Abstract

Unstable microhabitats (merocenoses)—such as decayed wood, ant hills, bird and mammal nests—constitute an important component of forest (and non-forest) environments. These microhabitats are often inhabited by specific communities of invertebrates and their presence increases the total biodiversity. The primary objective of the present study was to compare communities of Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) inhabiting soil and unstable microhabitats in order to explore the specificity of these communities and their importance in such ecosystems. Uropodine communities inhabiting merocenoses are often predominated by one or two species, which constitute more than 50 % of the entire community. Many species occur commonly in particular merocenoses, but are absent or rare in soil and litter, for example, Allodinychus flagelliger, Metagynella carpatica, Oplitis alophora, and Phaulodiaspis borealis. The biology of Uropodina inhabiting unstable microhabitats is modified by the adaptations required for living in such habitats. Mites associated with merocenoses developed special dispersal mechanisms, such as phoresy, which enable them to migrate from disappearing environments. Communities of Uropodina in soil and litter predominately consisted of species which reproduce parthenogenetically (thelytoky), whereas in merocenoses bisexual species prevail.

Keywords: Uropodina, Community structure, Soil, Decayed wood, Bird nests, Mammal nests

Introduction

Unstable microhabitats (merocenoses), such as decayed wood, ant hills, bird nests and mammal nests, are often scattered, small and ephemeral. As opposed to soil and litter, merocenoses have different environments in terms of the food, physio-chemical, and microclimatic conditions. Merocenoses are characterized by higher and relatively stable humidity during the year. Humidity is highly significant for mites from the suborder Uropodina (Acari: Mesotigmata) because mesohigrophilic species constitute the majority of these mites (Athias-Binche and Habersaat 1988; Krištofík et al. 1993; Błoszyk et al. 2001, 2004; Błoszyk and Bajaczyk 1999). Decayed wood, ant hills, bird nests, and mammal nests are important components of natural ecosystems—both forest and non-forest open environments, such as meadows, xerophilous grasses, and peat-bogs. Unstable microhabitats are often inhabited by specific communities of invertebrates, thus increasing the total biodiversity of the environment (Krištofík et al. 1993; Gwiazdowicz et al. 2000; Gwiazdowicz and Sznajdrowski 2000; Błoszyk et al. 2003a; Bajerlein and Błoszyk 2004; Gwiazdowicz and Klemt 2004; Gwiazdowicz and Kmita 2004).

The specific characteristics of merocenoses are favorable only for species with special reproduction and dispersal abilities, enabling them not only to colonize and populate these microhabitats, but also to escape from the vanishing habitat when the food resources become limited, to find a new suitable habitat (Athias-Binche 1984, 1993, 1994; Faasch 1967). Uropodina use representatives of various orders of insects and centipedes as carriers (Mašán 2001). The carrier organisms enable the mites to cover distances between merocenoses and find microhabitats with a suitable microclimate and sufficient food resources. Phoretic deutonymphs of Uropodina have a special anal apparatus (pedicel), which enables a mite to stick to the carier’s body (Athias-Binche 1984; Błoszyk et al. 2006b). The structural complexity of the anal apparatus shows that Uropodina have probably had this ability for a very long time and no other group of mites has adapted to phoresy (Athias-Binche 1984).

Very few studies in the acarological literature adduce data about habitat preferences and assimilation abilities of Uropodina species, both to living in soil and specific merocenoses (Athias-Binche 1979, 1982a, b, 1983; Błoszyk (1992); Huţu 1993; Błoszyk 1999; Mašán 2001). The scant evidence obtained so far suggests that the biology of these species is modified by adaptation to living in each of these habitats. The observations carried out by Błoszyk et al. in different habitats in Poland have revealed differences in species composition and community structure of mites from the suborder Uropodina. The differences are most evident in the case of unstable microhabitats (Błoszyk 1980, 1983, 1985, 1999; Bloszyk and Olszanowski 1985a, b, 1986; Błoszyk et al. 2003a; Napierała et al. 2009). The reproductive strategies also appear to differ between the two community types (Błoszyk et al. 2004).

The studies on communities in unstable microhabitats help to understand the biology and ecology of uropodine mites, and offer an insight into functioning of such ecosystems. However, most papers published so far are based on rather small data sets and have a local character, which means that they deal with one type of merocenoses. Many papers have been published in local journals and are not in English, which makes them inaccessible for many potential readers (Błoszyk 1985, 1990; Błoszyk and Olszanowski 1985a, b, 1986; Błoszyk and Bajaczyk 1999; Gwiazdowicz et al. 2000, 2005, 2006; Bajerlein and Błoszyk 2004; Gwiazdowicz and Klemt 2004; Gwiazdowicz and Kmita 2004; Błoszyk and Gwiazdowicz 2006). The aim of the present study is to compare the communities of Uropodina inhabiting soil and unstable microhabitats to establish the features common for all merocenoses and what makes them different from soil environment. None of the studies published hitherto is based on such a large amount of material, collected during such a long period of time.

The main hypothesis is that in merocenoses there are one or two species that dominate the community, whereas in soil there is no strong dominance of one species. The second hypothesis is that parthenogenetic species prevail in soil, whereas bisexual species dominate in unstable microhabitats, depending on the variation in stability and size of these environments. The third hypothesis postulated here is that the presence of microhabitats in ecosystems increases the total biodiversity of uropodine fauna in such environments.

Materials and methods

Mite collection and extraction

The material for this study has been collected since 1951 in different parts of Poland (most samples come from Wielkopolska, Poland). Every month between 2001 and 2004 the soil and dead wood samples were collected in three nature reserves—Huby Grzebieniskie, Bytyńskie Brzęki, and Brzęki przy Starej Gajówce. They belong to a forest complex at about 25 km west-north-west from Poznań (for a detailed description see Napierała et al. 2009).

The soil was sampled quantitatively (core samples of 30 cm2 surface and 10 cm deep) and qualitatively (sieve samples). The mites were also collected from 0.5–0.8 l samples of different types of dead wood (rotten trunks, logs, and stumps). The mites were extracted with Tullgren funnels for ca. 4–6 days (depending on the level of moisture), and preserved in 75 % alcohol. Both permanent and temporary microscope slides were made (mounted in Hoyer’s medium), and the specimens were identified with the keys in Kadite and Petrova (1977), Evans and Till (1979), Karg (1989), Błoszyk (1999), and Mašán (2001). The 16,323 samples were collected and deposited in a soil-fauna database (Natural History Collections, Faculty of Biology AMU, Poznań); 13,996 samples were collected from soil, 978 from dead wood, 238 from tree holes, 233 from mammal nests, 836 from bird nests, and 42 from ant hills.

Data analysis

The zoocenological analysis of Uropodina communities is based on the indices of the dominance and frequency. The following classes were used (Błoszyk 1999):

Dominance: D5, eudominants (>30 %), D4, dominants (15.1–30.0 %), D3, subdominants (7.1–15.0 %), D2, residents (3.0–7.0 %), and D1, subresidents (<3 %).

Frequency: F5, euconstants (>50 %), F4, constants (30.1–50 %), F3, subconstants (15.1–30.0 %), F2, accessory species (5.0–15.0 %), and F1, accidents (<5 %).

The community similarity was calculated by means of the Marczewski-Steinhaus species similarity index: MS = c/(a + b − c), where c is the number of species present in both compared communities, and a and b stand for the total numbers of species in each community (Magurran 2004).

The differences between the average abundances in the merocenoses and soil were analysed with Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA and Dunn tests. The mean abundances of the selected dominant species of Uropodina in the soil and dead wood in the three nature reserves of Wielkopolska were analysed with Mann–Whitney U tests. All tests were calculated in STATISTICA 6.0 Pl.

Results

The total number of Uropodina collected in the presented material is 74 species (Table 1): 68 species (108,737 specimens) were found in the soil, 51 (19,843 specimens) in dead wood, 34 (3,069 specimens) in tree holes, 30 (7,696 specimens) in mammal nests, 28 (7,741 specimens) in bird nests, and 12 (871 specimens) in ant hills (Table 2).

Table 1.

List of Uropodina species found in the analysed material

| Species | Total | Adult | Juvenile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Deutonymph | Protonymph | Larva | ||

| Trachytes aegrota (C. L. Koch, 1841) | 32,495 | 18,671 | 3 | 10,619 | 2,414 | 788 |

| Trachytes irenae (Pecina, 1970) | 11,450 | 3,012 | 4,501 | 3,176 | 588 | 173 |

| Trachytes lamda (Berlese, 1903) | 449 | 206 | 7 | 156 | 71 | 9 |

| Trachytes minima (Trägårdh, 1910) | 559 | 285 | 222 | 38 | 9 | 5 |

| Trachytes montana (Willmann, 1953) | 21 | 20 | 1 | |||

| Trachytes pauperior (Berlese, 1914) | 7,683 | 3,396 | 31 | 2,326 | 1,257 | 673 |

| Trachytes splendida (Hutu, 1973) | 8 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Polyaspinus cylindricus (Berlese, 1916) | 1,345 | 818 | 322 | 133 | 72 | |

| Polyaspinus schweizeri (Hutu, 1976) | 11 | 7 | 4 | |||

| Apionoseius infirmus (Berlese, 1887) | 1,567 | 429 | 345 | 652 | 138 | 3 |

| Polyaspis patavinus (Berlese, 1881) | 328 | 108 | 71 | 114 | 30 | 5 |

| Polyaspis sansonei (Berlese, 1916) | 165 | 30 | 33 | 60 | 24 | 18 |

| Uroseius hunzikeri (Schweizer, 1922) | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Iphidinychus gaieri (Schweizer, 1961) | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Discourella modesta (Leonardi, 1889) | 335 | 296 | 1 | 28 | 8 | 2 |

| Trematurella elegans (Kramer, 1882) | 700 | 263 | 281 | 132 | 18 | 6 |

| Oodinychus karawaiewi (Berlese, 1903) | 8,595 | 2,595 | 2,875 | 1,895 | 1,139 | 91 |

| Oodinychus obscurasimilis (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1961) | 432 | 184 | 214 | 25 | 8 | 1 |

| Oodinychus ovalis (C. L. Koch, 1839) | 21,586 | 5,997 | 6,022 | 4,645 | 3,760 | 1,162 |

| Oodinychus spatulifera (Moniez, 1892) | 796 | 373 | 339 | 82 | 2 | |

| Iphiduropoda penicillata (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1961) | 35 | 21 | 11 | 3 | ||

| Leiodinychus orbicularis (C. L. Koch, 1839) | 2,911 | 998 | 816 | 902 | 171 | 24 |

| Pseudouropoda calcarata (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1961) | 56 | 27 | 21 | 7 | 1 | |

| Pseudouropoda structura (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1961) | 5 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Pseudouropoda tuberosa (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1961) | 14 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Pseudouropoda sp. | 215 | 118 | 36 | 52 | 9 | |

| Urodiaspis tecta (Kramer, 1876) | 8,989 | 6,702 | 1,516 | 585 | 186 | |

| Urodiaspis stammeri (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 461 | 228 | 226 | 4 | 3 | |

| Urodiaspis pannonica (Willmann, 1952) | 1,976 | 1,252 | 522 | 147 | 55 | |

| Olodiscus kargi (Hirschamann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 253 | 144 | 86 | 22 | 1 | |

| Olodiscus minima (Kramer, 1882) | 15,585 | 12,647 | 56 | 2,066 | 563 | 253 |

| Olodiscus misella (Berlese, 1916) | 757 | 609 | 133 | 7 | 8 | |

| Neodiscopoma splendida (Kramer, 1882) | 2,741 | 940 | 1,241 | 396 | 153 | 11 |

| Cilliba cassidea (Herman, 1804) | 208 | 84 | 92 | 25 | 7 | |

| Cilliba cassideasimilis (Błoszyk, Stachowiak, Halliday 2007) | 1,458 | 471 | 587 | 255 | 105 | 40 |

| Cilliba erlangensis (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 104 | 84 | 4 | 16 | ||

| Cilliba rafalskii Błoszyk, (Stachowiak, Halliday 2007) | 620 | 369 | 122 | 73 | 56 | |

| Cilliba selnicki (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 120 | 50 | 66 | 2 | 2 | |

| Uroobovella fracta (Berlese, 1916) | 4 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Uroobovella marginata (C. L. Koch, 1829) | 32 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 2 | |

| Uroobovella obovata (Canestrini et Berlese, 1884) | 145 | 74 | 53 | 18 | ||

| Uroobovella pulchella (Berlese, 1904) | 3,908 | 1,687 | 96 | 1,241 | 692 | 192 |

| Uroobovella pyriformis (Berlese, 1920) | 2,618 | 1,077 | 879 | 546 | 104 | 12 |

| Uroobovella sp. | 23 | 15 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Fuscouropoda appendiculata (Berlese, 1910) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Allodinychus flagelliger (Berlese, 1910) | 298 | 64 | 40 | 136 | 56 | 2 |

| Phaulodiaspis advena (Trägårdh, 1912) | 1,063 | 227 | 213 | 509 | 105 | 9 |

| Phaulodiaspis borealis (Sellnick, 1940) | 3,229 | 939 | 763 | 1,403 | 118 | 6 |

| Phaulodiaspis rackei (Oudemans, 1912) | 1,483 | 458 | 556 | 377 | 85 | 7 |

| Uroplitella conspicua (Berlese, 1903) | 22 | 19 | 3 | |||

| Uroplitella paradoxa (Canestrini et Berlese, 1884) | 22 | 18 | 4 | |||

| Oplitis alophora (Berlese, 1903) | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Oplitis wasmanni (Kneissl, 1907) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Oplitis sp. | 5 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Trachyuropoda coccinea (Michael, 1891) | 152 | 82 | 58 | 9 | 3 | |

| Trachyuropoda poppi (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Trachyuropoda willmanni (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 17 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 2 | |

| Urotrachytes formicarius (Lubbock, 1881) | 22 | 7 | 14 | 1 | ||

| Dinychura cordieri (Berlese, 1916) | 509 | 226 | 154 | 94 | 35 | |

| Uropolyaspis hamulifera (Berlese, 1904) | 20 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 2 | |

| Discourella (?) baloghi (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 999 | 349 | 336 | 287 | 24 | 3 |

| Uropoda italica (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Uropoda orbicularis (Muller, 1776) | 584 | 62 | 8 | 490 | 24 | |

| Uropoda undulata (Hirschmann et Z.-Nicol, 1969) | 38 | 25 | 12 | 1 | ||

| Nenteria breviunguiculata (Willmann, 1949) | 1,751 | 416 | 273 | 897 | 152 | 13 |

| Nenteria floralis (Karg 1986) | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Nenteria stylifera (Berlese, 1904) | 53 | 31 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 1 |

| Dinychus arcuatus (Trägårdh, 1922) | 408 | 150 | 185 | 59 | 14 | |

| Dinychus carinatus (Berlese, 1903) | 1,009 | 311 | 290 | 302 | 88 | 18 |

| Dinychus inermis (C. L. Koch, 1841) | 339 | 154 | 132 | 42 | 11 | |

| Dinychus perforatus (Kramer, 1882) | 3,481 | 1,120 | 1,361 | 785 | 197 | 18 |

| Dinychus woelkiei (Hirschmann et Zirngiebl-Nicol, 1969) | 495 | 100 | 122 | 208 | 65 | |

| Metagynella carpatica (Balogh, 1943) | 163 | 14 | 12 | 131 | 6 | |

| Protodinychus punctatus (Evans, 1957) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 147,957 | 69,101 | 23,794 | 37,897 | 13,240 | 3,925 |

Table 2.

Occurrence of Uropodina in studied microhabitats

| Species | Soil | DW | TH | NM | NB | AH | No. of habitats where species was found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. aegrota | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Oo. karawaiewi | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Oo. ovalis | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Uro. pyriformis | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Din. perforatus | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| T. irenae | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| A. infirmus | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Po. patavinus | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Tre. elegans | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| I. penicillata | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| L. orbicularis | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Pseudouropoda sp. | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Ur. tecta | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Ol. minima | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Uro. obovata | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Din. arcuatus | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Din. carinatus | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Din. woelkiei | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Uroobovella sp. | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Oo. spatulifera | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| T. pauperior | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Ur. pannonica | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| P. cylindricus | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Ol. misella | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Ne. splendida | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Tr. coccinea | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| Ps. calcarata | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| U. orbicularis | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| N. breviunguiculata | + | + | + | + | 4 | ||

| T. montana | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Dis. baloghi | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Uro. pulchella | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Po. sansonei | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Oo. obscurasimilis | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| C. cassideasimilis | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Dis. modesta | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| D. cordieri | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Ph. rackei | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Uro. marginata | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Din. inermis | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| Urlop. paradoxa | + | + | + | 3 | |||

| T. lamda | + | + | 2 | ||||

| T. minima | + | + | 2 | ||||

| P. schweizeri | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Ps. structura | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Ps. tuberosa | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Ur. stammeri | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Ol. kargi | + | + | 2 | ||||

| C. erlangensis | + | + | 2 | ||||

| C. rafalskii | + | + | 2 | ||||

| C. selnicki | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Uropl. conspicua | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Urop. hamulifera | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Ph. advena | + | + | 2 | ||||

| N. stylifera | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Oplitis sp. | + | + | 2 | ||||

| Al. flagelliger | + | + | 2 | ||||

| C. cassidea | + | 1 | |||||

| Urot. formicarius | + | 1 | |||||

| U. undulata | + | 1 | |||||

| F. appendiculata | + | 1 | |||||

| Ne. splendida | + | 1 | |||||

| Tr. willmanni | + | 1 | |||||

| Ip. gaieri | + | 1 | |||||

| Uro. fracta | + | 1 | |||||

| Opl. wasmanni | + | 1 | |||||

| Tr. poppi | + | 1 | |||||

| U. italica | + | 1 | |||||

| Pr. punctatus | + | 1 | |||||

| M. carpatica | + | 1 | |||||

| Opl. alophora | + | 1 | |||||

| Uros. hunzikeri | + | 1 | |||||

| Ph. borealis | + | 1 | |||||

| N. floralis | + | 1 | |||||

| No. of species | 68 | 51 | 34 | 30 | 28 | 12 |

Soil soil and litter, DW dead wood, TH tree holes, NM mammal nests, NB bird nests, AH ant hills

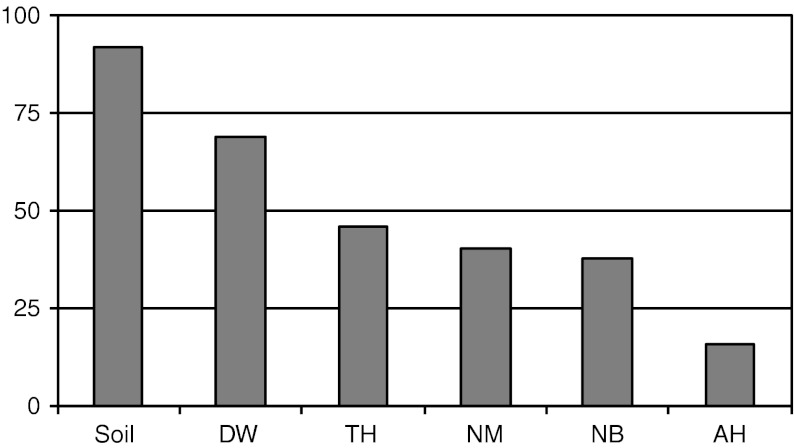

In the analysed microhabitats, most species (69 % of the whole Polish fauna) occurred in dead wood, whereas the lowest number of species (16 %) was observed in ant hills. The other microhabitats contained similar percentages (38–46) of the Polish fauna of Uropodina (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of species found in soil and various microhabitats with reference to the total number of species in Poland: soil soil and litter, DW dead wood, TH tree holes, NM mammal nests, NB bird nests, AH ant hills

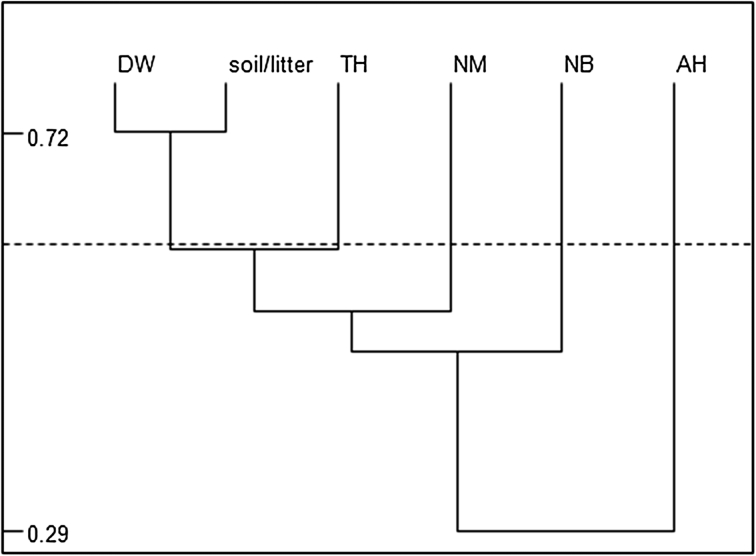

The bird nests and dead wood had the highest average number of mites, whereas ant hills had the lowest average number of mites. The most striking similarities in species composition (72 %) were found between the communities in the soil and the communities of Uropodina inhabiting the merocenoses of dead wood. The most distinct communities (29 % similarity) occurred in ant hills (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Similarity (S) of species composition of the communities of Uropodina in soil and in the analysed microhabitats: soil soil and litter, DW dead wood, TH tree holes, NM mammal nests, NB bird nests, AH ant hills

Species composition and community structure in analysed merocenoses

The highest frequency of Uropodina (>50 %) was observed in mammal nests, ant hills, and dead wood (Table 3). There were also significant differences in the average abundance of Uropodina in the analysed merocenoses (Table 4). The Uropodine mites were less frequent in bird nests—they have not been found in >85 % of the analysed nests. The highest average number of Uropodina (>30 specimens) per sample is in ant hills, dead wood, and mammal nests.

Table 3.

Frequency and average number of Uropodina in soil and unstable microhabitats

| Soil | DW | TH | NM | NB | AH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of samples | 13,996 | 978 | 238 | 233 | 836 | 42 |

| Frequency of Uropodina (%) | 41.4 | 50.5 | 44.1 | 61.4 | 14.6 | 57.1 |

| Average no. of specimens per sample | 7.7 | 38.9 | 12.4 | 33.0 | 9.3 | 39.9 |

| 95 % confidence interval | 0.56 | 4.50 | 6.60 | 7.79 | 14.77 | 14.19 |

Soil soil and litter, DW dead wood, TH tree holes, NM mammal nests, NB bird nests, AH ant hills

Table 4.

Pairwise comparison of average abundance of Uropodina in the analysed merocenoses and soil

| Ant hills | Dead wood | Tree holes | Mammal nests | Bird nests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead wood | ns | ||||

| Tree holes | ns | ** | |||

| Mammal nests | ns | ns | *** | ||

| Bird nests | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Soil | * | *** | ns | *** | *** |

Kruskal–Wallis ranks ANOVA (H = 330.94, df = 5, P < 0.001; n = 16,341) followed by Dunn’s test: * 0.01 < P < 0.05; ** 0.001 < P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; ns not significant (P > 0.05)

The abundance of three most numerous species, i.e., Trachytes aegrota, Oodinychus ovalis, and Oodinychus karawaiewi, turned out to differ significantly in the analysed environments, but two other highly abundant species—Uroobovella pyriformis and Dinychus perforatus—were distributed evenly (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pairwise comparison of average abundance of the dominant species of Uropodina in soil and the analysed merocenoses

| Species | Comparisons | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 1–3 | 1–4 | 1–5 | 1–6 | 2–3 | 2–4 | 2–5 | 2–6 | 3–4 | 3–5 | 3–6 | 4–5 | 4–6 | 5–6 | |

|

T. aegrota H = 450.51 |

* | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ** | ns | *** | ns | ns |

|

Oo. ovalis H = 528.93 |

ns | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns |

|

Oo. karawaiewi H = 27.83 |

ns | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | *** | ** | ns | ns | ns |

|

Uro. pyriformis H = 16.2 |

ns | ns | ns | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

|

D. perforatus H = 8.38 |

ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Kruskal–Wallis ranks ANOVA (all species: df = 5, P < 0.001; n = 16,323) followed by Dunn’s test: * 0.01 < P < 0.05; ** 0.001 < P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; ns not significant (P > 0.05)

1 soil, 2 ant hills, 3 mammal nests, 4 bird nests, 5 dead wood, 6 tree holes

Dead wood

This microenvironment is inhabited by most species of Uropodina: 51 species (Table 2). The most numerous and frequent species was Oo. ovalis, the second most numerous species was Uro. pulchella (Table 6). These two species constituted about 75 % of the whole community. Metagynella carpatica is one of those extremely rare uropodine species in Poland, and it occurred only in dead wood.

Table 6.

Zoocenological analysis of dominance (classes D5-D1) and frequency (F5-F1) of the uropodine communities of the analysed merocenoses (see “Materials and methods” for a description of the classes)

| Dominance | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil and litter | |||

| D5—eudominants | 0 | F5—euconstants | 0 |

| D4—dominants | T. aegrota—28.89 % | F4—constants | T. aegrota—35.63 % |

| D3—subdominants | Ol. minima—13.20 % | F3—subconstants | Ol. minima—26.81 % |

| T. irenae—10.31 % | Ur. tecta—15.52 % | ||

| Oo. ovalis—8.42 % | T. pauperior—15.37 % | ||

| Oo. karawaiewi—7.18 % | F2—accesory species | Oo. ovalis—9.42 % | |

| D2—residents | T. pauperior—6.99 % | T. irenae—6.36 % | |

| D1—subresidents | 62 species | U. pannonica—5.54 % | |

| Din. perforatus—5.00 % | |||

| F1—accidents | 61 species | ||

| Dead wood | |||

| D5—eudominants | Oo. ovalis—56.38 % | F5—euconstants | 0 |

| D4—dominants | Uro. pulchella—18.60 % | F4—constants | Oo. ovalis—48.36 % |

| D3—subdominants | 0 | F3—subconstants | T. aegrota—20.45 % |

| D2—residents | T. aegrota—3.49 % | Uro. pulchella—16.87 % | |

| Dis. baloghi—3.05 % | F2—accesory species | Ol. minima—14.21 % | |

| D1—subresidents | 48 species | Din. carinatus—7.67 % | |

| Ur. tecta—5.11 % | |||

| F1—accidents | 46 species | ||

| Tree holes | |||

| D5—eudominants | 0 | F5—euconstants | 0 |

| D4—dominants | Oo. ovalis—23.66 % | F4—constants | Oo. ovalis—39.50 % |

| Uro. pyriformis—22.29 % | F3—subconstants | 0 | |

| D3—subdominants | Dis. baloghi—11.65 % | F2—accesory species | Uro. pyriformis—13.03 % |

| T. aegrota—9.69 % | Dis. baloghi—9.24 % | ||

| P. patavinus—7.47 % | T. aegrota—8.82 % | ||

| D2—residents | Din. carinatus—5.74 % | Din. carinatus—7.56 % | |

| Din. woelkei—3.56 % | Uro. pulchella—7.14 % | ||

| Uro. pulchella—3.17 % | Ur. tecta—5.88 % | ||

| D1—subresidents | 27 species | F1—accidents | 28 species |

| Mammal nests | |||

| D5—eudominants | Ph. borealis—41.96 % | F5—euconstants | 0 |

| D4—dominants | Ph. rackei—18.58 % | F4—constants | Ph. borealis—42.92 % |

| D3—subdominants | Ol. minima—8.71 % | Ph. rackei—36.48 % | |

| D2—residents | Ph. advena—6.76 % | F3—subconstants | N. brevinguiculata—25.75 % |

| Oo. karawaiewi—5.48 % | Oo. karawaiewi—21.89 % | ||

| N. brevinguiculata—5.26 % | Ol. minima—18.45 % | ||

| Oo. ovalis—4.25 % | F2—accesory species | Oo. ovalis—14.16 % | |

| D1—subresidents | 24 species | U. orbicularis—14.16 % | |

| Dis. modesta—8.58 % | |||

| Din. perforatus—8.15 % | |||

| F1—accidents | 22 species | ||

| Bird nests | |||

| D5—eudominants | O. orbicularis—35.89 % | F5—euconstants | 0 |

| D4—dominants | A. infirmus—18.85 % | F4—constants | 0 |

| Uro. pyriformis—17.94 % | F3—subconstants | 0 | |

| D3—subdominants | N. brevinguiculata—14.40 % | F2—accesory species | O. orbicularis—9.69 % |

| D2—residents | Al. flagelliger—3.84 % | A. infirmus—7.30 % | |

| U. orbicularis—3.02 % | N. brevinguiculata—5.98 % | ||

| D1—subresidents | 23 species | F1—accidents | 26 species |

| Ant hills | |||

| D5—eudominants | Oo. spatulifera—79.79 % | F5—euconstants | Oo. spatulifera—52.38 % |

| D4—dominants | 0 | F4—constants | 0 |

| D3—subdominants | Tr. coccinea—12.51 % | F3—subconstants | Tr. coccinea—16.67 % |

| D2—residents | Din. woelkei—3.67 % | F2—accesory species | Oo. ovalis—14.16 % |

| D1—subresidents | 9 species | Uro. pyriformis—9.52 % | |

| T. aegrota—7.14 % | |||

| F1—accidents | 7 species | ||

Tree holes

In tree holes from different tree species there were 34 species of Uropodina (Table 2). Similarly to dead wood, in the tree holes the most numerous and most frequent species was Oo. ovalis. Uro. pyriformis was slightly less numerous and frequent; three species (incl. Dis. baloghi) exceeded 55 % of the whole community (Table 6). Oplitis alophora, which is another very rare species in Poland, was found only in this microhabitat.

Mammal nests

Most of the analysed material comes from mole nests (Talpa europea). Thirty Uropodina species inhabited mammal nests (Table 2). The most frequent and numerous species were two species typical for this microhabitat, Ph. borealis and Ph. rackei; they constituted ca. 60 % of the entire community. Phaulodiaspis rackei could be also accidentally found in soil. Moreover, N. breviunguiculata, Oo. karawaiewi and Ol. minima were also frequent, but less numerous. Uros. hunzikeri, which is a very rare species, was found in the mole nests.

Bird nests

In the nests of almost 30 bird species (Błoszyk et al. 2006a), 28 species of Uropodina were found (Table 2). L. orbicularis was preponderant in the community, but also A. infirmus, Uro. pyriformis, and N. breviunguiculata were quite numerous (Table 6). These four species constituted >87 % of the community. However, the frequency of these species was low and did not exceed 10 %. The species found only in bird nests is N. floralis.

Ant hills

In the material from the ant hills (Formica s.l.), 12 uropodine species were found (Table 2). The most numerous (80 %) and most frequent (52 %) species was Oo. spatulifera. Also Tr. coccinea and Oo. ovalis occurred apparently frequently (Table 6).

Role of merocenoses in ecosystem biodiversity

Table 7 shows the communities of Uropodina found in mole nests and in the soil samples, on the same meadow, near Jarocin (Wielkopolska). Out of the 11 species found in the mole nests, the two most dominant species (Ph. rackei and Ph. borealis) were not found in the soil. Morover, six species from the soil were not found in the nests. The average number of mites per sample volume was 30 times higher in the nests than in the soil. The frequency of all species occurring in both environments was always higher in the mole nests.

Table 7.

Dominancy (D%) and frequency (F%) of Uropodina in mole nests and in soil of one meadow in Jarocin (Wielkopolska)

| Species | Nests | Soil | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | D% | F% | Total | D% | F% | |

| Ph. rackei | 360 | 39.52 | 32.35 | |||

| Ph. borealis | 302 | 33.15 | 44.12 | |||

| Ol. minima | 68 | 7.46 | 35.29 | 29 | 25.89 | 10.40 |

| N. breviunguiculata | 54 | 5.93 | 11.76 | 39 | 34.82 | 12.00 |

| Oo. ovalis | 48 | 5.27 | 20.59 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 |

| Oo. karawaiewi | 27 | 2.96 | 26.47 | 18 | 16.07 | 5.60 |

| Din. perforatus | 21 | 2.31 | 8.82 | 2 | 1.79 | 1.60 |

| Uro. orbicularis | 20 | 2.20 | 5.88 | 4 | 3.57 | 3.20 |

| Din. carinatus | 6 | 0.66 | 5.88 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 |

| Dis. modesta | 4 | 0.44 | 5.88 | 8 | 7.14 | 2.40 |

| Ur. tecta | 1 | 0.11 | 2.94 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 |

| Cilliba rafalskii | 2 | 1.79 | 0.80 | |||

| Din. inermis | 3 | 2.68 | 2.40 | |||

| Ne. splendida | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 | |||

| Pr. punctatus | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 | |||

| T. aegrota | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 | |||

| Ur. pannonica | 1 | 0.89 | 0.80 | |||

| Total | 911 | 112 | ||||

| Average no. of specimens per sample | 26.79 | 0.90 | ||||

| No. of samples | 34 | 125 | ||||

In the 1,259 samples (407 from dead wood, 852 from soil and litter of horn-beam forests) collected in the three nature reserves in Wielkopolska, 33 species of Uropodina were found: 28 species in dead wood and 20 species in soil and litter (Table 8). Five species of Uropodina could be identified as typical soil species (I. penicillata, Ol. misella, Ps. calcarata, Ur. pannonica, Uro. orbicularis), whereas 13 species (Uro. obovata, A. infirmus, Tre. elegans, Din. arcuatus, L. orbicularis, Tr. coccinea, Pseudouropoda sp., P. cylindricus, Ps. tuberosa, C. erlangensis, Dis. baloghi, N. breviunguiculata, and N. stylifera) were found only in the material from the dead wood (Table 8). Only 15 species were present in both environments. The mite communities inhabiting dead wood or soil and litter had a different structure of dominancy. In the analysed soil and litter, the most numerous species were T. aegrota and Ol. minima, whereas in the dead wood Oo. ovalis and Uro. pulchella were more numerous and frequent. In both environments the specimens of these species constituted >50 % of the whole community.

Table 8.

Dominancy (D%) and frequency (F%) of Uropodina in dead wood and soil and litter samples of horn-beam forests from natural reserves in Wielkopolska

| Species | Dead wood | Soil and litter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | D% | F% | Total | D% | F% | |

| Oo. ovalis | 2,806 | 71.29 | 56.51 | 915 | 22.25 | 27.11 |

| Uro. pulchella | 235 | 5.97 | 11.55 | 13 | 0.32 | 0.94 |

| Ol. minima | 203 | 5.16 | 14.00 | 917 | 22.30 | 32.04 |

| Din. woelkiei | 177 | 4.50 | 6.39 | 19 | 0.46 | 0.35 |

| T. aegrota | 172 | 4.37 | 16.71 | 1,184 | 28.79 | 38.97 |

| Din. carinatus | 101 | 2.57 | 7.13 | 9 | 0.22 | 0.82 |

| Ur. tecta | 74 | 1.88 | 6.88 | 874 | 21.25 | 34.39 |

| T. pauperior | 26 | 0.66 | 3.69 | 61 | 1.48 | 2.46 |

| A. infirmus | 25 | 0.64 | 0.49 | |||

| Po. sansonei | 18 | 0.46 | 1.23 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| Uro. obovata | 16 | 0.41 | 0.98 | |||

| Tre. elegans | 14 | 0.36 | 1.97 | |||

| Din. arcuatus | 12 | 0.30 | 1.47 | |||

| Din. perforatus | 11 | 0.28 | 1.47 | 3 | 0.07 | 0.35 |

| C. rafalskii | 9 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 44 | 1.07 | 2.00 |

| Din. sp. | 8 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 8 | 0.19 | 0.82 |

| L. orbicularis | 7 | 0.18 | 1.23 | |||

| C. cassideasimilis | 7 | 0.18 | 0.74 | 17 | 0.41 | 0.82 |

| Tr. coccinea | 4 | 0.10 | 0.25 | |||

| Pseudouropoda sp. | 3 | 0.08 | 0.74 | |||

| P. cylindricus | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |||

| Ps. tuberosa | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |||

| C. erlangensis | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |||

| Uro. pyriformis | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| D. cordieri | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.47 |

| Dis. baloghi | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |||

| N. breviunguiculata | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |||

| N. stylifera | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |||

| I. penicillata | 1 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |||

| Ol. misella | 2 | 0.05 | 0.12 | |||

| Ps. calcarata | 1 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |||

| Ur. pannonica | 31 | 0.75 | 2.35 | |||

| Uro. orbicularis | 2 | 0.05 | 0.12 | |||

| Total | 3,936 | 4,113 | ||||

| Average no. of specimens per sample | 9.67 | 4.83 | ||||

| No. of samples | 407 | 852 | ||||

Bold—dominat species

Five out of the seven most numerous species (Oo. ovalis, T. aegrota, Ol. minima, Uro. pulchella, and Ur. tecta) in both environments revealed a significant preference for each of the two types of environments (i.e., occurred more numerously; Table 9). The abundance of the uropodine mites in the samples from the dead wood is much (2 times) higher than in the soil samples.

Table 9.

Mean (±SE) abundance of the seven most dominant Uropodina species in soil and dead wood in the three nature reserves of Wielkopolska

| Species | Dead wood | Soil and litter | za | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. aegrota | 2.46 ± 2.86 | 3.57 ± 6.15 | 6.71 | <0.001 |

| T. pauperior | 1.73 ± 0.70 | 2.91 ± 4.60 | 0.35 | >0.05 |

| Oo. ovalis | 12.20 ± 20.44 | 3.96 ± 6.51 | 10.33 | <0.001 |

| U. tecta | 2.64 ± 3.05 | 2.98 ± 5.39 | 7.91 | <0.001 |

| Ol. minima | 3.56 ± 4.09 | 3.36 ± 3.71 | 5.17 | <0.001 |

| Uro. pulchella | 5.00 ± 5.93 | 1.63 ± 1.06 | 3.06 | <0.01 |

| D. woelkei | 6.81 ± 9.46 | 6.33 ± 7.51 | 1.73 | >0.05 |

aMann–Whitney U test

Discussion

Błoszyk et al. have emphasized many times the specificity of Uropodina communities (Błoszyk and Olszanowski 1986; Błoszyk and Miko 1990; Błoszyk and Athias-Binche 1998; Błoszyk 1999; Błoszyk and Bajaczyk 1999; Skoracka et al. 2001; Bloszyk et al. 2003a, b, 2005a, 2006a; Bajerlein et al. 2006; Błoszyk and Gwiazdowicz 2006, and Gwiazdowicz et al. 2006). Also other researchers have provided cogent evidence for the specificity of zoocenoses of Uropodina in such microhabitats (e.g. Athias-Binche 1977a, b; Krištofík et al. 1993; Gwiazdowicz et al. 2000; Gwiazdowicz and Sznajdrowski 2000; Mašán 2001; Gwiazdowicz and Klemt 2004; Gwiazdowicz and Kmita 2004).

The uropodine species found in the soil and litter contain 92 % of all species found in Poland (Napierała 2008). The most characteristic feature of the uropodine mite communities inhabiting unstable microhabitats (such as dead wood, tree holes, mammal and bird nests, and ant hills) is not only their specific species composition but also their dominancy structure. The species composition differed among the merocenoses, more than in the communities occurring in soil and litter of different forest types. In each type of merocenose one or two of the dominant species constituted >50 % of the entire community, and some species were typical for a particular type (Uro. pyriformis, Ph. borealis, Ph. rackei, Oo. spatulifera, and Tr. coccinea). Instead of strong predomination of one species, soil communities often have a group of 4–5 species, which constitute their ‘core’. These are often the same species in each case, i.e., T. aegrota, Ol. minima, Ur. tecta, Oo. ovalis, and Oo. karawaiewi.

Uropodina species associated with soil and unstable microhabitats differ as to their reproductive strategies (Błoszyk and Olszanowski 1985a, b; Błoszyk 1999; Błoszyk et al. 2004). Communities of Uropodina inhabiting soil and litter are usually predominated by species which reproduce parthenogenetically (thelytoky) (e.g. T. aegrota, Ur. tecta, and Ol. minima), whereas in merocenoses bisexual species prevail (e.g. Oo. ovalis, and Din. woelkei). The only exception is Uro. pulchella, which is one of the most numerous species in dead wood, but it reproduces parthgenogenetically (male-to-female ratio 1:15) (Błoszyk et al. 2004). In this case, the number of the males rises proportionally to the increase of the population size (Błoszyk, unpublished data). For most of soil-inhabiting Uropodina (such species as T. aegrota, T. pauperior, T. lamda, Ol. minima, U. orbicularis), males are observed sporadically (Błoszyk and Olszanowski 1985b; Błoszyk 1999; Błoszyk et al. 2004, 2005b).

Uropodina species from soil and unstable microhabitats also have different modes of dispersion. The small size of merocenoses, their inconstancy, isolation and fragmentation compel such species to develop special ways of dispersion which will enable them to leave a disappearing habitat and find a new one. For most uropodine species passive dispersion between microhabitats is phoresy (Athias-Binche 1993, 1994; Błoszyk 1999; Bajerlein and Błoszyk 2004; Bajerlein et al. 2006; Błoszyk et al. 2006b). Soil, which is a more stable and homogenous environment, enables existence of a population consisting of clones of the paternal specimens, whereas unstable merocenose requires continual genetic recombination. The very low abundance of Uropodina in soil and problems in finding a sexual partner, force these mites to reproduce parthenogenetically (Błoszyk et al. 2004, 2005b).

The studies on the structure of Uropodina communities in merocenoses are important because they may shed new light on the issues concerning species composition of Uropodina in Europe after the regression of the last glaciation. Furthermore, merocenoses constitute ‘halts’ for the populations of many species, forming stepping stones in their dispersion. It is also possible that many Uropodina species have migrated from the South to the North of Europe because they were carried there by arthropods, birds, and mammals when the glacier regressed, and then they had to inhabit merocenoses. The colonization of soil and litter probably took place much later.

Unstable microhabitats enrich the overall biodiversity of forest and meadow ecosystems. Dead wood is one of the most important components in preserving biological diversity of forest ecosystems (Gutowski et al. 2002). The number of species that form Uropodina communities is proportional to the range and the number of microhabitats in a particular ecosystem. The presence of merocenoses increases the general biodiversity of an ecosystem—not only of Uropodina—therefore, it is important to protect them, e.g. by not removing dead wood from forests, not bricking up tree hollows, and leaving ant hills undisturbed.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a result of a project supported from KBN—Research Project NN 304 3400 33, NCN—Research Project N N304 070740 and 2/216/WI/09 AR-UAM).

References

- Athias-Binche F. Étude quantitative des Uropodides édaphiques de la hêtraie de la Tillaie en forêt be Fontainebleu (Acarines; Anactinotriches) Rev Écol Biol Sol. 1977;15(1):67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F (1977b) Étude quantitative des Uropodides (Araneis; Anactinotriches) d’un arbre mort de la hetraie de la Zassane. 1—Caratéres généraux du peuplement. Vie Milieu 27(2):157–175

- Athias-Binche F. Effects of some soil features on a Uropodine mite community in the Massane forest (Parenees-Orientales, France) In: Rodriguez JG, editor. Recent advances acarology. London: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 567–573. [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F. Ęcologie des Uropodides édaphiques (Arachnides, Parasitoformes) des trois écosystèmes forestiers. 3. Abondance et biomasse des microarthropodes du sol, facteurs du milieu, abondance et distribution spatiale des Uropodides. Vie Milieu. 1982;32:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F. Écologie des Uropodides édaphiques (Arachnides: Parasitiformes) des trois écosystèmes forestiers. 4. Abondance, biomasse, distribution verticale, sténo-et eurytopie. Vie Milieu. 1982;32:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F. Écologie des Uropodides édaphiques (Arachnides: Parasitiformes) de trois écosystèmes forestiers. 5. Affinités interspécifiques, divérsite, structures écologiques et quantitatives des peuplements. Vie Milieu. 1983;33:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F. La phorésie chez les acariens uropodides (Anactinotriches), une stratégie écologique originale. Acta Oecol Oecol Gen. 1984;5:119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F. Dispersal in varying environments: the case of phoretic uropodid mites. Can J Zool. 1993;71:1793–1798. doi: 10.1139/z93-255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Athias-Binche F (1994) La phorésie chez les acariens. Aspects adaptatifs et évolutifs. Editions du Castillet, Perpignan, p 178

- Athias-Binche F, Habersaat U. An ecological study of Janetiella pyriformis (Berlese, 1920), a phoretic Uropodina from decomposing organic matter (Acari: Anactinotrichida) Mitt Schweiz Entomol Ges. 1988;61:377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Bajerlein D, Błoszyk J. Phoresy of Uropoda orbicularis (Acari: Mesostigmata) by beetles (Coleoptera) associated with catlle dung in Poland. Eur J Entomol. 2004;101:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bajerlein D, Błoszyk J, Gwiazdowicz D, Ptaszyk J, Halliday RB. Community structure and dispersal of mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) in nests of the white stork (Ciconia ciconia) Biologia Bratyslava. 2006;61(5):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J. Rodzaj Trachytes Michael, 1894 (Acari: Mesostigmata) w Polsce. Pr Kom Biol PTPN. 1980;54:5–52. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J (1983) Uropodina Polski (Acari: Mesostigmata). PhD Dissertation. Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań

- Błoszyk J (1985) Materiały do znajomości roztoczy gniazd kreta (Talpa europaea L.). I. Uropodina (Acari, Mesostigmata). Przegl. Zool 29(2):171–177

- Błoszyk J (1990) Fauna Uropodina (Acari:Mesostigmata) spróchniałych pni drzew i dziupli w Polsce. Zeszyty Probl. Postepow Nauk Roln. Warszawa 373:217–235

- Błoszyk J (1992) Materiały do znajomości akarofauny Roztocza. III. Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata). Fragm. Faunistic 35(20):323–344

- Błoszyk J (1999) Geograficzne i ekologiczne zróżnicowanie zgrupowań roztoczy z kohorty Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) w Polsce. I. Uropodina lasów grądowych (Carpinion betuli). Wydawnictwo Kontekst. Poznań 246

- Błoszyk J, Athias-Binche F. Survey of European mites of cohort Uropodina. I. Geographical distribution, biology and ecology of Polyaspinus cylindricus Berlese, 1916. Biol Bull Poznań Zool. 1998;32:89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Bajaczyk R (1999) The firs record of Phaulodinychus borealis (Sellnick, 1949) phoresy (Acari: Uropodina) associated with fleas (Siphonaptera) in mole nests. In: Soil zoology in Central Europe, pp 13–17

- Błoszyk J, Gwiazdowicz DJ. Acarofauna of nests of the White Stork Ciconia ciconia, with special attention to mesostigmatid mites. In: Tryjanowski P, Sparks TH, Jerzak L, editors. The white stork in Poland: studies in biology, ecology and conservation. Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe; 2006. pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Miko L (1990) Podna Dauna Pienin. I. Uropodina (Acari: Anactinotrichida). Entomologicke Problemy XX:21–47

- Błoszyk J, Olszanowski Z (1985a) Materiały do znajomości roztoczy gniazd i budek lęgowych ptaków. I. Uropodina i Nothroidea (Acari: Mesostigmata et Oribatida). Przegl Zool 29(1):69–74

- Błoszyk J, Olszanowski Z (1985b) Rodzaj Trachytes Michael, 1894 (Acari, Mesostigmata) w Polsce. III. Sporadyczne występowanie samców w populacjach niektórych partenogenetycznych gatunków. Przegl Zool 29(3):313–316

- Błoszyk J, Olszanowski Z (1986) Materiały do znajomości fauny roztoczy gniazd i budek lęgowych ptaków. II. Różnice w liczebności i składzie gatunkowym populacji Uropodina (Acari: Anactodotrichida) budek lęgowych na Mierzeji Wiślanej na podstawie dwuletnich obserwacji. Przegl Zool 30(1):63–66

- Błoszyk J, Bajerlein D, Skoracka A, Bajaczyk R (2001) Uropoda orbicularis (Muller, 1776) (Acari: Uropodina) as an example of a mite adapted to synanthropic habitats. In: Tayovsky K, Pizl V (eds) Proceedings of 6th CEWSZ, ISB AS CR. 2002: studies on Soil Fauna in Central Europe. Tisk Josef Posekany, Czeskie Budziejowice, pp 7–11

- Błoszyk J, Bajaczyk R, Markowicz M, Gulvik M. Geographical and ecological variability of mites of the suborder Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) in Europe. Biol Lett. 2003;40(1):15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Napierała A, Markowicz-Rucińska M. Zróżnicowanie zgrupowań Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigamata) wybranych rezerwatów Wielkopolski. Parki nar Rez przyr. 2003;22:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Adamski Z, Napierała A, Zawada M. Parthenogenesis as a life strategy among mites from the suborder Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) Can J Zool. 2004;82(9):1503–1511. doi: 10.1139/z04-133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Bajerlein D, Gwiazdowicz D, Halliday RB. Nests of the white stork Ciconia ciconia (L.) as habitat for mesostigmatic mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) Acta Parasitol. 2005;50(2):171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Napierała A, Dylewska M, Bajaczyk R (2005b) Phenomenon of parthenogenesis among mites from suborder Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata). Advances in Polish Acarology. SGGW, Warszawa, pp 15–25

- Błoszyk J, Bajerlein D, Gwiazdowicz DJ, Halliday RB, Dylewska M. Uropodina mites communities (Acari: Mesostigmata) in birds’ nests in Poland. Belgian J Zool. 2006;136(2):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Błoszyk J, Klimczak J, Leśniewska M. Phoretic relationships between Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) and centipedes (Chilopoda) as an example of evolutionary adaptation of mites to temporary microhabitats. Eur J Entomol. 2006;103:699–707. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GO, Till WM. Mesostigmatic mites of Britain and Ireland (Chelicerata: Acari-Parasitiformes). An introduction to their external morphology and classification. Trans Zool Soc Lond. 1979;35:139–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1979.tb00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faasch H. Beitrag zur Biologie der einheimischen Uropodiden Uroobovella marginata (C. L. Koch 1839) und Uropoda orbicularis (O. F. Müller 1776) und experimentelle Analyse ihres Phoresieverhaltens. Zool Jb Syst Bd. 1967;94:521–608. [Google Scholar]

- Gutowski JM, Bobiec A, Pawlaczyk P, Zub K (2002) Po co nam martwe drzewa? Wydawnictwo Lubuskiego Klubu Przyrodników, Świebodzin. 63 ss

- Gwiazdowicz DJ, Klemt J. Mesostigmatic mites (Acari, Gamasida) in selected microhabitats of the Biebrza National Park (NE Poland) Biol Lett. 2004;41(1):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazdowicz DJ, Kmita M (2004) Mites (Acari, Mesostigmata) from selected microhabitats of the Ujście Warty National Park. Acta Sci. Pol. Silv. Colendar Rat Ind Lignar 3(2):49–55

- Gwiazdowicz DJ, Sznajdrowski R (2000) Mites (Acari, Gamasida) from selected microhabitats of Bieszczady National Park. In: Materiały z XXVI Sympozjum akarologicznego ‘Akarologia polska u progu Nowego Tysiąclecia’ Kazimierz Dolny, 24–26 października 1999r, pp 98–110

- Gwiazdowicz DJ, Mizera T, Skorupski M. Mites (Acari, Gamasida) from the nests of birds of prey in Poland. Buteo. 2000;11:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazdowicz D, Błoszyk J, Mizera T, Tryjanowski P. Mesostigmatic mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) in White-Tailed sea eagle nests (Heliaeetus albicilla) J Raptor Res. 2005;39(1):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazdowicz DJ, Błoszyk J, Bajerlein D, Halliday RB, Mizera T. Mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) inhabiting nests of the white-tailed sea eagle Heliaetus albicilla (L.) in Poland. Entomol Fennica. 2006;17:366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Huţu M. Structura comunitatilor de Uropodide (Acarina: Anactinotrichida) din zona montilor retezant. Parcul National Retezat. In: Popovici I, editor. Studii ecologice. Brasov: West Side Comuters; 1993. pp. 238–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kadite A, Petrova D. Kohorta Uropodina, family Uropodida. In: Giljarova MS, Bregetova NG, editors. Opredelitiet obitajuih v povie kleej Mesostigmat Naauka. Russia: Leningrad; 1977. pp. 32–690. [Google Scholar]

- Karg W. Acari (Acarina), Milben Unterordnung Parasitiformes (Anactinochaeta) Uropodina Kramer, Schildkrautenmilben. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Krištofík J, Mašán P, Šustek Z, Gajdoš P. Arthropods in the nests of penduline tit (Remiz pendulinus) Biol Bratislava. 1993;48:493–505. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE. Measuring biological diversity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mašán P (2001) Mites of the cohort Uropodina (Acarina, Mesostigmata) in Slovakia. Ann Zool Botan 223–320

- Napierała A (2008) Struktura zgrupowań i rozkład przestrzenny Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) w wybranych kompleksach leśnych Wielkopolski. PhD Dissertation. Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań

- Napierała A, Błoszyk J, Bruin J. Communities of uropodine mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) in selected oak-hornbeam forests of the Wielkopolska region (Poland) Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;49:291–303. doi: 10.1007/s10493-009-9262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoracka A, Skoracki M, Błoszyk J, Stachowiak M (2001) The structure of dominance and frequency of Mesostigmata (Acari) in compost. In: Tayovsky K, Pizl V (eds) Proceedings of 6th CEWSZ, ISB AS CR. 2002: studies on Soil Fauna in Central Europe. Tisk Josef Posekany, Czeskie Budziejowice, pp 169–175