Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects more than 30% of Americans, and with increasing problems of obesity in the United States, NAFLD is poised to become an even more serious medical concern. At present, accurate classification of steatosis (fatty liver) represents a significant challenge. In this study, the use of high-frequency (8 to 25 MHz) quantitative ultrasound (QUS) imaging to quantify fatty liver was explored. QUS is an imaging technique that can be used to quantify properties of tissue giving rise to scattered ultrasound. The changes in the ultrasound properties of livers in rabbits undergoing atherogenic diets of varying durations were investigated using QUS. Rabbits were placed on a special fatty diet for 0, 3, or 6 weeks. The fattiness of the livers was quantified by estimating the total lipid content of the livers. Ultrasonic properties, such as speed of sound, attenuation, and backscatter coefficients, were estimated in ex vivo rabbit liver samples from animals that had been on the diet for varying periods. Two QUS parameters were estimated based on the backscatter coefficient: effective scatterer diameter (ESD) and effective acoustic concentration (EAC), using a spherical Gaussian scattering model. Two parameters were estimated based on the backscattered envelope statistics (the k parameter and the μ parameter) according to the homodyned K distribution. The speed of sound decreased from 1574 to 1565 m/s and the attenuation coefficient increased from 0.71 to 1.27 dB/cm/MHz, respectively, with increasing fat content in the liver. The ESD decreased from 31 to 17 μm and the EAC increased from 38 to 63 dB/cm3 with increasing fat content in the liver. A significant increase in the μ parameter from 0.18 to 0.93 scatterers/mm3 was observed with increasing fat content in the liver samples. The results of this study indicate that QUS parameters are sensitive to fat content in the liver.

Keywords: Quantitative ultrasound, Attenuation coefficient, Backscatter coefficient, Envelope statistics, Fatty liver

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease and leads to more severe liver conditions, such as hepatocarcinomas, cirrhosis, or complete liver failure (Wieckowska and Feldstein 2008). Even though biopsy is the current gold standard for diagnosis of diffuse liver disease, this technique is not without limitations. First, liver biopsy suffers from sampling problems: liver biopsies sample as little as 1/50,000 of the total mass of the liver, often resulting in insufficient information for a definitive diagnosis (Janiec et al. 2005; Ratziu et al. 2005; Merriman et al. 2006). Second, it is an invasive method involving certain risks and added stress and expense. Finally, the histologic evaluation is subjective and dependent on the experience of the pathologist. Therefore, there is a medical need to develop noninvasive techniques that can robustly quantify diffuse liver disease such as NAFLD.

Ultrasonic imaging has been explored for many years for its ability to detect and characterize liver disease (Tchelepi et al. 2002; Mishra and Younossi 2007). Although conventional ultrasound has been successful in diagnosing some liver conditions, the use of this technique for liver disease diagnosis has several limitations. Current conventional ultrasonic techniques do not allow for quantification of the degree of fatty liver. The effectiveness of ultrasound for liver disease detection is reduced in patients who are morbidly obese (sensitivity is reduced to below 40%) (de Almeida et al. 2008). For conventional ultrasound to detect steatosis, the degree of fat infiltration in the liver must be above 30% (Fishbein et al. 1997; Mehta et al. 2008; Dasarathy et al. 2009). Moreover, ultrasonic imaging is highly subjective and depends on the expertise and experience of the operator (Zwiebel 1995). Researchers have investigated the liver-kidney contrast to quantify liver fat content using the ultrasound hepatic/renal ratio and the hepatic attenuation rate from ultrasound hepatic and right kidney images (Xia et al. 2011). However, this technique still needs standardization and further testing in a clinical setting.

Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) techniques have been widely used to characterize tissue microstructure and to infer the acoustical properties of the tissue. Measurements of speed of sound (Goss et al. 1978; Techavipoo et al. 2004) can provide a means of tissue characterization. The mean sound speed in soft tissue varies from approximately 1420 m/s in breast fat to 1640 m/s in muscle tissues (Goss et al. 1978; Duck 1990). Bamber and Hill (1981) reported higher mean sound speed in excised normal liver than in fatty human livers. In another in vivo study, researchers reported higher sound speed in normal liver than in fatty liver without fibrosis from human (Chen et al. 1987).

Spectral-based QUS parameters, such as attenuation and the backscatter coefficient (BSC) can be estimated from backscattered signals, which can be used to differentiate between normal and fat-infiltrated livers. QUS techniques have been used to quantify properties of the liver for both in vitro and in vivo studies (Bamber and Hill 1981; Fei and Shung 1985; Wear et al. 1995). Afschrift and coworkers reported increases in attenuation as the degree of steatosis exceeded 5 vol% compared to healthy liver (Afschrift et al. 1987). In a clinical trial, O’Donnell and Reilly (1985) observed higher BSCs in subjects with liver cirrhosis than in normal livers. The authors did not observe any significant differences in attenuation between normal livers and livers with cirrhosis. In an in vivo study, Wilson et al. (1984) reported higher attenuation in livers with cirrhosis and fatty changes compared to normal livers. Researchers have examined the use of attenuation and BSCs to monitor the stages of the liver remodeling in mice (Gaitini et al. 2004; Guimond et al. 2007). Lu and coworkers demonstrated that the BSC and attenuation in patients with diffuse liver disease were higher than in patients with healthy livers (Lu et al. 1999). Suzuki and coworkers observed that the ultrasonic attenuation depends on fatty infiltration of the liver and to a lesser extent on fibrosis (Suzuki et al. 1992).

Recent studies have examined the use of envelope statistics to characterize fibrotic liver (Tsui et al. 2009; Igarashi et al. 2010; Yamaguchi and Hachiya 2010; Ho et al. 2012). In these studies, different models for describing the envelope statistics of backscattered ultrasound (Rayleigh, Nakagami, and the K distribution) were used to characterize successfully a liver as either fibrotic or normal. In a similar study, researchers used the textural features of ultrasound B-mode images to grade hepatic steatosis in children with suspected NAFLD (Shannon et al. 2011).

Because QUS parameters have provided a unique set of descriptors to classify tissues, it is of interest to quantify how these parameters change in a liver with varying degrees of fatty infiltration. In this study, several QUS parameters, such as sound speed, attenuation, and BSC, were estimated in comparison to lipid content in fresh rabbit liver samples. Two parameters were estimated from the BSC: effective scatterer diameter (ESD) and effective acoustic concentration (EAC); and two parameters were estimated from the envelope statistics: the k parameter and the μ parameter. In subsequent sections, the experimental methods used to quantify the changes in QUS parameters versus lipid content are described. The experimental results from fresh rabbit liver samples are provided in a later section. Finally, some conclusions regarding the study are offered.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Liver samples

Fresh liver samples were extracted from male New Zealand White rabbits acquired from Myrtle’s Rabbitry (Tompson’s Station, TN). The rabbits had been on a special fatty diet (King et al. 2009). The basal diet contained 10% fat, 1% cholesterol, 0.11% magnesium, 14% protein, and 54% carbohydrates (1811279, 5TZB, Purina Test Diet, Purina, Richmond, IN). A group of 5 rabbits was put on the fatty diet for 3 weeks and another group of 5 rabbits was put on the fatty diet for 6 weeks. A third group of 4 rabbits consumed a standard chow diet (2031, Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) and was used as a control for the study. Rabbits were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 diets. Water was given ad libitum and 140 g of food was given daily to the rabbits. The feed intake was measured daily and rabbit weights were done weekly. The animals were housed individually in standard stainless steel cages at normal room temperature and light cycles. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Ultrasonic experiments were conducted within 15 min of the removal of the liver from the body. Bamber et al. (1977) observed insignificant changes in attenuation and significant changes in mean backscatter amplitude during the several hours after excision. The short time between the removal of livers from the rabbits and the scanning by ultrasound allowed us better control of the biologic degradation of the livers that occurs over the hours after extraction.

Ultrasonic methods

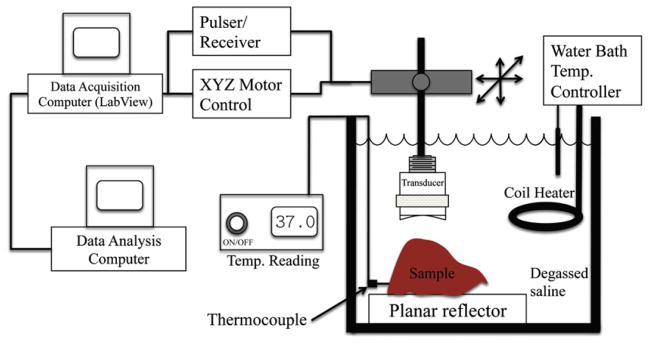

A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 1. The sample was completely submerged in 0.9% degassed saline solution and scanned with 20 MHz single-element transducers (Olympus, Waltham, MA) with a bandwidth of 8 to 25 MHz and a diameter of 0.635 cm. An f/4 transducer was used for liver samples extracted from rabbits that were on the 0 and the 3-week fatty diet, and an f/3 transducer was used for the livers that had experienced the 6-week fatty diet. The transducer was operated in pulse-echo mode using a Panametrics 5900 pulser/receiver (GE Panametrics, Waltham, MA); the echo signals were recorded and digitized with a 14 bit, 200 MHz A/D card (UF3-4142, Strategic Test, Woburn, MA) and downloaded to a computer for postprocessing. The sampling rate used to digitize the received signals was 200 MHz. In an experiment, the sample was held stationary and the transducer was moved using a computer-controlled micropositioning system (Daedal, Harrisburg, PA).

Fig. 1.

Experiment setup.

For QUS analysis, rf signals backscattered from the samples were recorded. A step size of 300 μm was used between consecutive scan lines (approximately 1 full beam width). The beam widths for the f/3 and f/4 transducer were 220 μm and 290 μm, respectively, in water at room temperature. Each experiment lasted for approximately 8 to 10 min. The saline bath was maintained at 37°C during the experiments using a coil heater (Waage Electric, Kenilworth, NJ), which was controlled by a temperature-monitoring device (YS172; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH).

Sound speed and attenuation

Sound speed and attenuation were estimated in the liver samples using time of flight and insertion loss methods, respectively (Madsen et al. 1999). To estimate sound speed, arrival times of the received pulses were measured with and without the sample in the saline path between the transducer and the planar reflector. The sound speed in the sample c was computed from

| (1) |

where cf is the speed of sound in the surrounding fluid media, t3 is the propagation time to the reflector measured when no sample is in the sound path, and t1 and t2 are the arrival times of the front wall of the sample and the sample/reflector interface echoes, respectively. The propagation times were estimated using cross-correlation. Using the speed of sound estimated from eqn 1, the sample thickness, d, was calculated. Due to changes in attenuation in the sample and in the water bath, the correlation method will result in lower estimates of sound speed. The attenuation coefficient was estimated using

| (2) |

where d is the thickness of the sample, |F2(f )| and |F3(f )| are the magnitudes of the Fourier transform of the time domain reflected signal from the Plexiglas reflector with and without the sample in the path, respectively.

Backscatter coefficient

Ultrasonic B-mode images of the scanned areas were constructed, and regions of interest (ROIs) in the B-mode images were examined for the spectral content of the backscattered rf echoes. Square-shaped data blocks of size 30λ axially by 30λ laterally (λ is the wavelength at the center frequency of the transducer) were constructed within an ROI. The BSC was estimated from the backscattered rf signals and a reference scan for each data block given by (Chen et al. 1997; Lavarello et al. 2011):

| (3) |

where the backscatter data is gated between (F − Δz/2) and (F+Δz/2), A0 is the aperture area, W(f ) is the normalized power spectrum and Jm(●) is the mth order Bessel function. The reference scan was obtained from a Plexiglas planar reflector located at the focus of the transducer. The normalized power spectrum (Oelze et al. 2002) is given by

| (4) |

where γ0 is the reflection coefficient of the planar reflector, S(f ) is the power spectrum of the gated signal of the nth rf signal, M is the number of gated rf signals, and Sref is the reference power spectrum. Please note that Sn(f ) and Sref(f ) are power spectra obtained after attenuation compensation.

The integrated backscatter coefficient (IBC) was estimated by integrating the BSC in the frequency band of the transducer given by

| (5) |

where N is the total number of data blocks, and f1 and f2 refer to the lower and upper limits of the analysis frequency band (MHz), respectively.

Estimates of the ESD were obtained by using a spherical Gaussian scattering model. In the frequency domain, the normalized theoretic power spectrum is given by (Lizzi et al. 1997; Oelze et al. 2002):

| (6) |

where L is the gate length (mm), q is the ratio of aperture radius to distance from the ROI, f is the frequency (MHz), and 2aeff is the ESD. The ESDs have been related to the size of dominant scatterers in tissues. The quantity, , is termed the EAC and is the product of the number of scattering particles per unit volume (mm3), ρ, and the square of the fractional change in the impedence between the scattering particles and the surrounding medium, zvar = (Z−Z0)/Z0, where Z and Z0 are the acoustic impedances of the scatterers and the surrounding medium, respectively.

Accurate attenuation estimation is needed for unbiased ESD estimates. Here a spherical Gaussian scattering model is used to estimate ESD and EAC by comparing theoretic and experimental BSCs. If incorrect attenuation were used to compensate the experimental power spectrum to estimate BSC, then the biased BSC could be represented by η(f)exp(0.4614Δαzf ), where Δα is the error in attenuation compensation (dB/cm/MHz), assuming attenuation increased linearly with frequency. From eqn 6 and derivation given by Oelze et al (2002), the percentage error propagation in ESD estimates is given by

| (7) |

where N is the total number of frequency points and 2Δaeff is the change in ESD. Similarly, the error in EAC will be proportional to the sixth power of the error in ESD estimates.

Texture parameters

ROIs in the B-mode images were also analyzed using envelope statistics methods. The homodyned K distribution was used to model the amplitude of the envelope from data blocks of size 30λ axially by 30λ laterally in the liver samples (Dutt and Greenleaf 1994; Oelze et al. 2007). The homodyned K distribution yields 2 parameters: the k parameter quantifies the ratio of coherent to incoherent backscattered signal and the μ parameter quantifies the number of scatterers per resolution cell. A method based on level curves was used to estimate homodyned k parameters (Hruska and Oelze 2009). Estimates of the k parameter and the μ parameter were obtained from backscattered envelope signals corresponding to data blocks in the liver samples. Here, the μ parameter is reported as number of scatterers per resolution cell volume. The resolution cell volume is the volume of the point spread function of the imaging system (Sleefe and Lele 1988). The resolution cell volume was calculated as , where λ is the wavelength based on 4 the input wave center frequency and speed of sound in the sample, and PL refers to pulse length of the input wave. Here PL is defined as the duration of the pulse where the amplitude falls from its maximum value by 20 dB.

The correlation coefficient R between lipid content and the different QUS parameters was estimated using

| (8) |

where the angular bracket 〈y〉 is defined as the mean of y, n is the number of ordered pairs of (l1, q1), …, (ln, qn), and the l and q refer to lipid content and QUS parameters, respectively. In addition, the abilities of various QUS parameters to differentiate among degrees of fatty liver, as confirmed by lipid level content, were assessed through a 1-way ANOVA. Statistically significant differences were quantified through p values (<0.05).

Biochemistry methods

The total liver lipids were estimated by following the procedure outlined by King et al. (2009), which is based on a modified Folch method (Folch et al. 1957). The exact same procedure is detailed here for completeness. The sample was placed in chloroform-methanol mixture (1:1), homogenized, and filtered via gravity filtration. A sodium chloride solution (0.29%) was added, vortexed briefly, and then centrifuged. The top layer was discarded, and the interface was washed with 0.29% sodium chloride solution. The remaining solution was placed in a weighed test tube, evaporated, placed in a dessicator for at least 48 h, and weighed to determine total lipids in terms of mg of lipid per gram of liver.

RESULTS

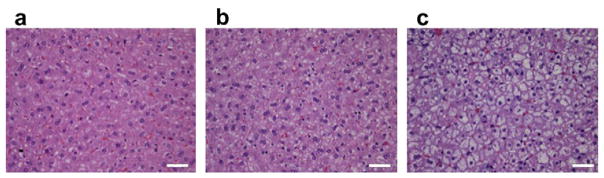

H&E-stained histopathologic images of livers having different lipid levels from animals are shown in Figure 2(a)–(c) at a magnification of 40x. The histopathology images clearly indicate that fat vacuoles accumulated in hepatocytes of the liver samples with higher lipid content, as shown in Figure 2(c). Because the microstructure of the liver tissue changes with lipid content, it was hypothesized that QUS parameters may be able to differentiate between them. Table 1 lists the mean lipid levels estimated for rabbits on the normal diet, on the fatty diet for 3 weeks, and on the fatty diet for 6 weeks. The estimated lipid content values listed in Table 1 are comparable to results obtained by other researchers in fatty rodent livers (O’Brien et al. 1988). Kainuma at al. (2006) observed a significant increase in lipid peroxide in liver tissue from animals on high-cholesterol diets. Other researchers have observed significant increases in hepatic total cholesterol of 38.3 ± 21.5 μg/mg of liver in rabbit liver samples with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis compared to 1.5 ± 0.2 μg/mg of liver in healthy rabbit liver samples (Ogawa et al. 2010). Puri and coworkers reported a threefold increase in total lipids in nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) compared to normal liver samples in humans but did not notice any significant difference in total lipid content between NAFL and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis livers (Puri et al. 2007). Steatosis is defined as livers with greater than 5% total lipid content (Hoyumpa et al. 1975). In the present study, 1.5%, 5.6%, and 13.9% total lipid content were observed in livers from animals on the normal diet, on 3 weeks of the fatty diet, and on 6 weeks of the fatty diet, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Histopathology images of rabbit liver on (a) normal diet; (b) 3 weeks of fatty diet; and (c) 6 weeks of fatty diet. (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

Table 1.

Lipid content in liver samples

| Diet | No. of days on diet | mg lipids/g of liver |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 42 | 15 ± 9 |

| Fat | 21 | 56 ± 22 |

| Fat | 42 | 139 ± 28 |

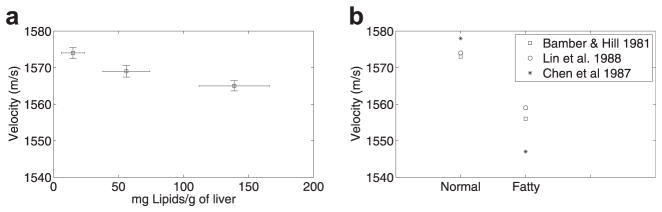

The results of sound-speed estimation obtained in this study are shown in Figure 3(a). For comparison, sound-speed estimates obtained by other researchers from human liver are shown in Figure 3(b). In the present study, sound speed was observed to decrease by less than 0.6% (ie ., from 1574 m/s to 1565 m/s) as lipid content increased. This trend correlates well with previous experimental results. Bamber and Hill (1981) observed speeds of sound of 1573 m/s and 1556 m/s in excised normal and fatty human livers. Lin et al. (1988) reported sound speeds of 1574 ± 10 m/s and 1559 ± 13 m/s in normal and fatty excised human livers obtained from autopsy cases. In an in vivo clinical study, researchers reported sound speed of 1578 ±5 m/s and 1547 ±18 m/s in normal and fatty livers without fibrosis, respectively (Chen et al. 1987). Other studies did not report the fatty content in the livers; therefore, a direct comparison of the expected sound-speed variations cannot be performed. However, the observed trends correlate very well with the trends observed in other studies.

Fig. 3.

(a) Variation of velocity of sound with increasing lipid content; (b) velocity of sound in normal and fatty human livers reported by other researchers.

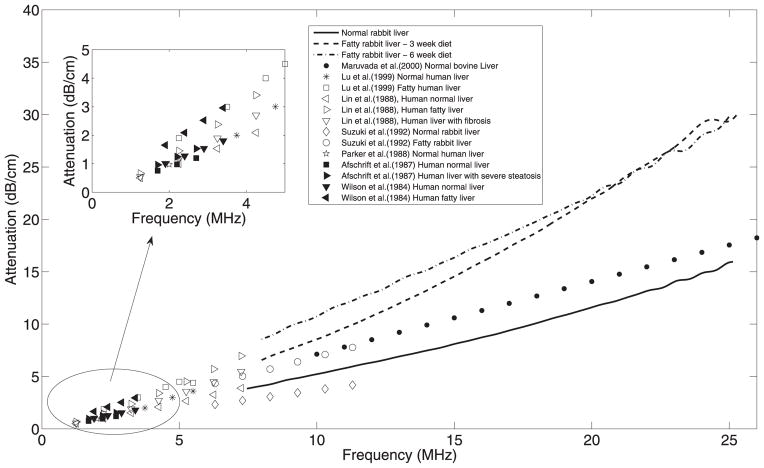

Attenuation estimates obtained in this study from rabbit livers are shown in Figure 4. For comparison, attenuation coefficients in livers obtained by other researchers are also shown in the same figure. In this study, it was observed that attenuation estimates from fatty livers were higher than those in normal livers. However, the attenuation estimates did not monotonically increase with increasing lipid content. These results correlate well with previous reports in the literature. Suzuki and coworkers estimated attenuation coefficients of 0.37 dB/cm/MHz and 0.69 dB/cm/MHz for normal (total lipid content = 45 ± 7.3 mg/g of liver) and fatty (total lipid content =95.7 ±19.2 mg/g of liver) rabbit livers, respectively. The authors used a frequency range of 6.3−11.7 MHz to estimate attenuation coefficients (Suzuki et al. 1992). Lin et al. (1988) reported mean attenuation of 0.58 ± 0.10 dB/cm/MHz and 0.70 ± 0.10 to 1.22 ± 0.52 dB/cm/MHz in normal and fatty livers with different pathologic grades, respectively, in the frequency range of 1.25 to 8 MHz obtained from autopsy cases. Afschrift and coworkers reported a mean attenuation of 0.444 dB/cm/MHz in normal human liver (Afschrift et al. 1987). It is interesting that they reported 0.442 dB/cm/MHz, 0.576 dB/cm/MHz, and 0.566 dB/cm/MHz in livers with light, moderate, or severe steatosis, respectively, which suggest that attenuation does not change linearly after a certain amount of fatty infiltration in the liver (Afschrift et al. 1987), a similar trend observed in the present study. In another in vivo study researchers reported attenuation slopes of 0.53 dB/cm/MHz and 0.87 dB/cm/MHz over the frequency range of 1.9 to 3.5 MHz in normal human livers and human livers with fatty changes (Wilson et al. 1984). Maruvada et al. (2000) reported an attenuation coefficient of 0.69 dB/cm/MHz for bovine livers in the frequency range of 10 to 30 MHz. Other investigators observed mean attenuation values of 1.66 dB/cm and 2.54 dB/cm in healthy and fatty infiltrated human livers in vivo, respectively, at 3 MHz (Lu et al. 1999). Parker et al. (1988) estimated an attenuation coefficient of 0.47 dB/cm/MHz in normal human livers. The attenuation values reported from the present study are within the ranges observed by other researchers in rodent and human livers.

Fig. 4.

Attenuation from liver sample extracted from animals on different diets and values reported by various researchers.

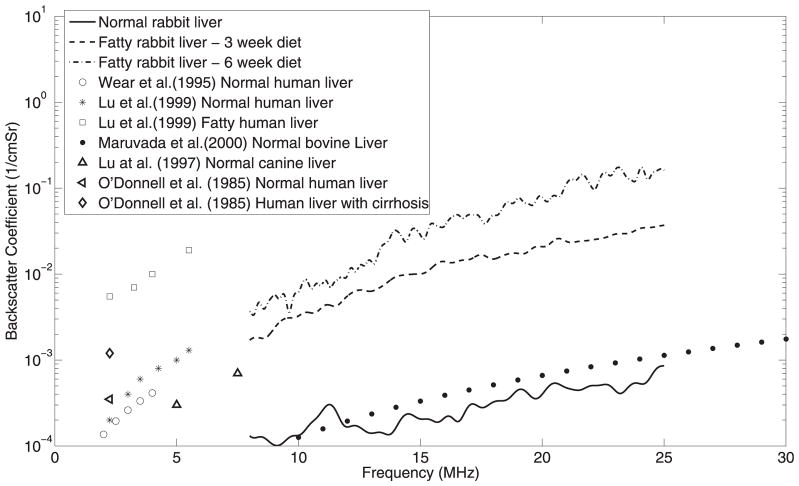

The BSCs were estimated from liver samples extracted from animals on the normal diet, on 3 weeks of the fatty diet, and on 6 weeks of the fatty diet, as shown in Figure 5. The power spectra used to estimate BSCs were compensated using the attenuation values obtained in the current study (Fig. 4). The slope and the magnitude of the BSC changed with increasing lipid content in the liver samples. Differences in the BSC among varying degrees of fatty liver were observed over the whole frequency range, suggesting that in analysis of BSCs, the clinical frequency ranges (<15 MHz) could provide the ability to detect and quantify fatty liver disease. O’Donnell and Reilly (1985) observed a higher BSC in human liver with cirrhosis than in normal liver. Wear et al. (1995) reported a BSC of 2.9 ± 1.8 × 10−4 cm−1 Str−1 at 3 MHz from normal human livers. Other researchers observed average BSCs of 0.5 × 10−3 cm−1 Str−1 and 6.8 × 10−3 cm−1 Str−1 in healthy and fatty infiltrated human livers, respectively, at 3 MHz (Lu et al. 1999). Lu et al. (1997) reported BSC from canine livers as 3 × 10−4 cm−1 Str−1 and 7 × 10−4 cm−1 Str−1 at 5 MHz and 7.5 MHz, respectively. Maruvada et al. (2000) reported BSC of 5 × 10−7f 2.4 in excised normal bovine livers in the frequency (f) range of 10 to 30 MHz. The BSC reported by various researchers are shown in Figure 5. The increasing value of BSC with fatty content correlates well with the general observation that echogenic levels increase with increased steatosis degrees, which is the basis for the hepatic/renal ratio as a screening tool. The IBC is a measure of BSC strength and therefore increases with increasing lipid content, as shown in Table 2. The IBC is a measure of echogenicity in the ultrasound B-mode images and may provide a way to quantify absolute instead of relative liver echogenicity because the hepatorenal index measurement can be compromised when the patient has a diseased right kidney (Webb et al. 2009).

Fig. 5.

Backscatter coefficients from liver samples extracted from animals on different diets and values reported by various researchers.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviations of QUS parameters estimated from liver samples with various lipid contents and their statistical significance

|

|

|

|

|

ESD μm |

|

k |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 ± 9 | 1574 ± 1.5 | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 0.0011 ± 0.0009 | 31.19 ± 0.82 | 37.78 ± 5.73 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | ||||||

| 56 ± 22 | 1569 ± 1.6 | 1.36 ± 0.16 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 24.28 ± 1.53 | 53.77 ± 0.32 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| 139 ± 28 | 1565 ± 1.4 | 1.27 ± 0.02 | 0.027 ± 0.003 | 17.04 ± 1.48 | 62.51 ± 3.29 | 0.48 ± 0.20 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| R | −0.9671 | 0.6639 | 0.9879 | −0.9755 | 0.8813 | −0.8289 | 0.8575 | ||||||

| p value | |||||||||||||

| 0–3 wks | 0.0105 | 0.0026 | 0.0012 | 0.0029 | 0.0049 | 0.2210 | 0.0003 | ||||||

| 0–6 wks | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0020 | 0.1796 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| 3–6 wks | 0.0394 | 0.3766 | 0.0030 | 0.0033 | 0.0102 | 0.1025 | 0.0431 | ||||||

EAC = effective acoustic concentration; ESD = effective scatterer diameter; IBC = integrated backscatter coefficients. 0, control group; 3 and 6 wks, 3 weeks and 6 weeks of fatty diet, respectively.

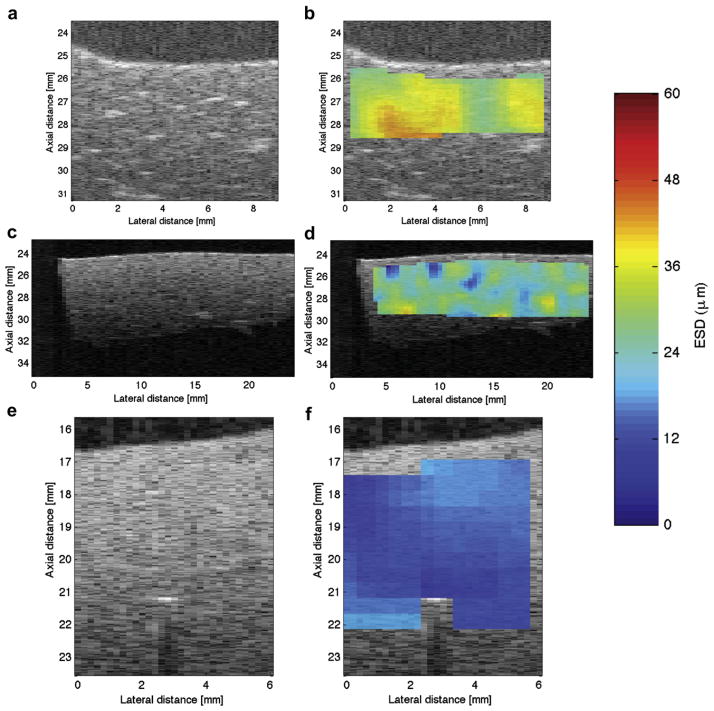

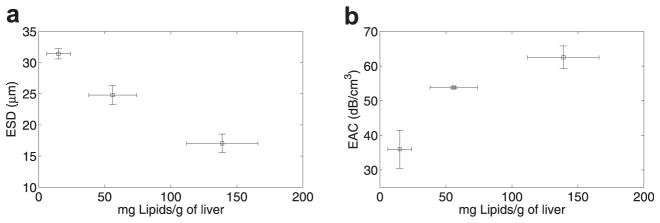

The ESD decreased significantly and EAC increased with increasing lipid content, as shown in Figure 6(a) and (b), respectively. Specifically, the mean ESD was observed to be 30 μm, 25 μm, and 19 μm in liver samples from animals on the normal diet, on 3 weeks of the fatty diet, and on 6 weeks of the fatty diet, respectively. B-mode images and the respective parametric images enhanced by maps of the ESD from liver samples corresponding to the various diets are shown in Figure 7(a)–(f), where the decrease in ESD with increase in fatty diet can be observed. Brighter localized spots on the B-mode images were observed in the normal liver than in the livers with higher lipid content. The spatial variations of ESD were observed to decrease with increasing lipid content, as shown in Figure 7(b),(d), and (f). It should be noted that accurate attenuation estimates are necessary to estimate unbiased ESDs. Using eqn (7), a 0.1 dB/cm/MHz error in attenuation slope estimates will result in a maximum error of 15% in ESD estimates for aeff = 20 μm and z = 1 cm in the frequency band of 8 to 25 MHz.

Fig. 6.

Variation of (a) ESD and (b) EAC with increasing lipid content.

Fig. 7.

(a), (c), and (e) are the B-mode images of liver samples from animals that were on the normal diet, 3 weeks of the fatty diet, and 6 weeks of the fatty diet, respectively. Similarly, the subplots (b), (d), and (f) are the parametric images enhanced by ESD estimates from liver samples taken from animals that were on the normal diet, 3 weeks of the fatty diet, and 6 weeks of the fatty diet, respectively.

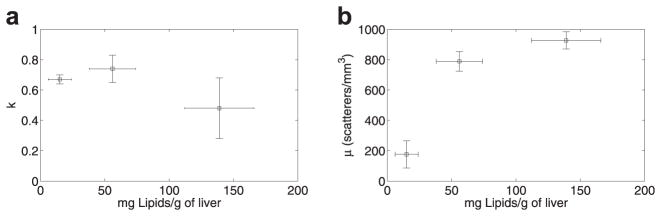

The k parameter estimated from the liver samples of animals on the normal diet and the fatty diet did not provide statistically significant differences, as shown in Figure 8(a). The μ parameter, which is related to the density of scatterers per resolution cell, increased significantly with increasing lipid content, as shown in Figure 8(b).

Fig. 8.

Variation of envelope statistics in terms of (a) the k parameter; and (b) the μ parameter (scatterers per unit volume) with increasing lipid content.

The mean and the standard deviation of the various QUS parameters and the corresponding lipid content are listed in Table 2. The correlation coefficient was estimated considering the mean values of the respective parameters. For example, the mean of the speed of sound versus the respective mean lipid content were used to estimate the correlation coefficient using eqn (8). The correlation between the lipid content levels and the various QUS parameters are listed in Table 2. Here the p values were estimated between livers with various lipid content. For example, p values for 0 to 3 weeks refers to the significance of the QUS parameters for liver samples extracted from animals on the normal diet and on 3 weeks of the fatty diet, respectively. The ESD and μ parameter (p value <0.05) can be used to differentiate among livers extracted from animals on the normal diet, on 3 weeks, and on 6 weeks of the fatty diet. The attenuation coefficient can be used to detect fatty liver (p value <0.05) but could not differentiate between different lipid content in the fatty livers (p value >0.05 for 3 to 6 weeks). Therefore, velocity, attenuation, IBC, ESD, EAC, and the μ parameter could differentiate between normal and fatty livers. Similarly, velocity, IBC, ESD, EAC, and the μ parameter have the potential to grade the degree of fatty liver. The statistical analysis in the present study was conducted using 5 animals per group. This sample size was sufficient to provide statistically significant differences and classification of the grade of fatty liver.

CONCLUSION

Changes in QUS parameter estimates in fresh rabbit liver samples having different lipid content levels are reported. Ultrasonic measurements were taken from liver samples extracted from animals that were on a normal diet, 3 weeks of fatty diet, or 6 weeks of a fatty diet. Using biochemistry methods, lipid content levels in these groups of liver samples were estimated. Various QUS parameters were estimated from these liver samples and correlated with the lipid content levels.

Based on the results, it was observed that some QUS parameters were more sensitive to changes in lipid levels than others. For example, significant increases were observed in attenuation with increases in lipid levels compared to changes in speed of sound. Specifically, the mean attenuation increased by 90% for the liver samples with maximum lipid content compared to normal liver samples.

In this work the effects of attenuation were compensated in the estimate of BSCs. The BSCs were then used to estimate IBC, ESD, and EAC. Significant decreases in ESD and increases in IBC and EAC were observed with increasing lipid content in liver samples. No significant changes in the k parameter were observed with increasing lipid content. However, significant increases in the μ parameter values were observed between normal and fatty liver, and the μ parameter could also differentiate among varying degrees of fatty livers with respect to lipid content. Therefore, envelope statistics may be useful in detecting and characterizing fatty liver disease. Speed of sound, attenuation, and BSC in the current study agree with much of the data reported by other researchers. Most of the previous research had been conducted in the low-frequency regimes, and our results show the characteristics of various QUS parameters in some higher frequency regimes.

The results reported here suggest that changes in QUS parameters may be used to detect and quantify fatty liver diseases. Attenuation, IBC, ESD, EAC, and the μ parameter may be the most sensitive parameters associated with changes in lipid content of the liver.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH Grant R01 EB008992 and R37 EB002641 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). R.J.L. was also funded by PUCP Grant DGI 2012-0149. The authors acknowledge the technical contributions of James P. Blue Jr., Jennifer King, and William D. O’Brien Jr.

References

- Afschrift M, Cuvelier C, Ringoir S, Barbier F. Influence of pathological state on the acoustic attenuation coefficient slope of liver. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1987;13:135–139. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(87)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamber JC, Fry MJ, Hill CR, Dunn F. Ultrasonic attenuation and backscattering by mammalian organs as a function of time after excision. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1977;3:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(77)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamber JC, Hill CR. Acoustic properties of normal and cancerous human liver. I. Dependence on pathological condition. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1981;7:121–133. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(81)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CF, Robinson DE, Wilson LS, Griffiths KA, Monoharan A, Doust BD. Clinical sound speed measurement in liver and spleen in vivo. Ultrason Imaging. 1987;9:221–235. doi: 10.1177/016173468700900401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Phillips D, Schwarz KQ, Mottley JG, Parker KJ. The measurement of backscatter coefficient from a broadband pulse-echo system: A new formulation. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1997;44:515–525. doi: 10.1109/58.585136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasarathy S, Dasarathy J, Khiyami A, Joseph R, Lopez R, McCullough AJ. Validity of real-time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: A prospective study. J Hepatol. 2009;51:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida AM, Cotrim HP, Barbosa DB, de Athayde LG, Santos AS, Bitencourt AG, de Freitas LA, Rios A, Alves E. Fatty liver disease in severe obese patients: Diagnostic value of abdominal ultrasound. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1415–1418. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck FA. Physical Properties of Tissues. London: Academic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt V, Greenleaf GF. Ultrasound echo envelope analysis using a homodyned K distribution signal model. Ultrason Imaging. 1994;16:265–287. doi: 10.1177/016173469401600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei DY, Shung KK. Ultrasonic backscatter from mammalian tissues. J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;78:871–876. doi: 10.1121/1.393115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein MH, Gardner KG, Potter CJ, Schmalbrock P, Smith MA. Introduction of fast MR imaging in the assessment of hepatic steatosis. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(96)00224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane-Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitini D, Baruch Y, Ghersin E, Veitsman E, Kerner H, Shalem B, Yaniv G, Sarfaty C, Azhari H. Feasibility study of ultrasonic fatty liver biopsy: Texture vs. attenuation and backscatter. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:1321–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss SA, Johnston RL, Dunn F. Comprehensive compilation of empirical ultrasonic properties of mammalian tissue. J Acoust Soc Am. 1978;64:423–457. doi: 10.1121/1.382016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimond A, Teletin M, Garo E, D’Sa A, Selloum M, Champy MF, Vonesch JL, Monassier L. Quantitative ultrasonic tissue characterization as a new tool for continuous monitoring of chronic liver remodeling in mice. Liver Int. 2007;27:854–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MC, Lin JJ, Shu YC, Chen CN, Chang KJ, Chang CC, Tsui PH. Using ultrasound Nakagami imaging to assess liver fibrosis in rats. Ultrasonics. 2012;52:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyumpa AM, Jr, Greene HL, Dunn GD, Schenker S. Fatty liver: Biochemical and clinical consideration. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20:1142–1170. doi: 10.1007/BF01070758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska DP, Oelze ML. Improved parameter estimates based on the homodyned K distribution. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2009;56:2471–2481. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi Y, Ezuka H, Yamaguchi T, Hachiya H. Quantitative estimation method for liver fibrosis based on combination of Rayleigh distributions. Jap J Appl Phys. 2010;49:07HF06. (6 pages) [Google Scholar]

- Janiec DJ, Jacobson ER, Freeth A, Spaulding L, Blaszyk H. Histologic variation of grade and stage of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in liver biopsies. Obes Surg. 2005;154:497–501. doi: 10.1381/0960892053723268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainuma M, Fujimoto M, Sekiya N, Tsuneyama K, Cheng C, Takano Y, Terasawa K, Shimada Y. Cholesterol-fed rabbit as a unique model of nonalcoholic, nonobese, non-insulin-resistant fatty liver disease with characteristic fibrosis. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:971–980. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JL, Miller RJ, Blue JP, Jr, O’Brien WD, Jr, Erdman JW., Jr Inadequate dietary magnesium intake increases atherosclerotic plaque development in rabbits. Nutr Res. 2009;29:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavarello RJ, Ghoshal G, Oelze ML. On the estimation of backscatter coefficients using single-element focused transducers. J Acoust Soc Am. 2011;129:2903–2911. doi: 10.1121/1.3557036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T, Ophir J, Potter G. Correlation of ultrasonic attenuation with pathologic fat and fibrosis in liver disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1988;148:729–734. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(88)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizzi FL, Astor M, Liu T, Deng C, Coleman DJ, Silverman RH. Ultrasonic spectrum analysis for tissue assays and therapy evaluation. Int J Imag Syst Technol. 1997;8:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lu ZF, Zagzebski JA, Lee FT. Ultrasound backscatter and attenuation in human liver with diffuse disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1999;25:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu ZF, Zagzebski JA, O’Brien RT, Steinberg H. Ultrasound attenuation and backscatter in the livers during prednisone administration. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1997;23:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(96)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EL, Dong F, Frank GR, Gara BS, Wear KA, Wilson T, Zagzebski JA, Miller HL, Shung KK, Wang SH, Feleppa EJ, Liu T, O’Brien WD, Jr, Topp KA, Sanghvi NT, Zaitsen AV, Hall TJ, Fowlkes JB, Kripfgans OD, Miller JG. Interlaboratory comparison of ultrasonic backscatter, attenuation and speed measurements. J Ultrasound Med Biol. 1999;18:615–631. doi: 10.7863/jum.1999.18.9.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruvada S, Shung KK, Wang SH. High-frequency backscatter and attenuation measurements of selected bovine tissue between 10 and 30 MHz. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000;266:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SR, Thomas EL, Bell JD, Johnston DG, Taylor-Robinson SD. Noninvasive means of measuring hepatic fat content. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3476–3483. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman RB, Ferell LD, Patti MG, Weston SR, Pabst MS, Aouizerat BE, Bass NM. Correlation of paired liver biopsies in morbidly obese patients with suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2006;44:874–880. doi: 10.1002/hep.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P, Younossi ZM. Abdominal ultrasound for diagnosis of nonalcholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2716–2717. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien WD, Jr, Erdman JW, Jr, Hebner TB. Ultrasonic propagation properties (@100 MHz) in excessively fatty rat liver. J Acoust Soc Am. 1988;83:1159–1166. doi: 10.1121/1.396060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell M, Reilly HF., Jr Clinical evaluation of the B scan. IEEE Trans Sonics and Ultrasonics. 1985;SU32:450–457. [Google Scholar]

- Oelze M, Zachary JF, O’Brien WD., Jr Characterization of tissue microstructure using ultrasounic backscatter: Theory and technique for optimization using a Gaussian form factor. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:1202–1211. doi: 10.1121/1.1501278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, O’Brien WD, Jr, Zachary JF. Quantitative ultrasound assessment of breast cancer using a multiparameter approach. Proc 2007 IEEE Ultrason Sympos; 2007. pp. 981–984. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Fujii H, Yoshizato K, Kawada N. A human-type nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model with advanced fibrosis in rabbits. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:153–165. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K, Asztely M, Lerner R, Schenk E, Waag R. In vivo measurements of ultrasound attenuation in normal or diseased liver. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1988;14:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(88)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri P, Baillie RA, Wiest MM, Mirshahi F, Choudhury J, Cheung O, Sargeant C, Contos MJ, Sanyal AJ. A lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1081–1090. doi: 10.1002/hep.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, Gombert S, Giral P, Brucket E, Grimaldi A, Capron F, Poynard T. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1898–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon A, Alkhouri N, Carter-Kent C, Monti L, Devito R, Lopez R, Feldstein AE, Nobili V. Ultrasonographic quantitative estimation of hepatic steatosis in children with NAFLD. J Padiatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:190–195. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821b4b61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleefe GE, Lele PP. Tissue characterization based on scatterer number density estimation. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1988;35:749–757. doi: 10.1109/58.9332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Hayashi N, Sasaki Y, Kono M, Kasahara A, Fusamoto H, Imai Y, Kamada T. Dependence of ultrasonic attenuation of liver on pathologic fat and fibrosis: Examination with experimental fatty liver and liver fibrosis models. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1992;18:657–666. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(92)90116-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchelepi H, Ralls PW, Radin R, Grant E. Sonography of diffuse liver disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;21:1023–1032. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Techavipoo U, Varghese T, Chen Q, Stiles TA, Zagzebski JA, Frank GR. Temperature dependence of ultrasonic propagation speed and attenuation in excised canine liver tissue measured using transmitted and reflected pulses. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115:2859–2865. doi: 10.1121/1.1738453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui PH, Chang CC, Ho MC, Lee YH, Chen YS, Cheng CC, Huang NE, Wu ZH, Chang KJ. Use of Nakagami statistics and empirical mode decomposition for ultrasound tissue characterization by a nonfocused transducer. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:2055–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, Gara BS, Hall TJ. Measurements of ultrasonic backscatter coefficients in human liver and kidney in vivo. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;98:1852–1857. doi: 10.1121/1.413372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M, Yeshua H, Zelber-Sagi S, Santo E, Brazowski E, Halpern Z, Oren R. Diagnostic value of a computerized hepatorenal index for sonographic quantification of liver steatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:909–914. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieckowska A, Feldstein AE. Diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Invasive versus noninvasive. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:386–395. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LS, Robinson DE, Doust BD. Frequency domain processing for ultrasonic attenuation measurement in liver. Ultrason Imaging. 1984;6:278–292. doi: 10.1177/016173468400600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia MF, Yan HM, He WY, Li XM, Li CL, Yao XZ, Li RK, Zeng MS, Gao X. Standardized ultrasound hepatic/renal ratio and hepatic attenuation rate to quantify liver fat content: An improvement method. Obesity. 2011;20:444–452. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Hachiya H. Proposal of a parametric imaging method for quantitative diagnosis of liver fibrosis. J Med Ultrason. 2010;37:155–166. doi: 10.1007/s10396-010-0270-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiebel WJ. Sonographic diagnosis of diffuse liver disease. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:8–15. doi: 10.1016/0887-2171(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]