Abstract

The therapeutic activity of selective serotonin (5-HT) reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) relies on long-term adaptation at pre- and post-synaptic levels. The sustained administration of SSRIs increases the serotonergic neurotransmission in response to a functional desensitization of the inhibitory 5-HT1A autoreceptor in the dorsal raphe. At nerve terminal such as the hippocampus, the enhancement of 5-HT availability increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) synthesis and signaling, a major event in the stimulation of adult neurogenesis. In physiological conditions, BDNF would be expressed at functionally relevant levels in neurons. However, the recent observation that SSRIs upregulate BDNF mRNA in primary cultures of astrocytes strongly suggest that the therapeutic activity of antidepressant drugs might result from an increase in BDNF synthesis in this cell type. In this study, by overexpressing BDNF in astrocytes, we balanced the ratio between astrocytic and neuronal BDNF raising the possibility that such manipulation could positively reverberate on anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activities in transfected mice. Our results indicate that BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes produced anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activity in the novelty suppressed feeding in relation with the stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis whereas it did not potentiate the effects of the SSRI fluoxetine on these parameters. Moreover, overexpressing BDNF revealed the anxiolytic-like activity of fluoxetine in the elevated plus maze while attenuating 5-HT neurotransmission in response to a blunted downregulation of the 5-HT1A autoreceptor. These results emphasize an original role of hippocampal astrocytes in the synthesis of BDNF, which can act through neurogenesis-dependent and -independent mechanisms to regulate different facets of anxiolytic-like responses.

Keywords: antidepressant, astrocytes, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, hippocampus, neurogenesis, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Introduction

The therapeutic activity of selective serotonin (5-HT) reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) relies on long-term adaptation at pre- and post-synaptic levels. At the post-synaptic level, compelling evidence has demonstrated that the sustained, but not acute, administration of SSRIs stimulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis, whereas the disruption of this phenomenon prevents the behavioral effects of these antidepressants in mice.1 Although the complex biological and psychobiological changes associated with depression and related treatments cannot be attributed to neurogenesis alone,2 this particular property of SSRIs has been reported in humans3 and in non-human primates.4 We recently demonstrated that the disruption of adult hippocampal neurogenesis compromises the anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activity of the SSRI fluoxetine in some, but not all, behavioral paradigms, thereby suggesting the existence of both neurogenesis-dependent and neurogenesis-independent mechanisms of action.5 A number of factors have been proposed to participate in SSRI-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Among the many long-term targets of SSRI treatments, neurotrophins, particularly brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), have been well studied. BDNF is the most abundant neurotrophin in the brain and is predominantly synthesized by neurons, where the normal physiological levels are rapidly and potently regulated through ongoing neuronal activity.6 Evidence demonstrates that chronic SSRI treatments increase BDNF expression in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus,7 which in turn promotes the in vivo proliferation and differentiation of neuronal progenitor cells,8, 9, 10, 11 accelerates the maturation of newborn neurons and facilitates their survival.10, 11, 12 Taken together, these data establish a relationship between antidepressant activity, BDNF synthesis and the stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis.

There is increasing evidence that SSRIs also activate glial cells, particularly astrocytes.13 Consistent with this hypothesis, fluoxetine has been shown to reverse the stress-induced reduction of hippocampal glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression in rats.14 Therefore, an increased activity or density of astrocytes could represent a common cellular mechanism underlying the effects of pharmacological15 and non-pharmacological antidepressive strategies.16 In vitro studies suggest that astrocytes express very low levels of BDNF,17 and whether this neurotrophin would be recruited in response to antidepressant treatment to modulate their therapeutic activity remains unknown. The presence of SERT (serotonin transporter) on astrocytes18, 19 along with the recent observation that fluoxetine upregulates BDNF in primary astrocyte cultures20 support this hypothesis but has never been examined in vivo.

In the present study by selectively overexpressing BDNF in hippocampal astrocytes by the mean of an original and efficient gene transfer strategy,21 we balanced the ratio between neuronal vs astrocytic BDNF thereby modeling the putative post-synaptic activity of SSRIs. We anticipated that such manipulation either alone or in combination with the sustained administration of fluoxetine could positively reverberate on the anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like behavior of transfected mice. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that changes in behavioral responses might result from the finely tuned regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis and/or serotonergic neurotransmission, which are two major elements in the therapeutic activity of SSRIs. Depending on the paradigm, the overexpression of BDNF in hippocampal astrocytes elicited anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effects either alone or in combination with fluoxetine thereby providing the first in vivo evidence that this cell type might be a key partner of neurons during antidepressant treatment.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male SvEv129 mice (7- to 9-week-old), weighing 25–35 g (Taconic, Ejby, Denmark) were used in the present study according to the protocol described in Supplementary Figure S1. They were initially divided into two groups pre-injected with lentiviral vector containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) (lenti-GFP control mice) or the BDNF (lenti-BDNF mice). One month after stereotaxic injection of lentivirus, lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice were administered the vehicle or fluoxetine for 4 weeks.

Stereotaxic injection of lentiviral vector

For the stereotaxic injections, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (75 mg kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1), administered intraperitoneally (i.p.). Lentiviral vectors (see Supplementary Materials and Methods) were injected using 34-gauge blunt-tip needle linked to a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) by a polyethylene catheter. The viruses were diluted in PBS-1% BSA to reach a final concentration of 100 ng p24 μl−1. Mice received a total volume of 1 μl at a rate of 0.2 μl min−1. The stereotaxic coordinates for the bilateral injections in the hippocampus were (in mm from bregma): anteroposterior (AP) −2.2, lateral (L) ±2.0 and ventral (V) −2.0 (according to Paxinos and Franklin22). At the end of the injection, the needle was left in place for 5 min before being slowly removed. The labeling of the site of injection by GFP is depicted in Figure 1e and Supplementary Figure S2A.

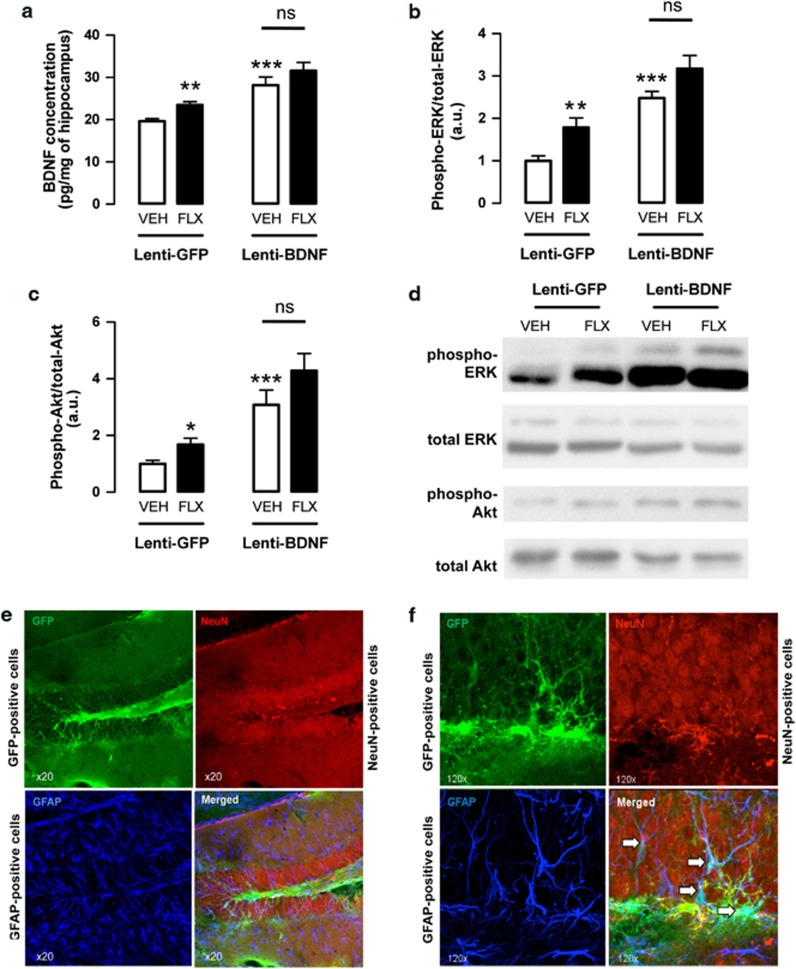

Figure 1.

In vivo validaton of lentiviral vector on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) overexpression/signaling and cellular tropism in the adult mouse hippocampus. Mice were microinjected with either lentiviral vector-expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) alone (Lenti-GFP) or lentiviral vector-expressing the human BDNF gene (Lenti-BDNF) within the hippocampus. (a) In vivo measurements of BDNF concentration in the hippocampus of adult Lenti-GFP or Lenti-BDNF mice administered either with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or with fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks. Values are mean±s.e.m. of BDNF concentration (pg mg−1) (n=3–8 per group). (b, c) Phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and protein kinase B (Akt) in the hippocampus of adult mice microinjected with Lenti-GFP or Lenti-BDNF administered either with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or with fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks. Values are mean±s.e.m. of phospho-ERK or phospho Akt/total ERK or total Akt (arbitrary unitary, a.u.) (n=3–8 per group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-GFP mice administered with vehicle for 4 weeks. NS, not significant. (d) Western blot showing the phosphorylation of ERK and Akt in each experimental group. (e, f) Confocal micrographs ( × 20 and × 120) of a representative transduced dentate gyrus (DG) showing the immunostaining for GFP- (green; up left panel), GFAP- (dark blue; down left panel) and NeuN-positive cells (red, up right panel). Merged is depicted on the down right panel. The white arrows indicate transduced astrocytes.

ELISA and western blots

BDNF levels in the hippocampus and the striatum of lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF were measured by anti-BDNF sandwich-ELISA using BDNF Emax Immunoassay system (Promega, Charbonnières, France) according to a protocol described previously. Additionally, western blots were used to detect extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation (see Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Behavioral testing

The originality of our protocol lies in the fact that the same cohort of animal was tested in different behavioral paradigms of anxiety and depression according to a procedure described previously.5 Behavioral procedure starts with the less stressful paradigm and finishes with the most stressful one. So each animal, over 1 week, was successively tested in the elevated plus maze (EPM), the novelty suppressed feeding (NSF), the tail suspension test (TST) and the splash test (ST) paradigm. A 2-day period between each test was respected (Supplementary Figure S1). Detail of these tests as well as x-irradiation procedure can be retrieve in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Immunohistochemistry

Ki67 labeling for proliferation study

We first looked at proliferation using Ki-67 as a marker for cell division. Ki-67, a nuclear protein expressed in all phases of the cell cycle except for G0, can be used as an endogenous marker alternative to bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation.23

BrdU labeling for survival study

Mice were administered with BrdU (150 mg kg−1, i.p. dissolved in saline), twice a day during 3 days before the start of the treatment. After anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine (75 mg kg−1 ketamine; 10 mg kg−1 xylazine; i.p.), mice were perfused transcardially (cold saline, followed by 4% cold paraformaldehyde at 4 °C). The identification of survival cells was performed by BrdU labeling (see Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Doublecortin labeling for maturation index and dendritic morphology studies

The identification of survival cells was performed by doublecortin (DCX) labeling (see Supplementary Materials and Methods). Once performed, DCX+ cells were subcategorized according to their dendritic morphology: DCX+ cells with no tertiary dendritic processes and DCX+ cells with complex, tertiary dendrites. The maturation index was defined as the ratio of DCX+ cells possessing tertiary dendrites over the total DCX+ cells.

Intracerebral electrophysiology

Mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg kg−1; i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (using the David Kopf mouse adaptor) with the skull positioned horizontally. Micropipettes were positioned on the lambda and lowered into the dorsal raphe (DR), usually attained at a depth of between 2.5 and 3.5 mm from the brain surface.22 The presumed DR 5-HT neurons were then identified accordingly using the following criteria: a slow (0.5–2.5 Hz) and regular firing rate and a long duration, positive action potential.24 Changes in the firing activity were expressed as percentages of baseline firing rate.

Intracerebral microdialysis

Mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg kg−1; i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (using the David Kopf mouse adaptor) with the skull positioned horizontally. Anesthetized mice were implanted with probes located in the hippocampus and DR. The stereotaxic coordinates for the hippocampus were (in mm from bregma): AP −2.5, L ±2.5, V −2.5 and for the DR (in mm from lambda): AP 0, L 0, V −3.5 (according to Paxinos and Franklin22). Active lengths of the microdialysis probes in the hippocampus and DR were 1.5 and 1 mm, respectively. Microdialysis experiments were conducted following a protocol previously described in our laboratory.25 These basal values were calculated for each mouse before the challenge of fluoxetine or vehicle. Dialysate samples were analyzed for 5-HT by high-performance liquid chromatography method (limit of sensitivity≈0.5 fmol per sample; signal-to-noise ratio=2). At the end of the experiments, localization of microdialysis probes was verified histologically.

8-Hydroxy-N,N-dipropyl-2-aminotetralin-induced hypothermia

Body temperature was assessed intrarectally, using a lubricated probe inserted ∼2 cm and a TH-5 Thermalert Monitoring Thermometer (Physitemp, Clifton, NJ, USA). Mice were singly housed in clean cages for 10 min, and three baseline body temperature measurements were taken. After the third baseline measurement, animals received 8-Hydroxy-N,N-dipropyl-2-aminotetralin (8-OH-DPAT) (100 μg kg−1; subcutaneous (s.c.)) and body temperature was monitored every 10 min for a total of 60 min. Decreases in body temperatures were represented as a change from the mean baseline measurement.

Drugs and administration

Fluoxetine (18 mg kg−1 per day) was purchased from ANAWA (Wangen, Switzerland) and administered in the drinking water in opaque bottles. For electrophysiological and microdialysis studies, 8-OH-DPAT (100–400 μg kg−1; s.c.), WAY100635 (N-[2-[4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl]-N-(2-pyridyl)cyclohexanecarboxamide) (300 μg kg−1; s.c.) and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France).

Statistical analysis

For all experiments, statistical analysis (StatView 5.0 Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA) used mean±s.e.m. Two-way analysis of variance with pre-treatment (lenti-GFP vs lenti-BDNF) and treatment (vehicle vs fluoxetine) factors was used followed by Fisher Protected Least Significance Difference post hoc test. In the irradiation experiments of lenti-BDNF mice, a two-way analysis of variance with irradiation (sham vs X-ray) and treatment (vehicle vs fluoxetine) factors was applied. Finally, hypothermic responses induced by 8-OH-DPAT were compared using a three-way analysis of variance with repeated measures. In specific cases, a Student's t-test was used to compare two groups of mice. Significant level was set at P<0.05. The detail of the statistical analysis for each figure is depicted in Supplementary Table S1.

Results

Validation of BDNF overexpression in the hippocampus of adult mice

The ability of the BDNF-engineered lentiviral vector to induce a detectable production of BDNF in the hippocampus was determined using ELISA. A significantly higher concentration of BDNF was observed in lenti-BDNF mice compared with control lenti-GFP mice treated with vehicle (P<0.001; Figure 1a). The administration of fluoxetine significantly increased the concentration of BDNF in the control lenti-GFP (P<0.01) but not in the lenti-BDNF mice (P>0.05; Figure 1a).

We next examined whether the BDNF-engineered lentiviral vector increased the levels of activated (phosphorylated) ERK and Akt in the rat hippocampus as an indirect marker of BDNF secretion. A significant activation of both ERK and Akt was detected in lenti-BDNF mice compared with control lenti-GFP mice (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively; Figures 1b–d). When treated with fluoxetine, the activation of both kinases was significantly increased in lenti-GFP (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively) but not in lenti-BDNF mice (P>0.05 and P>0.05, respectively).

Validation of glial cell transduction with GFP and BDNF

The microinjection of lentiviral particles into the hippocampus resulted in diffuse GFP expression. We showed that GFP fluorescence obtained with this mokola-pseudotyped lentiviral vector was localized to the subgranular layer and hilus of the DG (Figures 1e and f), while no expression was detected outside the hippocampus. Transduced proteins were selectively expressed in astrocytes as demonstrated by overlapping of GFP and GFAP immunostaining, whereas no GFP expression was detected in neurons located in the granular layer (Figure 1f; Supplementary Figure S2).

Behavioral response in lenti-BDNF adult mice administered the vehicle or fluoxetine

Given the ability of lentiviral vector to promote the production and release of BDNF from astrocytes, we therefore assessed the behavioral consequences of such manipulation in a battery of sensitive tests to the chronic administration of fluoxetine through neurogenesis-independent (EPM, TST and ST) and neurogenesis-dependent (NSF) mechanism of action.5

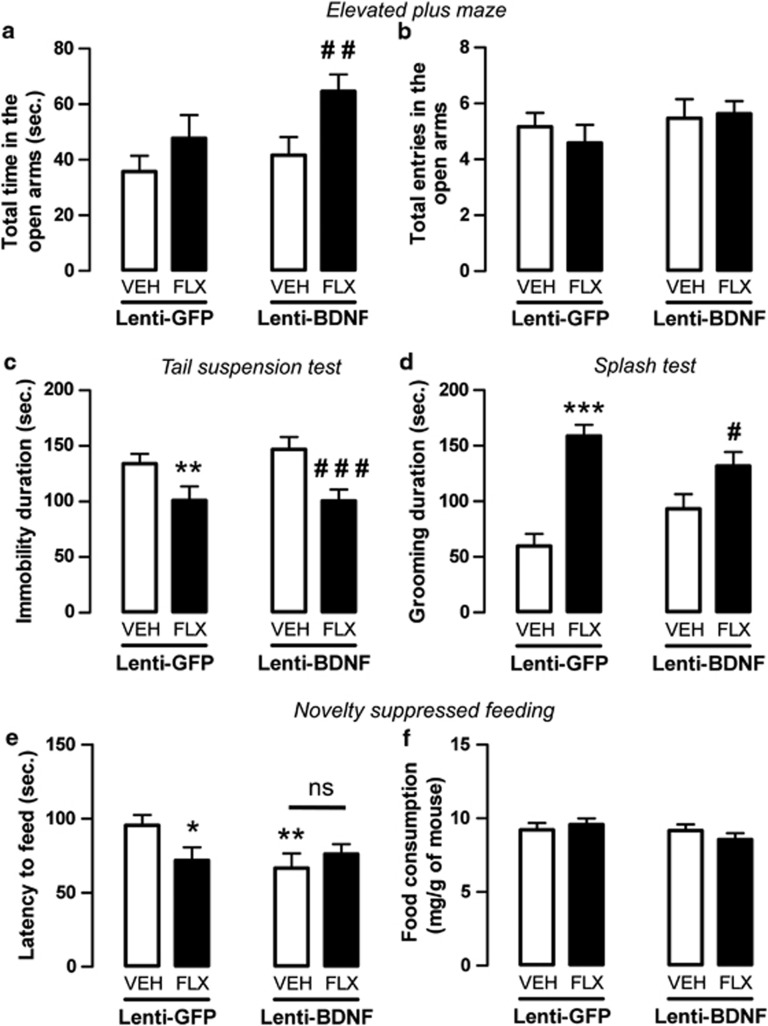

In the EPM, the time spent in the open arms was unaltered in lenti-BDNF mice compared with the control lenti-GFP mice treated with vehicle (P>0.05). Nevertheless, in response to fluoxetine, a significant increase was observed in the lenti-BDNF mice (P<0.01; Figure 2a) but not in lenti-GFP mice (P>0.05; Figure 2a) compared with their respective control groups treated with vehicle. The total entries in the open arms (Figure 2b) did not differ between the groups.

Figure 2.

Anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activity of fluoxetine in adult mice displaying an overexpression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in hippocampal astrocytes. (a, b) Anxiolytic-like effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks in the elevated plus maze (EPM) test. Anxiety is measured as mean±s.e.m. of time spent in the open arms in seconds (a). Locomotor activity is measured as mean±s.e.m. of number of entries in the open arms (b). (c, d) Antidepressant-like effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks evaluated in the tail suspension test (TST) (c) and splash test (d). Depression is measured as mean±s.e.m. of the immobility time or grooming duration in seconds. (e, f) Anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effects of BDNF overexpression in adult hippocampal astrocytes in mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks evaluated in the novelty suppressed feeding (NSF) test. (e) Mean±s.e.m. of latency to feed in seconds. (f) Mean±s.e.m. of food consumption (in mg g−1 of mice). In all tests: n=10–20 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-GFP (green fluorescent protein) mice administered with vehicle for 4 weeks. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle. NS, not significant.

With respect to behavioral paradigms developed to characterize antidepressant-like responses, in the TST our results showed that the duration of immobility was not altered in the control lenti-BDNF mice compared with the control lenti-GFP mice (P>0.05; Figure 2c). However, fluoxetine significantly decreased this parameter in both the lenti-GFP mice (P<0.01) and the lenti-BDNF mice (P<0.001). This antidepressant-like response to fluoxetine did not differ the lenti-GFP and the lenti-BDNF groups (P>0.05; Figure 2c). Similarly, in the ST fluoxetine increased grooming behaviors in both lenti-GFP (P<0.001) and lenti-BDNF mice (P<0.05) compared with their respective control groups administered the vehicle, while no differences between the lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF groups were detected (P>0.05; Figure 2d).

In a last series of experiments, in the same animals, we assessed the impact of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes in the NSF. We showed that the latency to feed was significantly decreased in the lenti-BDNF mice compared with the control lenti-GFP mice (P<0.01; Figure 2e). When treated with fluoxetine, the latency to feed was significantly decreased in lenti-GFP (P<0.05), but not in lenti-BDNF mice compared with their respective control groups (P>0.05). At the end of the test, the mice were immediately transferred to their home cages, where food consumption was measured for 5 min. This parameter used as a relative control for animal hunger and body weight did not differ between groups (Figure 2f; Supplementary Figure S3A).

Hippocampal neurogenesis in lenti-BDNF adult mice administered the vehicle or fluoxetine

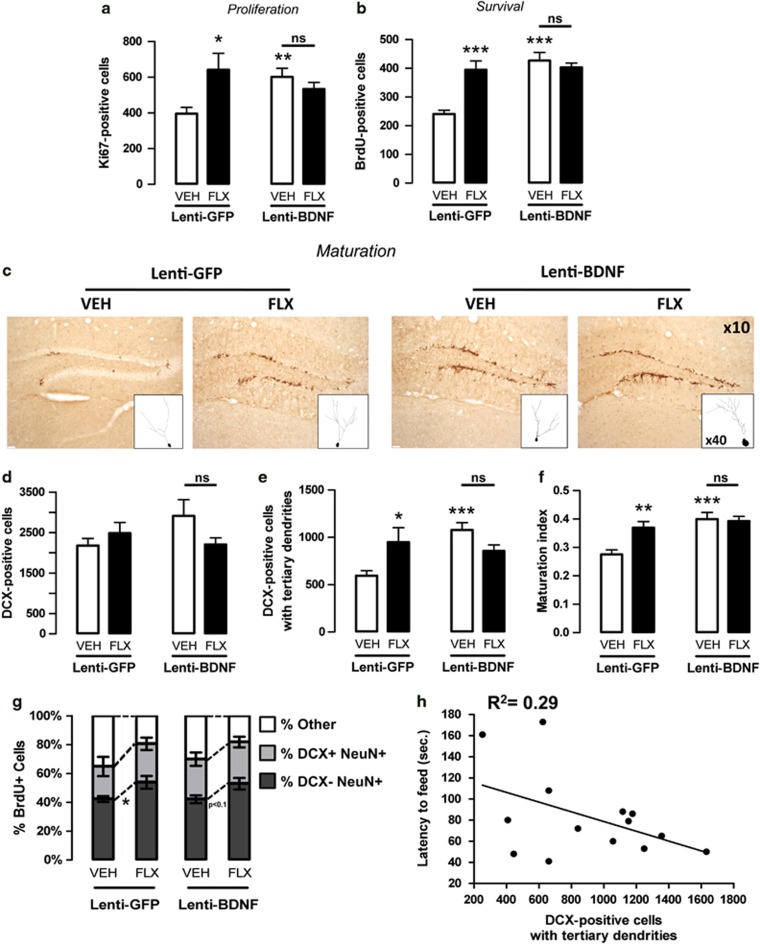

To further investigate the cellular mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of BDNF, we evaluated the impact of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes on adult hippocampal neurogenesis, which has been proposed as relevant for antidepressant action.1, 5 The BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes induced a significant proliferation of progenitor cells as shown by an increase in the number of Ki67-positive cells in the lenti-BDNF mice compared with the control lenti-GFP mice (P<0.01; Figure 3a). Fluoxetine also significantly increased this proliferation in lenti-GFP (P<0.05), but not in lenti-BDNF mice (P>0.05; Figure 3a) compared with their respective control groups treated with vehicle. A similar profile was observed for cell survival (Figure 3b) and the maturation of young neurons, particularly the number of DCX-positive cells with tertiary dendrites and the maturation index (Figures 3d–f).

Figure 3.

Neurogenesis in response to fluoxetine in adult mice displaying an overexpression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in hippocampal astrocytes. (a) Ki-67 labeling to examine the effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks on cell proliferation. Values are mean±s.e.m. of Ki67-positive cell counts (n=5–6 per group). (b) BrdU (150 mg kg−1) was given twice a day for 3 days before drug treatment to examine the effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks on cell survival. Values are mean±s.e.m. of BrdU-positive cell counts (n=5–6 per group). (c–f) Effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks. (c) Histological slices of the dentate gyrus showing doublecortin (DCX) immunostaining in each experimental group ( × 10) with 3D drawing of representative DCX-positive cells with dendritic complexity ( × 40). Total DCX-positive cells (d), DCX-positive cells with tertiary dendrites (e) as an index of young neurons maturation and maturation index (f) (n=8–10 per group). (g) Proportion of BrdU+NeuN+ cells that are DCX+ or DCX− (percentage of BrdU cells) as an index of maturity. (h) Correlation between behavioral response in the NSF and the number of DCX-positive cells with tertiary dendrites. Each point represents a lenti-BDNF mouse selected on the basis of its participation of both behavioral and immunohistochemical studies. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice administered with vehicle. NS, not significant.

We also examined the relative ‘maturity' of BrdU+NeuN+ cells according to whether they express DCX. The number of mature BrdU+ granule cells (BrdU+NeuN+DCX−) corresponding to young neurons increased in response to fluoxetine in the control lenti-GFP (P<0.05) and lenti-BDNF mice, although the increase was not statistically significant in the latter group (P<0.1). These results indicate that the chronic fluoxetine administration similarly changed the fate determination of early progenitors in lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice (Figure 3g).

In an attempt to correlate the anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effect of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes in the NSF with neurogenesis, we showed in lenti-BDNF mice (treated with vehicle or fluoxetine) that the lower the latency to feed, the higher the number of DCX+ cells with tertiary dendrites. Although results did not reach statistical significance (P<0.1 with an R2=0.29; Figure 3h), they strongly suggested a neurogenesis-dependent effect of BDNF overexpression in the NSF. In marked contrast, the results obtained from the EPM and the TST tests in lenti-BDNF mice did not support this correlation (P=0.8 in both tests with R2=0.01 and R2=0.01, respectively; Supplementary Figure S4).

Behavioral response in lenti-BDNF adult mice administered the vehicle or fluoxetine after the disruption of neurogenesis

To confirm the possibility that BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes produced anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effects through neurogenesis-dependent and neurogenesis-independent mechanisms, we examined whether the ablation of neurogenesis through X-irradiation, which does not affect glial cells density or hippocampal morphology,1, 26 blocked or attenuated the behavioral responses observed in lenti-BDNF mice in a new batch of animals (Figure 4; Supplementary Figure S5).

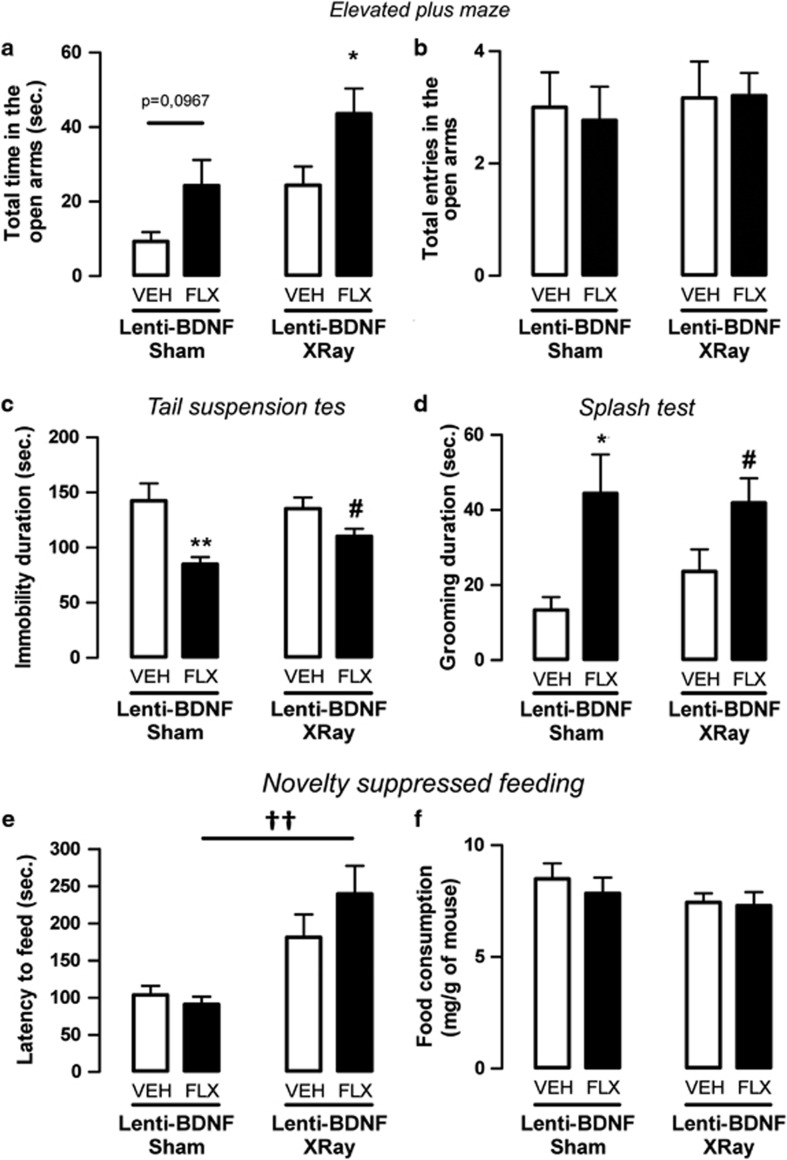

Figure 4.

Effect of X-ray on fluoxetine response in adult mice with an overexpression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in hippocampal astrocytes. (a, b) Anxiolytic-like effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks in the elevated plus maze (EPM) test. Anxiety is measured as mean±s.e.m. of time spent in the open arms in seconds (a). Locomotor activity is measured as mean±s.e.m. of number of entries in the open arms (b). (c, d) Antidepressant-like effects of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks evaluated in the tail suspension test (TST) (c) and splash test (d). Depression is measured as mean±s.e.m. of the immobility time or grooming duration in seconds. (e, f) Anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effects of BDNF overexpression in adult hippocampal astrocytes in mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks evaluated in the novelty suppressed feeding (NSF) test. (e) Mean±s.e.m. of latency to feed in seconds. (f) Mean±s.e.m. of food consumption (in mg g−1 of mice). In all tests: n=10–15 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01: significantly different from sham lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle. #P<0.05: significantly different from X-ray lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle. ††P<0.01: significantly different from lenti-GFP (green fluorescent protein) mice administered with fluoxetine.

In the EPM, the application of X-irradiation mice did not alter the effect of fluoxetine relative to sham mice (P<0.05). In addition, the increase in time spent in open arms induced by fluoxetine treatment was not different between sham and X-ray-treated lenti-BDNF mice (P>0.05; Figure 4a). The total entries in open arms (Figure 4b) did not differ between groups.

In the TST and ST, fluoxetine produced antidepressant-like activities in both sham and X-ray-treated mice (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively, in the TST and P<0.05 and P<0.05, respectively, in the ST; Figures 4c and d). Taken together, these results suggest that fluoxetine has a neurogenesis-independent effect on these behavioral paradigms.

In NSF, the application of x-irradiation on lenti-BDNF mice administered the vehicle lowered the anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like response, as indicated by the tendency to increase the latency to feed compared with sham mice (P=0.1). Similarly, in lenti-BDNF mice administered fluoxetine, x-ray treatment prevented the decrease in the latency to feed observed in the sham mice (P<0.01), confirming that the behavioral effect of BDNF overexpression alone or in combination with fluoxetine requires neurogenesis to produce behavioral effects in this test (Figure 4e). Food consumption and body weight did not differ between the groups (Figure 4f; Supplementary Figure S3B).

Changes in presynaptic serotonergic neuronal activity in lenti-BDNF mice treated with vehicle or fluoxetine

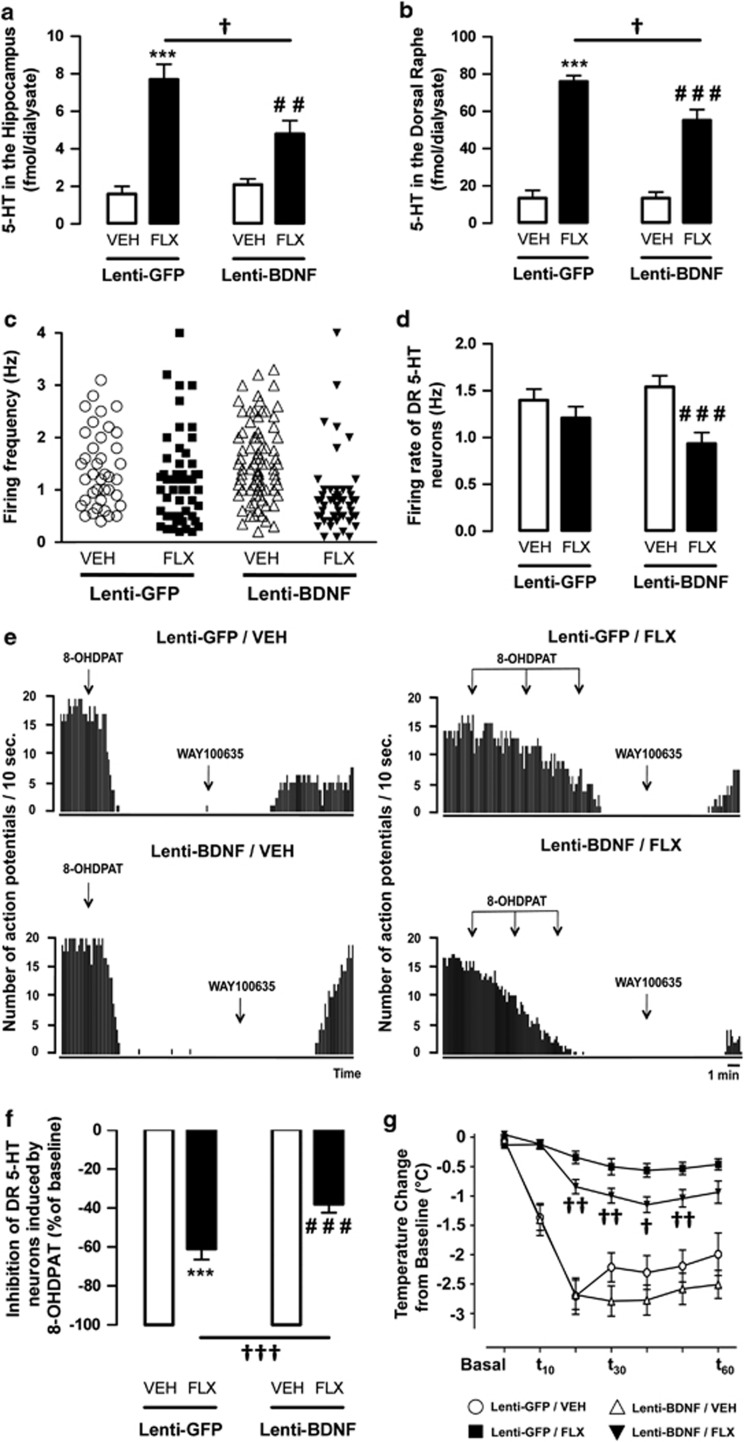

Extracellular levels of 5-HT in the hippocampus and DR

We then investigated whether the overexpression of BDNF in hippocampal astrocytes affected the local extracellular levels of 5-HT using in vivo intracerebral microdialysis. Figure 5a shows that the extracellular 5-HT levels in the hippocampus were not modified in the lenti-BDNF mice compared with the control lenti-GFP mice. Fluoxetine enhanced hippocampal 5-HT outflow in both lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered fluoxetine compared with their corresponding group administered the vehicle (P<0.001 and P<0.001). Nevertheless, the enhancement of 5-HT outflow was significantly lower in the hippocampus of lenti-BDNF compared with lenti-GFP mice (P<0.05). Similar neurochemical profile was observed at the somatodendritic level, that is, in the DR (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes of adult mice administered with vehicle or fluoxetine on serotonergic neuronal activity. (a, b) Extracellular levels of serotonin (5-HT) in the hippocampus and dorsal raphe (DR). Values are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of 5-HT levels in the hippocampus (fmol per 20 μl) (a) or in the DR (fmol per 10 μl) (b) of lenti-GFP (green fluorescent protein) and lenti-BDNF mice administered vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks (n=5–10 mice per group). (c, d) Electrophysiological activity of DR 5-HT neurons. (c) Scattergram depicting the firing frequency of all spontaneously active 5-HT neurons encountered during systematic electrode descents through the DR of lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks (n=4–5 mice per group). Lenti-GFP vehicle (39 cells recorded), Lenti-GFP fluoxetine (50 cells recorded), lenti-BDNF vehicle (81 cells recorded) and lenti-BDNF fluoxetine (52 cells recorded). (d) Values are mean±s.e.m. of firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons in lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle or fluoxetine. (e–g) Functional activity of 5-HT1A autoreceptor in the DR. (e) Representative integrated firing rate histograms illustrating the effect of 8-OH-DPAT administrations in each group of mice. Note that at the end of each recording, the inhibitory effect of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT is reversed by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY100635 (300 μg kg−1; subcutaneous (s.c.)). (f) Values are mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of decrease in DR 5-HT firing rate induced by the first dose of 8-OH-DPAT (100 μg kg−1; s.c.). (g) Hypothermic effects of 8-OH-DPAT (100 μg kg−1; s.c.) in lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle (VEH; p.o.) or fluoxetine (FLX, 18 mg kg−1 per day; p.o.) for 4 weeks. Values are mean±s.e.m. for each time point of body temperature change from baseline (°C). Baselines are calculated from the average from three temperature measures before 8-OH-DPAT administrations, each measure being performed with a 10-min interval (n=10–15 per group). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-GFP mice administered with vehicle for 4 weeks. ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-BDNF mice administered with vehicle. †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 and †††P<0.001: significantly different from lenti-GFP mice administered with fluoxetine.

Neuronal activity of DR 5-HT neurons

Next, we determined whether changes in the extracellular levels of 5-HT resulted from modifications of the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons. It has been shown previously that sub-chronic administration of SSRIs decreases the DR 5-HT firing rate, and a gradual recovery to baseline is observed after prolonged administration.27 In the present study, the mean firing activity of DR 5-HT neurons was similar between lenti-GFP mice administered the vehicle and lenti-GFP mice administered fluoxetine (1.4±0.1 vs 1.2±0.1 Hz; P>0.05, respectively; Figures 5c and d). In contrast, in lenti-BDNF mice administered fluoxetine, the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons was significantly lower than that obtained in lenti-BDNF mice administered the vehicle (0.9±0.1 vs 1.5±0.09 Hz; P<0.001). Thus, in lenti-BDNF mice, DR 5-HT neurons did not return to baseline as rapidly as lenti-GFP mice in response to fluoxetine treatment.

Functional status of presynaptic 5-HT 1A autoreceptor in the DR

To address the possibility that the decreased 5-HT neurotransmission in lenti-BDNF mice administered fluoxetine was associated with a reduced desensitization of the inhibitory 5-HT1A autoreceptor, we examined the ability of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT to decrease the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons (Figures 5f and g). A marked inhibition of DR 5-HT neuronal activity was observed in the control lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered the vehicle. Consistent with a functional desensitization of the 5-HT1A autoreceptor, the ability of 8-OH-DPAT to suppress 5-HT neuronal firing activity was attenuated in lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered fluoxetine compared with their respective control group (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively; Figures 5f and g). However, in fluoxetine-administered mice, the ability of 8-0H-DPAT to suppress DR 5-HT neuronal activity was lower in lenti-BDNF than in lenti-GFP mice (P<0.001).

To further explore the functional status of the 5-HT1A autoreceptor, we evaluated the ability of 8-OH-DPAT to decrease body temperature.28 In the present study, the control lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered the vehicle displayed a robust hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT. The prolonged administration of fluoxetine attenuated this response in both lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice (Figure 5g). However, after fluoxetine treatment, the attenuation of 8-OH-DPAT-induced hypothermia was less pronounced in the lenti-BDNF mice than in the lenti-GFP mice (Figure 5g).

Discussion

Adaptations induced through the use of chronic antidepressants, most notably in the hippocampus, are related to the upregulation of neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF,7 which enhances adult neurogenesis.29 This phenomenon is believed to be involved in the therapeutic activity of SSRIs.1 As such, developing pharmacological or genetic strategies that stimulate the production and/or release of BDNF represents promising approaches for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. In physiological conditions, neurons are the primary source of BDNF in the brain whereas astrocytes have a role in the storage and secretion of this neurotrophic substance.30 Growing evidence suggests however that this cell type may also synthesize BDNF at functionally relevant levels under certain conditions such as neuronal lesion17 or inflammation-like conditions.31 Interestingly, it was recently proposed that astrocytes synthesize BDNF in vitro in response to SSRIs20, 32 and 5-HT/norepinephrine or 5-HT/norepinephrine/dopamine reuptake inhibitors.32 Such an event might have a significant role in the therapeutic activity of these classes of antidepressant drugs. The present study used a novel and efficient BDNF-gene transfer strategy to shift the tropism of lentiviral vectors toward astrocytes to determine whether these cells may be activated by SSRIs to promote the in vivo synthesis/release of BDNF. To our knowledge, although transgenic mice have been engineered to overexpress BDNF into astrocytes,31 this strategy is unique, notably due to the detargeting method using micro ribonucleic acid to eliminate residual expression of BDNF in neurons.21

In the hippocampus of mice injected with the Mokola vector, a high density of astrocytes was transfected. As expected, the intrahippocampal injection of the lentiviral vector significantly increased local BDNF levels and related signaling as shown by the stimulation of Erk and Akt phosphorylation. These data seemingly confirm that BDNF was overexpressed and secreted, even in the absence of fluoxetine treatment. Similarly, when fluoxetine was administered for 28 days in control lenti-GFP-transfected mice, a significant increase in BDNF levels and kinases activation was observed. These data are in agreement with the observation that the application of fluoxetine or paroxetine upregulates BDNF mRNA and protein levels in cultured cortical astrocytes or glioblastoma-astrocytoma cells.20, 33 They also suggest that SSRIs trigger a signal stimulating astrocytes, which in turn elicits the in vivo upregulation of BDNF in these cells. Given that the combination of fluoxetine with lenti-BDNF did not induce more pronounced effects on BDNF levels and kinases activation than those measured with either treatment alone, it can be assumed that SSRIs and astrocytic BDNF acted through a similar downstream mechanism. Alternatively, it is possible that BDNF overexpression masked fluoxetine-induced neuronal BDNF expression. However, the strong tendency of fluoxetine to potentiate lenti-BDNF-induced increase in hippocampal BDNF levels, Erk and Akt phosphorylation is not in favor of the latter hypothesis.

Because the Mokola lenti-vector efficiently stimulated hippocampal BDNF signaling, we examined whether these molecular changes, induced through lenti-BDNF alone or in combination with fluoxetine, modified the anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like responses of mice in various paradigms. One of the most remarkable results obtained herein was the fact that the overexpression of BDNF alone in hippocampal astrocytes produced anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activity in mice submitted to the NSF in relation to the stimulation of the adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus. These data are in agreement with previous findings showing that the fluoxetine-induced anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activity in the NSF requires hippocampal neurogenesis.1, 5 The good correlation between the behavioral response in this paradigm and the number of neurons with tertiary dendrites in lenti-BDNF mice along with the fact that the ablation of hippocampal neurogenesis compromised the behavioral effects of BDNF overexpression, strengthened the hypothesis that hippocampal astrocytic BDNF produces anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effects in a neurogenesis-dependent manner. Importantly, several studies have reported a positive association between the activation of BDNF/tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) signaling pathways, the upregulation of hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressant-like activity of SSRIs8, 34, 35, 36 but the neuronal and/or astrocytic source of this factor had yet to be determined. Because the antidepressant response might have involved an excitatory action on the density of glial cells,13, 37 we also investigated whether BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes alone or in combination with fluoxetine modified the density of local GFAP+ cells. Our results indicate that this parameter did not differ between groups (Supplementary Figure S6), thus ruling out the possibility that the secreted BDNF acted on astrocytes themselves (autocrine mechanism) to generate newborn neurons. This is in contrast with a recent study showing that hippocampal BDNF infusion partially rescues the local decreased GFAP expression in rats submitted to chronic mild stress.38 Such a discrepancy may be due to the use of non-stressed mice in the present study. Conversely, our results strongly suggest a paracrine-like mechanism where hippocampal astrocytes constitute a microenvironment stimulating the synthesis and release of BDNF responsible for the neurogenesis and anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like effect in the NSF.

Some behavioral effects of fluoxetine do not require neurogenesis, particularly in the EPM, TST and ST.5 Therefore, we assessed the impact of BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes in these paradigms. As expected, fluoxetine displayed a robust antidepressant-like activity in the TST and ST. However, BDNF overexpression within astrocytes had no effects in these paradigms. This result can be somewhat puzzling given that BDNF infusion in the hippocampus has been previously reported to improve behavioral parameters such as despair.39, 40 Several reasons may be advanced to explain these differences such as the strain of mice tested (129sV vs Swiss) or the part of the hippocampus where BDNF or lenti-BDNF virus was injected (dorsal vs ventral). Alternatively, it is possible that chronic overexpression of BDNF produced TrkB receptor desensitization, whereas acute injection failed to do so. In the EPM, the overexpression of BDNF did not produce anxiolytic-like behavior. There is, however, accumulating evidence that hippocampal BDNF has a role in anxiety. For example, mice exhibiting decreased BDNF secretion or possessing a truncated isoform of its preferential TrkB receptor, most notably in newborn neurons,41 displayed an increased level of anxiety,42, 43 suggesting that the facilitation of BDNF/TrkB signaling is required for anxiolysis. Although the present study did not report an anxiolytic-like effect of BDNF overexpression alone in hippocampal astrocytes, an anxiolytic-like activity of fluoxetine was unveiled specifically in the group of BDNF-transfected mice. These results are consistent with previous findings showing that SSRIs produce anxiolysis after the intrahippocampal injection of BDNF.39 They are also in agreement with initial data reporting that fluoxetine was unable to reverse increased anxiety-related behaviors in BDNF+/− mice.42 Therefore, it appears that the overexpression of BDNF in hippocampal astrocytes favored the anxiolytic-like activity of SSRI and this property did not require neurogenesis because it was insensitive to X-irradiation. It is noteworthy that the neurochemical and behavioral effects observed in the present study might have resulted from viral infection that has been shown previously to cause reactive astrocytosis and neuroinflammation.44, 45 However, it seems unlikely that lenti-GFP alone increased BDNF signaling since the value of BDNF levels obtained in the present study was quite similar to that previously published by our group in control mice.46 Moreover, we demonstrated that the lenti-GFP alone was devoid of behavioral activity (Supplementary Figure S7) thereby excluding the possibility of glial generation of inflammatory molecules that would have modified behavioral parameters.

To determine a putative mechanism by which BDNF overexpression in hippocampal astrocytes regulated the anxiolytic-like activities of fluoxetine in the EPM, we directed our research on the regulation of the serotonergic system. The overexpression of BDNF in hippocampal astrocytes did not modify extracellular 5-HT concentrations in the hippocampus or DR. However, consistent with previous findings,47 an increase in extracellular 5-HT concentrations was detected in response to the chronic administration of fluoxetine in both lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice. This neurochemical effect was, however, less pronounced in the latter group of mice, suggesting that the release of BDNF from hippocampal astrocytes constituted a negative signal on 5-HT neurons. These results were confirmed from the observation that in lenti-BDNF mice, a challenge of fluoxetine significantly increased hippocampal extracellular levels of 5-HT but this neurochemical response was significantly lower than in lenti-GFP mice (Supplementary Figure S8).

Because the ability of SSRIs to enhance 5-HT release is strongly dependent on the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons,48 we determined how neurochemical changes were reflected at the electrophysiological level. No changes in the basal firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons were detected in lenti-BDNF mice administered the vehicle. Conversely, in response to fluoxetine treatment, the firing rate was lower in lenti-BDNF mice than in lenti-GFP mice, and this was reminiscent of the neurochemical data. The acute or sub-chronic administration of SSRIs typically reduces the neuronal activity of DR 5-HT neuronal activity in rodents;49 therefore, the electrophysiological response reported herein after 28 days of treatment could be interpreted as a complete recovery to the basal firing rate in lenti-GFP mice. Importantly, when fluoxetine was administered in lenti-BDNF-transfected mice, this recovery of firing seemed partial and might explain the reduced increase in hippocampal and DR extracellular 5-HT levels. It is well known that SSRI-induced progressive return to basal DR 5-HT firing rate results from progressive 5-HT1A autoreceptor functional desensitization.50 Hence, we explored the functional status of this 5-HT1A autoreceptor in lenti-GFP and lenti-BDNF mice administered fluoxetine. Using two distinct methods, we demonstrated that the degree of 5-HT1A autoreceptor desensitization induced through fluoxetine treatment was blunted in lenti-BDNF mice; thus, this receptor was able to maintain a significant inhibitory influence on 5-HT neurons. These findings might seem puzzling because the overexpression of BDNF was restricted to the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure S1), while the electrophysiological and hypothermic responses to 8-OH-DPAT are distally regulated by the DR.28, 47 However, given the presence of the TrkB receptor on 5-HT neurons in rodents,39, 51 an axonal retrograde transport of BDNF from hippocampal 5-HT terminals to their cell bodies within the DR is conceivable, as previously shown following the local infusion of BDNF in this brain region52 and in the rat occipital or entorhinal cortex.53 In addition, because in vitro and in vivo evidence demonstrates that BDNF modulates the 5-HT system, particularly through the induction of the serotonergic phenotype,54, 55 metabolism56, 57 and axonal sprouting in the adult brain,58, 59 we postulate that the overexpression of BDNF in hippocampal astrocytes might have resulted in the remodeling and growth of 5-HT dendrites in the DR, thereby increasing the density of the inhibitory 5-HT1A autoreceptor in response to fluoxetine. Such a mechanism might have participate to maintain an inhibitory feedback induced on the 5-HT system leading to an attenuation of extracellular 5-HT levels, which is supposed to favor anxiolytic-like response. This hypothesis is of particular interest since a recent study has demonstrated that mice displaying a high density of 5-HT1A autoreceptor display an attenuated response to stress and a lower extracellular levels of 5-HT in the hippocampus after fluoxetine treatement.28 Moreover, several pieces of evidence indicate that increased 5-HT tone can increase anxiety through activation of specific post-synaptic 5-HT receptors (for example, the 5HT1A, 5-HT2A/C or 5-HT3 subtypes) whereas genetic or pharmacological conditions that reduce 5-HT release would be a favorable condition for anxiolysis.60

Conclusion

The present data highlight a role for hippocampal astrocytes in the synthesis of BDNF in vivo. Given that in physiological conditions astrocytes express very low levels of BDNF, our results suggest that the increase in extracellular 5-HT levels induced by SSRIs might constitute a permissive signal to stimulate such a synthesis. In addition, it clearly appears that BDNF released from astrocytes acts on post-synaptic cells in the hippocampus to stimulate neurogenesis and mediate related anxiolytic-/antidepressant-like activities. Remarkably, BDNF also influence the neuronal activity of presynaptic neurons to prevent SSRI-induced increase in 5-HT tone. This mechanism might be a prerequisite for the potentiation of the anxiolytic-like effects of fluoxetine. Taken together, our results illustrate the concept of the tripartite synapse61 in which astrocytes may contribute in concert with neurons to increase BDNF/5-HT relationship, and have an important role in both neuronal functions and antidepressant-like activity (Supplementary Figure S9). It is noteworthy that one limitation of our study relies in the fact that some of the cells transfected, albeit weak, looked like transiently amplifying progenitor cells. We cannot rule out that the in vivo effects described herein were not mediated, at least in part, by such a residual overexpression of BDNF in non-glial cells. Our data require therefore further confirmation by using a complementary knockdown approach. If astrocytic BDNF effectively has a role in the antidepressant action then a decreased SSRI activity should be observed after its inactivation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the technical assistance of Valerie Dupont-Domergue and staff from the animal care facility of the « Institut Fédératif de Recherche-IFR141 » of the Paris XI University.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SW, Helmeste D, Leonard B. Is neurogenesis relevant in depression and in the mechanism of antidepressant drug action? A critical review. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;13:402–412. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.639800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini M, Underwood MD, Hen R, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, John Mann J, et al. Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2376–2389. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera TD, Dwork AJ, Keegan KA, Thirumangalakudi L, Lipira CM, Joyce N, et al. Necessity of hippocampal neurogenesis for the therapeutic action of antidepressants in adult nonhuman primates. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David DJ, Samuels BA, Rainer Q, Wang JW, Marsteller D, Mendez I, et al. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron. 2009;62:479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T. Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8856–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS. Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7539–7547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliaz D, Stall N, Dar DE, Zangen A. Knockdown of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in specific brain sites precipitates behaviors associated with depression and reduces neurogenesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:80–92. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Luikart BW, Birnbaum S, Chen J, Kwon CH, Kernie SG, et al. TrkB regulates hippocampal neurogenesis and governs sensitivity to antidepressive treatment. Neuron. 2008;59:399–412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen M, Lucas G, Ernfors P, Castren M, Castren E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressant drugs have different but coordinated effects on neuronal turnover, proliferation, and survival in the adult dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1089–1094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3741-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Duan W, Mattson MP. Evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for basal neurogenesis and mediates, in part, the enhancement of neurogenesis by dietary restriction in the hippocampus of adult mice. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1367–1375. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SH, Zhang ZJ, Guo YJ, Teng GJ, Chen BA. Hippocampal neurogenesis and behavioural studies on adult ischemic rat response to chronic mild stress. Behav Brain Res. 2008;189:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeh B, Di Benedetto B. Antidepressants act directly on astrocytes: Evidences and functional consequences. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;23:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeh B, Simon M, Schmelting B, Hiemke C, Fuchs E. Astroglial plasticity in the hippocampus is affected by chronic psychosocial stress and concomitant fluoxetine treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1616–1626. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Li B, Zhu HY, Wang YQ, Yu J, Wu GC. Clomipramine treatment reversed the glial pathology in a chronic unpredictable stress-induced rat model of depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:796–805. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O. Electroconvulsive seizures upregulate astroglial gene expression selectively in the dentate gyrus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;25:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudge JS, Pasnikowski EM, Holst P, Lindsay RM. Changes in neurotrophic factor expression and receptor activation following exposure of hippocampal neuron/astrocyte cocultures to kainic acid. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6856–6867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06856.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L, Fumagalli M, d'Adda di Fagagna F. Terminally differentiated astrocytes lack DNA damage response signaling and are radioresistant but retain DNA repair proficiency. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:582–591. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inazu M, Takeda H, Ikoshi H, Sugisawa M, Uchida Y, Matsumiya T. Pharmacological characterization and visualization of the glial serotonin transporter. Neurochem Int. 2001;39:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaman I, Fiumelli H, Magistretti PJ, Martin JL. Fluoxetine regulates the expression of neurotrophic/growth factors and glucose metabolism in astrocytes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2190-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colin A, Faideau M, Dufour N, Auregan G, Hassig R, Andrieu T, et al. Engineered lentiviral vector targeting astrocytes in vivo. Glia. 2009;57:667–679. doi: 10.1002/glia.20795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golmohammadi MG, Blackmore DG, Large B, Azari H, Esfandiary E, Paxinos G, et al. Comparative analysis of the frequency and distribution of stem and progenitor cells in the adult mouse brain. Stem Cells. 2008;26:979–987. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee N, Sivalingam S, Boonstra R, Wojtowicz JM. The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative markers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Vandermaelen CP. Intracellular identification of central noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons by a new double labeling procedure. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1786–1792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-12-01786.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard BP, Froger N, Hamon M, Gardier AM, Lanfumey L. Sustained pharmacological blockade of NK1 substance P receptors causes functional desensitization of dorsal raphe 5-HT 1A autoreceptors in mice. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1713–1723. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Yokoyama T, Sumitani K, Wang ZY, Yang W, Kusaka T, et al. The effect of prenatal X-irradiation on the developing cerebral cortex of rats. II: A quantitative assessment of glial cells in the somatosensory cortex. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard BP, Mansari ME, Murphy DL, Blier P. Altered response to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram in mice heterozygous for the serotonin transporter: an electrophysiological and neurochemical study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:349–361. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson-Jones JW, Craige CP, Guiard BP, Stephen A, Metzger KL, Kung HF, et al. 5-HT1A autoreceptor levels determine vulnerability to stress and response to antidepressants. Neuron. 2010;65:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels BA, Hen R. Neurogenesis and affective disorders. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1152–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergami M, Santi S, Formaggio E, Cagnoli C, Verderio C, Blum R, et al. Uptake and recycling of pro-BDNF for transmitter-induced secretion by cortical astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:213–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt A, Friedman HC, Caneda-Ferron B, Urban N, Moreno E, Rubio N, et al. BDNF regulation under GFAP promoter provides engineered astrocytes as a new approach for long-term protection in Huntington's disease. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1294–1308. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prickaerts J, De Vry J, Boere J, Kenis G, Quinton MS, Engel S, et al. Differential BDNF responses of triple versus dual reuptake inhibition in neuronal and astrocytoma cells as well as in rat hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9802-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelucci F, Croce N, Spalletta G, Dinallo V, Gravina P, Bossu P, et al. Paroxetine rapidly modulates the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein in a human glioblastoma-astrocytoma cell line. Pharmacology. 2011;87:5–10. doi: 10.1159/000322528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B, Xiong Z, Yang J, Wang W, Wang Y, Hu ZL, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of Ginsenoside Rg1 produced by activation of BDNF signaling pathway and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1872–1887. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Brazo J, Castro E, Diaz A, Valdizan EM, Pilar-Cuellar F, Vidal R, et al. Modulation of neuroplasticity pathways and antidepressant-like behavioural responses following the short-term (3 and 7 days) administration of the 5-HT4 receptor agonist RS67333. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:631–643. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes GE, Hill-Smith TE, Lucki I. Fluoxetine treatment induces dose dependent alterations in depression associated behavior and neural plasticity in female mice. Neurosci Lett. 2010;484:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.07.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M, Chowdhury GM, Terwilliger R, Newton SS, Duman RS, Behar KL, et al. Glial pathology in an animal model of depression: reversal of stress-induced cellular, metabolic and behavioral deficits by the glutamate-modulating drug riluzole. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:501–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Wang G, Wang H, Wang X. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) infusion restored astrocytic plasticity in the hippocampus of a rat model of depression. Neurosci Lett. 2011;503:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltheil T, Tanaka K, Reperant C, Hen R, David DJ, Gardier AM. Synergistic neurochemical and behavioural effects of acute intrahippocampal injection of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressants in adult mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:905–915. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Chen AC, Nakagawa S, Russell DS, Duman RS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioral models of depression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3251–3261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03251.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergami M, Rimondini R, Santi S, Blum R, Gotz M, Canossa M. Deletion of TrkB in adult progenitors alters newborn neuron integration into hippocampal circuits and increases anxiety-like behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15570–15575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803702105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ, et al. Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior. Science. 2006;314:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.1129663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carim-Todd L, Bath KG, Fulgenzi G, Yanpallewar S, Jing D, Barrick CA, et al. Endogenous truncated TrkB.T1 receptor regulates neuronal complexity and TrkB kinase receptor function in vivo. J Neurosci. 2009;29:678–685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5060-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashioka S. Antidepressants and neuroinflammation: can antidepressants calm glial rage down. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11:555–564. doi: 10.2174/138955711795906888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titeux M, Galou M, Gomes FC, Dormont D, Neto VM, Paulin D. Differences in the activation of the GFAP gene promoter by prion and viral infections. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;109:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvoen S, Pla P, Gardier AM, Saudou F, David DJ. Huntington's disease knock-in male mice show specific anxiety-like behaviour and altered neuronal maturation. Neurosci Lett. 2012;507:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainer Q, Nguyen HT, Quesseveur G, Gardier AM, David DJ, Guiard BP. Functional status of somatodendritic serotonin 1A autoreceptor after long-term treatment with fluoxetine in a mouse model of anxiety/depression based on repeated corticosterone administration. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:106–112. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.075796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P, de Montigny C. Modification of 5-HT neuron properties by sustained administration of the 5-HT1A agonist gepirone: electrophysiological studies in the rat brain. Synapse. 1987;1:470–480. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardier AM, Malagie I, Trillat AC, Jacquot C, Artigas F. Role of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the mechanism of action of serotoninergic antidepressant drugs: recent findings from in vivo microdialysis studies. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1996;10:16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P, de Montigny C, Chaput Y.A role for the serotonin system in the mechanism of action of antidepressant treatments: preclinical evidence J Clin Psychiatry 199051(Suppl14–20.discussion 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhav TR, Pei Q, Zetterstrom TS. Serotonergic cells of the rat raphe nuclei express mRNA of tyrosine kinase B (trkB), the high-affinity receptor for brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;93:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD, Alderson RF, Altar CA, DiStefano PS, Corcoran TL, Lindsay RM, et al. Differential distribution of exogenous BDNF, NGF, and NT-3 in the brain corresponds to the relative abundance and distribution of high-affinity and low-affinity neurotrophin receptors. J Comp Neurol. 1995;357:296–317. doi: 10.1002/cne.903570209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobreviela T, Pagcatipunan M, Kroin JS, Mufson EJ. Retrograde transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) following infusion in neo- and limbic cortex in rat: relationship to BDNF mRNA expressing neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1996;375:417–444. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961118)375:3<417::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumajogee P, Madeira A, Verge D, Hamon M, Miquel MC. Up-regulation of the neuronal serotoninergic phenotype in vitro: BDNF and cAMP share Trk B-dependent mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1525–1528. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumajogee P, Verge D, Darmon M, Brisorgueil MJ, Hamon M, Miquel MC. Rapid up-regulation of the neuronal serotoninergic phenotype by brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cyclic adenosine monophosphate: relations with raphe astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:481–487. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Boylan C, Fritsche M, Altar CA, Lindsay RM. BDNF increases monoaminergic activity in rat brain following intracerebroventricular or intraparenchymal administration. Brain Res. 1996;710:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Clark MS, Rind HB, Whittemore SR, Russo AF. BDNF induction of tryptophan hydroxylase mRNA levels in the rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52:149–158. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980415)52:2<149::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luellen BA, Bianco LE, Schneider LM, Andrews AM. Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with a loss of serotonergic innervation in the hippocampus of aging mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamounas LA, Altar CA, Blue ME, Kaplan DR, Tessarollo L, Lyons WE. BDNF promotes the regenerative sprouting, but not survival, of injured serotonergic axons in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 2000;20:771–782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00771.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon M. Neuropharmacology of anxiety: perspectives and prospects. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:36–39. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.