Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association between body mass index (BMI) in young adulthood and cardiovascular risks, including venous thromboembolism, before 55 years of age.

Design

Cohort study using population-based medical databases.

Setting

Outcomes registered from all hospitals in Denmark from 1977 onwards.

Participants

6502 men born in 1955 and eligible for conscription in Northern Denmark.

Main outcome measures

Follow-up began at participants’ 22nd birthday and continued until death, emigration or 55 years of age, whichever came first. Using regression analyses, we calculated the risks and HRs, adjusting for cognitive test score and years of education.

Results

48% of all obese young men (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) were either diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke or venous thromboembolism or died before reaching 55 years of age. Comparing obese men with normal weight men (BMI 18.5 to <25.0 kg/m2), the risk difference for any outcome was 28% (95% CI 19% to 38%) and the HR was 3.0 (95% CI 2.3 to 4.0). Compared with normal weight, obesity was associated with an event rate that was increased more than eightfold for type 2 diabetes, fourfold for venous thromboembolism and twofold for hypertension, myocardial infarction and death.

Conclusions

In this cohort of young men, obesity was strongly associated with adverse cardiometabolic events before 55 years of age, including venous thromboembolism. Compared with those of normal weight, young obese men had an absolute risk increase for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity or premature death of almost 30%.

Article summary.

Article focus

Little is known about the association between young adulthood obesity and long-term risks of venous thromboembolism and combined cardiometabolic outcomes.

We followed a cohort of 22-year-old men for 33 years to examine the association between young adulthood obesity and the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity and death before 55 years of age.

Key messages

Nearly 50% of obese young men were either diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke or venous thromboembolism or died before reaching 55 years of age.

Obese men had a fourfold increased rate of venous thromboembolism and a threefold increased rate of any of these diseases compared with men of normal weight, yielding an absolute risk increase of almost 30%.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The population-based design reduced potential selection biases, provided access to valid exposure and outcome data and ensured a complete 33-year follow-up for all persons.

Unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded due to the non-randomised design.

Introduction

Tripling in prevalence over the last three decades and now exceeding 30% in the USA,1–3 obesity in young adulthood is as a major public health concern worldwide, leading to a shorter lifespan for today's children.4 Despite the obesity epidemic, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality have continued to decrease in the Western world.5 6

Although obesity in adulthood is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes,1–3 7 cardiovascular disease4 8 and mortality,5 6 9 it remains unclear whether an elongated history of overweight, starting early in life, poses additional risks. Previous reports indicate that age modifies the effect of obesity on cardiovascular death with greater impact in younger age groups, including childhood and young adulthood.10 11 However, while obese children reduce their additional cardiovascular risks (compared with non-obese children) by ceasing to be overweight before adulthood,12 new studies indicate that the risks among obese young adults persist independently of weight changes in later adulthood.13 14 These findings emphasise the need to study the adverse outcomes associated with obesity within the age group of young adults specifically.

Several studies have examined the association between body mass index (BMI) in young adults and premature death.10 13 15–24 Fewer studies have examined long-term risks of type 2 diabetes14 and ischaemic heart disease.14 23 25 However, despite the link between atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome and venous thromboembolism,26–28 none of the previous studies have included venous thromboembolism as an outcome. Moreover, estimates of the absolute risk, in addition to the relative risk, of adverse events are important for clinical decision making, particularly when counselling patients on risk modification associated with weight, diet and exercise. Nonetheless, no study has examined the combined risk of type 2 diabetes, numerous cardiovascular outcomes and premature death in one study, thereby assessing the complete cardiometabolic risks associated with young adulthood obesity.

We therefore followed a cohort of 22-year-old men for 33 years to examine the association between BMI in young adulthood and the risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism and death before 55 years of age.

Methods

Setting

We conducted this population-based cohort study in the Fifth Military Conscription District in Denmark, populated by approximately 700 000 inhabitants.29 The Danish National Health Service provides universal tax-supported healthcare, guaranteeing unfettered access to general practitioners and hospitals and partial reimbursement for prescribed medications. Accurate and unambiguous individual-level linkage of all Danish registries is possible using the unique central personal registration number assigned to all residents at birth or upon immigration.30

Study cohort

Nearly all Danish men have had to register with the military board for an examination of fitness to serve when reaching 18 years of age or shortly thereafter (median age 19 years).31 In connection with the registration, all examinees complete a health questionnaire, in which they report chronic diseases that could preclude military service, for example, asthma, epilepsy or spinal osteochondrosis, but not obesity.3 The Draft Board verifies such reports with health care providers, and men deemed ineligible for military service are excused from the draft at this point (approximately 15%).32 Information obtained at the examination is registered and stored in regional and national databases.29 Using a conscription research database, we identified all persons from the 1955 birth cohort who later appeared before the draft board in Northern Denmark (n=6502).

Body mass index

All potential conscripts undergo a physical and mental examination. The physical examination includes measurements of height (without shoes) and body weight (wearing trunks only and using sliding scales and calibrated balances). Using these height and weight measurements, we calculated the BMI. Values of weight <45 kg (n=6) were considered to be data entry errors and recoded as missing. We categorised BMI as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5 to <25 kg/m2), overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2) or obese (≥30 kg/m2).

Covariates

From the conscription database, we obtained data on cognitive function as measured by the validated Boerge Prien test.31 33 The Boerge Prien test is a 78-item group intelligence test with four subscales (letter matrices, verbal analogies, number sequences and geometric figures) and a single final score, recorded as the number of correctly answered items (range 0–78).31 The scores are strongly correlated with conventional intelligence-test scores (eg, correlation of 0.82 with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale).31 Based on quartiles, we categorised the test scores as low (0–31), moderate (32–39), high (40–46) and very high (47–78).

From the conscription database, we also obtained information on years of education at the time of examination.33 Based on quartiles, we categorised the education length as short, moderate, long and very long.

Outcomes

The Danish National Registry of Patients records information on patients discharged from all Danish non-psychiatric hospitals since 1 January 1977 and from all emergency room and outpatient specialty clinic visits since 1995.34 Each hospital discharge or outpatient visit is recorded in the registry with one primary diagnosis and one or more secondary diagnoses classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision (ICD-8) until the end of 1993 and the 10th revision (ICD-10) thereafter.34

Using the Danish National Registry of Patients, we identified all examinees with a first diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke (ischaemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage or subarachnoid haemorrhage) or venous thromboembolism (deep venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism). To ensure more complete identification of examinees with type 2 diabetes, we also searched the Aarhus University Prescription Database,35 covering the study region, for any use of antidiabetic drugs from 1 January 1989 through 2010. ICD and ATC codes are provided as online supplementary material.

We obtained information on all-cause mortality from the Danish Civil Registration System.30 This registry has recorded all changes in vital status and migration for the entire Danish population since 1968, with daily electronic updates.30 Finally, a combined outcome was defined as the first-time occurrence of any of the individual outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Initially, we used descriptive statistics to characterise the study population by categories of BMI, cognitive test score and years of education. To ensure that the Danish National Registry of Patients (initiated in 1977) would capture events, follow-up started at the examinee’s 22nd birthday. We excluded all men who were censored between their date of examination and their 22nd birthday (17 died and 8 emigrated). Follow-up continued until the first occurrence of an outcome, emigration or 33 years of follow-up (ie, their 55th birthday), whichever came first. First, we illustrated graphically the association between BMI and the predicted cumulative incidence function for each outcome using the proportional subhazards model by Fine and Gray.36 We used the pseudo-value method to calculate the 33-year risk for each BMI group, as well as the risk differences compared with normal weight.37 We treated death as a competing risk in all analyses of non-fatal outcomes.

We calculated rates for each BMI group and used Cox proportional hazards regression to compute hazard ratios (HRs) associating BMI with all outcomes. BMI was analysed both as a categorical and continuous variable. For the categorical BMI variable, the proportional hazard assumption was assessed by log–log plots and Schoenfeld's test and found valid. We assessed the scale of the continuous BMI variable using fractional polynomials and found no evidence of non-linearity in the log hazard. We repeated all regression analyses adjusting for cognitive test score and years of education. As there was no recent validation study available for hypertension, we estimated the proportion of patients registered with hypertension in the Danish National Registry of Patients that also redeemed at least one prescription for antihypertensive medication (registered in the prescription database).

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2011-41-5807). All analyses were conducted in STATA software V.12.1 (STATA, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Characteristics

The characteristics of the study population are presented in table 1. We identified 6502 male examinees from the 1955 birth cohort in Northern Denmark. Among these, 5407 (83%) were of normal weight, 353 (5%) were underweight, 639 (10%) were overweight and 97 (1.5%) were obese. BMI ranged from a minimum of 14.4 kg/m2 to a maximum of 42.7 kg/m2. The median BMI was 21.7 kg/m2 (IQR 20.3–23.4 kg/m2). Compared with men of normal weight (25%), a higher proportion of those who were overweight (32%) or obese (41%) scored low on the cognitive test. Also, compared with subjects of normal weight (24%), a higher proportion of overweight (32%) or obese (33%) persons belonged to the lowest quartile of years of education. The validation analysis revealed that 88% of patients with a diagnosis of hypertension redeemed one or more prescriptions for antihypertensive medication.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at time of examination

| Body mass index* | Total, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal weight, n (%) | Underweight, n (%) | Overweight, n (%) | Obesity, n (%) | ||

| Total | 5407 (100) | 353 (100) | 639 (100) | 97 (100) | 6502 (100) |

| Cognitive test score | |||||

| Low | 1339 (25) | 87 (25) | 206 (32) | 40 (41) | 1676 (26) |

| Moderate | 1369 (25) | 84 (24) | 178 (28) | 24 (25) | 1655 (26) |

| High | 1396 (26) | 95 (27) | 160 (25) | 20 (21) | 1672 (26) |

| Very high | 1303 (24) | 87 (25) | 95 (15) | 13 (13) | 1499 (23) |

| Education (years) | |||||

| Short | 1277 (24) | 74 (21) | 202 (32) | 32 (33) | 1588 (24) |

| Moderate | 1506 (28) | 96 (27) | 176 (28) | 32 (33) | 1811 (28) |

| Long | 1645 (30) | 120 (34) | 181 (28) | 23 (24) | 1971 (30) |

| Very long | 979 (18) | 63 (18) | 80 (13) | 10 (10) | 1132 (17) |

*Body mass index groups were defined as underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5 to <25.0), overweight (25.0 to <30) and obese (≥30.0). Six persons had missing data.

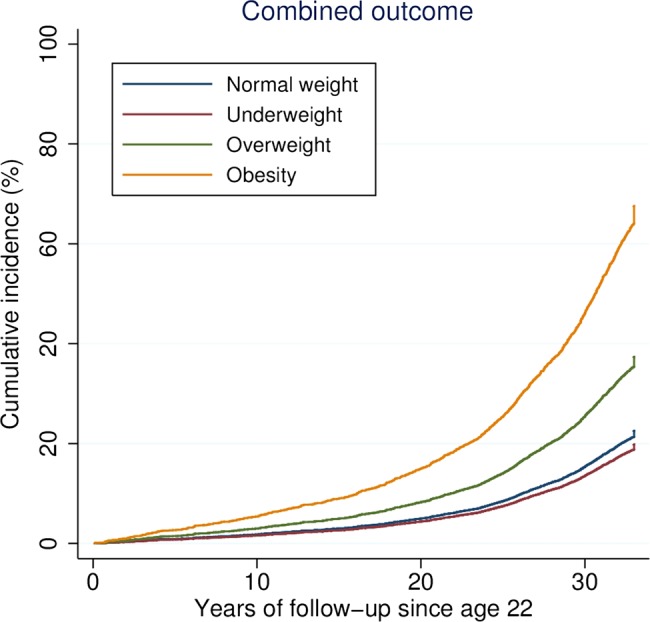

Combined outcome

The cohort contributed a total of 199 430 person-years of follow-up, providing a mean follow-up time of 31 years. Compared with 20% of men of normal weight, 48% of all obese men were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke or venous thromboembolism or died before their 55th birthday (table 2 and figure 1). After adjusting for cognitive test score and years of education, the absolute risk difference between the groups was 28% (95% CI 19% to 38%) and the HR was 3.0 (95% CI 2.3 to 4.0).

Table 2.

Body mass index in young adulthood and the combined risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism and death before age 55 years*

| BMI categories | Number | Risk, % (95% CI) | Risk difference†, % (95% CI) | Rate‡ (95% CI) | HR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined outcome | |||||

| Normal | 1083 | 20 (16 to 23) | 0 | 649 (612 to 689) | 1 |

| Underweight | 63 | 18 (12 to 23) | −2 (−6 to 2) | 574 (448 to 734) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Overweight | 205 | 31 (26 to 36) | 11 (7 to 15) | 1086 (947 to 1245) | 1.7 (1.4 to 1.9) |

| Obesity | 48 | 48 (38 to 59) | 28 (19 to 38) | 1814 (1367 to 2407) | 3.0 (2.3 to 4.0) |

*Among the 1955 birth cohort that appeared for military examination in Northern Denmark and who survived until their 22nd birthday.

†In all regression analyses, adjustments were made for cognitive test score and years of education.

‡Rates per 100 000 person-years.

BMI, body mass index.

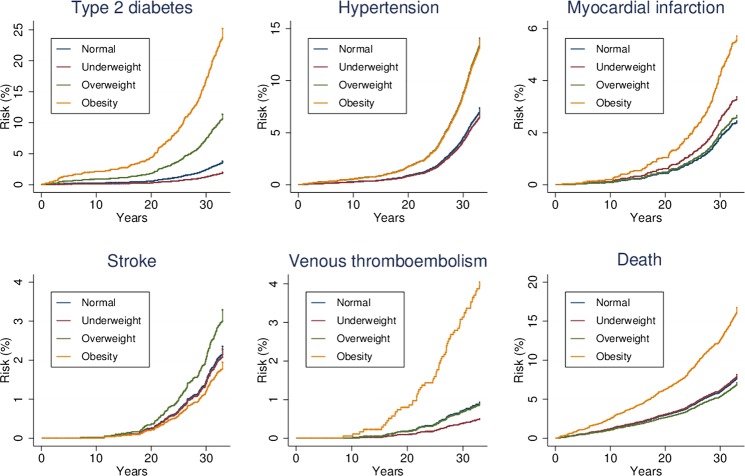

Figure 1.

Body mass index in young adulthood and predicted cumulative incidence (risk) of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism and death before age 55 years.

Individual outcomes

Obesity was strongly associated with all individual outcomes except stroke (table 3 and figure 2). With a risk difference of 22% (95% CI 13% to 31%) and HR of 8.2 (95% CI 5.4 to 12.3) the absolute and relative associations for obesity, compared with normal weight, were the strongest for type 2 diabetes. However, there was also a more than fourfold increased rate of venous thromboembolism and more than twofold increased rate of hypertension, myocardial infarction and death. For stroke, there was a 40% increased rate among overweight persons. The wide CIs made the association between obesity and stroke inconclusive. In the analysis of BMI as a continuous variable, a unit increase in BMI corresponded to an increased rate of approximately 5% for myocardial infarction, 10% for hypertension and venous thromboembolism and 20% for type 2 diabetes (table 4).

Table 3.

Body mass index in young adulthood and the risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity or death before age 55 years*

| BMI categories | Number | Risk, % (95% CI) | Risk difference†, % (95% CI) | Rate‡ (95% CI) | HR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 2 diabetes | |||||

| Normal | 207 | 5 (3 to 7) | 0 | 122 (106 to 139) | 1 |

| Underweight | 7 | 4 (1 to 6) | −2 (−3 to 0) | 63 (30 to 132) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) |

| Overweight | 76 | 13 (10 to 16) | 8 (5 to 10) | 387 (309 to 485) | 3.1 (2.4 to 4.0) |

| Obesity | 26 | 27 (18 to 36) | 22 (13 to 31) | 946 (644 to 1390) | 8.2 (5.4 to 12.3) |

| Hypertension | |||||

| Normal | 394 | 7 (4 to 9) | 0 | 233 (211 to 257) | 1 |

| Underweight | 24 | 6 (3 to 10) | 0 (−3 to 3) | 215 (144 to 321) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) |

| Overweight | 92 | 13 (10 to 17) | 7 (4 to 10) | 469 (382 to 575) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) |

| Obesity | 14 | 14 (7 to 21) | 8 (1 to 16) | 494 (292 to 833) | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| Normal | 134 | 3 (1 to 5) | 0 | 79 (66 to 93) | 1 |

| Underweight | 12 | 4 (1 to 6) | 1 (−1 to 3) | 107 (61 to 189) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) |

| Overweight | 18 | 3 (1 to 5) | 0 (−1 to 2) | 90 (56 to 142) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) |

| Obesity | 6 | 7 (2 to 11) | 4 (−1 to 9) | 208 (93 to 462) | 2.5 (1.1 to 5.6) |

| Stroke | |||||

| Normal | 128 | 2 (1 to 4) | 0 | 75 (63 to 89) | 1 |

| Underweight | 8 | 2 (0 to 4) | 0 (−2 to 2) | 71 (36 to 143) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) |

| Overweight | 22 | 3 (1 to 5) | 1 (−1 to 2) | 109 (72 to 166) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.2) |

| Obesity | 2 | 2 (−1 to 5) | 0 (−3 to 3) | 69 (17 to 276) | 0.9 (0.2 to 3.6) |

| Venous thromboembolism | |||||

| Normal | 57 | 2 (1 to 3) | 0 | 33 (26 to 43) | 1 |

| Underweight | 2 | 1 (0 to 3) | 0 (−1 to 0) | 18 (4 to 71) | 0.6 (0.1 to 2.3) |

| Overweight | 7 | 2 (0 to 3) | 0 (−1 to 1) | 35 (17 to 73) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) |

| Obesity | 5 | 6 (1 to 10) | 4 (0 to 8) | 173 (72 to 415) | 4.7 (1.9 to 11.9) |

| Death | |||||

| Normal | 416 | 7 (5 to 10) | 0 | 243 (220 to 267) | 1 |

| Underweight | 28 | 7 (3 to 11) | 0 (−3 to 2) | 249 (172 to 361) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| Overweight | 47 | 6 (3 to 9) | −1 (−3 to 1) | 232 (174 to 309) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Obesity | 16 | 16 (8 to 23) | 8 (1 to 16) | 547 (335 to 893) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.5) |

*Among the 1955 birth cohort that appeared for military examination in Northern Denmark and who survived until their 22nd birthday.

†In all regression analyses, adjustments were made for cognitive test score and education level. In all non-fatal outcomes, death was treated as a competing risk.

‡Rates per 100 000 person-years.

BMI, body mass index.

Figure 2.

Body mass index in young adulthood and cumulative incidence (risk) of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity or death before age 55 years (note that follow-up starts at age 22 and that the maximum risk is not constant on the y-axis of the various panels).

Table 4.

The association between a one-unit increase in body mass index in young adulthood and type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity or death before 55 years of age*

| Outcomes | HR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|

| Type 2 diabetes | 1.19 (1.16 to 1.22) |

| Hypertension | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.13) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) |

| Stroke | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.18) |

| Death | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) |

*Among the 1955 birth cohort that appeared for military examination in Northern Denmark and who survived until their 22nd birthday.

†BMI analysed as a continuous variable in a linear regression model adjusted for cognitive test score and education level.

BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

In this population-based 33-year follow-up study, we found that nearly half of all obese young men either were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke or venous thromboembolism or died before reaching 55 years of age. Obesity was associated with an event rate that, compared with normal weight, was increased more than eightfold for type 2 diabetes, fourfold for venous thromboembolism and twofold for hypertension, myocardial infarction, and premature death. The strong association between young adulthood obesity and venous thromboembolism was of particular importance because it, to our knowledge, has not previously been reported. Obese subjects had a threefold increased event rate of any of these diseases compared with persons of normal weight, yielding a notable absolute risk increase of almost 30%. The magnitude of the relative and absolute risk estimates emphasise the major clinical and public health implications associated with obesity in young adulthood.

Strengths and limitations of study

Several issues should be considered when interpreting our results. With military examination in anticipation of conscription being mandatory and participation enforced by law, the population-based design reduced potential selection bias. We used measured instead of self-reported height and weight. Doing so, we eliminated differential misclassification of BMI, which may have biased other studies13 16 because underweight people tend to overestimate their BMI and overweight people tend to underestimate their BMI.38 The Danish Civil Registration System ensured complete follow-up of all examinees with accurate mortality data.30 The tax-supported universal healthcare system allowed for complete ascertainment of all hospital admissions throughout the 33-year follow-up period. In addition to our estimate for hypertension (88%), the positive predictive values of diagnoses in the Danish National Registry of Patients have previously been validated and found to be approximately 90% for diabetes39 and myocardial infarction39 40 and 80% for stroke39 41 and venous thromboembolism.42

There were, however, some limitations. Examinees had to survive from their examination date until the start of follow-up at 22 years of age. Although BMI is a widely used proxy for adiposity, it does not distinguish adipose from muscle tissue nor does it take the anthropometric distribution of fat into account. Some degree of misclassification is therefore inevitable (for all studies on this topic). Nevertheless, BMI is a valuable tool to provide a standardised definition of obesity, allowing for a comparison of its associated risks across decades. The Aarhus University Prescription Database did not cover the entire study period. However, any potential underreporting of diabetes and hypertension in the Danish National Registry of Patients would provide underestimates of the absolute risks, and thus cannot explain the increased risks.

We cannot exclude confounding from exercise, diet, weight changes and smoking. An advantage of studying death rates among young subjects is that adjustments for other conditions are largely unnecessary. Moreover, analyses of myocardial infarction and death should not adjust for hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, diabetes or other factors associated with the metabolic syndrome because all of these risk factors may be on the causal pathway.43 We were unable to consider the impact of weight changes later in life. However, weight loss among obese or weight gain among normal weight conscripts would bias the results towards unity, and thus cannot explain our findings. Furthermore, other studies have found the associations between young adulthood BMI and coronary artery disease14 and death,13 independent of later weight changes. Smoking is associated with low and not high BMI.44 Thus, any unmeasured confounding from smoking would also tend to bias the results towards unity. Supporting the robustness of our results, previous studies on young obese adults have found similar death rates among smokers and non-smokers17 or even higher death rates among non-smokers.16 In addition, as a surrogate measure of lifestyle, we did adjust for cognitive test score and years of education. Finally, although the results derive from a study that included only young men, previous reports suggest the associations are likely also to hold for young women.45

Comparison with other studies

Our results are in line with previous reports on the individual outcomes. The increased premature mortality risk is consistent.10 13 15–24 Among prior studies, a similar Swedish study on male conscripts with mean age of 18.7 years found an almost identical association between obesity and premature mortality (HR 2.14, 95% CI 1.61 to 2.85).17 In contrast to the reports of a U-shaped relationship between BMI and mortality in young adults,15 our results supported the absence of any association between underweight and premature mortality.17

Our results for type 2 diabetes and myocardial infarction are also supported by previous reports. Reporting on the magnitude of the association between BMI and diabetes, a recent meta-analysis of 18 cohort studies reported relative risk estimates almost identical to ours for both overweight (2.92, 95% CI 2.57 to 3.32) and obesity (7.28, 95% CI 6.47 to 8.28).7 Tirosh et al14 also examined young adults and found an HR for each unit increase in BMI of 1.10 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.12) for diabetes14 and of 1.12 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.18) for coronary heart disease.14 In addition, a recent meta-analysis that pooled the results from seven studies of subjects between 18 and 30 years found a relative risk of 1.08 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.11) associating 1 kg/m2 higher BMI with coronary heart disease.25 Another recent meta-analysis28 found that obesity overall was associated with a twofold increased risk of venous thromboembolism. However, none of the included studies examined the risk among young adults specifically. Our finding of a more than fourfold increased risk in this age group is thus important.

Pathophysiological explanations and implications

There may be several pathophysiological explanations for our findings. First, the apparent higher cardiovascular risks associated with BMI in young adulthood compared with older adulthood10 11 may be caused by early development and clustering of cardiovascular risk factors, in particular the metabolic syndrome.46 Thus, overweight and obesity are both associated with insulin resistance, higher blood pressure and adverse blood lipid profiles.46 These risk factors increase short-term and long-term incidence of type 2 diabetes,46 venous thromboembolism,28 premature coronary artery disease (through enhanced progression of atherosclerosis)14 26 27 and finally, as a result, the cardiovascular death rate. Second, physical effects of body fat may limit venous return and create a proinflammatory, prothrombotic and hypofibrinolytic milieu that enhance venous thromboembolic risks.47

The current and projected continued increase in obesity prevalence1 48 may affect negatively the current trends of declining cardiovascular death rates.5 6 49 Thus, obesity-related morbidity and mortality will, in decades to come, place an unprecedented burden on healthcare systems worldwide.48 This forecast reinforces the importance of understanding the effects of adiposity in young adults to plan future strategies for weight management and primary prevention.

Conclusions

In this cohort of young men, obesity was strongly associated with adverse cardiometabolic events before 55 years of age, including venous thromboembolism. Compared with those of normal weight, young obese men had an absolute risk increase for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity or premature death of almost 30%.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MS and HTS conceived the study idea. MS designed the study. SPU and HTS collected the data. MS and HTS reviewed the literature. MS, SAJ, SL, TLL, HEB and HTS directed the analyses, which were carried out by MS. All authors participated in the discussion and interpretation of the results. MS organised the writing and wrote the initial drafts. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version. HTS is the guarantor.

Funding: The study was supported by Aarhus University Research Foundation, Department of Clinical Epidemiology's Research Foundation, ‘Augustinusfonden’, ‘Snedkermester Sophus Jacobsen & Hustru Astrid Jacobsens Fond’ and ‘Fabrikant Karl G. Andersens Fond’. The Department of Clinical Epidemiology is a member of the Danish Center for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes (Danish Research Council, grants 09-075724 and 10-079102). None of the funding sources had a role in the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of the study.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: As this study did not involve any contact with patients or any intervention, it was not necessary to obtain permission from the Danish Scientific Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 2010;303:235–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002;288:1723–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sørensen HT, Sabroe S, Gillman M, et al. Continued increase in prevalence of obesity in Danish young men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997;21:712–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1138–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Lash TL, et al. 25 year trends in first time hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, subsequent short and long term mortality, and the prognostic impact of sex and comorbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e356–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2012;366:54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdullah A, Peeters A, de Courten M, et al. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;89:309–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJE, Hoogenveen RT, et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1720–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prospective-Studies-Collaboration Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009;373:1083–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park HSH, Song Y-MY, Cho S-IS. Obesity has a greater impact on cardiovascular mortality in younger men than in older men among non-smoking Koreans. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:181–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, et al. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 2007;298:2028–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1876–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens JJ, Truesdale KPK, Wang C-HC, et al. Body mass index at age 25 and all-cause mortality in whites and African Americans: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Adolesc Health 2012;50:221–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tirosh A, Shai I, Afek A, et al. Adolescent BMI trajectory and risk of diabetes versus coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2011;364: 1315–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strand BH, Kuh D, Shah I, et al. Childhood, adolescent and early adult body mass index in relation to adult mortality: results from the British 1946 birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:225–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J, Flanders WD, Ward EM, et al. Body mass index in young adulthood and premature death: analyses of the US National Health Interview Survey linked mortality files. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:934–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neovius M, Sundstrom J, Rasmussen F. Combined effects of overweight and smoking in late adolescence on subsequent mortality: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2009;338:b496–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjørge T, Engeland A, Tverdal A, et al. Body mass index in adolescence in relation to cause-specific mortality: a follow-up of 230 000 Norwegian adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:30–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engeland AA, Bjørge TT, Tverdal AA, et al. Obesity in adolescence and adulthood and the risk of adult mortality. Epidemiology 2004;15:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffreys M, McCarron P, Gunnell D, et al. Body mass index in early and mid-adulthood, and subsequent mortality: a historical cohort study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:1391–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engeland AA, Bjørge TT, Søgaard AJA, et al. Body mass index in adolescence in relation to total mortality: 32-year follow-up of 227 000 Norwegian boys and girls. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:517–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engeland AA, Bjørge TT, Selmer RMR, et al. Height and body mass index in relation to total mortality. Epidemiology 2003;14:293–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarnell JWG, Patterson CC, Thomas HF, et al. Comparison of weight in middle age, weight at 18 years, and weight change between, in predicting subsequent 14 year mortality and coronary events: caerphilly prospective study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:344–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmermann E, Holst C, Sorensen TIA. Lifelong doubling of mortality in men entering adult life as obese. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:1193–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owen CG, Whincup PH, Orfei L, et al. Is body mass index before middle age related to coronary heart disease risk in later life? Evidence from observational studies. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:866–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lijfering W, Flinterman L, Vandenbroucke J, et al. Relationship between venous and arterial thrombosis: a review of the literature from a causal perspective. Semin Thromb Hemost 2011;37:885–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sørensen HT, Horvath-Puho E, Pedersen L, et al. Venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospitalisation due to acute arterial cardiovascular events: a 20-year cohort study. Lancet 2007;370:1773–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ageno W, Becattini C, Brighton T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2008;117:93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sørensen HT, Sabroe S, Rothman KJ, et al. Relation between weight and length at birth and body mass index in young adulthood: cohort study. BMJ 1997;315:1137–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teasdale TW. The Danish draft board's intelligence test, Børge Priens Prøve: psychometric properties and research applications through 50 years. Scand J Psychol 2009;50:633–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen GL, Dethlefsen C, Sørensen HT, et al. Cognitive function and army rejection rate in young adult male offspring of women with diabetes: a Danish population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2827–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teasdale TW, Hartmann PVW, Pedersen CH, et al. The reliability and validity of the Danish Draft Board Cognitive Ability Test: Børge Prien's Prøve. Scand J Psychol 2010;52:126–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehrenstein V, Antonsen S, Pedersen L. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: Aarhus University prescription database. Clin Epidemiol 2010;2:273–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fine J, Gray R. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parner ET, Andersen PK. Regression analysis of censored data using pseudo-observations. Stata J 2010;10:408–22 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keith SW, Fontaine KR, Pajewski NM, et al. Use of self-reported height and weight biases the body mass index-mortality association. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:401–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joensen AM, Jensen MK, Overvad K, et al. Predictive values of acute coronary syndrome discharge diagnoses differed in the Danish National Patient Registry. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:188–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krarup L-H, Boysen G, Janjua H, et al. Validity of stroke diagnoses in a National Register of Patients. Neuroepidemiology 2007;28:150–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Overvad K, et al. Venous thromboembolism discharge diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry should be used with caution. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;63:223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology. 3rd edn Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albanes D, Jones DY, Micozzi MS, et al. Associations between smoking and body weight in the US population: analysis of NHANES II. Am J Public Health (N Y) 1987;77:439–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Dam JE, Willett RM, Manson WC, et al. The relationship between overweight in adolescence and premature death in women. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:91–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanhala MM, Vanhala PP, Kumpusalo EE, et al. Relation between obesity from childhood to adulthood and the metabolic syndrome: population based study. BMJ 1998;317:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allman-Farinelli M. Obesity and venous thrombosis: a review. Semin Thromb Hemost 2011;37:903–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, et al. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity 2008;16:2323–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson P, Pletcher MJ, et al. Adolescent overweight and future adult coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2371–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.