Abstract

Purpose

Surgeons serve one of the most challenging and stressful professions. Ineffective control of occupational stress leads to burnout of the surgeon. The aim of this study was to obtain preliminary data on the sources and the degree of stress of surgeons and to determine the feasibility of the survey.

Methods

A total of 63 surgeons in our three affiliated hospitals were enrolled in this study. Fifty-five questions were used to assess the demographics, characteristics and Korean occupational stress scale (KOSS), which were prepared and validated by the National Study for Development and Standardization of Occupational Stress.

Results

Forty-seven of the 63 surgeons participated in this study (74.6%). The mean KOSS score of the survey was 50.9 ± 8.55, which was significantly higher than that of other professions (P < 0.01). Drinking and smoking habits were not related to the KOSS score. Doing exercise was related to a low KOSS score in terms of low KOSS total score (P < 0.01). Average duty hours (P < 0.01) and night duty days per week (P = 0.01) were strongly related to higher KOSS in the linear regression analysis.

Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate job stress of surgeons in Korea. This study showed that Korean Surgeons had higher occupational stress than other Korean professions. A larger study based on this pilot study will help generate objective data for occupational stress of Korean Surgeons by performing a survey of the members of the Korean Surgical Society.

Keywords: Occupational stress, Surgeon, Workload, Korean occupational stress scale (KOSS)

INTRODUCTION

The number of young doctors wanting to be surgeons has continuously decreased in Korea, and the declining rate has been getting progressively worse year by year. In addition, the number of dropouts during surgical training has also increased yearly [1]. There are many factors to consider with regard to this problem; some reasons are unfavorable working conditions and occupational stress of Korean surgeons. The decreasing number of surgeons has caused a vicious circle, leading to a further increase in the existing surgeons' workload and risk of errors.

Occupational stress is considered to result from a combination of high demands with low decision latitude in the workplace [2]. Harmful physical and emotional responses occur when the requirements of a job do not match the capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker. Surgeon is a uniquely specialized occupation with heavy workload that comes with great responsibility with situations involving life and death. Surgeons are expected to cope with unwritten norms such as coming in early and staying late, working nights and weekends, doing high volume of procedures simultaneously, and keeping personal matters aside [3]. This unhealthy overwork has been frequently mistaken as a dedicated duty of a competent surgeon. However, if the stress from this situation is not adequately controlled, it could lead to surgeons' physical and mental distress as well as increased risk of medical errors [4]. Several studies have reported the adverse effect of occupational stress of medical caregivers, including surgeons [4-6]. However, in Korea, no report has been conducted on surgeons' occupational stress or burnout despite tremendous problems regarding surgeons' high workload that have been building up over the years.

Therefore, it is imperative to adequately evaluate the level of occupational stress of Korean surgeons. Previously, a National Study for the Development and Standardization of Occupational Stress was conducted in order to develop and standardize the Korean occupational stress scale (KOSS) [7]. Using this validated scale and large scaled data, we were able to effectively evaluate the KOSS and stress factors related to surgeons and compared the results with other specialized professions which were previously evaluated in a large number of Korean workers.

Before conducting the survey, we investigated 63 surgeons in our three affiliated hospitals as a pilot study. The aim of this study was to obtain preliminary data on the sources and the degree of stress of surgeons and to evaluate the feasibility of the survey.

METHODS

Participants

The population consisted of general clinicians in the department of surgery at three university affiliated hospitals. More specifically, the participants included professors (n = 25), fellows (n = 21) and surgical residents (n = 17). We obtained all their e-mail addresses which were permitted to be used for correspondence. Participation was elective and all responses were anonymous.

Data collection

Surgeons were surveyed by e-mail during the period of 10 days in April 2012. The cover letter stated the purpose of the survey which is better understanding the factors that contribute to occupational stress among surgeons. By following the link in the e-mail, participants were able to access the survey website.

Fifty-five questions were used to assess the demographics, characteristics and KOSS, which were prepared and validated by the National Study for Development and Standardization of Occupational Stress. A full version of the KOSS was used to measure occupational stress [7]. It consisted of the following eight subscales using factor analysis and validation process: physical environment (3 items), job demand (8 items), insufficient job control (5 items), interpersonal conflict (4 items), job insecurity (6 items), organizational system (7 items), lack of reward (6 items), and occupational climate (4 items) (Suppl. 1). The survey included 43 validated questions on a 4 point Likert scale [7] and 11 independent variable questions. The independent variable questions were made up of individual characteristics: gender, position, subspecialty, average duty hours per week, average night duty days per week, and personal habits. At the end of the survey, participants could check their own stress score and then compare their score with the average scores of other specialized jobs.

Statistical analysis

The occupational stress scale was measured by KOSS. Internal consistency was also calculated as Cronbach's alpha. The KOSS score are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The baseline demographic and health behavior variables were compared using Student's t-test or one-way variance of analysis for KOSS score. To evaluate the relation between night duty-day or duty hours and KOSS score, simple linear regression was performed.

To compare surgeon's stress scale with other scales of specialized jobs, we performed one sample t-test based on the researched report by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (2005) [8,9]. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and a P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

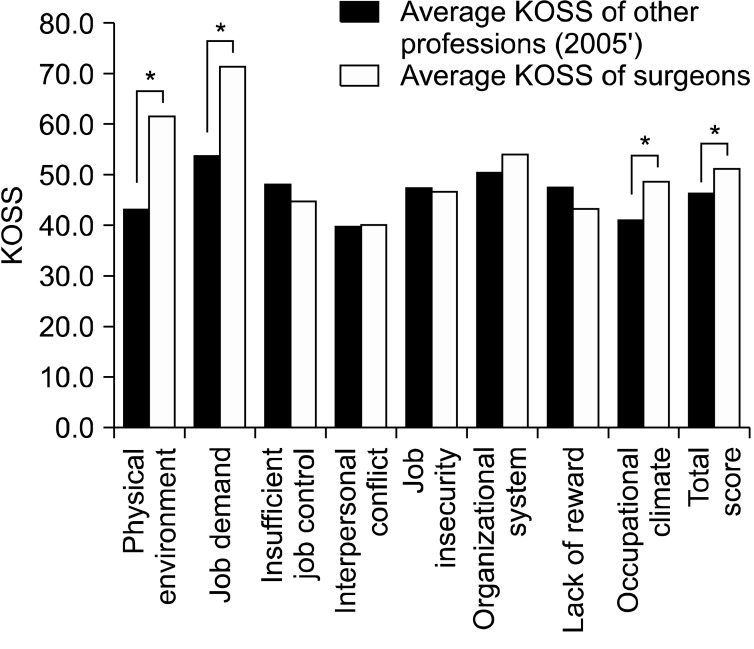

Among 63 surgeons who received the survey mail, 47 participants completed the questionnaire. The response rate was 74.6% (47/63). The mean overall KOSS of the participants was 50.9 ± 8.55, which is significantly higher than other professions (P<0.01). Among the eight subscale of occupational stress, surgeons showed higher scale than other specialized jobs in terms of physical environment, job demand, organizational system, and occupational climate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison Korean occupational stress scale (KOSS) of surgeons with other professions: one asterisk indicates statistical significance (*P<0.05).

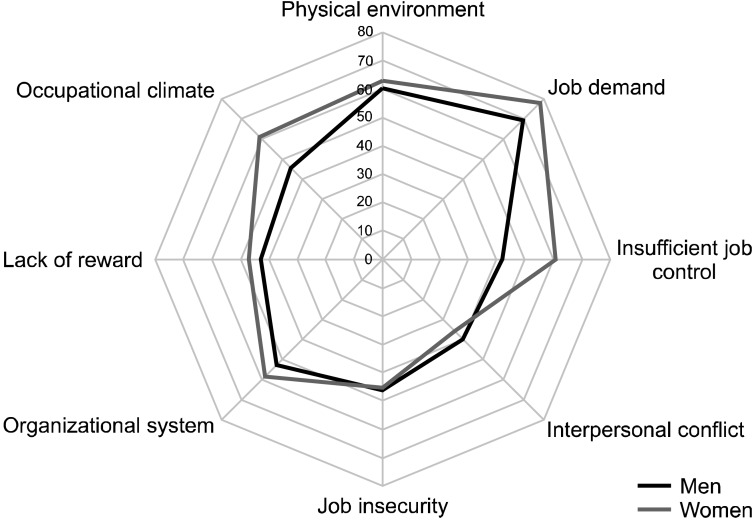

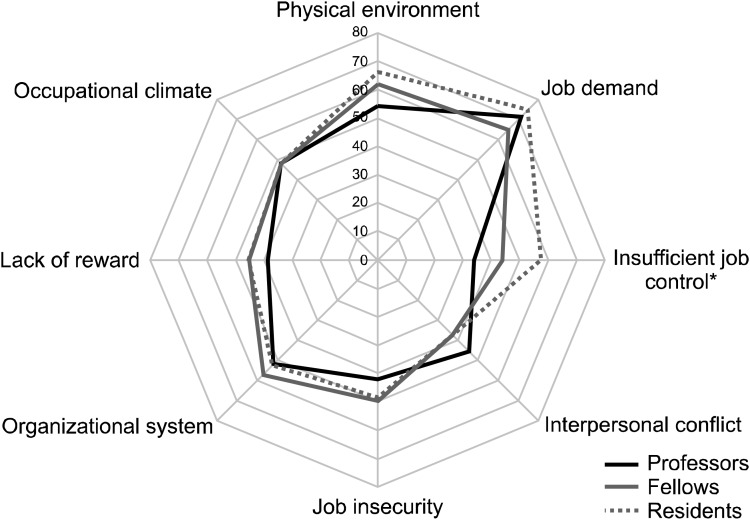

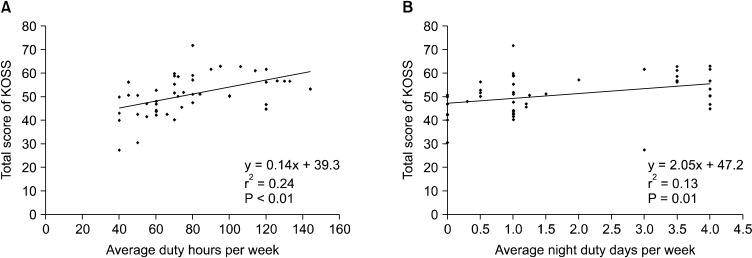

Characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. Women seemed to have higher KOSS in general, but it did not show statistical significance (Fig. 2). With respect to career characteristics, residents showed higher overall KOSS, though not statistically significant. In detail, fellows than professors, residents than fellows had more stress about insufficient job control (P<0.01) (Fig. 3). There was no difference in the analysis of KOSS by subspecialty.

Table 1.

Personal characteristics

KOSS, Korean occupational stress scale; SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Relation of Korean occupational stress scale with gender.

Fig. 3.

Relation of Korean occupational stress scale with position: one asterisk indicates statistical significance (*P<0.05).

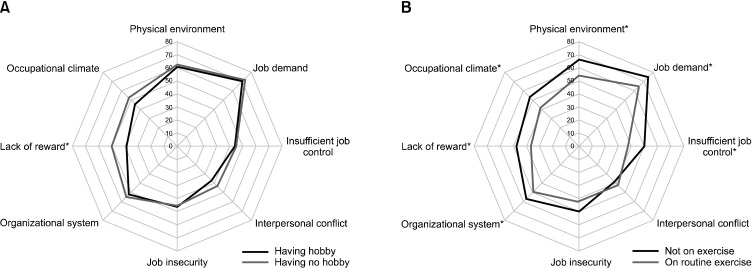

Drinking and smoking habits were not significantly related to occupational stress. However, surgeons with a hobby showed lower KOSS especially in lack of reward than those who did not have a hobby (P<0.01). Furthermore, doing exercise showed a strong relation to KOSS subscales, most subscales were lower in the group who didn't regular exercise, except for two subscales; job insecurity and interpersonal conflict (Fig. 4) (physical environment, P<0.01; job demand, P = 0.02; insufficient job control, P<0.01; organized system, P = 0.02; lack of reward, P<0.01; occupational climate, P = 0.04).

Fig. 4.

Relation of Korean occupational stress scale with hobby (A) and exercise (B): one asterisk indicates statistical significance (*P<0.05).

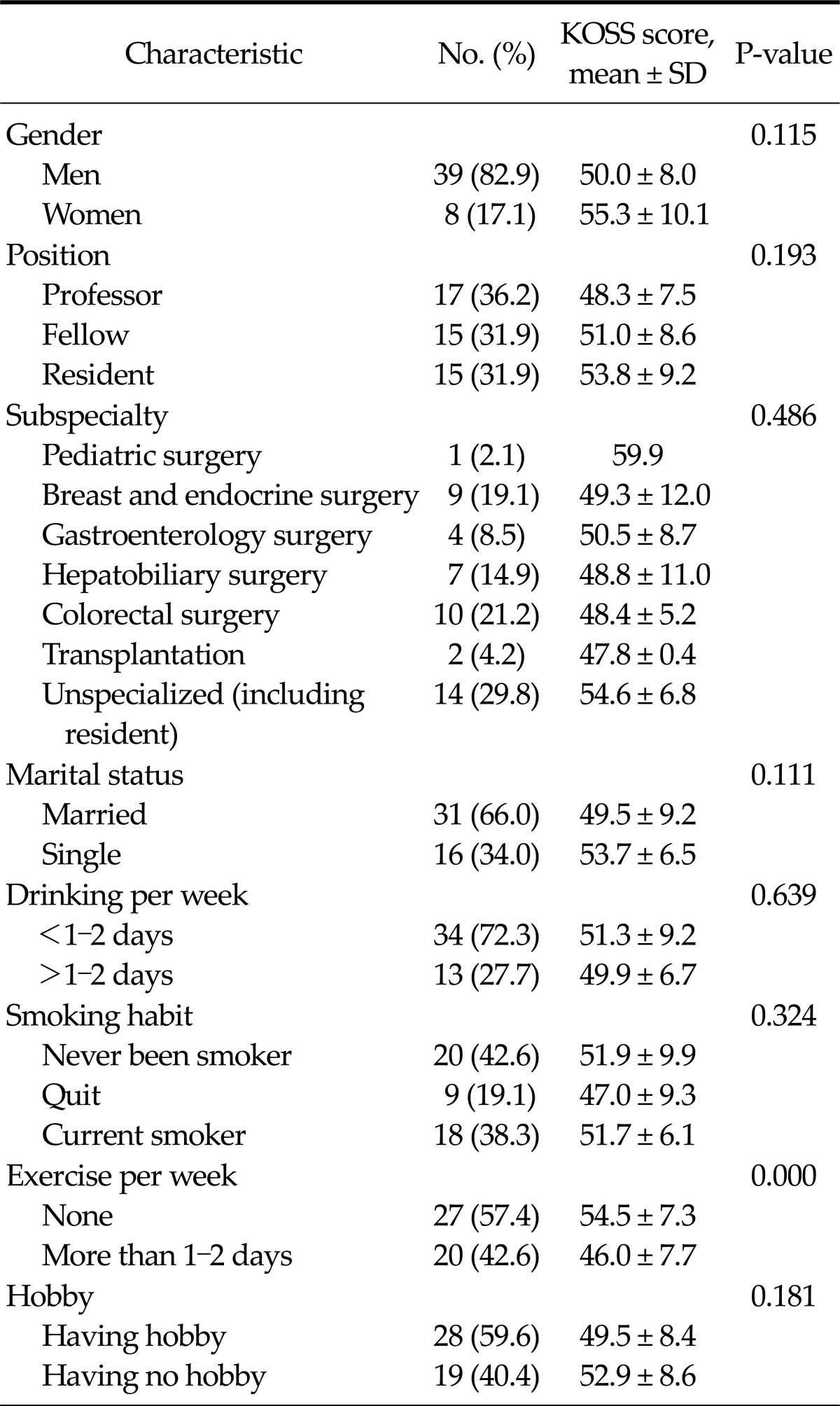

Average duty hours (P<0.01) and night duty days per week (P<0.01) were strongly related to higher KOSS in the linear regression analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Linear regression analysis of average duty hours (A) and duty days (B) per week. KOSS, Korean occupational stress scale.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first report to analyze occupational stress of Korean surgeons. The aim of the study was to obtain preliminary data on the sources and the degree of stress of surgeons and to determine the feasibility of the survey before conducting a larger study. We used validated questions developed by the National Study for Development and Standardization of Occupational Stress (NSDSOS Project: 2002-2004) [8]. The questionnaire is called the KOSS which is considered to be unique and validated barometer for stress in Korean employees [7]. In addition, we added some questions that were related to professional characteristics and personal life style.

The mean KOSS score was significantly higher that of other specialized jobs. Among the eight subscales of occupational stress, surgeons showed a higher scale in physical environment, job demand, organizational system, and occupational climate. This means that surgeons have relatively more stress due to difficult physical environment, higher job demand, organizational injustice and discomfort in their occupational climate. This result is not surprising considering the fact that surgeons usually work in the operating room and the emergency department for a long time where they frequently face challenges of life or death situations. Organization injustice and discomfort in the occupational climate may be caused by the deep-rooted unfavorable medical circumstances for Korean surgeons such as the apprentice like training system and unfair treatment from their hospital due to low medical insurance fee. Discomfort in the occupational climate seems to be a particular stress factor that is generally present in Korean occupational culture, which is caused by the hierarchical and authoritarian system, collectivism, and gender discrimination. We should keep an eye on this finding and try to control this factor because discomfort in the occupational climate was found to be a powerful predictor of depression in Korean employees [9]. Based on the analysis according to the job position, residents had more stress regarding insufficient job control than professors and fellows. That is probably due to shortage of surgical residents, work overload and authoritarian atmosphere of the apprentice like training system of Korea.

Stress is a reaction to the demands being made on an individual. Occupational stress is comprised of complex conditions and is described as the sum of physical, mental and psychological responses to work that are transformed into emotional reactions [10]. Therefore, the individual's ability to cope with such demands is also important factors in the experience of occupational stress. Surgeons usually do not have much time to manage their stress due to their high workload, therefore, as a way of using spare time and dealing with stress, drinking and smoking are regarded as common habits of Korean surgeons. However, drinking and smoking habits were not related to low score in the KOSS. This intriguing result suggests that drinking and smoking could not be an effective strategy for controlling stress. As a self-care strategy to deal with occupational stress, having a hobby and doing exercise seem to be effective. Having a hobby and doing regular exercise were significantly related to the low KOSS in our study. Many previous reports also suggest the positive effect of exercise and using personal wellness promotion strategies [11-13]. On the basis of this preliminary result, we are planning to investigate on strategies to control one's own physical, mental, psychological wellness and analyze the relation to the level of surgeon's stress in a future study.

Our result also showed that increasing hours and increasing night on call duty are associated with higher KOSS score. This is consistent with other previous reports [14]. There is no clear cut of hours or night duty to prevent increasing distress, but surgeons who worked on call 2 nights or more per week, and those who worked 80 hours or more per week showed a greater incidence of distress in a previous study [3,15]. We should focus on these factors in a further study involving a larger population to adequately analyze the relationship between the level of stress and working hours of surgeons.

This pilot study has limitations such as the small sample size and selection bias. These preliminary results may not be conclusive but can give us many meaningful clues evidenced by internal consistency. Consistent with our expectation, surgeons have higher occupational stress than other professions. Long working hours, night duty, and individual strategy in dealing with stress were found as factors related to a higher stress scale. The next phase of this study is to expand the results to the member of the Korean Surgical Society and generate a much greater number of responses. A larger number of participants would allow us to evaluate the KOSS score and potential factors of stress more objectively.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Korean Surgical Society.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material can be found via http://thesurgery.or.kr/src/sm/jkss-84-261-s001.pdf.

References

- 1.Kim SK. How to save surgical residents in crisis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2009;76:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal T, Alter A. Occupational stress and hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Freischlag JA, Shanafelt TD. Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg. 2009;144:371–376. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302:1294–1300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West CP, Drefahl MM, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Internal medicine resident self-report of factors associated with career decisions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:946–949. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1039-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang SJ, Koh SB, Kang D, Kim SA, Kang MG, Lee CG, et al. Developing an occupational stress scale for Korean employees. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2005;17:297–317. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho JJ. Study for evaluation of validity and relability to Korean occupational stress scale. Incheon: Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute, Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho JJ, Kim JY, Chang SJ, Fiedler N, Koh SB, Crabtree BF, et al. Occupational stress and depression in Korean employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;82:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaPorta LD. Occupational stress in oral and maxillofacial surgeons: tendencies, traits, and triggers. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2010;22:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Hanks JB, Sloan JA, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255:625–633. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b2fa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swetz KM, Harrington SE, Matsuyama RK, Shanafelt TD, Lyckholm LJ. Strategies for avoiding burnout in hospice and palliative medicine: peer advice for physicians on achieving longevity and fulfillment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:773–777. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner EL, Swain GR, Wolf B, Gottlieb M. A qualitative study of physicians' own wellness-promotion practices. West J Med. 2001;174:19–23. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, Sloan JA, Russell TR, Bechamps GJ, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among surgeons: whether specialty makes a difference. Arch Surg. 2011;146:385–386. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material can be found via http://thesurgery.or.kr/src/sm/jkss-84-261-s001.pdf.