Abstract

The success of any biobank depends on a number of factors including public's view of research and the extent to which it is willing to participate in research. As a prototype of surrounding countries, public interest in research and biobanking in addition to the influence and type of informed consent for biobanking were investigated in Jordan. Data were collected as part of a national survey of 3196 individuals representing the Jordanian population. The majority of respondents (88.6%) had a positive perception of the level of research in Jordan and they overwhelmingly (98.2%) agreed to the concept of investing as a country in research. When respondents were asked if the presence of an informed consent would influence their decision to participate in biobanking, more individuals (19.8%) considered having an informed consent mechanism as a positive factor than those who considered it to have negative connotations (13.1%). However, a substantial portion (65%) did not feel it affected their decision. The majority of survey participants (64%) expressed willingness to participate in biobanking and over 90% of them preferred an opt-in consent form whether general (75.2%) or specific for disease or treatment (16.9%). These results indicate a promising ground for research and biobanking in Jordan. Educational programs or mass awareness campaigns to promote participation in biobanking and increase awareness about informed consent and individual rights in research will benefit both the scientific community as well as the public.

Keywords: biobanking, informed consent, public opinion, Jordan, Middle East, research participation

Introduction

The existence of an informed consent process is integral in assuring the ethical conduct of biomedical research involving human subjects as declared by the Nuremeberg Code in 1947 and affirmed 16 years later by the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. The US National Bioethics Advisory Commission subsequently considered informed consent a means by which researchers show respect for research participants, and is a basis for protecting the privacy of individuals and safeguarding their information.1 Recently, many countries are showing increasing interest in development of national biobanks. This interest brings with it the promise of promoting research and, ultimately, better healthcare. The latter service would accommodate the unique genetic and ethnic diversity of the population covered by such facilities. Jordan, in the Middle East, is also considering the establishment of its own biobanking facilities. Expectedly, the success of such projects will be linked to the magnitude of public perception of and level of participation in research and biobanking. In fact, evaluating public support for research and biobanking and preference with regards to consent, as well as understanding cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds that can influence such perceptions, are important in preparing for the establishment of biobanking facilities.2 Such information would help in designing a realistic set of laws that can promote and organize biomedical research while protecting individuals.

This article presents part of the results of a national study within which a specific section on biobanking was included. An assessment of public views of biomedical research and biobanking as well as the influence and type of informed consent was carried out. As a prototype of other Middle Eastern countries, the study provides an opportunity for means of accessing the public in the region.

Methods

Questions related to biomedical research, biobanking, and informed consent were part of a nationwide, structured, cross-sectional survey in Jordan to measure knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards cancer prevention and care.3, 4 The survey sample was designed according to Department of Statistics guidelines using the 2004 Population and Housing Census to ensure that the final sample reflected the socioeconomic and demographic distribution of Jordan (see Supplementary Table S1 of the supplementary data). The survey included 3196 individuals aged 18 years and above during the period of January–March 2011. Trained individuals went to assigned houses, and interviewed all participants.

Five major questions were utilized to measure perceptions regarding biobanking and research. First, participants were asked of their level of agreement with two statements: ‘Jordan is advanced in scientific research' and ‘it is important to invest in promoting scientific research in Jordan' (a four-point Likert scale of agreement was used). A paragraph introducing the biobanking project was read to survey participants. The importance of informed consent was then assessed by asking participants how ‘their decision to donate biological sample(s) and information (for biobanking) would be influenced if they knew a signed consent form would be obtained before donation' (four choices were used–positively, negatively, no effect, and do not know). Likelihood of donating a biological sample was evaluated based on a four-point Likert scale of likelihood. Finally, respondents likely to participate in biobanking were provided with four types of consent form they would prefer if they decided to donate a biological sample. The four options of consent were: open for all research studies, disease- or treatment-specific research, specific for a research project with the possibility of renewal, and specific for a research project without the possibility of renewal.

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software program. Descriptive statistics were used to report sample characteristics in addition to frequencies and percentages. Pearson correlation coefficient and Pearson Chi-square were used to assess the relationship of demographics (age, gender, and educational level) with the attitudinal statements. Detailed data and statistical analyses are provided in the supplementary file.

Results

A considerable majority (90%) agreed that Jordan is advanced in scientific research (Q1, Table 1; Supplementary Table S2). There was a significant correlation between agreement with the latter statement with being female (r=−0.083, P<0.001) and lower educational status (r=0.115, P<0.001). Furthermore, there was an overwhelming agreement (98.2%) to the statement ‘it is important to invest in promoting scientific research in Jordan' (Q2, Table 1; Supplementary Table S3). A significant association between this perception and higher educational status was revealed (r=0.088, P<0.001).

Table 1. Summary of participants' responses (N=3196).

| Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: Jordan is advanced in scientific research | 1170 (36.6) | 1662 (52.0) | 277 (8.7) | 87 (2.7) | |

| Q2: What do you think about the following statement: ‘it is important to invest in promoting scientific research in Jordan?' | 1571 (49.2) | 1566 (49.0) | 53 (1.6) | 6 (0.2) | |

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | No Effect (%) | Don't know (%) | ||

| Q3: Will your decision to donate biological sample(s) and information (for biobanking) be influenced if you know that: A signed consent of donors will be obtained before donation? | 633 (19.8) | 417 (13.1) | 2078 (65.0) | 68 (2.1) | |

| Very likely (%) | Likely (%) | Unlikely (%) | Very Unlikely (%) | Don't know (%) | |

| Q4: How likely are you to donate biological (blood, urine, or tissue samples) for the (biobanking) project? | 446 (14.0) | 1594 (49.9) | 716 (22.4) | 430 (13.4) | 11 (0.3) |

After introducing the biobanking initiative, survey participants were asked whether or not their decision to donate biological samples and information (for biobanking) would be influenced if a signed consent was to be obtained before donation. The majority (65%) thought that the elicitation of consent before donation would not have any influence on their decision (Q3, Table 1; Supplementary Table S4). Approximately 20% identified obtaining a consent would have a positive influence on their decision to donate, whereas 13.1% rated it as a having a negative connotation. Statistical significance was found between negative perception of consent and being 60 years or older (χ2=14.589, P=0.006). Statistical significance was also associated between those who had lower educational level (χ2=27.53, P<0.001) and were 60 years or older (χ2=38.01, P<0.001) with the group that answered ‘do not know', although the latter was small (2.1%).

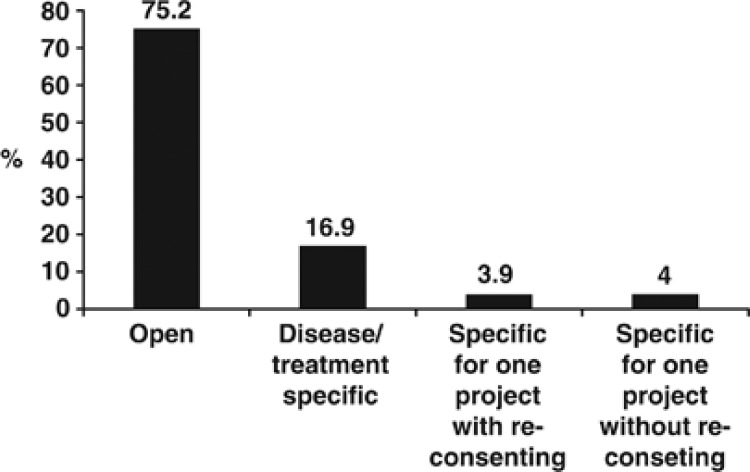

Participants were asked about their willingness to donate biospecimen to a future biobank (Q4, Table 1; Supplementary Table S5). Approximately two-third of respondents (64%) were ‘very likely' or ‘likely' to donate a specimen. Likelihood of donation was associated with a higher level of education (r=0.097, P<0.001), and younger age (r=−0.126, P<0.001). Those who expressed willingness to contribute biospecimens for biobanking (N=2051) were then asked about their preferred type of informed consent. Seventy-five percent of participants preferred a general, open-ended consent (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S6), and this selection was significantly associated with being male (χ2=10.344, P=0.001) and older in age (χ2=13.466, P=0.009). Disease- or treatment-specific consent was chosen by 16% of the respondents. Preference of this consent was associated with being female (χ2=9.116, P=0.003) and younger (χ2=13.871, P=0.008). Finally, approximately 8% of respondents equally chose consent for one research project (with or without renewal).

Figure 1.

The preferred type of a consent form among individuals willing to participate in biobanking (N=2051).

Discussion

The study provides multiple positive indications for establishing a strong infrastructure for biomedical research in Jordan. Our results, which represent the Jordanian population, show that Jordanians have a positive view of research. Specifically, Jordanians had a positive perception of the level of scientific research in Jordan, expressed strong support for investing in research promotion, were likely to participate in biobanking, and preferred opt-in consent. However, it is important to note that one-third of Jordanians were not willing to participate in biobanking. We expect that this low rate for participation in biobanking can be improved with organized awareness programs. This statement is corroborated by the correlation between increasing educational level of respondents with willingness to participate in biobanking as well as enthusiasm to invest in research. Though, further studies on specific subgroups will be of interest to evaluate the effect of specific situations or environments on the support of research (eg, individuals suffering from specific medical conditions or those visiting a health facility). Interestingly, a small-scale survey conducted among visitors of a cancer center in Jordan revealed a higher rate of willingness to participate in biobanking than illustrated herein among the general population (M Al-Hussaini, personal communication).

With regards to informed consent, the majority of those expressed willingness to participate in biobanking preferred an open consent format. Preference of a general informed consent in Jordan is comparable to what was reported in Sweden5 where 70% of those surveyed were willing to provide a general consent, and higher than rates reported in Ireland and Finland (44% and 34%, respectively).6, 7 However, the majority of Jordanians did not seem to be concerned about the existence of an informed consent. This result is not consistent with other international studies. For example, in a Japanese study, while respondents were supportive of research, there was concern about the use of samples without consent.8 Additionally, participants of an Egyptian, interview-based study expressed high value of having an informed consent.9

There has been much debate with regards to what type of informed consent is needed for an effective biobank. Whereas Hansson et al10 have been proponents of a broad consent governed by research ethics guidelines and personal choices, others have argued against such a consent method on the basis of ethical challenges that can threaten trust in biomedical research.11, 12, 13 A number of attempts have been presented for an ethical and simple informed consent for biobanking purposes taking into consideration national and international regulations.14, 15, 16 Overall, the informed consent must ensure participants' integrity, privacy, and safety. Moreover, it must align with both national and international regulations to permit cross-border collaborations. Yet, we believe the research consent must be open enough to promote diverse research activities.

Trust is an integral part in successful operation of biobanks.17, 18, 19, 20 In fact, numerous studies have found a positive correlation between level of trust and degree of participation not only in biobanking, but in research as a whole.5, 6, 8, 9, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Although further work would be needed to explicitly measure trust in research enterprises and researchers, our results may be indicative of trust of respondents in the scientific community in Jordan. Public engagement, dialogues, and communication have been suggested as means of establishing public trust among participants.20, 26 Such strategies will have an important role in bridging the scientific community in Jordan to the public. We also suggest that the credibility of any biobanking initiative in Jordan may be further enforced by promoting on-going, consistent, and successful biomedical research that can showcase the value of public donations in furthering research for the benefit of the Jordanian society.

A number of limitations exist in this study. It is important to take into account that intention to participate in biobanking and provide a certain type of consent form may not reflect actual behavior. In addition, consistent with other self-report interview method, individuals may be reluctant to explicitly state their views objectively and would rather provide biased answers that are socially acceptable. Nevertheless, our study is important because it evaluated the attitudes of a nationally representative sample of Jordanians who were interviewed in their homes. This is in contrast to studies conducted on individuals visiting health facilities, where they might provide more biased answers. On a country level, our results also offer valuable information with regards to the potential viability of biobanks and research initiatives in Jordan and, possibly, surrounding countries. We stress on the need to initiate public awareness and educational programs to encourage participation in research and inform participants of their rights and responsibilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD). The KAP Survey was implemented by King Hussein Institute for Biotechnology and Cancer (KHIBC) under The National Life Science Research and Biotechnology Promotion (LSR/BTP) Initiative in Jordan. We would thank Dr Nour Obeidat for her critical reading of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- National bioethics advisory commission Research involving human biological materials: ethical issues and policy guidance 1999. Vol I, http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/pcbe/reports/past_commissions/nbac_biological1.pdf (Accessed 1 April 2012).

- Hoeyer K. Donors perceptions of consent to and feedback from biobank research: time to acknowledge diversity. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:345–352. doi: 10.1159/000262329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Al Gamal E, Othman A, Nasrallah E. Report. Amman, Jordan: King Hussein Institute for Biotechnology and Cancer (KHIBC); 2011. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards cancer prevention and care in Jordan. [Google Scholar]

- Ahram M, Othman A, Shahrouri M. Public Perception towards Biobanking in Jordan. Biopreserv Biobank. 2007;10:361–365. doi: 10.1089/bio.2012.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettis-Lindblad A, Ring L, Viberth E, Hansson MG. Perceptions of potential donors in the Swedish public towards information and consent procedures in relation to use of human tissue samples in biobanks: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:148–156. doi: 10.1080/14034940600868572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins G, McGee H, Ring L, et al. Public perceptions of biomedical research: a survey of the general population in Ireland Health Research Board;2005: Dublin; http://epubs.rcsi.ie/psycholrep/8/ (Accessed 1 April 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Tupasela A, Sihvo S, Snell K, Jallinoja P, Aro AR, Hemminki E. Attitudes towards biomedical use of tissue sample collections, consent, and biobanks among Finns. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:46–52. doi: 10.1177/1403494809353824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai A, Ohnishi M, Nishigaki E, Sekimoto M, Fukuhara S, Fukui T. Attitudes of the Japanese public and doctors towards use of archived information and samples without informed consent: preliminary findings based on focus group interviews. BMC Med Ethics. 2002;3:E1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil SS, Silverman HJ, Raafat M, El-Kamary S, El-Setouhy M. Attitudes, understanding, and concerns regarding medical research amongst Egyptians: a qualitative pilot study. BMC Med Ethics. 2007;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson MG, Dillner J, Bartram CR, Carlson JA, Helgesson G. Should donors be allowed to give broad consent to future biobank research. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:266–269. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann B. Broadening consent--and diluting ethics. J Med Ethics. 2009;35:125–129. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.024851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschke KJ. Alternative consent approaches for biobank research. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:193–194. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdows H, Cordell S. The ethics of biobanking: key issues and controversies. Health Care Anal. 2011;19:207–219. doi: 10.1007/s10728-011-0184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM, Friedman JY, Hardy NC, Lin L, Weinfurt KP. Developing a simplified consent form for biobanking. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha AC, Seoane JA. Alternative consent models for biobanks: the new Spanish law on biomedical research. Bioethics. 2008;22:440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteri C, Borry P. A proposal for a model of informed consent for the collection, storage and use of biological materials for research purposes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson MG. Ethics and biobanks. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:8–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson MG. Building on relationships of trust in biobank research. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:415–418. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.009456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke AA, Wolf WA, Hebert-Beirne J, Smith ME. Public and biobank participant attitudes toward genetic research participation and data sharing. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:368–377. doi: 10.1159/000276767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambon-Thomsen A, Rial-Sebbag E, Knoppers BM. Trends in ethical and legal frameworks for the use of human biobanks. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:373–382. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00165006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettis-Lindblad A, Ring L, Viberth E, Hansson MG. Perceptions of potential donors in the Swedish public towards information and consent procedures in relation to use of human tissue samples in biobanks: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:148–156. doi: 10.1080/14034940600868572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM, Dean E. Informed consent for biorepositories: assessing prospective participants' understanding and opinions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1440–1451. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley CR, Nicol D, Otlowski MF, Stranger MJ. Predicting intention to biobank: a national survey. Eur J Public Health. 2010;22:139–144. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauth JM, Musa D, Siminoff L, Jewell IK, Ricci E. Public attitudes regarding willingness to participate in medical research studies. J Health Soc Policy. 2000;12:23–43. doi: 10.1300/J045v12n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Chang C, et al. For what am I participating? The need for communication after receiving consent from biobanking project participants: experience in Japan. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:358–363. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.