Abstract

Objective

To compare hospital-onset C. difficile infection (CDI) incidence rates measured by International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) diagnosis codes and electronically available C. difficile toxin assay results.

Methods

Hospital-onset CDI cases were identified at 5 U.S. hospitals between 07/00-06/06 using 2 surveillance definitions: positive toxin assay results (gold standard) and secondary ICD-9 diagnosis codes for CDI. Chi-square tests were used to compare incidence rates, linear regression models to analyze trends, and the test of equality to compare slopes.

Results

Of 8,670 hospital-onset CDI cases, 38% were identified by both toxin assay and ICD-9 code, 16% by toxin assay alone, and 45% by ICD-9 code alone. Nearly half (47%) of CDI cases identified by ICD-9 code alone were community-onset cases by toxin assay. The hospital-onset CDI rate was significantly higher by ICD-9 codes compared to toxin assays overall (p < 0.001), as well as individually at 3 of the 5 hospitals (p < 0.001 for all). The agreement between toxin assays and ICD-9 codes was moderate, with an overall kappa value of 0.509 and hospital-specific kappa values that ranged from 0.489 to 0.570. Overall, the annual increase in CDI incidence was significantly greater for rates determined by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays overall (p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Although ICD-9 codes appear to be adequate for measuring the overall CDI burden, use of the C. difficile ICD-9 code without presence on admission classification are not an acceptable surrogate for hospital-onset CDI surveillance.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, surveillance, administrative data

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile is the most commonly recognized cause of infectious diarrhea in hospitalized patients. Several reports suggest that the incidence and severity of C. difficile infection (CDI) have been increasing in recent years, due in part to transmission of a single, fluoroquinolone-resistant epidemic strain with enhanced virulence characteristics.1-7 Given the increase in the incidence and severity of CDI, a surveillance system to track rates of CDI is necessary. In the absence of a national surveillance system, International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes assigned at hospital discharge have been used as a surrogate. Current national CDI estimates are based on a national probability sample of patient discharge records from nonfederal, short-stay hospitals.8 Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services identified the reduction of endemic CDI rates as a high priority goal in their Action Plan to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections, and proposed ICD-9 codes as a metric to measure CDI case rates.9 Surveillance with administrative discharge data is advantageous because the data are inexpensive to obtain and readily available at all hospitals in the U.S., thus providing a nationally representative method for tracking CDI rates.10, 11 Conversely, case ascertainment using current surveillance definitions (i.e., symptoms of diarrhea or toxic megacolon combined with a positive result of a laboratory assay and/or endoscopic or histopathologic evidence of pseudomembranous colitis), the gold standard for CDI surveillance, is labor-intensive and expensive because it requires both microbiology results and medical chart review.12

Data from two single-institution studies suggest that ICD-9 codes may be an acceptable surrogate for tracking the overall CDI burden in the absence of toxin testing results.13, 14 However, no multicenter studies have been conducted to evaluate CDI surveillance by ICD-9 codes, nor have there been any studies reporting more than one year of data. There have not been any investigations of the ability of ICD-9 codes to track rates of hospital-onset CDI.

The objective of this study was to compare hospital-onset CDI incidence rates measured by ICD-9 diagnosis codes to CDI rates measured by electronically available C. difficile toxin assay results, the gold standard, at multiple healthcare facilities during a 6-year study period. We sought to determine the utility of ICD-9 codes for overall hospital-onset CDI surveillance, as well as for intra-hospital and inter-hospital comparisons of hospital-onset CDI incidence. In addition, we evaluated the impact of surveillance by ICD-9 codes on the proportion of hospital-onset CDI relative to community-onset and recurrent CDI.

METHODS

The study population included all adult patients admitted and discharged between July 1, 2000 and June 30, 2006 at five hospitals participating in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention Epicenters program. These hospitals included Barnes-Jewish Hospital (St. Louis, MO), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA), The Ohio State University Medical Center (Columbus, OH), Stroger Hospital of Cook County (Chicago, IL), and University of Utah Hospital (Salt Lake City, UT). Eligibility was limited to patients ≥ 18 years of age. Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review boards of the CDC and all participating centers.

Retrospective data were collected from hospital medical informatics databases and included dates of hospital admission, discharge, and stool collection as well as C. difficile toxin assay results and the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) discharge diagnosis code for CDI (008.45). Medical coders are trained to assign this code to hospital admissions with medical record documentation by the treating clinician of gastroenteritis or colitis due to C. difficile; positive laboratory tests alone are not sufficient to warrant application of the code. 008.45 is the only ICD-9-CM code specific for CDI.15

Case Definitions

Hospital-onset CDI cases, defined as patients with non-recurrent CDI with onset > 48 hours after admission, were identified using two surveillance definitions: positive toxin assay results and ICD-9 diagnosis codes for CDI. Patients identified by a positive toxin assay were not considered to be a hospital-onset CDI case if the first positive toxin assay occurred ≤ 48 hours from admission or the patient had a positive toxin assay in the previous 8 weeks (recurrent CDI). Because primary ICD-9 codes for CDI suggest that CDI was the primary reason for admission, patients identified by an ICD-9 code for CDI were not considered to have hospital-onset CDI if the ICD-9 diagnosis code was the primary discharge code. Also, since cases of CDI that occur in the same patient within 8 weeks following a previous case are considered recurrent, hospitalizations identified by an ICD-9 code for CDI were considered recurrent if an ICD-9 code for CDI had been assigned to a hospitalization for the same patient in the previous 8 weeks.

Community-onset CDI cases were defined as patients with non-recurrent CDI and a positive toxin assay ≤ 48 hours from admission (by the toxin assay definition) or a primary ICD-9 diagnosis code for CDI (by the ICD-9 code definition). CDI cases were attributed to the month of stool collection for the positive toxin assay definition and to the month of hospital discharge for the ICD-9 code definition. For patients with multiple positive toxin assays during a single hospitalization, only the first positive toxin assay was included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Monthly CDI rates per 1,000 discharges were calculated for each surveillance definition (i.e., positive C. difficile toxin assay and ICD-9 code). Discharges, rather than patient days, were used for the denominator because date of CDI onset was not known for ICD-9 codes and ICD-9 codes are assigned at discharge. Rates were compared with chi-square tests, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Linear regression was used to estimate the annual change in CDI incidence and the test of equality was used to compare the slopes. Kappa (κ) statistics were calculated to measure the agreement between C. difficile toxin assay results and ICD-9 codes. Data from hospital D was incomplete for the first 14 months and the last 14 months of the study period; therefore, these months were excluded from the analysis for hospital D. All tests were two-tailed and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Epi Info, version 6, SPSS for Windows, version 14.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), and Stata, version 9.2.

RESULTS

The number of hospital discharges varied by hospital (range, 84,984 - 318,847), with a total of 930,692 hospital discharges during the 6-year study period (Table 1). C. difficile toxin assays were positive in 8,376 (0.9%) discharges, of which 3,435 (41%) were identified within 48 hours of admission (i.e., consistent with community-onset CDI) and 4,941 (59%) were identified more than 48 hours after admission (i.e., consistent with hospital-onset CDI). ICD-9 codes for CDI were assigned to 9,578 (1%) discharges, of which 1,339 (14%) were primary ICD-9 codes and 8,239 (86%) were secondary ICD-9 codes. Seven percent (n = 624) of CDI cases identified by toxin assays had a prior positive toxin assay in the previous 8 weeks and 13% (n = 1,237) of CDI cases identified by ICD-9 codes had an ICD-9 code assigned to a hospitalization in the previous 8 weeks. Compared to toxin assay results, the sensitivity and specificity of ICD-9 codes for tracking the overall CDI burden were 78.1% and 99.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Method of Clostridium difficile infection case identification among 930,692 hospital discharges at 5 hospitals.

| Toxin Assay (+) | Toxin Assay (-) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 (+) | 6,545 | 3,033 | 9,578 |

| ICD-9 (-) | 1,831 | 919,283 | 921,114 |

| Total | 8,376 | 922,316 | 930,692 |

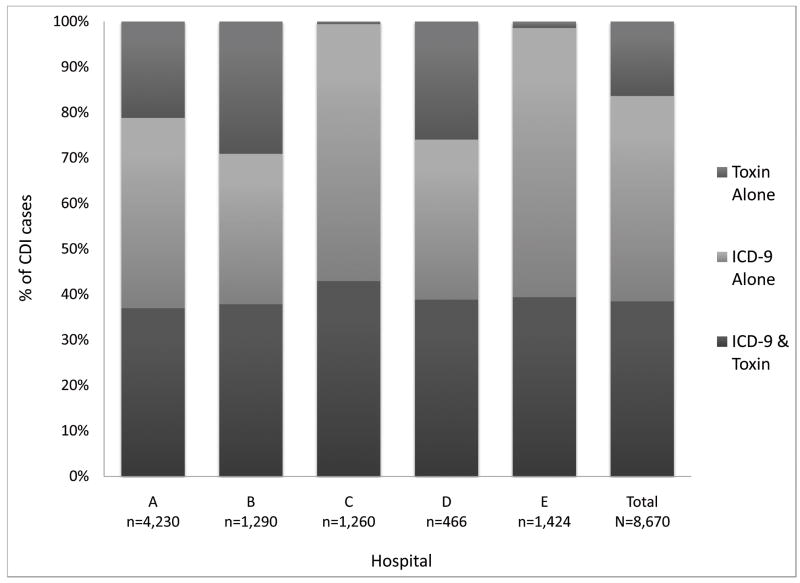

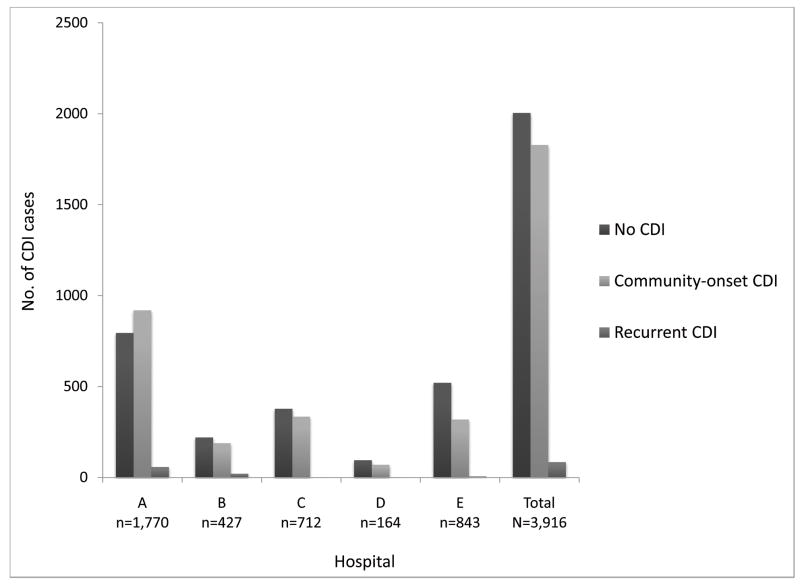

Among 8,670 hospital-onset CDI cases identified during the study period by ICD-9 code and/or toxin assay, 3,335 (38%) CDI cases were identified by both toxin assay and ICD-9 code, 1,419 (16%) CDI cases were identified by toxin assay alone, and 3,916 (45%) CDI cases were identified by ICD-9 code alone (Figure 1). ICD-9 codes identified 53% more hospital-onset CDI cases than toxin assays. The agreement between toxin assays and ICD-9 codes was moderate, with an overall kappa value of 0.509, and hospital-specific kappa values ranging from 0.489 to 0.570. Compared to the toxin assay definition, the ICD-9 code definition classified a significantly higher proportion of CDI cases as hospital-onset CDI (76% vs. 57%, p < 0.001) than community-onset CDI or recurrent CDI. Of the 3,916 discordant cases classified as hospital-onset CDI by the ICD-9 code definition but not by the toxin assay definition, the toxin assay definition classified 1,828 (47%) as community-onset CDI, 84 (2%) as recurrent CDI, and 2,004 (51%) without CDI (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Case identification of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection cases by hospital. The hospital-specific kappa values were as follows: hospital A (.489), hospital B (.494), hospital C (.570), hospital D (.499), and hospital E (.527). The overall kappa value was 0.509.

Figure 2.

Classification of Clostridium difficile infection cases by the toxin assay definition for the 3,916 discordant admissions classified as hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection by the ICD-9 code definition alone.

Table 2 presents hospital-onset CDI rates by surveillance definition. Overall, the hospital-onset CDI rates were significantly higher by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays (7.8 vs. 5.1 cases per 1,000 discharges; p < 0.001). The hospital-onset CDI rates for the entire study period were higher by ICD-9 codes compared to toxin assays at all 5 hospitals, with significant differences at 3 out of 5 hospitals (p < 0.001 for hospitals A, C, and E) and a marginally significantly difference at a fourth hospital (p = 0.092 for hospital D). Figures 3 and 4 present annual hospital-onset CDI rates by surveillance definition, overall and stratified by hospital, respectively. Across hospitals, there was significant variation in the additional increase of hospital-onset CDI cases identified by ICD-9 codes compared to toxin assays (test of equality p < 0.001). ICD-9 codes identified 6% more CDI cases than toxin assays at hospital B, 14% more CDI cases at hospital D, 36% more CDI cases at hospital A, 129% more CDI cases at hospital C, and 142% more CDI cases at hospital E.

Table 2.

Hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection rates by surveillance with ICD-9 codes and toxin assays.

| Hospital | No. of discharges | ICD-9 codes | Toxin Assay | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No. of CDI cases | CDI rate per 1,000 discharges | No. of CDI cases | CDI rate per 1,000 discharges | |||

| A | 318,847 | 3,334 | 10.5 | 2,460 | 7.7 | <.001 |

| B | 110,437 | 915 | 8.3 | 863 | 7.8 | .219 |

| C | 254,073 | 1,253 | 4.9 | 548 | 2.2 | <.001 |

| D | 84,984 | 345 | 4.1 | 302 | 3.6 | .092 |

| E | 162,351 | 1,404 | 8.6 | 581 | 3.6 | <.001 |

| Total | 930,692 | 7,251 | 7.8 | 4,754 | 5.1 | <.001 |

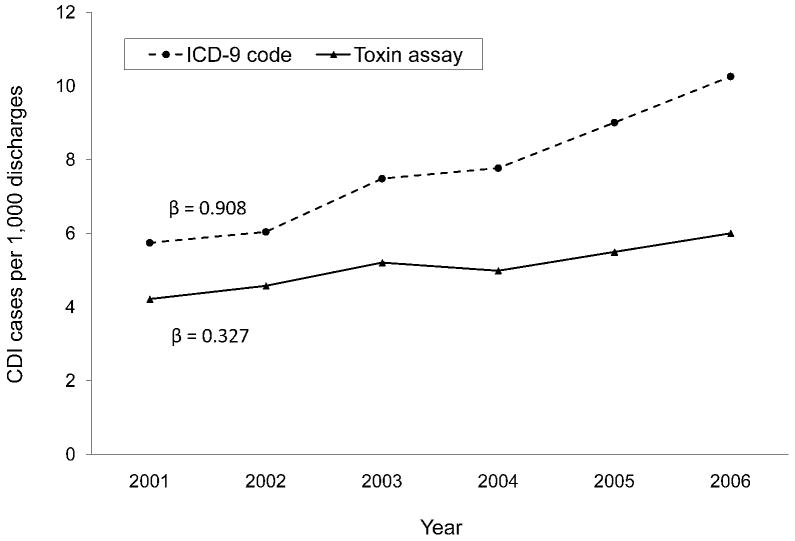

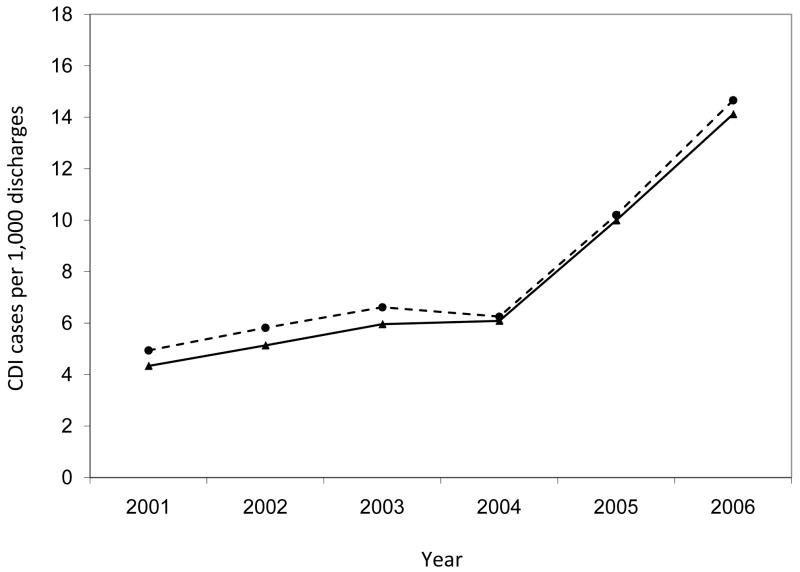

Figure 3.

Annual rates of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection by surveillance definition, a global assessment. The annual increase in incidence was significantly higher for the rates by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays (β = 0.908 vs. β = 0.327; p = 0.006).

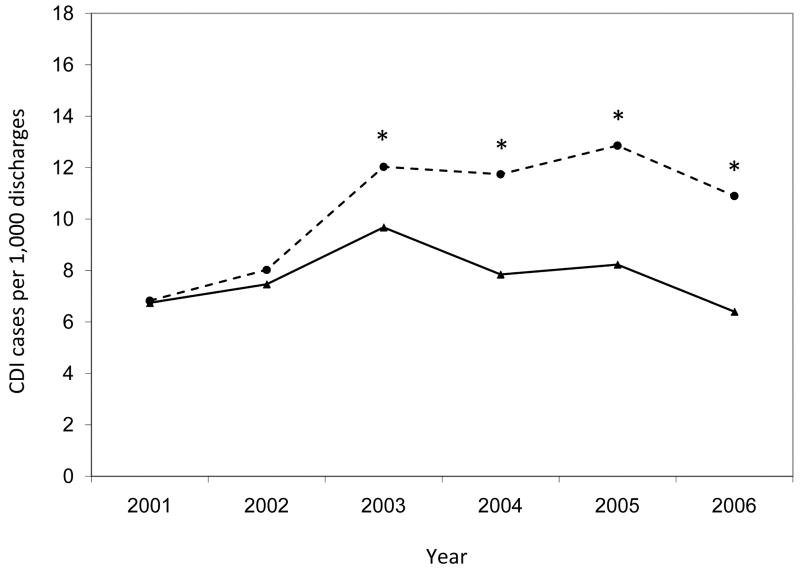

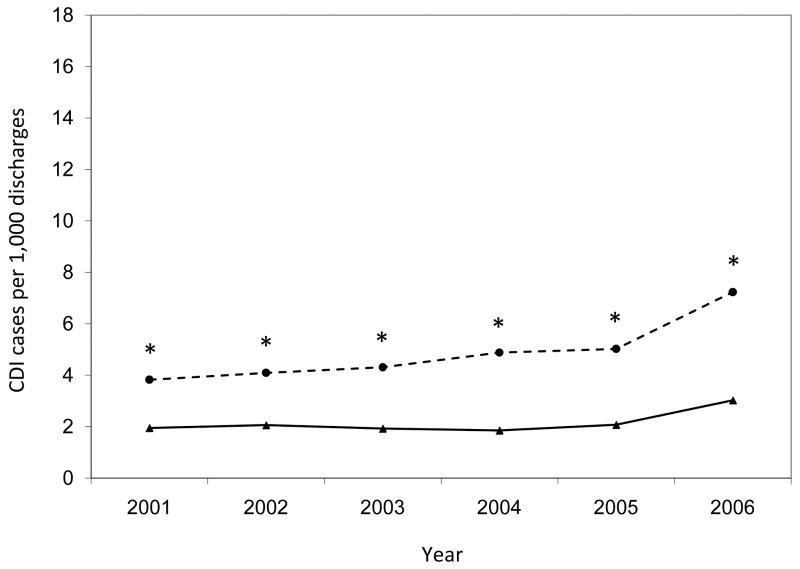

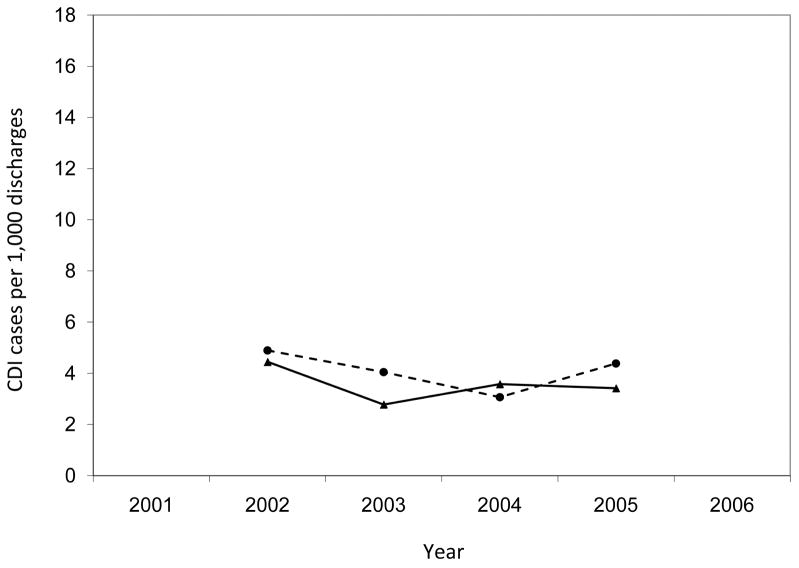

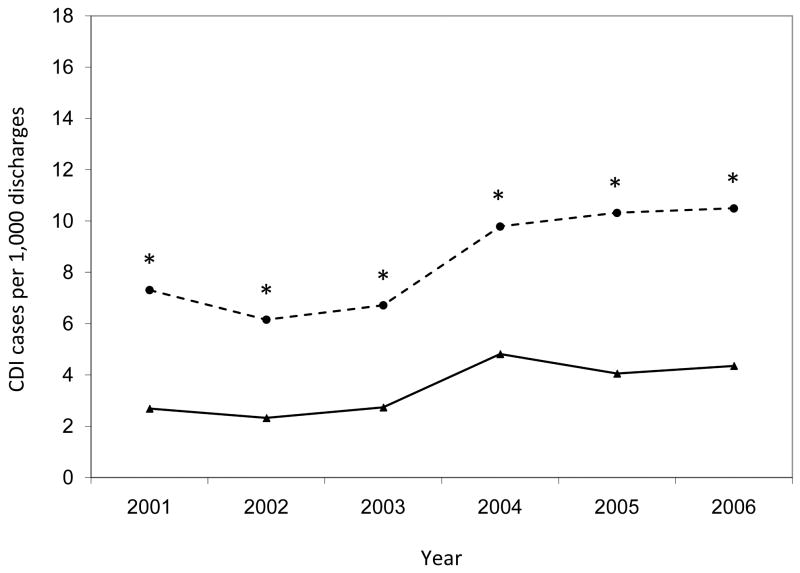

Figure 4.

Annual rates of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection by surveillance definition, stratified by hospital. Asterisks indicate significantly higher annual CDI rates by ICD-9 codes compared to toxin assays (p < 0.001). CDI, Clostridium difficile infection.

The annual hospital-onset CDI rates were also significantly higher by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays for the entire study population (p < 0.001 for each year) (Figure 3). Within hospitals, the number of years with significant differences in hospital-onset CDI rates by surveillance definition varied (range, 0 – 6) (Figure 4). Of the 28 annual time points in the analysis (i.e., 6 years for each hospital with the exception of 4 years for Hospital D), half of the time-points (n = 14) had hospital-onset CDI rates that differed significantly by surveillance definition, after correction for multiple comparisons (p < 0.001 for all). Hospitals C and E had significantly higher rates by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays for every year of the 6-year study period. Hospital A had significantly higher rates by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays for the last four years of the study period. At hospitals B and D, the hospital-onset CDI rates did not differ by surveillance definition for any year.

While the overall annual rates increased almost every year of the study period regardless of surveillance definition, the annual increase in incidence was significantly higher for the rates by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays (β = 0.908 vs. β = 0.327; p = 0.006; Figure 3). At three hospitals, the annual increase in CDI incidence was higher for rates by ICD-9 codes than by toxin assays (Figure 4), with significant differences at hospitals A (β = 0.990 vs. β = -0.035; p = 0.014) and C (β = 0.583 vs. β = 0.151; p = 0.025) and a non-significant difference at hospital E (β = 0.900 vs. β = 0.447; p = 0.129).

DISCUSSION

The results of this multicenter study of patients admitted to five geographically diverse academic medical centers suggest that ICD-9 codes may be an adequate surrogate for tracking the overall CDI burden but are of little to no use for tracking hospital-onset CDI incidence compared to toxin assay results. Consistent with previous reports, the sensitivity and specificity of ICD-9 codes for tracking the overall CDI burden were 78.1% and 99.7%, respectively, suggesting that ICD-9 codes are an adequate surrogate for tracking CDI prevalence compared to toxin assay results. However, ICD-9 codes only demonstrated moderate agreement with toxin assay results for identification of patients with hospital-onset CDI. ICD-9 codes significantly over-reported the incidence of hospital-onset CDI compared to toxin assay results, and the degree to which hospital-onset CDI incidence was over-reported by ICD-9 codes varied by year and by hospital. In addition, the annual increase in the incidence of hospital-onset CDI was greater by ICD-9 codes than the annual increase by toxin assays overall and at three of the individual hospitals. These results indicate that ICD-9 codes would not have been useful for overall hospital-onset CDI surveillance, nor would they be useful for intra-hospital or inter-hospital comparisons of CDI incidence during the study period.

Previous studies of CDI surveillance using ICD-9 codes have focused on the overall CDI burden rather than hospital-onset CDI. Data from two single-institution studies suggest that ICD-9 codes are an acceptable surrogate for tracking the overall CDI burden in the absence of toxin testing results.13, 14 In a cohort of patients hospitalized during 2003 at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, there was very good agreement between ICD-9 codes and toxin assay results for CDI case ascertainment (κ = 0.72).13 In this study we reported that ICD-9 codes had a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 99.7%. These results were remarkably similar to a study by Scheurer and colleagues of patients hospitalized in 2004 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.14 These investigators reported a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 99% for CDI surveillance by ICD-9 codes compared to positive toxin assays. In our current study, the sensitivity (78.1%) and specificity (99.7%) of ICD-9 codes for tracking the overall CDI burden were consistent with previous reports. This suggests that ICD-9 codes may be an adequate surrogate for tracking overall CDI prevalence compared to toxin assay results. It is possible that the disparity in the ability of ICD-9 codes to track overall CDI versus hospital-onset CDI can be explained by an inherent limitation of ICD-9 code-based surveillance: ICD-9 codes are assigned to the date of discharge rather than the date of diagnosis, and thus do not give any information regarding the date of CDI onset. In our study, 47% of the cases discordantly classified as hospital-onset CDI by the ICD-9 code definition but not by the toxin assay definition had their first positive toxin assay within 48 hours of admission, and therefore were community-onset CDI cases according to the gold standard definition. In the future, present on admission codes, which became mandatory for Medicare patients discharged on or after October 1, 2007 (i.e., after the study period), may add precision to ICD-9 code-based CDI surveillance by providing a mechanism to distinguish pre-existing conditions and ultimately reducing misclassification of community-onset CDI cases.16

Chart review was not performed for this study, however prior studies have used chart review to investigate discrepancies in CDI case ascertainment between toxin assay and ICD-9 code surveillance definitions. In our study, 3,916 (45%) hospital-onset CDI cases were identified by the ICD-9 code surveillance definition but not by the toxin assay surveillance definition. 1,912 (49%) of these cases were misclassified as hospital-onset CDI by ICD-9 codes because they were identified as community-onset CDI (n=1,828) or recurrent CDI (n=84) by toxin assay results. There were no corresponding positive toxin assays for the remaining 2,004 (51%) of these cases. Scheurer et al. performed chart review for the 35 patients with an ICD-9 code but without a positive toxin assay in their study and reported that all of these patients had a prior history of CDI documented in their past medical history but did not have active disease during the hospital stay.14 In our previous study at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, 142 (59%) patients with an ICD-9 code but without a positive toxin assay had a past history of CDI.13 In addition, 137 (57%) patients with an ICD-9 code but without a positive toxin assay had at least one order for toxin testing, and 130 (95%) of these had at least one negative toxin test. It is possible that many of the patients in this study identified as having hospital-onset CDI without a corresponding toxin assay had only a past history of CDI. Alternatively, some of these cases could have occurred among patients with diarrhea whose physicians noted a high clinical suspicion of CDI, but who never had a positive toxin assay.

In our current study, 16% of the hospital-onset CDI cases were identified by the toxin assay surveillance definition alone. This discrepancy may be due, in part, to pending toxin assay results at discharge. We previously reported that admissions with only a positive toxin assay and no ICD-9 code were more likely than concordant admissions to have their first positive toxin assay within 48 hours of discharge (44% vs. 14%, p < 0.01).13 In our current study, the median duration between first positive toxin assay and hospital discharge was significantly shorter for admissions with only a positive toxin assay compared to concordant admissions (4 vs. 9 days, Mann-Whitney U p < 0.001). The first positive stool sample was collected within 2 days of discharge for 541 (38%) admissions with a positive toxin only compared to 357 (11%) concordant admissions (p < 0.001). For these admissions, toxin assay results may not yet have been back at the time of discharge and therefore not noted in the physician’s discharge summary for medical coders to capture.

There are several additional limitations to ICD-9 code-based surveillance for hospital-onset CDI. First, the retrospective nature of administrative data causes a time lag in code-assignment since ICD-9 codes are assigned after patients are discharged from the hospital. Second, discharge diagnosis codes reflect conditions diagnosed or treated during the entire admission but do not give information regarding the location or date of CDI onset. Therefore, ICD-9 code-based surveillance cannot be used for ward-level surveillance. Lastly, CDI is currently slated for Phase III of CMS non-reimbursable diagnoses. This may impact the utility of ICD-9 codes for conducting CDI surveillance if the frequency of hospital-onset CDI coding is altered.

This study was limited to academic medical centers located in urban areas. Although medical coding practices are theoretically standardized across institutions, differences in coding practices may exist according to hospital size, location, or teaching status. In addition, there may be differences in patient populations or physician practices at urban, academic medical centers compared to other acute-care settings that influence the likelihood that a patient is diagnosed with CDI or assigned the ICD-9 code for CDI.

Despite these limitations, the utilization of ICD-9 codes is potentially valuable for CDI surveillance because the data are readily available from hospital billing databases and provide a universal method of surveillance. ICD-9 codes appear to be adequate for measuring the overall CDI burden, however, our data from 2000-2006 indicate that ICD-9 codes are not an adequate substitution for toxin assay results for surveillance of hospital-onset CDI. The recent implementation of present on admission code assignment offers a potential mechanism to differentiate community-onset CDI from hospital-onset CDI, and to ultimately improve the accuracy of ICD-9 code-based surveillance. Additional work is needed to evaluate the impact present on admission codes have on hospital-onset CDI surveillance in multiple acute-care settings before ICD-9 codes can be considered for hospital-onset CDI surveillance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kimberly Reske for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (UR8/CCU715087-06/1 and 5U01C1000333 to Washington University, 5U01CI000344 to Eastern Massachusetts, 5U01CI000328 to The Ohio State University, 5U01CI000327 to Stroger Hospital of Cook County/Rush University Medical Center, and 5U01CI000334 to University of Utah) and the National Institutes of Health (K12RR02324901, K24AI06779401, K01AI065808 to Washington University). Findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Preliminary data were presented in part at the 19th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, San Diego, CA (March 19-22, 2009).

Potential conflicts of interest: E.R.D. has served as a consultant to Merck, Salix, and Becton-Dickinson and has received research funding from Viropharma. D.S.Y. has received research funding from Sage Products, Inc. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363–72. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muto CA, Pokrywka M, Shutt K, et al. A large outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated disease with an unexpected proportion of deaths and colectomies at a teaching hospital following increased fluoroquinolone use. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:273–80. doi: 10.1086/502539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466–72. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pepin J, Saheb N, Coulombe MA, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolones as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1254–60. doi: 10.1086/496986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archibald LK, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Secular trends in hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile disease in the United States, 1987-2001. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1585–9. doi: 10.1086/383045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:409–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.051064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [04/09/09];HHS Action Plan to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2010.0128. http://www.hhs.gov/ophs/initiatives/hai/prevtargets.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Iezzoni L. Coded Data from Administrative Sources. In: Iezzoni L, editor. Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes. 3. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press; 2009. pp. 83–138. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Legler JM. Assessing comorbidity using claims data: an overview. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-26–35. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald LC, Coignard B, Dubberke E, Song X, Horan T, Kutty PK. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:140–5. doi: 10.1086/511798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubberke ER, Reske KA, McDonald LC, Fraser VJ. ICD-9 codes and surveillance for Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1576–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheurer DB, Hicks LS, Cook EF, Schnipper JL. Accuracy of ICD-9 coding for Clostridium difficile infections: a retrospective cohort. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:1010–3. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ICD-9-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting. Services DoHaH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. [03/01/09];Hospital-Acquired Conditions (Present on Admission Indicator) http://www.cms.hhs.gov/hospitalacqcond/