Abstract

Introduction

Intradural lumbar disc herniations are uncommon presentations of a relatively frequent pathology, representing less than 1% of all lumbar disc hernias. They show specific features concerning their clinical diagnosis, with a higher incidence of cauda equina syndrome, and their surgical treatment requires a transdural approach.

Methods

In this article, we describe five cases of this pathology and review the literature as well as some considerations about the difficulties in the preoperative diagnostic issues and the surgical technique.

Conclusion

We concluded that for intradural disc herniations the diagnosis is mainly intraoperative, and the surgical technique has some special aspects.

Keywords: Intradural herniation, Lumbar herniated disc, Cauda equina syndrome, Microdiscectomy

Introduction

Intradural disc herniation (IDH) is defined as the intervertebral disc nucleus pulposus displacement into the dural sac [1]. It was originally described by Dandy [2] in 1942, with an amount of circa 140 cases reported in literature until 2009 [3].

IDH is rare, comprising only 0.26–0.30 % of all disc herniations, and it occurs more often in the lumbar region (92 %) [4, 5], in which the L4–L5 disc space is the most frequently attempted (55 %), followed by the L3–L4 (16 %) and then by the L5–S1 (10 %) [1].

The IDH etiopathogenesis is unclear, but some surgical and anatomopathological findings indicate a possible attachment between the anterior dura and the annulus fibrosus, conditions which would facilitate the nucleus pulposus herniation into the dural sac [3, 4, 6].

Clinically, there is a higher incidence of cauda equina syndrome (CES) in IDH than in extradural herniations [3, 6, 7] and despite the advance of present neuroimaging techniques, it is not yet possible to establish accurately whether a disc herniation is located intradurally [1]. The diagnosis is only confirmed at surgical field in most cases.

We present five cases of IDH seen between May 2008 and February 2012, and discuss specific aspects of the diagnosis, etiopathogenesis, and surgical findings.

Case reports

The reported cases are summarized in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of the cases

| Case | Age | Gender | Herniation level | Symptoms | Duration | Evolution in 3 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | F | L4–L5 | Acute urinary retention, perineal hypoesthesia and right L5–S1 radiculopathy | 2 days | Improvement of bladder control, no urinary incontinence. Improvement of the right L5–S1 radiculopathy with mild perineal hypoesthesia |

| 2 | 71 | M | L4–L5 | Urinary retention, perineal hypoesthesia, left L5–S1 radiculopathy | 7 days | Complete resolution of the symptoms |

| 3 | 49 | F | L5–S1 | Urinary incontinence, perineal hypoesthesia and left S1 radiculopathy | 3 weeks | Improvement of urinary incontinence and lumbosciatic pain relief; persistency of mild perineal hypoesthesia |

| 4 | 68 | F | L4–L5 | Left lumbar and sciatic pain, with left L5–S1 hypoesthesia | 2 years | Complete resolution of the symptoms |

| 5 | 46 | F | L4–L5 | Left lumbar and sciatic pain, with left L5–S1 hypoesthesia | 2 weeks | Complete resolution of the symptoms |

Case 1: A 44-year-old female suffered from mild and intermittent chronic lumbar pain for the last 2 years with significant worsening during the last month. Urinary retention began 2 days before hospitalization, along with perineal hypoesthesia, right L5–S1 hypoesthesia, and motor deficit involving right foot extension and flexion. Magnetic resonance image (MRI) suggested a voluminous and extruded L4–L5 disc herniation. After the surgical procedure, the patient evolved with improvement in bladder control and motor and sensitive deficits of her right foot, but she persisted presenting perineal hypoesthesia during 6 months after the surgery.

Case 2: A 71-year-old male was operated on an L4–L5 disc herniation 2 years ago by another neurosurgical team. He has shown lumbar pain recurrence for the last 3 months and urinary incontinence since last week. On neurological examination, he presented perineal and anterolateral left foot hypoesthesia, motor deficit during left foot flexion and extension, and left achillean hyporeflexia. MRI showed a voluminous L4–L5 disc herniation occupying great portion of the vertebral canal (Fig. 1). At the postoperative period, the patient showed immediate cessation of all his symptoms (pain and urinary incontinence), the strength of his left leg was normal 3 months after the surgery, and he remains asymptomatic 6 months postoperatively.

Fig. 1.

T2W MRI showing a huge L4–L5 herniated disc

Case 3: A 49-year-old female with low back pain and left sciatic pain for the last 8 years, worsening during the last 2 years. Since 3 weeks, she has had complaints of perineal hypoesthesia and urinary loss during efforts. MRI showed voluminous L5–S1 disc herniation with caudal migration, causing an obstruction of the vertebral canal at this level. This patient was operated and presented significant pain relief and urinary incontinence improvement, although there was mild perineal hypoesthesia persistence at the 6 month postoperative period.

Case 4: A 68-year-old female presented with lumbar complaints and left sciatic pain for the last 2 years, with progressive worsening. On neurological examination we observed left achillean hyporeflexia, left L5–S1 territories hypoesthesia, absence of motor deficit or sphincter disorder. MRI showed a voluminous L4–L5 posterior disc herniation with mixed signal (hypo and hypersignal), and surgery was then indicated. The patient showed 80 % pain relief at 2 months postoperatively and complete relief after 6 months.

Case 5: A 46-year-old man presented with a history of low back pain for 3 years. Two weeks before surgery, he underwent a session of spinal manipulation, and since then developed important symptoms of sciatica in his left leg, comprising mostly the L5 and S1 roots, with anterolateral foot hypoesthesia, but without motor strength deficits. Laségue’s sign was positive at 15°. MRI showed the image of an extruded lumbar disc herniation at the level L4–L5. At the postoperative period, the patient was pain free, with no neurologic deficits or CSF leak.

In all the cases a similar surgical technique was performed. Initially, a conventional interlaminar microdiscectomy approach was proposed. After a small interlaminar fenestration and the exposure of the dural sac, we experienced great difficulty to dissect the anterolateral aspect of the dural sheath, which was closely attached to the peridural space. In addition, we observed an extremely tense dura. So, we decided to extend the exposure by performing hemilaminectomies upward and downward. After extensive failed search for extradural disc fragments and after double-checking the disc level, the suspicion of IDH was raised and a posterior median dural incision with intradural inspection was performed. Under surgical microscopic magnification and using microsurgical techniques, we separated the nervous rootlets and found the intradural disc fragments, which revealed a communication between the dural sac and the posterior longitudinal ligament after being removed, as well as a communication with the disc space. After decompression, the anterior dural sheath tear was not sutured, only a hemostatic material was placed to occlude it. The posterior dural incision was sutured with continuous stitches; the soft tissues were closed ordinarily.

Discussion

Intradural lumbar disc herniations are rare conditions, comprising 0.26–0.30 % of all disc herniations [4, 5]. Between May 2008 and February 2012, the authors have performed 283 surgeries for degenerative lumbar disc disease, and found five cases of IDH, with an incidence of 1.76 %. This number is slightly greater than the incidence found in most of the published articles. Maybe it can be explained because after the difficulty found in the first case, in all other cases of herniated lumbar disc when the dissection of the dural sac was difficult or when the amount of disc fragment obtained was less than that expected by the surgeon, we performed a durotomy to explore the intradural compartment looking for other free fragments. With this maneuver, maybe we have found some herniations that would have been missed earlier.

The etiopathogenesis of IDH is not yet clearly understood. Several authors have found in autopsies the presence of adhesions between the ventral dural sheath and the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL), which are loose in most cases. However, in some cases, these adhesions may be extremely resistant, unable to be separated through sharpless dissection [6, 7], being an important predisposing factor. Such adhesions occur more often in L4–L5 space, which justifies a higher incidence of intradural disc herniations at this level, being more prevalent in patients with history of previous lumbar pain [6]. One believes that patients with degenerative disc pathologies would present a chronic inflammatory process, which would favor the occurrence of these adhesions, leading to erosions on the adjacent dural sheath [7–11]. Nevertheless, IDH can have congenital origin: such adhesions have also been found in stillborn autopsies [4, 7]. These kinds of adhesions have also been proposed as the etiopathogenesis of a radicular interdural lumbar disc herniation, as described by Akhaddar et al. [12]. In their paper, the assumption is that this condition may be an intermediate phase before a complete intradural herniation.

Other predisposing conditions stated in the literature are congenital reduction of dural thickness, vertebral canal congenital stenosis [1], and previous surgeries [10]. All five cases reported in this paper presented adhesions between the dural sac and the PLL, and one case had previous surgery at the same level of the IDH.

Concerning the symptomatology, there are no differences in clinical signs between extradural and IDH [12], although CES is more frequent in the presence of IDH [3, 6, 7]. This syndrome occurs in approximately 0.5–1 % of lumbar disc herniations in general [13, 14], while it is described in up to 30 % of the IDH [1]. Three of our patients (comprising 60 %) presented some degree of cauda equine syndrome.

Until now there is no plausible explanation for this phenomenon. We believe that the PLL together with the dural sheath offer resistance against massive nucleus pulposus herniations, however, once this resistance is overcome by the disc fragment, which is then located inside the dural sac, this resistance becomes weakened and permits a herniation of a larger amount of nucleus pulposus. Besides, one should consider that, theoretically, there is a release of chemical substances by the nucleus pulposus once in contact with the intradural lumbar rootlets, what may cooperate to the presence of most evident neurological symptoms.

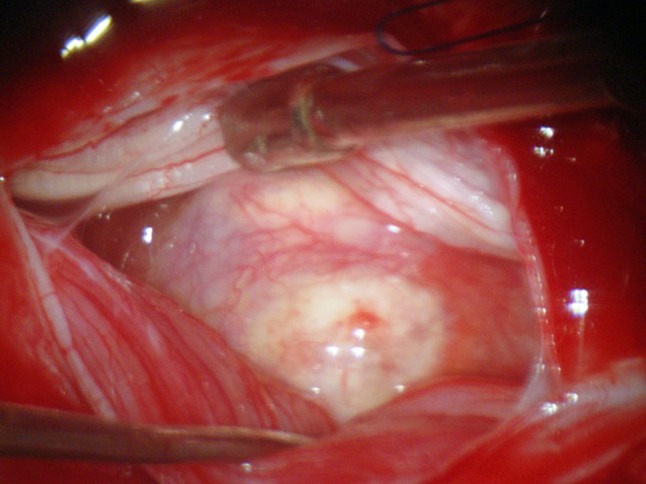

Various neuroimaging techniques have been employed to try to locate more accurately the position of the disc herniation, but despite the advance and refinement of present techniques, the final diagnosis of IDH is only mostly made during the intraoperative period [1] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative aspect of the herniated disc

MRI is the gold standard neuroimaging study. The usual image is of a voluminous disc herniation occupying most part of the vertebral canal, with hyposignal both in T1 and T2. Two following characteristics may be associated to IDH: the loss of continuity of the PLL shown in sagittal acquisitions and the “hawk-beak” sign in axial T2 acquisitions, which show a triangular aspect of the herniated disc compressed laterally by the cartilaginous edges of the annulus fibrosus [15, 16]. After contrast injection there may be a ring enhancement of the herniated portion of the disc by the gadolinium. This enhancement is caused by the granulation tissue that originated at the edge of the herniation and its neovascularization. However, the IDH imaging can be indistinguishable from the lumbar extradural ones. Other spinal pathologies must be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as neurofibroma, lipoma, meningioma, epidermoid tumor, arachnoid cyst, arachnoiditis and metastasis [16].

No patient hereby reported has received contrast injection for this procedure. It is not routinely performed during lumbar magnetic resonance exams; however, we consider contrast injection magnetic resonance imaging should be performed when there is suspicion of IDH.

Regarding its treatment, some surgical aspects should be highlighted. The difficulty in dissecting the dural sheath anterolateral portions is a frequent finding. In all five reported cases we found adhesions between the disc space and the PLL, as described by other authors. Blikra [6], in one of the former reports of this pathology, already set light to the fact that there are dense adhesions between the disc space and the dural sac detected in the intraoperative phase. Aydin and Lee [3, 4] have also found these difficulties, describing the dural sac as being harsh, tense and motionless.

Thus, we suggest a median or paramedian dural incision followed by microsurgical approach in cases where there is difficulty on dissecting the anterolateral portion of the dural sheath from the posterior aspect of the intervertebral disc, and in cases where the presence of extradural disc herniation at the accurate level of the lesion is not clear.

The use of surgical microscope is primordial for good visualization of the herniation after the dural incision, minimizing injuries to the nervous rootlets [7]. The anterior dural sheath tear should only be sutured when there is no risk to the surrounding rootlets, once its tight closure is not absolutely necessary. In our four cases it was not possible to perform primary suture of the anterior dural tear. As reported by other authors [7], the anterior dural tear is difficult to be closed by primary suture. We have only occluded it with hemostatic material, and we advice absolute rest during 48 h in the postoperative period. Our patients presented neither cerebrospinal fluid leak, nor other complications.

The prognosis is related to the duration of symptoms, the kind of symptoms (radiculopathy vs. CES) and the presence of previous surgery [1]. In cases where there are symptoms of cauda equina compression, the recovery of symptoms takes longer and can be incomplete. In CES, the prognosis is mainly related to the time elapsed from the beginning of the symptoms till the surgery, which must be performed within the first 48 h [17].

All patients reported here with cauda equina syndrome presented significant relief of the pain and of the neurological symptoms in the postoperative period, although only one patient had undergone surgery within this ideal period of time. We have also observed that the motor recovery was superior to the sensitive one; data similar to those were found in literature [13]. The patients presenting only radicular pain preoperatively had complete recovery after the surgical procedure, without neurological deficits, demonstrating that the gentle manipulation of the rootlets under microscopical augmentation does not cause neurological dysfunction.

Conclusion

Lumbar IDH are very rare pathologies, and despite the accuracy of present imaging tests, the confirmation occurs only in the intra-operative period. One should pay attention to some characteristics of this pathology, mainly the intraoperative difficulty on dissecting the anterolateral aspect of the dural sac from the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.D’Andrea G, Trillo G, Roperto R, Celli P, Orlando ER, Ferrante L. Intradural lumbar disc herniations: the role of MRI in preoperative diagnosis and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27:75–80. doi: 10.1007/s10143-003-0296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dandy WE. Serious complications of ruptured intervertebral disks. JAMA. 1942;119:474–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.1942.02830230008002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JS, Suh KT. Intradural disc herniation at L5–S1 mimicking an intradural extramedullary spinal tumor: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:778–780. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.4.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aydin MV, Ozel S, Sem O, Erdogan B, Yildirim T. Intradural disc mimicking: a spinal tumor lesion. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:52–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein NE, Syrquin MS, Epstein JA, Decker RE. Intradural disc herniations in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine: report of three cases and review of the literature. J Spinal Disord. 1990;3(4):396–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blikra G. Intradural herniated lumbar disc. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:676–679. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.31.6.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yildizhan A, Pasaoglu A, Okten T, Ekinci N, Aycan K, Aral O. Intradural disc herniations: pathogenesis, clinical picture, diagnosis and treatment. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;110(3–4):160–165. doi: 10.1007/BF01400685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesoin F, Duquennoy B, Rousseaux M, Servato R, Jomin M. Intradural rupture of lumbar intervertebral disc: report of three cases with review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1984;14(6):728–731. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198406000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teng P, Papathedodorou C. Intrathecal dislocation of lumbar intervertebral disc. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1964;7:57–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1095409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han IH, Kim KS, Jin BH. Intradural lumbar disc herniation associated with epidural adhesion: report of two cases. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46:168–171. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.46.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floeth F, Herdmann J. Chronic dura erosion and intradural lumbar disc herniation: CT and MR imaging and intraoperative photographs of a transdural sequestrectomy. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl 4):453–457. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhaddar A, Boulahroud O, Elasri A, Elmostarchid B, Boucetta M. Radicular interdural lumbar disc herniation. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(Suppl 2):S149–S152. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1200-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kardaun JW, White LR, Shaffer WO. Acute complications in patients with surgical treatment of lumbar herniated disc. J Spinal Disord. 1990;3(1):30–38. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro S. Medical realities of cauda eqüina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(3):348–351. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JY, Lee SW, Sung KH. Intradural lumbar disc herniation—is it predictable preoperatively? A report of two cases. Spine J. 2007;7:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CC, Huanjg CT, Lin CM, Liu KN. Intradural disc herniation at L5 level mimicking an intradural spinal tumor. Eur Spine J. 2011;Suppl 2:S326–S329. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arrigo RT, Kalanithi P, Boakye M. Is cauda eqüina syndrome being treated within the recommended time frame? Neurosurgery. 2011;68(6):1520–1526. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820cd426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]