Abstract

Neuroprotective therapies based on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) administration have been proposed for Huntington's disease (HD) treatment. However, our group has recently reported reduced levels of TrkB in HD mouse models and HD human brain suggesting that besides a decrease on BDNF levels a reduction of TrkB expression could also contribute to diminished neurotrophic support in HD. BDNF can also bind to p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) modulating TrkB signaling. Therefore, in this study we have analyzed the levels of p75NTR in several HD models, as well as in HD human brain. Our data demonstrates a p75NTR/TrkB imbalance in the striatum of two different HD mouse models, HdhQ111/111 homozygous knockin mice and R6/1 mice that was also manifested in the putamen of HD patients. The imbalance between TrkB and p75NTR levels in a HD cellular model did not affect BDNF-mediated TrkB activation of prosurvival pathways but induced activation of apoptotic cascades as demonstrated by increased JNK phosphorylation. Moreover, BDNF failed to protect mutant huntingtin striatal cells transfected with p75NTR against NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity, which was associated with decreased Akt phosphorylation. Interestingly, lack of Akt activation following BDNF and NMDA treatment correlated with increased PP1 levels. Accordingly, pharmacological inhibition of PP1 by okadaic acid (OA) prevented mutant huntingtin striatal cell death induced by NMDA and BDNF. Altogether, our findings demonstrate that the p75NTR/TrkB imbalance induced by mutant huntingtin in striatal cells associated with the aberrant activity of PP1 disturbs BDNF neuroprotection likely contributing to increasing striatal vulnerability in HD. On the basis of this data we hypothesize that normalization of p75NTR and/or TrkB expression or their signaling will improve BDNF neuroprotective therapies in HD.

Keywords: BDNF receptors, excitotoxicity, huntingtin, neurodegeneration, neuroprotection

Deficits of neurotrophic support caused by reduced levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been implicated in the selective vulnerability of striatal neurons in Huntington's disease (HD).1 Neuroprotective therapies based on BDNF administration have been proposed to slow or prevent the HD disease progression. However, the effectiveness of BDNF may depend on the proper expression of its neuronal receptor TrkB. Indeed, reduced striatal TrkB expression has been reported in knockin HD cellular and mouse models, exon-1 HD transgenic mice and HD human brain,2, 3, 4 which suggests that mutant huntingtin could lead to reduced neurotrophic support not only by altering BDNF levels but also by affecting TrkB expression. This scenario can still be more complex as BDNF also binds to p75NTR a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily.5 In contrast to Trk receptors, which have a well-defined trophic role, p75NTR may promote a variety of complex and sometimes opposing functions ranging from trophism to apoptosis depending on the cellular context and coexpression with Trk receptors.6, 7 Thus, p75NTR can either potentiate or reduce neurotrophic Trk receptor function or act independently to induce apoptotic signaling cascades.5, 8, 9 In the adult brain, p75NTR expression is downregulated in most brain areas.10, 11 However, in damaged or diseased conditions p75NTR expression is rapidly induced, which has been associated with neuronal cell death.7, 12 Thus, in neonatal mice brain, NMDA-induced injury is associated with upregulation of p75NTR13, 14 while in rats excitotoxicity induced by kainate administration causes an increase on p75NTR levels accompanied by a significant cell death.15 Importantly, in HD, striatal neurons are selectively vulnerable to glutamate-induced neurotoxicity suggesting that excitotoxicity has an important role in HD striatal neurodegeneration.16 In this view, Zuccato et al. have demonstrated increased p75NTR but reduced TrkB mRNA expression in the caudate but not in the cortex of HD patients4 while impaired TrkB-mediated ERK1/2 activation was recently reported by our group in HD striatal cell lines.3 Altogether, this data suggest that neurotrophic deficits in HD could account not only for BDNF reduction but also for an imbalance between TrkB and p75NTR-mediated cell signaling. To test this hypothesis we have analyzed the levels of p75NTR and TrkB in the striatum of two distinct HD mouse models at different HD pathological stages, as well as in the putamen of HD patients. We found an imbalance between p75NTR and TrkB levels that was associated with a reduction of BDNF-mediated neuroprotection against NMDA excitotoxicity. Altogether, our findings support the idea that normalization of TrkB and p75NTR protein levels or their functional signaling cross-talk would be a major step to improve neuroprotective therapies with BDNF in HD.

Results

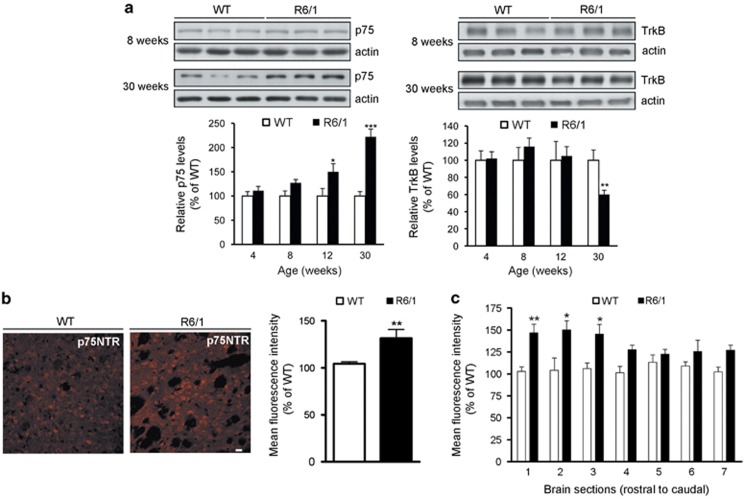

p75NTR and TrkB protein levels are altered in the striatum of R6/1 mice

Reduced BDNF neuroprotection contributes to striatal vulnerability in HD.17 Given that BDNF effects can be mediated by TrkB and p75NTR we analyzed the expression of these receptors in the striatum of wild-type and mutant huntingtin R6/1 mice at different HD pathological stages (Figure 1a). p75NTR protein levels were significantly increased in the striatum of R6/1 mice at 12 weeks of age (∼50%) an increase that was even more evident at 30 weeks (∼120%) revealing an effect of age and genotype on changes in p75NTR (F(3,18)=4.133; P<0.05). By contrast, a significant reduction of TrkB was found in R6/1 only at late disease stages (∼40%). As we described that reduced TrkB was associated with decreased TrkB transcription2 we examined whether increased p75NTR mRNA expression could account for upregulation of p75NTR protein levels. A significant increase in p75NTR mRNA was found in the striatum of R6/1 mice at 30 weeks of age (WT:1.0±0.3 and R6/1:2.3±0.4, P<0.05) indicating that both p75NTR mRNA and protein are increased in R6/1 mice. To further evaluate the expression and distribution of p75NTR immunohistochemistry analysis was performed in striatal slices from wild-type and R6/1 mice at 30 weeks of age (Figure 1b). According to the biochemical data a significant increase (∼30%) on p75NTR staining was revealed in mutant compared with wild-type mice. As striatal neuronal loss has a characteristic rostro-caudal gradient of pathological damage,18 p75NTR levels were analyzed on coronal sections across the rostro-caudal extension of the striatum (Figure 1c). Significant differences were detected along the rostro-caudal striatum with the rostral sections having significantly more p75NTR staining, which suggest a correlation between p75NTR levels and striatal atrophy.

Figure 1.

Imbalance between p75NTR and TrkB expression in the striatum of R6/1 mice. (a) Representative immunoblots showing the levels of p75NTR, TrkB and β-actin as a loading control in striatal extracts obtained from WT and R6/1 mice at 8 and 30 weeks of age. The histograms represent the relative levels of p75NTR and TrkB expressed as percentage of wild-type values. Values are given as mean±S.E.M. of 5–6 independent samples. Data was analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Student's t-test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 respect to wild-type mice. (b) Representative immunohistochemical images depicting levels of p75NTR staining in the striatum of WT and R6/1 mice at 30 weeks of age. The histogram represents the mean fluorescence intensity of p75NTR (mean±S.E.M., n=3) expressed as percentage of wild-type levels. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test **P<0.01 respect to wild-type mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) The histogram represents the mean fluorescence intensity of p75NTR staining along rostral to caudal striatal sections from WT and R6/1 mice at 30 weeks of age expressed as percentage of wild-type values (mean±S.E.M. n=3). Data was analyzed by Student's t-test *P<0.05; **P<0.01 respect to wild-type mice

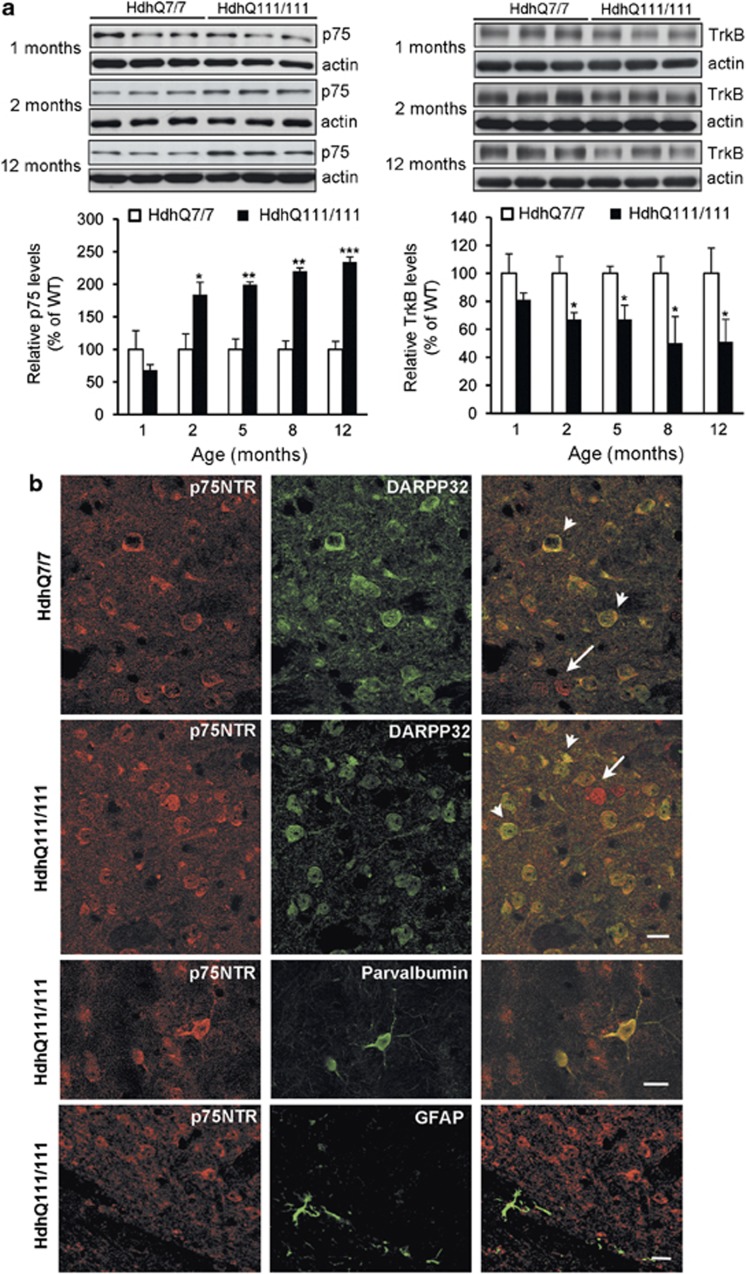

Knockin HdhQ111/111 mutant mice also display p75NTR/TrkB imbalance in the striatum

We next analyzed whether in a different HD mouse model expressing endogenous levels of full-length mutant huntingtin (HdhQ111/111) the expression of both receptors was also altered. No significant differences on p75NTR levels between wild-type and mutant mice were found at 1 month of age while a significant increase was evident at 2 months (∼80%), 5 and 8 months (∼90%) and 12 months of age (∼135%) (Figure 2a). Similar to that observed in R6/1 mice the increase on p75NTR was (1) progressive, starting at 2 months of age and worsening thereafter (F(4,32)=7,415; P<0.001) and (2) associated with upregulation of p75NTR mRNA expression (HdhQ7/7:1.0±0.1 and HdhQ111/111:1.8±0.3, P<0.05). When TrkB levels were examined we found a significant decrease (∼40%) at early HD stages that was sustained along the disease progression (Figure 2a). Given that p75NTR can be upregulated by neurons or glia19 double immunostaining for p75NTR, DARPP32 and parvalbumin as GABAergic striatal neuronal markers and GFAP as astroglial marker was performed (Figure 2b). Confocal analysis revealed that the majority of DARPP32-positive cells were also positive for p75NTR indicating a neuronal distribution of p75NTR. We also observed p75NTR-positive cells that were negative for DARPP32 that could correspond to parvalbumin interneurons. Double immunolabeling confirm colocalization between p75NTR and parvalbumin indicating that p75NTR was also localized in these GABAergic interneurons. Importantly, p75NTR immunoreactivity failed to colocalize with GFAP demonstrating that p75NTR was not detectable in astrocytes.

Figure 2.

p75NTR and TrkB protein levels are also modified in the striatum of full-length HdhQ111/111 mutant mice. (a) Representative immunoblots showing the levels of p75NTR, TrkB and β-actin as a loading control in striatal extracts obtained from wild-type HdhQ7/7 and mutant HdhQ111/111 mice at 1, 2 and 12 months of age. The histograms represent the relative levels of p75NTR and TrkB expressed as percentage of wild-type values. Values are given as mean±S.E.M. of 5–6 independent samples. Data was analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Student's t-test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 respect to wild-type mice. (b) (Upper panel) double immunostaining showing p75NTR and DARPP32 in the striatum of wild-type (HdhQ7/7) and mutant (HdhQ111/Q111) mice at 12 months of age. Some cells are single-labeled for p75NTR (arrows), whereas a high proportion of cells are double-labeled for p75NTR and DARPP32 in both wild-type and HD mutant mice (arrowheads). (Middle panel) double immunostaining showing p75NTR and parvalbumine staining in the striatum of mutant HdhQ111/111 mice at 12 months of age. Most of the parvalbumine-positive neurons are also positive for p75NTR. (Bottom panel) Double immunostaining showing p75NTR and GFAP in the striatum of mutant (HdhQ111/111) mice at 12 months of age. p75NTR and GFAP immunoreactivity demonstrates lack of colocalization. Scale Bar, 25 μm

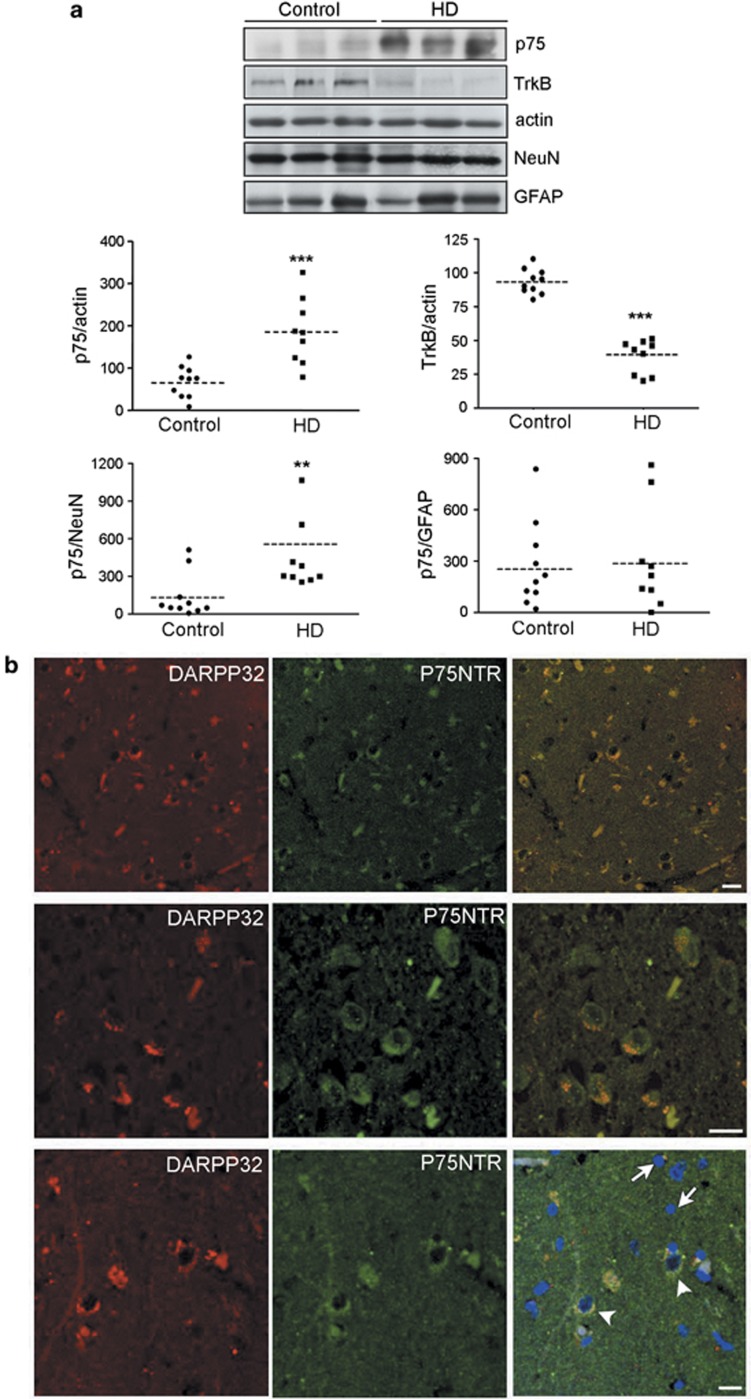

Changes on p75NTR and TrkB protein levels are manifested in the putamen of HD patients

Next we analyzed whether aberrant p75NTR and TrkB protein levels were recapitulated in HD human brain. Upon normalization to actin we found in HD samples a significant increase in p75NTR (∼100%) together with a decrease in TrkB (∼60%) levels compared with control samples (Figure 3a). The levels of p75NTR were also normalized to NeuN and GFAP. Normalization to GFAP yielded no significant changes compared with control samples while a significant increase was found when normalized to NeuN (∼300%). To further confirm the neuronal distribution of p75NTR in HD human brain double immunolabeling for p75NTR and DARPP32 was performed in HD caudate-putamen brain sections. Confocal analysis demonstrated colocalization of p75NTR and DARPP32 revealing that p75NTR is primary neuronal in HD human brain, which agrees with our immunohistochemistry data in knockin HD mutant mice. Consistently, glia cells indentified by DAPI staining as cells with bright and condensed nuclei were negative for p75NTR immunostaining.

Figure 3.

The putamen of HD patients shows altered p75NTR and TrkB protein levels. (a) Human brain tissue from 10 control and 9 HD cases were analyzed by western blot. Immunoblots were probed with p75NTR, TrkB, β-actin as loading control and NeuN and GFAP as neuronal and astroglial markers, respectively. Scatter plots display the relative levels of p75NTR and TrkB normalized to actin, NeuN or GFAP. The horizontal line represents the normalized mean value in control and HD subjects. Data was analyzed using Student's t-test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with control. (b) Immunohistochemistry in caudate-putamen of HD brain (Vonsatel grade 1) showing extensive colocalization between DARPP32 (striatal neuronal marker) and p75NTR. Nuclear staining was revealed by DAPI labeling to show that glia cells (arrows) are not positive for p75NTR in contrast to neuronal cells (arrowheads). Scale bar, 10 μm

BDNF treatment reduces the cell survival of corticostriatal slices from knockin HdhQ111/111 mutant mice

Given the importance of TrkB to mediate BDNF neuroprotection we analyzed whether the p75NTR/TrkB imbalance in HD might influence BDNF-induced cell survival. To this aim adeno-associated viruses (AAV) expressing p75 shRNA or scramble shRNA were bilaterally injected into the striatum of wild-type and HD mice, corticostriatal slices obtained and cell survival analyzed following BDNF treatment (Figure 4). First, we examined viability of tissue slices by fluorescence microscopy using calcein as a vital dye and propidium iodide as a marker for cell death. An optimal preservation of slices as judged from the cell viability achieved was found (Supplementary Figure S1a). Then we analyzed the efficiency of AAV-p75shRNA to knockdown p75NTR. Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant reduction of p75NTR in wild-type and mutant corticostriatal slices (∼50% and 40%, respectively; P<0.05). Histological analysis by confocal microscopy further confirmed lack of p75NTR expression in neurons transduced with p75shRNA (Figure 4a). Finally, cell survival was evaluated in BDNF-treated slices (Figure 4b). BDNF incubation increased the cell survival of wild-type corticostriatal slices (∼40%) while a significant reduction was found in HD slices (∼30%) suggesting that p75NTR/TrkB imbalance negatively modulates BDNF neuroprotection. Interestingly, reduction of p75NTR levels in the striatum of wild-type mice increased the survival of corticostriatal slices (∼50%) while in HD mice not only increased the cell survival but also prevented the cell death induced by BDNF (Figure 4b). Because JNK activation mediates the proapoptotic actions of neurotrophins20, 21 we next determined whether the cell death induced by BDNF was associated with increased JNK phosphorylation. A significant increase (∼20%) in p-JNK levels was found in extracts obtained from mutant corticostriatal slices treated with BDNF suggesting a correlation between levels of p-JNK and cell death (Figure 4c). Consistent with this idea reduction of p75NTR in wild-type and HD mice significantly decreased JNK phosphorylation (∼25% and ∼15%, respectively, Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

BDNF induces proapoptotic signaling cascades in corticostriatal slices from mutant HdhQ111/Q111 mice. Seven-month-old wild-type (HdhQ7/7) and mutant (HdhQ111/111) mice were injected with GFP-AAV scramble shRNA (scramble shRNA) or GFP-AAV-p75shRNA (p75shRNA) and corticostriatal slices obtained 1 month later. Slices were incubated with BDNF (200 ng/ml) and cell survival determined by a CKK8 assay 24 h later. (a) (Left) Representative immunoblots showing the levels of p75NTR and α-tubulin as a loading control in extracts obtained from corticostriatal slices obtained from wild-type HdhQ7/7 and mutant HdhQ111/111 mice injected with AAV expressing scramble shRNA or p75 shRNA. The histogram represents the relative levels of p75NTR expressed as percentage of wild-type values. Values are given as mean±S.E.M. of four slices/condition/experiment (n=3). Data was analyzed by Student's t-test *P<0.05 respect to wild-type mice. (Right) Confocal microscopy of corticostriatal slices transduced with AAV expressing p75shRNA or scramble shRNA and labeled for p75NTR expression (red). Transduction of p75shRNA results in lack of p75NTR expression as indicated by the absence of red p75NTR labeling in GFP-positive cells. (b) Histograms showing the quantification of cell survival expressed as the percentage of scramble shRNA transduced cells (control). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. of four slices/condition/experiment (n=3). Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey's Multiple comparison test or Student's t-test *P<0.05; **P<0.01 respect to wild-type mice, +P<0.05 respect to scramble shRNA+BDNF treatment. (c) Representative immunoblots showing the levels of JNK, p-JNK and α-tubulin as a loading control in extracts obtained from corticostriatal slices obtained from wild-type HdhQ7/7 and mutant HdhQ111/111 mice and incubated with BDNF for 24 h. The histograms represent the relative p-JNK/JNK ratios considering 100% the ratio obtained in scramble shRNA conditions (control). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. of three independent experiments. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test *P<0.05 respect to wild-type mice, +P<0.05 respect to scramble shRNA+BDNF treatment

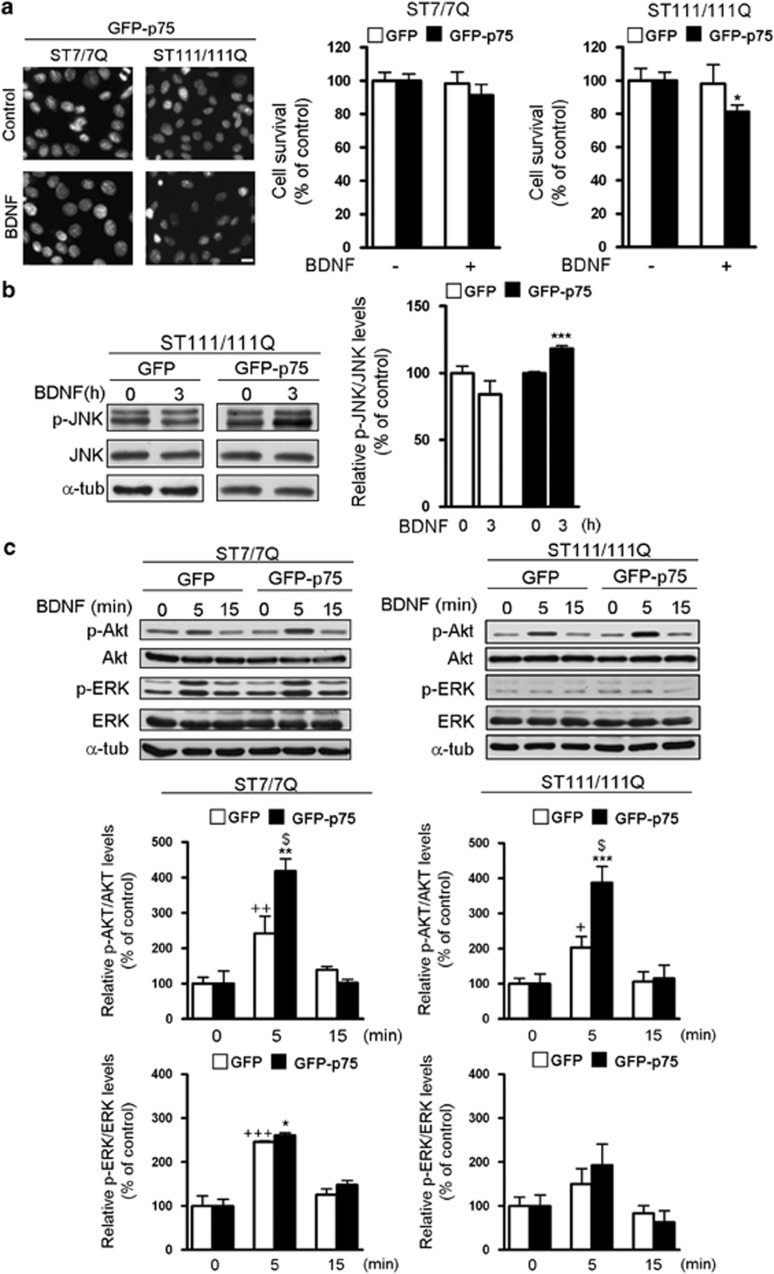

Reduced cell survival of GFP-p75-transfected STHdh111/111Q mutant cells after BDNF treatment is associated with activation of JNK pathway

To further analyze the role of p75NTR/TrkB imbalance in BDNF striatal neuroprotection immortalized striatal cell lines that express wild-type (STHdh7/7Q) or mutant full-length huntingtin (STHdh111/111Q) were used. These mutant cells exhibit reduced levels of TrkB3 but lack p75NTR expression (Supplementary Figure S2b). Therefore, to mimic the p75NTR/TrkB imbalance observed in HD mutant mice, STHdh7/7Q and STHdh111/111Q cells were transfected with GFP or GFP-p75NTR (Supplementary Figure S2b) and then incubated with BDNF. BDNF treatment induced a reduction of cell survival (∼20%) in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells but not in GFP-p75 STHdh7/7Q cells (Figure 5a) consistent with our data in HD corticostriatal slices. Next, we analyzed whether the reduction on cell survival was also related with increased JNK phosphorylation. A significant increase in p-JNK levels (∼20%) without changes in total JNK were found in STHdh111/111Q cells expressing GFP-p75 but not GFP (Figure 5b). Then we analyzed whether BDNF-mediated activation of Akt and ERK1/2 pathways was preserved in STHdh7/7Q and STHdh111/111Q cells transfected with GFP-p75. It is important to mention that STHdh111/111Q cells exhibit increased p-Akt and decreased p-ERK levels at basal conditions,3, 22 levels that were not altered by overexpression of p75NTR (Supplementary Figure S2c). Western blot analysis revealed that BDNF treatment induced a significant increase in Akt phosphorylation in both STHdh7/7Q and STHdh111/111Q cells transfected with GFP (∼100%) and GFP-p75 (∼200%) (Figure 5c). Interestingly, the increase on Akt phosphorylation was significantly higher in GFP-p75-transfected cells than in GFP cells suggesting that overexpression of p75NTR facilitates TrkB-mediated Akt activation. When ERK1/2 phosphorylation was analyzed we found that BDNF treatment induced a robust and similar activation (∼140%) of p-ERK1/2 in GFP and GFP-p75 STHdh7/7Q cells (Figure 5c). In contrast, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was not increased in BDNF-treated GFP or GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells, which agrees with our own published data showing impaired TrkB-mediated ERK1/2 activation in mutant cells.3 These findings indicate that altered p75NTR/TrkB expression modifies BDNF-mediated neuroprotection by increasing the activation of the proapoptotic pathway JNK.

Figure 5.

BDNF-mediated reduction of the survival of GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q mutant cells is associated with activation of apoptotic pathways. Wild-type (ST7/7Q) and mutant (ST111/111Q) huntingtin striatal cells transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were treated with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min) and cell survival was evaluated 24 h later by scoring the percentage of Hoechst-stained nuclei. (a) Photomicrographs of ST7/7Q and ST111/111Q cells stained with Hoechst showing a significant reduction of cell survival in BDNF-treated GFP-p75 ST111/111Q cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of surviving cells is shown as the percentage of total cells in control conditions. The results are representative of seven independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Student's t-test *P<0.05 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 mutant cells. (b) Representative immunoblot showing the levels of JNK, p-JNK and α-tubulin as a loading control in striatal extracts obtained from mutant ST111/111Q cells incubated with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 3 h). The histogram represents the relative p-JNK/JNK ratio considering 100% the ratio obtained in control conditions (vehicle). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test. ***P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 cells. (c) Representative immunoblots showing the levels of Ser-473-Akt (p-Akt), Akt, phosphoERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), ERK1/2 and α-tubulin as a loading control in striatal extracts obtained from wild-type (ST7/7Q) and mutant (ST111/111Q) cells transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 and treated with BDNF (50 ng/ml) for the indicated time points. Blots are representative of four independent experiments. The histograms represent the relative p-Akt/Akt and p-ERK/ERK ratios considering 100% the ratio obtained in control condition (vehicle). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test. +P<0.05, ++P<0.01 versus vehicle-treated GFP cells, *P<0.05, **P<0.01,***P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 cells, $P<0.05 versus BDNF-treated GFP cells

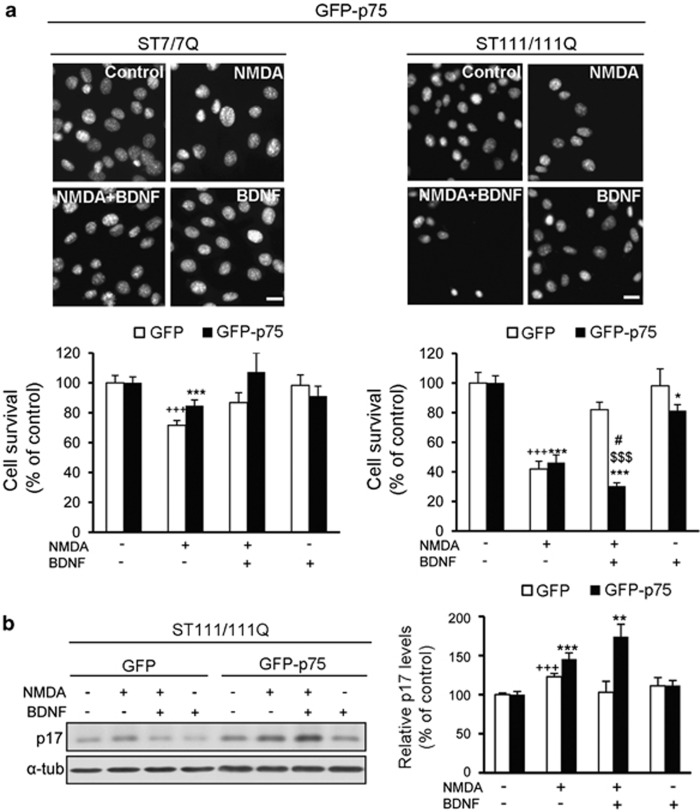

BDNF fails to protect GFP-p75-transfected STHdh111/111Q mutant cells against NMDA-induced excitotoxicity

BDNF-mediated TrkB signaling is required to protect striatal neurons against NMDA-induced excitotoxicity,23 which is well known to contributes to the striatal cell loss in HD.16 Therefore, we investigated whether the p75NTR/TrkB imbalance could affect BDNF neuroprotection against NMDA. GFP or GFP-p75 transfected STHdh7/7Q and STHdh111/111Q cells were treated with BDNF before NMDA exposure and cell survival was analyzed 24 h later (Figure 6). NMDA treatment induced a significant reduction of cell survival in both STHdh7/7Q (∼30%) and STHdh111/111Q cells (∼50%) (Figure 6a). Addition of BDNF before NMDA completely prevented NMDA-induced cell death in STHdh7/7Q cells independently of p75NTR expression (Figure 6a). Surprisingly, in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells BDNF treatment not only failed to protect striatal cells against NMDA-induced cell death but also potentiated it (∼20%). As activation of caspase-3 following NMDA treatment was described in this mutant huntingtin cell line24 we evaluated whether caspase-3 activation was involved in the lack of BDNF neuroprotection against NMDA (Figure 6b). Similar caspase-3 activation was found in GFP or GFP-p75 mutant cells following NMDA incubation (∼40%). However, we found that BDNF completely blocked NMDA-induced activation of caspase-3 in GFP mutant cells while a significant increase (∼75%) was still observed in GFP-p75 mutant cells consistent with the lack of BDNF neuroprotection against NMDA.

Figure 6.

BDNF fails to protect GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q mutant cells against NMDA excitotoxicity. Wild-type (ST7/7Q) and mutant (ST111/111Q) huntingtin striatal cells transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were treated with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min), NMDA (500 μℳ, 30 min) or BDNF before addition of NMDA (NMDA+BDNF) and cell survival was evaluated 24 h later by scoring the percentage of Hoechst-stained nuclei. (a) Representative photomicrographs of wild-type and mutant huntingtin striatal cells stained with Hoechst showing the number of surviving cells in the different conditions (Control, NMDA, NMDA+BDNF and BDNF) Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of surviving cells is shown as the percentage of total cells in control conditions (vehicle). The results are representative of seven independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Student's t-test. +++P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP cells, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 cells, #P<0.05 NMDA-treated GFP-p75 cells versus NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP-p75 cells, $$$P<0.001 NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP mutant cells versus NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP-p75 mutant cells. (b) Mutant huntingtin cells (ST111/111Q) transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were treated with BDNF, NMDA or BDNF before NMDA and cell extracts obtained 3 h later. Immunoblots were performed to detect cleaved caspase-3 (p-17 fragment) and α-tubulin as loading control. The blot is representative of four independent experiments. The histogram represents the relative p-17 levels considering 100% the value obtained in control conditions (vehicle). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Student's t-test. +++P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP mutant cells and **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 mutant cells

Lack of BDNF neuroprotection against NMDA correlates with decreased Akt phosphorylation in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q mutant cells

As BDNF did not protect GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells against NMDA we analyzed activation of Akt and ERK1/2 following BDNF and NMDA treatment. GFP and GFP-p75 transfected STHdh7/7Q and STHdh111/111Q cells were incubated with NMDA alone or with BDNF before NMDA and Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation analyzed by western blot (Figure 7a). NMDA treatment induced a significant increase in p-Akt levels inbothSTHdh7/7Q(GFP:∼80%andGFP-p75:∼150%)andSTHdh111/111Q cells (∼100%) independently of p75NTR transfection. We then analyzed whether BDNF treatment could modify this NMDA-induced Akt phosphorylation. We found that BDNF prevented NMDA-mediated Akt phosphorylation in STHdh7/7Q cells (GFP or GFP-p75) suggesting that BDNF desensitize wild-type cells to further Akt activation by NMDA. Similar results were found when GFP- STHdh111/111Q cells were analyzed. However, in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells BDNF preincubation not only prevented NMDA-induced phosphorylation of Akt but also decreased to levels below those in control mutant cells (∼50%, Figure 7a). NMDA treatment induced a significant increase in p-ERK1/2 levels in both STHdh7/7Q (∼50%) and STHdh111/111Q cells (∼250%). Similar to that observed for Akt, BDNF pretreatment prevented subsequent NMDA-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation independently of p75NTR transfection. These results indicate that p75NTR/TrkB imbalance disturbs BDNF-mediated neuroprotection against NMDA by reducing Akt phosphorylation.

Figure 7.

BDNF prevents NMDA-induced phosphorylation of Akt in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q mutant cells. Wild-type (ST7/7Q) and mutant (ST111/111Q) huntingtin striatal cells transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were treated with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min), NMDA (500 μℳ, 30 min) or BDNF before addition of NMDA (NMDA+BDNF) for the indicated time periods. Cells were lysed and immunoblots performed to detect Ser-473-Akt (p-Akt) and Akt (a) or phosphoERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) and ERK1/2 (b). α-tubulin was used as a loading control. The blots are representative of four independent experiments. The histograms represent the relative p-Akt/Akt and p-ERK/ERK ratios considering 100% the ratio obtained in control conditions (vehicle). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test. +P<0.05, ++P<0.01, +++P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP cells, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 cells, $P<0.05, $$$P<0.001 NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP mutant cells versus NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP-p75 mutant cells

Reduced Akt phosphorylation in GFP-p75-transfected STHdh111/111Q mutant cells correlates with increased PP1 levels

Akt phosphorylation at Ser-473 can be regulated by the activity of PP1 and PHLPP1 phosphates.25, 26, 27 As we observed decreased Akt Ser-473-phosphorylation in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells after BDNF and NMDA treatment, PP1 and PHLPP1 levels were evaluated. A significant increase in PP1 levels was found in GFP (∼20%) and GFP-p75 (∼30%) STHdh111/111Q cells following NMDA treatment (Figure 8a). Importantly, in GFP-p75 but not in GFP mutant cells incubation with BDNF before NMDA significantly increased PP1 levels (∼80% compared with untreated cells and∼50% compared with NMDA-treated cells). No differences on PHLPP1 levels were found between GFP and GFP-p75 mutant cells at any analyzed condition (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 8.

Lack of BDNF neuroprotection against NMDA excitotoxicity is mediated by PP1-induced dephosphorylation of Akt in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q mutant cells. Mutant huntingtin (ST111/111Q) striatal cells transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were incubated with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min), NMDA (500 μℳ, 30 min) or BDNF before NMDA treatment and cell extracts obtained 15 min later. (a) Representative immunoblot showing the levels of PP1 and α- tubulin as loading control. The blot is representative of five independent experiments. The histogram represents the relative PP1 levels considering 100% the value obtained in control conditions (vehicle). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test. +P<0.05 versus vehicle-treated GFP cells, **P<0.01 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 cells, ##P<0.01 NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP-p75 cells versus NMDA-treated GFP-p75 cells, $$P<0.01 NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP cells versus NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP-p75 cells. (b) Mutant huntingtin striatal cells (ST111/111Q) transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were treated with the PP1 inhibitor OA (200 nℳ, 30 min) before incubation with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min), NMDA (500 μℳ, 30 min) or BDNF and NMDA (NMDA+BDNF). Cell extracts were obtained 15 min later and immunoblots performed to detect Ser-473-Akt (p-Akt), Akt and α-tubulin as a loading control. The blots are representative of four independent experiments. The histograms represent the relative p-Akt/Akt ratio considering 100% the ratio obtained in control conditions (vehicle). Values are given as mean±S.E.M. Data was analyzed by Student's t-test. +P<0.05, +++P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP cells, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 versus vehicle-treated GFP-p75 cells, $P<0.05 NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP cells versus NMDA+BDNF-treated GFP-p75 cells. (c) Mutant huntingtin striatal cells (ST111/111Q) transfected with GFP or GFP-p75 were treated with or without OA (200 nℳ, 30 min) before incubation with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min) and then exposed to NMDA (500 μℳ, 30 min). Cell survival was evaluated 24 h later by scoring the percentage of Hoechst-stained nuclei. Representative photomicrographs of wild-type (ST7/7Q) and mutant (ST111/111Q) huntingtin cells stained with Hoechst showing the number of surviving cells in the different conditions (Control, NMDA, NMDA+BDNF and BDNF). Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of surviving cells is shown as the percentage of total cells in control conditions (vehicle). The results are representative of seven independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as the mean±S.E.M.

Inhibition of PP1 restores Akt phosphorylation and BDNF neuroprotection in GFP-p75-transfected STHdh111/111Q mutant cells

To confirm a functional role for PP1 in the lack of BDNF neuroprotection GFP and GFP-p75-transfected STHdh111/111Q cells were treated with OA to inhibit PP1 activity and p-Akt levels analyzed by western blot (Figure 8b). Inhibition of PP1 in GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells blocked the reduction of Akt phosphorylation induced by BDNF treatment. Moreover and consistent with a detrimental role of PP1 on BDNF neuroprotection the cell death of GFP-p75 STHdh111/111Q cells induced by BDNF and/or NMDA was completely prevented by pretreatment with OA (Figure 8c). Altogether, these results support the involvement of PP1 in the increased p75-mediated vulnerability of mutant huntingtin striatal cells to NMDA excitotoxicity.

Discussion

Several evidences implicate reduced levels of BDNF in HD pathology, which has emphasized the study of therapeutic strategies based on BDNF administration for HD treatment.1, 28, 29 BDNF-mediated neuronal survival is primarily associated with activation of TrkB receptors.30, 31 However, BDNF can also binds to p75NTR, which could either potentiate Trk function9, 32, 33, 34 or signal independently to activate cell death cascades.20, 35, 36 In this study, we found an imbalance between p75NTR and TrkB expression in two distinct HD mouse models: HdhQ111/111 mutant knockin mice and R6/1 transgenic mice that was also manifested in the putamen of HD patients supporting the idea that p75NTR/TrkB imbalance is relevant to HD pathology. p75NTR upregulation was associated with increased p75NTR mRNA expression, which agrees with previous studies showing increased p75NTR and reduced TrkB mRNA levels in the caudate of HD patients.4 Deregulation of gene transcription has been implicated in HD pathology. In particular upregulation of the transcription factor Sp1 has been described in cellular and transgenic models of HD suggesting that increased Sp1-mediated transcription could contribute to HD pathology.37 Interestingly, p75NTR expression is dependent on binding of Sp1 to the p75NTR proximal promoter,38, 39 which allows us to speculate that aberrant Sp1 activity could underlie the upregulation of p75NTR mRNA in HD. Our data also demonstrate that upregulation of p75NTR protein levels in HD brain follows a rostro-caudal gradient with higher p75NTR expression at the rostral striatum. Notably, brain tomography studies demonstrate severe atrophy of the head caudate early in the disease process along the rostro-caudal axis40 suggesting a correlation between increased p75NTR levels and striatal atrophy and dysfunction. Consistent with this hypothesis we found a good colocalization between p75NTR and DARPP32, a well known marker for striatal medium spiny neurons, the most vulnerable neurons in HD. In fact, this is the first time showing p75NTR expression in DARPP32 neurons as most of the previous studies reported p75NTR immunoreactivity in large cholinergic interneurons.11 In this new scenario, it is important to determine whether the imbalance between p75NTR and TrkB expression could affect BDNF neuroprotection. Our studies demonstrate reduced cell survival of STHdh111/111Q mutant cells and corticostriatal slices from HdhQ111/111 mutant mice after BDNF treatment supporting the idea that altered expression of BDNF receptors could contribute to disturbing BDNF neuronal protection. This result agrees with previous studies showing BDNF-mediated cell death of hippocampal neurons expressing high levels of p75NTR but lacking TrkB or TrkC receptors.20, 36 Moreover, we demonstrate that BDNF-induced cell death was associated with a significant activation of the JNK pathway that was reported to have an important role in p75NTR-mediated cell death.41, 42 These findings together with our published data showing lack of BDNF-mediated activation of ERK1/2 in mutant huntingtin cells (Figure 6 and Gines et al.3) suggest that mutant huntingtin induces neuronal cell death not only by altering p75NTR and TrkB expression but also their downstream signaling. In view of this data, we propose that aberrant BDNF signaling could participate in the increased susceptibility of mutant huntingtin striatal cells to NMDA excitotoxicity. In support of this hypothesis we found that BDNF incubation before NMDA treatment not only fails to reduce GFP-p75 mutant huntingtin cell death but potentiates it. In association with increased cell death we found higher caspase-3 activation, which is known to be crucial for cell death triggered by over-activation of p75NTR.36, 43 Similarly, reduced p75NTR/TrkB ratio as a consequence of seizure induction in rats also promotes neuronal cell death that was associated with increased binding of BDNF to p75NTR.44 Besides increased JNK activation lack of BDNF neuroprotection against NMDA was also related with reduced Akt activation. Dephosphorylation of Akt depends on several Ser/Thr phosphatases. PP2-A dephosphorylates Akt at Thr-308,45 whereas PP1 and PHLPP1 at Ser-473.25, 27 No changes on PHLPP1 levels were found in BDNF/NMDA-treated GFP-p75 mutant huntingtin cells revealing that this phosphatase unlikely contributes to Akt inactivation. By contrast, PP1 levels were significantly increased following BDNF and NMDA treatment suggesting a mechanistic link between PP1 and Akt inactivation. Supporting this view, BDNF/NMDA-induced dephosphorylation of Akt was blocked by inhibition of PP1 by OA treatment. Moreover, we also demonstrate that PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of Akt contributes to mutant huntingtin cell death as inhibition of PP1 prevented BDNF/NMDA-induced cell death of GFP-p75 mutant cells. Interestingly deregulation of PP1 activity in HD mice has been associated with NMDA-mediated striatal cell death46 and NMDA-induced cell death of retinal ganglion cells has been related with PP1-mediated Akt dephosphorylation.26 Altogether, this data suggest that a dysfunctional signaling cross-talk between TrkB, p75NTR and NMDAR could contribute to increase striatal cell vulnerability in HD (Supplementary Figure 3). These results may have important consequences for the potential use of BDNF as a therapeutic agent in HD. Thus, exogenous BDNF administration or pharmacological treatments that raise BDNF levels only ameliorate or partially improve morphological phenotypes or motor and cognitive behavior in different HD mouse models,47, 48, 49, 50, 51 which could be related with the dysfunctional signaling of TrkB and p75NTR demonstrated in the present study. In view of these results, a better understanding of the physiological interactions between p75NTR and TrkB in HD would improve the design of new neuroprotective therapies for HD treatment

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and antibodies

BDNF was obtained from Peprotech EC Ltd (London UK), Okadaic Acid was obtained from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN, USA), NMDA (N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Phospho p44/42 ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), Phospho-Akt (Ser-473), Phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), total ERK1/2, total Akt and total SAPK/JNK were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). TrkB polyclonal antibody that recognizes the full-length TrkB isoform (sc-7268; C-tal epitope) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). TrkB monoclonal antibody that recognizes full-length and truncated TrkB isoforms and anti-DARPP32 was purchased from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-p75NTR was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA), anti-PP1 (Protein phosphatase 1); anti-parvalbumine and anti-α-tubulin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). β-actin (clone C4) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA, USA), anti-NeuN was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, Bedford, MA, USA) and anti-GFAP was from Dako A/S (Glostrup, Denmark). IgG HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from Promega and Cy3 anti-rabbit, Cy2 anti-mouse secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG conjugate was from Invitrogen.

Cell cultures

Conditionally immortalized wild-type STHdh7/7Q and mutant STHdh111/111Q striatal neuronal progenitor cell lines expressing endogenous levels of normal and mutant full-length huntingtin with 7 and 111 glutamines, respectively, were generated from wild-type HdhQ7/7 and homozygous HdhQ111/111 littermate embryos.22 The knockin models represent faithfully the HD mutation carried by patients as elongated polyglutamine tracts are placed within the correct context of the murine Hdh gene. Thus, immortalized striatal cells accurately express normal and mutant huntingtin and do not exhibit amino terminal inclusions, which allow us to study changes involved in early HD pathogenesis. Striatal cells were grown at 33 °C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% streptomycin-penicillin, 2 mℳ L-glutamine, 1 mℳ sodium pyruvate and 400 μg/ml G418 (Geneticin; Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Mouse septal neuron × neuroblastoma hybrid SN56 cells (cell line with negligible TrkB expression) and T48 cells (SN56 cells transfected clone expressing TrkB) were created and kindly provided by Dr. KYe (Department of Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta). SN56 cells were maintained at 37 °C in DMEM medium containing 1 mℳ pyruvate and 10% FBS and T48 cells stably transfected with rat TrkB were cultured in the same medium but containing 300 μg/ml G418.

Genetic Huntington's disease mouse models

HdhQ111 knockin mice expressing mutant huntingtin with 111 glutamine residues were maintained on a C57BL/6 genetic background.52 HdhQ7/111 heterozygous males and females were intercrossed to generate age-matched HdhQ111/111 homozygous and HdhQ7/7 wild-type littermates. R6/1 transgenic mice (B6CBA background) expressing exon-1 mutant huntingtin with 145 glutamines under the HD human promoter and their wild-type littermates were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).53 The animals were housed with access to food and water ad libitum in a colony room kept at 19–22 °C and 40–60% humidity, under a 12 : 12 h light/dark cycle. All procedures were performed in compliance with the European Community guidelines for the care and use of the laboratory animals (86/609/EEC), and approved by the local animal care committee of Universitat de Barcelona (404/12) and Generalitat de Catalunya (DAAM5712).

Postmortem brain tissues

Samples of the putamen nucleus from one patient with HD grade 1 (73 years, postmortem intervals of 7 h), nine patients with HD grade 3 and 4 (71, 63, 65, 60, 47, 44, 40, 39, 28 years, postmortem intervals of 4–15 h) and 10 control cases (77, 74, 71, 68, 65, 64, 60, 59, 56, 39 years, postmortem intervals of 4–23 h ) were supplied by the Banc de Teixits Neurològics (Servei Científico-Tècnics, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain). The Banc de Teixits Neurològics was established to provide human postmortem brains to researchers in Spain taking into due consideration all the ethical guidelines of the latest Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects under study.

Cell transfection

All DNA constructs were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 as instructed by the manufacturer. Both wild-type STHdh7/7Q and mutant STHdh111/111Q huntingtin striatal cells were transfected at 50% of confluence with human p75 neurotrophin receptor tagged with GFP at the C-terminus (generously provided by Dr. Formaggio, Department of Medicine and Public Health, Section Pharmacology, University of Verona, Italy). As a control condition cells were transfected with GFP vector from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Transfection efficiencies were estimated by flow cytometry and are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from striatum of HD mutant and wild-type mice using the Total RNA Isolation Nucleospin RNA II Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Purified RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed using the StrataScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis System (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The cDNA synthesis was performed at 42 °C for 60 min in a final volume of 20 μl according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was then analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using the following TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA): 18S (Hs99999901_s1) and p75 (Mm00446294_m1). RT-PCR was performed in 25 μl of final volume on 96-well plates, in a reaction buffer containing 12.5 μl TaqMan Gene Expression Assays and 20 ng of cDNA. Reactions included 40 cycles of a two-step PCR: 95 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 1 min, after initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min. All quantitative-PCR assays were performed in duplicate and repeated in at least three independent experiments. To provide negative controls and exclude contamination by genomic DNA, the RT was omitted in the cDNA synthesis step, and the samples were subjected to the PCR reaction in the same manner with each TaqMan Gene Expression Assay. The quantitative-PCR data was quantified using the comparative quantitation analysis program of MxPro Q-PCRanalysis software version 3.0 (Stratagene). The CT) value for each reaction, and the relative level of gene expression for each sample were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.54 To correct for loading differences, the values were normalized according to the level of expression of the housekeeping gene, 18S, within each sample. Its CT value was subtracted from that of the specific genes to obtain a ΔCT value. Differences (ΔΔCT) between the ΔCT values obtained for the control mice (calibrators) and the ΔCT values for the R6/1 or the HdhQ111/111 mice were determined. The relative quantitative value was then expressed as 2−ΔΔCT, representing the fold change in gene expression normalized to the endogenous control and relative to the calibrators.

Drug treatments of striatal cell lines

All drug treatments were performed 48 h after transfection. To induce NMDA excitotoxicity transfected wild-type STHdh7/7Q and mutant STHdh111/111Q huntingtin striatal cells were exposed to 500 μℳ NMDA for 30 min in Locke's solution (154 mm NaCl, 5.6 mm KCl, 2.3 mm CaCl2, 3.6 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm HEPES, 5.6 mm glucose and 10 μm glycine). After NMDA treatment, medium was replaced by fresh DMEM medium containing 2.5% FBS and cell survival was analyzed 24 h later. To analyze the neuroprotective role of BDNF against NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity transfected wild-type and mutant huntingtin striatal cells were treated for 30 min in serum-free DMEM medium containing 50 ng/ml BDNF before NMDA exposure (500 μℳ, 30 min). After NMDA treatment medium was replaced by fresh DMEM medium containing 2.5% FBS and cell survival was analyzed 24 h post-treatment. To analyze basal BDNF signaling, transfected wild-type and mutant huntingtin striatal cells were placed in DMEM serum-free medium for 3 h and then exposed to BDNF (50 ng/ml) for different time periods, (0, 5 and 15 min). To study BDNF signaling in NMDA-treated conditions transfected wild-type and mutant huntingtin striatal cells were treated with BDNF (50 ng/ml) for 30 min before NMDA incubation (500 μℳ) and total cell extracts were collected at different time periods (0, 5 and 15 min). To analyze apoptotic cascades (cleaved caspase-3 and phospho-JNK levels), cells were treated with BDNF (50 ng/ml, 30 min) or with BDNF before NMDA exposure (500 μℳ, 30 min) and cell extracts collected 3 h later. Finally, to test the role of protein phosphotase 1 (PP1) in HD pathology, mutant striatal cells were exposed to 200 nℳ of the PP1 inhibitor ,OA (30 min) before BDNF treatment (50 ng/ml, 30 min). After BDNF incubation cells were treated with NMDA (500 μℳ, 30 min), medium replaced by fresh DMEM medium and PP1 levels analyzed by western blot in total extracts obtained 15 min post-treatment. In parallel experiment cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and cell survival analyzed 24 h later.

Cell survival

Cell survival of striatal cells was assessed by nuclear DNA staining with Hoechst 33258. Cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, washed twice in PBS, and stained with Hoechst 33258 (1 μg/ml) for 5 min. Stained cells were then washed twice with PBS and mounted under glass coverslips with Mowiol. Cell survival is represented as the proportion of Hoechst-stained nuclei counted in treated cells compared with the number of control cells (vehicle-treated). Forty fields were counted per condition and experiment, comprising at least 30–40 cells. Data are given as mean±S.E.M. of values obtained in seven independent experiments performed in triplicate.

AAV-mediated shp75 expression vectors

For knockdown p75NTR expression we designed a siRNA oligomer targeting the mouse p75NTR: Ngfr-1 (5′ GACGCATCCAGAGAGCTGA 3′). This siRNA was then used to obtain the corresponding shRNA to clone into a rAAV2/8-GFP adenoviral vector (BamHI site at 5′ and AgeI at the 3′). The rAAV2/8 plasmids and infectious AAV viral particles containing GFP expression cassette with scrambled shRNA (AAV-shRNAGFP) or p75shRNA (AAV-shp75GFP) were generated by the Unitat de Producció de Vectors from the Center of Animal Biotechnology and Gene Therapy at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Intrastriatal injection of adenoviral vectors

Seven-months-old wild-type HdhQ7/7 and mutant HdhQ111/111 mice (n=4–5) were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (40–60 mg/Kg) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus for bilateral intrastriatal injections of rAAV2/8 expressing shp75 or control shRNA (3 μl; 1,53 × 109 GC ). A small incision was made in the scalp, and the striatum was marked using the following stereotaxic coordinates to Bergman: anteroposterior (AP), +0.6 mm; mediolateral (ML), +2 mm; and 2.7 mm below the dural surface with the incisor bar at 3 mm above the interaural line. Viral vector was injected using a 10 μl-Hamilton microliter syringe at an infusion rate of 0, 5 μl/min; the needle was left in place for 5 min to ensure complete diffusion of the viruses and then slowly retracted from the brain. Four weeks after injections, the mice were killed to obtain corticostriatal organotypic cultures as mentioned below.

Corticostriatal organotypic cultures

Corticostriatal slice cultures were prepared by the interface culture method55 slightly modified. In brief, 8-months-old wild-type HdhQ7/7 and mutant HdhQ111/111 mice were killed by instant decapitation and their brains were quickly removed and placed in a petri dish containing dissecting salt medium (MEMp: (50% (vol/vol) MEM, 25 mℳ HEPES and 2 mℳ glutamine without antibiotics) under sterile conditions. After removal of the meninges the brains were sectioned coronally (400 μm) by using a McIlwain tissue chopper (Mickle Laboratory, Cambridge, UK). The resulting brain slices were placed in incubation culture medium (MEMi: 50% (vol/vol) MEM, 25 mℳ HEPES, 25% (vol/vol) HBSS, 25% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated horse serum, 2 mℳ glutamine, 1 ml of penicillin/streptomycin solution and 0.044% (vol/vol) NaHCO3). These slices were then trimmed to include the dorsal one half of the striatum with the overlying frontoparietal neocortex. From each donor mice an average of seven corticostriatal cultures were obtained using both hemispheres. The slices were stored for 1 h at 4 °C before being transferred to 24-well plates contained inserts of humidified porous membranes (0,4 μm Millicell, 12 mm diameter Millipore) in 250 μl of culture medium. The cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere at a relative humidity of 95%. Culture viability was first determined by subjective judgment of the transparency, color and border morphology. To validate the method, the viability of our corticostriatal organotypic slice cultures was analyzed using a standardized protocol for PI uptake. Briefly, 2 h after transferring the slices to the transwell, 20 μl of 0,1 mℳ PI was added to the organotypic culture. This concentration is kept in the medium during the 24 h period incubation. After 24 h, slices were then incubated (30 min at 37 °C) with 0.01% Calcein AM, a cell-permeant dye used to determine cell viability (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA ) and images were analyzed by confocal microscopy.

CCK-8 cytotoxicity assay

Cell viability of corticostriatal slices was assessed by WST-8 assay using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), in which colored formazan was formed in viable cells in response to cellular dehydrogenase activity. Briefly, after BDNF treatment (200 ng/ml), 25 μl of Cell Counting Assay Kit-8 solution was added to each corticostriatal slice. After 3 h or 24 h of incubation, 100 μl of medium from each slice culture was dispensed in a 96-well plate and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The cell viability was calculated as the ratio between the absorbance measurements at 3 h and 24 h and the results expressed as the percentage of viable cells relative to GFP-vehicle-treated slices (control). Each experiment contained four readings for each experimental condition.

Immunofluorescence

For immunohistochemical analysis, homozygous mutant HdhQ111/111 and wild-type HdhQ7/7 mice at 8 months of age or wild-type and R6/1 mice at 30 weeks of age (n=3 for each condition) were deeply anesthetized and immediately perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate buffer. Brains were removed and postfixed overnight in the same solution, cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose and then frozen in dry ice-cooled methylbutane. Serial coronal cryostat sections (30 μm) through the whole brain were collected in PBS as free-floating sections. Sections were rinsed three times in PBS, incubated with NH4Cl 50 mℳ, and permeabilized with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100. Blocking was performed with PBS containing 0, 2% BSA and 5% normal goat serum (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were then washed in PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-p75 (1 : 100), anti-GFAP (1 : 100), anti-DARPP32 (1 : 1000) or anti-parvalbumin (1 : 1250) antibodies and detected with Cy3 anti-rabbit and Cy2 anti-mouse (1 : 200) secondary antibodies. Following secondary antibody incubation, slices were rinsed in PBS. As negative controls, some sections were processed as described in the absence of primary antibody and no signal was detected. Immunofluorescence was analyzed by confocal microscopy using a TCS SL laser scanning confocal spectral microscope (Leica Microsystems Heidelberg GmbH, Manheim, Germany). For human brain immunofluorescence analysis, paraffin sections of the putamen nucleus from one patient with HD grade 1 (73 years, 7 h postmortem) was supplied by the Banc de Teixits Neurològics (Servei Científico-Tècnics, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain). Paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated using a xylene/ethanol series followed by rinsing with PBS. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed in citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (DAKO) for 20 min. Sections were rinsed three times in PBS, incubated with NH4Cl 50 mℳ, and permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 45 min. Blocking was performed with PBS containing 1% BSA and 10% normal horse serum (Pierce) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-p75 (1 : 100), and anti-DARPP32 (1 : 1000) diluted in blocking buffer and detected with Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Conjugate (green) and Cy2 anti-mouse (1 : 200) secondary antibodies. Following secondary antibody incubation, slices were rinsed in PBS. As negative controls, some sections were processed as described in the absence of primary antibody and no signal was detected. Immunofluorescence was analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning spectral confocal microscope (Leica) with Argon and HeNe lasers attached to a Leica DMI6000 inverted microscope.

Image analysis of striatal coronal sections

Coronal sections spaced 240 μm apart comprising rostral, middle and caudal levels of the striatum (1,54 mm to −0.7 mm from Bergman) from wild-type and R6/1 mice (n=3) were examined with Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning spectral confocal microscope (Leica) with Argon and HeNe lasers attached to a Leica DMI6000 inverted microscope. Confocal images were taken using a × 40 numerical aperture objective with a × 1 digital zoom and standard (one Airy disk) pinhole. For each coronal section, the entire three-dimensional stack of images from the ventral surface to the top of the section was obtained by using the Z drive in the Leica TCS SP5 microscope. The size of the optical image was 0.5 μm. For each sample, 54 sections (6 × 9) were captured and subsequently stitched using the tile scan feature of the Leica LAS AF 2.1.1 software to allow complete visualization of the striatum. Quantitative analyses were performed using the freeware ImageJ v1.33 by Wayne Rasband (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Briefly, for each stitched image maximum projections was generated and mean pixel intensity was measured from the selected delineated area.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Wild-type and HD mice were killed by cervical dislocation and brains quickly removed, dissected, frozen in dry ice and stored at −80 °C until use. Protein extracts were prepared from striatal brain samples and striatal cell cultures by sonication on ice for 10 s in lysis buffer containing 50 mℳ Tris base (pH 7.4), 150 mℳ NaCl, 0.1 mℳ phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 1% NP-40 and supplemented with 1 mℳ sodium orthovanadate and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min and the protein contents determined by (Detergent-Compatible) Protein Assay (Bicinchoninic acid, BCA; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein extracts (30 μg) were mixed with 4X SDS sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, resolved by 8–12% sSDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH, USA). Blots were blocked in 10% non-fat powdered milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (50 mℳ Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH7.4, 0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: TrkB polyclonal antibody (1 : 500; cellular extracts), TrkB monoclonal antibody (1 : 1000, striatal extracts), p75 antibody (1 : 1000), anti-NeuN (1 : 1000), anti-GFAP (1 : 1000), anti-GFP rabbit antibody (1 : 500), Phospho p44/42 ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (1 : 1000), Phospho-Akt (Ser-473) (1 : 1000), Phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (1 : 1000), total ERK1/2 (1 : 2500), total Akt (1 : 1000), SAPK/JNK (1 : 1000), α-tubulin (1 : 50 000) or β-actin (1 : 20 000). The membranes were then rinsed three times with Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (TBS-T) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After washing for 30 min with TBS-T, the membranes were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence substrate kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The Gel-Pro densitometry program (Gel-Pro Analyzer for Windows- version 4.0.00.001) was used to quantify the different immunoreactive bands relative to the intensity of the α-tubulin or actin band in the same membranes. Data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. of band density obtained in independent experiments or samples.

Statistical analysis

All of the data were analyzed with the program GraphPad Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Results are expressed as mean±S.E.M. Experimental data were analyzed either by a one- or two-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison test or by Student's t-test. A value of P<0.05 was accepted as denoting statistical significant differences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M Macdonald for providing the huntingtin knock-in striatal cell lines. The authors thank Dr. Formaggio for providing human p75 neurotrophin receptor tagged with GFP at the C-terminus and Dr. K Ye for providing SN56 cells and T48 cells. We are very grateful to Ana Lopez and Maria Teresa Muñoz for technical assistance and Dr. Teresa Rodrigo and the staff of the animal care facility (Facultad de Psicologia, Universitat de Barcelona) for their help. We are grateful to the University of Barcelona and the Institute of Neuropathology Brain Banks (Barcelona, Spain) for providing brain samples from control subjects and HD patients. We thank members of our laboratory for helpful discussion. This work was supported by grants from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2009-07077 and SAF2012-39142 to S.G., SAF2011-29507 to J.A.); Centro de Investigaciones Biomédicas en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED CB06/05/0054 and CB06/05/0042); Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias Instituto de Salud Carlos III (RETICS: RD06/0010/0006) and Cure Huntington's Disease Initiative (A-3758 to S.G.)

Glossary

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DAPI

4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole

- DARPP32

Dopamine- and cAMP-regulated protein with molecular weight of 32 kDa

- ERK

Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase

- GFAP

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HD

Huntington's Disease

- JNK

Jun N-terminal Kinase.

- NeuN

Neuronal nuclear antigen

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PHLPP1

PH domain and Leucine rich repeat Protein Phosphatases

- PP1

protein phosphatase 1

- TrkB

Tyrosine-related kinase B receptor

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Verkhratsky

Supplementary Material

References

- Zuccato C, Cattaneo E. Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Huntington's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:294–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gines S, Bosch M, Marco S, Gavalda N, Diaz-Hernandez M, Lucas JJ, et al. Reduced expression of the TrkB receptor in Huntington's disease mouse models and in human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:649–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gines S, Paoletti P, Alberch J. Impaired TrkB-mediated ERK1/2 activation in huntington disease knock-in striatal cells involves reduced p52/p46 Shc expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21537–21548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C, Marullo M, Conforti P, MacDonald ME, Tartari M, Cattaneo E. Systematic assessment of BDNF and its receptor levels in human cortices affected by Huntington's disease. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:225–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SJ, Reddy EP. Transducers of life and death: TNF receptor superfamily and associated proteins. Oncogene. 1996;12:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Pang PT, Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrn1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A, Willnow TE, Petersen CM. p75NTR—live or let die. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip NY, Stitt TN, Tapley P, Klein R, Glass DJ, Fandl J, et al. Similarities and differences in the way neurotrophins interact with the Trk receptors in neuronal and nonneuronal cells. Neuron. 1993;10:137–149. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90306-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee IJ, Barker PA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor binding to the p75 neurotrophin receptor reduces TrkA signaling while increasing serine phosphorylation in the TrkA intracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23547–23551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PA. p75NTR: A study in contrasts. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:346–356. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pioro EP, Cuello AC. Distribution of nerve growth factor receptor-like immunoreactivity in the adult rat central nervous system. Effect of colchicine and correlation with the cholinergic system—I. Forebrain. Neuroscience. 1990;34:57–87. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90304-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb R. The protean actions of neurotrophins and their receptors on the life and death of neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesmaier E, Schlager G, Wegleiter K, Hermann M, Urbanek M, Simbruner G, et al. Role of p75NTR in NMDAR-mediated excitotoxic brain injury in neonatal mice. Brain Res. 2010;1355:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hota SK, Barhwal K, Singh SB, Ilavazhagan G. Chronic hypobaric hypoxia induced apoptosis in CA1 region of hippocampus: a possible role of NMDAR mediated p75NTR upregulation. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JD, Chartisathian K, Chase TN, Butcher LL. Overexpression of neurotrophin receptor p75 contributes to the excitotoxin-induced cholinergic neuronal death in rat basal forebrain. Brain Res. 2000;853:174–185. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan MM, Raymond LA. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function and excitotoxicity in Huntington's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:272–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C, Ciammola A, Rigamonti D, Leavitt BR, Goffredo D, Conti L, et al. Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington's disease. Science. 2001;293:493–498. doi: 10.1126/science.1059581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, Ferrante RJ, Bird ED, Richardson EP., Jr. Neuropathological classification of Huntington's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44:559–577. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanbury R, Charles V, Chen EY, Leventhal L, Rosenstein JM, Mufson EJ, et al. Excitotoxic and metabolic damage to the rodent striatum: role of the P75 neurotrophin receptor and glial progenitors. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:291–305. doi: 10.1002/cne.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WJ. Neurotrophins induce death of hippocampal neurons via the p75 receptor. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6340–6346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06340.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SO, Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Carter B, Chao MV. Competitive signaling between TrkA and p75 nerve growth factor receptors determines cell survival. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3273–3281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03273.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gines S, Seong IS, Fossale E, Ivanova E, Trettel F, Gusella JF, et al. Specific progressive cAMP reduction implicates energy deficit in presymptomatic Huntington's disease knock-in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:497–508. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Navarro E, Canudas AM, Akerund P, Alberch J, Arenas E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin-3, and neurotrophin-4/5 prevent the death of striatal projection neurons in a rodent model of Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2190–2199. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xifro X, Garcia-Martinez JM, del TD, Alberch J, Perez-Navarro E. Calcineurin is involved in the early activation of NMDA-mediated cell death in mutant huntingtin knock-in striatal cells. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1596–1612. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brognard J, Sierecki E, Gao T, Newton AC. PHLPP and a second isoform, PHLPP2, differentially attenuate the amplitude of Akt signaling by regulating distinct Akt isoforms. Mol Cell. 2007;25:917–931. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa T, Shimura M, Endo S, Takahashi H, Mori N, Tamai M. N-methyl-𝒟-aspartic acid suppresses Akt activity through protein phosphatase in retinal ganglion cells. Mol Vis. 2005;11:1173–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Gong LL, Yuan D, Deng M, Zeng XM, Chen LL, et al. Protein phosphatase-1 regulates Akt1 signal transduction pathway to control gene expression, cell survival and differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1448–1462. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberch J, Perez-Navarro E, Canals JM. Neurotrophic factors in Huntington's disease. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:195–229. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)46014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C, Liber D, Ramos C, Tarditi A, Rigamonti D, Tartari M, et al. Progressive loss of BDNF in a mouse model of Huntington's disease and rescue by BDNF delivery. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numakawa T, Yokomaku D, Richards M, Hori H, Adachi N, Kunugi H. Functional interactions between steroid hormones and neurotrophin BDNF. World J Biol Chem. 2010;1:133–143. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaper SD. The neurotrophin family of neurotrophic factors: an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;846:1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-536-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibel M, Hoppe E, Barde YA. Biochemical and functional interactions between the neurotrophin receptors trk and p75NTR. EMBO J. 1999;18:616–622. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceni C, Kommaddi RP, Thomas R, Vereker E, Liu X, McPherson PS, et al. The p75NTR intracellular domain generated by neurotrophin-induced receptor cleavage potentiates Trk signaling. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2299–2307. doi: 10.1242/jcs.062612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Volosin M, Cragnolini AB, Hempstead BL, Friedman WJ. ProNGF induces PTEN via p75NTR to suppress Trk-mediated survival signaling in brain neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15608–15615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2581-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson EJ, May LM, Osborne SL, Reid K, Underwood CK, Meunier FA, et al. p75 neurotrophin receptor mediates neuronal cell death by activating GIRK channels through phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2008;28:315–324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2699-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy CM, Friedman JE, Friedman WJ. Mechanisms of p75-mediated death of hippocampal neurons. Role of caspases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34295–34302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Norflus F, Singh B, Swindell MK, Buzescu R, Bejarano M, et al. Sp1 is up-regulated in cellular and transgenic models of Huntington disease, and its reduction is neuroprotective. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16672–16680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kommaddi RP, Dickson KM, Barker PA. Stress-induced expression of the p75 neurotrophin receptor is regulated by O-GlcNAcylation of the Sp1 transcription factor. J Neurochem. 2011;116:396–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A, Ho WC, Forte S, Dickson K, Boutilier J, Favell K, et al. Hypo-osmolar stress induces p75NTR expression by activating Sp1-dependent transcription. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1498–1506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4806-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J, Havrdova E, Ruzicka E. Atrophy of caudate nucleus in Huntington's disease measured by computed tomography. J Neurol. 2000;247:880–881. doi: 10.1007/s004150070078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini C, Rossi F, Formaggio E, Bernardoni R, Cecconi D, Della-Bianca V. Characterization of the signaling pathway downstream p75 neurotrophin receptor involved in beta-amyloid peptide-dependent cell death. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;25:141–156. doi: 10.1385/JMN:25:2:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenchappa RS, Tep C, Korade Z, Urra S, Bronfman FC, Yoon SO, et al. p75 neurotrophin receptor-mediated apoptosis in sympathetic neurons involves a biphasic activation of JNK and up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme/ADAM17. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20358–20368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo MF, Aviles-Reyes RX, Villarreal A, Barker P, Reines AG, Ramos AJ. p75 NTR expression is induced in isolated neurons of the penumbra after ischemia by cortical devascularization. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1892–1903. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsain N, Nunez N, Anastasia A, Masco DH. Status epilepticus induces a TrkB to p75 neurotrophin receptor switch and increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor interaction with p75 neurotrophin receptor: an initial event in neuronal injury induction. Neuroscience. 2008;154:978–993. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YC, Huang KY, Yang CH, Yang YS, Lee WY, Chiang CW. Regulation of phosphorylation of Thr-308 of Akt, cell proliferation, and survival by the B55alpha regulatory subunit targeting of the protein phosphatase 2A holoenzyme to Akt. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1882–1892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler M, Gan L, Mazarei G, Graham RK, Liu L, Bissada N, et al. Phosphorylation of huntingtin at Ser421 in YAC128 neurons is associated with protection of YAC128 neurons from NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity and is modulated by PP1 and PP2A. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14318–14329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1589-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arregui L, Benitez JA, Razgado LF, Vergara P, Segovia J. Adenoviral astrocyte-specific expression of BDNF in the striata of mice transgenic for Huntington's disease delays the onset of the motor phenotype. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:1229–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9725-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Hayden MR, Xu B. BDNF overexpression in the forebrain rescues Huntington's disease phenotypes in YAC128 mice. J Neurosci. 2010;44:14708–14718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1637-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharami K, Xie Y, An JJ, Tonegawa S, Xu B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor over-expression in the forebrain ameliorates Huntington's disease phenotypes in mice. J Neurochem. 2008;105:369–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DA, Mehta RA, Lauterborn JC, Gall CM, Lynch G. Brief ampakine treatments slow the progression of Huntington's disease phenotypes in R6/2 mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt A, Carreton O, Lao-Peregrin C, Martin ED, Alberch J. Conditional BDNF release under pathological conditions improves Huntington's disease pathology by delaying neuronal dysfunction. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler VC, Auerbach W, White JK, Srinidhi J, Auerbach A, Ryan A, et al. Length-dependent gametic CAG repeat instability in the Huntington's disease knock-in mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:115–122. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt A, Rodrigo T, Martin ED, Gonzalez JR, Mila M, Cena V, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates the severity of cognitive alterations induced by mutant huntingtin: involvement of phospholipaseCgamma activity and glutamate receptor expression. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1234–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.