Abstract

Mature retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) do not normally regenerate injured axons and undergo apoptosis after axotomy. Inflammatory stimulation (IS) in the eye mediates neuroprotection and induces axon regeneration into the injured optic nerve. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) have been identified as key mediators of these effects. Here, we investigated the role of interleukin-6 (IL-6), another member of the glycoprotein 130-activating cytokine family, as additonal contributing factor. Expression of IL-6 was markedly induced in the retina upon optic nerve injury and IS, and mature RGCs expressed the IL-6 receptor. Treatment of cultured RGCs with IL-6 or specific IL-6 receptor agonist, significantly increased neurite outgrowth janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription-3 (JAK/STAT3) and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) dependently. Moreover, IL-6 reduced myelin, but not neurocan-mediated growth inhibition mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) dependently in cultured RGCs. In vivo, intravitreal application of IL-6 transformed RGCs into a regenerative state, enabling axon regeneration beyond the lesion site of the optic nerve. On the other hand, genetic ablation of IL-6 in mice significantly reduced IS-mediated myelin disinhibition and axon regeneration in the optic nerve. Therefore, IL-6 contributes to the beneficial effects of IS and its disinhibitory effect adds an important feature to the effects of so far identified IS-mediating factors. Consequently, application of IL-6 or activation of its receptor might provide suitable strategies for enhancing optic nerve regeneration.

Keywords: IL-6, CNTF, LIF, lens injury, inflammatory stimulation, axon regeneration, neuroprotection

Axonal injury in the adult central nervous system (CNS) is often associated with irreversible damage and loss of function owing to the limited capacity for neuronal network repair. Regenerative failure of injured axons has been related to inhibitory proteins that are associated with CNS myelin or the glial scar1, 2 and to an insufficient intrinsic ability of mature central neurons to re-grow injured axons.3, 4, 5 Therefore, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) do not normally regenerate axons after optic nerve injury, but, instead, undergo apoptotic cell death.6 However, RGCs can be transformed into an active regenerative state either by genetic modulation of the janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription-3 (STAT3) or the phosphatase and tensin homolog/phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway or by inflammatory stimulation (IS) in the eye of wild-type animals. RGCs are then able to survive injury and to re-grow axons into the inhibitory environment of the lesioned optic nerve.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Thus, IS exerts neuroprotective, axon growth promoting and significant disinhibitory effects. IS can be induced either by lens injury (LI)7, 8, 12, 13, 14 or by intravitreal application of crystallins15 or Toll-like receptor 2 agonists.16, 17, 18 Astrocyte-derived ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) have been identified as essential mediators of the neuroprotective and axon growth-stimulating effects of IS.16, 19, 20, 21 However, neither CNTF nor LIF exert disinhibitory effects, suggesting that additional factors contribute to IS-mediated optic nerve regeneration.22, 23

Interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as CNTF and LIF, belong to the family of glycoprotein 130 (gp130)-activating cytokines.24 IL-6 acts on target cells through a receptor complex composed of the full-length IL-6 receptor-α (IL-6Rα) and gp130.24 Alternatively, lL-6 can signal through a soluble IL-6 receptor.25, 26 In the healthy CNS, IL-6 expression is generally very low, but strongly upregulated after ischemia,27 trauma28, 29, 30 or in the peripheral nervous system after axotomy.31, 32 In this context, IL-6 has been shown to stimulate axon regeneration mainly by overcoming myelin-mediated inhibition.32, 33, 34, 35

We have found that IL-6 expression is markedly induced in the retina after optic nerve injury and IS. The current study therefore investigated the potential involvement of IL-6 as additional mediator of the beneficial effects of IS. We analyzed the expression of IL-6R in adult rat retinas and the response of RGCs to IL-6 exposure. Moreover, the effects of IL-6 application and genetic deletion on neurite growth on permissive and inhibitory substrates in culture as well as on optic nerve regeneration in vivo were examined. The data from this study demonstrate that IL-6 is another factor contributing to the beneficial effects of IS.

Results

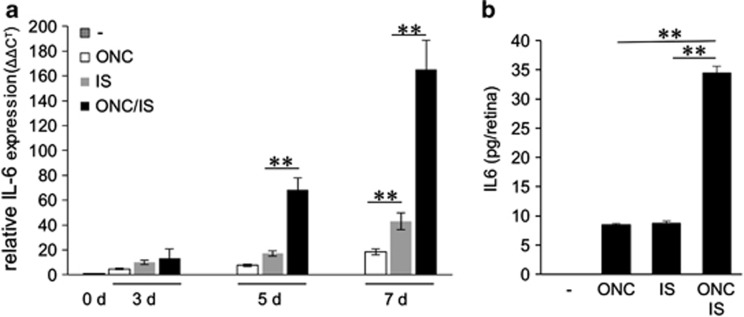

Optic nerve injury and IS increase retinal IL-6 expression

We measured IL-6 expression in retinas derived from untreated rats or from animals that were subjected to optic nerve crush (ONC), IS or ONC+IS using quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 1a). IL-6 mRNA was barely detectable in untreated controls. In comparison, IL-6 expression was slightly upregulated in retinas 3 days after ONC, IS or ONC+IS (Figure 1a). Expression was markedly induced in retinal tissues 5 days and even further increased 7 days after surgery with ONC+IS treatment showing the strongest expression (Figure 1a). Consistent with mRNA levels, IL-6 protein was detectable in retinal lysates 7 days after surgery with significant higher amounts after ONC+IS as determined by ELISA. No IL-6 protein was detected in untreated controls (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Inflammatory stimulation (IS) induces retinal IL-6 expression in rats. (a) Quantitative real-time PCR: IL-6 mRNA levels were quantified relative to GAPDH expression in adult untreated rat retinas (0 days (d)) and in retinas 3, 5 and 7 d after optic nerve crush (ONC) or after IS or after ONC+IS. Treatment effects: **P≤0.001. Reported values are means from three independent experiments. (b) ELISA: IL-6 protein levels were determined by ELISA in lysates from untreated retinas (−) or in retinas 7 days after ONC, IS or ONC+IS. No IL-6 was detected in control retinas. IL-6 expression was upregulated upon ONC and IS, but the significantly highest IL-6 levels were observed upon combination of the two treatments. Treatment effects: **P≤0.001

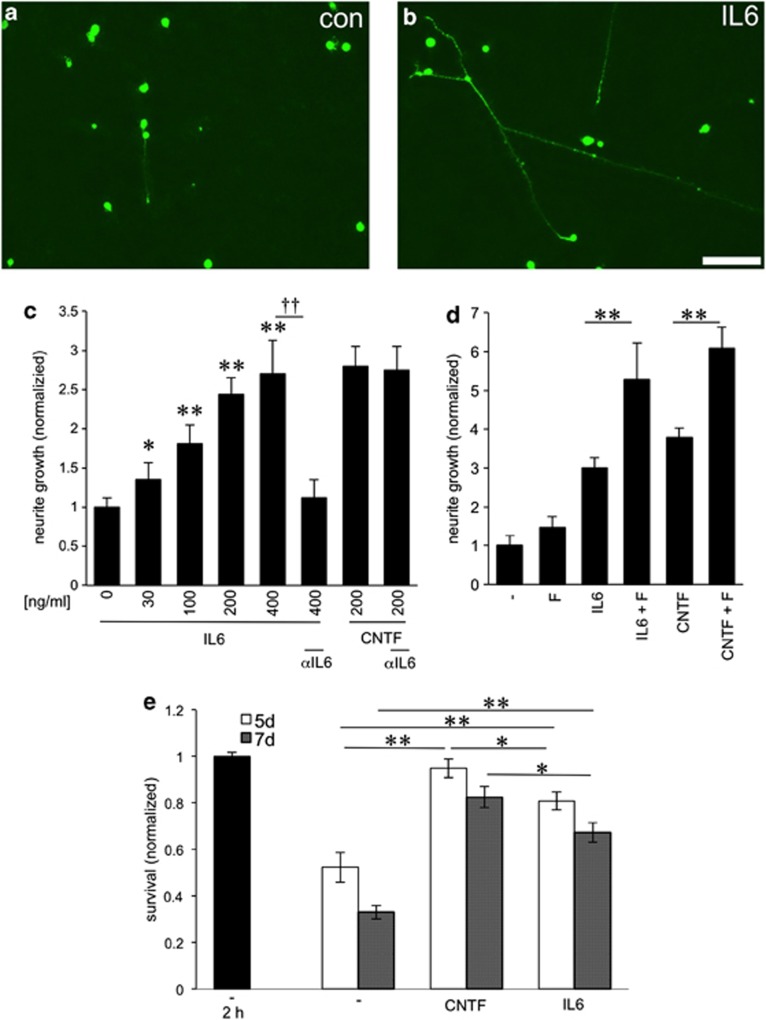

IL-6 promotes neuroprotection and neurite outgrowth of mature RGCs in culture

Using retinal cell cultures, we tested the effect of IL-6 on neurite outgrowth of mature RGCs on growth permissive substrate. RGCs were exposed to increasing concentrations of IL-6 (0, 30, 100, 200 and 400 ng/ml). CNTF (200 ng/ml), which reportedly stimulates axon growth of RGCs,19, 36, 37 was used as a positive control. IL-6 increased neurite growth in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 2a–c). Significant effects were measured at concentrations as low as 30 ng/ml and growth was maximal at ≥200 ng/ml IL-6, reaching effects comparable to CNTF treatment (Figure 2c). The presence of a bioactive IL-6 antibody in the cell culture medium completely blocked IL-6 stimulated, but not CNTF-mediated neurite outgrowth (Figure 2c). A control antibody (anti-α-parvalbumin) had no effect (data not shown). As shown previously for CNTF,37 the addition of forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase, further enhanced IL-6-stimulated neurite growth (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

IL-6 promotes neuroprotection and potent stimulation of RGC neurite growth in culture (a, b) βIII-tubulin-positive RGCs with regenerated neurites in culture 3 days after exposure to vehicle (con) (a) or IL-6 (200 ng/ml) (b). Scale bar: 50 μm. (c) Quantification of neurite growth of dissociated mature RGCs in the presence of increasing concentrations of IL-6 (ng/ml) and a bioactivity blocking IL-6-antibody (αIL6) as indicated. Values were normalized to untreated controls with an average neurite length of 4.5 μm/RGC. All concentrations tested were significantly different from the untreated control group. Incubation with CNTF (200 ng/ml) was used as a positive control. Reported values are means of three independent experiments. Treatment effects compared with untreated controls: *P≤0.01,**P≤0.001; antibody treatment effects: ††P≤0.001. (d) Quantification of neurite growth-promoting effects of IL-6 (200 ng/ml) or CNTF (200 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of forskolin (F). Values were normalized to the untreated control group with an average neurite length of 4.6 μm/RGC. (e) Number of surviving RGCs after 2 h, 5 d and 7 d in culture after exposure to vehicle (−), CNTF (200 ng/ml) or IL-6 (200 ng/ml). Values were normalized to RGC numbers after 2 h in culture without CNTF or IL-6 treatment with an average of 263 RGCs/well. Treatment effects within groups: *P≤0.01,**P≤0.001

We also quantified the number of surviving adult RGCs cultured for 3, 5 and 7 days (Figure 2e). Consistent with previous reports,36, 37 numbers of neurons did not yet decline after 3 days in culture (data not shown). However, RGC numbers in untreated cultures were markedly reduced after 5 and 7 days compared with the original number of RGCs (2 h) (Figure 2e). Treatment with IL-6 markedly increased the number of surviving RGCs after 5 and 7 days (Figure 2e), indicating a neuroprotective effect of IL-6. These effects were significantly lower than the neuroprotective effect achieved by CNTF treatment (Figure 2e).

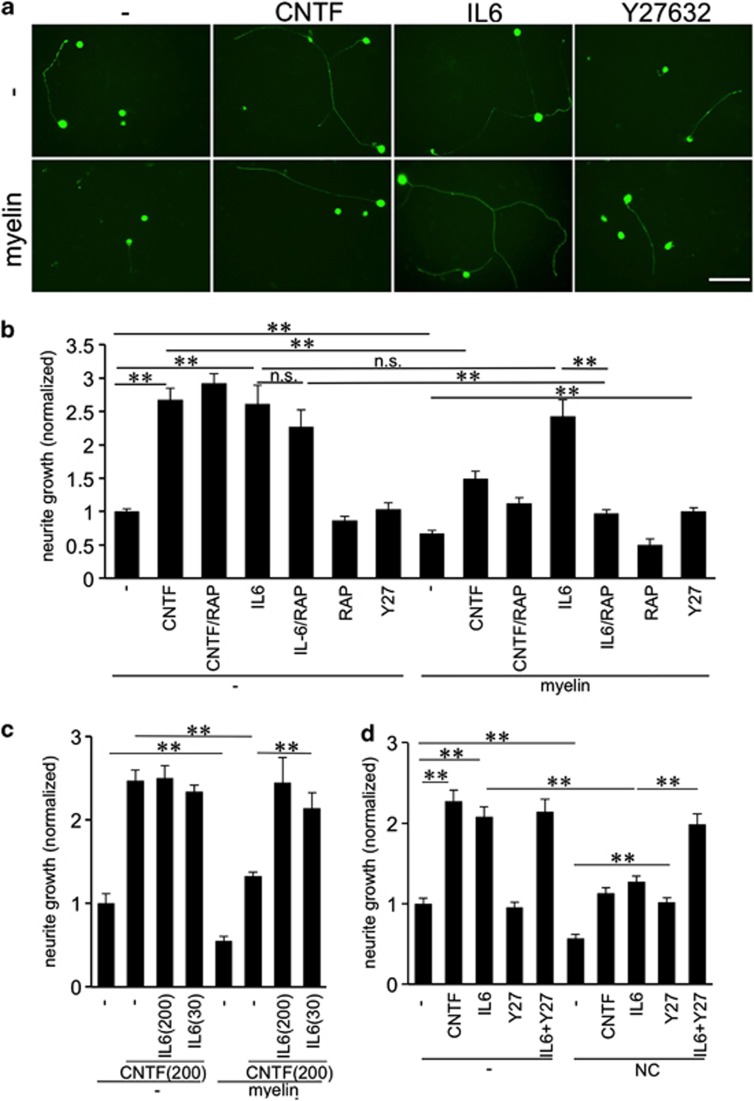

IL-6 overcomes myelin, but not neurocan-mediated neurite growth inhibition

We next investigated whether IL-6 may also affect neurite growth of mature RGCs on inhibitory substrates. To this end, we cultured adult rat RGCs in the presence of either CNS myelin extract (CME) or the inhibitory proteoglycan neurocan. Both CME and neurocan significantly reduced neurite growth of untreated controls and of CNTF-treated RGCs in comparison to neurite length on growth-permissive substrate (Figures 3a–d). Neurite outgrowth in the presence of IL-6, however, was not reduced by CME (Figures 3a and b). This disinhibitory effect of IL-6 was mTOR activity dependent as IL-6-induced neurite growth was markedly decreased in the presence of rapamycin (RAP; Figure 3b). Inhibition of mTOR activity by RAP had, however, no significant effect on axonal growth on laminin.

Figure 3.

IL-6 overcomes CME, but not neurocan-induced inhibition of RGC outgrowth. (a) βIII-tubulin-positive rat RGCs with regenerated neurites after exposure to vehicle (−), CNTF (200 ng/ml), IL-6 (200 ng/ml) or Y27632 (Y27) (40 μM) after 3 days in culture. The lower row of the depicted cultures was additionally exposed to CNS myelin extract (myelin). Scale bar: 50 μm. (b) Quantification of RGC neurite growth in cultures as in (a) plus groups that were additionally exposed to rapamycin (RAP) as indicated. Values were normalized to the untreated control group in the absence of myelin with an average neurite length of 7.2 μm/RGC. (c) Primary RGCs were treated with vehicle (−), CNTF (200 ng/ml) or CNTF+ IL-6 at 200 ng/ml or 30 ng/ml as indicated. Half of the cultures were additionally exposed to CNS myelin extract (myelin). Values were normalized to the untreated control group with an average neurite length of 6.6 μm/RGC. (d) Quantification of RGC neurite growth in cultures as in (a), but additionally exposed to the proteoglycan neurocan (NC; 5 μg/ml) instead of myelin. Values were normalized to the untreated control group with an average neurite length of 5.9 μm/RGC. Treatment effects: **P≤0.001, n.s.=nonsignificant

In contrast to CME, IL-6 could not overcome neurocan-mediated growth inhibition, as neurite length was reduced similarly as in CNTF-treated cultures (Figure 3d). Treatment with Y27632, a potent ROCK inhibitor, which blocks CME and neurocan-mediated inhibition restored neurite growth to control levels on permissive substrate (Figures 3a). Consequently, cultures exposed to IL-6 together with Y27632 showed similar neurite extension on growth permissive and inhibitory neurocan substrate (Figure 3d). The survival of RGCs was not affected by any of these treatments (Supplementary Figure 1a and c).

We next tested whether lower concentrations of IL-6 than needed for maximal neurite growth stimulation may be sufficient to overcome myelin inhibition. Co-treatment of cultures with CNTF (200 ng/ml) and IL-6 (200 ng/ml) did not enhance neurite growth on laminin further than CNTF alone (Figure 3c). In contrast, IL-6 overcame myelin inhibition on CNTF-treated RGCs when applied at 200 and 30 ng/ml, with outgrowth reaching similar levels as on laminin. These data demonstrate that the disinhibitory effect of IL-6 is achieved at lower concentrations than needed for maximal neurite growth stimulation (Figures 2c and 3c). The survival of RGCs was not affected by any of these treatments (Supplementary Figure 1b).

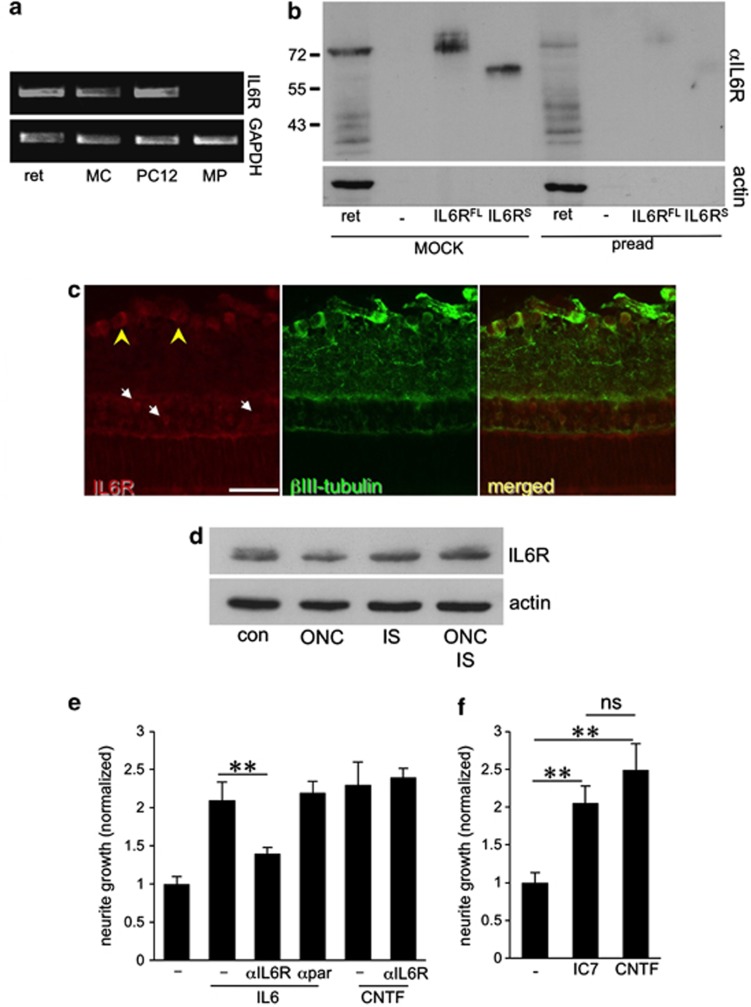

IL-6 receptor is expressed on mature RGCs and transmits the neurite growth stimulatory effects of IL-6

To investigate whether IL-6 might mediate its growth-stimulatory effect through its cognate receptor, we analyzed the expression of the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) in the retinal system (Figure 4). First, we performed RT-PCR on RNA isolated from adult rat retinas, peritoneal macrophages and a Müller cell line (rMC1), using PC12 cells as positive control. IL-6R was detected in the rat retina and rMC1 cells, but not in peritoneal macrophages (Figure 4a). Western blot analysis verified the expression of IL-6R protein in the adult rat retina (Figure 4b). The IL-6R-specific band at ∼75 kDa was the same size as recombinantly expressed full-length IL-6R. The soluble form of IL-6Rs (∼55 kD) was not detectable in retinal lysates (Figure 4b). The specificity of the IL-6R signal was verified using IL-6R antibody preabsorbed to lysates from IL-6R overexpressing cells, which strongly reduced western blot detection (Figure 4b, pread). Immunohistochemical analysis of retinal cryosections showed positive IL-6R staining in RGCs and cells in the inner nuclear layer (Figure 4c). This staining was again strongly reduced by antibody preadsorption (data not shown). Retinal IL-6R expression remained unchanged 5 days after ONC, IS or ONC+IS as determined by western blot analysis (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

IL-6 stimulates neurite growth via the IL-6 receptor. (a) RT-PCR demonstrating the expression of full-length IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) in the adult rat retina (ret), and the rMC-1 Müller cell line (MC), but not in primary macrophages (MP). PC12 cells endogenously expressing IL-6R served as positive control. RT-PCR of the housekeeping gene GAPDH verified equal amounts of template cDNA. (b) Western blot analysis detects endogenous IL-6R protein in the adult retina at the same molecular weight as full-length IL-6R (IL-6RFL), but not soluble IL-6R (IL-6RS) overexpressed in HEK293 cells. Preadsorption of the antibody with HEK cell lysate expressing IL-6R (pread) specifically diminished IL-6R antibody reactivity. (c) Immunohistochemical staining of adult rat retina sections with anti-IL-6R antibody (red) and anti-βIII-tubulin antibody (green). RGCs (yellow arrowheads) and other cells in the inner nuclear layer (white arrows) were positively stained with IL-6R antibody. Scale bar: 50 μm. (d) Western blot: Retinal lysates were generated without treatment (con), or 5 days after optic nerve crush (ONC), inflammatory stimulation (IS) and ONC+IS. The expression of IL-6R is similar for all these treatments. Actin served as loading control. (e, f) Quantification of neurite growth of dissociated primary RGCs: (e) the presence of anti-IL-6R antibody (αIL6R), but not the control antibody against α-parvalbumin compromised the neurite outgrowth-promoting effects of IL-6, but not of CNTF. Values were normalized to the untreated control group with an average neurite length of 7.3 μm/RGC. (f) IC7, a specific IL-6R agonist, stimulates neurite growth to a similar extent as CNTF. Values were normalized to neurite growth in untreated RGC cultures (−) with an average neurite length of 5.9 μm/RGC. Treatment effects: **P≤0.01. n.s.: nonsignificant

We next investigated whether the neurite growth-promoting effect of IL-6 as mediated via IL-6R. IL-6-induced outgrowth of RGCs was markedly reduced in the presence of a bioactive IL-6R antibody, but not by an anti-α-parvalbumin control antibody (Figure 4e). The survival of RGCs in these cultures was not affected (data not shown). In addition, the designer cytokine IC7 that exclusively binds to IL-6R,38, 39 induced neurite growth comparable to IL-6 application (Figure 4f). These results indicate that IL-6R stimulation is sufficient to promote neurite growth of primary mature RGCs.

IL-6 stimulated neurite growth depends on the activation of the JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

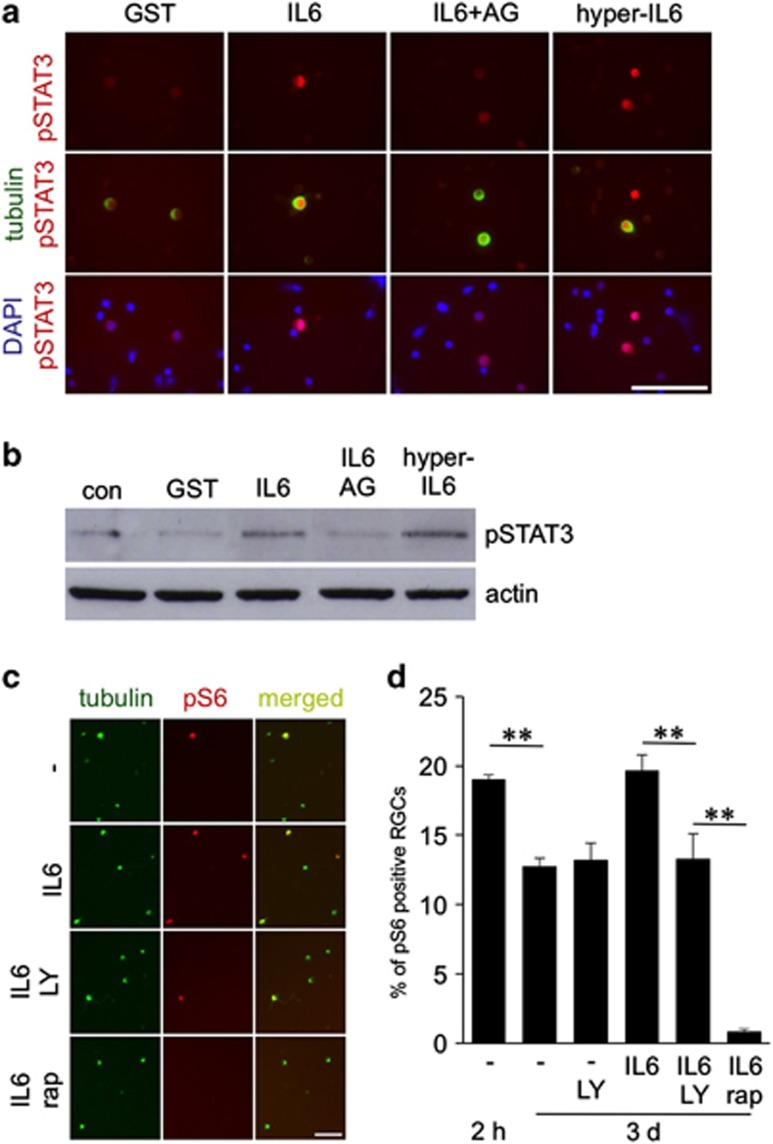

To test whether IL-6 indeed activates IL-6R-specific signaling pathways in primary adult RGCs, we added either recombinant GST, IL-6 or IL-6 together with the JAK/STAT3 pathway inhibitor AG490 to the medium of unprimed dissociated retinal cells for 15 min. We then analyzed the phosphorylation of STAT3 by immunohistochemistry and western blot (Figures 5a and b). Hyper-IL-6, which directly binds to and activates gp130,37, 40 was used as a positive control. IL-6 and hyper-IL-6 treatment induced pronounced upregulation of STAT3 phosphorylation in comparison to control cultures treated with recombinant GST protein within 15 min. This increase in STAT3 phosphorylation was specifically blocked in the presence of AG490 (Figures 5a and b), suggesting direct activation of the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway by IL-6.

Figure 5.

IL-6 activates the JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways in RGCs. (a) Retinas of adult rats were dissociated and cultured in the presence of recombinant control protein (GST, 200 ng/ml), IL-6 (IL-6; 200 ng/ml), IL-6+JAK inhibitor AG490 (AG) or hyper-IL-6 (hyper-IL6, 200 ng/ml) for 15 min and then immunocytochemically stained for phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; red) and βIII-tubulin (green). Nuclei of cells were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) Western blot analysis. Levels of pSTAT3 were detected in dissociated retinal cell cultures after exposure to GST, IL-6, IL-6+AG or hyper-IL-6 for 15 min. Detection of β-actin ensured loading of equal amounts of protein per lane. (c) βIII-Tubulin-positive RGCs (green) were positively stained for phosphorylated S6 (pS6, red) after 3 days in culture and exposure to vehicle (−), IL-6, LY-294002 (LY) and rapamycin (RAP) as indicated. Scale bar: 50 μm. (d) Quantification of pS6-positive RGCs after 2 h or 3 days in culture and exposure to IL-6, LY-294002 (LY) and RAP as indicated. Treatment effects: **P≤0.001

In addition, we investigated whether IL-6 affects the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in mature RGCs by quantifying the number of pS6-positive RGCs as described previously.11, 23 About 19% of untreated rat RGCs were pS6-positive after 2 h in culture and this proportion decreased to 13% after 3 days (Figures 5c and d). In contrast, IL-6-treated RGCs maintained the original pS6 level observed after 2 h even after 3 days (∼19%). This effect was abrogated in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (∼14% pS6-positive cells), suggesting that IL-6 activates this signaling pathway to modulate mTOR activity. Cultures treated with RAP, a potent mTOR inhibitor, showed very few remaining pS6-positive RGCs (∼1% Figures 5c and d).

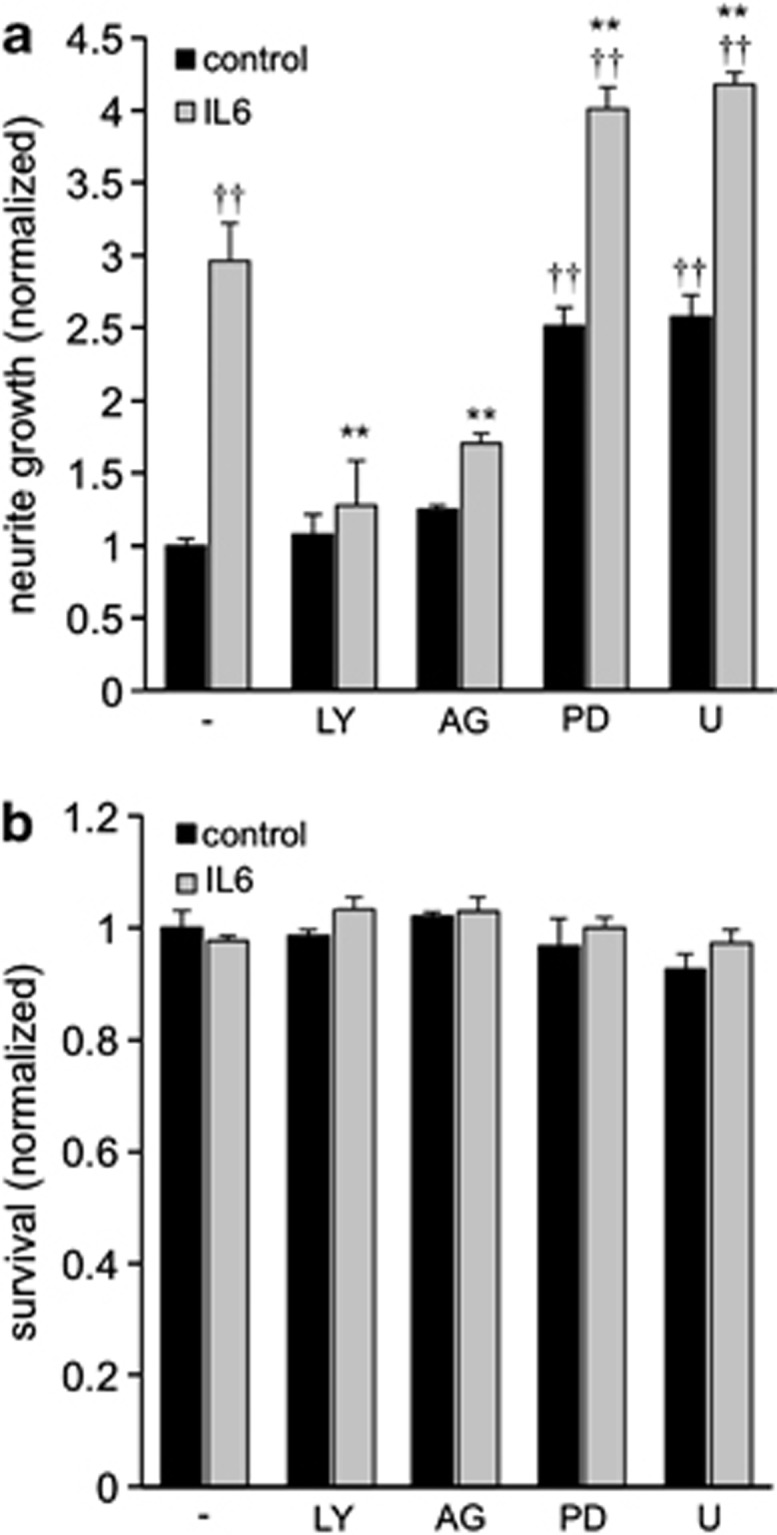

We next tested whether these activated signaling pathways contributed to IL-6-induced neurite outgrowth stimulation. Indeed, application of AG490 (JAK/STAT3) or LY294002 (PI3K/Akt) to retinal cultures abrogated the growth-promoting effect of IL-6, without affecting outgrowth in untreated control groups (Figure 6a). As previously reported for CNTF23, inhibition of mTOR by RAP did not significantly reduce RGC neurite growth on a permissive substrate (Figure 3b). The two mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 enhanced neurite outgrowth in untreated controls and additionally increased IL-6-induced neurite extension (Figure 6a), as was previously shown for CNTF.37 The survival of RGCs in these cultures was not significantly affected by either treatment (Figure 6b). Altogether, these data suggest that activation of JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt are necessary for IL-6-mediated neurite growth stimulation.

Figure 6.

Neurite growth-promoting effects of IL-6 are dependent on JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt pathways. (a) Quantification of neurite growth of RGCs 3 days after treatment of retinal cultures with vehicle (−), LY294002 (LY), AG490 (AG), PD98059 (PD) or U0126 (U) together with IL-6 (gray bars) or without IL-6 (black bars). Data were normalized to values of the control group (−) with an average neurite length of 6.1 μm/RGC. Treatment effects were either compared with the group treated with IL-6 only: **P≤0.001; or with the no treatment control group: ††P≤0.001. (b) Quantification of RGC survival of the groups presented in (a) normalized to the control group (1334 RGCs/well)

Intravitreal injection of IL-6 activates STAT3 and transforms RGCs into a regenerative state

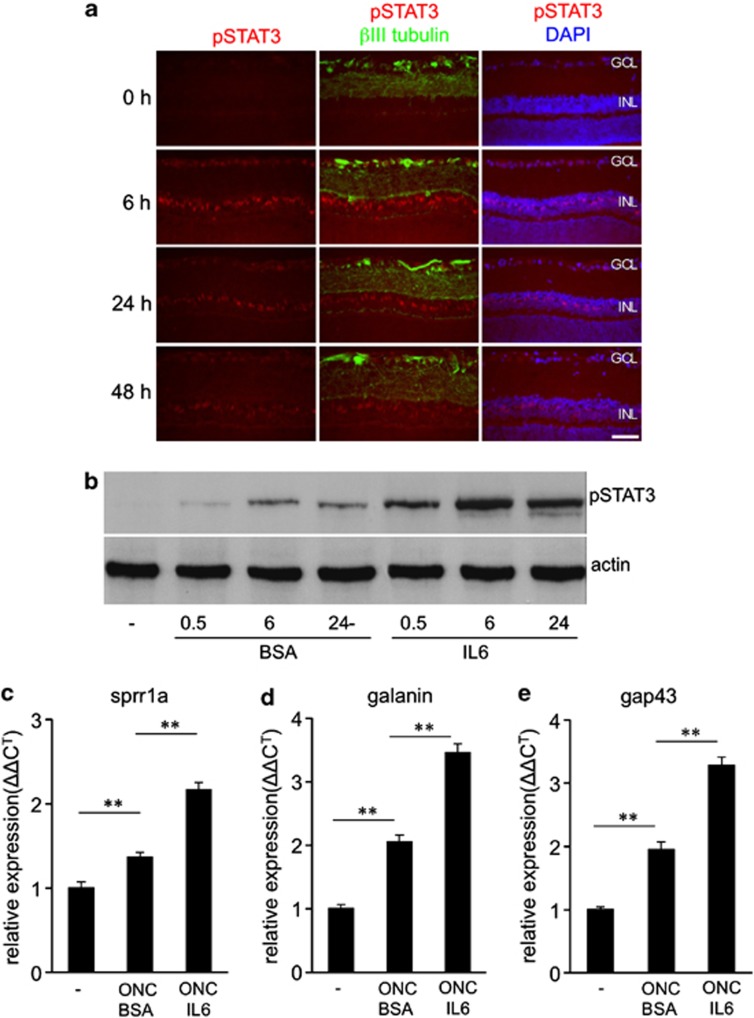

We next tested how increased IL-6 levels might affect retinal cells in vivo. IL-6 or bovine serum albumin (BSA) control protein was injected intravitreally after ONC and the level of phosphorylated STAT3 was analyzed by immunohistochemistry and western blotting. In comparison to BSA controls, IL-6 activated the JAK/STAT3 pathway as indicated by increased pSTAT3 staining in RGCs and cells of the inner nuclear layer within the first 6 h after injection (Figures 7a and b). Western blot analysis confirmed increased pSTAT3 levels in IL-6- compared with BSA-injected retinas (Figure 7b). The pSTAT3 signal somewhat declined at 24 and 48 h post injection (Figure 7a), potentially due to the induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) expression, which functions as a negative feedback loop for this pathway.41 Moreover, mRNA levels of the regeneration-associated genes Sprr1a, Galanin and Gap-43 were significantly increased in IL-6-injected retinas compared with BSA treated controls, suggesting that RGCs were transformed into a regenerative state (Figure 7c–e).

Figure 7.

Intravitreally applied IL-6 activates the JAK/STAT3 pathway in RGCs and cells of the inner nuclear layer. (a) Immunohistochemical staining of retinal sections from axotomized rats for pSTAT3 (red) and βIII-tubulin (green) 0, 6, 24 and 48 h after intravitreal injection of IL-6. The nuclei of cells were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer. (b) Western blot analysis of retinal lysates for phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) levels 0.5, 6 and 24 h after intravitreal injection of IL-6. BSA injections were used as controls. Highest levels of pSTAT3 were measured 6 h after intravitreal application of IL-6. Actin served as loading control. Experiments were performed on at least three different animals per group. (c–e) Quantitative real-time PCR of retinas from axotomized rats that received intravitreal administration of either IL-6 or BSA. IL-6 induced the expression of the regeneration-associated genes Sprr1a (c), Galanin (d) and Gap43 (e). Treatment effects: **P≤0.001

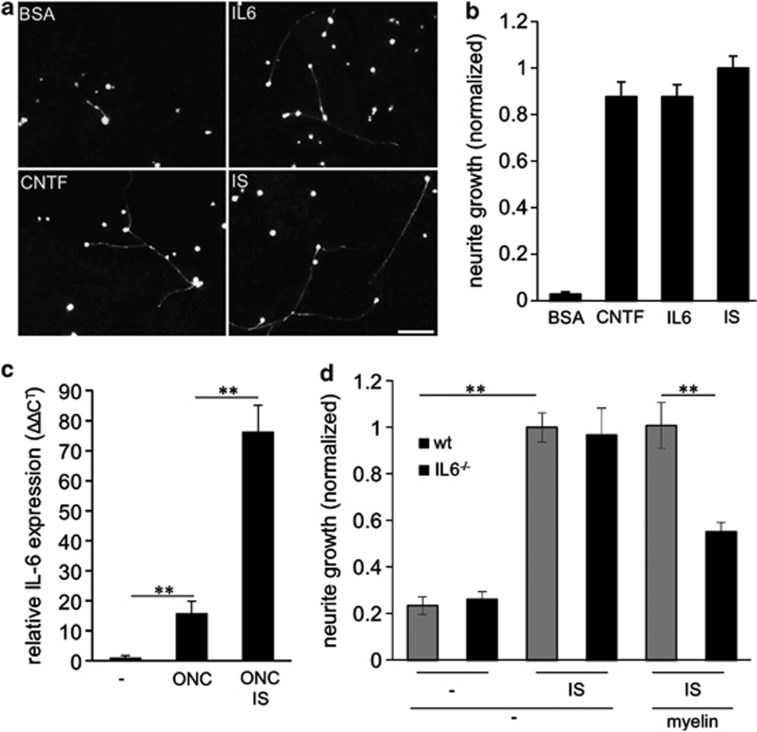

To functionally test whether intravitreally applied IL-6 transformed RGCs into a regenerative state, we prepared retinal cultures 5 days after ONC and IL-6 or BSA injections. Positive control groups were subjected to ONC+CNTF injection or to ONC+IS treatment, which have previously been shown to transform RGCs into a potent regenerative state.20, 37 Consistent with these earlier reports, intravitreal control injections with BSA resulted in only weak spontaneous neurite outgrowth after 24 h in culture. IL-6, CNTF and IS treatment, however, strongly stimulated RGC neurite outgrowth to similar extent (Figures 8a and b), indicating that IL-6 application transforms RGCs into a regenerative state.

Figure 8.

Intravitreally applied IL-6 transforms RGCs into a regenerative state and endogenous IL-6 expression is required for inflammatory stimulation (IS)-mediated disinhibition in mice. (a) Dissociated rat retinal cell cultures immunostained with βIII-tubulin antibody, showing regenerating RGCs after 24 h in culture. Optic nerves of all animals were intraorbitally crushed 5 days prior culturing and eyes concomitantly received either intravitreal injections of BSA (1.5 μg), IL-6 (1.5 μg) or CNTF (1.5 μg) or an IS. Scale bar: 50 μm. (b) Quantification of neurite growth normalized to values from the group treated with ONC+IS with an average neurite length of 8.6 μm/RGC. Four animals were analyzed per treatment group. (c) Quantitative real-time PCR of adult mouse retinas. IL-6 expression levels were quantified relative to GAPDH expression of untreated eyes (–) and in retinas 5 days after optic nerve crush (ONC) or ONC + IS. Reported values are means from three independent experiments. (d) Quantification of neurite growth of dissociated RGCs from wild-type or IL-6-deficient mice cultured either in the absence or presence of myelin after 24 h in culture. All animals had received a conditional ONC , while some had additional IS 5 days prior to culturing to determine the regenerative state. At least three animals were analyzed per treatment group. Values were normalized to values received from wild-type group treated with ONC+IS and cultured in the absence of myelin with an average neurite length of 4.6 μm/RGC. Treatment effects: **P≤0.001

IL-6 facilitates axon growth in the optic nerve

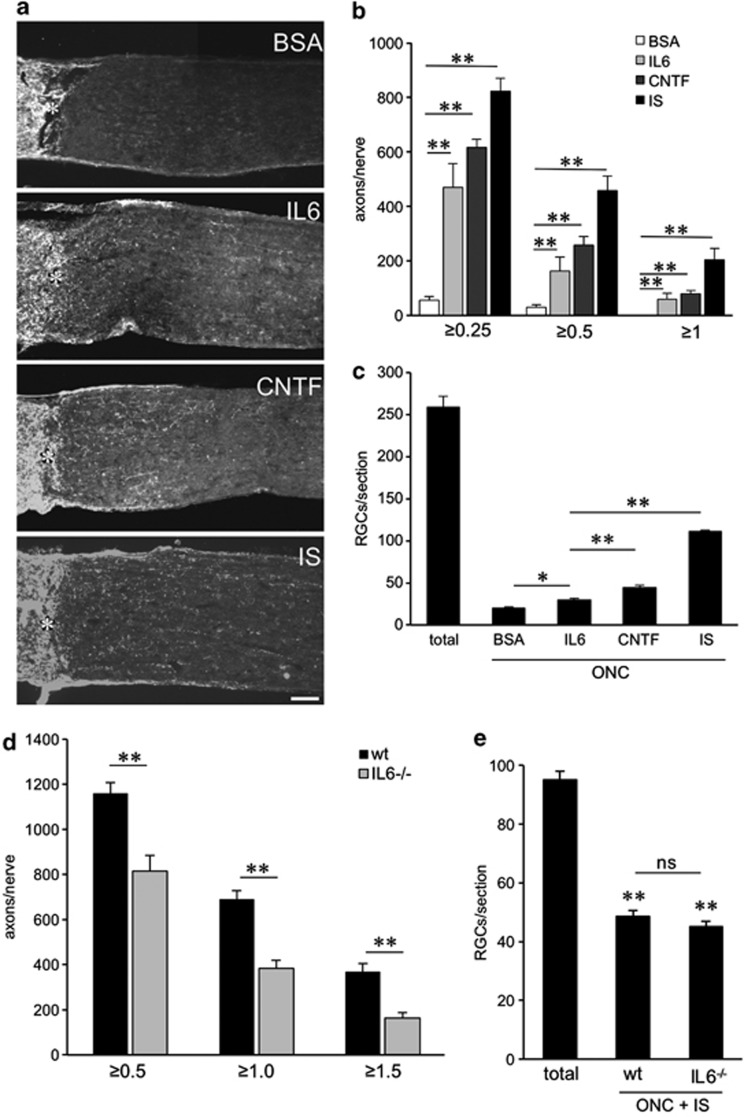

To explore whether IL-6 expression might contribute to the beneficial effects of IS in vivo, we used IL-6-deficient mice (IL6−/−; Figure 8d, Figures 9d and e). Quantitative real-time PCR verified that retinal IL-6 expression is also upregulated in wild-type mice upon ONC and IS (Figure 8c). Wild-type and IL6−/− mice were then subjected to ONC+IS. The regenerative state of RGCs was evaluated by quantifying spontaneous neurite outgrowth in cultures 5 days after surgery as described previously.19, 20 Interestingly, outgrowth of untreated (−) and primed (IS) RGCs from wild-type and IL-6-deficient animals showed no differences on a growth permissive substrate (laminin; Figure 8d). However, outgrowth of RGCs from IL-6-deficient animals was significantly reduced on myelin (Figure 8d). The survival of RGCs in these cultures was not affected by any of these treatments (data not shown). These data suggest that IL-6 is not mainly involved in the initial transformation of RGCs into a regenerative state upon IS, but that it may facilitate axon growth in the inhibitory environment of the optic nerve, thereby contributing to enhanced regeneration. To test this possibility, we quantified the number of axons regenerating into the optic nerve 14 days after ONC+IS in wild-type and IL6−/− mice (Figure 9d). The amount of regenerating axons was significantly reduced at various distances from the ONC site in IL6−/− mice compared with wild-type controls, confirming that IL-6 deficiency compromises IS-induced axonal regeneration in the optic nerve. RGC numbers on retinal sections were comparable in wild-type and IL6−/− animals (Figure 9e), indicating that the neuroprotective effect of IS was mainly mediated by factors other than IL-6.19 Repeated injections of CNTF into the vitreous body are sufficient to delay the degeneration of RGCs and to promote axon regeneration into the optic nerve.10, 20, 42, 43, 44 We therefore tested if IL-6-injections can exert similar effects. For this purpose, we performed ONC in rats and concomitantly injected recombinant IL-6 protein. BSA and CNTF injections or IS served as negative and positive controls, respectively. The number of regenerating axons and the survival of RGCs (RGCs/retinal section) were analyzed 2 weeks later (Figures 9a–c). IL-6 and CNTF caused comparable growth of RGC axons into the distal optic nerve, whereas IS induced regeneration was significantly stronger (Figures 9a and b). In contrast, the number of surviving RGCs detected on retinal sections was significantly lower in IL-6-injected animals in comparison to CNTF and IS treatment (Figure 9c). Therefore, IL-6 seems to confer, at least at the concentrations tested, less neuroprotection on axotomized RGCs than CNTF in vivo, but nevertheless potently induces axonal regeneration.

Figure 9.

Intravitreally applied IL-6 stimulates axon regeneration in the crushed rat optic nerve in vivo, whereas effects of inflammatory stimulation (IS) are significantly reduced in IL-6 deficient compared with wild-type mice. (a) Longitudinal sections through the optic nerve were stained with an anti-Gap43 antibody 2 weeks after optic nerve crush (ONC)+two intravitreal injections of BSA (1.5 μg), ONC+two intravitreal injections of IL-6 (1.5 μg), ONC+two intravitreal injections of CNTF (1.5 μg) or ONC+IS. Scale bar=100 μm. Asterisks indicate the injury site. (b) Quantification of axon regeneration into the rat optic nerve ≥0.25, ≥0.5 and ≥1 mm distal to the lesion site for the experimental conditions described in a. Five to eight animals were analyzed per treatment group.(c) Quantification of surviving βIII-tubulin-positive RGCs in eye sections from the same groups as described in a. At least six sections from five to eight different animals were analyzed per treatment group. Total=number of RGCs in naive retina. Treatment effects: **P<0.001, compared with the group treated with ONC+BSA. (d) Quantification of axon regeneration (number of axons growing ≥0.5, ≥1 and ≥1.5 mm beyond the injury site) per optic nerve in wild-type (wt) and IL-6-deficient (IL6−/−) mice 2 weeks after ONC+IS. At least six animals were used per treatment group. The number of regenerating axons is significantly reduced in IL-6-deficient mice. Treatment effect: **P<0.001. (e) Quantification of surviving RGCs (RGCs per retinal cross section) of the same eyes as described in d. At least six sections each from six different animals were analyzed per treatment group. Total=number of RGCs in naive retina. Treatment effects compared with total RGCs: **P<0.001; n.s.: nonsignificant

Discussion

IL-6 is a neuroprotective and potent neurite growth-promoting factor for mature RGCs

IL-6 can contribute both to injury and repair processes in the CNS depending on the pathological context.45, 46 The current study demonstrates that IL-6 is neuroprotective to mature RGCs, although weaker compared with CNTF. Furthermore, IS-mediated neuroprotection was unchanged in IL6−/− mice (shown in the current study), whereas it was abolished in CNTF/LIF double knockout mice compared with control wild-type animals.19 Together, these data suggest that most of IS-induced neuroprotection is mediated by CNTF and LIF rather than IL-6.

However, consistent with a recently published study47 we found that IL-6 can stimulate neurite growth of RGCs with similar efficacy as CNTF. This effect was concentration dependent reaching maximal growth at ≥200 ng/ml, which is comparable to the active concentrations reported previously for dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons.32 Likewise, intravitreal application of IL-6 induced axon regeneration beyond the lesion site of the optic nerve to similar extent as CNTF.

The neurite growth-promoting effect of IL-6 was mediated via the IL-6R, which was found to be expressed in RGCs. Consistently, RGCs responded within minutes to IL-6 treatment by JAK/STAT3 pathway activation and IL-6-stimulated neurite growth was blocked by an IL-6R antibody. Moreover, IC7, a designer cytokine that exclusively binds to IL-6R,38 also triggered neurite growth stimulation. Therefore, IL-6R may be a suitable pharmacological target for axonal growth stimulation of injured RGCs.

Downstream of IL-6R the JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/AKt/mTOR pathways, which have previously been shown to be important for regenerative axon growth9, 48 were activated in RGCs and their inhibition blocked IL-6 mediated growth stimulation. These same pathways are stimulated upon CNTF application23, 37 and similar to CNTF, co-application of forskolin further enhanced IL-6-stimulated neurite outgrowth. Increased cAMP levels have been shown to suppress the upregulation of SOCS3, a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT3 pathway, and might thereby release the intrinsic cellular brake.44

IL-6 desensitizes RGCs toward myelin inhibition

Consistent with previous studies that used other types of neurons,32, 33, 34 we found that IL-6 treatment could overcome myelin-induced neurite growth inhibition in cultured RGCs and that this effect was mTOR activity dependent. Interestingly, this disinhibitory activity of IL-6 was effective at lower concentrations than required for axon growth stimulation as 30 ng/ml of IL-6 were sufficient to reach maximum disinhibition on inhibitory myelin substrate. The exact mechanism of this disinhibition still needs to be elaborated. As IL-6 was insufficient to block neurocan-mediated growth inhibition, IL-6 probably affects molecular processes upstream of RhoA/ROCK signaling. Consistently, treatment of RGC cultures with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 or with Taxol overcame myelin as well as neurocan-mediated neurite growth inhibition.22, 36, 49 This disinhibitory effect discriminates IL-6 from CNTF, as myelin-induced neurite growth inhibition is unaffected by CNTF treatment (this study and 22, 23, 36).

IL-6 contributes to IS-mediated optic nerve regeneration

Expression of IL-6 in the CNS remains low under normal conditions, but it is markedly upregulated after ischemia27 or trauma28, 29, 30 and in the peripheral nervous system after axotomy.31, 32 Accordingly, we did not find significant IL-6 mRNA or protein expression in the naïve adult retina. IL-6 levels were induced after optic nerve injury, similar to IL-6 upregulation after elevation of intraocular pressure47, 50 or axotomy in the peripheral nervous system.31, 32 However, strongest induction of IL-6 expression was measured after ONC and additional IS. Immunohistochemical detection of IL-6 is very challenging as it is a secreted cytokine,50 but retinal astrocytes, microglia and even RGCs have been shown to express IL-6 upon ONC or after elevation of intraocular pressure.47, 51 Considering that even low amounts of IL-6 released by RGCs themselves or by adjacent cells might be effective on RGCs, it would be arduous to clearly distinguish whether glial, microglia/macrophage or neuron-derived IL-6 contributes to axon regeneration. Nevertheless, our quantitative data demonstrate that retinal IL-6 mRNA and protein expression are clearly elevated upon ONC and IS and that IL-6 deficiency reduces IS-mediated axon regeneration in the optic nerve in vivo and neurite growth on inhibitory myelin substrate in vitro.

Intravitreal administration of exogenous IL-6 simultaneously with optic nerve injury induced regeneration-associated genes such as Sprr1a, Gap43 and Galanin52 and promoted axon growth. Whether IL-6 causes aberrant axon growth as recently reported for CNTF53 has not been investigated in the current study. Nevertheless, the initial transformation of RGCs into a regenerative state upon IS still appears to be mainly mediated by LIF and CNTF as neither neuroprotective nor axon growth-promoting effects were seen in CNTF/LIF double knockout animals19 and, consistently, neuroprotection was not compromised in IL6−/− mice. These findings could be explained by the relatively late onset of IL-6 expression in the retina after ONC and the observation that disinhibitory effects of IL-6 were reached at lower concentrations in the presence of CNTF than necessary for axon growth stimulation alone (Figure 3c). In contrast to CNTF, whose expression is already increased 1–2 days after ONC+IS and correlated with RGCs entering the regenerative state (starting 2 days after ONC+IS)20, 52 IL-6 levels were still low 3 days after ONC+IS and continued to increase 5 days post injury. Thus, the beneficial effects of IL-6 may become most effective at later stages after IS. Consistently, CNTF/LIF double knockout mice showed slight STAT3 activation 5 days after ONC+IS19, which might have been induced by endogenous IL-6. These initially low IL-6 levels were, however, obviously insufficient to switch RGCs into an active regenerative state in the absence of CNTF and LIF.19 In support of this notion, spontaneous neurite outgrowth of RGCs from IL-6-deficient and wild-type mice showed no difference. However, RGCs of IL6−/− animals displayed significantly reduced outgrowth on myelin in comparison to wild-type animals, suggesting that IL-6 is necessary for the disinhibitory effects of IS. Thus, IL-6 expression may facilitate axon growth in the inhibitory environment of the optic nerve and, as shown in the current study, its absence in IL6−/− mice resulted in reduced regeneration upon IS.

As IL-6 reportedly enhances axon regeneration of DRGs in vivo,32, 34 it might have also potentially contributed to inflammation-induced preconditioning of DRGs in vivo by zymosan.54 The underlying mechanisms of this effect are still unclear as oncomodulin treatment was insufficient to mimic the effects of zymosan treatment.55

In conclusion, IL-6 contributes to IS-mediated optic nerve regeneration. In comparison with CNTF, IL-6 exerts myelin-disinhibitory effects, thereby bringing an important feature relevant for successful axonal regeneration to the set of known factors involved in IS. Therefore, IL-6R might be a potentially important new target for pharmacological intervention to promote optic nerve regeneration.

Materials and Methods

ONC, LI and intravitreal administration

Surgical procedures were approved by the local authorities (Regierungspräsidium Tübingen) and performed as described previously.19, 56 In brief, adult female Sprague–Dawley rats (weighing 200–230 g) or female IL-6 knock-out mice (B6.129S2-IL-6tm1Kopf/J, Jackson laboratories; 20–25 g) or corresponding wild-type mice were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. All animals were housed under the same conditions for at least 10 days before being used in experiments. Animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (60–80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10–15 mg/kg), and a 1- to 1.5-cm incision was made in the skin above the right orbit. The optic nerve was surgically exposed under an operating microscope; the dural sheath was longitudinally opened. The nerve was completely crushed 1 mm behind the eye for 10 s using jeweler's forceps, avoiding injury to the retinal artery. The vascular integrity of the retina was verified by fundoscopic examination after each surgery.

For the evaluation of the regenerative state of RGCs in cell cultures, rats received intravitreal injections either of BSA (1500 ng; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), CNTF (1500 ng; Serotec, Oxford, UK) or IL-6 (1500 ng; Serotec) solution concomitantly with and again 3 days after optic nerve injury. After 5 days, rats were killed to either extract retinal RNA (three retinas per case) or to prepare retinal cell cultures, which were kept for another 24 h. Each experiment was independently repeated at least twice. For evaluating the regenerative state of murine RGCs, wild-type or IL6−/− mice received ONC while some received additional IS. Mice were killed after 5 days for cell culture preparation and retinal cells were cultured for 24 h. Each experiment with mice was independently repeated at least three times. For evaluating in vivo regeneration in the optic nerve, rats received two intravitreal injections of BSA, CNTF or IL-6 (concentrations see above) 3 and 7 days after optic nerve surgery. We did not perform additional injections due to the potential risk of damaging the lens. IS was induced by LI using a retrolenticular approach, puncturing the lens capsule with the tip of a microcapillary tube as described previously.7 IS was supported by intravitreal injections of phosphate-buffered saline (10 μl) after retrieving the same volume from the anterior chamber of the eye. Each experimental group consisted of at least five rats or mice.

Dissociated retinal cell cultures and immunohistochemical staining

Dissociated retinal cultures were prepared as described previously.57 In brief, tissue culture plates (4-well plates; Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) were coated with poly-𝒟-lysine (0.1 mg/ml, molecular weight<300 000 Da; Sigma), rinsed with distilled water and then air-dried. In experiments without prior treatment of animals in vivo wells were additionally coated with laminin (20 μg/ml; Sigma). To prepare low-density retinal cell cultures, untreated or in vivo pretreated rats or mice were killed by an overdose of chloralhydrate solution (14%). Retinas were rapidly dissected from the eyecups and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a digestion solution containing papain (16.4 U/ml; Worthington; Katarinen, Germany) and ℒ-cysteine (0.3 μg/ml; Sigma) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Retinas were then rinsed with DMEM and triturated in 2 ml DMEM. To remove cell fragments or factors released from the cells the cell suspension of one retina was immediately adjusted to a volume of 50 ml with DMEM and centrifuged for 5 min, at 200 × g. The pellet was carefully resuspended in 7 ml (rats) or 2 ml (mice) of DMEM containing B27-supplement (Invitrogen; 1 : 50) and penicillin/streptomycin (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) (1 : 50). Dissociated cells were passed through a cell strainer (40 μm, Falcon) and 300 μl of cell suspension were added into each well resulting in a dispersion of cells at low density. Cultures were arranged in a pseudo-randomized manner on the plates so that the investigator would not be aware of their identity. Retinal cells were cultured for either 24 or 72 h and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma). They were then processed for immunocytochemical staining.

To test the effects of IL-6 or signaling pathway inhibitors in vitro, dissociated cell cultures of untreated retinas were prepared and IL-6 was added to the medium at the following concentrations: 0, 30, 100, 200 and 400 ng/ml. Forskolin (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 15 μM either alone or in combination with CNTF (200 ng/ml) or IL-6 (200 ng/ml). A bioactive anti-IL-6 antibody (Biosource, ARC0962, Paisley, UK) was added at a concentration of 5 μg/ml, an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 5 μg/ml, an anti-α-parvalbumin antibody (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA) at 5 μg/ml, the JAK2 inhibitor AG490 (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) at 5 μM, the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (Sigma) at 1 μM, RAP (LC-Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA) at 10 nM. The two MAP-kinase inhibitors PD98059 (Calbiochem) and U0126 (Calbiochem) were added at a final concentration of 5 μM. All inhibitors were applied either alone or together with IL-6 (200 ng/ml). In experiments that assessed the effect of IL-6 on CME inhibition, the final CNTF and IL-6 (both Serotec) concentrations were adjusted to 200 ng/ml and 30 ng/ml. Y27632 (Sigma) was used at a concentration of 40 μM. Inhibitory CME was obtained according to previously published work36, 58 and added to cultures at a preoptimized concentration of ∼10 μg/ml and preoptimized neurocan (R&D Systems) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml.23

For studying the effect of IL-6 and CNTF on RGC survival (Figure 2e), 50 μl of the cell suspension were added into 96-well culture plates coated with poly-𝒟-lysine (0.1 mg/ml, molecular weight<300 000 Da; Sigma). Retinal cultures were either untreated or treated with CNTF (200 ng/ml) or IL-6 (200 ng/ml) and fixed after 2 h, 3 d, 5 d or 7 d in culture.

After fixation with 4% PFA, cells were prepared for immunocytochemical staining with a βIII-tubulin-antibody (TUJ-1; (Babco, Richmond, CA, USA; 1 : 2000). βIII-tubulin is a phenotypic marker for RGCs.12, 20, 52, 59, 60 All RGCs with regenerated neurites were photographed using a fluorescent microscope ( × 200) and neurite length was determined using ImageJ software. In addition, the total number of βIII-tubulin-positive RGCs with an intact nucleus (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI)) per well was quantified to test for potential neurotoxic or neuroprotective effects. At least three independent experiments were performed to verify the results. The average neurite length per RGC was determined by dividing the sum of neurite length per well by the total number of RGCs per well. Values were then normalized to control groups as indicated. The data are the mean±S.E.M. of four replicate wells. The significances of intergroup differences were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, followed by corrections for multiple post hoc tests (Bonferroni-Holm, Tukey).

For immunocytochemical analysis and protein lysate preparation, RGCs were dissociated as described above. Recombinant GST (200 ng/ml), IL-6 (200 ng/ml), IL-6 (200 ng/ml) together with AG490 (20 μM) or hyper-IL-6 (200 ng/ml) was added to the medium of dissociated retinal cultures. After 15 min, cells were fixed and stained with an antibody specific for the phosphorylated form of STAT3 (pSTAT3, 1 : 300; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and an anti-βIII-tubulin-antibody (1 : 2000). To detect mTOR activity, cells were stained with an antibody specific for phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (Cell Signaling, 1 : 300) after 2 hours and 3 days in culture. Each experiment was repeated twice to verify the data. To generate protein lysates, RGCs were harvested after 15 min in culture, centrifuged at 900 r.p.m. for 5 min, and the cell pellets were collected in lysis buffer (see below) and prepared for western blot analysis.

Western blot assays

For retinal lysate preparation, rat retinas were dissected and collected in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS) with protease inhibitors (Calbiochem). Retinas were homogenized by sonification and centrifuged at 5000 r.p.m. for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were analyzed by western blot. Separation of proteins was performed by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, according to standard protocols (Bio-Rad, Hercules, MA, USA). After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The blots were blocked either in 5% dried milk or in 2% ECL Advance blocking agent in Tris-buffered saline-Tween-20. They were then processed for immunostaining with either an antiserum against rat phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705; Cell Signaling; 1 : 5000), a monoclonal antibody against rat β-actin (Sigma; 1 : 7500), or a polyclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor (R&D Systems; 1 : 6000) that was either preadsorbed to a cell-lysate from IL-6 receptor overexpressing HEK 293 cells (pread) or control HEK 293 cells (MOCK) at 4 °C overnight. Bound antibodies were visualized with anti-rabbit, anti-goat or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase diluted to 1 : 80 000 (all Sigma Holland). The antigen–antibody complexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). Western blots were repeated at least twice to confirm results.

Immunohistochemistry

To prepare tissue sections for immunohistochemistry, rats received ONC and after 2 days an intravitreal injection of either BSA (Sigma; 1500 ng) or recombinant IL-6 (1500 ng; Serotec) solution of 5 μl. At least four animals were prepared for each group. Animals were anesthetized and perfused through the heart with cold saline followed by phosphate-buffered saline containing 4% paraformaldehyde 0, 6, 24 and 48 h after the intravitreal injection. Eyes with the optic nerve segments attached were separated from connective tissue, post-fixed for 6 h, transferred to 30% sucrose overnight (4 °C), and embedded in Tissue-Tek (Sakura, Holland). Frozen sections were cut longitudinally on a cryostat, thaw-mounted onto coated glass slides (Superfrost plus, Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and stored at −80 °C until further use. A monoclonal antibody against βIII-tubulin (Babco; 1 : 2000), polyclonal antibody against rat phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705; Cell Signaling; 1 : 300), polyclonal anti-growth-associated protein 43 (anti-GAP-43; custom-made, Invitrogen; 1 : 1000), monoclonal anti-CD 68 (Serotec; 1 : 500), polyclonal anti-IL-6 (R&D Systems, AF506; 1 : 500) and an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody (R&D Systems; 1 : 500) that was either preadsorbed to cell-lysates of IL-6 receptor overexpressing HEK 293 cells (pread) or control HEK 293 cells (MOCK) were used. Secondary antibodies included an anti-mouse IgG, anti-goat IgG, anti-sheep IgG and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen; 1 : 1000). To stain cell nuclei, sections were incubated in a solution containing DAPI for 1 min. Sections were embedded with Mowiol and analyzed using a fluorescent microscope.

Quantification of axons in the optic nerve and of RGCs in retinal cross-sections

Regeneration of axons was quantified as described previously.8, 19, 20 In brief, the number of GAP-43-positive axons extending ≥0.25, ≥0.5 and ≥1 mm from the injury site in rats or ≥0.5, ≥1 and ≥1.5 mm from the injury site in mice in at least six sections per treatment were counted under × 400 magnification, normalized to the cross-sectional width of the optic nerve and used to calculate the total numbers of regenerating axons in each animal. The numbers of βIII-tubulin-positive cells per section were counted in 4–6 retinal sections, averaged per eye and then averaged across all similarly treated animals to obtain the group means and SE as described previously.16, 18, 20 The significances of intergroup differences were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA test, followed by corrections for multiple post hoc tests (Bonferroni–Holm, Tukey). Each experimental group included at least five rats or mice.

Cloning of rat IL-6 and IL-6 receptors

IL-6 cDNA was generated from RNA of peritoneal macrophages, amplified by PCR and cloned into an expression vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) using the following primers: forward: 5′-GCCTACCGCCGATGAAGTTTCTCT-3′ and reverse: 5′-TATAATGCGGCCGCCTAGGTTTGCCGA-3′. Soluble IL-6R (IL-6Rs) was subcloned from the full-length receptor pUC19 plasmid (kindly provided by Professor Scheller) into the pAAV-IRES-hrGFP vector using the following primers: forward: 5′-GCTTAGATTTCGCATGCTGACCGTCG-3′ and reverse: 5′-GCCTACTCGAGCTAGGGCAGGGACATG-3′.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from rat and mouse retinas using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Retina-derived RNA (40 ng) was reverse transcribed using the superscript II kit (Invitrogen). The cDNA quantification of IL-6, Sppr1a, Galanin, Gap43 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression was performed with the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and QuantiTect primers (Mm_Gapdh_3_SG, Mm_Il6_1_SG, Rn_Gapd_1_SG, Rn_Gal_1_SG, Rn_Sprr1a_2_SG, Rn_Gap43_1_SG and Rn_IL-6_1_SG QuantiTect Primer Assay (200); Qiagen) using the Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems 7500). Retina-derived cDNA was amplified during 50 cycles according to the manufacturer's protocol. All reactions were performed in duplicates and at least three independent samples (from different eyes) per group were analyzed. Quantitative analysis was performed using Applied Biosystems 7500 software, calculating the expression of IL-6 relative to the endogenous housekeeping gene GAPDH. Relative quantification was calculated using comparative threshold cycle method (ΔΔCT). Statistical analysis was carried out by ANOVA followed by post hoc test (Bonferroni–Holm, Tukey). The specificity of the PCR products from each run was determined and verified with the dissociation curve analysis feature of the Applied Biosystems 7500 software.

IL-6 ELISA

To determine IL-6 expression in the rat retina 5 days after surgery, retinas were dissected, lysed by sonication in 150 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 250 mM Sucrose, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3Vo4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS) and supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were cleared of debris by centrifugation and protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined by BCA assay (Interchim, France). Fifty microgram of protein were subjected to the ELISA protocol, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Quantikine, R&D Systems). The optical density of each sample was determined in duplicate with a microplate ELISA reader (Tecan, Switzerland). An IL-6 concentration curve was used to determine IL-6 levels in retina lysates. The amount of IL-6 in the entire retina was then extrapolated from the amount of lysate used for ELISA compared with the lysate volume of the total retina. Each group consists of three retinas from three rats, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Rose-John, University of Kiel, Germany for providing hyper-interleukin-6, Professor Scheller, University of Düsseldorf, Germany for IC7, Dr. Sarthy, Northwestern University, Chicago, USA, for the retinal Müller cell line rMC1 and Dr. Thomas Hauk for technical help. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Glossary

- Akt

protein kinase B

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CME

CNS myelin extract

- CNS

central nervous system

- CNTF

ciliary neurotrophic factor

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- GAP-43

growth-associated protein 43

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- gp130

glycoprotein 130

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- IL6−/−

IL-6-deficient mouse

- IL-6Rα

IL-6 receptor-α

- IL6RFL

full length IL-6R

- IL6RS

soluble IL-6R

- IS

inflammatory stimulation

- JAK

janus kinase

- LI

lens injury

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- ONC

optic nerve crush

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase

- RAP

rapamycin

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- rMC1

retinal Müller cell line

- STAT3

signal transducers and activators of transcription-3

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Verkhratsky

Supplementary Material

References

- Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu G, He Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:617–627. doi: 10.1038/nrn1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, Leibinger M. Promoting optic nerve regeneration. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2012;31:688–701. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JL. Intrinsic neuronal regulation of axon and dendrite growth. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Tedeschi A, Park KK, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic mechanisms of axon regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:131–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkelaar M, Clarke DB, Wang YC, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Axotomy results in delayed death and apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells in adult rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4368–4374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, Pavlidis M, Thanos S. Cataractogenic lens injury prevents traumatic ganglion cell death and promotes axonal regeneration both in vivo and in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3943–3954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon S, Yin Y, Nguyen J, Irwin N, Benowitz LI. Lens injury stimulates axon regeneration in the mature rat optic nerve. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4615–4626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04615.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Park KK, Belin S, Wang D, Lu T, Chen G, et al. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature. 2011;480:372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature10594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PD, Sun F, Park KK, Cai B, Wang C, Kuwako K, et al. SOCS3 deletion promotes optic nerve regeneration in vivo. Neuron. 2009;64:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KK, Liu K, Hu Y, Smith PD, Wang C, Cai B, et al. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science. 2008;322:963–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1161566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber B, Berry M, Logan A. Lens injury stimulates adult mouse retinal ganglion cell axon regeneration via both macrophage- and lens-derived factors. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2029–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, Heiduschka P, Thanos S. Lens-injury-stimulated axonal regeneration throughout the optic pathway of adult rats. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:257–272. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernet V, Di Polo A. Synergistic action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and lens injury promotes retinal ganglion cell survival, but leads to optic nerve dystrophy in vivo. Brain. 2006;129 (Pt 4:1014–1026. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, Hauk TG, Muller A, Thanos S. Crystallins of the beta/gamma-superfamily mimic the effects of lens injury and promote axon regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauk TG, Muller A, Lee J, Schwendener R, Fischer D. Neuroprotective and axon growth promoting effects of intraocular inflammation do not depend on oncomodulin or the presence of large numbers of activated macrophages. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:469–482. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Cui Q, Li Y, Irwin N, Fischer D, Harvey AR, et al. Macrophage-derived factors stimulate optic nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2284–2293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02284.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauk TG, Leibinger M, Muller A, Andreadaki N, Knippschild U, Fischer D. Intravitreal application of the Toll-like receptor 2 agonist Pam3Cys stimulates axon regeneration in the mature optic nerve. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;51:459–464. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibinger M, Muller A, Andreadaki A, Hauk TG, Kirsch M, Fischer D. Neuroprotective and axon growth-promoting effects following inflammatory stimulation on mature retinal ganglion cells in mice depend on ciliary neurotrophic factor and leukemia inhibitory factor. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14334–14341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2770-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Hauk TG, Fischer D. Astrocyte-derived CNTF switches mature RGCs to a regenerative state following inflammatory stimulation. Brain. 2007;130 (Pt 12:3308–3320. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D.What are the principal mediators of optic nerve regeneration after inflammatory stimulation in the eye Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010107E8author reply E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z, Berry M, Logan A. ROCK inhibition promotes adult retinal ganglion cell neurite outgrowth only in the presence of growth promoting factors. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;42:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibinger M, Andreadaki A, Fischer D. Role of mTOR in neuroprotection and axon regeneration after inflammatory stimulation. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J. 2003;374 (Pt 1:1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalaris A, Rabe B, Paliga K, Lange H, Laskay T, Fielding CA, et al. Apoptosis is a natural stimulus of IL6R shedding and contributes to the proinflammatory trans-signaling function of neutrophils. Blood. 2007;110:1748–1755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa K, Saito T, Fukunaga T, Sekimori Y, Koishihara Y, Fukui H, et al. Purification and characterization of soluble human IL-6 receptor expressed in CHO cells. J Biochem. 1990;108:673–676. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer J, Effenberger T, Volpi E, Waetzig GH, Bernhardt M, Suthaus J, et al. Constitutively active mutant gp130 receptor protein from inflammatory hepatocellular adenoma is inhibited by an anti-gp130 antibody that specifically neutralizes interleukin 11 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13743–13751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.349167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthaus J, Stuhlmann-Laeisz C, Tompkins VS, Rosean TR, Klapper W, Tosato G, et al. HHV-8-encoded viral IL-6 collaborates with mouse IL-6 in the development of multicentric Castleman disease in mice. Blood. 2012;119:5173–5181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodenkamp J, Waetzig GH, Scheller J, Seegert D, Grotzinger J, Rose-John S, et al. Therapeutic targeting of interleukin-6 trans-signaling does not affect the outcome of experimental tuberculosis. Immunobiology. 2012;217:996–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander U, Pletinckx K, Dohler A, Muller N, Lutz MB, Arzberger T, et al. Neuromelanin is an immune stimulator for dendritic cells in vitro. BMC neuroscience. 2011;12:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbers C, Thaiss W, Jones GW, Waetzig GH, Lorenzen I, Guilhot F, et al. Inhibition of classic signaling is a novel function of soluble glycoprotein 130 (sgp130), which is controlled by the ratio of interleukin 6 and soluble interleukin 6 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42959–42970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Gao Y, Bryson JB, Hou J, Chaudhry N, Siddiq M, et al. The cytokine interleukin-6 is sufficient but not necessary to mimic the peripheral conditioning lesion effect on axonal growth. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5565–5573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0815-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WB, Gardiner NJ, Das P, Qiu J, McMahon SB, Thompson SW. Conditioning injury-induced spinal axon regeneration fails in interleukin-6 knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4432–4443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2245-02.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Wen H, Ou S, Cui J, Fan D. IL-6 promotes regeneration and functional recovery after cortical spinal tract injury by reactivating intrinsic growth program of neurons and enhancing synapse formation. Exp Neurol. 2012;236:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkoum D, Stoppini L, Muller D. Interleukin-6 promotes sprouting and functional recovery in lesioned organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurochem. 2007;100:747–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengottuvel V, Leibinger M, Pfreimer M, Andreadaki A, Fischer D. Taxol facilitates axon regeneration in the mature CNS. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2688–2699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4885-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Hauk TG, Leibinger M, Marienfeld R, Fischer D. Exogenous CNTF stimulates axon regeneration of retinal ganglion cells partially via endogenous CNTF. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;41:233–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavedam UK, Kalies K, Scheller J, Sadeghi H, Gupta Y, Jonkman MF, et al. Recombinant IL-6 treatment protects mice from organ specific autoimmune disease by IL-6 classical signalling-dependent IL-1ra induction. J Autoimmun. 2012;40:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aasland D, Schuster B, Grotzinger J, Rose-John S, Kallen KJ. Analysis of the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor functional domains by chimeric receptors and cytokines. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5244–5252. doi: 10.1021/bi0263311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Goldschmitt J, Peschel C, Brakenhoff JP, Kallen KJ, Wollmer A, et al. I. A bioactive designer cytokine for human hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:142–145. doi: 10.1038/nbt0297-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F, Graeve L. Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J. 1998;334 (Pt 2:297–314. doi: 10.1042/bj3340297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingor P, Tönges L, Pieper N, Bermel C, Barski E, Planchamp V, et al. ROCK inhibition and CNTF interact on intrinsic signalling pathways and differentially regulate survival and regeneration in retinal ganglion cells. Brain. 2008;131 (Pt 1:250–263. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Adel BA, Arnold JM, Phipps J, Doering LC, Ball AK. Ciliary neurotrophic factor protects retinal ganglion cells from axotomy-induced apoptosis via modulation of retinal glia in vivo. J Neurobiol. 2005;63:215–234. doi: 10.1002/neu.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KK, Hu Y, Muhling J, Pollett MA, Dallimore EJ, Turnley AM, et al. Cytokine-induced SOCS expression is inhibited by cAMP analogue: impact on regeneration in injured retina. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;41:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadient RA, Otten UH. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)--a molecule with both beneficial and destructive potentials. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:379–390. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Tanaka K, Suzuki N. Ambivalent aspects of interleukin-6 in cerebral ischemia: inflammatory versus neurotrophic aspects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:464–479. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidlow G, Wood JP, Ebneter A, Casson RJ. Interleukin-6 is an efficacious marker of axonal transport disruption during experimental glaucoma and stimulates neuritogenesis in cultured retinal ganglion cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;48:568–581. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KK, Liu K, Hu Y, Kanter JL, He Z. PTEN/mTOR and axon regeneration. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengottuvel V, Fischer D. Facilitating axon regeneration in the injured CNS by microtubules stabilization. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:391–393. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.4.15552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappington RM, Chan M, Calkins DJ. Interleukin-6 protects retinal ganglion cells from pressure-induced death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2932–2942. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappington RM, Calkins DJ. Pressure-induced regulation of IL-6 in retinal glial cells: involvement of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway and NFkappaB. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3860–3869. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, Petkova V, Thanos S, Benowitz LI. Switching mature retinal ganglion cells to a robust growth state in vivo: gene expression and synergy with RhoA inactivation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8726–8740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2774-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernet V, Joly S, Dalkara D, Jordi N, Schwarz O, Christ F, et al. Long-distance axonal regeneration induced by CNTF gene transfer is impaired by axonal misguidance in the injured adult optic nerve. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;51:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz MP, Horn KP, Tom VJ, Miller JH, Busch SA, Nair D, et al. Chronic enhancement of the intrinsic growth capacity of sensory neurons combined with the degradation of inhibitory proteoglycans allows functional regeneration of sensory axons through the dorsal root entry zone in the mammalian spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8066–8076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2111-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel R, Iannotti CA, Hoh D, Clark M, Silver J, Steinmetz MP. Oncomodulin affords limited regeneration to injured sensory axons in vitro and in vivo. Exp Neurol. 2012;233:708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A, Hauk TG, Leibinger M, Marienfeld R, Fischer D. Exogenous CNTF stimulates axon regeneration of retinal ganglion cells partially via endogenous CNTF. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;41:233–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozdanov V, Muller A, Sengottuvel V, Leibinger M, Fischer D. A method for preparing primary retinal cell cultures for evaluating the neuroprotective and neuritogenic effect of factors on axotomized mature CNS neurons. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2010;Chapter 3:22. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0322s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z, Mazibrada G, Seabright RJ, Dent RG, Berry M, Logan A. TACE-induced cleavage of NgR and p75NTR in dorsal root ganglion cultures disinhibits outgrowth and promotes branching of neurites in the presence of inhibitory CNS myelin. FASEB J. 2006;20:1939–1941. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5339fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier AE, McKerracher L. Expression of specific tubulin isotypes increases during regeneration of injured CNS neurons, but not after the application of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) J Neurosci. 1997;17:4623–4632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, He Z, Benowitz LI. Counteracting the Nogo receptor enhances optic nerve regeneration if retinal ganglion cells are in an active growth state. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1646–1651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5119-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.