Abstract

This study examined change in self-efficacy as a mediator of the effects of a mailed print intervention on the dietary and exercise practices of newly diagnosed breast and prostate cancer survivors (N = 519). Results indicated that changes in self-efficacy for fat restriction and eating more fruits and vegetables were significant mediators of the intervention’s effects on dietary outcomes at 1-year follow-up. The intervention did not significantly affect self-efficacy for exercise; however, a significant, positive relationship was found between self-efficacy for exercise and exercise duration at follow-up. Findings are largely consistent with Social Cognitive Theory and support the use of strategies to increase self-efficacy in health promotion interventions for cancer survivors.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, survivors, diet, exercise, randomized controlled trial

As advances in early detection and treatment have been incorporated into clinical practice, the number of cancer survivors has steadily increased [1]. Current estimates indicate that there are over 10 million cancer survivors in the United States alone, representing between 3% and 4% of the United States population [2]. The proportion of cancer survivors is expected to grow as a result of trends toward aging and continued progress in cancer screening and care [2–6].

Although the rapid increase in cancer survivors is encouraging, the long-term health effects of cancer and its treatment are becoming a public health concern. Data indicate that compared to persons without a history of cancer, cancer survivors are at greater risk for developing secondary cancers and other diseases or conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, and functional decline [2–8]. Reasons for increased risk across conditions may include cancer treatment-related sequelae, genetic predisposition, or lifestyle factors [9].

Unhealthy lifestyle practices, including physical inactivity, suboptimal fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption, and high intakes of fat, have been associated with increased risk of several types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic diseases [9–12]. Conversely, recent data suggest that exercise may reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and mortality among individuals with a history of colorectal cancer or breast cancer [13–15]. In addition, research indicates that a low-fat diet may reduce cancer recurrence in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors [16]. Unfortunately, survey results suggest that a large proportion of cancer survivors do not adhere to national guidelines regarding exercise and diet [1, 17]. Indeed, recent data derived from national samples reveal few lifestyle differences between individuals diagnosed with cancer and healthy populations or noncancer control participants [1, 17].

In an effort to improve the lifestyle practices of cancer survivors, more than 40 diet and exercise interventions have been conducted with this population [18, 19]. Most of the studies have yielded promising results, with exercise interventions showing enhanced cardiorespiratory fitness and quality of life and decreased fatigue, and dietary interventions showing lower body weight and increases in dietary biomarkers [18, 20–24]. Recently, Demark-Wahnefried and colleagues [25] examined the effects of a diet and exercise intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors throughout North America. This randomized trial, entitled FRESH START, is the first diet and exercise intervention for cancer survivors delivered exclusively via mailed printed materials. Both an attention control group who received standardized materials regarding diet and exercise and an intervention group who received materials that were tailored to their demographic and psychological characteristics and progress toward goal attainment showed gains in specific lifestyle behavior (i.e., increased exercise and F&V intake and reduced fat intake), as well as improvement in diet quality (a global construct that reflects the overall nature of the dietary pattern and compares it to defined food patterns associated with lower risk of morbidity and mortality that are characterized by higher intakes of F&V, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, and lean meat sources) [26–28]. The intervention group achieved significantly greater improvement across all outcome variables, with the exception of general quality of life.

The FRESH START intervention was based on Social Cognitive Theory in which the core determinants of health behavior include knowledge of the risks and benefits of the behavior, perceived self-efficacy (i.e., self-confidence that one can engage in health behaviors under various circumstances), outcome expectations, health goals, and strategies for achieving these goals [29, 30]. From a social cognitive perspective, self-efficacy plays a central role in behavior change by directly affecting health behavior and by influencing all other determinants [29, 30]. Bandura [30] theorized that people with high levels of self-efficacy set high goals for themselves, expect to attain favorable outcomes, and persevere in the face of adversity. The FRESH START intervention was designed to influence self-efficacy and associated variables by emphasizing the benefits of practicing the goal behavior, detailing incremental tasks toward the goal with a focus on overcoming self-reported barriers, and providing encouragement to achieve the goal [25].

While several dietary trials have utilized Social Cognitive Theory and have reported data on self-efficacy [31–33], few studies have formally evaluated change in self-efficacy as a potential mediator, despite calls for exploration of mediating factors in health promotion interventions [34]. Evidence suggests that self-efficacy is an important mediator in interventions designed to increase adults’ F&V intake [31–33]. Although many studies have found a positive correlation between self-efficacy and physical activity [35], exercise intervention studies with self-efficacy as a potential mediator have yielded mixed results [36–39]. For example, one study found that self-efficacy mediated an intervention’s effects on physical activity among mothers [38], whereas another study conducted in a primary care setting did not find support for self-efficacy as a mediator [39].

Researchers have begun to explore the role of self-efficacy in exercise interventions for cancer survivors, most of which have been conducted among breast cancer survivors [40, 41]. The present study extended prior work by examining change in self-efficacy as a potential mediator of the effects of a diet and exercise intervention among both breast and prostate cancer survivors. Based on Social Cognitive Theory [29, 30] and previous research [31–33], we hypothesized that change in self-efficacy for dietary fat restriction and eating more F&V would partially mediate the intervention’s effects on diet quality. We also hypothesized that change in self-efficacy for eating more F&V would partially mediate the intervention’s effects on daily servings of F&V, and change in self-efficacy for fat restriction would partially mediate the intervention’s effects on the percentage of kcal from fat. Finally, we predicted that change in self-efficacy for exercise would partially mediate the intervention’s effects on total minutes of exercise per week.

Method

Participants

A total of 306 breast cancer patients and 237 prostate cancer patients who had been diagnosed with early stage (in situ, localized, or regional) cancer within the previous 9 months participated in the randomized trial. Patients were excluded from the study if they had conditions precluding unsupervised exercise (uncontrolled congestive heart failure or angina, recent myocardial infarction, or breathing difficulties requiring oxygen use or hospitalization; walker or wheelchair use; or plans to have hip or knee replacement) or if they had conditions precluding a high F&V diet (kidney failure or chronic warfarin use). Individuals with progressive cancer or additional primary tumors or those unable to read and write in English also were excluded.

The present research examines data from participants (n = 519) who completed the one-year follow-up assessment. Participants were primarily Caucasian (83%) or African American (13%) and well-educated (88% with at least some college). The average age of participants was 57.0 years (SD 10.8) and the average time since diagnosis was 3.83 months (SD 2.74) at the point of study recruitment. Most participants (85%) had undergone surgery and received cancer therapies, including radiation (45%), chemotherapy (27%), and hormonal therapy (39%).

Procedure

Participants were recruited via cancer registries of participating medical centers, self-referral, or large oncology practices in 39 states and 2 provinces in North America. This study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Complete descriptions of the sample and intervention conditions and statistical analyses of the accrual procedures have been previously reported [25, 42–44]. To briefly summarize, we found significant differences (p-values < .001) between participants versus nonparticipants on age (58 vs. 62 years, respectively), race (19% vs. 38% minority, respectively), and gender (54% vs. 46% female, respectively). Study arms (FRESH START intervention vs. attention control) did not differ with respect to age, race, gender, education, type and clinical stage of cancer, and cancer-related treatment.

Potential participants (n = 678) who were at least 6 months post-diagnosis completed the baseline screening following receipt of primary therapy. Individuals were subsequently excluded from randomization to one of the two study arms if they practiced two or more goal behaviors (exercised 150+ min/wk or adhered to a low-fat or high-F&V diet). Participants in both study arms (n = 543) received a 10-month intervention that aimed to improve diet and exercise behaviors. The intervention involved an initial workbook followed by a series of seven tailored newsletters at 6-week intervals. Specifically, mailings were tailored to the experimental participants’ demographic characteristics [25], cancer coping style [45], stage of readiness, barriers to lifestyle changes, and progress toward goal attainment of exercising 150+ min/wk, eating five or more servings of F&V per day, or limiting total and saturated fat intakes to less than 30% and 10% of kcal, respectively [42]. Newsletters included a testimonial tailored on age (i.e., < 60 vs. ≥ 60 years old), race (i.e., African American or other), and cancer coping style (e.g., “fighting spirit,” “fatalist”) derived from a modified version of the Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer subscale administered at baseline [45]. These testimonials were provided as a “role model” to enhance observational learning. Messages also were tailored to the participants’ reported barriers to the goal behavior (e.g., lack of time, expense) as a means of offering useful strategies to engage in healthful behaviors and improve confidence. Each newsletter also included a graph indicating the participant’s progress in relation to the goal and tailored messages of encouragement and/or praise regarding goal attainment. Finally, newsletters were tailored on stage of readiness [i.e., precontemplation (not thinking about change), contemplation (thinking about change), and preparation/action (beginning to take or taking active steps toward change)] strictly as a means of enhancing engagement [46]. In addition, non-tailored sections of the newsletter addressed benefits of lifestyle change to increase expectancy of a positive conditional outcome. Each experimental participant received two 5-month mailings on F&V consumption, dietary fat restriction, or exercise, and only received materials in areas where they did not meet the goal behavior. Participants who did not practice any goal behaviors at baseline were randomly assigned to two of the three 5-month mailings.

Control participants received a workbook that included the “Facing Forward” booklet (National Cancer Institute) and six subsequent mailings of publically available materials on healthy dietary practices (i.e., F&V consumption and dietary fat restriction) and exercise on a similar schedule to those in the FRESH START intervention arm [42]. For example, control participants received the “Just Move” brochure (American Heart Association) and the “Action Guide for Healthy Eating” brochure (National Institute of Health); a complete listing of brochures is provided in a previously published methods paper [42]. Current smokers in both arms received the American Lung Association “Quitting for Life” brochure (2003PS96328).

Between mailings, participants in both study arms received brief surveys and were offered $5 for each returned survey. The surveys for control participants assessed the perceived helpfulness of the brochures, whereas the surveys for experimental participants assessed current health practices and readiness to pursue lifestyle changes. This information was used to individually tailor the workbook and newsletters, such that experimental participants received continually updated feedback.

Computer-assisted telephone interviews of 45 to 55 minutes each were conducted with participants at baseline and at a one-year follow-up. Of the 543 patients enrolled in the intervention trial, 4 patients (0.7%) had died or become ill and 20 patients (3.7%) had dropped out of the study, resulting in a follow-up sample of 519 participants. Attrition did not differ by race, sex, or educational status; however, the experimental arm had a significantly higher attrition rate than the control arm (6.6% vs. 2.2%, respectively, p = .01).

Measures

Dietary outcomes

Participants completed the Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) [47, 48], which was modified to include regionally consumed foods (e.g., hominy, okra). Research has supported the reliability and validity of this questionnaire, which assesses fat intake, as well as consumption of many other foods and nutrients, over the past 12 months [47, 48]. Outcome variables for the present research included the number of servings of F&V per day, the percentage of kcal from fat, and the Diet Quality Index-Revised score [49], with higher numbers indicating better diet quality.

Exercise

Exercise was assessed using the 7-day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) [50–52]. This measure has been validated and used in several large-scale studies [50, 51]. Total minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity was an outcome variable for the present research.

Self-Efficacy

For each of the goal behaviors, participants rated their self-efficacy in response to the question, “How sure are you that you could (exercise at least 30 minutes a day at least 5 days a week; eat at least 5 servings of F&V per day; or eat a low-fat diet)?” The questions and rating scales were developed jointly by the 5-a-Day community research projects and the NCI [53, 54] and have been tested with ethnically diverse samples, including African Americans in the Black Churches United for Better Health project [55]. Participants responded to each question on a 5-point scale from 1 (very unsure) to 5 (very sure). Descriptions of exercise, F&V servings, and a low-fat diet were provided prior to each question (e.g., exercise: “Examples of exercise are brisk walking, cycling, swimming, weight lifting, or other activities that get your heart pounding or have you break out in a sweat and are NOT part of your normal activity on the job”).

Data Analysis

We used multiple regression analyses to test for mediation, using the procedures set forth by Baron and Kenny [56]. Four conditions must be met to establish mediation. First, the independent variable (i.e., intervention condition) must be significantly associated with the dependent variable. Second, the intervention must significantly affect the putative mediator (i.e., self-efficacy). To examine the third step in mediation, we tested whether change in self-efficacy was related to change in the dependent variable in a model controlling for the effects of the intervention condition. If the effect of self-efficacy is significant and the effect of intervention condition is reduced or eliminated, we have evidence for statistical mediation. The final step is to test the statistical significance of the mediated effect.

As suggested by Shrout and Bolger [57], a bootstrap procedure was used to evaluate the significance of the indirect effect of intervention condition on outcome variables via self-efficacy. In general, bootstrap methods offer an empirical approach to examining the significance of statistical estimates [58] and has improved statistical power relative to other methods for testing the magnitude and significance of mediation effects [59]. We used a macro developed by Preacher and Hayes [60] that creates 5,000 samples from the data set by sampling with replacement in order to compute the indirect effect in each sample. The bootstrap estimate of the indirect effect is the mean indirect effect over the 5,000 samples. Shrout and Bolger [57] recommended that researchers report the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the significance of mean indirect effects from the bootstrap results. If the CI does not include zero, then the indirect effect is considered statistically significant at the .05 level. We report bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals, which have shown better performance under a variety of assumptions than percentile confidence intervals [61, 62].

In the analysis regarding diet quality, all experimental participants (n = 253) were included because each participant received at least one dietary intervention component (i.e., material to encourage F&V intake, reduce fat intake, or both). When examining specific health behaviors, only experimental participants who had received materials that targeted the percentage of kcal from fat (n = 204), servings of F&V (n = 116), and exercise (n = 186) were included in each analysis. Control participants were included in all analyses because they received materials that targeted all three health behaviors (i.e., fat reduction, F&V consumption, and exercise). Baseline values of the mediator and dependent variables were included as covariates in all analyses; thus, the effects observed represent change over the course of the intervention. Demographic and medical variables were not included as covariates because no significant differences emerged on these variables as a function of intervention condition at baseline.

Several potential mediators and moderators of the intervention’s effects were examined and excluded from the final analyses. Gender, a variable confounded with cancer type, and age did not significantly interact with self-efficacy to predict outcomes (data not shown). In addition, changes in the number of barriers to F&V consumption, fat reduction, and exercise from baseline to follow-up were analyzed as potential mediators of the intervention’s effects on outcome variables. However, intervention condition did not predict changes in the number of barriers (data not shown).

Results

Effects of Intervention Condition, Gender, and Age on Outcome Variables

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and comparisons of mean scores at follow-up for study variables. Similar data were reported by Demark-Wahnefried and colleagues [25]; however, the data presented for the current study exclude the 24 people for whom follow-up data were missing. As in the full sample, the main effect of experimental condition was significant for exercise and dietary outcomes at one year. Consistent with hypotheses, patients who received the FRESH START intervention differed significantly from the attention control group in that they reported greater exercise and F&V intake, fewer calories from fat, and better diet quality at the 1-year follow-up assessment. Self-efficacy for fat restriction and F&V intake also was higher for intervention participants relative to control participants at follow-up. However, self-efficacy for exercise did not differ as a function of group assignment.

Table 1.

Study Variables at Baseline and 1-Year Follow-up as a Function of Group Assignment

| FRESH START Intervention (n = 253) | Attention Control (n = 266) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline | 1-Year Follow-up | Baseline | 1-Year Follow-up | p | |

| Diet Quality Index-Revised score | 66.5 (11.3) | 72.8 (10.6) | 66.9 (9.5) | 68.7 (10.9) | <.001 |

| Total percent of calories from fat | 38.0 (5.7) | 33.7 (5.7) | 37.8 (5.6) | 35.7 (4.6) | <.001 |

| No. of daily servings of F&V | 5.1 (2.7) | 6.2 (2.8) | 5.0 (2.3) | 5.6 (2.6) | <.05 |

| Exercise, min/wk | 53.0 (112.9) | 112.7 (126.6) | 44.7 (89.5) | 83.8 (119.1) | <.01 |

| Self-efficacy for fat restriction | 3.9 (.9) | 4.1 (.9) | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.9 (1.0) | <.01 |

| Self-efficacy for eating more F&V | 3.9 (.9) | 4.2 (.9) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.0 (1.0) | <.05 |

| Self-efficacy for exercise | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.2) | .07 |

Note. Standard deviations are in parentheses. P values are presented for group comparisons at follow-up. F&V = fruits and vegetables.

Gender was unrelated to the dependent variables, except that men reported greater exercise at baseline relative to women, t(517) = −5.51, p < .001. Men also reported greater self-efficacy for exercise than women at baseline, t(517) = −3.21, p < .01, and follow-up, t(517) = −2.16, p < .05. However, women reported greater self-efficacy for fat reduction, t(517) = 2.57, p < .05, and F&V consumption, t(517) = 2.09, p < .05, relative to men at follow-up. Age was not associated with self-efficacy variables, exercise, or the percentage of kcal from fat, but was positively associated with diet quality and F&V consumption at baseline (r = .19, p < .001; r = .15, p < .001) and follow-up (r = .19, p < .001; r = .13, p < .01), respectively.

Self-efficacy as a Mediator of Intervention Condition on Outcome Variables

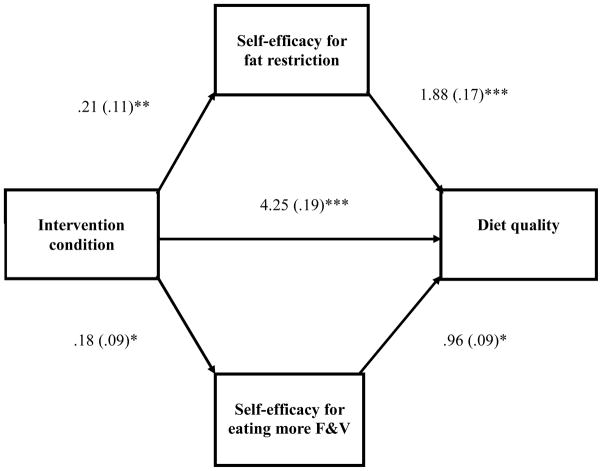

The first analysis evaluated the hypothesis that changes in self-efficacy for fat restriction and self-efficacy for eating more F&V would mediate the association between the intervention and diet quality (see Figure 1). The entire model accounted for 37.7% of the variance in diet quality, F(6, 512) = 51.68, p < .001, and the effect of the intervention was attenuated by the mediators (β = .19, p < .001, without mediators vs. β = .17, p < .001, with mediators). Partial mediation was suggested when examining changes in self-efficacy for fat restriction (mean indirect effect = .02, SE = .01, 95% CI = .0052 to .0399) and self-efficacy for eating more F&V (mean indirect effect = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI = .0003 to .0231). Experimental participants endorsed greater changes in self-efficacy for fat restriction and eating more F&V than did control participants, which, in turn, were associated with better diet quality.

Figure 1.

Model depicting the effects of intervention condition (coded 0 = attention control, 1 = FRESH START intervention) on diet quality and mediators, adjusting for baseline mediator and dependent variables. Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown outside of the parentheses, and standardized coefficients are reported in the parentheses. F&V = fruits and vegetables.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

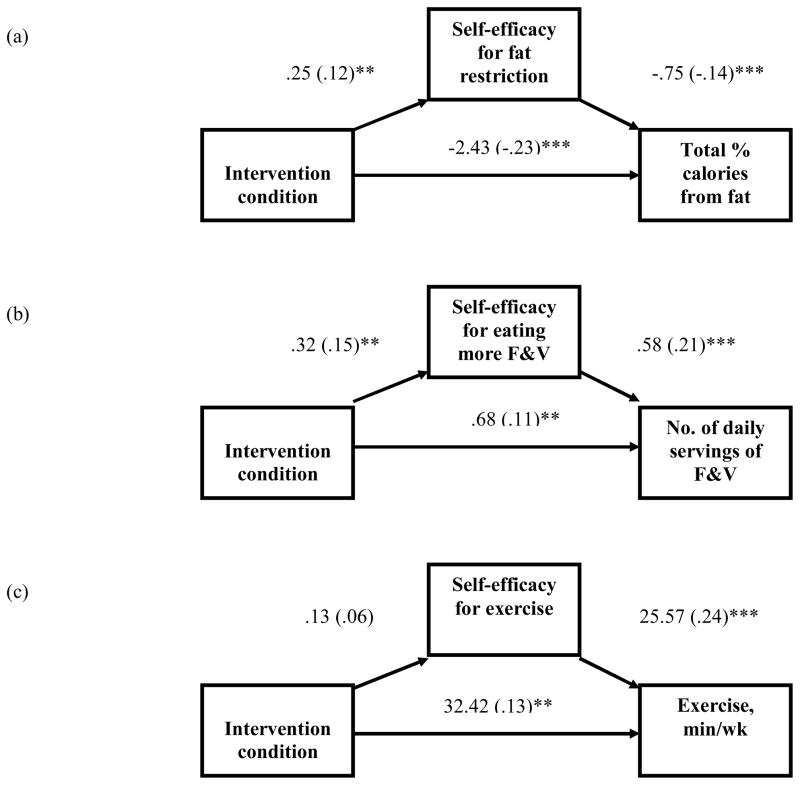

Next, we tested the hypothesis that change in self-efficacy for fat restriction would mediate the association between intervention condition and the percentage of kcal from fat (see Figure 2a). This model accounted for 30.1% of the variance in the percentage of kcal from fat, F(4, 465) = 49.95, p < .001. The effect of the intervention was attenuated by the mediator (β = −.23, p < .001, without mediator vs. β = −.21, p < .001, with mediator), and partial mediation was suggested (mean indirect effect = −.02, SE = .01, 95% CI = −.0363 to −.0064). Experimental participants endorsed greater change in self-efficacy for fat restriction than did control participants, which, in turn, was associated with a lower percentage of kcal from fat. We then tested the prediction that change in self-efficacy for eating more F&V would mediate the association between intervention condition and daily servings of F&V (see Figure 2b). This model accounted for 44.6% of the variance in daily servings of F&V, F(4, 377) = 75.83, p < .001. The effect of the intervention was attenuated by the mediator (β = .11, p < .01, without mediator vs. β = .08, p < .05, with mediator), and partial mediation was suggested (mean indirect effect = .03, SE = .01, 95% CI = .0113 to .0588). Experimental participants reported greater change in self-efficacy for eating more F&V than did control participants, which, in turn, was associated with more daily servings of F&V. Finally, results did not support the hypothesis that change in self-efficacy for exercise would mediate the association between intervention condition and total minutes of exercise per week (see Figure 2c). Intervention condition was not significantly associated with self-efficacy for exercise; however, a significant, positive relationship was found between self-efficacy for exercise and total minutes of exercise per week at follow-up.

Figure 2.

Figures 2a–c. Model depicting the effects of intervention condition (coded 0 = attention control, 1 = FRESH START intervention) on exercise and dietary outcomes and mediators, adjusting for baseline mediator and dependent variables. Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown outside of the parentheses, and standardized coefficients are reported in the parentheses. F&V = fruits and vegetables.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study examines change in self-efficacy as a potential mediator of the positive health behavior changes produced by FRESH START, a diet and exercise intervention for cancer survivors [25]. Results support the hypothesis that changes in self-efficacy for fat restriction and eating more F&V partially mediate the effects of the intervention on diet quality. Furthermore, change in self-efficacy for fat restriction partially mediated the intervention’s effects on the percentage of kcal from fat, and change in self-efficacy for F&V consumption partially mediated the intervention’s effects on daily servings of F&V. These findings extend those of other intervention studies that found support for a mediated effect of behavior-specific self-efficacy on adults’ F&V consumption [31, 33]. In addition, results are consistent with Social Cognitive Theory which posits that an individual’s confidence in his or her ability to engage in behavior predicts health behavior change [29, 30]. The methods of the FRESH START intervention trial (e.g., encouraging participants to set incremental goals, reinforcing efforts toward goal attainment) were designed to promote self-efficacy, and, indeed, participants reported improved self-efficacy for dietary practices at follow-up. Thus, our results in combination with prior research [31–33] suggest that continued emphasis on self-efficacy in dietary intervention studies is warranted. Indeed, the magnitude of the change and differences observed between arms in this study surpass that seen in other trials in the general population [55], which may be a reflection of increased motivation to pursue lifestyle change among newly diagnosed cancer survivors [18]. While it could be argued that changes in fat or F&V consumption may not necessarily have a clinically meaningful impact on cancer-specific outcomes, especially in light of recent findings from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study [63], it must be remembered that survivors are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease for which these modifications have proven benefit [64–66].

Contrary to our hypothesis, change in self-efficacy for exercise did not mediate the intervention’s effects on total minutes of exercise per week. Although intervention condition was not significantly associated with self-efficacy for exercise, a positive correlation between self-efficacy for exercise and total minutes of exercise per week was obtained. The latter finding is consistent with other studies that have found positive associations between self-efficacy and physical activity [35, 67]. The extent to which exercise interventions were associated with increased self-efficacy has varied across time points [39] and gender [68], and formal tests of self-efficacy as a potential mediator have yielded mixed findings [36–39]. In this study, levels of self-efficacy were fairly high at baseline, which left little room for positive change during the intervention period. The consistency of the association between self-efficacy and exercise adherence [35] and the success of the current exercise intervention and others that were based on Social Cognitive Theory [36, 37, 69–71] suggest that self-efficacy for exercise deserves further empirical attention.

The present study is noteworthy, given the limited number of studies examining the importance of psychosocial mediators in diet and exercise intervention trials. One strength is that formal tests of mediation [56] were conducted with past behavior and beliefs as covariates. The attention control group served as a rigorous comparison group, and the exceptionally low attrition rate (4.4%) enhances confidence in the findings. The present analysis extends prior work since multiple health behaviors were targeted via a mailed print intervention. In contrast, most trials have examined hospital-based programs that focus on one health behavior. Finally, this intervention study is unique in that we accrued a large sample of breast and prostate cancer survivors throughout North America, whereas most trials have targeted only breast cancer survivors at one institution.

This planned exploratory secondary analysis is limited in that we did not include other social-cognitive constructs that may influence physical activity behavior change (e.g., social support, self-regulatory strategies, facilitators, and outcome expectations). Subsequent experimental investigations should examine the contribution of these constructs and self-efficacy to behavior change by prospectively evaluating intervention components [72]. Another potential limitation is that we relied on 1-item measures of behavioral self-efficacy (self-efficacy for exercise, fat restriction, and eating more F&V). Although this method is common in practice to reduce participant burden, it may not be optimal. The use of a multi-item scale of self-efficacy in future trials would further validate these findings and may provide a better estimate of the magnitude of the mediated effect. This study also relied on self-report measures of diet and exercise. Although self-reported dietary data were strongly supported by objective data (e.g., plasma alpha-carotene) from a 23% subsample [25], imprecision and the possibility of response biases are inherent limitations of self-reported measurement techniques. Finally, the lower proportion of ethnic minorities, older adults, and individuals of lower educational attainment in this study relative to the general population should be noted. While this study relied on a more diverse sample than many other lifestyle intervention trials conducted among cancer survivors [19], further research is needed to examine potential mechanisms underlying effects of similar interventions in samples that are entirely representative of the population at large.

Despite limitations, results suggest that dietary interventions for cancer survivors should focus on increasing self-efficacy for engaging in healthy eating habits. Self-efficacy may be enhanced as participants are encouraged to set realistic goals and are reinforced for efforts toward goal attainment. Identifying important psychosocial mediators in intervention trials would allow for the development of low-cost, highly effective interventions that promote adherence to lifestyle guidelines among the growing population of cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

FRESH START is supported by the National Institutes of Health through the following grants: CA81191, CA74000, CA63782, and M01-RR-30. The work of the first author is supported by the National Cancer Institute through the following grant: 1F32CA130600-01. The authors wish to thank Drs. Colleen McBride and Bercedis Peterson, other co-investigators on this trial, as well as to acknowledge the memory of Dr. Elizabeth Clipp. We also wish to thank Drs. Marci Campbell, Harvey Cohen, Bethany Jackson, P. Kelly Marcom, Bess Marcus, and Thomas Polascik for their guidance in areas of design and implementation, and Drs. Walter Ettinger, Frank Harrell, and Thomas Scott for serving on our external data safety and monitoring board. We are grateful for the contributions and professionalism demonstrated by the staff of People Designs, Inc. (David Farrell, MPH, Jetze Beers, Marley Beers, MFA, and Kristin Trangsrud, MPH) who helped craft the FRESH START intervention materials, and Dr. Cecelia and Len Doak of Patient Learning Associates, Inc. who helped make them easily understandable. The authors also wish to thank the following individuals who have and are continuing to contribute expertise and support: Sreenivas Algoti, MS, Teresa Baker, Rita Freeman, Sonya Goode Green, MPH, Heather MacDonald, Barbara Parker, Shelley Rusincovitch, Rachel Schanberg, MS, and Russell Ward. We also are grateful to our participating institutions (Duke University Medical Center, Durham Regional Hospital, Durham VA Medical Center, Maria Parham Hospital, Raleigh Community Hospital, and Rex Healthcare), cancer registrars/patient care coordinators (Renee Gooch, Blanche Sellars, Dortch Smith, Donna Thompson, and Cheri Willard), and participating physicians (Drs. Victor E. Abraham, Anjana Acharya, David Albala, Alex Althausen, Everett Anderson, Roger F. Anderson, Mitchell Anscher, Guillermo Arana, Carlos Arcangelli, Sucha Asbell, Michael Aspera, James N. Atkins, Cheryl Aylesworth, Margaret Barnes, Brian Bauer, Louis Baumann, Michael Beall, Gregory Bebb, Michael Beecher, John Bell, Marc Benevides, Brian C. Bennett, Robert Bennett, Robert Bennion, James Benton, Stuart Bergman, William R. Berry, Kelly Blair, Kimberly Blackwell, Gayle Blouin, Peter Blumencranz, William Bobbitt, Daniel Borison, William Bouchelle, Elaine Bouttell, Don Boychuk, Barb Boyer, Albert Brady, Thomas Brammer, Scott Brantley, Joanna Brell, Charles Brendler, Thomas Brennan, Donald Brennan, Elizabeth Brew, Thomas Bright, Philip Brodak, Dieter Bruno, Dale Bryansmith, Niall Buckley, Walter W. Burns, W. Woodrow Burns, Thomas Buroker, Barbara Burtness, Amanullah Buzdar, David Caldwell, Elizabeth E. Campbell, Susan Campos, Sean Canale, Woodward Cannon, Dominick Carbone, Albert Casazza, George Case, Michael Cashdollar, Stanton Champion, Nitin Chandramouli, Marie Chenn, S. Chew, Stephen Chia, Warren Chin, Richard Chiulli, Elaine Chottiner, Walter Chow, Peter Clark, Kenneth Collins, Barry Conway, Suzanne Conzen, David Cook, John Corman, Shawn Cotton, D. Scott Covington, Edwin B. Cox, Frank Critz, Nancy J. Crowley, Sam Currin, Brian Czernieki, Brian Czito, Bruce Dalkin, John T. Daniel, John Danneberger, Leroy Darkes, Glenn Davis, Walter E. Davis, Jean de Kernion, Pat DeFusco, Fletcher Derrick, Margaret Deutsch, Gayle Dilalla, Robert Diloreto, Craig Donatucci, Michael Donovan, John Doster, Bradford Drury, Paul Dudrick, William Dunlap, Edward Eigner, Maha Elkordy, Matthew Ellis, Richard Evans, Jerry Fain, Anne Favret, Ira Fenton, Dirk Fisher, James Foster, Wyatt Fowler, Jeffrey Freeland, Daniel Frenning, Ralf Freter, Michael Frontiera, Michele Gadd, Anthony Galanos, Ronald Garcia, Antonio Gargurevich, Helen Garson, Morris Geffen, Gregory Georgiade, Ward Gillett, Paul Gilman, Jeffrey Gingrich, Deborah Glassman, John Gockerman, Richard Goodjoin, J. Phillip Goodson, Joel Goodwin, Teong Gooi, Jeffrey Gordon, Narender Gorukanit, James Gottesman, Lav Goyal, William Graber, Margaret Gradison, Gordon Grado, Mark Graham, Michael Grant, Stephen Greco, Carl Greene, Peter Grimm, Nima Grissom, Irina Gurevich, Carol Hahn, Alex Haick, Craig Hall, Edward Halperin, Sabah Hamad, R. Erik Hartvigsen, Harold Harvey, Paul Hatcher, James Hathorn, Robert Hathorn, Carolyn Hendricks, David Hesse, Martin Hightower, Peter Ho, Leroy Hoffman, Frankie Ann Holmes, Sidney Hopkins, Samuel Huang, Robert Huben, Cliff Hudis, Thelma Hurd, Sally Ingram, Philip Israel, Naresh Jain, Nora Jaskowiak, Jean Joseph, Jacqueline Joyce, Walton Joyner, Ray Joyner, Scott Kahn, Sachin Kamath, Carsten Kampe, Michael Kane, Richard Kane, Michael Kasper, Uday Kavde, Thomas Keeler, Douglas Kelly, Michael Kent, Kevin Kerlin, Kenneth Kern, Huathin Khaw, Jay Kim, Houston Kimbrough, Charmaine Kim-Sing, John Kishell, Petras Kisielius, George Kmetz, Lawrence Knott, Ronald Konchanin, Cyrus Kotwall, Kenneth Kotz, Charles Kraus, Bruce Kressel, Alan Kritz, John Lacey, Susan Laing, David Larson, Barry Lee, W. Robert Lee, Douglas Leet, Natasha Leighl, George Leight, Paul LeMarbre, Herbert Lepor, Seth Lerner, Margaret Levy, Lori Lilley, Steve Limentani, Robert Lineberger, Lenis Livesay, Fred J. Long, Richard Love, Mark Lucas, James Lugg, Charles Lusch, H. Kim Lyerly, Janet Macheledt, Thomas Maddox, Patrick Maguire, Mark Makhuli, Rajeev Malik, Mary Manascalco-Theberge, P. Kelly Marcom, Manfred Marcus, Neal Mariados, Lawrence Marks, Shona Martin, Eric Matayoshi, Gordon Mathes, Mark McClure, Scott McGinnis, David McLeod, Warren McMurry, William McNulty, Robert McWilliams, Cynthia Menard, Mani Menon, Richard Michaelson, Michael Mikolajczyk, David Miles, Dixie Mills, Jesse Mills, David Mintzer, David Molthorp, Allen Mondzac, Gustavo Montana, Angelica Montesano, Leslie Montgomery, Joseph O. Moore, William Morgan, Patricia Morrison, Michael A. Morse, Jacek Mostwin, Judd Moul, Brian Murphy, William Muuse, J. William Myers, Richard S. Myers, Richard Mynatt, Gene Naftulin, Vishwanath Nagale, Niam Nazha, Charles Neal, James Neidhart, Joseph D. Neighbors, Philip Newhall, Robert Nichols, William Niedrach, Peter Oh, John Oh, John A. Olson, Robert Ornitz, David Ornstein, Alexander Panutich, Maria Papaspyrou, Steven Papish, Dhaval Parikh, James Parsons, George Paschal, Robert Paterson, Dev Paul, David F. Paulson, Samuel Peretsman, Jorge Perez, Mark Perman, Thomas Polascik, Klaus Porzig, David C. Powell, Kenneth Prebil, Glenn Preminger, Adele Preto, Leonard Prosnitz, Robert Prosnitz, Scott K. Pruitt, Robert Reagan, Carl Reese, John Reilly, Robert Renner, Alan Rice, Melvin Richter, Adrien Rivard, Ralph Roan, Cary Robertson, Steve Robeson, Linda Robinson, Mark Romer, Eric Rosen, Amy Rosenthal, Alison Ross, William Russell, Lewis Russell, Charles Scarantino, Candace Schiffer, Mark Schoenberg, Mark Scholz, William Schuessler, Stuart Schwartzberg, Janell Seeger, Victoria Seewaldt, Hillard Seigler, Pearl Seo, Phillip Shadduck, Timothy Shafman, Rohit Shah, Arieh Shalhav, Peter Shapiro, Fred Shapiro, Heather Shaw, Robert Siegel, Daniel Silver, Mary Simmonds, Jane Skelton, Barbara Smith, Mitchell Sokoloff, Douglas Sorensen, Angela Soto-Hamlin, Alexander Sparkuhl, Thomas Spears, Merle Sprague, Mark St. Lezin, Steven J. Stafford, B. Dino Stea, Gary Steinberg, Patricia Steinecker, Mary Stewart, Jerry Stirman, Lewis Stocks, Christopher Stokoe, Warren Streisand, Mark Sturdivant, Paul Sugar, Steven Sukh, Perry Sutaria, Linda Sutton, Phillip Sutton, John Sylvester, Beth Szuck, Darrell Tackett, Ernesto Tan, Sharon Taylor, John Taylor, Dina Tebcherany, Chris Teigland, Marcos Tepper, Haluk Tezcan, William Thoms, Ellis Tinsley, Jr., Lisa Tolnitch, Angel Torano, Frank Tortora, William Truscott, Theodore Tsangaris, Peter Tucker, Walter Tucker, Ingolf Tuerk, Wade Turlington, Richard Tushman, Michael Tyner, Pascal Udekwu, Eric Uhlman, Linda Vahdat, Louis Vandermolen, George Vassar, Margaret Vereb, Johannes Vieweg, Daniel Vig, Tom Vo, Walter Vogel, David Wahl, B. Alan Wallstedt, Patrick Walsh, Philip Walther, Robert Waterhouse, Charles Wehbie, Seth Weinreb, Marissa Weiss, Raul Weiss, Geoffrey White, Edward Whitesides, Lee Wilke, Hamilton Williams, Matthew Wilner, Don Wilson, James S. Wilson, Bristol Winslow, Rachel Wissner, James Wolf, Lawrence Womack, Charles Woodhouse, Clifford Yaffe, Daniel Yao, Richard Yelverton, Lemuel Yerby, Mark Yoffe, Martin York, Gregory Zagaja, Kenneth Zeitler, Elizabeth Zubek, and Raul Zunzunegui). Most of all, we are indebted to the many cancer survivors who helped us pilot test, re-test, and then formally test the intervention.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Catherine E. Mosher, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Bernard F. Fuemmeler, Duke University Medical Center

Richard Sloane, Duke University Medical Center.

William E. Kraus, Duke University Medical Center

David F. Lobach, Duke University Medical Center

Denise Clutter Snyder, Duke University Medical Center.

Wendy Demark-Wahnefried, Duke University Medical Center.

References

- 1.Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland J, Mariotto A, Aziz N, Tesauro G, Feuer EJ. Cancer survivorship—United States, 1971–2001. MMWR. 2004;53:526–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aziz NM. Cancer survivorship research: Challenge and opportunity. J Nutr. 2002;132(suppl 11):3494S–3503S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3494S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Trends and advances in cancer survivorship research: Challenge and opportunity. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:248–266. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;7:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Survivorship. [cited 2007 July 19]. Available from: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/prevalence.

- 7.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: Findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Grant B, et al. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: An American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:323–353. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes. Nutr Clin Care. 2003;6:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, McTiernan A, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:254–281. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Fair JM, Fortmann SP, et al. AHA guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke: 2002 update. Circulation. 2002;106:388–391. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020190.45892.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479–2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Chan AT, Chan JA, Colditz GA, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–3534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: Findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3535–3541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, Nixon DW, Shapiro A, Hoy MK, et al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med. 2005;40:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: Promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–5830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stull VB, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W. Lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors: Designing programs that meet the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. J Nutr. 2007;137:243S–248S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Courneya KS. Exercise in cancer survivors: An overview of research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1846–1852. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093622.41587.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demark-Wahnefried W, Pinto BM, Gritz ER. Promoting health and physical function among cancer survivors: Potential for prevention and questions that remain. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5125–5131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall EL. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council: From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones LW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet, exercise, and complementary therapies after primary treatment for cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70976-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: A sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2709–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haines PS, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. The Diet Quality Index Revised: A measurement instrument for populations. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:697–704. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kant AK, Schatzkin A, Graubard BI, Schairer C. A prospective study of diet quality and mortality in women. JAMA. 2000;283:2109–2115. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mai V, Kant AK, Flood A, Lacey JV, Jr, Schairer C, Schatzkin A. Diet quality and subsequent cancer incidence and mortality in a prospective cohort of women. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:54–60. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuemmeler BF, Mâsse LC, Yaroch AL, Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, et al. Psychosocial mediation of fruit and vegetable consumption in the body and soul effectiveness trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25:474–483. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kristal AR, Glanz K, Tilley BC, Li S. Mediating factors in dietary change: Understanding the impact of a worksite nutrition intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:112–125. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langenberg P, Ballesteros M, Feldman R, Damron D, Anliker J, Havas S. Psychosocial factors and intervention-associated changes in those factors as correlates of change in fruit and vegetable consumption in the Maryland WIC 5 A Day Promotion Program. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:307–315. doi: 10.1007/BF02895667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baranowski T, Lin L, Wetter DW, Resnicow K, Hearn MD. Theory as mediating variables: Why aren’t community interventions working as desired? Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:S89–S95. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dishman RK, Motl RW, Saunders R, Felton G, Ward DS, Dowda M, et al. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Prev Med. 2004;38:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis BA, Forsyth LH, Pinto BM, Bock BC, Roberts M, Marcus BH. Psychosocial mediators of physical activity in a randomized controlled intervention trial. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2006;28:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller YD, Trost SG, Brown WJ. Mediators of physical activity behavior change among women with young children. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(suppl 2):98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00484-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto BM, Lynn H, Marcus BH, DePue J, Goldstein MG. Physical-based activity counseling: Intervention effects on mediators of motivational readiness for physical activity. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:2–10. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, Nail LM, Scherer J. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2007;56:18–27. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabin CS, Pinto BM, Trunzo JJ, Frierson GM, Bucknam LM. Physical activity among breast cancer survivors: regular exercisers vs. participants in a physical activity intervention. Psychooncology. 2006;15:344–354. doi: 10.1002/pon.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, McBride C, Lobach DF, Lipkus I, Peterson B, et al. Design of FRESH START: A randomized trial of exercise and diet among cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:415–424. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000053704.28156.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macri JM, Downs SM, Algoti S, Demark-Wahnefried W, Snyder DC, Lobach DF. A simplified approach to generating tailored questionnaires, health education messages and guideline recommendations. Comput Inform Nurs. 2005;23:316–321. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200511000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demark-Wahnefried W. Print-to-practice: Designing tailored print materials to improve cancer survivors’ dietary and exercise practices in the FRESH START trial. Nutr Today. 2007;42:131–138. doi: 10.1097/01.NT.0000277790.03666.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson M, Law M, dos Santos M, Greer S, Baruch J, Bliss J. The Mini-MAC: Further development of the Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1994;12:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prochaska JO. Treating entire populations for behavior risks for cancer. Cancer J. 2001;7:360–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson FE, Subar AF, Brown CC, Smith AF, Sharbaugh CO, Jobe JB, et al. Cognitive research enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire reports: Results of an experimental validation study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:212–225. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haines PS, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. The Diet Quality Index revised: a measurement instrument for populations. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:697–704. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blair SN, Haskell W, Ho P, Paffenbarger RS, Vranizan KM, Farquhar JW, et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:794–804. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pereira MA, FitzerGerald SJ, Gregg EW, Joswiak ML, Ryan WJ, Suminski RR, et al. A collection of physical activity questionnaires for health-related research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(suppl 6):S1–S205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campbell MK, Reynolds KD, Havas S, Curry S, Bishop D, Nicklas T, et al. Stages of change for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among adults and young adults participating in the national 5-a-Day for Better Health community studies. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:513–534. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krebs-Smith SM, Heimendinger J, Patterson BH, Subar AF, Kessler R, Pivonka E. Psychosocial factors associated with fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Health Promotion. 1995;10:98–104. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, Kalsbeek WD, Dodds J, Cowan A, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: The Black Churches United for Better Health Project. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1390–1396. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. Pulling cost-effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: A non-parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ. 1997;6:327–340. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199707)6:4<327::aid-hec282>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Effron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:171–200. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;18:289–298. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Pirzada A, Yan LL, Garside DB, Wang R, et al. Relationship of fruit and vegetable consumption in middle-aged men to medicare expenditures in older age: the Chicago Western Electric Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1735–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, Hu FB, Hunter D, Smith-Warner SA, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1577–1584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M. The burden of cardiovascular disease and cancer attributable to low fruit and vegetable intake in the European Union: differences between old and new Member States. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:575–583. doi: 10.1079/phn2005910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.James AS, Campbell MK, DeVellis B, Reedy J, Carr C, Sandler RS. Health behavior correlates among colon cancer survivors: NC STRIDES baseline results. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30:720–730. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.6.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Alcaraz JE, Gehrman C, Johnson MF. Potential mediators of change in a physical activity promotion course for university students: Project GRAD. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21:149–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02908296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anderson RT, King A, Stewart AL, Camacho F, Rejeski WJ. Physical activity counseling in primary care and patient well-being: Do patients benefit? Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:146–154. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bock BC, Marcus BH, Pinto BM, Forsyth LH. Maintenance of physical activity following an individualized motivationally tailored intervention. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:79–87. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hallam JS, Petosa R. The long-term impact of a four-session work-site intervention on selected social cognitive theory variables linked to adult exercise adherence. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:88–100. doi: 10.1177/1090198103259164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Nair VN, Strecher VJ. A strategy for optimizing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:65–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]