ. Immigration and weight gain: Mexican-American women’s perspectives. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Mental Health. 2011;13:155–160. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue AW. The psychology of eating and drinking. New York, NY: Freeman; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Vranich B, Petit J. The seven beliefs: A step-by-step guide to help Latinas recognize and overcome depression. New York, NY: Rayo/Harper Collins; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch FL, Striegel-Moore RH, Dickerson JF, Perrin N, DeBar L, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. Cost-effectiveness of guided self-help treatment for recurrent binge eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:322–333. doi: 10.1037/a0018982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Morray EB, Coonerty-Femiano A, Ludlow LH, Slattery SM, Smiler A. Development of the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory. Sex Roles. 2005;52:417–435. doi: 10.1007/ s11199-005-3709-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus MD, Wildes JE. Obesity: Is it a mental disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:739–753. doi: 10.1002/eat.20725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen C-N, Fang A, Chosak A, Diniz JB. Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: Implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;44:1–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Examination of predictors and moderators for self-help treatments of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:900–904. doi: 10.1037/a0012917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ. A review of workbooks and related literature on eating disorders. In: L’Abate L, editor. Using workbooks in mental health: Resources in prevention, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation for clinicians and researchers. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 2004. pp. 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard ME, Yalch KL. Relationships among loneliness, interpersonal dependency, and disordered eating in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j. paid.2008.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, Ahluwalia JS, Butler J. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:271–290. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(200005)28:3<271::AID-JCOP4>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinderle S, Montoya D. Hispanic/Latino identity labels: An examination of cultural values and personal experiences. Howard Journal of Communications. 2008;19:144–164. doi: 10.1080/10646170801990953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;8:133–142. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.8.2.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shea M, Leong FTL. Working with a Chinese immigrant with severe mental illness: An integrative approach of cognitive-behavioral therapy and multicultural conceptualization. In: Poyrazli S, Thompson CE, editors. International case studies in mental health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, DeBar L, Perrin N, Lynch F, Rosselli F, Kraemer HC. Cognitive behavioral guided self-help for the treatment of recurring binge eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:312–321. doi: 10.1037/a0018915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. In search of cultural competence in psychotherapy and counseling. American Psychologist. 1998;53:440–448. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Walsh T. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traviss GD, Heywood-Everett S, Hill A. Guided self-help for disordered eating: A randomised control trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j. brat.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, Alvidrez J, Bernal G, Escamilla M, Loue S. Research issues for improving treatment of U.S. Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:383–394. doi: 10.1176/ appi.ps.58.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras S, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Gordon KH, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Engel SG. The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:687–705. doi: 10.1002/eat.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CJ, Kim BA, Pituc ST, Atkins M. Poverty, loss, and resilience: The story of Chinese immigrant youth. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:34–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]