Abstract

Introduction

Centor criteria (fever >38.5°C, swollen, tender anterior cervical lymph nodes, tonsillar exudate and absence of cough) are an algorithm to assess the probability of group A β haemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) as the origin of sore throat, developed for adults. We wanted to evaluate the correlation between Centor criteria and presence of GABHS in children with sore throat admitted to our paediatric emergency department (PED).

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The emergency department of a large tertiary university hospital in Brussels, with over 20 000 yearly visits for children below age 16.

Participants

All medical records (from 2008 to 2010) of children between ages 2 and 16, who were diagnosed with pharyngitis, tonsillitis or sore throat and having a throat swab culture for GABHS. Children with underlying chronic respiratory, cardiac, haematological or immunological diseases and children who had already received antibiotics (AB) prior to the PED consult were excluded. Only records with a full disease history were selected. Out of a total 2118 visits for sore throats, 441 met our criteria. The children were divided into two age groups, 2–5 and 5–16 years.

Results

The prevalence of GABHS was higher in the older children compared to the preschoolers (38.7 vs 27.6; p=0.01), and the overall prevalence was 32%. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of GABHS for all different Centor scores within an age group. Likelihood ratios (LR) demonstrate that none of the individual symptoms or a Centor score of ≥3 seems to be effective in ruling in or ruling out GABHS. Pooled LR (CI) for Centor ≥3 was 0.67 (CI 0.50 to 0.90) for the preschoolers and 1.37 (CI 1.04 to 1.79) for the older children.

Conclusions

Our results confirm the ineffectiveness of Centor criteria as a predicting factor for finding GABHS in a throat swab culture in children.

Keywords: Paediatrics, Infectious diseases, Otolaryngology

Article summary.

Article focus

To evaluate the correlation between Centor criteria and presence of GABHS in children with sore throat admitted to our emergency department, in order to evaluate the value of this prediction rule.

Key messages

Results confirm the ineffectiveness of Centor criteria as a predicting factor for finding GABHS in a throat swab culture in children.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study is the large number of children included. The major limitation is the fact that not all children received a throat swab, thus introducing a selection bias.

Introduction

In 1981, Centor et al1 developed four criteria to predict the probability of the presence of Streptococcus pyogenes or group A β haemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) in a throat swab culture. When all four criteria (fever >38.5°C, swollen, tender anterior cervical lymph nodes, tonsillar exudate and absence of cough) are present, the probability of GABHS is just above 50%. When two or less criteria are present, the probability is below 15%. Hence, Centor criteria are often used as a tool to assess the absence of GABHS, rather than its presence.2–4 It should also be noted that these criteria were specifically developed for adults.1 More recently, McIsaac et al5 6 developed modified criteria, which add the age of the patient (+1 if age 3–14, 0 if age 15–44 and -1 if age ≥45), taking into account the fact that GABHS is more prevalent in the age group of 5–15 years.2 7–10 Still, several studies have shown that neither signs and symptoms, nor signs and symptoms combined as prediction rules, were reliable to distinguish between GABHS and non-GABHS pharyngitis.11–16

The administration of antibiotics used to be indicated, based on the incidence of non-suppurative complications (post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and reactive arthritis), after streptococcal pharyngitis, but a large Cochrane review by Del Mar et al17 states that the use of antibiotics (AB) in otherwise healthy individuals is no longer indicated, as not only has the incidence of non-suppurative complications disappeared in the developed world since the late 1960s but also antibiotics will not shorten disease duration or symptoms.17 18 With the possibility of the adverse effects of AB, the benefit to risk ratio no longer favours administering AB to otherwise healthy individuals with streptococcal pharyngitis.

Objectives

In our paediatric emergency department (PED), physicians are taught to follow the guidelines of the Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee (BAPCOC). BAPCOC guidelines are based on the review by Del Mar et al.17 And yet we found that, in our PED, in 2009 and 2010, of 1345 otherwise healthy children, 35% were prescribed AB (unpublished data). For general practitioners in Flanders, the prescription rate is as high as 50%, even without knowing whether or not the pharyngitis was caused by GABHS.2 As many clinicians tend to rely on signs and symptoms, rather than on a strep test or throat swab culture, we wanted to evaluate the correlation between Centor criteria and presence of GABHS in children with sore throat admitted to our PED, in order to evaluate the value of this prediction rule.

Patients and methods

This is a retrospective cohort study that was approved by the local ethics committee of UZ Brussel and took place at the emergency department at UZ Brussel, a large tertiary university hospital in Brussels, with over 60 000 yearly visits, of which one in three are children below age 16. Children are seen at the paediatrics section, by paediatric residents and emergency medicine residents, under full supervision of a board-certified paediatrician.

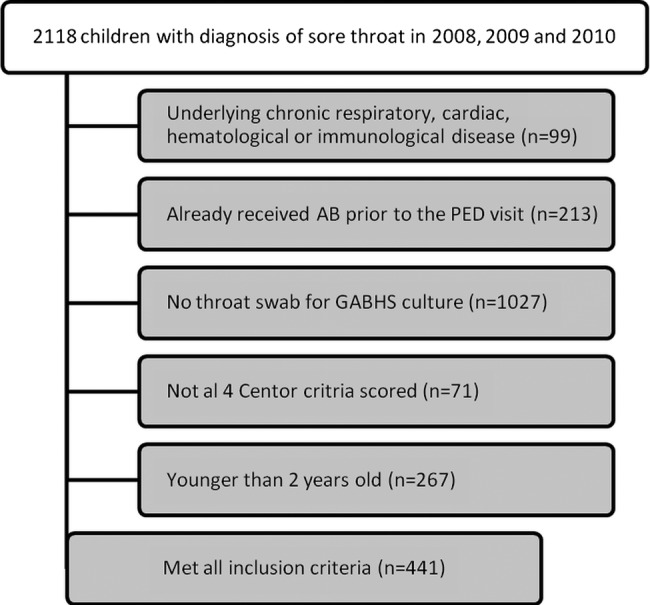

We analysed all medical records of children aged between 2 and 16 years who were admitted to our PED between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2010. All our records are digitalised and all diagnoses in our records are registered according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9) codes. All files of children who received a throat swab for GABHS culture with the following ICD-9 codes infectious mononucleosis (075), nasopharyngitis (460), pharyngitis (462), tonsillitis (463) and sore throat (784.1) were included for analysis. Children with underlying chronic respiratory, cardiac, haematological or immunological diseases and children who had already received AB prior to the PED consult were excluded. Only records with a full disease history were selected (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

We divided patients into 2 groups, preschoolers (≥2 and <5 years) and kids (≥5 and <16 years), as the prevalence of GABHS is different in both groups.

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc V.12.3.0 (MedCalc Software bvba, Mariakerke, Belgium). All data are presented as mean±standard deviation or as median (range), when not normally distributed. D’Agostino-Pearson K2 test was used for assessing normality of data. Spearman's rho test was used to calculate rank correlation coefficients.

Results

Out of all 2118 PED visits for sore throat, 441 (230 boys and 211 girls) met our criteria (graph 1). Median age (range) was 5 years (2–15.9). It was 3.3 years (2–4.9) in the preschoolers (n=286) and 7.6 (5–15.9) in the kids (n=155). Throat swab culture for GABHS was positive for 32% of the patients. In kids, the prevalence of GABHS was higher compared to the preschoolers (38.7 vs 27.6; p=0.01). Median age and gender distribution was not statistically significant between the included and excluded children.

The mean Centor score was similar between preschoolers and kids (2.6±0.9 vs 2.6±0.9; p=0.8). The mean (95% CI) presence of GABHS in our preschoolers was 45% (CI 28% to 63%) with <2 Centor criteria present, 33% (CI 24% to 43%) with 2, 23% (CI 15% to 31%) with 3 and 13% (CI 3% to 24%) with 4 criteria, respectively, present. In kids, this was 35% (CI 10% to 61%) when ≤1, 31% (CI 17% to 44%) when 2, 43% (CI 31% to 55%) when 3 and 45% (CI 21% to 69%) when 4 criteria were present (table 1).

Table 1.

Centor criteria and presence of GABHS

| Number of criteria present | <2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Number of preschoolers (2–4 years) | 33 | 96 | 113 | 44 |

| GABHS prevalence (95% CI, %) | 45 (28 to 63) | 33 (24 to 43) | 23 (15 to 31) | 13 (3 to 24) |

| Number of kids (5–15 years) | 17 | 49 | 69 | 20 |

| GABHS prevalence (95% CI, %) | 35 (10 to 61) | 31 (17 to 44) | 43 (31 to 55) | 45 (21 to 69) |

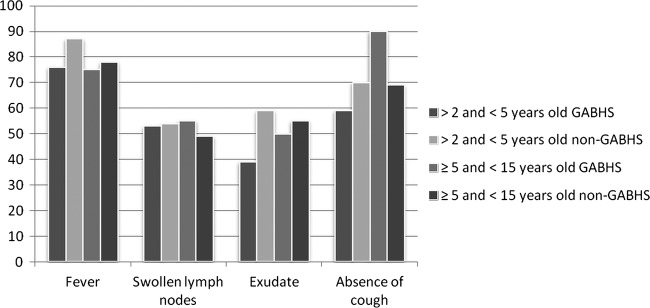

Preschoolers with a positive throat swab culture had significantly less often tonsillar exudate, compared to preschoolers (59% vs 39%; p=0.003) or kids (55% vs 39%; p=0.04) with a negative culture, but not compared to kids with a positive culture (50% vs 39%; p=0.2). Kids with a positive throat swab culture presented significantly more often with an absence of cough, compared to the other three groups (p<0.05). The occurrence of all other symptoms did not differ significantly between all the four groups (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence (%) of all four Centor criteria in children with a group A β haemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS)-positive and GABHS-negative throat swab culture, respectively.

Likelihood ratios (LR) for both age groups are shown in tables 2 and 3. Neither the individual symptoms nor a Centor score of ≥3 seems to be effective in ruling in or ruling out GABHS.

Table 2.

Correlation between clinical parameters and the presence of GABHS (2–4 years)

| Clinical parameter | Positive likelihood ratio (CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99) | 1.91 (1.13 to 3.26) |

| Tonsillar exudate | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.90) | 1.48 (1.16 to 1.88) |

| Swollen lymph nodes | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.25) | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.35) |

| Absence of cough | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.04) | 1.35 (0.96 to 1.90) |

| Centor ≥3 | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.90) | 1.50 (1.17 to 1.92) |

Table 3.

Correlation between clinical parameters and the presence of GABHS (5–15 years).

| Clinical parameter | Positive likelihood ratio (CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.15) | 1.13 (0.63 to 2.02) |

| Tonsillar exudate | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.25) | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.55) |

| Swollen lymph nodes | 1.11 (0.82 to 1.51) | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.26) |

| Absence of cough | 1.30 (1.11 to 1.52) | 0.33 (0.14 to 0.74) |

| Centor ≥3 | 1.37 (1.04 to 1.79) | 0.67 (0.45 to 0.99) |

We note that the children included in our results (compared to those excluded) more often had a tonsillar exudate (53.3% vs 32.7%; p<0.0001), fever (81.6 vs 74.4%; p=0.002) and swollen cervical lymph nodes (53.1 vs 43.4%; p<0.05), and thus a higher Centor score (2.2 vs 2.6; p<0.0001).

Discussion

Our results confirm the higher prevalence of GABHS in children between ages 5 and 15. The prevalence of GABHS in both our age groups is slightly higher compared to the results in the literature.5 19 20 This is probably due to selection bias: not all children with a sore throat had a throat swab culture for GABHS and our physicians seem to have several different reasons on which they base their decision of whether or not to take a throat swab culture.

In children between ages 2 and 5 with a Centor score below 2, we found a rather high prevalence of GABHS, which might be due to asymptomatic carriership.20 Also, in this group, a decrease in the prevalence of GABHS is seen with a higher Centor score. A possible explanation is the higher prevalence of viruses such as the Epstein-Barr virus, which also comes with fever, tonsillar exudate and swollen, tender cervical lymph nodes. With a prevalence of GABHS which is constant and comparable to the overall population prevalence, for all different Centor categories in children from 5 to 16 years of age, it is clear that, in children, Centor criteria are not a good tool to assess the probability of GABHS. With a combined likelihood ratio (95% CI) for Centor ≥ 3 of 0.67 (CI 0.50 to 0.90) for the preschoolers and 1.37 (CI 1.04 to 1.79) for the kids, our results are in line with the results of the meta-analysis of Shaikh et al16 who found a pooled LR (CI) for Centor ≥3 of 1.73 (CI 1.28 to 2.35).

Our results confirm that the Centor score is also insensitive to evaluate the absence of GABHS. In our group, children with <3 Centor criteria have a 72% probability for a negative culture for GABHS, which mirrors the average GABHS prevalence (30%) in this population.5 21 Even though the use of AB in streptococcal pharyngitis is disputed, physicians tend to have a low threshold to prescribe AB, judging only on clinical features, without knowing whether or not GABHS is the culprit (Roggen et al unpublished data).2 Our results confirm that, at least in children, Centor criteria are an unreliable tool to assess the probability of the presence of GABHS; thus, its use should be discouraged.

The strength of this study is the large number of children included. The major limitations of this study are the retrospective nature and the fact that not all children received a throat swab, thus introducing a selection bias, as children who had a throat swab had a higher Centor score.

Conclusion

Our results confirm the ineffectiveness of Centor criteria as a predicting factor for the presence or absence of GABHS in a throat swab culture in children from 2 to 15 years of age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms Annemieke Verholle, who keeps the databases with patient information and ICD-9 codes up to date, and Mr André Van Zeebroeck, who extracted the data from the laboratory of Microbiology.

Footnotes

Contributors: PIR, GVB, FG, DP and IH fulfil all three of the ICMJE guidelines for authorship. PIR was the principal investigator and lead writer. All authors helped to plan the study, evolve the analysis plans, interpret the data and critically revise successive drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethisch Comité UZ Brussel.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The unpublished data (as mentioned on line 4 in ‘objectives’) are from the article (which is currently being written) about the antibiotics prescription behaviour of physicians at our emergency department for otherwise healthy children with sore throat.

References

- 1.Centor R, Witherspoon J, Dalton H, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making 1981;1:239–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Meyere M, Matthys J. Acute keelpijn: WVVH-aanbeveling voor goede medische praktijkvoering. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zwart S, Rovers M, De Melker R, et al. Penicillin for acute sore throat in children: randomised, double blind trial. BMJ 2003;327:1324–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisno A, Peter G, Kaplan E. Diagnosis of strep throat in adults: are clinical criteria really good enough? Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:126–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIsaac W, Kellner J, Aufricht P, et al. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA 2004;291:1587–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIsaac W, Goel V, To T, et al. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ 2000;163:811–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent M, Celestin N, Hussain A. Pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:1465–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder B. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:880, 883–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruppert S. Differential diagnosis of common causes of pediatric pharyngitis. Nurse Pract 1996;21:38–42 44, 47–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin J. Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and streptococcal carriage in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2010;126:e557–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hossain P, Kostiala A, Lyytikäinen O, et al. Clinical features of district hospital paediatric patients with pharyngeal group A streptococci. Scand J Infect Dis 2003;35:77–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahin F, Ulukol B, Aysev D, et al. The validity of diagnostic criteria for streptococcal pharyngitis in Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines. J Trop Pediatr 2003;49:377–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer Walker C, Rimoin A, Hamza H, et al. Comparison of clinical prediction rules for management of pharyngitis in settings with limited resources. J Pediatr 2006;149:64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regoli M, Chiappini E, Bonsignori F, et al. Update on the management of acute pharyngitis in children. Ital J Pediatr 2011;37:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Silva K, Gunatunga M, Perera A, et al. Can group A beta haemolytic streptococcal sore throats be identified clinically? Ceylon Med J 1998;43:196–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaikh N, Swaminathan N, Hooper E. Accuracy and precision of the signs and symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis in children: a systematic review. J Pediatr 2012;160:487–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Mar C, Glasziou P, Spinks A. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;18(4 ) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BAPCOC Belgische gids voor anti-infectieuze behandeling in de ambulante praktijk—editie 2008. http://www.health.belgium.be/filestore/15616531/832250_BW_NL_01_84_IC_15616531_nl.pdf (accessed 4 Oct 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amir J, Shechter Y, Eilam N, et al. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis in children younger than 5 years. Isr J Med Sci 1994;30:619–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Top FH, Jr, Dudding BA, et al. Diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis: differentiation of active infection from the carrier state in the symptomatic child. J Infect Dis 1971;123:490–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worrall G. Acute sore throat. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:1961–2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.