Abstract

The paired-box homeodomain transcription factor Pax3 is a key regulator of the nervous system, neural crest and skeletal muscle development. Despite the important role of this transcription factor, very few direct target genes have been characterized. We show that Itm2a, which encodes a type 2 transmembrane protein, is a direct Pax3 target in vivo, by combining genetic approaches and in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. We have generated a conditional mutant allele for Itm2a, which is an imprinted gene, by flanking exons 2–4 with loxP sites and inserting an IRESnLacZ reporter in the 3′ UTR of the gene. The LacZ reporter reproduces the expression profile of Itm2a, and allowed us to further characterize its expression at sites of myogenesis, in the dermomyotome and myotome of somites, and in limb buds, in the mouse embryo. We further show that Itm2a is not only expressed in adult muscle fibres but also in the satellite cells responsible for regeneration. Itm2a mutant mice are viable and fertile with no overt phenotype during skeletal muscle formation or regeneration. Potential compensatory mechanisms are discussed.

Introduction

Pax genes, which encode paired domain transcription factors, play key roles in tissue specification and organogenesis during embryonic development [1]. Pax3 mutant embryos have defects in neural tube closure, severely reduced neural crest migration in the trunk and skeletal muscle defects. Mesodermal expression of Pax3 is first detected in presomitic mesoderm and then in somites where it becomes restricted to the dorsal dermomyotome. Multipotent Pax3-positive cells of the dermomyotome give rise to a number of derivatives, including the skeletal muscle of the trunk and limbs. Cells, that have activated the myogenic determination genes, Myf5 and Mrf4, delaminate from the edges of the dermomyotome to form the first muscle mass, the myotome, beneath the dermomyotome. At limb level, Pax3-positive cells, that have not yet entered the myogenic program, migrate into the limb bud where they provide the progenitor cell pool for skeletal myogenesis. In the absence of Pax3, limb muscles are absent, cells fail to migrate from the hypaxial dermomyotome and this domain of the somite undergoes apoptosis. Pax7, a closely related paralogue of Pax3, is also expressed in the central domain of the dermomyotome, as well as in myogenic progenitors when they reach the limb. As the somite matures, the central domain of the dermomyotome loses its epithelial structure and Pax3/Pax7-positive myogenic progenitors enter the underlying muscle mass of the myotome, which later expands and segments to give rise to the muscles of the trunk. The Pax3/Pax7 population provides a reserve of myogenic progenitors for all subsequent muscle growth. In the Pax3/Pax7 double mutant, these cells fail to enter the myogenic program, and many of them die [2]. This population is also the source of postnatal myogenic progenitors, known as satellite cells because of their characteristic position under the basal lamina of the muscle fiber [3], [4]. Pax7 marks the majority of satellite cells [5], many of which also continue to transcribe Pax3 [6]. In addition to contributing to post-natal growth, these cells are also the main source of progenitors for adult muscle regeneration [7], [8]. In the adult, satellite cells are mainly quiescent, undergoing activation on injury when they express the myogenic determination factors Myf5 and MyoD, proliferate and then differentiate to form new fibers. As in the embryo, the differentiation process is initiated by expression of the myogenic differentiation factor, Myogenin, and cell cycle withdrawal. Pax7/3 are down-regulated prior to the onset of differentiation, or remain expressed in cells that reconstitute the satellite cell pool.

Pax3, and later also Pax7, thus plays a key role in skeletal myogenesis [1]. Mutant phenotypes indicate its function in this context in the embryo, - in somitogenesis, delamination and migration of cells from the dermomyotome, cell survival/proliferation and the entry of progenitor cells into the myogenic program -, yet very few direct Pax3 target genes have been identified. The gene encoding the tyrosine kinase receptor, c-Met, has been described as a Pax3 target [9] and c-met mutants lack all muscles of migratory origin [10]. A critical enhancer element, upstream of the Myf5 gene, is directly activated by Pax3 [11] and Pax7 targets a regulatory sequence of the MyoD gene [12]. Since the binding sites for Pax3 and Pax7 are similar [13], both factors probably activate common targets, as shown for Pax7 on the Myf5 enhancer [14]. Fgfr4, involved in the self-renewal versus differentiation of muscle progenitors, is also directly regulated by Pax3 through a 3′ myogenic enhancer element [15]. Other potential targets have come from genetic screens. Since cells tend to undergo apoptosis in the absence of Pax3, gain of function rather than loss of function comparisons have been particularly valuable. PAX3 and PAX7 are implicated in Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS), a pediatric tumour of skeletal muscle origin that results from a translocation between PAX3/7 and FKHR (FOXO1A). This generates a hybrid transcription factor, PAX-FKHR, which binds and transactivates PAX3/7 target genes, leading to their over-expression [16]. A number of screens based on over-expression of Pax3/7 in cultured cells have been carried out [17], [18]. CASTing experiments with cyclic amplification and selection of genomic sequences bound by PAX3, PAX3-FKHR [19] or a large scale ChIP-seq screen for PAX3-FKHR binding sites in ARMS cells [20] have also led to lists of potential targets. We constructed a Pax3PAX3-FKHR/+ allele and showed that in Pax3PAX3-FKHR/+ embryos, c-met for example, as well as Myf5 and MyoD, are up-regulated [21]. This allele rescues the Pax3 mutant phenotype and we therefore devised a screen incorporating a Pax3GFP allele [21] which permits us to purify the Pax3-positive population by flow cytometry. Comparison of the transcriptome of somites at E9.5 and forelimb buds at E10.5 of Pax3GFP/+ and Pax3GFP/PAX3-FKHR embryos led to the identification of genes that are up- or down-regulated in the presence of FKHR [22]. These included known Pax3 targets and genes such as Foxc2, implicated in cell fate decisions in the dermomyotome [23], which is negatively regulated by Pax3. Among the genes that are up-regulated (2.79, 3.27 fold in limb buds and somites, respectively) on the gain of function, Pax3PAX3-FKHR, background in our in vivo screen was Itm2a, also identified in several of the in vitro screens. In this study, we show that Itm2a is a direct Pax3 target in vivo and examine its role in myogenesis.

Itm2a is expressed in the C2C12 muscle cell line where its mRNA increases on differentiation and over-expression leads to muscle creatine kinase up-regulation and more myotube formation [24]. This is in contrast to the chondrocyte model where over-expression of Itm2a delayed the onset of differentiation [25]. Expression studies in cell lines suggest that Itm2a is associated with early stages of the chondrogenic program.

Itm2a encodes a transmembrane protein, which, in addition to a transmembrane domain, has a Brichos domain of about 100 amino acids, potentially acting as a chaperone domain [26]. This Brichos domain has been identified in several previously unrelated proteins that are linked to major human diseases such as dementia, respiratory distress and cancer [27]. The Brichos domain is potentially associated with anti-apoptotic functions. Mutation of the Brichos domain of a surfactant protein (SP-C) causes proteasome dysfunction and caspase 3/4 activation leading to apoptosis [28].

In this study, we have investigated the expression and potential role of Itm2a during myogenesis in the mouse embryo and during muscle regeneration in the adult. We establish that Itm2a lies genetically downstream of Pax3 and confirm that it is a direct target by ChIP assays on embryonic extracts. In order to investigate function we made a conditional mutant allele of Itm2a, incorporating an nLacZ reporter. The expression profile of the reporter confirms that Itm2a is transcribed at sites of myogenesis, both in the embryo and the adult. The Itm2a mutant has no detectable myogenic phenotype.

Results

Itm2a Expression is Modulated by Pax3 and Myf5 during Development

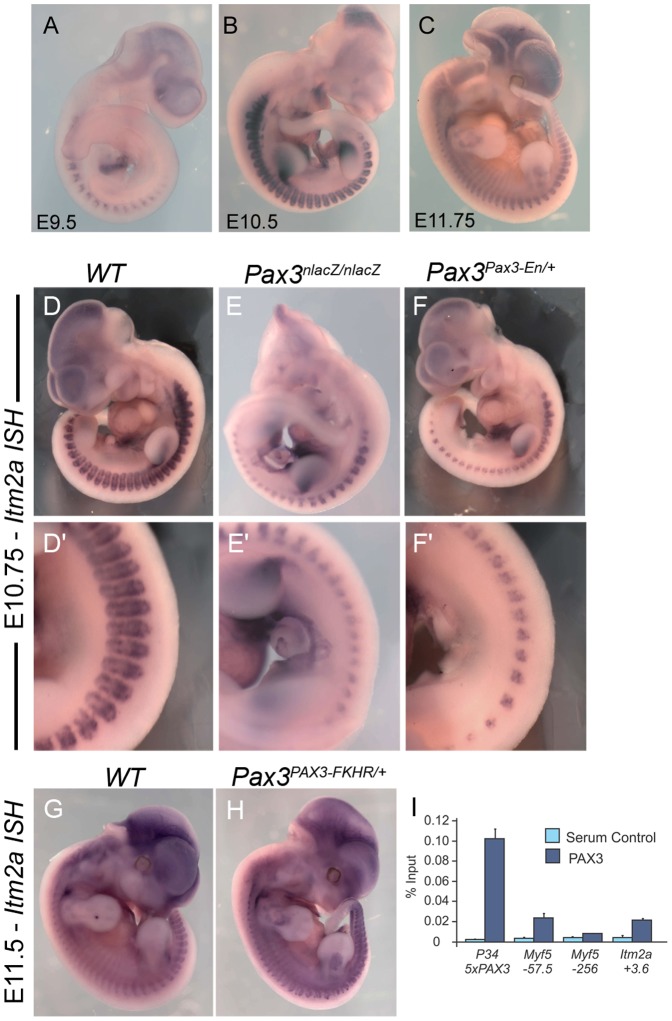

The gene encoding the transmembrane protein Itm2a emerged as a potential Pax3 target in myogenic progenitors in the mouse embryo [22]. To characterize Itm2a expression during mouse development, whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed on wild-type mouse embryos from Embryonic day (E) 9.5 to 11.75 (Figure 1 A–C). At E9.5, expression of Itm2a is detected in the somites, heart and brain (Figure 1A). Expression at these sites is maintained at E10.5 and E11.75, with additional expression in the forelimb bud at sites of chondrogenesis at E10.5 and of myogenesis, as clearly distinguished at E11.75 (Figure 1B–C), as well as in the pharyngeal arches (Figure 1B). The sites of somitic expression (Figure 1 and data not shown) suggest expression in the dermomyotome as well as in the myotome.

Figure 1. Itm2a is a novel Pax3 target.

A–C, Whole mount in situ hybridization with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe at E9.5 (A), E10.5 (B) and E11.75 (C). D–F’, Whole mount in situ hybridization with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe on wild type (WT) (D, D’), Pax3nLacZ/nLacZ (E, E’) and Pax3Pax3-En/+ (F, F’) embryos at E10.5. D’–F’ show close-ups of the interlimb somite region. As expected, the modification of Itma transcription in the mutant is restricted to Pax3-expressing cells. G–H, Whole mount in situ hybridization with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe on wild type (WT) and Pax3PAX3-FKHR/+ embryos at E11.5. I, Real-time quantitative PCR using primers for the putative Pax3 binding site identified in [19] in the Itm2a sequence at +3.6 kb. The 5 Pax3-binding sites in the P34 transgene [21] and a functional Pax3 site at −57.5 kb from the Myf5 gene [11] provide positive controls. A Myf5 flanking sequence at −256 kb that does not bind Pax3 [11] provides a negative control. Results are expressed as a percentage of PCR signal on input DNA, showing enrichment after Pax3 immunoprecipitation, or with an IgG antibody.

In order to validate genetically that Itm2a is a Pax3-regulated gene, we perfomed in situ hybridization on embryos carrying modified Pax3 alleles.

In Pax3-mutant embryos, Itm2a expression is strongly reduced (Figure 1E–E’), however, apoptosis in the epaxial and, notably, the hypaxial dermomyotome of the somite complicates interpretation [1]. In the presence of the allele for Pax3Pax3-En which encodes a fusion protein in which the DNA binding domain of Pax3 is fused to the Engrailed repressor domain, heterozygote Pax3Pax3-En/+ embryos have a partial loss of Pax3 function [11]. In these embryos Itm2a expression is severely impaired at E10.5 in the somitic region (Figure 1F–F’), a phenotype readily seen from E9.5 (data not shown). At these early stages, most Pax3-positive cells are still present in the somite of Pax3Pax3-En/+ embryos, excluding this reduced expression as secondary to loss of cells [11] (Figure S1). Moreover, this epistatic regulation is specific since the expression of Itm2a is only affected at sites of Pax3 expression in our mouse models (Fig. 1E–F’). Conversely, in the presence of a Pax3PAX3-FKHR gain of function allele, which encodes a fusion protein in which the DNA binding domain of the human PAX3 protein is fused to the transcriptional activation domain of FKHR (FOXO1A) [21], Itm2a expression is increased in the somites, and in the skeletal muscle cells of the limbs of Pax3PAX3-FKHR/+ embryos as shown at E11.5 (Figure 1G–H, Figure S2). Altogether, our data validate the results of the transcriptome analysis [22] and confirm that Itm2a limb-expression is not restricted to sites of chondrogenesis but that it is also expressed at sites of myogenesis in the proximal limb bud (ex. Figure 1H).

Residual expression of Itm2a in the absence of Pax3 (Figure 1E) suggests that Pax7 may also activate this gene. To test this hypothesis, Itm2a expression was evaluated in embryos where Pax7-IRESnLacZ replaces Pax3. In Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/Pax7-IRESnLacZ embryos, Pax7 is able to substitute for all Pax3 functions during trunk myogenesis but specific defects are observed in the limbs [13]. In the absence of endogenous Pax3, and in the presence of additional Pax7 from the Pax3 allele in Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/Sp mice, somitic expression of Itm2a is decreased, notably at the hypaxial level where Pax3 plays a critical role [1] (Figure S3). However, since some expression is still detected in the absence of Pax3, we conclude that Itm2a lies genetically downstream of both Pax3 and Pax7 at sites of myogenesis, but that Pax3 is a stronger activator of its expression.

Since Itm2a is expressed in developing skeletal muscle, we analyzed its expression in Myf5nLacZ/nLacZ mice in which the myogenic determination factors Myf5 and Mrf4 are absent [29], [30]. In these mutant embryos, myogenic progenitor cells are blocked at the edges of the dermomyotome and no myotome is formed until the activation of MyoD, from E11.5 [31]. In the absence of myogenesis, expression of Itm2a is barely detectable at E10.75 (Figure S4) and strongly reduced at E11 (Figure S4). These data therefore suggest that Itm2a is regulated by both Pax3 and Myf5/Mrf4, which have parallel functions in the establishement of the primary myotome [31], or that Itm2a expression in the somite by this stage is mainly in the differentiating muscle cells of the myotome, which start to be rescued by MyoD expression in the mutant from E11.

Itm2a is a Direct Pax3 Target Gene in vivo

Genetic studies therefore suggest that Itm2a is a downstream target of Pax3/7 but do not demonstrate whether this regulation is direct. A putative Pax3 binding site has been reported in the first intron of the Itm2a gene and gel mobility shift assays suggested that Pax3 can directly bind this sequence in vitro and transactivate it in cell lines [19]. We tested this putative binding site for Pax3 binding in vivo using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) on chromatin from crosslinked cells within pools of E11.5 embryonic trunk and limbs. (Figure 1I) [15]. Results of quantitative PCR using this binding site, compared to the 5 Pax3 binding sites of the P34 transgene [21] or the binding site of the Myf5 enhancer at −57.5 Kb, as positive controls [11], shows that Pax3 enrichment of the Itm2a sequence is approximately equivalent to that of the Myf5 −57.5 kb sequence. This demonstrates that this region in the first intron of Itm2a is bound by the Pax3 protein in vivo.

The antibody used for immuno-precipitation can also recognize Pax7, therefore, as suggested by the genetic studies (Figure S3), Pax3 binding sites located in the first intron of Itm2a may also be bound by Pax7. Recent Chip-Seq experiments, performed on cultured myoblasts also reveal Pax7 binding to Itm2a (however these are not located within the 1st intron) [32].

An Itm2a Conditional Allele Incorporating a LacZ Reporter

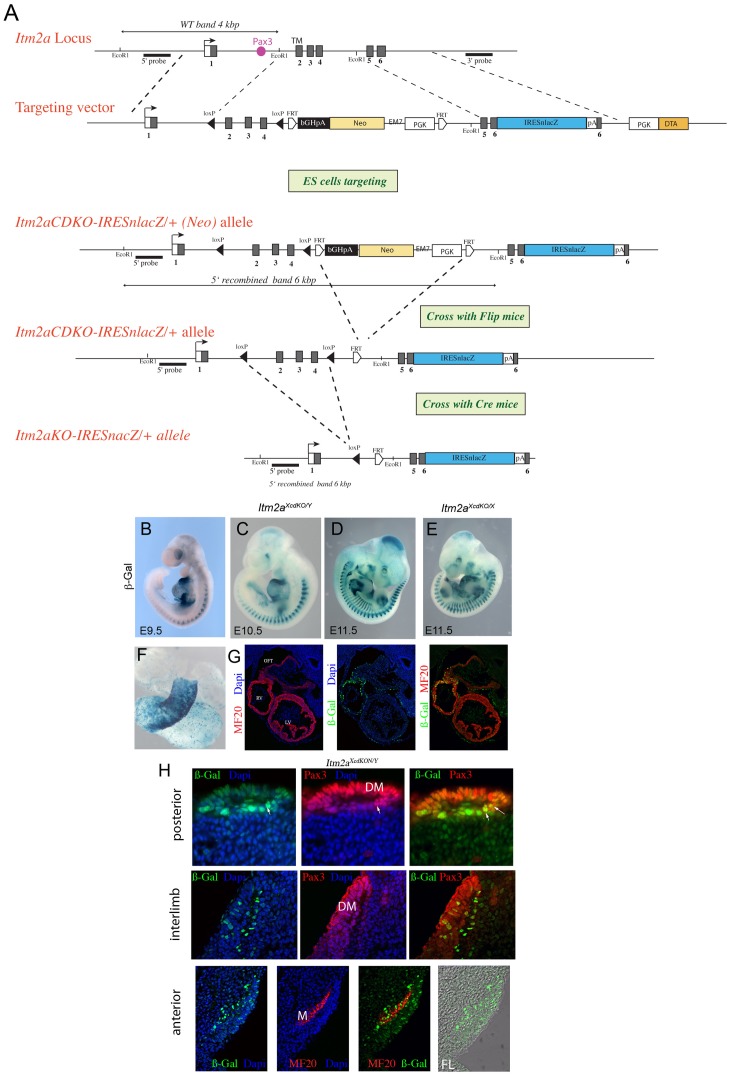

In order to study Itm2a function in vivo, the Itm2a gene was targeted by homologous recombination. A conditional approach has been adopted to avoid potential precocious embryonic lethality. LoxP sites were introduced before and after exons 2–4 so that the transmembrane domain is removed and the Brichos domain is compromised on crossing with a mouse line expressing Cre recombinase. An IRESnLacZ reporter, which encodes β-Galactosidase (β-Gal), placed downstream of an internal ribosome entry site (IRES), has also been inserted into the 3′UTR of the gene, in order to follow Itm2a expressing or mutant cells. The targeting strategy is illustrated in the scheme shown in Figure 2A. The Pax3 binding site is located 5′ to the floxed region.

Figure 2. Generation of an Itm2a conditional reporter allele.

A. Schematic diagram of the Itm2a locus and targeting construct. The construct contains loxP sites inserted into exon 1 and 4. A PGK-Neo-pA (Neo) selection marker is flanked by FRT sites and inserted into exon 4. An IRES-nLacZ cassette has been inserted into the 3′ UTR (exon 6). A counter-selection cassette encoding the A subunit of Diphtheria Toxin was inserted at the 5′ end of the targeting vector. Schematic diagrams of the Itm2acdKO-IRESnLacZ (Neo) and Itm2aKO-IRESnLacZ (Neo) alleles are also shown. Probes and restriction enzymes are indicated, with the size of the resulting wild-type and recombined restriction fragments. Pax3 sites located in Itm2a intron1 are represented by a pink box. B–D, X-Gal stained Itm2aXcdKO/Y embryos at E9.5 (B), E10.5 (C) and E11.5 (D). E, An X-Gal stained Itm2aXcdKO/X embryo at E11.5. Note the chimeric expression of the reporter, due to random X inactivation. F, An isolated X-Gal stained heart of an Itm2aXcdKO/Y embryo at E9.5. G, Immunohistochemistry on transverse sections through the heart region of an E9.5 Itm2aXcdKO/Y embryo using antibodies recognizing striated muscle myosin MF20 (red), β-Gal (green). Dapi staining of nuclei is in blue. The right hand panel shows a merged image with both antibodies. OFT, outflow tract; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle. H, Immunohistochemistry on transverse sections through immature somites of an Itm2aXcdKO/Y embryo at E10.5, in the more caudal region (top), in the interlimb region (middle) and just anterior to the forelimb (bottom), using antibodies recognizing Pax3 or striated muscle myosin (MF20) (red) as indicated on the Figure, and β-Gal (green). Dapi staining of nuclei is in blue. Merged images are shown on the right. In the bottom series, the right hand panel shows phase contrast with β-Gal on a somite just anterior to the forelimb bud. Dermomyotome (DM), Myotome (M), Forelimb (FL). Arrows point to cells expressing Pax3 and ßGal (Itm2a).

After generation of chimaeric mice and germline transmission, adult males or females carrying either the conditional Itm2aXcdKON (which contains the Neo selection cassette) or Itm2aXcdKO (with the Neo selection cassette removed) alleles, were viable and fertile and did not present any obvious phenotype. Itm2a is located on the X chromosome, which is why a nomenclature showing the X/Y genotype has been adopted in this study: Itm2aXcdKO/Y for male and Itm2aXcdKO/XcdKO for female embryos.

In order to validate the expression profile from the IRESnLacZ reporter, the X-Gal profile of Itm2AXcdKO/Y male embryos from E9.5 to E11.5 was compared to endogenous Itm2a expression. As shown at E9.5, E10.5 and E11.5, β-Galactosidase activity from the nLacZ reporter (Figure 2B–D) follows endogenous Itm2a expression (Figure 1). Strikingly, Itm2AXcdKO/X female embryos show a chimaeric expression of the nLacZ reporter at all sites of Itm2a expression, as shown at E11.5 (Figure 2E, see also Figure S5). This phenomenon is probably due to random X-inactivation in female embryos (reviewed in [33]), resulting in a mosaic expression of the wild-type and engineered alleles (Figure S5). In the case of a conditional mutated allele, the recombined allele should not significantly perturb the inactivation pattern, and indeed previous gene targeting in mice already reported mosaicism of reporter expression in female embryos (for example with Sox3 targeting [34]). Altogether these results validate the targeting of the Itm2a locus, showing that the nlacZ reporter follows endogenous Itm2a gene expression, with random X-inactivation in female embryos.

In addition to skeletal muscle, the expression of Itm2a was documented previously in two main tissues: bone [35] and thymus [36]. In the developing skeletal system, Itm2a expression has been reported in areas undergoing endochondral ossification, more specifically in chondrocytes of the resting and proliferating zones [37], in keeping with the profile of nLacZ expression that we observe (Figure S6). The nLacZ reporter also reveals other sites of expression, such as the developing heart, where β-Galactosidase positive cells are notably present in the outflow tract and right ventricle, which are derivatives of the anterior part of the second heart field [38] (Figure 2F–G).

In order to determine in which cells of the developping somite Itm2a is expressed, and because we could not find a reliable antibody against Itm2a protein that works for immunohistochemistry, we relied on the β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) protein to follow Itm2a expression. At an early stage of somite development, in more posterior somites at E10.5, β-Gal (Itm2a) expression is detected in the dermomyotome marked by Pax3, and in the underlying cells of the myotome that are undergoing skeletal muscle differentiation (Figure 2H upper panels). In more developed interlimb somites and in anterior somites, β-Gal (Itm2a) expression is restricted to a subset of cells in the dermomyotome as well as the myotome (Figure 2H middle and lower panels).

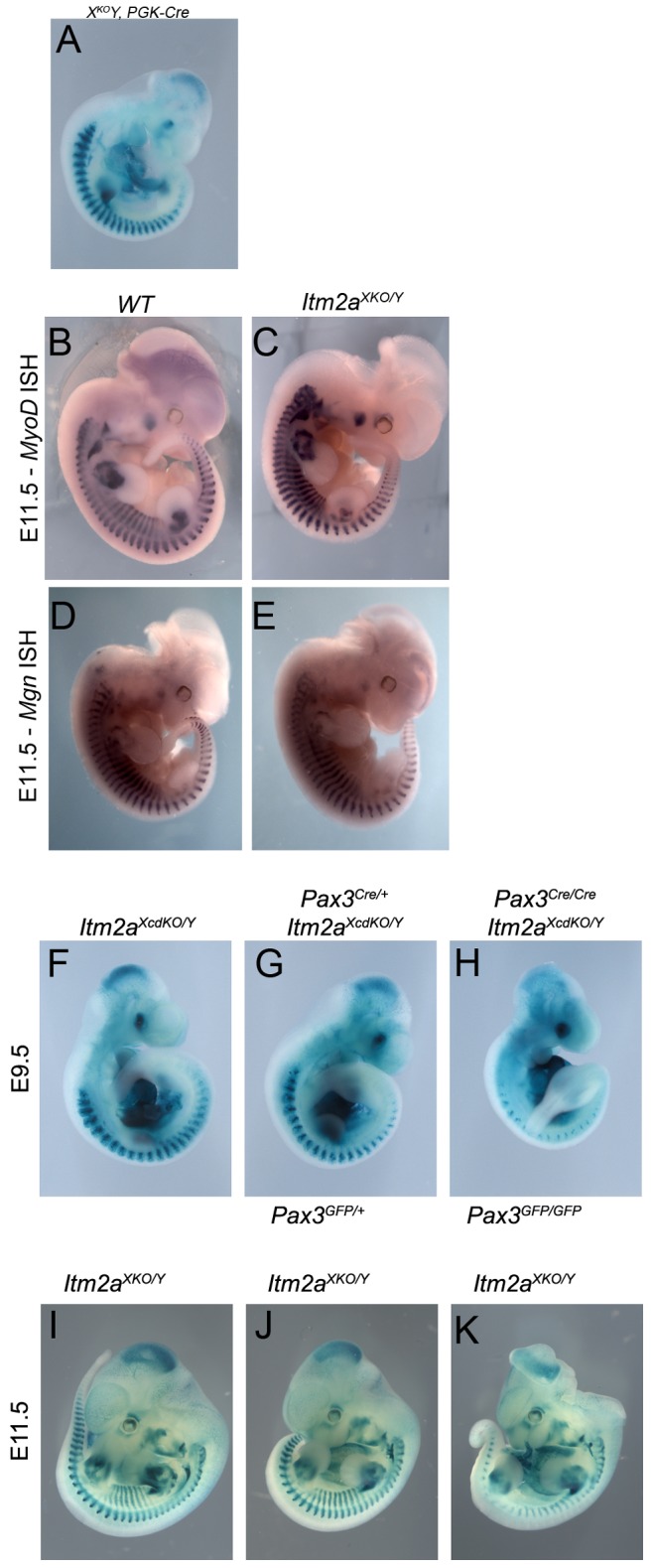

Itm2a is Dispensable for Embryonic Development and Myogenesis

As shown above, we designed the Itm2aXcdKO allele so that it can be used to generate an Itm2a loss of function allele when intercrossed with mice expressing ubiquitous or tissue-specific Cre drivers. When Itm2AXcdKO/Y adult males were crossed with females carrying a maternally-expressed PGK-Cre transgene [39], we obtained viable Itm2AXKO/Y adult males and Itm2AXKO/X adult females in mendelian ratios. Itm2AXKO/Y; PGK-Cre male embryos expressed the nLacZ reporter at all sites of Itm2a expression, as shown at E10.5 (Figure 3A, Figure S7) and had no obvious phenotype. We also intercrossed Itm2AXKO/Y adult males and Itm2AXKO/X adult females to generate Itm2AXKO/XKO adult females, and again these animals were viable and fertile, with no evident phenotype. Next, we analyzed the expression of the myogenic determination gene, MyoD, and the myogenic differentiation gene, Myogenin, by in situ hybridization in Itm2AXKO/Y male (Figure 3B–E) and Itm2AXKO/XKO female embryos (data not shown). In both cases, myogenesis was not affected by the loss of Itm2a expression. In order to evaluate whether this absence of phenotype was due to an early compensatory mechanism, we mutated Itm2a at later stages, specifically in the myogenic lineage by crossing Itm2AXcdKO/Y adult males with Pax3Cre/+ females carrying an allele of Pax3 targeted with the Cre recombinase sequence [40]. Itm2AXcdKO/Y; Pax3Cre/+ males have a deletion of Itm2a in all Pax3-derived cell lineages, including all skeletal muscle of the trunk and limbs, the dorsal neural tube, and all neural-crest derived tissues [40]. Itm2AXcdKO/Y; Pax3Cre/+ males were viable, fertile and did not show any detectable phenotypes during development (Figure 3F–G). Finally, as Itm2a is a direct Pax3 target gene, we tested whether Pax3 and Itm2a interact genetically. Itm2AXcdKO/Y; Pax3Cre/+ males were crossed with Pax3Cre/+ females to generate Itm2AXcdKO/Y; Pax3Cre/Cre male double mutant embryos in the Pax3 lineage (Figure 3H), and Itm2AXKO/Y; Pax3GFP/+ males were crossed with Pax3GFP/+ females to generate Itm2AXKO/Y; Pax3GFP/GFP male double mutant embryos (Figure 3J). In both cases, the double-deficient embryos displayed a classic Pax3 mutant phenotype, but no additional phenotypes were observed (Figure 3 F–K, Figure S8).

Figure 3. Phenotypic analysis of Itm2a mutant embryos.

A, X-Gal staining of an Itm2aXKO/Y; PGK-Cre embryo at E10.5. B–E, Whole mount in situ hybridization with a MyoD (B–C) and Myogenin (D–E) antisense riboprobe on control (WT) (B, D) and Itm2aXKO/Y embryos at E11.5. In A, C and E the mice were crossed with the PGK-Cre line to delete the floxed Itma2 allele. F–H, X-Gal staining of Itm2aXcdKO/Y (F), Itm2aXcdKO/Y; Pax3Cre/+ (G) and Itm2aXcdKO/Y; Pax3Cre/Cre (H) embryos at E9.5. I–J, X-Gal staining of Itm2aXKO/Y (I), Itm2aXKO/Y; Pax3GFP/+ (J) and Itm2aXKO/Y; Pax3GFP/GFP (K) embryos at E11.5.

Itm2a is Expressed in Adult Skeletal Muscle

In adult mice, assay of Itm2a transcripts by Northern blot had shown that these are highest in the thymus and also expressed, at lower levels, in lymph nodes, spleen, brain, heart, lung, stomach and uterus [36]. Itm2a transcripts also accumulate in adult skeletal muscle, where the protein has been detected previously [41]. The link with Pax3/7 suggests that Itm2a might be expressed in adult skeletal muscle progenitor cells (satellite cells), however Itm2a expression had only been reported in muscle fibers [24]. The β-Gal reporter in our Itm2a allele provides a robust system to identify the cell types that transcribe Itm2a in adult skeletal muscle. First, we perfomed X-Gal staining on sections of EDL and Diaphragm skeletal muscle from adult Itm2AXcdKO/x mice. The reporter was expressed in nuclei located under the basal lamina of the muscle fiber, as well as in myonuclei within most fibers (90% in EDL, 64% in Diaphragm for both locations). We also detected expression in glial cells surrounding nerves (data not shown).

To examine more precisely the expression of Itm2a during adult myogenesis, we used a single fiber culture system [42]. We isolated single fibers from the EDL muscle of adult (8 weeks) Itm2AXcdKO/Y mice and fixed them immediately (T0). After immunohistochemistry, we detected the expression of the β-Gal reporter in quiescent satellite cells marked by Pax7 expression, at T0 (Figure 4A). Thus, Itm2a is a novel satellite cell marker. In addition to satellite cells, most fibers also showed expression of the β-Gal reporter in myonuclei (Figure 4B and E). This was also observed in other muscles examined (data not shown and see below). When isolated single fibers were maintained in culture for 48 h (T48) and 72 h (T72) (Figure 4D), the β-Gal reporter colocalized with MyoD (Figure 4C) and Myogenin (Figure 4D), demonstrating that Itm2a expression is maintained in activated, proliferating (MyoD-positive) and differentiating (Myogenin-positive), satellite cells.

Figure 4. Itm2a is expressed in adult skeletal muscles.

A–D, Immunohistochemistry on isolated single fibers from the EDL muscle of adult Itm2aXcdKO/Y mice immediately after isolation (T0) (A, B), or after 48 h, (T48) (C) or 72 h (T72) (D) culture, using Dapi staining (blue) and antibodies recognizing Pax7 (red, A, green B), β-Gal (green, A, C, D, red, B), MyoD (red, C) and Myogenin (red, D). Arrowheads point to Pax7-positive satellite cells (A,B). E, X-Gal staining for β-Gal on isolated single EDL fibers from adult Itm2aXcdKO/Y mice at T0 showing examples where the myonuclei are positive or negative. Dapi is shown in blue. X-Gal positive staining quenches DAPI. F, Immunohistochemistry on transverse sections of EDL muscle isolated from adult Itm2aXcdKO/Y mice with Dapi staining (blue), and antibodies recognizing Laminin (green) (left) or slow myosin heavy chain (red) and β-Gal (blue) (right) as indicated. G, Immunohistochemistry experiments on isolated single fibers from adult Itm2aXcdKO/Y and Itm2aXKO/Y mice after 48 h culture (T48) with Dapi (blue) and an antibody recognizing MyoD (red). H, Eosin-hematoxylin staining on transverse sections of the EDL muscle isolated from adult control Itm2aXcdKO/Y (top) and Itm2aXKO/Y (bottom) mice, 10 days after cardiotoxin injury (CTX) (right) or PBS injection (control) (left). Dapi staining (blue) marks nuclei. In G and H the mice were crossed with the PGK-Cre line to delete the floxed Itma2 allele.

Since Itm2a expression is detected within a subset of muscle fibers (Figure 4E), we investigated whether this expression was linked to the fiber type. The diaphragm contains mostly slow- and intermediate-twitch muscle fibers (types I and II, respectively). We therefore used a slow myosin antibody that detects type I fibers to perform colocalization experiments on diaphragm sections from Itm2aXcdKO/Y adult mice. A laminin antibody was used to outline the fibers and Dapi to mark nuclei. As shown in Figure 4F, we could not detect a correlation between the expression of the β-Gal reporter and the fiber type.

Finally, we investigated whether Itm2a could play a role during adult myogenesis. We isolated single fibers from Itm2aXcdKO/Y (control) and Itm2aXKO/Y (mutant) adult mice and performed single fiber culture experiments. Mutant as well as control satellite cells expressed MyoD within 24 h after activation as previously described [42] (results not shown), and after 48 h of culture (T48) (Figure 4G). No difference in behaviour could be detected in satellite cells with or without Itm2a. We also investigated whether Itm2a is involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. We performed Cardiotoxin-mediated injury of the EDL muscle and analyzed the regeneration process 10 days later. Itm2aXcdKO/Y (control) and Itm2aXKO/Y (mutant) adult mice displayed a similar extent of skeletal muscle regeneration, as evidenced by the formation of new fibers, maked by centrally located nuclei (Figure 4H).

We conclude that Itm2a marks satellite cells and myonuclei of most fibers but is dispensable for adult myogenesis.

Discussion

In this investigation of the role of Itm2a during skeletal muscle formation in vivo, we demonstrate that the Pax3 binding site in the first intron of the Itm2a gene [19] binds Pax3 in vivo, as demonstrated by ChIP experiments with embryonic extracts. We therefore conclude that Itm2a is a direct Pax3 target. The introduction of an nLacZ reporter into an allele of Itm2a permitted us to confirm the myogenic sites of expression, suggested by in situ hybridization with an Itm2a probe in the embryo. Itm2a is initially expressed in the Pax3-positive multipotent cells of the dermomyotome. Subsequently, it is mainly expressed in the differentiating muscle cells of the underlying myotome. In these cells, that no longer express Pax3, the myogenic determination factors, Myf5 and Mrf4, may maintain its transcription, suggested by the loss of Itm2a expression in the Myf5/Mrf4 mutant, as in the case of Fgfr4 [15]. Indeed E-box sequences (CANNTG) that can bind myogenic factors are also present in the sequence in the first intron of Itm2a, that binds Pax3 (results not shown). Itm2a is also expressed in the developing muscle masses of the limb bud and at other sites of myogenesis. Itm2a expression persists in the satellite cells of adult skeletal muscle, both in quiescent and activated states. Myonuclei in most muscle fibers remain β-Gal positive - a phenomenon which is not related to fiber type. This kind of heterogeneity, at present unexplained, was also seen in the sites of expression directed by the A17 Myf5/Mrf4 enhancer in adult muscle [43]. In mutant embryos in which Pax7 replaces Pax3 and in muscle satellite cells of the EDL muscle which are Pax7-positive, but not Pax3-positive, Itm2a is transcribed, indicating that both Pax transcription factors can activate the gene and indeed Itm2a continues to be expressed in both Pax3 and Pax7 (results not shown) mutant embryos. When these Pax factors are highest, in quiescent satellite cells, Itm2a transcripts are maximal [44]. In addition to sites of myogenesis and other known sites of Itm2a expression, we document expression in the developing heart in the outflow tract and right ventricle, which derive from the anterior second heart field [38].

In the conditional Itm2a mutant embryos that we have constructed, with both early (PGK-Cre) and Pax3-specific (Pax3Cre/+) activation of the Cre recombinase, there is no detectable phenotype in the mutants. All aspects of embryonic myogenesis take place as in wild type embryos and this is also the case for adult satellite cell behaviour in culture or during skeletal muscle regeneration. The conditional mutation eliminates most of the coding exons of the Itm2a gene, including the transmembrane and a large part of the Brichos domain. RT-PCR analysis indicates that a truncated transcript is produced, as indeed shown by continuing expression of the IRES-nLacZ reporter integrated into the 3′ UTR of the gene. It is very unlikely that this truncated transcript leads to the accumulation of a partial Itm2a protein that can compensate for the function of Itm2a. An alternative explanation of the lack of a phenotype lies in potential compensation by other members of the Itm2a gene family. Itm2b and Itm2c share 38–45% homology with Itm2a, mainly in the -COOH terminal domain. Expression of Itm2c is restricted to the brain [45], whereas Itm2b is ubiquitously expressed [46]. In a differential screen on Interleukin 2 (IL-2) deprived or stimulated cells, Itm2b emerged as a gene induced on IL-2 deprivation [47]. Further analysis showed that Itm2b has a BH-3 domain that characterizes Bcl2 family members, in which this domain is essential for induction of apoptosis. Itm2b interacts with Bcl2 in vitro. It is unclear whether this pro-apoptotic function is shared by Itm2a, however when the coding sequences are compared no conservation of the BH-3 domain was observed. In contrast the Brichos domain, potentially associated with anti-apoptotic functions [28] is highly conserved. In Itm2a mutants, we did not detect transcripts of Itm2c or any up-regulation of Itm2b, the expression of which is at a barely detectable level, at sites of myogenesis in the embryo, although both Itm2c and Itm2b transcripts are detected with transcripts for Itm2a in quiescent satellite cells [44]. It is of course possible in the embryo that the basal level of Itm2b transcription, or the presence of other proteins with a Brichos domain or with other features of Itm2a, compensate for the absence of Itm2a. Itm2a and related transmembrane proteins may well play a role as adaptors in promoting membrane receptor function and/or in transmitting signals either through intracellular pathways that connect with the Brichos domain, or directly by the intervention of Itm2a intracellular domains after cleavage on the membrane. Further investigation of the proteins that interact with Itm2a at sites of myogenesis in vivo will be required to throw more light on the role of Itm2-like proteins during myogenesis.

In conclusion, we have shown that Itm2a is a direct Pax3 target in vivo during myogenesis in the mouse embryo. Moreover, during adult skeletal myogenesis, Itm2a is a new satellite cell marker. Finally, we have generated a conditional floxed allele of Itm2a which is available for further genetic re-combination studies.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Statement

All experiments with mice reported in this paper were performed in the Monod animal house of the Pasteur Institute, under the control of individuals with an animal experimentation license, according to the regulations of the French Ministry of Agriculture. The Monod animal house is subject to agreement number B75-15-05 from the prefecture of Police. This includes provision for supervision by the internal ethics committee for animal experimentation of the Pasteur Institute.

Gene Targeting

Briefly, a region encompassing exons 2, 3 and 4 has been flanked by loxP sites. Under Cre recombinase activity, this sequence should be deleted, and since it contains the transmembrane as well as most of the Brichos domain, the transcript generated from the recombined allele should lead to a truncated non-functional protein. The reporter cassette has been inserted in the 3′ flanking region of exon 6 and an IRES (Internal-Ribosomal-Entry-Site) sequence has been used to allow the formation of a bi-cistronic RNA. The Neo selection cassette is flanked by FRT sites, allowing for its deletion by Flip recombinase activity.

The Itm2a gene is located in the syngenic region of the X chromosome [46]. We decided therefore to apply the following code for naming the different genotypes: Itm2aXcdKON/Y for males (no Cre, no Flip) and Itm2aXcdKON/X for females, sometimes simplified as Itm2acdKON/+. After Neo removal, the conditional allele is named cd (cd, for conditional), and after Cre recombinase deletion, this leads to a knock-out allele, named KO.

A total number of 949 embyonic stem (ES) cell clones were tested for homologous recombination, using a 5′ probe, by the Southern blotting technique as a first test (data not shown). Positive 5′-tested clones were then checked using a 3′ probe, but the results were unsatisfatory. Therefore homologous recombination in the 3′ region was checked by long template PCR. Two clones were correctly recombined, and one of them was injected into blastocysts obtained from C57/Bl6:DBA2 F1 mice. Chimera were obtained and their progeny (F0) were then tested in the 3′ recombined region using long template DNA, to demonstrate that the recombined allele has been correctly transmitted to the germ line. Heterozygote mice were then intercrossed with C57/Bl6 mice for 4–8 generations.

Breeding Mutant Mice and Genotyping

The following mouse lines were used: Pax3PAX3-FKHR-IRESnlaZ/+ (referred to as Pax3PAX3-FKHR/+), Pax3Pax3-En-IRESnLacZ/+ (referred to as Pax3Pax3-En/+), Myf5nLacZ/+, Pax3nLacZ/+, Pax3GFP/+ and Pax3Cre/+. Embryos were genotyped as described previously: Pax3PAX3-FKHR and Pax3nLacZ [21], Pax3Pax3-En [11], Pax3GFP/+ [2] and Pax3Cre/+ [40]. Pax3 lines have been maintained in a C57/Bl6 background. Myf5 mutant mice are maintained in a mixed background.

Dissection and Embryo Preparation

Embryos were collected after natural overnight mating and dated, taking Embryonic day (E) 0.5 as the day after the appearance of the vaginal plug. Briefly, embryos were fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde at 4°C, overnight for in situ hybridization, 2 hours for immuno-detection and 15 minutes for X-Gal staining.

In situ Hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations with digoxigenin-labeled probes were performed as described in [31]. The Itm2a probe was synthesized using the image clone 3469636 (Open Biosystems) and linearized by BamH1 enzyme digestion.

Real-time PCR

All PCR reactions were carried out in duplicate (triplicate for the standard curves) using the iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) [15] and an iCycler (Bio-Rad) thermal cycler.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Pax3 ChIP was performed on trunk and limb cells that had been crosslinked with formaldehyde from the P34 transgenic line at E11.5, as described in [15].

The previously identified binding site for Pax3, located within the first intron of Itm2a [19] was tested for in vivo Pax3 binding using ChIP-qPCR with the primers listed below.

Itm2a: forward: TTTGTGAGATTCGGTGTAGTTGA

Reverse: TTCAGAGAAGCGGCAATAGAA

Primers for P34 and Myf5 sequences are described in [15].

Immunohistochemistry

Fluorescent co-immunohistochemistry on sections was carried out as described previously [15]. The following antibodies were used: anti-Pax3 (monoclonal, DSHB, dilution 1/250), anti-MF20 (monoclonal, DSHB, 1/250), anti-laminin (polyclonal, Sigma, 1/200), anti-slow myosin (monoclonal, Sigma, 1/1000), anti Sox9 (R&D Systems, 1∶100) and anti-ß-Galactosidase (polyclonal, provided by Dr. J.-F Nicolas (France), 1/500). Secondary antibodies were coupled to fluorochromes: Alexa 488 (Molecular probes, 1/500) and Alexa 546 (Molecular probes, 1/1500). Images were obtained with an Apotome Zeiss microscope and Axiovision software at the Pasteur imaging center (PFID). All images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop.

Single Fiber Preparation and Regeneration Assays

Single fibers were prepared, cultured and processed for immunostaining as described previously [44]. After dissection, muscles were directly frozen in isopentane. Cryosections (10 microns) were processed for ß-Gal staining and immunostaining as described in [44]. Muscle injury using cardiotoxin injection and regeneration assays were performed, as described in [44].

Supporting Information

X-Gal staining of a Pax3Pax3-En/+ embryo at E10.75. A close-up view of the interlimb somitic region is shown in the right panel. X-Gal staining indicates that myogenic progenitor cells are still present in the presence of Pax3-Engrailed. (Pax3-En stands for Pax3-Engrailed-Ires-nlacZ).

(TIF)

Sections of the whole-mount in situ hybridization (ISH) shown in Figure 1 , panels G, H. The level of the section is indicated by a white bar and labeled A, B, C for interlimb, hindlimb and caudal level somites respectively. Left hand panels correspond to the wild-type embryo shown in G and right hand panels to the mutant shown in H. Itm2a is over-expressed in the presence of PAX3-FKHR.

(TIF)

A–B, Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe on control Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/+ ( Pax3Pax7/+ ) (A) and mutant Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/Splotch ( Pax3Pax7/Sp ) (B) embryos at E11.5. Pax3Sp is a naturally occuring mutant allele. C–D, X-Gal staining of control Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/+ (C) and mutant Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/Sp (B) embryos at E11.5. Close-ups of the interlimb somite region are shown. X-Gal staining indicates that myogenic progenitor cells (normally, Pax3+) are still present, although reduced in the limb buds where Pax3 plays a critical role in cell migration from the somite. Red arrows point to myogenic sites of Itm2a expression.

(TIF)

A–D’, Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe on Myf5nLacZ/+ (A, C, A’, C’) and Myf5nLacZ/nLacZ (B, D, B’, D’) embryos. A’–D’ show close-ups of the interlimb somite region. Embryonic stages are as indicated. Blue arrows point to Itm2a expression in the somites.

(TIF)

X-Gal staining of an E10.5 Itm2aXKO/Y male (A), Itm2aXKO/XKO (B) and Itm2aXKO/X (C) female embryos at E10.5. Note the chimeric X-Gal staining in the female embryo, due to random X inactivation in somatic cells.

(TIF)

Immunohistochemistry on transverse sections through forelimb buds of an Itm2aXcdKO/X; Pax3Cre/+ embryo at E10.5, using antibodies to ßGal (green) and the chondrocyte marker Sox9 (red). A, B,C: 20X, C is the merged image showing co-expression. A’, B, C’ : 63X of the region highlighted in A,B and C.

(TIF)

Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) for Itm2a transcripts in wild-type (A), heterozygote Itm2aXKO/X (B) and mutant Itm2aXKO/Y (C) embryos at E11.5. In B and C the mice were crossed with the PGK-Cre line to delete the floxed Itma2 allele. The signal in the head is propably a mixture of in situ hybridization background signal and some Itm2a expression in the most anterior region.

(TIF)

X-Gal staining of control Pax3GFP/GFP ; Itm2aXcdKO/Y (A) and Pax3GFP/GFP ; Itm2aKO/Y mutant (B) embryos at E10.5. The mice were crossed with the PGK-Cre line to delete the floxed Itma2 allele.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Bodin and Sabrina Coqueran for excellent technical help.

Funding Statement

This project was supported by funding to FR from the INSERM Avenir Program, Association Française Contre les Myopathies (AFM), Association Institut de Myologie, the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (LNCC), Association pour la Recherche Contre le Cancer (ARC), Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, Institut National du Cancer (INCa), and from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme in the project ENDOSTEM (grant agreement number 241440). MB’s laboratory was supported by the Pasteur Institute and the CNRS (URA 2578) and by grants from the AFM and the EU 7th PCRD programmes, EuroSyStem (grant agreement number 200720) and Optistem (grant agreement number 223098). ML is currently the recipient of a Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP) fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Buckingham M, Relaix F (2007) The Role of Pax Genes in the Development of Tissues and Organs: Pax3 and Pax7 Regulate Muscle Progenitor Cell Functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M (2005) A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature 435: 948–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang YX, Rudnicki MA (2011) Satellite cells, the engines of muscle repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. Buckingham M, Montarras D (2008) Skeletal muscle stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18: 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Mansouri A, Gruss P, et al. (2000) Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. Cell 102: 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Relaix F, Montarras D, Zaffran S, Gayraud-Morel B, Rocancourt D, et al. (2006) Pax3 and Pax7 have distinct and overlapping functions in adult muscle progenitor cells. J Cell Biol 172: 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins CA, Olsen I, Zammit PS, Heslop L, Petrie A, et al. (2005) Stem cell function, self-renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell 122: 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Montarras D, Morgan J, Collins C, Relaix F, Zaffran S, et al. (2005) Direct Isolation of Satellite Cells For Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Science 309: 2064–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Epstein JA, Shapiro DN, Cheng J, Lam PY, Maas RL (1996) Pax3 modulates expression of the c-Met receptor during limb muscle development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 4213–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bladt F, Riethmacher D, Isenmann S, Aguzzi A, Birchmeier C (1995) Essential role for the c-met receptor in the migration of myogenic precursor cells into the limb bud. Nature 376: 768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bajard L, Relaix F, Lagha M, Rocancourt D, Daubas P, et al. (2006) A novel genetic hierarchy functions during hypaxial myogenesis: Pax3 directly activates Myf5 in muscle progenitor cells in the limb. Genes Dev 20: 2450–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu P, Geles KG, Paik JH, DePinho RA, Tjian R (2008) Codependent activators direct myoblast-specific MyoD transcription. Dev Cell 15: 534–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M (2004) Divergent functions of murine Pax3 and Pax7 in limb muscle development. Genes Dev 18: 1088–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McKinnell IW, Ishibashi J, Le Grand F, Punch VG, Addicks GC, et al. (2008) Pax7 activates myogenic genes by recruitment of a histone methyltransferase complex. Nat Cell Biol 10: 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lagha M, Kormish JD, Rocancourt D, Manceau M, Epstein JA, et al. (2008) Pax3 regulation of FGF signaling affects the progression of embryonic progenitor cells into the myogenic program. Genes Dev 22: 1828–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mercado GE, Barr FG (2007) Fusions involving PAX and FOX genes in the molecular pathogenesis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: recent advances. Curr Mol Med 7: 47–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khan J, Bittner ML, Saal LH, Teichmann U, Azorsa DO, et al. (1999) cDNA microarrays detect activation of a myogenic transcription program by the PAX3-FKHR fusion oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 13264–13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mayanil CS, George D, Freilich L, Miljan EJ, Mania-Farnell B, et al. (2001) Microarray analysis detects novel Pax3 downstream target genes. J Biol Chem 276: 49299–49309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barber TD, Barber MC, Tomescu O, Barr FG, Ruben S, et al. (2002) Identification of target genes regulated by PAX3 and PAX3-FKHR in embryogenesis and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Genomics 79: 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao L, Yu Y, Bilke S, Walker RL, Mayeenuddin LH, et al. (2010) Genome-wide identification of PAX3-FKHR binding sites in rhabdomyosarcoma reveals candidate target genes important for development and cancer. Cancer Res 70: 6497–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Relaix F, Polimeni M, Rocancourt D, Ponzetto C, Schafer BW, et al. (2003) The transcriptional activator PAX3-FKHR rescues the defects of Pax3 mutant mice but induces a myogenic gain-of-function phenotype with ligand-independent activation of Met signaling in vivo. Genes Dev 17: 2950–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lagha M, Sato T, Regnault B, Cumano A, Zuniga A, et al. (2010) Transcriptome analyses based on genetic screens for Pax3 myogenic targets in the mouse embryo. BMC Genomics 11: 696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lagha M, Brunelli S, Messina G, Cumano A, Kume T, et al. (2009) Pax3:Foxc2 reciprocal repression in the somite modulates muscular versus vascular cell fate choice in multipotent progenitors. Dev Cell 17: 892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van den Plas D, Merregaert J (2004) Constitutive overexpression of the integral membrane protein Itm2A enhances myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. Cell Biol Int 28: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boeuf S, Borger M, Hennig T, Winter A, Kasten P, et al. (2009) Enhanced ITM2A expression inhibits chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Differentiation 78: 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Willander H, Hermansson E, Johansson J, Presto J (2011) BRICHOS domain associated with lung fibrosis, dementia and cancer–a chaperone that prevents amyloid fibril formation? FEBS J 278: 3893–3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanchez-Pulido L, Devos D, Valencia A (2002) BRICHOS: a conserved domain in proteins associated with dementia, respiratory distress and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci 27: 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mulugeta S, Maguire JA, Newitt JL, Russo SJ, Kotorashvili A, et al. (2007) Misfolded BRICHOS SP-C mutant proteins induce apoptosis via caspase-4- and cytochrome c-related mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cossu G, Kelly R, Tajbakhsh S, Di Donna S, Vivarelli E, et al. (1996) Activation of different myogenic pathways: myf-5 is induced by the neural tube and MyoD by the dorsal ectoderm in mouse paraxial mesoderm. Development 122: 429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kassar-Duchossoy L, Gayraud-Morel B, Gomes D, Rocancourt D, Buckingham M, et al. (2004) Mrf4 determines skeletal muscle identity in Myf5:Myod double-mutant mice. Nature 431: 466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, Cossu G, Buckingham M (1997) Redefining the genetic hierarchies controlling skeletal myogenesis: Pax-3 and Myf-5 act upstream of MyoD. Cell 89: 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Soleimani VD, Punch VG, Kawabe Y, Jones AE, Palidwor GA, et al. (2012) Transcriptional dominance of Pax7 in adult myogenesis is due to high-affinity recognition of homeodomain motifs. Dev Cell 22: 1208–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clerc P, Avner P (2006) Random X-chromosome inactivation: skewing lessons for mice and men. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16: 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rizzoti K, Brunelli S, Carmignac D, Thomas PQ, Robinson IC, et al. (2004) SOX3 is required during the formation of the hypothalamo-pituitary axis. Nat Genet 36: 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Deleersnijder W, Hong G, Cortvrindt R, Poirier C, Tylzanowski P, et al. (1996) Isolation of markers for chondro-osteogenic differentiation using cDNA library subtraction. Molecular cloning and characterization of a gene belonging to a novel multigene family of integral membrane proteins. J Biol Chem 271: 19475–19482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kirchner J, Bevan MJ (1999) ITM2A is induced during thymocyte selection and T cell activation and causes downregulation of CD8 when overexpressed in CD4(+)CD8(+) double positive thymocytes. J Exp Med 190: 217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tuckermann JP, Pittois K, Partridge NC, Merregaert J, Angel P (2000) Collagenase-3 (MMP-13) and integral membrane protein 2a (Itm2a) are marker genes of chondrogenic/osteoblastic cells in bone formation: sequential temporal, and spatial expression of Itm2a, alkaline phosphatase, MMP-13, and osteocalcin in the mouse. J Bone Miner Res 15: 1257–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vincent SD, Buckingham ME (2010) How to make a heart: the origin and regulation of cardiac progenitor cells. Curr Top Dev Biol 90: 1–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lallemand Y, Luria V, Haffner-Krausz R, Lonai P (1998) Maternally expressed PGK-Cre transgene as a tool for early and uniform activation of the Cre site-specific recombinase. Transgenic Res 7: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Engleka KA, Gitler AD, Zhang M, Zhou DD, High FA, et al. (2005) Insertion of Cre into the Pax3 locus creates a new allele of Splotch and identifies unexpected Pax3 derivatives. Dev Biol 280: 396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown CB, Wenning JM, Lu MM, Epstein DJ, Meyers EN, et al. (2004) Cre-mediated excision of Fgf8 in the Tbx1 expression domain reveals a critical role for Fgf8 in cardiovascular development in the mouse. Dev Biol 267: 190–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zammit PS, Golding JP, Nagata Y, Hudon V, Partridge TA, et al. (2004) Muscle satellite cells adopt divergent fates: a mechanism for self-renewal? J Cell Biol 166: 347–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chang TH, Primig M, Hadchouel J, Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, et al. (2004) An enhancer directs differential expression of the linked Mrf4 and Myf5 myogenic regulatory genes in the mouse. Dev Biol 269: 595–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pallafacchina G, Francois S, Regnault B, Czarny B, Dive V, et al. (2010) An adult tissue-specific stem cell in its niche: a gene profiling analysis of in vivo quiescent and activated muscle satellite cells. Stem Cell Res 4: 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckingham M, Montarras D (2008) Skeletal muscle stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46. Pittois K, Wauters J, Bossuyt P, Deleersnijder W, Merregaert J (1999) Genomic organization and chromosomal localization of the Itm2a gene. Mamm Genome 10: 54–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fleischer A, Ayllon V, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, Rebollo A (2002) Proapoptotic activity of ITM2B(s), a BH3-only protein induced upon IL-2-deprivation which interacts with Bcl-2. Oncogene 21: 3181–3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

X-Gal staining of a Pax3Pax3-En/+ embryo at E10.75. A close-up view of the interlimb somitic region is shown in the right panel. X-Gal staining indicates that myogenic progenitor cells are still present in the presence of Pax3-Engrailed. (Pax3-En stands for Pax3-Engrailed-Ires-nlacZ).

(TIF)

Sections of the whole-mount in situ hybridization (ISH) shown in Figure 1 , panels G, H. The level of the section is indicated by a white bar and labeled A, B, C for interlimb, hindlimb and caudal level somites respectively. Left hand panels correspond to the wild-type embryo shown in G and right hand panels to the mutant shown in H. Itm2a is over-expressed in the presence of PAX3-FKHR.

(TIF)

A–B, Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe on control Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/+ ( Pax3Pax7/+ ) (A) and mutant Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/Splotch ( Pax3Pax7/Sp ) (B) embryos at E11.5. Pax3Sp is a naturally occuring mutant allele. C–D, X-Gal staining of control Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/+ (C) and mutant Pax3Pax7-IRESnLacZ/Sp (B) embryos at E11.5. Close-ups of the interlimb somite region are shown. X-Gal staining indicates that myogenic progenitor cells (normally, Pax3+) are still present, although reduced in the limb buds where Pax3 plays a critical role in cell migration from the somite. Red arrows point to myogenic sites of Itm2a expression.

(TIF)

A–D’, Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) with an Itm2a antisense riboprobe on Myf5nLacZ/+ (A, C, A’, C’) and Myf5nLacZ/nLacZ (B, D, B’, D’) embryos. A’–D’ show close-ups of the interlimb somite region. Embryonic stages are as indicated. Blue arrows point to Itm2a expression in the somites.

(TIF)

X-Gal staining of an E10.5 Itm2aXKO/Y male (A), Itm2aXKO/XKO (B) and Itm2aXKO/X (C) female embryos at E10.5. Note the chimeric X-Gal staining in the female embryo, due to random X inactivation in somatic cells.

(TIF)

Immunohistochemistry on transverse sections through forelimb buds of an Itm2aXcdKO/X; Pax3Cre/+ embryo at E10.5, using antibodies to ßGal (green) and the chondrocyte marker Sox9 (red). A, B,C: 20X, C is the merged image showing co-expression. A’, B, C’ : 63X of the region highlighted in A,B and C.

(TIF)

Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) for Itm2a transcripts in wild-type (A), heterozygote Itm2aXKO/X (B) and mutant Itm2aXKO/Y (C) embryos at E11.5. In B and C the mice were crossed with the PGK-Cre line to delete the floxed Itma2 allele. The signal in the head is propably a mixture of in situ hybridization background signal and some Itm2a expression in the most anterior region.

(TIF)

X-Gal staining of control Pax3GFP/GFP ; Itm2aXcdKO/Y (A) and Pax3GFP/GFP ; Itm2aKO/Y mutant (B) embryos at E10.5. The mice were crossed with the PGK-Cre line to delete the floxed Itma2 allele.

(TIF)