Abstract

Objectives

Prompt assessment of consciousness levels is vitally important during the emergency care of stroke patients. The Japan Coma Scale (JCS) is a one-axis coma scale published in 1974 with outstanding simplicity. The hypothesis is that JCS is sufficient to predict stroke outcome. The aim of the study was to verify the predictability of JCS, which should help JCS attain international recognition.

Design

A cohort study.

Setting

A prefectural stroke registry.

Participants

We analysed 13 788 stroke patients identified from January 1999 to December 2009 inclusive in the entire Kyoto prefecture and registered in the Kyoto Stroke Registry (KSR).

Main outcome measures

We investigated the relationship between consciousness levels, based on JCS at stroke onset and activities of daily living (ADL) at 30 days or deaths within 30 days in a large population-based stroke registry. We calculated Spearman's coefficient for the correlation between JCS and the ADL scale, generated estimated survival curves by the Kaplan-Meier method and finally compared HRs for death within 30 days after onset, comparing patients with different conscious levels based on JCS.

Results

A total of 13 406 (97.2%) patients were graded based on JCS. JCS correlated to the ADL scale with Spearman's correlation coefficient of 0.61. HRs for death within 30 days were 1 (reference) (95% CIs), 5.55 (4.19 to 7.37), 9.54 (7.16 to 12.71) and 35.21 (26.10 to 44.83) in those scored as JCS0, JCS1, JCS2 and JCS3, respectively.

Conclusions

Using a single test of eye response, JCS has outstanding merits as a coma scale, that is, simplicity and applicability. The present study adds predictability for early outcome in stroke patients. JCS is valuable, especially in an emergency setting, when a prompt assessment of consciousness levels is needed.

Article summary.

Article focus

The Japan Coma Scale (JCS) is a one-axis coma scale published in 1974. It is so simple and easy to use that it has been established as a standard coma scale in Japan. Nevertheless, it has little recognition internationally. The aim of the study was to verify its predictability in stroke patients. We hope JCS will contribute to the medical profession and especially to emergency medical care.

Key messages

Using a single test of eye response, JCS has outstanding merits as a coma scale, that is, simplicity and applicability. The present study adds predictability for early outcome in stroke patients. JCS is valuable, especially in an emergency setting when a prompt assessment of the consciousness level is needed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study is based on a large stroke registry and JCS has been used widely in Japan.

There are as yet few studies on JCS and on the activity of daily life scale in scientific international journals.

Introduction

Prompt assessment of consciousness levels is vitally important during the emergency care of stroke patients. Currently, there is no perfect coma scale, and requirements for a better scale include:

Simplicity: ease of assessment, ease of recording, and ease of sharing with medical and comedical staff.

Reliability: consistency among assessors.

Applicability: for any patient in any setting.

Predictability for the outcome.

The Japan Coma Scale (JCS) has become widely used in Japan since it was first published in 1974.1–3 Ohta4 launched a national survey on craniotomy for ruptured cerebral aneurysms, and described JCS to define the consciousness level to be included in the survey at the first meeting of the Society on Surgery for Cerebral Stroke, which was held at Miyagi, Japan (Sakunami Kanko Hotel) on 13–14 May 1972. At that meeting he also organised a team to evaluate the scale because there was then no standardised coma scale.

JCS was based on his study of factors affecting the prognosis of ruptured aneurysm patients after surgical interventions.5 It was called the three group 3 grade method at first and then the ‘3-3-9 method’,1 6 since the detailed version of the scale composed of four categories: alert, 1-digit, 2-digit and 3-digit codes, with each digit code having three subcategories (1, 2 and 3 in the 1-digit code, 10, 20 and 30 in the 2-digit code, and 100, 200 and 300 in the 3-digit code).1 It had 10 grades in total: alert plus 9 (3 by 3) grades. This version of JCS included a motor response test in the 3-digit code patients and three special conditions: restlessness, incontinence and apathy. The first full paper was accepted on 30 November 1973.1

In this study, we applied the simple JCS without subcategories, which is commonly used in Japan.

An outstanding feature of JCS is its simplicity, which has prompted both the prehospital personnel and in-hospital staff to use the scale. JCS enables prompt communication among emergency service staff and hospital staff, as well as among nurses and physicians. However, JCS's predictability of the outcome has not yet been clarified. The lack of evidence of its predictability may have prevented JCS from attaining international recognition.

Our hypothesis is that consciousness levels categorised by JCS should correlate with the severity of stroke and therefore should predict the outcome of stroke. If the predictability of JCS is demonstrated, it should be reappraised as a prompt international coma scale. Although we have the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), which was also published in 1974,7 8 it would be more pragmatic to have a simpler coma scale, especially in an emergency. The major difference between GCS and JCS is that the former is a three-axis scale, whereas the latter is a one-axis scale.

The aim of the study was to verify that JCS predicts early outcome, including the levels of activity of daily life (ADL) and HRs for death, and, consequently, to reintroduce this simple coma scale to the world.

Materials and methods

We studied the relationship between the outcome at 30 days after stroke and the consciousness levels based on JCS at the onset of neurological impairment. We analysed all new stroke patients identified from January 1999 to December 2009 inclusive in the entire Kyoto prefecture and registered in the Kyoto Stroke Registry (KSR).9 Detailed information on KSR has been described previously.10 The diagnosis of stroke was confirmed by local neurologists and/or neurosurgeons according to the WHO definition.11 We categorised the patients into cerebral infarction, cerebral haemorrhage (CH), subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and others, based on the neurological findings, laboratory data and findings of CT, MRI and angiography.

We used the following definitions:

- Consciousness levels based on JCS encompassed four levels

- JCS0 (alert)

- JCS1 (not fully alert but awake without any stimuli)

- JCS2 (arousable with stimulation)

- JCS3 (unarousable)

- The ADL scale at 30 days after stroke onset included five levels

- ADL1 (No symptoms or no significant disability. Able to carry out all usual activities without help. Able to walk without a mobility aide.)

- ADL2 (Mildly disabled, or utilisation of mobility aide. Unable to carry out all usual activities without help. Unable to walk without mobility aide.)

- ADL3 (Moderately disabled, or wheelchair-bound condition. Unable to walk without assistance.)

- ADL4 (Severely disabled, or bed-bound condition. Unable to use wheelchair without help.)

- ADL5 (Dead.)

Ethics statement

This research was performed in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This research was approved by the Board of Directors, the Kyoto Medical Association, the Department of Health and Welfare, Kyoto Prefecture and the Ethics Committee of the National Hospital Organization, Minami Kyoto Hospital. Since all identifying personal information was stripped from the secondary files before analysis, the boards waived the requirement for written informed consent from the patients involved.

Statistical analyses

The frequencies of characteristics among the four conscious levels were determined and evaluated for univariate associations by χ² analysis. Numerical data such as age and blood pressure were compared with Student t tests. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to identify the correlation between JCS and the ADL scale. We used the Kaplan-Meier method for curves of estimated survival, a log-rank test for comparisons of estimated survival among the JCS categories and the Cox proportional hazards regression for HRs for death. Adjustments for age, sex, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, histories of hypertension, arrhythmia and diabetes mellitus, stroke type and paresis were also utilised. Analyses were performed using SPSS V.19. All reported p values are two-sided.

Results

The characteristics of the patients are summarised in table 1. Data on age and sex were complete in all patients in the study cohort. The other characteristics had missing data in a few patients. The numbers of patients examined are shown in the tables.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the study cohort

| Characteristic | JCS0 (n=7676) | JCS1 (n=2619) | JCS2 (n=1602) | JCS3 (n=1509) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.7±12.3*123 | 73.4±12.3*3 | 73.6±14.2*3 | 72.3±14.0 |

| Sex (% of female, (n=female/male)) | 39.8 (3056/4620)*123 | 47.7 (1249/1370)*23 | 56.9 (911/691)*3 | 54.7 (826/683) |

| Subtype (cerebral infarction /CH/SAH, % (n)) | 78.9/15.7/5.4 (6048/1201/415)*123 | 57.7/35.2/7.1 (1508/921/185)*23 | 48.5/39.0/12.5 (774/622/200)*3 | 28.0/47.7/24.3 (421/716/365) |

| Systolic blood pressure | 159.3±28.2*123 | 162.7±31.7*3 | 163.6±33.3*3 | 167.4±42.1 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 87.0±17.1*123 | 88.0±19.0*3 | 88.6±20.6 | 89.8±24.4 |

| Paresis (%, (n=with/without)) | 67.0 (5085/2501)*123 | 78.2 (2014/561)*23 | 83.1 (1278/260)*3 | 89.2 (1060/128) |

| Hypertension history (%, (n=with/without)) | 64.5 (4724/2605)*123 | 61.0 (1476/942)*23 | 59.8 (857/576)*3 | 59.3 (755/518) |

| Arrhythmia history (%, (n=with/without)) | 14.5 (1058/6233)*123 | 23.3 (569/1870)*23 | 28.2 (412/1047)*3 | 20.1 (254/1010) |

| Diabetes mellitus history (%, (n=with/without)) | 23.6 (1734/5629)*123 | 18.3 (449/2006)*23 | 15.1 (220/1237) | 16.4 (209/1067) |

Data on some characteristics were missing in a few patients.

*1Significant difference between the figure in the column and that in JCS1.

*2Significant difference between the figure in the column and that in JCS2.

*3Significant difference between the figure in the column and that in JCS3.

CH, cerebral haemorrhage; JCS, Japan Coma Scale; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage.

We evaluated the consciousness levels in 13 406 out of 13 788 patients (97.2%), based on JCS. JCS data were missing for 382 patients (2.8%). Among the 13 406 patients, the number and percentage per group were as follows: JCS0 (7676 (55.7%)), JCS1 (2619 (9%)), JCS2 (1602 (11.6%)) and JCS3 (1509 (10.9%)), respectively. We evaluated the ADL scale in 12 601 (91.4%) patients at 30 days after the onset of neurological impairment. We obtained data on both JCS and the ADL scale in 12 277 (89%) of the stroke patients (table 2).

Table 2.

Numbers of patients categorised by JCS and by the ADL scale

| JCS0 | JCS1 | JCS2 | JCS3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL1 | 4621 | 608 | 199 | 65 | 5493 |

| ADL2 | 1908 | 816 | 365 | 104 | 3193 |

| ADL3 | 417 | 442 | 287 | 111 | 1257 |

| ADL4 | 146 | 276 | 325 | 296 | 1043 |

| ADL5 | 102 | 201 | 227 | 761 | 1291 |

| Total | 7194 | 2343 | 1403 | 1337 | 12277 |

We obtained data on both JCS and the ADL scale in 12 277 (89.0%) of the stroke patients.

ADL, activities of daily living; JCS, Japan Coma Scale.

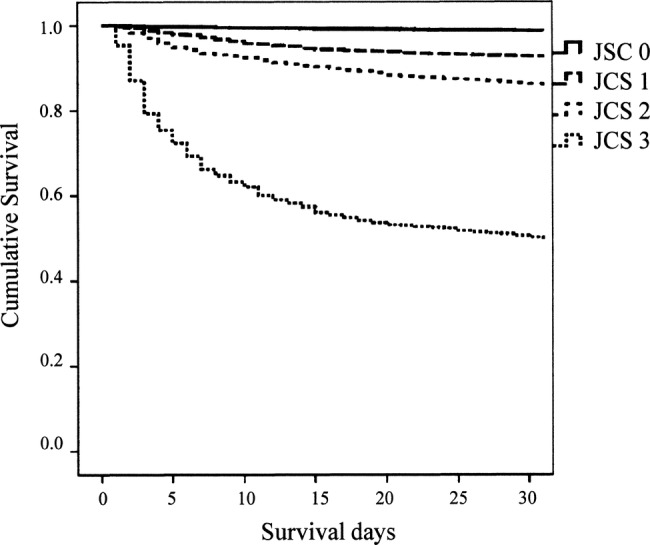

Spearman's correlation coefficient was 0.608 for the correlation between JCS and the ADL scale (p<0.001). The Kaplan-Meier Survival curves of patients in each JCS category are presented (figure 1). A log-rank test proved that the differences were significant (p<0.001). For the Kaplan-Meier Survival curves in each JCS category in each stroke subtype, see online supplementary figure S1A–C).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Survival curves for patients in each Japan Coma Scale category.

HRs for death, comparing JCS categories and their 95% CIs, are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

HRs for death, comparing JCS categories

| HR | 95% CI |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| JCS0 | Reference | |||

| JCS1 | 5.55 | 4.19 | 7.37 | <0.001 |

| JCS2 | 9.54 | 7.16 | 12.71 | <0.001 |

| JCS3 | 34.21 | 26.10 | 44.83 | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, sex, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, history (hypertension, arrhythmia and diabetes mellitus), stroke type and paresis.

JCS, Japan Coma Scale.

Discussion

Systems for describing patients with impaired consciousness were not consistent until 1974, when GCS and JCS were developed.7 There was an abundance of alternative terms by which levels of coma or impaired consciousness were described and recorded.7 Teasdale and Jennett7 mentioned that some might have reservations about a system which seemed to undervalue the niceties of a full neurological examination. Just as with GCS, it is no part of JCS to deny the value of a detailed appraisal of the patients as a whole, and of neurological function in particular.7

JCS principally focuses on eye responses. Being a single test, JCS has two outstanding merits as a coma scale, that is, simplicity and applicability, which should minimise interpreter errors. Simplicity is very important in communication among physicians, nurses and paramedics, especially in emergency settings. The present study adds to its virtues the predictability for early outcome in stroke patients.

In summary, the advantages of JCS include four points

Predictability for stroke outcome: This study showed the predictability of JCS for the stroke outcome. JCS correlated with the ADL scale. HRs for death were significantly different among JCS categories: 1.00 (as reference), 5.55, 9.54 and 34.21 in JCS0, JCS1, JCS2 and JCS3, respectively. It is noteworthy that a simple one-axis test alone predicts early mortality with such clear differences. JCS could be useful, especially in emergency settings when more detailed evaluation of a patient's condition is difficult to obtain and prompt communications among doctors and comedicals are needed. It provides minimum but critical/essential information.

Simplicity: JCS is a four-point scale (from 0 to 3) and comprises only one test: eye responses. GCS, for example, is a 13-point scale (from 3 to 15) and comprises three tests: eye, verbal and motor responses. JCS is similar to the eye response test in GCS but even simpler than the latter (ie, both E2 and E3 belong in JCS2). Being a unicoordinate axis scale is very important for simplicity. Although summing up scores in a multicoordinate axes scale may not be difficult, the scores in different axes may have different values, and therefore interpretation of a total score can be difficult. Hypothetically, both E3V2M1 and E2V3M1 in GCS, for example, give the same total score of 6. The same total score in a multicoordinate axes scale could reflect different underlying conditions and might be difficult to interpret. The description within JCS is also simpler (eg, JCS0, JCS1, JCS2 and JCS3), which makes communication among staff easy, prompt and less misleading. It might be easier to grasp the outline of a patient condition with JCS than with any multiaxes scale.

Reliability: The simplicity of JCS might provide consistency among raters. The four categories in JCS are well defined. They do not overlap and encompass all consciousness levels.

Applicability: JCS focuses on eye response, which broadens its applicability both for raters and for patients. Raters need only to check the eye responses in terms of three clearly differentiated categories: open, open only after stimuli and closed. No special knowledge, such as is needed to assess the decerebrate or decorticate response, is necessary. JCS is applicable to almost all patients, including patients with aphasia, paresis and even intubated patients, where it might be difficult to apply GCS, because it has verbal and motor responses tests. In this population-based study, JCS was applied to 13 406 of 13 788 stroke patients (97.2%).

There are some limitations. First, simplicity means lack of detail. JCS does not evaluate verbal or motor responses, which are tested in GCS. The total score in GCS ranges from 3 to15 and GCS can theoretically describe 120 (4 × 5 × 6) different conditions. The more tests a scale includes, the more details it can evaluate.12 13 However, as far as the HRs for early death and the ADL scores are concerned, JCS is sufficient as a predictor. A single-dimensional test is the best if the purpose of the test is fulfilled. If needed, we can describe a patient's condition in a detailed way: such as the decerebrate posture and decorticate posture. In JCS, three capital letters, R, I and A, are provided to describe restlessness, incontinence and apathy, respectively.

Second, consciousness levels may fluctuate even in the short period and scores may therefore be different from time to time. This difficulty is common to every coma scale, and the simplicity of JCS might minimise it. A multidimensional scale might be more difficult to evaluate.

Third, predictability of the outcome has inherent limitations.14 The outcomes, and therefore the HRs for death, depend not only on the baseline severity, but also on the treatment and patient conditions, including complications. This study did not include the treatments which must affect the outcomes. For precise evaluation of a relationship between two factors, it would be important to adjust for all the other factors. Treatment, for example, often varies from case to case. Adjustments for this are virtually impossible in a population-based study. Major treatments for stroke, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy or surgical intervention, however, should not have caused a major bias in this study, because the differences in HRs among the consciousness levels based on JCS remain significant after adjustment for stroke subtypes, that is, cerebral infarction, CH and SAH. JCS also predicted the outcome in each of the three subtypes of stroke by univariable analyses. tPA therapy is not applied for haemorrhagic stroke and surgical interventions are rarely applied for ischaemic stroke (in this study cohort, only 374 (4.2%) of 8896 cerebral infarction patients had surgical treatment).

There are two types of complications: ones that patients had before stroke onset and ones that they got after the onset. The former comprises numerous diseases, but risk factors such as hypertension, arrhythmia and diabetes mellitus might be important. The difference in HRs remained significant after adjustment for these three. The latter may include urinary tract infections, decubitus ulcers and pneumonia. They, however, occur as results of stroke, namely after the consciousness level estimation based on JCS. Although they could be related to the initial severity of the stroke, data on this type of complication were not available in this study.

Finally, we did not investigate the predictability of JCS in the light of the modern psychometric approach. Consciousness level is a latent trait and scales dedicated to its measurement should preferably undergo Rasch analysis to confirm or not their metric properties. Applying Rash analysis15–17 might give added values to the study since it might help to investigate some aspects of the measurement properties of JCS. The validity of the ADL scale has not yet been proved. Moreover, there is as yet no study about how consistently different assessors from different centres used the five-category scale. This ADL scale is based on how each patient performed ‘usual activities’, which may change from one patient to another according to their lifestyle and environment. The ADL Scale is widely used in Japan. It is also a simple scale which may have a practical value. We would like to study the validity, consistency among assessors and ways to elaborate the ADL scale.

Conclusions

The eye response test alone is sufficient to predict stroke outcome. Being a unicoordinate axis scale, JCS has two outstanding merits as a coma scale that is, simplicity and applicability. JCS's predictability of stroke outcome should help JCS attain international recognition as a standard coma scale.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of participating institutions and their staffs who provided data in the development of the Kyoto Stroke Registry. We thank Dr Tomio Ohta for the information on the establishment of JCS. We are grateful to many colleagues for their assistance in this study, particularly the late Dr Osamu Shimamura, Dr Tatsuyuki Sekimoto, Dr Kouichiro Shimizu, Dr Akihiko Nishizawa, Dr Atsushi Okumura, Dr Masahiro Makino and Dr Kazuhiko Bando. We would like to express special thanks to Dr Edith G. McGeer for her help on our manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed equally in the data collection. KS conceived the idea of the study and was responsible for undertaking data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. HN was a coinvestigator and Chair of the Kyoto Stroke Registry Committee (KSRC). YW was a coinvestigator and vice Chair of the KSRC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Board of Directors, the Kyoto Medical Association, the Department of Health and Welfare, Kyoto Prefecture and Ethics Committee of the National Hospital Organization, Minami Kyoto Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Annual reports of the Kyoto Stroke Registry are available at the Kyoto Medical Association.

References

- 1.Ohta T, Waga S, Handa W, et al. New grading of level of disordered consiousness (author's transl). No shinkei geka. Neurol Surg 1974;2:623–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohta T, Kikuchi H, Hashi K, et al. Nizofenone administration in the acute stage following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Results of a multi-center controlled double-blind clinical study. J Neurosurg 1986;64:420–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shigemori M, Abe T, Aruga T, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Head Injury, 2nd edition guidelines from the Guidelines Committee on the Management of Severe Head Injury, the Japan Society of Neurotraumatology. Neurol Med Chir 2012;52:1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohta T, Nishimura S. The research on prognosis prediction of surgical interventions for ruptured cerebral aneurysm—production of ABC index—the first report: the shortcomings of the conventional classification system of severity and determination of predicting factors of surgical prognosis. The First Meeting of Society on Surgery for Cerebral Stroke (In Japanese), Sakunami, Miyagi, Japan, 1972:1–20 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohta T, Waga S, Saito Y, et al. The survey on therapeutic strategy of cerebral aneurysm and prognosis after surgical interventions. The Second Meeting of Society on Surgery for Cerebral Stroke (In Japanese), Arima, Hyogo, Japan, 1973;2:55–75 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohta T, Waga S, Saito Y, et al. The new grading system for disturbed consciousness and its numerical expression; the 3-3-9 degrees method. The Third Meeting of Society on Surgery for Cerebral Stroke (In Japanese), Hakone, Kanagawa, Japan, 1974;3:61–8 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974;2:81–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir CJ, Bradford AP, Lees KR. The prognostic value of the components of the Glasgow Coma Scale following acute stroke. QJM 2003;96:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shigematsu K, Shimamura O, Nakano H, et al. Vomiting should be a prompt predictor of stroke outcome. Emerg Med J. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201586 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shigematsu K, Nakano H, Watanabe Y, et al. Characteristics, risk factors and mortality of stroke patients in Kyoto, Japan. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatano S. Experience from a multicentre stroke register: a preliminary report. Bull World Health Organ 1976;54:541–53 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingsma HF, Roozenbeek B, Steyerberg EW, et al. Early prognosis in traumatic brain injury: from prophecies to predictions. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:543–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA, Bamlet WR, et al. FOUR score and Glasgow Coma Scale in predicting outcome of comatose patients: a pooled analysis. Neurology 2011;77:84–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandra RV, Law CP, Yan B, et al. Glasgow coma scale does not predict outcome post-intra-arterial treatment for basilar artery thrombosis. Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:576–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggestrup LM, Hestbech MS, Siersma V, et al. Psychosocial consequences of allocation to lung cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnould C, Vandervelde L, Batcho CS, et al. Can manual ability be measured with a generic ABILHAND scale? A cross-sectional study conducted on six diagnostic groups. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friberg P, Hagquist C, Osika W. Self-perceived psychosomatic health in Swedish children, adolescents and young adults: an internet-based survey over time. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.