Abstract

Objectives

To prevent pain inhibiting their performance, many athletes ingest over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics before competing. We aimed at defining the use of analgesics and the relation between OTC analgesic use/dose and adverse events (AEs) during and after the race, a relation that has not been investigated to date.

Design

Prospective (non-interventional) cohort study, using an online questionnaire.

Setting

The Bonn marathon 2010.

Participants

3913 of 7048 participants in the Bonn marathon 2010 returned their questionnaires.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Intensity of analgesic consumption before sports; incidence of AEs in the cohort of analgesic users as compared to non-users.

Results

There was no significant difference between the premature race withdrawal rate in the analgesics cohort and the cohort who did not take analgesics (‘controls’). However, race withdrawal because of gastrointestinal AEs was significantly more frequent in the analgesics cohort than in the control. Conversely, withdrawal because of muscle cramps was rare, but it was significantly more frequent in controls. The analgesics cohort had an almost 5 times higher incidence of AEs (overall risk difference of 13%). This incidence increased significantly with increasing analgesic dose. Nine respondents reported temporary hospital admittance: three for temporary kidney failure (post-ibuprofen ingestion), four with bleeds (post-aspirin ingestion) and two cardiac infarctions (post-aspirin ingestion). None of the control reported hospital admittance.

Conclusions

The use of analgesics before participating in endurance sports may cause many potentially serious, unwanted AEs that increase with increasing analgesic dose. Analgesic use before endurance sports appears to pose an unrecognised medical problem as yet. If verifiable in other endurance sports, it requires the attention of physicians and regulatory authorities.

Keywords: Public Health, Sports Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

Participation in endurance sports, as in a marathon, is growing worldwide.

Many amateurs engage in occasional endurance activities without adequate training, medical information and experience.

They try to overcome pain during and after sports by taking over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics.

Key message

We hypothesised that the drugs taken before sports may increase the incidence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and kidney damage without lowering the pain during and after the exercise. An evaluation of about 4000 participants in a marathon and half marathon respectively supports this contention. Serious unwanted events occurred predominantly in users of analgesics. A benefit was not apparent.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first investigation which relates unwanted drug effects during endurance sports to the use of analgesics. The effect was significant in OTC doses and increased with higher doses. The incidence of organ damage was about five times more frequent after analgesic use. Serious events requiring hospital admittance were reported only in the analgesics group. These findings pinpoint the unexpected risk of the prophylactic use of these drugs in sports.

In our study, the role of confounders, as pre-existing joint pain, could not be excluded.

Introduction

Endurance sports are becoming increasingly popular. However, recent research has shown that physical activity does not automatically result in better health, but could exacerbate cardiovascular (CV) disease.1 2 This may be related to the inhibition of cyclooxygenases by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ‘over-the-counter’ (OTC) analgesics, that are known to exacerbate atherosclerosis3 and CV problems in some patients.4

Previous studies have shown that the use and abuse of analgesics in sports is frequent and possibly dangerous,5–11 and that the incidence and severity of electrolyte disturbances,12 13 gastrointestinal (GI)14 and renal adverse events (AEs)15–17 during and after racing double after taking analgesics. However, these studies investigated AEs in isolation and did not investigate a dose–response relationship.

In a preliminary study, we interviewed 1024 participants of the Bonn marathon/half marathon and collected information on their training, fitness and drug use.5 We found that over half of the participating athletes ingested analgesics before racing, most of them without medical advice.5 These results were confirmed by Gorski et al.18

We now report a follow-up study aiming at defining the use of analgesics in relation to premature race withdrawal and AEs occurring during and after racing. In this report, we summarise NSAIDs and other cyclooxygenase inhibitors including acetaminophen (paracetamol) as analgesics.

Methods

Study population

The investigation relied on a questionnaire made available to all participants of the Bonn marathon/half marathon 2010 on paper and via the internet by the organiser together with information on the purpose of the investigation. Participation in the study was recommended by the organiser (online supplementary figure S1). The questionnaire examined

Background epidemiology: age, sex, running experience, use of analgesics during training/in previous races and details of previous training.

Medication use before the race: name and dose of drugs taken before the race start and any medical advice received.

During and after racing: completion/reasons for premature withdrawal from the race and AEs.

Study design

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki on biomedical research involving human subjects (Somerset West amendment). Advertisement and study information was provided by the local organiser. All questionnaires returned were in an anonymised form which made identification of single participants impossible. The integrity of the participants remained unimpaired. After having consulted the local ethics committee, it was agreed that a formal application to the Institutional Ethics Review Board (IRB) was not required according to professional regulations. The scientific quality of the study design was not subjected to the control of the IRB.

The case reports (serious cases) were regarded as requests for medical advice and handled as such by MK (medical doctor) who preserved the anonymity of these ‘patients’.

All data sheets (received questionnaires) were checked for completeness and duplicates using SPSS software V.19, followed by inspection by two researchers.

Outcome measures

The primary hypothesis was that consumption of analgesics is associated with an increased incidence of AEs. An AE was included in the analysis if one or more of the following events were recorded on the questionnaire: GI cramps and bleeds, haematuria or CV events (eg, arrhythmia and palpitation).

Statistical analysis

AEs and reasons for premature race withdrawal were tabulated according to a number of population-based factors which may influence drug use or AE incidence. Cross-tables, the χ2 test or Fisher's test was used to analyse subgroups to establish relative risk differences and possible confounding factors. Drug doses (no drug, low dose and high dose) were used to determine possible dose-related effects on AE incidence and race withdrawal.

A binary regression model was used to estimate ORs and 95% CIs for AE incidence in subgroups and in the primary study population, with adjustment for confounding factors. Analyses were conducted using SPSS software V.19. Statistical tests were two-sided, and p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. AEs from respondents who did not state which race they entered were not included in the marathon/half-marathon subgroup analysis.

Results

A total of 4268 completed questionnaires were returned. More than 90% of the questionnaires were received by day 10, the rest within day 17 after the race. Approximately 4% were identified as duplicates and were excluded from the analysis (figure 1). An additional 4% of questionnaires were excluded because primary data were missing (ie, age, sex, drug use and AEs).

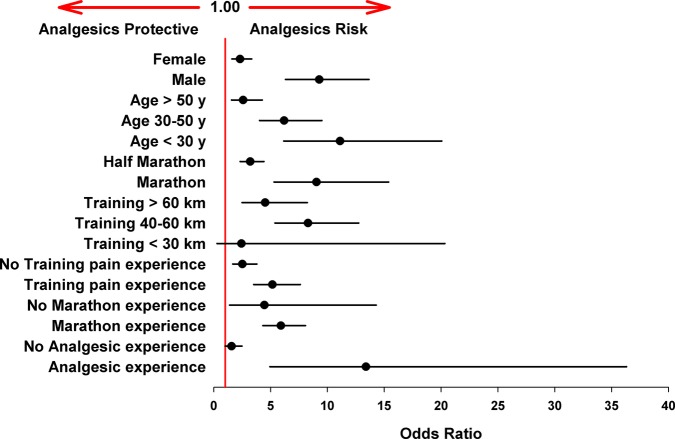

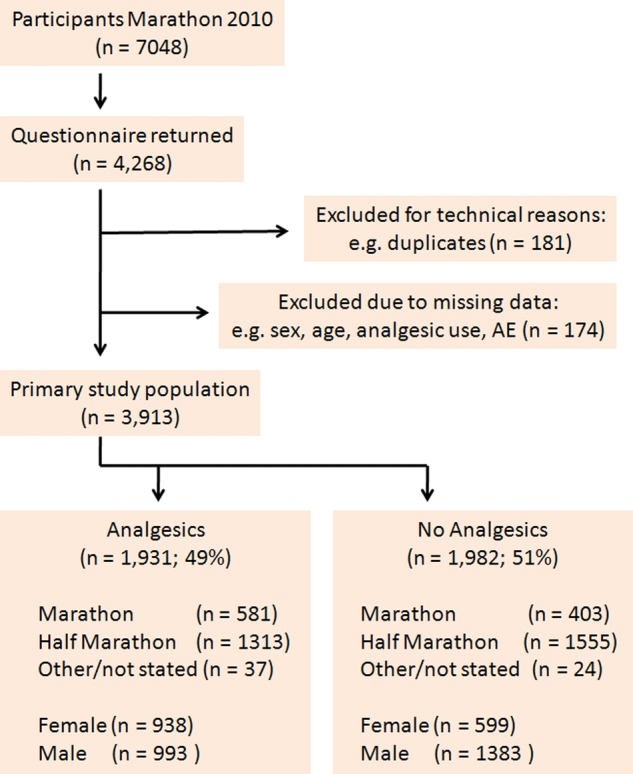

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the evaluation of the marathon/half-marathon running cohort. After the elimination of duplicates, almost 2000 questionnaires were returned from each cohort. The distribution of marathon and half-marathon runners was similar in each treatment cohort. If participants entered races other than the marathon or half marathon (eg, relays), or did not state which race they entered, they were captured in the ‘other/not stated’ cohort (AE, adverse event).

The remaining 3913 completed questionnaires constituted the primary study population, representing 56% of the participants in the Bonn marathon/half marathon 2010 (figure 1). Nearly half of the study cohort used analgesics before the actual race (‘analgesics cohort’: n=1931, 49%) and 51% reported not having used any analgesics (‘control group’: n=1982; figure 1).

Background epidemiology

Descriptive epidemiological data are given in online supplementary table S1. Overall, there were more men than women (2376 vs 1537), and the men were slightly older on average (means±SD: 40±10 vs 39±11 years). Men and women were younger in the control group (means±SD analgesic group: men 43±8, female 42±8 years vs control group: men 38±12, women 34±13 years). Most respondents had previous marathon experience (overall 87%). In the analgesics cohort, 20% had also taken analgesics during training (men 26% vs women 14%), compared with 1% of the control group. Of the analgesics cohort, 11% recorded pain before the race (compared with 1% of controls) and 16% recorded AEs during/after racing (compared with 2% of controls).

Medication use before racing

In total, 1931 respondents ingested analgesics before racing, to retard or avoid pain during the races and thereafter. They used analgesics immediately before the race. Most of the analgesics (54%) were taken without prescription (online supplementary table S2), and significantly more women (61%) took analgesics than men (42%).

The most frequently used analgesic was diclofenac, used by 47% of the analgesics cohort before the race (online supplementary table S2). Many athletes (11%) resorted to supra-OTC doses of diclofenac (over 100 mg). The second most commonly used analgesic was ibuprofen, and 43% of those who took ibuprofen ingested ≥800 mg (twice the recommended OTC single dose). Aspirin was used less frequently, mostly at low therapeutic doses. Acetaminophen, celecoxib, dipyrone, etoricoxib, meloxicam and naproxen were also used, although these drugs were taken by comparatively few athletes and are grouped as ‘other analgesics’ in the analysis (online supplementary table S2).

Of all respondents, 93% declared that they were not informed about the risks of using analgesics in connection with sports endurance (online supplementary table S1).

Events during and after the race

The incidence of reported AEs was significantly higher in runners of the full marathon compared with the half marathon (18% vs 7%; p<0.001). Additionally, the analgesic-related AE risk in the full marathon cohort was significantly higher than in the half-marathon cohort (OR 9.04; 95% CI 5.31 to 15.39 vs 3.20; 95% CI 2.32 to 4.42 (figure 2)).

Figure 2.

Risk of adverse events (AEs) within study subgroups (unadjusted). ORs were estimated by binary linear regression analysis. Almost all subgroups show enhanced risk for AEs after analgesic use (ORs >1; error bars represent 95% CI).

There were similar numbers of half-marathon and marathon runners in the analgesics cohort compared with controls.

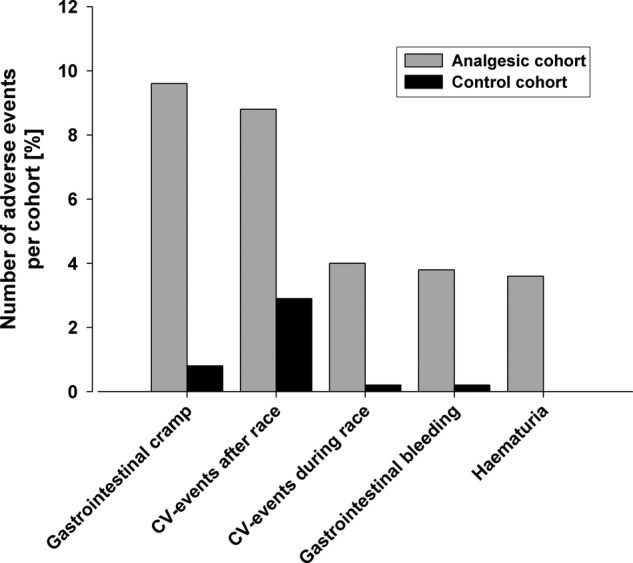

A 4–10 times higher incidence of each type of AE was observed in the analgesics cohort compared with controls (overall incidence 16% vs 4%, online supplementary table S3; figure 3), with a calculated risk difference of 13%. The difference in the incidence of AEs between the two cohorts was most prominent with respect to GI cramps and CV events (after the race). In the analgesics cohort, GI cramps were the most frequent AE (reported by 14% of the cohort), followed by CV AEs after the race (9%). In the controls, CV AEs after the race were the most frequently reported AE (3%, online supplementary table S3). Notably, haematuria was reported only in the analgesics cohort. The differences in the incidence of all AEs were highly significant between the two groups (p<0.001, online supplementary table S3; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Incidence of adverse events (AEs, derived from online supplementary table S3). Rounded percentages are given in online supplementary table S3. The differences between the groups were all highly significant; p<0.001.

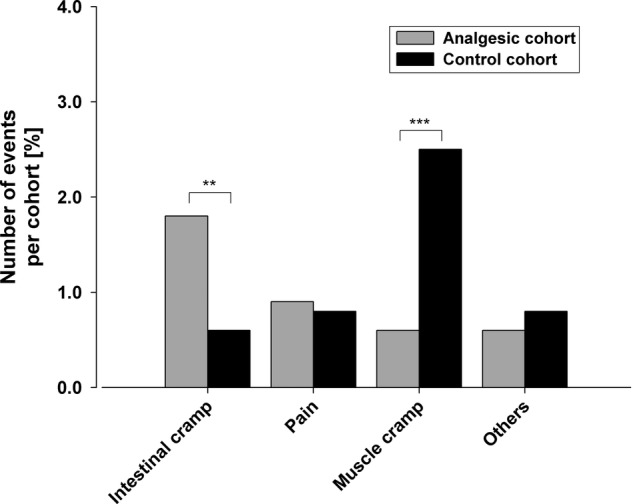

No significant difference was found between the analgesics cohort and controls in terms of premature race withdrawal overall (online supplementary table S3, p=0.237). Race withdrawal because of muscle cramps occurred significantly more often in controls (3% vs 1%, online supplementary table S3; figure 4, p<0.001), but the absolute difference was small. Conversely, intestinal cramps were significantly more frequently blamed for race withdrawal in the analgesics cohort compared with controls (2% vs 1%; p<0.01, online supplementary table S3; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reasons for premature termination of the race.

Rounded percentages are given in online supplementary table S3. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Note: the absolute numbers are small.

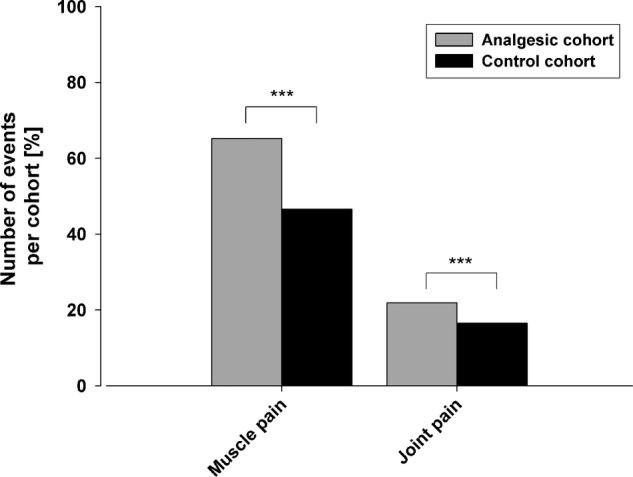

Joint and muscle pain after the race were significantly more frequent in the analgesics cohort than in controls (1301 vs 955 respondents, p<0.001, online supplementary table S3; figure 5).

Figure 5.

Percentage of runners experiencing muscle and/or joint pain after the race. Rounded percentages are given in online supplementary table S3. The differences are highly significant (***p<0.001).

The overall risk for analgesic-related AEs was estimated at 5.1 (95% CI 3.9 to 6.7; p<0.001, figure 6), giving a ‘number needed to harm’ of eight treated participants. In a subsequent subgroup analysis for sex, age, training, marathon/half-marathon run and analgesic experience, enhanced risk (OR) for the different subgroups was detected, but this was very variable (1.6–13.4, figure 2). Therefore, these subgroup parameters were included in a regression analysis which resulted in a comparable adjusted analgesic-related risk of 3.0 (95% CI 2.1 to 4.1; p<0.001, figure 6).

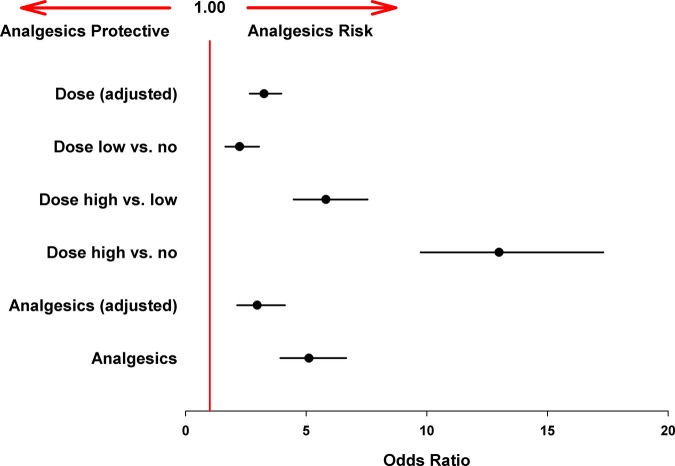

Figure 6.

Adjusted adverse event (AE) risks for analgesic use and dose dependency. There was a significant dose/AE relationship and reported ORs increased with increasing dose differences (dose no = controls without analgesic use). Adjusted ORs were estimated by binary linear regression using possible confounders (error bars represent 95% CI).

To investigate whether the incidence of AEs was dose-dependent, a risk estimation of the size of the dose was conducted. The high dose resulted in a significantly higher risk of AEs compared with the lower dose or controls. Even the low-dose group presented a higher risk of AEs compared with controls (figure 6). This further adjusted regression model showed a statistically significantly increased risk at rising doses, meaning that increasing the dose can increase the risk of AEs by three times (OR 3.2; 95% CI, 2.7 to 4.0, p<0.001, figure 6).

Finally, the association of analgesic use with distinct side-effect profiles was analysed. The ingestion of all three drugs used most frequently (aspirin, diclofenac and ibuprofen) was associated with AEs in a dose-dependent manner (table 1). Overall, the ‘drug-related’ incidence (defined as the percentage of respondents reporting AEs out of the total number of respondents taking a particular analgesic) was highest with aspirin, followed by ibuprofen, and lowest with diclofenac in both subgroups (high and low doses of analgesics, table 1). At high doses, 10% of diclofenac users, 52% of ibuprofen users and 87% of aspirin users experienced AEs (table 1). Aspirin was associated with relatively numerous GI or kidney bleeds, compared with the other analgesics (reported by 49% of the ‘high-dose’ aspirin users).

Table 1.

Incidence of adverse events (AEs) in relation to the analgesic used

| AEs | Diclofenac n=913 |

Ibuprofen n=722 |

Aspirin n=141 |

Other analgesics n=175 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low dose n=693 number of reports (%)* |

High dose n=220 number of reports (%) |

Low dose n=410 number of reports (%) |

High dose n=312 number of reports (%) |

Low dose n=102 number of reports (%) |

High dose n=39 number of reports (%) |

Low dose n=107 number of reports (%) |

High dose n=68 number of reports (%) |

|

| Urine blood | 6 (1) | 5 (2) | 5 (1) | 45 (14) | 7 (7) | 19 (49) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| GI-cramp | 16 (2) | 5 (2) | 52 (13) | 89 (29) | 11 (11) | 9 (23) | 4 (4) | 9 (13) |

| GI-bleeding | 2 (<1) | 8 (4) | 13 (3) | 39 (13) | 9 (9) | 19 (49) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| CV—during race | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 40 (10) | 28 (9) | 3 (3) | 8 (21) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| CV—post race | 4 (1) | 8 (4) | 44 (11) | 97 (31) | 11 (11) | 12 (31) | 3 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Total (individuals)† | 25 | 22 | 56 | 163 | 25 | 34 | 11 | 12 |

| Drug related AE incidence | 4% | 10% | 14% | 52% | 25% | 87% | 10% | 18% |

*Percentages relate to the corresponding subpopulations and are rounded to the nearest whole number.

†Number of individuals reporting AEs (a single individual may report >1 AE).

See online supplementary table S2 for definition of dose sizes.

CV, cardiovascular; GI, gastrointestinal.

Serious cases

In addition to the evaluation by questionnaire, the participants of the Bonn marathon/half marathon 2010 were encouraged to report serious events, which required hospital admittance during the 3 days following the race, to the physician in charge of this evaluation (MK). Nine case reports of hospital admittance were received (online supplementary table S4 by MK), all of which concerned participants of the analgesics cohort. Three athletes (numbers 1–3, online supplementary table S4) reported anuria/oliguria which started the day after the race and lasted for up to 3 days. In two cases, this AE resolved after a hyperuric period, and one respondent reported ongoing renal problems (haematuria for 2 days—number 3, online supplementary table 4). In all three cases, moderate doses of ibuprofen (2×400, 600 and 600 mg) were taken before and during the race together with large amounts of fluid.

Four respondents (numbers 4–7, online supplementary table S4) reported hospital admittance because of GI bleeding (black stools and vomiting blood). Gastroendoscopic evaluation revealed at least one intervention requiring bleeding ulcer. The patients were further monitored endoscopically and given proton pump inhibitors. All four respondents had ingested moderate amounts of aspirin (500–1000 mg) before the race, and all were released after a few days without obvious sequelae.

Two more respondents (numbers 8 and 9, online supplementary table S4) were hospitalised after ingesting aspirin before the race. One took a 100 mg dose to prevent infarction, whereas the other took 500 mg because of mild foot pain. Both respondents complained of chest pain, angina and arrhythmia on the day after the race, and both suffered cardiac infarctions. Both athletes recovered, although some cardiac damage remained in one respondent.

These nine cases are well documented (online supplementary table S4). However, it should be noted that since reporting was spontaneous and voluntary a lack of corresponding hospital admittance in the control cohort could not be proven. Also, we do not know whether the patients/participants filled and submitted an (anonymised) questionnaire.

Discussion

It is known that many professional and amateur athletes use analgesics prophylactically to increase performance and prevent pain.6–17 19 20

A recent publication in The New England Journal of Medicine12 warned that overhydration during marathons might increase the risk of CV events. However, this study did not investigate the association between the use of drugs and CV problems. Recently, we reported that two-thirds of the participants of a marathon took analgesics before the start.21 This investigation showed that most athletes taking analgesics had taken supratherapeutic doses. Similar data were reported by Gorski et al.18 However, these studies did not investigate the use of analgesics and premature race withdrawal, and nor did they systematically record the performance and incidence of AEs.

The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that cyclooxygenase inhibitors contribute to the development of AEs, which is possible as these drugs block the protective effects of prostaglandins on GI, CV and renal function. We hypothesise that their use is likely to suspend the mucosa-protective and kidney-protective3 effects of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)/prostacyclin (PGI2), thus augmenting the damaging effect of diminished blood flow22 and oxygen supply for the GI mucosa and kidney.23 Moreover, it was postulated that marathon runs could decrease the barrier function of the intestinal mucosa, further increasing the absorption of bacterial toxins from the gut,24 and that repeated inhibition of the production of endothelium-produced PGI2 during CV stress, for example, intensive exercise, may accelerate atherosclerosis.1 2 25

This study analysed respondents for age, sex, training status, drug use (including doses), race completion and AEs that occurred during the race and afterwards. To the best of our knowledge, this study shows for the first time that the administration of analgesics before a marathon/half marathon can significantly increase AEs, and these increase with increasing analgesic dose. This increased incidence of AEs is dramatic; for example, 4% of respondents in the analgesics cohort reported haematuria compared with 0% of controls. Moreover, nine respondents reported hospital admittance caused by either temporary kidney failure, bleeding ulcers or cardiac infarctions. All these serious events occurred in the analgesics cohort.

Altogether, these data do not support the contention that taking analgesics before a race improves the ability to complete the race or to prevent AEs thereafter.

Four aspects of this study deserve an in-depth discussion.

Analgesics taken prophylactically before racing do not prevent pain

Analysis of the pain reported by respondents before and after racing showed no major identifiable advantages gained from taking analgesics. Muscle cramps were reported as a reason for premature race withdrawal marginally less frequently in the analgesics cohort compared with the control. Although the difference was significant (p<0.001), the small sample size does not allow concrete conclusions to be drawn, particularly in the context of the parameters of overall pain during the race and intestinal cramps. There were significantly more intestinal cramps in the analgesics cohort (p<0.001) compared with the control, and more muscle and joint pains were reported in the analgesics cohort after the race than in the control.

This result supports observations reported by Nieman et al,26 who found that the intake of ibuprofen at regular intervals during an ultramarathon race did not decrease muscle soreness in the days afterwards. This may be explained by the fact that all the drugs investigated (diclofenac, ibuprofen and aspirin) display a short elimination half life of around 2 h, which would make effects several hours after the ingestion of the drugs rather unlikely. In the report by Nieman et al, the last dose of ibuprofen was taken several hours before finishing the race, and so the lack of influence on postrace pain is not surprising. Several research groups have reported the analgesic effects of NSAIDs in volunteers undertaking physical exercise. However, in these studies, the drugs were given after the exercise, not before, which makes their reported analgesic effect plausible and recognisable.27–29

In conclusion, our data indicate that the intake of cyclooxygenase inhibitor analgesics does not offer protection from pain during or after a marathon/half marathon compared with controls. However, definitive proof of this contention would warrant a prospective, randomised cohort study.

Analgesics contribute to AEs

This study investigated if cyclooxygenase inhibitors contribute to the AEs observed frequently in endurance sports.24 30 All of the AEs observed frequently during marathons, that is, CV events, GI cramps/bleeds and renal dysfunction, occurred much more frequently in the analgesics cohort compared with the control. This effect was not dependent on the type of analgesic, that is, all three drugs used frequently caused an increase in CV, GI and renal AEs. This supports our hypothesis that the use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors before the start of a race may be damaging because tissue protection that is usually provided by prostaglandins may be impaired, triggering GI, CV and renal AEs. These effects again suggest that the use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors before and during a marathon/half-marathon race may be dangerous and should be avoided.

The AE profile of different analgesics is different

Although the use of analgesics increases the overall incidence of AEs, all of the nine serious events reported to us, which led to temporary hospital admittance, concur with the pattern of AEs seen per drug in the rest of the respondents. The three temporary kidney failure cases (all of whom had ingested ibuprofen) correspond with the relatively high incidence of renal AEs in the ibuprofen group (table 1). Moreover, the bleeding ulcers observed in the aspirin group mirror the high incidence of GI problems seen after the intake of aspirin. Somewhat surprising is the fact that both cardiac infarctions occurred in the aspirin group. This is interesting as aspirin should have protected from such events. However, definite conclusions cannot be drawn because of the small sample size. Overall, our observations are in line with previous reports.1 31–33

Limitations of the study

A double-blind, randomised, crossover design for any trial is the gold standard. However, this is obviously impractical in these circumstances. Despite the relatively high return of questionnaires, there was still no information available for half of the marathon/half-marathon participants, and many confounding factors such as body mass index, use of other drugs, etc, were not investigated. Implementing a higher number of items in our questionnaire in order to cover additional confounders will have limited participant compliance and affect the overall response rate. Although the two cohorts were of similar size, there are differences between them with respect to age, sex, training and drug experience (a contribution of long-term use of OTC analgesics on the incidence of AEs cannot be excluded), which may also have influenced the outcome. However, the considerable homogeneity of the AEs seen throughout all subgroups supports the overall contention that cyclooxygenase inhibitors taken before and during a marathon/half-marathon race increase the risks of AEs substantially, without measurable benefit in terms of race completion.

Taken together, our data indicate that the widespread use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors in connection with endurance sports is potentially damaging. In our study, the administration of analgesics before the start of a race did not prevent postexercise pain or significantly reduce the premature withdrawal rate compared with the control. Conversely, the use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors considerably increased the incidence of GI, renal and CV AEs. We conclude that the use of analgesics before and during endurance sports may pose a serious health problem that should be addressed. Our investigation has also shown a worrying lack of education about these AEs within the participants of the Bonn 2010 marathon/half marathon, which may highlight a larger problem if mirrored in the endurance sport community in general. We would encourage greater awareness of the possible AEs of these drugs, particularly among endurance sports enthusiasts.

Further investigations are warranted to examine whether the use of analgesics before and during sports activities should be avoided altogether.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of a medical writer in the editing and language checking of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MK and BR contributed equally to this work. MK and KB conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the study design. MK was solely responsible for the case report data. Data acquisition, management and quality control were performed by BR, PO, UN and MK. BR was responsible for the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. MK, BR, PO and KB contributed to the interpretation of the results. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by KB and UN. All authors revised successive drafts of the manuscript critically and approved the final version to be published.

Funding: The Hertie Foundation supported KB by giving a grant for office requisites.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Schwartz JG, Merkel-Kraus S, Duval S, et al. Does longterm endurance running enhance or inhibit coronary artery plaque formation? A prospective multidetector CTA study of men completing marathons for least 25 consecutive years. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:A.173.E1624 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Breuckmann F, et al. Running: the risk of coronary events : prevalence and prognostic relevance of coronary atherosclerosis in marathon runners. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1903–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31:986–1000|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon CP, Curtis SP, FitzGerald GA, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) programme: a randomised comparison. Lancet 2006;368:1771–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brune K, Niederweis U, Krämer B. Sport und Schmerzmittel: Unheilige Allianz zum Schaden der Niere. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2008;105:1894–900 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tscholl P, Alonso JM, Dolle G, et al. The use of drugs and nutritional supplements in top-level track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:133–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tscholl P, Feddermann N, Junge A, et al. The use and abuse of painkillers in international soccer: data from 6 FIFA tournaments for female and youth players. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:260–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tscholl PM, Dvorak J. Abuse of medication during international football competition in 2010—lesson not learned. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:1140–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taioli E. Use of permitted drugs in Italian professional soccer players. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:439–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Heliovaara M, et al. Ample use of physician-prescribed medications in Finnish elite athletes. Int J Sports Med 2006;27:919–25|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Da Silva ER, De Rose EH, Ribeiro JP, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory use in the XV Pan-American Games (2007). Br J Sports Med 2011;45:91–4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almond CS, Shin AY, Fortescue EB, et al. Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1550–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wharam PC, Speedy DB, Noakes TD, et al. NSAID use increases the risk of developing hyponatremia during an Ironman triathlon. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:618–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halvorsen FA, Lyng J, Ritland S. Gastrointestinal bleeding in marathon runners. Scand J Gastroenterol 1986;21:493–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Meur Y, Paraf F, Szelag JC, et al. Acute renal failure in a marathon runner: role of glomerular bleeding in tubular injury. Am J Med 1998;105:251–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irving RA, Noakes TD, Raine RI, et al. Transient oliguria with renal tubular dysfunction after a 90 km running race. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1990;22:756–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulter J, Noakes TD, Hew-Butler T. Acute renal failure in four Comrades Marathon runners ingesting the same electrolyte supplement: coincidence or causation? S Afr Med J 2011;101:876–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorski T, Cadore EL, Pinto SS, et al. Use of NSAIDs in triathletes: prevalence, level of awareness and reasons for use. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahler N. Misuse of drugs in recreational sports. Ther Umsch 2001;58:226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippi G, Franchini M, Guidi GC, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in athletes. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:661–2; discussion 62–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brune K, Niederweis U, Kaufmann A, et al. Drug use in participants of the Bonn Marthon 2009. MMW Fortschr Med 2009;151:39–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kehl O, Jager K, Munch R, et al. Mesenterial anemia as a cause of jogging anemia?. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1986;116:974–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noakes TD, Sharwood K, Speedy D, et al. Three independent biological mechanisms cause exercise-associated hyponatremia: evidence from 2,135 weighed competitive athletic performances. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:18550–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pals KL, Chang RT, Ryan AJ, et al. Effect of running intensity on intestinal permeability. J Appl Physiol 1997;82:571–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott PA, Kingsley GH, Scott DL. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiac failure: meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised controlled trials. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:1102–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Dumke CL, et al. Ibuprofen use, endotoxemia, inflammation, and plasma cytokines during ultramarathon competition. Brain Behav Immun 2006;20:578–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tokmakidis SP, Kokkinidis EA, Smilios I, et al. The effects of ibuprofen on delayed muscle soreness and muscular performance after eccentric exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17:53–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasson SM, Daniels JC, Divine JG, et al. Effect of ibuprofen use on muscle soreness, damage, and performance: a preliminary investigation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25:9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donnelly AE, McCormick K, Maughan RJ, et al. Effects of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug on delayed onset muscle soreness and indices of damage. Br J Sports Med 1988;22:35–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert GP, Boylan M, Laventure JP, et al. Effect of aspirin and ibuprofen on GI permeability during exercise. Int J Sports Med 2007;28:722–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson JD, Maughan RJ, Davidson RJ. Faecal blood loss in response to exercise. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:303–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons SM, Kennedy RG. Gastrointestinal problems in runners. Curr Sports Med Rep 2004;3:112–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page AJ, Reid SA, Speedy DB, et al. Exercise-associated hyponatremia, renal function, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use in an ultraendurance mountain run. Clin J Sport Med 2007;17:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.