Abstract

Objectives

To compare real-world outcomes of initiating insulin glargine (GLA) versus neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin among employees with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who had both employer-sponsored health insurance and short-tem-disability coverages.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters/Health and Productivity Management Databases 2003–2009.

Participants

Adult employees with T2DM who were previously treated with oral antidiabetic drugs and/or glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonists and initiated GLA or NPH were included if they were continuously enrolled in healthcare and short-term-disability coverages for 3 months before (baseline) and 1 year after (follow-up) initiation. Treatment selection bias was addressed by 2:1 propensity score matching. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using different matching ratios.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Outcomes during 1-year follow-up were measured and compared: insulin treatment persistence and adherence; hypoglycaemia rates and daily average consumption of insulin; total and diabetes-specific healthcare resource utilisation and costs and loss in productivity, as measured by short-term disability, and the associated costs.

Results

A total of 534 patients were matched and analysed (GLA: 356; NPH 178) with no significant differences in baseline characteristics. GLA patients were more persistent and adherent (both p<0.05), had lower rates of hospitalisation (23% vs 31.4%; p=0.036) and endocrinologist visits (19.1% vs 26.9%; p=0.038), similar hypoglycaemia rates (both 4.4%; p=1.0), higher diabetes drug costs ($2031 vs $1522; p<0.001), but similar total healthcare costs ($14 550 vs $16 093; p=0.448) and total diabetes-related healthcare costs ($4686 vs $5604; p=0.416). Short-term disability days and costs were numerically lower in the GLA cohort (16.0 vs 24.5 days; p=0.086 and $2824 vs $4363; p=0.081, respectively). Sensitivity analyses yielded similar findings.

Conclusions

Insulin GLA results in better persistence and adherence, compared with NPH insulin, with no overall cost disadvantages. Better persistence and adherence may lead to long-term health benefits for employees with T2DM.

Keywords: healthcare utilization, employee productivity, diabetes costs

Article summary.

Aritcle focus

Do differences seen in the outcomes of randomised controlled trials comparing insulin glargine and neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) translate to improved real-world outcomes in employed adults living in the USA?

Key messages

Insulin glargine was associated with better persistence, lower inpatient admission, which offsets its higher drug cost, and lower indirect costs from short-term disability than NPH insulin.

Reduced short-term disability and improved adherence with insulin glargine may improve long-term productivity, compared with NPH insulin, and provide benefits to both employees and their employers.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The MarketScan database represents a large and diverse data source.

The database captures detailed information on both employees’ healthcare resource utilisation and their productivity, as measured by short-term-disability.

The use of propensity-score-matching methodology reduces treatment selection bias between the insulin glargine and NPH groups.

Sensitivity analysis confirmed the consistency of the findings.

As with all retrospective studies, causality of treatment effects cannot be established in this study. This study used a convenience sample, so it is not representative of the overall US population, and also may be underpowered to detect all significant differences between groups.

Confounding by indication or prognosis may be sources of bias in this restrospective observational study.

It is unlikely that rates of hypoglycaemia and other clinical outcomes would be captured with the same level of sensitivity in this retrospective analysis as they would in a randomised clinical trial. Further, glycated haemoglobin data were not available, and therefore neither the effectiveness of glycaemic control nor its association with hypoglycaemia could be assessed.

Introduction

In the USA, diabetes affects an estimated 25.8 million people (8.3% of the US population).1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and associated comorbidities are associated with disability, reduced productivity and work loss,2 3 which impose an important economic burden on self-insured employers.4 The diabetes-related economic burden from lost productivity and disability for employees and employers is substantial. Overall, reduced national productivity related to diabetes accounted for $58 billion in 2007 in the USA,5 while in a more recent study diabetes accounted for 1 473 000 disability-adjusted life years.6

Early improvements in glucose control can reduce the long-term risk of complications associated with T2DM.7 Adherence to antihyperglycaemic interventions is also associated with improved glycaemic control and decreased healthcare resource utilisation8 and consequently may improve outcomes. Adherence to medication also reduces the incidence of complications, and is thus associated with improved work-related outcomes, such as reducing the number of short-term disability days.9 Moreover, although adherence is associated with higher drug costs, overall healthcare costs decrease in adherent patients with diabetes and other chronic conditions.10 11 People with untreated diabetes, or those with a long duration of the disease, are at increased risk of occupational injury, which is minimised in treated patients who are adherent to medication.12 Effective pharmacological management of diabetes with adequate compliance also results in substantial cost benefits to employers.10 13

A regimen of oral glucose-lowering drugs combined with basal insulin analogues provides clinically relevant improvements in glycaemic control with a good safety profile.14 Options for basal insulin include insulin glargine, a long-acting basal insulin analogue, or neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, an intermediate-acting insulin. Clinical studies have shown that the efficacy of these two agents is similar, but that there is a lower risk of hypoglycaemia, particularly nocturnal hypoglycaemia, with insulin glargine.15–17

Simplicity and convenience of treatment regimens are important for those initiating insulin therapy. Insulin glargine was approved for once-daily injection and may have implications for increased patient persistence and adherence.18 However, twice-daily use of insulin glargine might be required to achieve therapeutic goals in some patients with T2DM.19 Other insulin therapy options, such as insulin detemir and insulin lispro protamine suspension, also have convenience and outcome benefits which may contribute to improved persistence and adherence.20–22 In reality, patients taking insulin glargine have been shown to be more likely to persist with their medication than those taking NPH insulin.23 In general, treatment complexity for chronic conditions—including, though not limited to the need to administer more than one injection daily—correlates with poor adherence.24

Although there are data in support of the clinical benefits of basal insulins, there is currently a paucity of real-world information about the impact of different basal insulin regimens on healthcare utilisation, employee disability and their associated costs from an employer's perspective. This analysis was performed in order to compare real-world outcomes from initiating insulin glargine or NPH insulin among employees with T2DM who had both employer-sponsored health insurance and short-tem-disability coverages. As insulin detemir, another long-acting basal insulin analogue, was only launched in the USA in 2006, too few patients were being treated with this agent for it to be included in the analysis as a comparator.

Methods

Database

This study is a retrospective analysis from the employer perspective of patients’ medical and pharmacy claims extracted from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database 2003–2009. This database captures person-specific clinical utilisation, expenditures and enrolment across inpatient, outpatient, prescription drug and carve-out services from about 100 large employers, health plans and government and public organisations.

Short-term disability data were extracted from the MarketScan Health and Productivity Management Database, which is an integrated database that contains information on absence, short-term disability and workers’ compensation experience. This information is linkable to the medical, pharmacy and enrolment data in the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database for these employees, providing a unique and valuable resource for examining health and productivity issues for an employed, privately insured population.

The MarketScan Research Databases are fully compliant with the letter and spirit of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and the Institutional Review Board review was waived.

Cohort selection criteria

Included in the analysis were employees, but not their dependants, aged 18 years or older with T2DM, defined as having made at least one inpatient visit or two physician visits dated at least 30 days apart, with a primary or secondary diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type II or unspecified type not stated as uncontrolled (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 250.x0) or T2DM or unspecified type uncontrolled (code 250.x2); at least one pharmacy claim of insulin glargine or NPH insulin with the date of the first such claim being the index date (prescriptions of other basal insulins were too low for inclusion); enrolled for medical and pharmacy healthcare benefits and work benefits for short-term disability for 3 months prior to insulin initiation (baseline period) and 12 months after insulin initiation (follow-up period); and on at least one oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) or exenatide, but no insulin, during the baseline period. The patient cohorts for comparison were determined on the basis of use of insulin glargine or NPH insulin at initiation of insulin therapy. Patients initiating insulin detemir were excluded from the current study because it was available only after 2006, and thus an insufficient number of patients (fewer than 100) were identified in the database to provide adequate statistical power for meaningful comparisons. Outcomes were compared between the matched cohorts after 1 year of follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

Data were analysed to assess baseline characteristics, including: gender, age, OAD use, comorbidities, healthcare utilisation/costs, index drug copay and short-term disability for 3 months prior to insulin initiation for all patients. Follow-up records were analysed to assess treatment persistence, adherence, hypoglycaemic events, healthcare resource utilisation, cost and short-term disability after initiation of insulin therapy.

Persistence and adherence

Measuring persistence with insulin treatment is challenging due to its non-fixed dose schedule. Consistent with previously published studies,25–27 persistence was measured here as the time the patient had remained on the study drug without discontinuation or switching following insulin initiation. Study medication was considered to be discontinued if the prescription was not refilled within the expected time of medication coverage, defined as the 90th percentile of the time, stratified by the metric quantity supplied, between the first and second fills among patients with at least one refill. For example, our analysis showed that for patients who filled a prescription for 10 ml and refilled later, 90% of insulin glargine patients refilled it within 119 vs 113 days for NPH patients. Subsequently, a patient was considered to have discontinued insulin glargine if he/she previously filled a prescription for 10 ml of insulin glargine but did not refill it within 119 days. Patients who restarted their initial medication after discontinuation, as defined above, were also considered non-persistent patients. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted using the 75th and 95th percentiles of the time.

Treatment adherence was measured during the 1-year follow-up by both the traditional medication possession ratio (MPR) and the adjusted MPR, which allows for differences in the insulin-device package size28 (insulin glargine, eg, is packaged either in 10 ml vials with a total of 1000 units or in a 3 ml disposable device in a package of 5 pens with a total of 1500 units) to correct the issue that almost all prescriptions are dispensed with a 30-day supply documented by the pharmacy. The adjusted MPR was calculated by multiplying the traditional MPR (the total days’ supply of all filled insulin glargine or NPH prescriptions in the analysis period divided by the number of days in the analysis period) by the average number of days between insulin study drug prescription refills for patients using the insulin divided by the average days’ supply for patients using the insulin. By using data based on the actual gap between the days’ supply and the days to next refill, this adjustment is necessary to measure real adherence to the doctor's instructions.

Clinical outcomes

Hypoglycaemia was defined as a healthcare encounter (outpatient, inpatient or emergency department visit) with a primary or secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for hypoglycaemia (ICD-9 code 250.8—diabetes with other specified manifestations; 251.0—hypoglycaemic coma; 251.1—other specified hypoglycaemia or 251.2—hypoglycaemia, unspecified).29 Daily average consumption (DACON) of insulin was estimated based on pharmacy claims data and calculated as the total number of units dispensed before the last refill of the study drug divided by the total number of days between initiation and last refill during the follow-up period. Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) data were not available in this study.

Healthcare resource utilisation and cost

Categories of healthcare resource utilisation included the number of outpatient visits, emergency room (ER) visits, inpatient admissions, inpatient length of stay (days) and total outpatient pharmacy claims (average outpatient claims). Diabetes-specific healthcare resource utilisation included claims with a primary diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9-CM: 250.xx) and the use of antihyperglycaemic medications, glucose meters and supplies.

Healthcare costs were computed as paid amounts of adjudicated claims, including insurer and health-plan payments, copayments and deductibles. Diabetes-specific healthcare costs included those related to a primary or secondary diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9-CM: 250.xx).

Loss in productivity and its associated costs

Loss in productivity was measured by the total number of days patients were on short-term disability during the baseline and follow-up periods. The associated costs for short-term disability were calculated as 70% of $240 (a figure reflecting the average daily wage paid to employees of large employers),30 which amounts to $168, since disability programmes typically pay for 70% of lost income.31

Total cost

Total cost was assessed by combining direct costs (healthcare costs) and indirect costs (short-term disability costs), and comparisons between groups were made. Costs were adjusted for inflation to 2010 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analyses

To reduce the observed baseline selection bias between the two study cohorts, propensity score matching (PSM) methodology32 was implemented, with a stringent 2:1 matching of patients initiating insulin glargine or NPH insulin. Propensity scores for initiating insulin glargine versus NPH were calculated from a logistic regression model that estimated the likelihood of initiating insulin glargine based on the observed patient characteristics. Covariates were selected based on their hypothesised confounding relationship with the outcome variables, and included age, gender, region, health plan type, Charlson Comorbidity Index and baseline concomitant medications, hypoglycaemic events, healthcare utilisation (overall or disease-related), copays and healthcare cost (overall or disease-related). Sensitivity analyses were also conducted using 1:1 and 3:1 PSM.

Among the matched cohorts, all study variables, including baseline and outcome measures, were analysed descriptively. Results were stratified by treatment cohort. For dichotomous variables, p values were calculated according to the Mann-Whitney U test; for continuous variables, t tests were used to calculate p values. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test were used to compare 1-year treatment persistence. Relationships between treatment persistence and hospitalisation as well as short-term disability were investigated by the χ2 test. p Values of <0.05 were taken to be indicative of a significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Data from 2454 patient records were eligible for the 1-year follow-up analyses: 2250 in the insulin glargine cohort, and 204 in the NPH insulin cohort. Before the matching, patients using insulin glargine were more likely to be male, older, using the insulin pen and having a higher copayment than those using NPH (data not shown). The 2:1 PSM yielded a total of 534 patients (insulin glargine, n=356; NPH insulin, n=178) with well-matched baseline characteristics (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (3 months prior to index)

| Insulin glargine (n=356) | NPH insulin (n=178) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, female (%) | 153 (42.9) | 81 (45.5) | 0.5789 |

| Age, years, mean±SD | 49±10 | 49±10 | 0.7580 |

| Health plan, n (%) | 0.9390 | ||

| CDHP | 5 (1.4) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Comprehensive | 34 (9.5) | 18 (10.1) | |

| HMO | 63 (17.6) | 36 (20.2) | |

| POS | 65 (18.2) | 29 (16.2) | |

| PPO | 189 (53.0) | 93 (52.2) | |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| North central region | 82 (23.0) | 45 (25.2) | 0.5653 |

| Northeast region | 58 (16.2) | 32 (17.9) | 0.6238 |

| South region | 129 (36.2) | 54 (30.3) | 0.1758 |

| West region | 85 (23.8) | 45 (25.2) | 0.7215 |

| Unknown | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 0.4778 |

| Pen use for initiated insulin, n (%) | 59 (16.5) | 33 (18.5) | 0.5706 |

| Antidiabetic drugs, n (%) | |||

| Metformin | 262 (73.5) | 132 (74.1) | 0.8893 |

| Sulfonylureas | 223 (62.6) | 105 (58.9) | 0.4138 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 133 (37.3) | 68 (38.2) | 0.8497 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 9 (2.5) | 6 (3.3) | 0.5785 |

| Exenatide | 30 (8.4) | 11 (6.1) | 0.3579 |

| Number of OADs, mean±SD | 1.81±0.73 | 1.80±0.75 | 0.9015 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean±SD | 0.284±0.819 | 0.281±1.159 | 0.9770 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 76 (21.3) | 39 (21.9) | 0.8817 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 39 (10.9) | 22 (12.3) | 0.6305 |

| Retinopathy | 7 (1.9) | 5 (2.8) | 0.5357 |

| Neuropathy | 19 (5.3) | 8 (4.4) | 0.6752 |

| Nephropathy | 15 (4.2) | 3 (1.6) | 0.1270 |

| Healthcare utilisation, n (%) or mean±SD (median) | |||

| All-cause hospitalisations | 53 (14.8) | 28 (15.7) | 0.7980 |

| All-cause total hospitalisation days | 0.97±3.38 (0) | 0.72±2.11 (0) | 0.3018 |

| All-cause ER visits | 80 (22.4%) | 38 (21.3%) | 0.7680 |

| Endocrinologist visits | 38 (10.6%) | 25 (14.0%) | 0.2550 |

| Diabetes-related hospitalisations | 34 (9.5%) | 20 (11.2%) | 0.5426 |

| Diabetes-related total hospitalisation days | 0.52±2.31 (0) | 0.41±1.49 (0) | 0.4975 |

| Diabetes-related ER visits | 37 (10.3) | 17 (9.5) | 0.7608 |

| Any hypoglycaemia visit, n (%) | 15 (4.2) | 6 (3.4) | 0.9197 |

| Total healthcare cost, mean±SD (median) | |||

| Inpatient cost | 2756±12393 (0) | 1958±8241 (0) | 0.3766 |

| Outpatient cost | 1385±3652 (498) | 1766±4243 (613) | 0.3068 |

| ER cost | 181±476 (0) | 144±515 (0) | 0.4138 |

| Prescription cost | 937±1236 (677) | 926±1065 (699) | 0.9117 |

| Total cost | 5259±14237 (1632) | 4794±10731 (1895) | 0.6735 |

| Total diabetes-related healthcare cost, mean±SD (median) | |||

| Inpatient cost | 1304±6588 (0) | 811±3447 (0) | 0.2570 |

| Outpatient cost | 242±321 (158) | 274±505 (131) | 0.4393 |

| ER cost | 46±216 (0) | 34±195 (0) | 0.5346 |

| Prescription cost | 294±293 (204) | 285±309 (154) | 0.7474 |

| Diabetes supply cost | 48±97 (0) | 46±92 (0) | 0.7766 |

| Total cost | 1934±6551 (621) | 1450±3485 (596) | 0.2658 |

| Copay of index drug, n (%) | 0.8694 | ||

| $0–$15 | 166 (46.6%) | 87 (48.8%) | |

| $15–$30 | 147 (41.2%) | 71 (39.8%) | |

| $30+ | 42 (11.7%) | 20 (11.2%) | |

| Short-term disability, mean±SD | |||

| Occurrence count | 0.12±0.34 | 0.12±0.37 | 0.9310 |

| Days | 3.10±12.97 | 2.98±12.9 | 0.9153 |

| Cost | 538±2250 | 534±2349 | 0.9856 |

| Total cost (healthcare+short-term disability), mean±SD | 5797±15005 | 5328±12174 | 0.6987 |

Baseline information is collected within 3 months prior to the index date.

CDHP, consumer-driven health plan; CHF, congestive heart failure; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; ER, emergency room; HMO, health maintenance organisation; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin; OADs, oral antidiabetic drugs; POS, point of service; PPO, preferred provider organisation.

Persistence and adherence

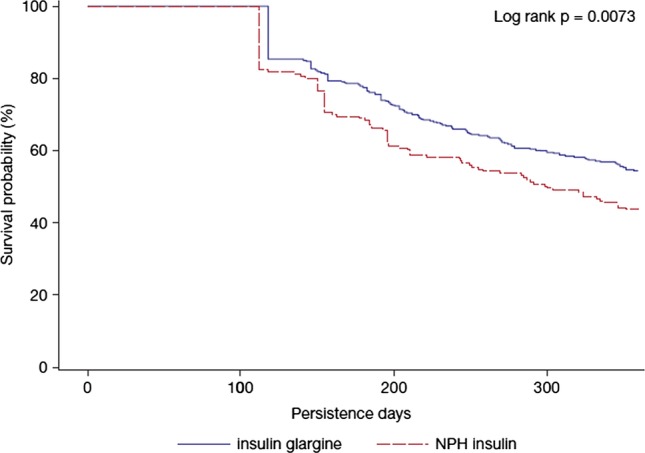

During the 1-year follow-up, patients receiving insulin glargine were significantly more persistent (table 2) with and adherent to study medication compared with those in the NPH insulin cohort (table 2). Patients stayed on insulin glargine treatment for a significantly longer period (approximately 22 days longer) than those on NPH insulin. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows that patients treated with NPH insulin discontinued sooner than those treated with insulin glargine (log-rank test p=0.0073; figure 1). Sensitivity analyses using the 75th and 95th percentiles yielded similar results (75th percentile: 34% vs 28.1%, p=0.17; 95th percentile: 67.2% vs 57.9%, p=0.039). Both traditional and adjusted MPR values indicated a significantly better adherence to treatment with insulin glargine, compared with NPH insulin (table 2).

Table 2.

Follow-up treatment persistence, hypoglycaemia, healthcare utilisation and loss in productivity

| Insulin glargine (n=356) | NPH insulin (n=178) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persistence/adherence, n (%) or mean±SD | |||

| Treatment persistence | 186 (54.5) | 75 (43.8) | 0.0225 |

| Treatment persistence days | 283.85±96.92 | 261.77±103.35 | 0.0178 |

| MPR | 0.50±0.28 | 0.45±0.30 | 0.0418 |

| Adjusted MPR | 0.67±0.33 | 0.61±0.35 | 0.0380 |

| DACON | 30.6±21.1 | 35.8±31.9 | 0.0740 |

| Hypoglycaemia, n (%) or mean±SD | |||

| Patients with hypoglycaemia | 16 (4.4) | 8 (4.4) | 1.0000 |

| Hypoglycaemia claims/patient | 0.10±0.63 | 0.07±0.44 | 0.5902 |

| Healthcare utilisation, n (%) or mean±SD | |||

| Hospitalisations | 82 (23%) | 56 (31.4%) | 0.0360 |

| Total hospitalisation days | 1.29±4.54 (0) | 2.06±4.98 (0) | 0.0754 |

| # Hospitalisations/patient | 0.28±0.58 (0) | 0.41±0.73 (0) | 0.0353 |

| ER visits | 104 (29.2%) | 57 (32.0%) | 0.5049 |

| Endocrinologist visits | 68 (19.1%) | 48 (26.9%) | 0.0377 |

| Endocrinologist visits/patient | 0.61±1.57 (0) | 0.94±1.84 (0) | 0.0422 |

| Diabetes-related Hospitalisations | 45 (12.6%) | 27 (15.1%) | 0.4201 |

| Diabetes-related ER visits | 43 (12.0%) | 27 (15.1%) | 0.3186 |

| Loss in productivity, mean±SD | |||

| Short-term disability occurrences | 0.36±0.70 | 0.38 (0.70) | 0.7944 |

| Short-term disability days | 15.96±38.78 | 24.51±60.33 | 0.0862 |

DACON, daily average consumption; ER, emergency room; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of follow-up 1 year persistence days between insulin glargine and neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin.

Clinical outcomes

The clinical outcomes of the two agents were similar, both in terms of hypoglycaemia-related event rates and DACON (table 2).

Healthcare utilisation and cost

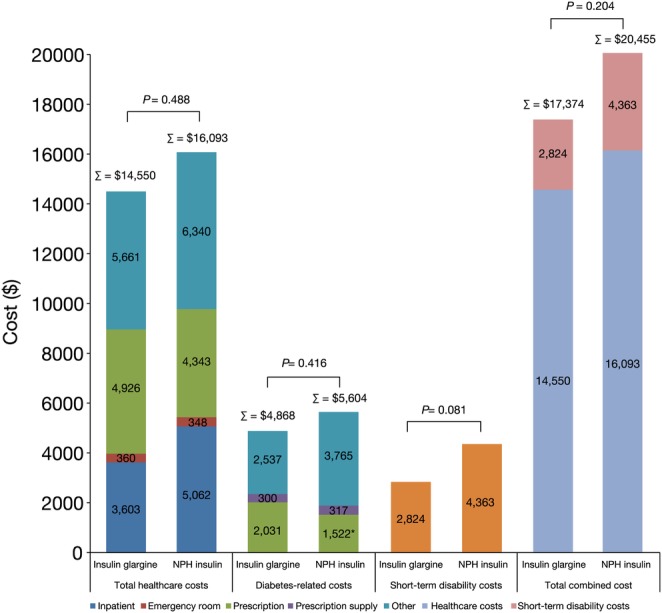

During follow-up, patients in the insulin glargine cohort had lower rates of hospitalisation and of endocrinologist visits, compared with those in the NPH insulin cohort (table 2). All diabetes-related healthcare utilisation outcomes were similar between the cohorts (table 2). With respect to cost outcomes, the total overall healthcare costs were similar for the insulin glargine and NPH insulin cohorts, as were the total diabetes-related healthcare costs. Similar total diabetes-related healthcare costs were reported despite significantly higher diabetes drug costs for the insulin glargine cohort, compared with the NPH insulin cohort (figure 2).

Figure 2.

One-year short-term disability and direct healthcare costs. (Total between-group differences did not reach statistical significance.) *p<0.0001 versus insulin glargine.

Loss in productivity and its associated costs

The incidence of claims for short-term disability was similar between the insulin glargine and NPH insulin groups. However, the total number of short-term disability days and the associated cost were numerically lower in the insulin glargine group (16 vs 24.5 days, p=0.086 and $2824 vs $4363, p=0.081, respectively; figure 2). The combined total costs were similar between the insulins ($17 374 for insulin glargine vs $20 455 for NPH insulin, p=0.204).

Correlations

Significant correlations between a lower rate of treatment persistence and a higher likelihood of hospitalisation (33.47% vs 22.22%, p=0.0045) and short-term disability (60.1% vs 15.7%, p<0.001) were found.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analyses using 1:1 (n=199, both cohorts) and 3:1 (n=480, insulin glargine; n=160, NPH insulin) PSM yielded similar results overall (data not shown).

Discussion

In this real-world study, the use of insulin glargine was associated with better persistence and adherence than NPH insulin. In addition, lower healthcare resource utilisation was associated with insulin glargine than NPH insulin, in terms of hospitalisations and endocrinologist visits, over 1 year of follow-up. Rates of hypoglycaemia-related events were similar with the two treatments. Furthermore, diabetes drug-related costs were higher with insulin glargine than with NPH insulin likely due to the higher drug price of insulin glargine and also the improved persistence/adherence associated with it. However, both total diabetes-related and total healthcare costs were similar in the two groups, as a consequence of the fewer hospitalisations, fewer total endocrinologist visits and lower inpatient costs associated with the use of insulin glargine, compared with NPH insulin. Diabetes-related hospitalisations and endocrinologist visits were also numerically lower in the group using insulin glargine but not statistically significant, probably due to the sample size and the inaccuracy of using the ICD-9-CM diagnosis code (250.xx) to capture diabetes-related events. In regard to the short-term disability in both primary and sensitivity analyses, numerically fewer short-term disability days and lower associated costs were reported in the insulin glargine cohort than in the NPH insulin cohort, but this was not significant. It is likely that the reduction in short-term disability is related to better persistence with treatment in the insulin glargine cohort. Indeed, the correlation analysis showed that treatment persistence and short-term disability were highly correlated.

A variety of studies comparing the economic outcomes of insulin glargine and NPH insulin in patients with T2DM have indicated that insulin glargine represents an economic treatment option, compared with NPH insulin. Once-daily insulin glargine has been shown to provide at least as effective glycaemic control as NPH insulin, and to be cost effective in a range of countries and settings.33–39

Basal insulin analogues have been shown to have several advantages compared with NPH insulin, including less pharmacological variability, a lower risk of hypoglycaemia and a greater impact on quality of life.18 20 21 40 The rates of hypoglycaemia-related events were, however, similar for insulin glargine and NPH insulin in this study. Since insulin glargine is associated with less hypoglycaemia than NPH insulin,20 the switch from NPH insulin to insulin glargine may usually be considered in patients with evidence of hypoglycaemia or an increasing incidence of hypoglycaemic events. The baseline hypoglycaemic event results between cohorts in this study were similar, and thus it is possible that the NPH insulin cohort in the present analysis may be skewed to patients with lower NPH insulin-related hypoglycaemia than expected.

The increased persistence associated with insulin glargine, as shown in this study, may lead to better clinical outcomes,41 and potentially improve work-related outcomes.9 12 19 Diabetes-related disability has been shown to result in loss of workplace productivity.42–46 In this study, we observed fewer short-term disability days in patients on insulin glargine, compared with those on NPH insulin. Although the differences were not statistically significant, these findings may suggest that initiation of therapy with insulin glargine could help increase workplace productivity among employed patients with T2DM compared with those initiating with NPH insulin.

As with all retrospective studies, issues of sampling bias should be taken into account when interpreting these results, which may introduce selection bias. The use of PSM methodology in this study should have helped reduce the impact of selection bias. In fact, three different matching ratios were tested, and all yielded similar findings. However, PSM very likely limited patients in the insulin glargine cohort to those most similar to the NPH insulin cohort and not to those patients with T2DM who use insulin in general. Further, some insulin patients may have been missed due to the availability of 90-day/mail order prescriptions resulting in their being missed during the 3-month baseline period.

This study has several limitations. Although the MarketScan data represent a large diverse population, the study only included information from mainly large, self-insured employers, whose employees were more likely to be located in certain geographic areas than the general employee population, and the analysis included a convenience sample of patients whose employer supplied productivity data. Therefore, this study should not be assumed to be representative of the overall US population. As with any retrospective observational study, causality of treatment effects cannot be established in this study. Although the PSM method was used to balance differences between the two groups included in the study, confounding by indication or prognosis may still have affected the outcomes observed. The use of PSM also led to a significant reduction in the sample size, particularly in the insulin glargine group, due to the required matching ratios, and a much smaller sample size in the NPH group. This may also make the study underpowered to detect all significant differences between treatment groups. In addition, the similar rate of hypoglycaemia observed between groups is inconsistent with that in the existing literature, as previous studies suggest a lower risk of hypoglycaemia with insulin glargine, compared with NPH insulin.15 33 It is unlikely that rates of hypoglycaemia would be captured with the same level of sensitivity in this retrospective analysis as they would in a randomised clinical trial. Moreover, the low overall hypoglycaemia rate in both cohorts may have resulted in insufficient statistical power to detect significant differences. Coding issues in the claim data may also have contributed to the lack of statistical robustness. DACON was measured based on pharmacy claim data and may not be accurate. For example, patients on a low dose are instructed to discard unused insulin (particularly in vials) after approximately 1 month; hence, pharmacy claim data can lead to an overestimation of DACON. However, this is unlikely to affect the study groups disproportionately because they had a similar proportion of patients using insulin pens (table 2). HbA1c data were not available, and therefore neither the effectiveness of glycaemic control nor the association with hypoglycaemia could be assessed. Finally, the 12-month follow-up period of this study may not have been sufficient to detect benefits due to improved persistence and adherence.

Conclusion

This study showed that insulin glargine resulted in better persistence and adherence, with lower healthcare utilisation, at similar total healthcare costs despite higher drug-related costs, than NPH insulin. Better persistence and adherence may lead to long-term health benefits and additional benefits to patients with T2DM and their employers. Owing to the retrospective nature of this study, further studies need to be conducted to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors received editorial and writing support in the preparation of this manuscript from Ewen Legg, PhD, of Excerpta Medica.

Footnotes

Contributors: LW participated actively in the study design, statistical plan, data analysis, drafting and review of the manuscript. WW and RM participated actively in creating the concept and study design, drafting and review of the manuscript. LX had an active role in the statistical analysis and review of the manuscript. OB participated actively in creating the study design, statistical plan and review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Sanofi U.S., Inc.

Competing interests: LW, LX and OB are employees of STATinMED Research, under contract with Sanofi U.S., Inc. RM and WW are employees of Sanofi U.S., Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The results from the sensitivity analyses of two different sets of propensity-score-matching. 1:1 and 1:3 are available by e-mailing Dr Onur Baser, obaser@statinmed.com.

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. National diabetes fact sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf (accessed 18 Jun 2012)

- 2.Morsanutto A, Berto P, Lopatriello S, et al. Major complications have an impact on total annual medical cost of diabetes: results of a database analysis. J Diabetes Complications 2006;20:163–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S. Burden of hospitalizations primarily due to uncontrolled diabetes: implications of inadequate primary healthcare in the United States. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1281–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durden ED, Alemayehu B, Bouchard JR, et al. Direct health care costs of patients with type 2 diabetes within a privately insured employed population, 2000 and 2005. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:1460–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007 Diabetes Care 2008;31:596–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillum LA, Gouveia C, Dorsey ER, et al. NIH disease funding levels and burden of disease. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e16837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattila TK, De Boer A. Influence of intensive versus conventional glucose control on microvascular and macrovascular complications in type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs 2010;70:2229–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asche C, LaFleur J, Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clin Ther 2011;33:74–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson TB, Song X, Alemayehu B, et al. Cost sharing, adherence, and health outcomes in patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:589–600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, et al. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 2005;43:521–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuart B, Davidoff A, Lopert R, et al. Does medication adherence lower Medicare spending among beneficiaries with diabetes? Health Serv Res 2011;46:1180–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sprince NL, Pospisil S, Peek-Asa C, et al. Occupational injuries among workers with diabetes: the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2005. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:804–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzo JA, Abbott TA, III, Pashko S. Labour productivity effects of prescribed medicines for chronically ill workers. Health Econ 1996;5:249–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenstock J, Davies M, Home PD, et al. A randomised, 52-week, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with insulin glargine when administered as add-on to glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2008;51:408–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenstock J, Dailey G, Massi-Benedetti M, et al. Reduced hypoglycemia risk with insulin glargine: a meta-analysis comparing insulin glargine with human NPH insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:950–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullins P, Sharplin P, Yki-Järvinen H, et al. Negative binomial meta-regression analysis of combined glycosylated hemoglobin and hypoglycemia outcomes across eleven phase III and IV studies of insulin glargine compared with neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther 2007; 29:1607–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Home PD, Fritsche A, Schinzel S, et al. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to assess the risk of hypoglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes using NPH insulin or insulin glargine. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010;12:772–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riddle MC. Making the transition from oral to insulin therapy. Am J Med 2005;118(Suppl 5A):14S–20S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clement S, Bowen-Wright H. Twenty-four hour action of insulin glargine (Lantus) may be too short for once-daily dosing: a case report. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1479–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, et al. Basal supplementation of insulin lispro protamine suspension versus insulin glargine and detemir for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2698–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1364–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito K, Capuano A, Giugliano D. Humalog (lispro) for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2012;12:1541–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooke CE, Lee HY, Tong YP, et al. Persistence with injectable antidiabetic agents in members with type 2 diabetes in a commercial managed care organization. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:231–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansà M, Hernández C, Vidal M, et al. Multidimensional analysis of treatment adherence in patients with multiple chronic conditions. A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis SN, Wei W, Garg S. Clinical impact of initiating insulin glargine therapy with disposable pen versus vial in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a managed care setting. Endocr Pract 2011;17:845–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie L, Wei W, Pan C, et al. A real-world study of patients with type 2 diabetes initiating basal insulins via disposable pens. Adv Ther 2011;28:1000–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie L, Zhou S, Wei W, et al. Does pen help? A real-world outcomes study of switching from vial to disposable pen among insulinglargine-treated patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther 2013;15:230–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baser O, Bouchard J, DeLuzio T, et al. Assessment of adherence and healthcare costs of insulin device (FlexPen) versus conventional vial/syringe. Adv Ther 2010;27:94–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Campbell CR, Fonseca V, et al. Impact of hypoglycemia associated with antihyperglycemic medications on vascular risks in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1126–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. J Occup Environ Med 2004;46:398–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkins K, Wang S, Rupnow MF. Indirect cost burden of migraine in the United States. J Occup Environ Med 2007;49:368–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhoads GG, Dain MP, Zhang Q, et al. Two-year glycaemic control and healthcare expenditures following initiation of insulin glargine versus neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011;13:711–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clissold R, Clissold S. Insulin glargine in the management of diabetes mellitus: an evidence-based assessment of its clinical efficacy and economic value. Core Evid 2007;2:89–110 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grima DT, Thompson MF, Sauriol L. Modelling cost effectiveness of insulin glargine for the treatment of type 1 and 2 diabetes in Canada. Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:253–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brändle M, Azoulay M, Greiner RA. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of insulin glargine compared with NPH insulin based on a 10-year simulation of long-term complications with the Diabetes Mellitus Model in patients with type 2 diabetes in Switzerland. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;45:203–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schöffski O, Breitscheidel L, Benter U, et al. Resource utilisation and costs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin glargine or conventional basal insulin under real-world conditions in Germany: LIVE-SPP study. J Med Econ 2008;11:695–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee LJ, Yu AP, Johnson SJ, et al. Direct costs associated with initiating NPH insulin versus glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective database analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:108–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brändle M, Azoulay M, Greiner RA. Cost-effectiveness of insulin glargine versus NPH insulin for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, modeling the interaction between hypoglycemia and glycemic control in Switzerland. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;49:217–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartman I. Insulin analogs: impact on treatment success, satisfaction, quality of life and adherence. Clin Med Res 2008;6:54–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei W, Pan C, Xie L, et al. Association of treatment persistence and adherence with real-world outcomes among insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Diabetes 2012;61:A4 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gore M, Brandenburg NA, Hoffman DL, et al. Burden of illness in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: the patients’ perspectives. J Pain 2006;7:892–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musich S, Hook D, Baaner S, et al. The association of two productivity measures with health risks and medical conditions in an Australian employee population. Am J Health Promot 2006;20:353–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Wyatt HR, et al. Productivity costs associated with cardiometabolic risk factor clusters in the United States. Value Health 2007;10:443–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Ben-Joseph RH. The effect of obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors on expenditures and productivity in the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2155–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kannan H, Thompson S, Bolge SC. Economic and humanistic outcomes associated with comorbid type-2 diabetes, high cholesterol and hypertension among individuals who are overweight or obese. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:542–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.