Abstract

Objectives

To determine the sensitivity and specificity of the whispered voice test (WVT) in detecting hearing loss when administered by practitioners with different levels of experience.

Design

Diagnostic accuracy study of WVT, through acoustic analysis of whispers of experienced and inexperienced practitioners (experiment 1) and behavioural validation of these recordings (experiment 2).

Setting

Research institute with a pool of patients sourced from local clinics in the Greater Glasgow area.

Participants

22 people had their whispers recorded and analysed in experiment 1; 4 older experienced (OE), 4 older inexperienced (OI) and 14 younger inexperienced (YI). In experiment 2, 73 people (112 individual ears) took part in a digit recognition task using 2 OE and 2 YI whisperers from experiment 1.

Main outcome measures

Average level (dB sound pressure level) across frequency, average level across all utterances (dB A) and within/across-digit deviation (dB A) for experiment 1. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of WVT for experiment 2.

Results

In experiment 1, OE whisperers were 8–10 dB more intense than inexperienced whisperers across all whispered utterances. Variability was low and comparable regardless of age or experience. In experiment 2, at an optimum threshold of 40 dB HL, sensitivity and specificity were 63% (95% CI of 58% to 68%) and 93% (92% to 94%), respectively, for OE whisperers. PPV was 56% (51% to 61%), NPV was 95% (94% to 96%). For YI whisperers at an optimum threshold of 29 dB HL, sensitivity and specificity were 80% (78% to 82%) and 52% (50% to 55%), respectively. PPV was 65% (63% to 67%) and NPV was 70% (67% to 72%).

Conclusions

WVT is an effective screening test, providing the level of the whisperer is considered when setting the test's hearing-loss criterion. Possible implications are voice measurement while training for inexperienced whisperers.

Keywords: Sensitivity, Specificity, Hearing Tests

Article summary.

Article focus

Practitioners experienced in administering the whispered voice test (WVT) have previously shown high sensitivity and specificity.

There is a lack of research in the literature on the diagnostic accuracy of the test when it is administered by inexperienced practitioners.

This study investigates the effect of experience on the diagnostic accuracy of WVT. How well do the recorded whispers of experienced and inexperienced practitioners screen for hearing loss?

Key messages

For a given whisperer, variability in the level across sessions and digits remained comparatively low and was not dependent on experience.

Across all recorded digits, experienced whisperers were 8–10 dB greater in level than inexperienced whisperers.

The level of the whisperer affects the test's performance, particularly if the whisperer is inexperienced.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study provides both an acoustic analysis and behavioural validation of WVT.

We used a closed set of responses, the digits 1–9, omitting letters and words sometimes used in the test.

Introduction

The whispered voice test (WVT) is an efficient screening test for detecting hearing loss. A tester stands behind and to the side of the patient, at arm's length from the patient's non-test ear, and whispers sets of either three digits or a combination of digits and letters. If the patient cannot repeat back over 50% of the test items over a minimum of two sets, they are assumed to have an impairment worthy of full audiometric assessment.1 WVT has high sensitivity and specificity for adults if administered by an experienced practitioner,2–5 though with less success in children.6 The test has been used in large-scale trials of approximately 15 000 people7 and is continually recommended clinically as a simple test of hearing ability.8 It is the only test of hearing that requires no equipment at all. It would therefore be particularly valuable in situations where resources are limited.

A potential problem with WVT is the whispers are spoken live, not prerecorded. Random intensity differences may therefore occur which could affect the test results.9 In addition, there are some other common disadvantages to free-field voice tests10: the failure to standardise the technique used, the inability to control the pitch of a whisper, the lack of control of background noise and the different acoustic properties of test environments. A review examining the accuracy of WVT indicated that the problems of variations in technique and intensity are particularly relevant.11 Only one study has quantified the variability in acoustic intensity of a set of English spoken digits, letters and words in a variant of WVT used by the US Federal Highway Administration.12 It found that this variant was not being administered as specified and showed high variability in the sound pressure level (SPL) of whispers, both between stimuli and between whisperers.

Currently, no data exist on the level of training or experience necessary to achieve high sensitivity and specificity values from WVT. The only data available where WVT was validated by pure tone audiometry were those conducted by specialised professionals, for example, otolaryngologists, geriatricians or audiologists with previous experience of the test. There is one large-scale study which used trained practice nurses to administer the test, but it did not include an audiometric assessment to validate the results; nor was the amount or nature of the training specified.7 If experience does affect the sensitivity and specificity of WVT, then a substantial proportion of patients may be incorrectly diagnosed. This is important in two ways: a patient classed as normal-hearing when in fact they are impaired will not be referred for audiometric assessment, which may lead to social isolation, reduced quality of life and other associated health problems,13 whereas a patient incorrectly classed as hearing-impaired would lead to a costly and unnecessary referral to an audiology department.

The present study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of WVT when administered by experienced and inexperienced practitioners, using both acoustic analyses and behavioural validation. The importance is that if experience does not affect sensitivity and specificity, then WVT could become a more viable screening tool, especially in resource-limited or equipment-limited situations where a simple, fast test of hearing is needed.

Methods

Experiment 1: acoustic analysis of whispered digits

The whispers of three groups of individuals were recorded and subject to acoustic analysis. The purpose was to quantify the variation in level of the whispers, across digits, person and day.

Design and setting

The acoustic analysis employed three study groups: (1) an older experienced (OE) group, to establish the variability of professionals experienced in performing WVT, (2) an intermediary group of older inexperienced (OI) whisperers, to determine if age was a factor in any acoustic differences and (3) a larger, younger inexperienced (YI) group, to assess the variability of inexperienced whispers (we were unable to locate people for a potential fourth group, younger but experienced practitioners). The experiments were conducted at the Scottish Section of the MRC Institute of Hearing Research (IHR), located within the Glasgow Royal Infirmary (GRI), UK. All data were anonymised with an index number and stored at IHR. Only the authors had access to the data.

Study population

Participants from all three groups were recruited between August 2011 and February 2012. On their initial visit, each participant filled in a questionnaire relating to their first language, ethnicity and experience of WVT. The OE group consisted of four otolaryngologists (all men, age range 50–70 years) recruited from the GRI ear, nose and throat (ENT) department (1 retired). Two were the authors of the original WVT paper. All were native speakers of British English. The OI group consisted of four older men (age range 41–51 years; one US English speaker and three British English speakers), with no experience of WVT, who were recruited later from IHR to determine if age was a factor in the intensity of whispers. The YI group was comprised of 14 inexperienced young adults (7 men, 7 women and age range 22–31 years) recruited from the University of Glasgow School of Medicine and IHR: 11 British English speakers, 1 Singaporean with English as a first language, 1 Italian and 1 Belgian with Italian and French as their first language, respectively.

The inclusion criteria for the OE group were that they had used WVT professionally and had at least 20 years’ experience in administering the test. The inclusion criteria for both the OI and YI groups were that they had not received training and had not used the test professionally or in their medical or scientific studies. An additional inclusion criterion for the OI group only was that their mean age was between that of the OE and YI groups. The exclusion criteria for all groups were if they currently smoked or if they had suffered voice strain in the last 2 weeks; neither of these criteria led to any exclusions.

Test methods

An acoustic mannequin (Bruel & Kjaer Head and Torso Simulator, type 4100-D) was mounted on a tripod placed inside a sound-proofed audiometric booth and connected to an amplifier (Bruel & Kjaer Sound Quality Conditioning Amplifier, type 2672). The output of the amplifier was routed to a DAT recorder (Marantz PMD690/W1B) operating at a 16-bit, 48 kHz sampling rate. To ensure that the levels were consistent across multiple sessions, at the start of each session the ears of the mannequin were temporarily removed and a Bruel & Kjaer Calibrator (type 4230) placed over the microphones to record 1 kHz calibration tones at 94 dB SPL.

The stimuli were the digits 1–9. We omitted the letters of the alphabet, even though they are sometimes included in WVT, in order to reduce the recording and editing times. For each participant in each session, a list was produced that contained six rows of the digits 1–9. The first row was labelled ‘conversational level’: participants were asked to say the nine digits using their normal conversational voice as a warm-up. The remaining five rows were labelled ‘exhaled whisper level’: participants were instructed to exhale fully before uttering each of these digits. The position of the digits in each row was randomised using Fisher's complete sets of orthogonal Latin squares and arranged in triplets.14 The lists were displayed directly ahead of the participants, who were instructed to position themselves relative to the mannequin by placing their left hand on the mannequin's left tragus. With their left arm outstretched to maintain the appropriate distance of approximately 0.6 m, they stood behind and slightly to the right of the mannequin's right ear (the recorded ear). Three sessions were recorded over three different days for each participant, giving 15 utterances of each whispered digit. The duration between each participant's recordings ranged from 1 day up to 3 weeks.

All the recordings were edited in Adobe Audition 2.0 (Adobe Systems Inc). A preset high-pass filter with a cut-off of 100 Hz was applied to reduce any mains or equipment hum before each digit was isolated and saved. All further processing was performed in Matlab (V.7.0.4, The Mathworks Inc). Levels were computed in one-third octave bands from 100 to 8000 Hz, weighted by the standard ‘A’-weighting filter. All recordings and editing were conducted by one of the authors.

The outcome measures for experiment 1 were average level across frequency bands (dB SPL), across all whispered utterances (dB A), within digit deviation (dB A) and across digit deviation (dB A). For all outcome measures, the mean value of the OE group was used as the reference standard, the rationale being that two of the four OE whisperers had shown high sensitivity and specificity values (at least 86% and 90%, respectively) in previously published studies examining WVT as a screening instrument.1 2

Experiment 2: digit recognition task

The recordings of two OE whisperers and the least-variable YI male and female whisperers were presented to the participants in a digit recognition task analogous to WVT. The purpose was to quantify experimentally the effect of the differences in the two groups of whisperers, using typical pure tone audiometry as the reference test.

Study population

Participants were recruited from the available pool of patients at IHR. At the time of their invitation, no details of their hearing ability were known. The reference test was a pure-tone audiometric assessment conducted immediately before the digit recognition task.15 All participants were treated as two single individual ears. Inclusion followed successful completion of the audiogram, with a three-frequency (0.5, 1 and 2 kHz) pure-tone average threshold of less than 65 dB HL in the ear to be tested. A short pilot experiment had shown that participants with a threshold greater than this generally could not perform the task, so any ear with this level of impairment was excluded from the digit recognition task (n=34 ears) to avoid undue stress.

Sample size

Based on results from previous studies using a similar population, where the prevalence of hearing impairment >30 dB HL was 43%, we anticipated that clinicians would expect at least 86% sensitivity and 90% specificity.1 2 We calculated that to obtain an estimate of sensitivity and specificity within ±10% of the anticipated values (ie, to have 95% CIs equal to or less than 10% around those values), we required 108 individual ears.16 In total, 112 ears were tested.

Test methods

After a reference audiogram, participants were seated in the audiometric booth wearing headphones (AKG 720). The time interval between audiometric testing and the experimental run was at most a few minutes, being the time taken to explain the task. The stimuli were presented via PC, sound card and amplifier (Arcam A80) to the headphones. If applicable, the order of testing the left and right ears was randomised. For the four whisperers chosen, all five runs from each of the three sessions were used giving 60 trials per ear. The order of trials was randomised for each participant, and all the digits presented in a trial were from the same whisperer, session and run.

First, a practice trial was given using the conversational-level recordings of one otolaryngologist, to ensure that participants could hear the digits while practising the task. Each trial consisted of at least two sequences of three digits, presented at a duty cycle of 0.8 s per digit. The digits were randomly chosen each time. After the first sequence, a keypad was presented to the listener on a touch screen. Participants responded by entering the digits they heard and were presented with the second sequence. If after their second response they had scored <50%, the trial was a fail. If they scored >50%, the trial was a pass. If they had scored 50%, they were presented with the final three digits from the set of nine. The total score was then calculated across all nine digits, again with a >50% correct requirement for a pass.

The stimuli were the recordings of the whispers made in experiment 1 from either two members of the OE group (as two previous studies using their whispered voices showed high sensitivity and specificity values) or the least-variable YI male and female whisperers. Onset and offset gates (5 ms) were applied to each digit to reduce any editing artefacts. To overcome the unrealistic nature of listening in a sound-proofed booth, a 2.6 s portion of a recording of the background noise of a typical ENT clinic room was randomly selected and presented simultaneously.

One audiologist or one of two research assistants administered the reference audiogram and the digit recognition task. All were trained and experienced in doing so. They were not blinded to the results of either test, but they had no control over the level of the whispers delivered by the headphones—as it was controlled by a prewritten computer programme—so they could not influence the digit recognition task. Two of the authors analysed the results. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of WVT at various levels of hearing loss were calculated for both the OE and YI stimuli. The continuity-corrected Wilson score method was used to calculate 95% CIs.17 18

Results

Experiment 1

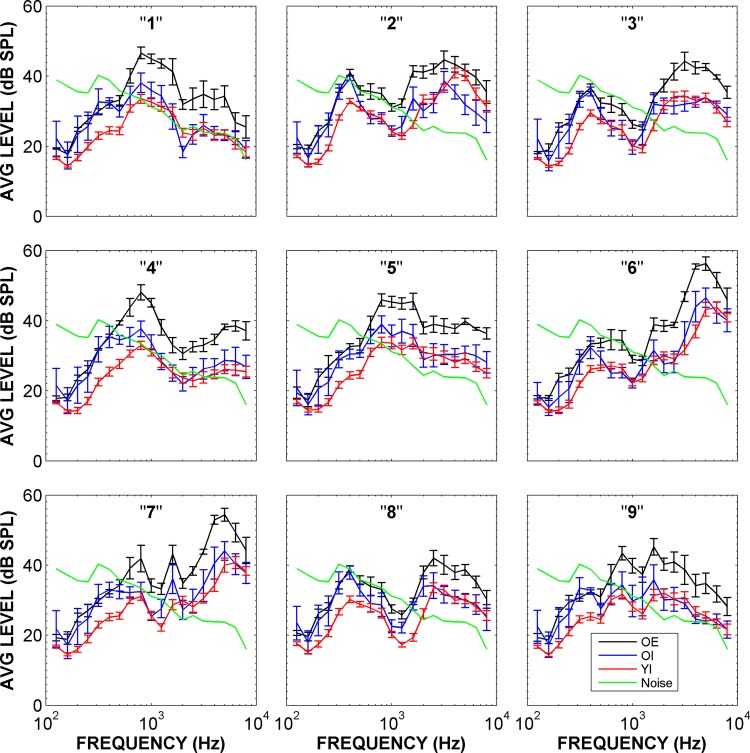

Figure 1 shows the results of the one-third octave analysis of the whispers. Each individual digit has a distinct spectrum, as would be expected from the many studies of speech. Across all whispered digits, the mean level of the OE group (black line) was approximately 8–10 dB greater than the means of other groups (blue and red lines) (see also table 1). These mean differences between the experienced and inexperienced groups were statistically significant (F(2,171)=75.4, p<0.001). While the individual differences in level were substantial, the within-whisperer variability across groups was similar. This indicated that experience affected the overall whisper level, but neither experience nor age affected the variability of whisper levels. Within-digit variability was low for all groups, at 2–3 dB. Across-digit variability was higher for all groups, at 5–6 dB, though the mean values for the OE and YI groups were comparable. Note that some degree of acoustic masking could be expected from the clinic room noise (green line), particularly at frequencies below 500 Hz.

Figure 1.

Average level (dB sound pressure level) for each digit across three sessions as a function of frequency for three whisperer groups (older experienced, older inexperienced and younger inexperienced) showing±1 SD. Clinic-room noise superimposed to show possible masking effects.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for all groups showing 95% CIs (*)

| Group | OE | OI | YI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean L (dB A) across all digits | 54 (50 to 58)* | 46 (39 to 53) | 44 (42 to 47) |

| Mean σ (dB A) within digits | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.0) | 2.8 (2.6 to 2.9) |

| Mean σ (dB A) across digits | 5.4 (4.1 to 6.8) | 6.2 (4.8 to 7.7) | 5.5 (5.0 to 6.0) |

Mean level (L, dB A) across all digits. Mean deviation (σ, dB A) within digits, that is, the mean of the mean deviation of each individual digit in the range 1–9. Mean deviation (σ, dB A) across digits, that is, the mean deviation across the full range of 1–9. All mean values reported are averaged across all whisperers in each group for all three sessions.

OE, older experienced; OI, older inexperienced; YI, younger inexperienced.

Experiment 2

Seventy-three participants were recruited between April 2012 and June 2012: 42 men (mean age 63.2 years, range 32–73 years) and 31 women (mean age 62.1 years, range 35–73 years). From the total of 146 ears, 112 individual ears were tested and 34 ears were excluded from testing after an audiogram due to the level of impairment being ≥65 dB HL. The three-frequency (0.5, 1 and 2 kHz) PTA values of the ears tested ranged from 8 to 63 dB HL. The mean 3F PTA across all ears tested in experiment 2 was 29 dB HL (SD 10.5 dB HL). Assuming a hearing-impairment criterion of 30 dB HL, 59 of the 112 ears (53%) exceeded this criterion.

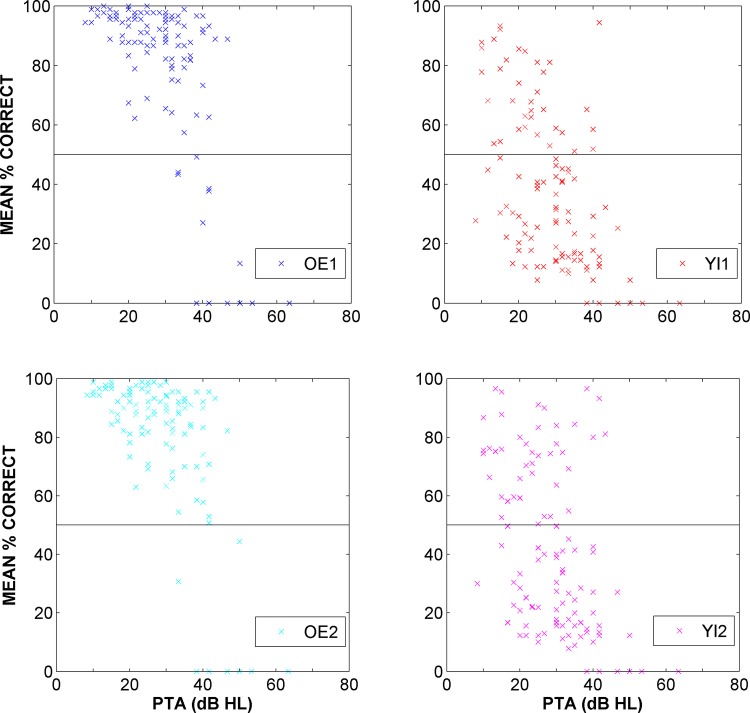

Figure 2 shows the results of the digit-recognition task using OE and YI whisperers. Each data point represents the mean per cent correct over 15 trials using one whisperer as a function of each participant's 3F PTA. Data points above the 50% threshold indicate a pass. It can be seen that the spread of the data depends on the experience of the whisperer: both OE whisperers exhibit a clear cut-off of passes versus fails around 40 dB HL while both YI whisperers show a lower, less clear cut-off around 30 dB HL. For YI whisperers, a substantial number of participants failed to achieve over 50% correct even when their 3F PTA was below 30 dB HL. As would be expected, the performance of the participants reduced with increasing 3F PTA.

Figure 2.

Mean per cent correct over 15 simulated whispered voice test trials as a function of three-frequency pure-tone average (PTA) hearing loss for 112 individual ears tested with the recordings of 2 older experienced and 2 younger inexperienced whisperers. Data points above the 50% threshold indicate a pass.

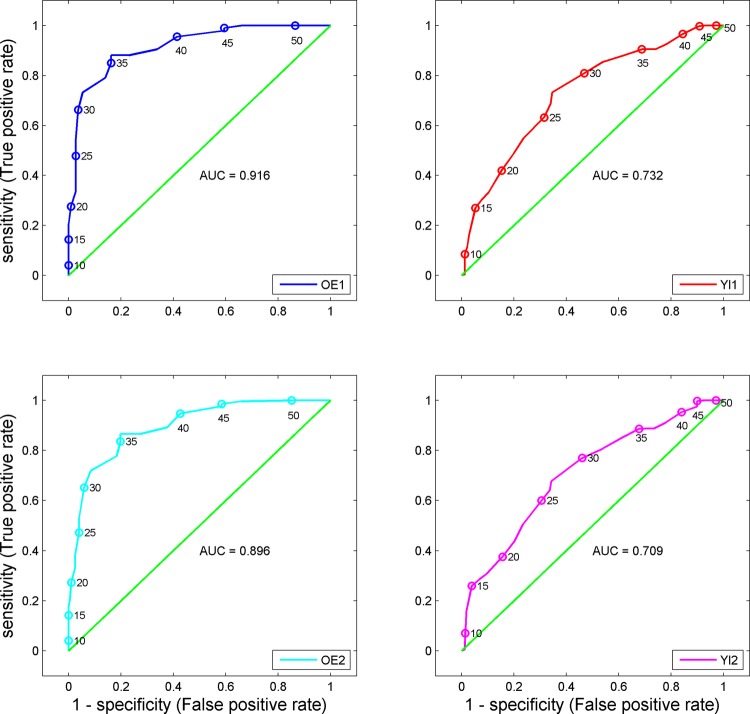

From these behavioural results, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed (IBM SPSS V.19) to provide a summary statistic of the accuracy of WVT (see figure 3). The area under the curve (AUC) represents the ability of the test to correctly classify those who have passed and failed the test. OE1 AUC was 0.916 (95% CI 0.897 to 0.935), whereas OE2 AUC was 0.896 (0.873 to 0.918). YI1 AUC was 0.732 (0.706 to 0.757), whereas YI2 AUC was 0.709 (0.683 to 0.734). For both OE and YI whisperers, the test outcome was greater than chance, but the OE whisperers would be expected to correctly classify approximately 20% more cases than the YI whisperers.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis for experienced and inexperienced whisperers, showing sensitivity as a function of false-positive rate for each whisperer (separate panels). Points along the curve are labelled in 5 dB HL increments, and the total area under the curve is given below the diagonal.

In order to identify the optimum threshold for discrimination of hearing loss, we computed the d-prime (d’), the distance from the diagonal in an ROC curve over a range of criteria values for hearing impairment (10–50 dB HL in 1 dB increments). To avoid cases in which sensitivity and specificity were high, producing large d’ values, but PPV and NPV, respectively, were low, we chose to limit the optimal thresholds to those where all the four diagnostic measures were greater than 50%. Using this criterion, the optimum pass/fail criterion occurred at 3F PTA of 40 dB HL for the OE group and at 29 dB HL for the YI group (table 2). We also computed Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC),19 another single indicator of reliability, for the same range of sensitivity and specificity values as a further corroboration. The maximum MCC, indicating optimum discrimination, occurred at a 3F PTA of 38 dB HL for the OE group and 29 dB HL for the YI group. The MCC results were nearly identical to the optimal threshold determined by d’; since the sensitivity for the OE results at 38 dB HL was less than 50%, we chose 40 dB HL as the optimum threshold for that dataset. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy and MCC for OE and YI whisperers with thresholds of 29 and 40 dB HL are shown in table 2. The OE results at 40 dB HL showed much higher accuracy than the YI results at 29 dB HL (23%), comparable to the respective difference in AUC found in the ROC analysis (figure 3). The OE whisperers also showed a dramatically higher specificity but lower sensitivity than YI whisperers.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) and accuracy (all as percentages), as well as Matthew's correlation coefficient (MCC) for OE and YI whisperers at two levels of hearing loss, 29 and 40 dB HL (3F PTA)

| (3F PTA) dB HL | Group | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | OE | 23 (21 to 25) | 98 (97 to 99) | 93 (90 to 95) | 53 (52 to 55) | 59 | 0.31 |

| YI | 80 (78 to 82) | 52 (50 to 55) | 65 (63 to 67) | 70 (67 to 72) | 67 | 0.33 | |

| 40 | OE | 63 (58 to 68) | 93 (92 to 94) | 56 (51 to 61) | 95 (94 to 96) | 90 | 0.54 |

| YI | 87 (83 to 90) | 38 (37 to 40) | 16 (14 to 17) | 96 (94 to 97) | 44 | 0.17 |

The 95% CIs shown in parentheses for sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were obtained using the continuity-corrected Wilson score method. Bold type indicates optimum values occur at different levels of hearing loss for each group.

OE, older experienced; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; YI, younger inexperienced.

While we used the 3F PTA values to classify hearing impairment in participants to comply with previous studies,1–3 hearing impairment is also classified using a four-frequency average (4F PTA) of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz. We therefore repeated the analysis using 4F PTA values for comparison to 3F PTA results. Optimal thresholds increased slightly to 30 and 43 dB HL for YI and OE whisperers, respectively (table 3). For OE whisperers, the accuracy of the test was unchanged at the 43 dB HL threshold (90%), while at the 30 dB threshold the accuracy of the test was reduced from 59% to 47%. For YI whisperers at the 43 dB threshold, the accuracy of the test increased from 44% to 54%, and at the 30 dB threshold, accuracy increased from 67% to 75%. At their respective optimal thresholds, both OE and YI whisperers had large increases in PPV and small reductions in NPV. Specificity increased from 52% to 65% for YI whisperers while sensitivity was unchanged. A small increase in specificity (93% to 98%) and a small reduction in sensitivity (63% to 56%) occurred for OE whisperers. Small increases in the MCC value occurred for both groups at their optimal thresholds.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) and accuracy (all as percentages), as well as Matthew's correlation coefficient (MCC) for OE and YI whisperers at two levels of hearing loss, 30 and 43 dB HL (4F PTA)

| (4F PTA) dB HL | Group | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | OE | 19 (18 to 21) | 100 (99 to 100) | 99 (97 to 100) | 40 (38 to 42) | 47 | 0.27 |

| YI | 80 (78 to 81) | 65 (62 to 68) | 81 (79 to 83) | 63 (60 to 66) | 75 | 0.44 | |

| 43 | OE | 56 (52 to 60) | 98 (97 to 99) | 88 (84 to 90) | 90 (89 to 91) | 90 | 0.65 |

| YI | 97 (95 to 98) | 44 (42 to 46) | 30 (28 to 32) | 98 (97 to 99) | 54 | 0.34 |

The 95% CIs shown in parentheses for sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were obtained using the continuity-corrected Wilson score method. Bold type indicates optimum values occur at different levels of hearing loss for each group.

OE, older experienced; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; YI, younger inexperienced.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

The acoustic data demonstrate that the whispers from experienced practitioners of WVT were on average 8–10 dB greater in level than whispers from those without experience. The variability in level, both within and across digits, and across sessions, was not dependent on experience. But the overall level differences across groups are a concern to those performing WVT, as they lead to differences in the performance of the test. Variability in the whispered digit level was roughly equivalent across groups (see table 1), and deviations are similar to the previously reported audiometric testing variability.20 Interobserver reliability was found to be low in a previous study, but the amount of experience or age of the whisperers was unspecified.9 The sensitivity and specificity values for the test were highest at different levels of impairment for different groups of whisperers: 29 dB HL for YI whisperers and 40 dB HL for OE whisperers. The ROC analysis AUC value suggests that WVT is an ‘excellent’ test for experienced whisperers but only an ‘acceptable’ test for inexperienced whisperers.21 This is perhaps overstating the overall discriminatory power of the test. Accuracy levels were as low as 47% at a 4F PTA of 30 dB HL using OE whisperers but reached 90% accuracy at 40 (3F PTA) and 43 dB HL (4F PTA).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strength of this study is that it provides both an acoustic analysis and behavioural validation of WVT. The acoustic analysis showed clear level differences based on the experience with the test, but there were no clear differences in level variance. The behavioural validation showed clear differences in the optimal threshold of WVT based on the tester's experience. Another strength of this study was that both the OE whisperers used in experiment 2 were the authors of two previous studies of WVT.1 2 There they reported that the majority of those with ≤30 dB HL could hear a whispered voice at a distance of 60 cm while the majority of those with ≥30 dB HL threshold could not. This provided a baseline of the diagnostic accuracy that OE whisperers could achieve. It is possible that using two authors from previous studies on WVT as whisperers is not a representative sample of the OE population and is potentially a weakness of our study. However, both had at least 20 years’ experience in administering the test and the results from their studies were comparable to others in which other authors also administered the test.3 6 No other studies have been found which identify what a representative sample of the OE population would be.

A potential weakness is that the increased threshold of 40 dB HL for the experienced whisperers in this study may be due to the differences between our laboratory validation and clinical practice (eg, prerecorded stimuli delivered via headphones, and a closed set of responses). Based on our results, the test appears to be less reliable in those patients with lower levels of impairment who would benefit most from screening for hearing loss. Unlike clinical testing where a patient is not given any indication of what is being whispered, participants in this study were given a closed set of responses (ie, the digits 1–9), potentially inflating their results.

Another weakness of the current study is that other potential tokens such as letters or words were not tested. This decision was made due to experimental time constraints. Nevertheless, we doubt that the acoustics of the whispering of single letters or words would be so different to the whispering of single digits that the results would be affected substantially. Despite these potential weaknesses, our results do show that experience does affect the sensitivity, specificity and overall accuracy of WVT.

Meaning of the study: possible mechanisms and implications for policy makers

This study raises the question of training in the use of WVT. The study by Smeeth et al7 used trained practice nurses, but the amount of training and experience was unspecified. It is also not clear whether the majority of those who regularly administer the test have ever measured their whispered voice level, and if so, in what setting. It is obviously impractical to measure voice level before administering the test in common practice; however, we believe that training in WVT should include voice level measurement. We therefore do not recommend that WVT be administered by an inexperienced practitioner who does not know the acoustic level of their whispers.

An experienced and properly trained practitioner could provide substantial cost benefits when screening for hearing loss. WVT can be administered in less than 1 min in any quiet setting, in comparison to an expensive and time-consuming referral to an audiology department. The low variability in level is commensurate with (more expensive) prerecorded calibration.

Unanswered questions and future research

We classified whisperers into two groups, experienced and inexperienced. It would be useful to extend this to a continuous dimension of experience rather than a binary classification.

All of the participants in experiment 2 of this study, both whisperers and listeners, were British with English as a first language. Given the spectrotemporal variation in digits across languages, similar results could be expected for other languages common to both the whisperer and the listener. When applied in a listener’s non-native language, performance in speech recognition is often worse,22 but it is unclear how whispered speech performance would be affected. Despite its drawbacks, WVT remains the only test of hearing that needs no equipment and can therefore be used in many circumstances where other hearing tests would be unwelcome. Further investigation and refinement of the test would be valuable. It would be of particular interest to know (1) if people can be trained to reliably produce whispers at a given—not their innate—level, (2) how the level of whispers depends on whether they are made before or after exhaling and (3) how using more than one trained whisperer in the test affects the sensitivity and specificity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants from both experiments; Patrick Howell, Neil Kirk and Kay Foreman for collecting the data; Oliver Zobay for his statistical advice; Professor George Browning for his advice and assistance with this study and the reviewers for their comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: WMW and DM participated in the study design, supervised recruitment of participants and analysed the data. All authors drafted the manuscript and/or contributed to its revision, and approved the final version. DM is the guarantor.

Funding: The Scottish section of IHR is supported by an intramural funding from the Medical Research Council (grant number U135097131) and the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government.

Competing interests: None.

None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the West of Scotland research ethics service (WoS REC(4) 09/S0704/12). All participants gave informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Browning GG, Swan IR, Chew KK. Clinical role of informal tests of hearing. J Laryngol Otol 1989;103:7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swan IR, Browning GG. The whispered voice as a screening test for hearing impairment. J R Coll Pract 1985;35:197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacPhee GA, Crowther JA, McAlpine CH. A simple screening test for hearing impairment in elderly patients. Age Ageing 1988;17:347–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uhlmann RF, Rees TS, Psaty BM, et al. Validity and reliability of auditory screening tests in demented and non-demented older adults. J Gen Intern Med 1989;4:90–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott CA, Omoding SS, Fermor J, et al. An evaluation of the ‘voice test’ as a method for assessing hearing in children with particular reference to the situation in developing countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;51:165–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempster JH, Mackenzie K. Clinical role of free-field voice tests in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1992;17:54–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smeeth L, Fletcher AE, Ng ES, et al. Reduced hearing, ownership, and use of hearing aids in elderly people in the UK—the MRC Trial of the Assessment and Management of Older People in the Community: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2002;359:1466–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn TJ, McArthur K, Ellis G, et al. Functional assessment in older people. BMJ 2011;343:d4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eekhof JA, de Bock GH, de Laat JA, et al. The whispered voice: The best test for screening for hearing impairment in general practice? Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:473–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King PF. Some imperfections of the free-field voice tests. J Laryngol Otol 1953;67:358–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirozzo S, Papinczak T, Glasziou P. Whispered voice test for screening for hearing impairment in adults and children: systematic review. BMJ 2003;327:967–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SE. Role of driver hearing in commercial motor vehicle operation: an evaluation of the FHWA hearing requirement [dissertation]. Blacksburg, VI: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arlinger S. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss—a review. Int J Audiol 2003;42(Suppl 2):2S17–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher RA, Yates F. Statistical tables for biological agricultural and medical research. 6th edn Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd Ltd., 1938 [Google Scholar]

- 15.British Society of Audiology Recommended procedures for pure tone audiometry using a manually operated instrument. Br J Audiol 1981;15:213–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenn Buderer NM. Statistical methodology: I. Incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:895–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blyth CR, Still HA. Binomial confidence intervals. J Am Stat Assoc 1983;78:108–16 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd edn New York: Wiley, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews BW. Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim Biophys Acta 1975;405:442–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell RW, Hartley BPR. Variability in audiometric recording. Brit J Industr Med 1972;29:432–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd edn New York: Wiley, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wijngaarden SJ, Steeneken HJ, Houtgast T. Quantifying the intelligibility of speech in noise for non-native listeners. J Acoust Soc Am 2002;111:1906–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.