Abstract

DNA replication is regulated in response to environmental constraints such as nutrient availability. While much is known about regulation of replication during initiation, little is known about regulation of replication during elongation. In the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, replication elongation is paused upon sudden amino acid starvation by the starvation-inducible nucleotide (p)ppGpp. However, in many bacteria including Escherichia coli, replication elongation is thought to be unregulated by nutritional availability. Here we reveal that the replication elongation rate in E. coli is modestly but significantly reduced upon strong amino acid starvation. This reduction requires (p)ppGpp and is exacerbated in a gppA mutant with increased pppGpp levels. Importantly, high levels of (p)ppGpp, independent of amino acid starvation, are sufficient to inhibit replication elongation even in the absence of transcription. Finally, in both E. coli and B. subtilis, (p)ppGpp inhibits replication elongation in a dose-dependent manner rather than via a switch-like mechanism, although this inhibition is much stronger in B. subtilis. This supports a model where replication elongation rates are regulated by (p)ppGpp to allow rapid and tunable response to multiple abrupt stresses in evolutionarily diverse bacteria.

Introduction

Accurate and processive DNA replication is important for the maintenance of genome integrity. The intricate coordination of multiple components of the replisome, including the replicative helicase that unwinds the double stranded DNA to expose the single stranded template, DNA polymerases that synthesize daughter strands, the primase that synthesizes the RNA primer, and auxiliary components such as the beta clamp, the clamp loader and the single stranded DNA binding protein (McHenry, 2003; Pomerantz and O'Donnell, 2007), is important for the fidelity and efficiency of DNA replication.

Replication is tightly regulated to be coordinated with growth and responsive to external cues such as nutrient availability (Katayama, 2001). In E. coli, replication initiation is inhibited by amino acid starvation via reduced translational capacity to synthesize the initiation protein DnaA (Hill et al., 2012) and via the starvation-inducible nucleotides guanosine pentaphosphate (pppGpp) and guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), collectively known as (p)ppGpp (Potrykus and Cashel, 2008; Schreiber et al., 1995; Ferullo and Lovett, 2008). This allows a cell to initiate replication only in the presence of sufficient nutrients, preventing over-replication and maintaining the correct number of chromosomes per cell (Donachie, 1968), an important aspect of genome integrity.

Of the three phases of replication- initiation, elongation and termination, the period of replication elongation is the longest. During the elongation phase, environments can change, deleteriously affecting replication. However, in E. coli replication forks were thought to proceed unregulated beyond the single origin of replication, oriC, regardless of changes in nutrient availability, until terminated or disrupted (Zakrzewska-Czerwinska et al., 2007). In contrast to E. coli, a putative regulatory response of replication elongation was observed in the Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis. Replication forks are non-disruptively arrested upon amino acid starvation throughout the elongation phase, thus pausing replication in anticipation of problems that may disrupt faithful replication. This response requires the accumulation of (p)ppGpp, although it is unclear whether (p)ppGpp is sufficient for this response in the absence of starvation. (p)ppGpp directly inhibits B. subtilis primase activity in vitro, which is proposed to underlie the observed replication arrest in B. subtilis (Wang et al., 2007).

Paradoxically, E. coli primase activity is also directly inhibited by (p)ppGpp in vitro (Maciag et al., 2010; Rymer et al., 2012), although decades of classical and modern experiments have not revealed any inhibitory effect of amino acid starvation on E. coli replication elongation (Lark and Lark, 1966; Billen and Hewitt, 1966; Marsh and Hepburn, 1980; Levine et al., 1991; Ferullo and Lovett, 2008; Tehranchi et al., 2010). This disparity between in vitro and in vivo results suggests that either (p)ppGpp also inhibits replication elongation in E. coli, as recently hypothesized (Maciag et al., 2010), or that replication elongation control by (p)ppGpp is not mediated by primase.

To resolve this apparent contradiction and to examine whether regulation of elongation is unique to B. subtilis or is conserved in divergent bacteria, we quantified genome-wide replication fork progression in E. coli cells and discovered that acute amino acid starvation not only inhibited replication initiation, but also modestly reduced the rate of replication elongation. We found that (p)ppGpp was both necessary and sufficient to inhibit replication elongation independently of its effect on transcription. We further observed that (p)ppGpp inhibited replication elongation quantitatively in both E. coli and B. subtilis, with higher concentrations of (p)ppGpp inhibiting replication elongation more strongly. This modulation may be the manifestation of a conserved regulatory mechanism in bacteria to maintain genome integrity.

Results

Amino Acid Starvation Results in a (p)ppGpp-Dependent Reduction of Replication Elongation Rate in E. coli

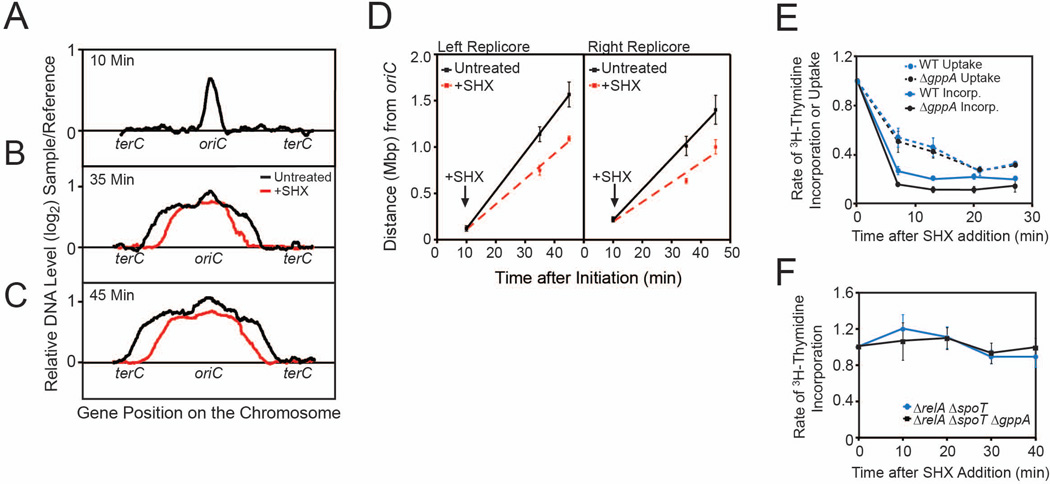

We investigated whether replication elongation is affected by amino acid starvation in living E. coli cells. We monitored replication fork progression in a synchronized population of E. coli cells using genomic microarrays (Khodursky et al., 2000; Tehranchi et al., 2010). Cells carrying a temperature sensitive (dnaC2) mutant of the helicase loader DnaC (Carl, 1970) were grown in minimal medium; replication was synchronized by shifting the culture to 42°C to inhibit replication initiation while allowing the current round of replication to complete, and then returned to 30°C to allow synchronized release of a new round of replication (Figure 1A). Serine hydroxamate (SHX), which mimics amino acid starvation and induces (p)ppGpp to high levels (Pizer and Merlie, 1973), was added 10 minutes after temperature downshift and the gene dosage profiles at 10 minutes (Figure 1B), 35 minutes (Figure 1C) and 45 minutes (Figure 1D) after temperature downshift were obtained. Replication fork positions were calculated as the midpoint of gene dosage between replicated and unreplicated regions (Figure 1E). The rates of replication elongation, calculated by linear regression of replication fork positions at 10, 35 and 45 minutes (Table 1), were found to be reduced by 13±2% upon starvation, illuminating a modest but significant (p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test), previously unknown effect of amino acid starvation on the replication elongation rate in E. coli.

Figure 1. Amino Acid Starvation Reduces Replication Elongation Rates in E. coli.

(A) Schematic of the experimental strategy for monitoring replication elongation upon amino acid starvation using whole-genome microarrays. E. coli dnaC2 cells were grown in M9 medium at 30°C to log phase and synchronized by shifting to 42°C to inhibit replication initiation. Replication initiation was allowed to start by temperature shift back to 30°C. Cultures were treated with SHX (0.5 mg/ml) 10 minutes after initiation of replication and collected at 35 and 45 minutes after initiation. (B–D) Overlay of microarray profiles of starved (red) and untreated (black) synchronized dnaC2 cells sampled 10 (B), 35 (C) and 45 (D) minutes after initiation. Each panel is obtained from a single experiment and is representative of two independent biological replicates. (E) Average distance of replication forks from oriC as a function of time after initiation for untreated (solid lines) and SHX-treated (dotted lines) cultures, obtained from microarray profiles. Error bars indicate ranges (from 2 independent biological replicates). Straight lines: linear regression of fork positions at 10, 35 and 45 minutes after initiation. (F) DNA replication in dnaC2 ΔrelA cells was monitored by DNA microarrays as in (A). Shown is the overlay of microarray profiles of SHX-treated (red) and untreated (black) synchronized dnaC2 ΔrelA cells sampled 35 minutes after initiation.

Table 1. Effects of (p)ppGpp Induction on the Rates of Replication Elongation in E. coli.

Synchronized cells were treated with SHX (0.5 mg/ml) or IPTG (1 mM) to induce expression of a constitutive allele of RelA (RelA*). Average replication fork positions were calculated as the midpoints between replicated and unreplicated regions. Replication rates were calculated by linear regression of a time course of microarrays.

| Strain | Treatment | Elongation Rate (bp/s)a |

% Reduction of Elongation Ratea,b |

|---|---|---|---|

| dnaC2 | Untreated | 651±23 | |

| SHX | 565±27 | 13±2% | |

| dnaC2 ΔgppA | Untreated | 621±14 | |

| SHX | 403±21 | 35±3% | |

| dnaC2 mal::lacIq pRelA* | Untreated | 592±12 | |

| IPTG | 503±24 | 15±4% | |

| dnaC2 mal::lacIq ΔgppA pRelA* | Untreated | 604±17 | |

| IPTG | 386±12 | 36±3% |

±Range

Treated/untreated

Inhibition of replication elongation in wild-type cells may be due to amino acid starvation alone or due to the accumulation of (p)ppGpp upon starvation. To determine whether (p)ppGpp induction is necessary for this inhibition, we examined cells lacking the (p)ppGpp synthetase RelA that is responsible for production of (p)ppGpp in response to amino acid starvation (Potrykus and Cashel, 2008). Replication fork progression was no longer affected by starvation in dnaC2 ΔrelA cells (Figure 1F), indicating that inhibition of replication elongation requires (p)ppGpp induction in E. coli.

Deletion of gppA Further Slows Replication Elongation During Starvation

As (p)ppGpp induction upon starvation in E. coli cells results in a modest reduction of replication elongation rate, we examined whether further increasing (p)ppGpp concentration inhibits replication elongation more strongly. This can be achieved by deleting gppA, which encodes a phosphatase that converts pppGpp to ppGpp in E. coli (Somerville and Ahmed, 1979) (Figure 2A). Using Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC), we confirmed that, in dnaC2 ΔgppA cells, ppGpp was induced by SHX to similar levels as in wild-type cells, but pppGpp levels were ~2 fold higher (Figure 2B–D; Table S1). Levels of GTP, a precursor of pppGpp and a substrate for primase, were reduced similarly in the presence or absence of GppA (Figure 2E; Table S1).

Figure 2. Deletion of gppA Results in Higher pppGpp Levels upon Amino Acid Starvation in E. coli.

(A) Schematic representation of (p)ppGpp metabolism in E. coli highlighting the role of GppA in production of ppGpp from pppGpp. (B–E) Measurement of nucleotide levels in dnaC2 and dnaC2 ΔgppA cells. Nucleotides were extracted from 32P-labeled cells treated with SHX (0.5 mg/ml) and analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) as shown in (B). (p)ppGpp, GTP and ATP levels were quantified in ImageQuant and normalized by the number of phosphates in each nucleotide. (p)ppGpp levels are displayed as the molar ratios to GTP (C) or ATP (D). GTP levels are displayed as the molar ratios to ATP (E).

We monitored synchronized replication fork progression in these cells and found stronger inhibition of replication elongation during starvation in the absence of gppA (Figure 3A–D). While replication elongation rates were not significantly reduced by gppA deletion in untreated cells, upon starvation elongation rates were reduced by 35±3% (p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test), a 2–3 fold further reduction compared with starved dnaC2 cells (13±2%).

Figure 3. Replication Elongation Rates are More Strongly Reduced in Amino Acid-Starved ΔgppA E. coli Cells.

(A–C) Overlay of microarray profiles of treated (red) and untreated (black) synchronized dnaC2 ΔgppA cells sampled 10 (A), 35 (B) and 45 (C) minutes after initiation. Each panel shows data from a single experiment and is representative of two independent experiments. (D) Average distance of replication forks from oriC as a function of time after initiation for untreated (solid lines) and SHX-treated (dotted lines) cultures, obtained from microarray profiles. Straight lines: linear regression of fork positions at 10, 35 and 45 minutes after initiation. Error bars indicate ranges (from 2 independent biological replicates). (E) DNA replication rates in asynchronous cells in a time course following SHX treatment. Cells were pulse-labeled with 3H-thymidine, the rates of 3H-thymidine incorporation into DNA (solid lines) or uptake into cells (dotted lines) upon SHX treatment are normalized to untreated samples. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (from 3–5 independent replicates). (F) DNA replication in cells lacking both relA and spoT measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation as described in (E). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (from 3–5 independent replicates).

To rule out the possibility that this reduction stems from a synthetic effect between the gppA deletion and the dnaC2 allele, we measured replication rates in ΔgppA cells with wild-type dnaC by monitoring the incorporation of 3H-thymidine into DNA. While inhibition of replication initiation results in a gradual decrease of 3H-thymidine incorporation over the course of a replication cycle, inhibition of elongation results in a rapid decrease of 3H-thymidine incorporation. We observed a rapid decrease in the rate of 3H-thymidine incorporation during amino acid starvation in wild-type cells and found that gppA deletion resulted in a significant further reduction (Figure 3E). It has been shown that (p)ppGpp induction also decreased the uptake of thymidine (Lin-Chao and Bremer, 1986), which contributed to the decrease in 3H-thymidine incorporation. However, deletion of gppA did not further decrease thymidine uptake (Figure 3E), suggesting that the difference in thymidine incorporation we observed in SHX-treated ΔgppA cells was due to reduction of DNA replication elongation rates in the presence of wild-type dnaC.

GppA not only converts pppGpp to ppGpp, but also has an exopolyphosphatase activity (Keasling et al., 1993). We ruled out this (p)ppGpp-independent role of GppA on replication elongation by examining the effect of gppA deletion in cells devoid of any (p)ppGpp, via removal of both (p)ppGpp synthetases: RelA and SpoT. There was no appreciable reduction of the replication rate in ΔrelA ΔspoT ΔgppA cells upon SHX treatment (Figure 3F), confirming that the inhibition of replication elongation in the ΔgppA mutant resulted from increased pppGpp levels.

(p)ppGpp is Sufficient to Slow Replication Elongation in E. coli

In E. coli (Figure 1–3) and B. subtilis (Wang et al., 2007), the inhibitory effects of (p)ppGpp on replication elongation were revealed only under amino acid starvation. Therefore, we sought to determine whether (p)ppGpp induction alone, not in combination with amino acid starvation, was sufficient to reduce replication elongation rates in E. coli. We used a plasmid (pRelA*, also called pSM11) that allows IPTG-induction of a truncated form of RelA (RelA*), which produces (p)ppGpp constitutively even in the absence of amino acid starvation (Schreiber et al., 1991). Upon induction, RelA* produced high levels of (p)ppGpp, and pppGpp levels were further elevated by gppA deletion (Figure 4A–C; Table S1). RelA* induction reduced GTP levels to the same extent regardless of gppA deletion (Figure 4D; Table S1).

Figure 4. RelA* Produces High Levels of (p)ppGpp in the Absence of Amino Acid Starvation in E. coli.

(A) Measurement of nucleotide levels in dnaC2 pRelA* and dnaC2 ΔgppA pRelA*cells. Cells were grown in MOPS low phosphate medium supplemented with casamino acids, 32P-labeled, and treated with 1 mM IPTG to induce expression of RelA* for 45 minutes. Nucleotides were extracted and separated by TLC. (B, C) (p)ppGpp levels at indicated times after induction of RelA*. Nucleotide levels were quantified and normalized as described in Figure 2. Error bars indicate standard deviation of 3 independent replicates. (D) GTP levels after induction of RelA* were quantified and normalized as described in Figure 2. Error bars indicate standard deviation of 3 independent replicates.

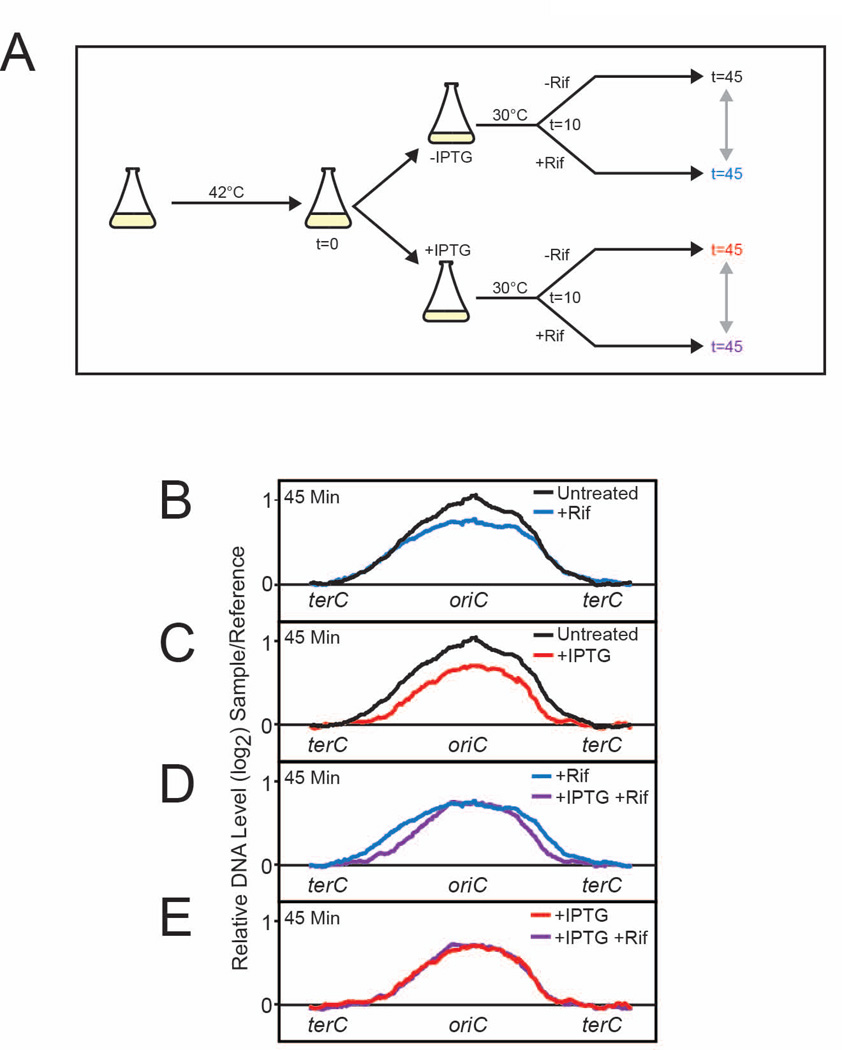

Next, we released replication forks from oriC in a synchronized population of pRelA* dnaC2 cells by temperature downshift and concurrently added IPTG to induce RelA*, thus allowing (p)ppGpp to accumulate after replication initiation but achieving maximum levels before the existing round of replication forks reached the terminus (Figure 5A). We verified 10 minutes after temperature downshift that the gene dosage at oriC doubled, indicating there was effective replication initiation (Figure 5B, C). We also verified 45 minutes after temperature downshift that a fraction of untreated cells initiated a second round of replication, as gene dosage at oriC increased greater than two-fold (Figure 5D, E). Expectedly, this re-initiation was not observed in RelA*-induced cells, as (p)ppGpp is known to inhibit replication initiation (Ferullo and Lovett, 2008; Schreiber et al., 1995). Notably, we also observed a clear inhibitory effect of RelA* production on replication elongation by 15±4% in the presence of gppA (Figure 5D, F, Table 1) and by 36±3% in the absence of gppA (Figure 5E, G, Table 1). These results indicate that induction of (p)ppGpp is sufficient to slow replication fork progression even without starvation in E. coli.

Figure 5. High Levels of (p)ppGpp are Sufficient to Inhibit Replication Elongation in E. coli.

(A) Schematic of the experimental strategy for monitoring the effect of RelA* induction on replication elongation. Cells were grown to mid-log phase at 30°C, synchronized by shifting to 42°C for 90 minutes and back to 30°C. IPTG (1 mM) was added immediately after temperature downshift and replication was monitored at 10 and 45 minutes after temperature downshift. (B–E) Representative microarray replication profiles of dnaC2 pRelA* cells (B, D) and dnaC2 ΔgppA pRelA* cells (C, E) in M9 minimal medium. Shown is the overlay of microarray profiles of IPTG-treated (red) and untreated (black) cells 10 minutes (B, C) and 45 minutes (D, E) after temperature downshift. Dashed grey lines indicate 2-fold increase of gene dosage. (F–G) Average distance of replication forks from oriC as a function of time after initiation for untreated (solid lines) and SHX-treated (dotted lines) cultures, obtained from microarray profiles of dnaC2 pRelA* (F) and dnaC2 ΔgppA pRelA* cells (G). Error bars indicate the range from 2 independent replicates. Similar results were obtained for cells grown in casamino acids (data not shown).

Inhibition of Replication Elongation by (p)ppGpp in E. coli is Independent of its Effect on Transcription

(p)ppGpp is a global regulator of transcription and has been shown to negatively regulate many genes, including genes involved in nucleotide biosynthesis and components of the replisome (Durfee et al., 2007). To rule out the possibility that the reduced replication elongation rates are due to reduced expression of replication-related factors by (p)ppGpp, we treated cells with rifampicin, an inhibitor of transcription initiation, and examined synchronized replication fork progression with and without induction of (p)ppGpp (Figure 6A). Rifampicin treatment alone inhibited replication initiation but did not inhibit replication elongation (Figure 6B), suggesting that inhibiting the transcription of replication-related factors does not slow replication fork progression. Next, we examined the effect of (p)ppGpp on replication fork progression in the presence of rifampicin. We induced (p)ppGpp using the pRelA* system, as RelA*, once expressed, should continue synthesizing (p)ppGpp even after the addition of rifampicin. Consistent with prior results, induction of RelA* inhibited both initiation and elongation of replication (Figure 6C). Importantly, the presence of rifampicin, added 10 minutes after initiation of replication, did not affect the ability of RelA* to reduce replication elongation rates (Figure 6D). In fact, (p)ppGpp slowed replication fork progression to the same extent regardless of the presence of rifampicin (Figure 6E). These results indicate that (p)ppGpp reduces the rates of replication elongation independently of its effect on transcription.

Figure 6. High levels of (p)ppGpp in the Absence of Transcription Inhibit Replication Elongation in E. coli.

(A) Schematic of the experimental strategy for monitoring the effect of RelA* induction and rifampicin on replication elongation. dnaC2 ΔgppA pRelA* cells were grown in M9 medium supplemented with casamino acids to mid-log phase, synchronized by shifting to 42°C for 90 minutes and back to 30°C to initiate replication. IPTG (1 mM) was added immediately after temperature downshift to induce relA*. After 10 minutes, cells were treated with 0.3 mg/ml rifampicin, and sampled for microarrays profiling 45 minutes after temperature downshift. (B–E) Overlays of microarray profiles of untreated (black) and rifampicin-treated (blue) cells (B), untreated and IPTG-treated (red) cells (C), rifampicin-treated and IPTG+rifampicin-treated (purple) cells (D), and IPTG-treated and rifampicin+IPTG treated cells (E).

Inhibition of Replication Elongation by (p)ppGpp is Dose-Dependent in both E. coli and B. subtilis

Our observation of a stronger reduction of replication elongation rates in a gppA mutant with higher pppGpp led us to propose a quantitative relationship between (p)ppGpp levels and replication elongation rates in E. coli. Although we cannot clearly distinguish whether higher total (p)ppGpp levels or higher pppGpp levels account for the increased inhibition of elongation in ΔgppA cells, previous in vitro results show that both pppGpp and ppGpp inhibit E. coli primase activity with IC50 at low mM range (Maciag et al., 2010; Rymer et al., 2012), similar to the estimated (p)ppGpp levels under strong starvation conditions. We next correlated total (p)ppGpp levels (normalized to GTP or ATP in molar ratios) (Figure 7A,B) or ppGpp and pppGpp levels individually (Figure S1) with replication elongation rates obtained by microarrays. We found that elongation rates were inversely correlated with both (p)ppGpp/GTP and (p)ppGpp/ATP ratios (Pearson’s correlation, r = −0.86, p<0.01 and r = −0.93, p<0.001 respectively). These results suggest that (p)ppGpp-mediated inhibition of elongation is dose-dependent in E. coli.

Figure 7. Inhibition of Replication Elongation by (p)ppGpp is Dose-Dependent in both E. coli and B. subtilis.

(A–B) Replication elongation rates in E. coli cells were plotted against total (p)ppGpp levels presented as the molar ratio to GTP (A) or ATP (B) under different conditions: dnaC2 and dnaC2 ΔgppA cells treated with 0.5 mg/ml SHX, and dnaC2 pRelA* and dnaC2 ΔgppA pRelA* cells treated with 1 mM IPTG (Table 1). Data were fit by linear regression. r: Pearson’s correlation coefficient. (C) Levels of pppGpp and ppGpp in B. subtilis cells measured under multiple stress conditions. 32P-labeled cells with or without expression of E. coli gppA from an IPTG-inducible promoter (Phyperspank-gppA) were treated with 0.5 mg/ml norvaline (Norv), 2% α-methyl-glucoside (α-MG) or 0.5 mg/ml RHX for 10 minutes. Nucleotides were extracted, separated by TLC and quantified as in Figure 2. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean from 3–6 replicates. (D) DNA replication rates of B. subtilis cells under the conditions described in (C) were measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation and normalized to t=0. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean from 3 replicates. (E–F) Replication rates under above conditions were plotted against total (p)ppGpp levels presented as the molar ratio to GTP (E) or ATP (F) in B. subtilis. Data were fit to y=100/(1+(x/IC50)) where y is the replication rate, and x is the relative (p)ppGpp level. r: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Finally, we tested whether (p)ppGpp-mediated inhibition of elongation is also dose-dependent in B. subtilis where we have previously observed replication arrest upon strong starvation conditions (Wang et al., 2007). In an attempt to alter (p)ppGpp levels, we over-expressed E. coli gppA in B. subtilis by using an IPTG-inducible promoter. We combined this variation with several treatments: norvaline (Belitskii and Shakulov, 1980), α-methyl glucoside (Hansen et al., 1975) and arginine hydroxamate (RHX), to obtain varying (p)ppGpp levels (Figure 7C; Table S2) and examined their effects on replication rates (Figure 7D; Table S2). We identified a strong correlation between total (p)ppGpp levels relative to either GTP (Figure 7E) or ATP (Figure 7F) and rates of DNA replication (Spearman’s rank correlation, r = −0.95, p<0.001 and r = −0.93, p<0.001 respectively), indicating that, similar to the situation in E. coli, inhibition of replication elongation by (p)ppGpp in B. subtilis is dose-responsive. Replication elongation rates were inhibited by 50% at a (p)ppGpp/GTP ratio of 0.32 (Figure 7E) and a (p)ppGpp/ATP ratio of 0.035 (Figure 7F); the potency of the inhibition was much higher than observed for E. coli (Figure 7A).

Discussion

DNA replication is tightly regulated by amino acid availability during initiation in E. coli (Chiaramello and Zyskind, 1990; Schreiber et al., 1995; Ferullo and Lovett, 2008). Here we measured replication elongation rates directly with a genomic approach, revealing an additional inhibitory effect of amino acid starvation on replication elongation in living E. coli cells. (p)ppGpp, which accumulates in response to multiple stress conditions including amino acid starvation, is responsible and sufficient for this inhibition. (p)ppGpp modulated elongation in both E. coli and B. subtilis quantitatively, although much stronger in B. subtilis. Our results support a model in which evolutionarily divergent bacteria exert rapid and tunable control of replication elongation in response to stress conditions, which could contribute to preservation of genome integrity.

Direct or Indirect: Modulation of Replication Elongation Rates by (p)ppGpp in E. coli

Replication elongation in E. coli can be inadvertently inhibited by factors including DNA topology (Khodursky et al., 2000) and protein roadblocks to DNA replication (Possoz et al., 2006). The inhibitory effect of (p)ppGpp we observed on elongation could be due to these indirect effects rather than by a direct and active regulatory mechanism. For example, amino acid starvation may lead to a failure to synthesize proteins required for DNA replication and/or to a creation of transcription–replication conflicts, resulting in the apparent slow down of replication forks. However, this possibility is largely ruled out because accumulation of (p)ppGpp is sufficient to inhibit replication elongation in the absence of starvation (Figure 5).

Several roles of (p)ppGpp may indirectly affect replication fork progression. It is possible that the replication elongation effect we observed was due to the effect of (p)ppGpp on transcription initiation (Barker et al., 2001). However, by addition of rifampicin we showed that reduction of replication elongation rates did not result from effects of (p)ppGpp on gene expression (Figure 6). Further, (p)ppGpp was previously shown to lower the stability of transcription elongation complexes in E. coli, removing RNA polymerase arrays accumulated at damaged DNA templates (Trautinger et al., 2005). However, (p)ppGpp, via this mechanism, would remove potential roadblocks to replication and thus maintain replication fork progression during amino acid starvation, an effect opposite to what we observed. Finally, it remains a formal possibility that dNTP levels are depleted by (p)ppGpp, accounting for the reduction of replication elongation. However, this is unlikely, as depleting dNTP would elicit disruptive replication arrest. Instead, by modulating replication elongation directly, (p)ppGpp may prevent replication under depleted dNTP pools, thus protecting integrity of the replication forks.

While we cannot rule out all indirect effects, given the in vitro results that both E. coli and B. subtilis primase activities are inhibited by (p)ppGpp (Rymer et al., 2012) and prior in vivo evidence from B. subtilis (Wang et al., 2007), (p)ppGpp likely mediates active elongation control in both bacteria via its direct effects on primase. To demonstrate that (p)ppGpp reduces replication elongation rates by targeting primase activity might require the identification of a primase mutant that is refractory to (p)ppGpp inhibition while retaining its priming activity, which requires future work. This mutant would be valuable for dissecting replication control and for understanding the function of (p)ppGpp in general.

Beyond a Switch: Modulating the Rate of Replication Fork Progression by (p)ppGpp

Previously in B. subtilis, replication forks were observed to arrest during amino acid starvation (Copeland, 1971; Wang et al., 2007; Levine et al., 1991). This, together with the general view that E. coli lacks elongation control, implied there is a major difference between the two organisms in how they control replication in response to sudden stress. Our results suggest that (p)ppGpp modulates replication elongation in both B. subtilis and E. coli by a dose-dependent and possibly conserved mechanism, although the inhibition is much stronger in B. subtilis. Severe inhibition of replication elongation in B. subtilis was experimentally indistinguishable from arrest (Wang et al., 2007).

What accounts for the far more potent inhibition of replication elongation by (p)ppGpp observed in B. subtilis is an open question. The possibility that B. subtilis primase is more sensitive to (p)ppGpp than E. coli primase has been largely ruled out in vitro (Maciag et al., 2010; Rymer et al., 2012). Primase activity, which is known to affect replication fork progression (Wu et al., 1992a; Wu et al., 1992b; Zechner et al., 1992; Lee et al., 2006), could be more restrictive to fork progression in B. subtilis. There is a difference between the replisome components in the two species. In B. subtilis, lagging strand synthesis requires an additional DNA polymerase, DnaE. After primase creates the RNA primer, DnaE elongates the primer to synthesize a short stretch of DNA before handing-off to the processive replicative DNA polymerase PolC (Sanders et al., 2010).

A factor likely contributing to the more potent inhibition of replication elongation by (p)ppGpp is the low concentration of GTP in B. subtilis during (p)ppGpp-induction due to direct and potent inhibition of GTP biosynthesis by (p)ppGpp (Kriel et al., 2012; Gallant et al., 1971; Lopez et al., 1981). As (p)ppGpp binds to primase at partially overlapping sites with NTPs and inhibits primase activity in a GTP-concentration dependent manner (Rymer et al., 2012), a further reduction of GTP levels in combination with induction of (p)ppGpp may lead to stronger inhibition of replication elongation in B. subtilis than in E. coli. Finally, in B. subtilis, it is conceivable that (p)ppGpp inhibits targets in addition to primase, resulting in stronger inhibition of replication elongation than in E. coli. Future experiments will be needed to reveal the basis for the quantitative differences in inhibition of replication between these bacteria, even though the basic mechanism appears to be conserved.

Modulation of Replication Elongation: A Possible Means to Protect Genome Integrity under Multiple Stress Conditions

Inhibition of replication elongation by (p)ppGpp in E. coli is modest and observed only under sudden stress conditions. It is possible that this response is restricted to acute stress conditions and has only minor physiological impact. However, it seems also likely that this is a true regulatory mechanism with a broader impact than the modest reduction in elongation rate might suggest. The observed inhibition of replication elongation is genome-wide and averaged over the entire population of cells, implying that the replication fork is either slowed at every position of the genome or strongly affected at particular locations of the genome (e.g., priming sites). If the latter, the inhibitory impact at those sites may be more dramatic than suggested by the overall measurement. Furthermore, a small reduction of the rate of replication may increase the opportunity for quality control mechanisms to protect replication forks, even under less severe stress conditions where the reduction of the rate of replication fork progression is less than the observed 13%.

While regulation of replication initiation, the major regulatory step of DNA replication in E. coli, is crucial for maintaining the correct chromosome number and sometimes can prevent replication fork collapse (Simmons et al., 2004), regulation of elongation may maintain genome integrity in aspects that cannot be controlled at initiation, such as replication fidelity at single nucleotide levels. (p)ppGpp has the advantage of an immediate response, constantly coupling the status of replication elongation with the cellular milieu. The existence of mechanisms specific for severe starvation conditions is not limited to the effect of (p)ppGpp on replication elongation: for example, the trp attenuation system is needed for regulation of gene expression during extreme tryptophan starvation despite the fact that Trp Repressor is sufficient to regulate expression under modest starvation conditions.

Because (p)ppGpp accumulates under a wide variety of conditions, such as starvation for phosphate (Spira et al., 1995), lipids (Battesti and Bouveret, 2006), carbon (Winslow, 1971; Lazzarini et al., 1971) and iron (Vinella et al., 2005), as well as under heat stress (VanBogelen and Neidhardt, 1990) and acid stress (Kanjee et al., 2011), it may broadly modulate replication elongation. Moreover, the severity of the stress is coupled to the reduction in replication progression rate; i.e. it is dose-dependent. This suggests there is a trade-off between growth and genome integrity, providing cells with a tunable response to stress and modulate replication elongation accordingly, thus optimizing the efficiency, fidelity, and adaptability of genome duplication.

Experimental Procedures

Strains and Growth Conditions

All E. coli strains used are derivatives of MG1655 (Blattner et al., 1997) or W3110 (Hayashi et al., 2006) as listed in Table 2. Standard growth, transformation, and transduction protocols were used (Miller, 1992). Deletion strains were constructed by phage transduction from the Keio collection (Baba et al., 2006). E. coli cells were grown with shaking at 30°C or 37°C in M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, with or without 0.4% casamino acids or 40 µg/ml threonine. For measurement of nucleotide levels, cells were grown in MOPS medium with phosphate reduced from 1.32 mM to 1 mM.

Table 2. Strains and Plasmids.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 | F− λ− ilvG− rfb-50 rph-1, sequenced wild-type K12 | (Blattner et al., 1997) |

| JDW402 | MG1655 ΔgppA::FRT-kan-FRT | This work |

| NC2943 | W3110 F- dnaC2(Ts) thr::Tn10 | (Carl, 1970) |

| JDW518 | W3110 F- dnaC2(Ts) thr::Tn10 ΔgppA::FRT-kan-FRT | This work |

| JDW519 | W3110 F- dnaC2(Ts) thr::Tn10 ΔrelA::kan | (Tehranchi et al., 2010) |

| CH1059 | MG1655 rph+ lacIpoZΔ(Mlu) ΔrelA256::FRT ΔspoT212::FRT | Michael Cashel |

| JDW1428 | MG1655 rph+ lacIpoZΔ(Mlu) ΔrelA256::FRT ΔspoT212::FRT ΔgppA::FRT-kan-FRT | This work |

| JDW1501 | MG1655 F- ΔlacX74 mal::lacIq dnaC2(Ts) thr::Tn10 pSM11 | This work |

| JDW1502 | MG1655 F- ΔlacX74 mal::lacIq dnaC2(Ts) thr::Tn10 ΔgppA::FRT-kan-FRT pSM11 | This work |

| JDW1775 | SMY amyE::Phyperspank | This work |

| JDW1776 | SMY amyE::Phyperspank-gppA | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSM11 (pRelA*) | Contains 455 codons from the E. coli relA gene placed under the control of the tac promoter | (Schreiber et al., 1995) |

| pDR111 | Phyperspank | David Rudner |

| pJW125 | Phyperspank-gppA | This work |

All B. subtilis strains used were derivatives of SMY (Schaeffer et al., 1965) as listed in Table 2. Standard growth and transformation procedures were used unless otherwise indicated (Vasantha and Freese, 1980). B. subtilis cells were grown in defined S7 medium (Vasantha and Freese, 1980) with MOPS buffer at 50 mM rather than 100 mM and supplemented with 0.1% glutamate, 1% glucose and 0.4% casamino acids. For measurement of nucleotide levels, phosphate was reduced from 5 mM to 0.5 mM.

To introduce GppA to B. subtilis, E. coli gppA was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using the following primers:

oJW104: 5’-CCCGTCGACTCATAAAGGAGGAACTACAATGGGTTCCACCTCGTCGC

oJW105: 5’- CCCGCATGCATCGCATCCGGCACTTACTC

The resulting PCR product was inserted into the SalI and SphI sites of pDR111 to place gppA under an IPTG inducible promoter to obtain plasmid pJW125. pJW125 was transformed into B. subtilis cells by selecting for resistance to spectinomycin to replace amyE with IPTG-inducible gppA to obtain JDW1776.

Thin Layer Chromatography

Previously published protocols (Schneider et al., 2003) were used for E. coli and B. subtilis cells. Cells were labeled with 20 µCi/ml (E. coli) or 30 µCi/ml (B. subtilis) 32P orthophosphate (900 mCi/mmol, Perkin-Elmer) for 4–5 generations. Nucleotides were extracted in 1 M formic acid and loaded on PEI cellulose plates (JT. Baker). Plates were developed in 1.5 M KH2PO4 (pH 3.4), exposed onto a Storage Phosphor Screen, and scanned using a GE Typhoon Scanner. Spots were quantified using ImageQuant software. All nucleotides were normalized by phosphate number and expressed as molar ratios to GTP and ATP.

Thymidine Incorporation and Uptake Assays

Cells were grown at 37°C to mid-log phase, treated, and labeled by mixing 5 µl of 3H-thymidine (80 Ci/mmol, 1 mCi/ml, Perkin Elmer) with 200 µl of culture for 2 minutes. To measure DNA synthesis (incorporation of 3H label into nucleic acid), ice-cold TCA (final concentration of 10%) was mixed with labeled samples and incubated on ice for 30 min. Samples were filtered and washed with ice-cold 5% TCA on GF-A filters (Whatman). To measure uptake of 3H label into cells, samples (not treated with TCA) were filtered onto 0.45 µM membrane filters (Pall Life Sciences) and washed with 0.1 M LiCl. The amount of radioactivity remaining on the filter was measured by scintillation counting (Beckman LS500 TD).

Monitor Replication Elongation with Genomic Microarrays

Replication was synchronized using the dnaC2 temperature sensitive allele (Carl, 1970). Cells were grown at the permissive temperature (30°C) to OD600 ~0.2, shifted to the non-permissive temperature (42°C) for 90 minutes, then shifted back to 30°C to allow a new round of replication to initiate. Cells were collected and genomic DNA was purified as described (Breier et al., 2005). DNA samples were labeled with Cy3 (stationary phase reference) and Cy5 (sample) and hybridized to Agilent oligo-arrays following the Agilent oligo-aCGH protocol, as described previously (Tehranchi et al., 2010).

Analysis was performed using the Agilent Feature Extraction software. A ratio of the fluorescence intensity of sample versus stationary phase reference DNA was obtained as the median of ~10 probes designed for each gene. The resulting ratios were plotted against the gene positions along the chromosome and smoothed by moving median with a window size of 100–150 genes to obtain gene dosage profiles. The average position of the replication forks relative to oriC was obtained as the midpoint between replicated and unreplicated regions of the first round of replication. Linear regression analysis of fork positions over time was used to calculate the rate of replication elongation. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests (Wilcoxon, 1945; Mann and Whitney, 1947) were performed to assign significance of difference of replication rates between treated and untreated samples using the Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Christophe Herman, James Berger and Michael Cashel for reagents, Richard Gourse, Susan Rosenberg, members of the Wang lab and the anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH R01GM084003 and Welch Foundation research grant to JDW.

References

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. 2006 0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker MM, Gaal T, Josaitis CA, Gourse RL. Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:673–688. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battesti A, Bouveret E. Acyl carrier protein/SpoT interaction, the switch linking SpoT-dependent stress response to fatty acid metabolism. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1048–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belitskii BR, Shakulov RS. Guanosine polyphosphate concentration and stable RNA synthesis in Bacillus subtilis following suppression of protein synthesis. Mol Biol (Mosk) 1980;14:1342–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billen D, Hewitt R. Influence of starvation for methionine and other amino acids on subsequent bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid replication. J Bacteriol. 1966;92:609–617. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.3.609-617.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G, 3rd, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier AM, Weier HU, Cozzarelli NR. Independence of replisomes in Escherichia coli chromosomal replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3942–3947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500812102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl PL. Escherichia coli mutants with temperature-sensitive synthesis of DNA. Mol Gen Genet. 1970;109:107–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00269647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaramello AE, Zyskind JW. Coupling of DNA replication to growth rate in Escherichia coli: a possible role for guanosine tetraphosphate. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2013–2019. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.2013-2019.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland JC. Regulation of chromosome replication in Bacillus subtilis: marker frequency analysis after amino acid starvation. Science. 1971;172:159–161. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3979.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donachie WD. Relationship between cell size and time of initiation of DNA replication. Nature. 1968;219:1077–1079. doi: 10.1038/2191077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durfee T, Hansen AM, Zhi H, Blattner FR, Jin DJ. Transcription profiling of the stringent response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/JB.01092-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferullo DJ, Lovett ST. The stringent response and cell cycle arrest in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant J, Irr J, Cashel M. The mechanism of amino acid control of guanylate and adenylate biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:5812–5816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MT, Pato ML, Molin S, Fill NP, von Meyenburg K. Simple downshift and resulting lack of correlation between ppGpp pool size and ribonucleic acid accumulation. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:585–591. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.2.585-591.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Morooka N, Yamamoto Y, Fujita K, Isono K, Choi S, Ohtsubo E, Baba T, Wanner BL, Mori H, Horiuchi T. Highly accurate genome sequences of Escherichia coli K-12 strains MG1655 and W3110. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100049. 2006.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NS, Kadoya R, Chattoraj DK, Levin PA. Cell size and the initiation of DNA replication in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjee U, Gutsche I, Alexopoulos E, Zhao B, El Bakkouri M, Thibault G, Liu K, Ramachandran S, Snider J, Pai EF, Houry WA. Linkage between the bacterial acid stress and stringent responses: the structure of the inducible lysine decarboxylase. EMBO J. 2011;30:931–944. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T. Feedback controls restrain the initiation of Escherichia coli chromosomal replication. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:9–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keasling JD, Bertsch L, Kornberg A. Guanosine pentaphosphate phosphohydrolase of Escherichia coli is a long-chain exopolyphosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7029–7033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodursky AB, Peter BJ, Schmid MB, DeRisi J, Botstein D, Brown PO, Cozzarelli NR. Analysis of topoisomerase function in bacterial replication fork movement: use of DNA microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9419–9424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriel A, Bittner AN, Kim SH, Liu K, Tehranchi AK, Zou WY, Rendon S, Chen R, Tu BP, Wang JD. Direct Regulation of GTP Homeostasis by (p)ppGpp: A Critical Component of Viability and Stress Resistance. Mol Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lark KG, Lark C. Regulation of chromosome replication in Escherichia coli: a comparison of the effects of phenethyl alcohol treatment with those of amino acid starvation. J Mol Biol. 1966;20:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(66)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini RA, Cashel M, Gallant J. On the regulation of guanosine tetraphosphate levels in stringent and relaxed strains of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:4381–4385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JB, Hite RK, Hamdan SM, Xie XS, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. DNA primase acts as a molecular brake in DNA replication. Nature. 2006;439:621–624. doi: 10.1038/nature04317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Vannier F, Dehbi M, Henckes G, Seror SJ. The stringent response blocks DNA replication outside the ori region in Bacillus subtilis and at the origin in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:605–613. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90657-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Chao S, Bremer H. Effect of relA function on the replication of plasmid pBR322 in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:150–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00330396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JM, Dromerick A, Freese E. Response of guanosine 5'-triphosphate concentration to nutritional changes and its significance for Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:605–613. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.605-613.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciag M, Kochanowska M, Lyzen R, Wegrzyn G, Szalewska-Palasz A. ppGpp inhibits the activity of Escherichia coli DnaG primase. Plasmid. 2010;63:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. The annals of mathematical statistics. 1947;18:50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh RC, Hepburn ML. Inititation and termination of chromosome replication in Escherichia coli subjected to amino acid starvation. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:236–242. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.1.236-242.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry CS. Chromosomal replicases as asymmetric dimers: studies of subunit arrangement and functional consequences. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1157–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia coli and Related Bacteria. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pizer LI, Merlie JP. Effect of serine hydroxamate on phospholipid synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:980–987. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.980-987.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz RT, O'Donnell M. Replisome mechanics: insights into a twin DNA polymerase machine. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possoz C, Filipe SR, Grainge I, Sherratt DJ. Tracking of controlled Escherichia coli replication fork stalling and restart at repressor-bound DNA in vivo. Embo J. 2006;25:2596–2604. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rymer RU, Solorio FA, Tehranchi AK, Chu C, Corn JE, Keck JL, Wang JD, Berger JM. Binding Mechanism of MetalNTP Substrates and Stringent-Response Alarmones to Bacterial DnaG-Type Primases. Structure. 2012;20:1478–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders GM, Dallmann HG, McHenry CS. Reconstitution of the B. subtilis replisome with 13 proteins including two distinct replicases. Mol Cell. 2010;37:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer P, Millet J, Aubert JP. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965;54:704–711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.3.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider DA, Murray HD, Gourse RL. Measuring control of transcription initiation by changing concentrations of nucleotides and their derivatives. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:606–617. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber G, Metzger S, Aizenman E, Roza S, Cashel M, Glaser G. Overexpression of the relA gene in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3760–3767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber G, Ron EZ, Glaser G. ppGpp-mediated regulation of DNA replication and cell division in Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:27–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00294520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons LA, Breier AM, Cozzarelli NR, Kaguni JM. Hyperinitiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli leads to replication fork collapse and inviability. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:349–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville CR, Ahmed A. Mutants of Escherichia coli defective in the degradation of guanosine 5'-triphosphate, 3'-diphosphate (pppGpp) Mol Gen Genet. 1979;169:315–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00382277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira B, Silberstein N, Yagil E. Guanosine 3',5'-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp) synthesis in cells of Escherichia coli starved for Pi. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4053–4058. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4053-4058.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehranchi AK, Blankschien MD, Zhang Y, Halliday JA, Srivatsan A, Peng J, Herman C, Wang JD. The transcription factor DksA prevents conflicts between DNA replication and transcription machinery. Cell. 2010;141:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautinger BW, Jaktaji RP, Rusakova E, Lloyd RG. RNA polymerase modulators and DNA repair activities resolve conflicts between DNA replication and transcription. Mol Cell. 2005;19:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBogelen RA, Neidhardt FC. Ribosomes as sensors of heat and cold shock in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5589–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasantha N, Freese E. Enzyme changes during Bacillus subtilis sporulation caused by deprivation of guanine nucleotides. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:1119–1125. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.3.1119-1125.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinella D, Albrecht C, Cashel M, D'Ari R. Iron limitation induces SpoT-dependent accumulation of ppGpp in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:958–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JD, Sanders GM, Grossman AD. Nutritional control of elongation of DNA replication by (p)ppGpp. Cell. 2007;128:865–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biometrics Bulletin. 1945;1:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow RM. A consequence of the rel gene during a glucose to lactate downshift in Escherichia coli. The rates of ribonucleic acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:4872–4877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CA, Zechner EL, Marians KJ. Coordinated leading- and lagging-strand synthesis at the Escherichia coli DNA replication fork. I. Multiple effectors act to modulate Okazaki fragment size. J Biol Chem. 1992a;267:4030–4044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CA, Zechner EL, Reems JA, McHenry CS, Marians KJ. Coordinated leading- and lagging-strand synthesis at the Escherichia coli DNA replication fork. V. Primase action regulates the cycle of Okazaki fragment synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1992b;267:4074–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J, Jakimowicz D, Zawilak-Pawlik A, Messer W. Regulation of the initiation of chromosomal replication in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31:378–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner EL, Wu CA, Marians KJ. Coordinated leading- and lagging-strand synthesis at the Escherichia coli DNA replication fork. II. Frequency of primer synthesis and efficiency of primer utilization control Okazaki fragment size. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4045–4053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.