Abstract

Objectives

Although cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy are equally effective in the acute treatment of adult depression, it is not known how they compare across the longer term. In this meta-analysis, we compared the effects of acute phase CBT without any subsequent treatment with the effects of pharmacotherapy that either were continued or discontinued across 6–18 months of follow-up.

Design

We conducted systematic searches in bibliographical databases to identify relevant studies, and conducted a meta-analysis of studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Setting

Mental healthcare.

Participants

Patients with depressive disorders.

Interventions

CBT and pharmacotherapy for depression.

Outcome measures

Relapse rates at long-term follow-up.

Results

9 studies with 506 patients were included. The quality was relatively high. Short-term outcomes of CBT and pharmacotherapy were comparable, although drop out from treatment was significantly lower in CBT. Acute phase CBT was compared with pharmacotherapy discontinuation during follow-up in eight studies. Patients who received acute phase CBT were significantly less likely to relapse than patients who were withdrawn from pharmacotherapy (OR=2.61, 95% CI 1.58 to 4.31, p<0.001; numbers-needed-to-be-treated, NNT=5). The acute phase CBT was compared with continued pharmacotherapy at follow-up in five studies. There was no significant difference between acute phase CBT and continued pharmacotherapy, although there was a trend (p<0.1) indicating that patients who received acute phase CBT may be less likely to relapse following acute treatment termination than patients who were continued on pharmacotherapy (OR=1.62, 95% CI 0.97 to 2.72; NNT=10).

Conclusions

We found that CBT has an enduring effect following termination of the acute treatment. We found no significant difference in relapse after the acute phase CBT versus continuation of pharmacotherapy after remission. Given the small number of studies, this finding should be interpreted with caution pending replication.

Keywords: Mental Health

Article summary.

Article focus

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy are equally effective in the acute treatment of depression.

Long-term differential effects are not well known.

Key messages

When acute phase CBT (without continuation treatment) was compared with acute phase pharmacotherapy that was discontinued during 6–18 months’ follow-up, we found that acute phase CBT was clearly more effective.

We found no significant difference between acute phase CBT (without continuation treatment) and acute phase pharmacotherapy with continued pharmacotherapy during follow-up, although there was a trend indicating that there may be such a difference favouring acute phase CBT.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Too few studies have examined the long-term effects of treatments for depressive disorders.

Introduction

It is well established that cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is efficacious in the treatment of adult depression. Dozens of randomised trials have shown that CBT is superior to no treatment, non-specific controls or care-as-usual in the acute treatment of adult depression,1 2 and that the effects of CBT are comparable to those of antidepressant pharmacotherapies, albeit with lower rates of attrition for CBT.3

What is not clear, however, is how acute CBT compares with pharmacotherapy over the longer term. It has long been claimed that psychotherapy leads to lasting change because patients learn skills that can be implemented after the treatment has ended and because they are instructed on specific techniques on how to handle relapse. CBT has been found to have an enduring effect that lasts beyond the end of treatment.4 No such claim has ever been made for pharmacotherapy.5 Nonetheless, it is well established that keeping patients on pharmacotherapy even after they are better can reduce the risk of subsequent symptom return, and it is standard practice to keep patients with chronic or recurrent depressions on pharmacotherapy indefinitely.6

If CBT has an enduring effect that extends beyond the end of treatment, it is important to know how that compares with simply keeping patients on pharmacotherapy. This is important from a clinical point of view, since clinicians and patients have to decide which modality to choose at the outset of treatment and will want to consider information about the relative long-term effects of each in their initial decision.

Improvement during acute treatment is called response and the full normalisation of symptoms is called remission.7 Recently remitted patients typically are kept on continuation pharmacotherapy for another 6–12 months in order to reduce the risk of relapse, the return of symptoms associated with the treated episode, and patients who have gone that long without relapse are said to be recovered, with the presumption that the underlying episode has run its course. Keeping recovered patients on maintenance pharmacotherapy beyond that point is intended to reduce the risk for recurrence, the onset of a wholly new episode, and is standard for chronic or recurrent patients.7

Although several studies have compared the long-term effects of acute CBT with those of continuation pharmacotherapy, no meta-analysis of these studies has been conducted. One earlier review examined whether the acute phase CBT had an enduring effect relative to medication withdrawal, but no direct comparison was made against continuation pharmacotherapy.8 Since the continued prescription of pharmacotherapy is now the current standard of treatment and the key decision that clinicians need to make, we decided to conduct such a meta-analysis.

In this meta-analysis, we focus on two research questions. The first question is whether acute phase CBT without continuation treatment is as effective as acute phase pharmacotherapy treatment with continuation treatment. The second question is whether acute phase CBT without continuation treatment is as effective as acute phase pharmacotherapy treatment without continuation treatment.

Methods

Identification and selection of studies

We used a database of 1344 papers on the psychological treatment of depression described in detail elsewhere9 that has been used to conduct a series of published meta-analyses (http://www.evidencebasedpsychotherapies.org). This database is continuously updated through comprehensive literature searches (from 1966 to January 2012). In these searches, we examined 13 407 abstracts in PubMed (3320 abstracts), PsycInfo (2710), EMBASE (4389) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2988). These abstracts were identified by combining terms indicative of psychological treatment and depression (both MeSH terms and text words). We also checked the references from 42 meta-analyses of psychological treatment for depression to ensure that no published studies were missed. From the 13 407 abstracts (9860 after removal of duplicates), 1344 full-text papers were retrieved for possible database inclusion.

We included (a) randomised trials (b) in which the effects of CBT (c) according to the manual by Beck et al10 (c) were compared with the effects of pharmacological treatment (d) in adults (e) with a diagnosed depressive disorder, (f) across a follow-up period of 6–18 months. We focused on studies that compared acute CBT (without subsequent continuation) versus pharmacotherapy that was either continued or withdrawn, and conducted separate comparisons on each.

Studies in which CBT was continued during follow-up were excluded, although we allowed a maximum of five booster sessions during follow-up, as long as these were not regularly planned. We set the limit at five booster sessions because most of the psychological treatments have six or more treatment sessions.11 We also excluded studies in which depression was not diagnosed with a standardised diagnostic interview (such as Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders or Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview), as well as studies in inpatients and adolescents. No language restrictions were applied.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The validity of included studies was assessed on four criteria of the ‘risk of bias’ assessment tool developed by the Cochrane Collaboration to assess the possible sources of bias in randomised trials: (1) adequate generation of allocation sequence, (2) concealment of allocation to conditions, (3) prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (blinding) and (4) dealing with incomplete outcome data.12 The two other criteria of the ‘risk of bias’ assessment tool were not used in this study, because we found no clear indication in any of the studies that these had influenced the validity of the study (suggestions of selective outcome reporting and other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias).

We collected characteristics of the target population (method of recruitment, definition of depression), HAMD score (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) at the start of the treatment to assess the severity of depression, whether all randomised patients were examined at follow-up or only responders to acute phase treatment, the number of treatment sessions, type of drug, whether pharmacotherapy was continued across the full follow-up or only for part of that period, and the country where the study was conducted. If all information was not reported in the paper, we contacted the authors of the papers requesting additional information (all six of whom responded).

Meta-analyses

For each study, we used the number of patients who responded to treatment and remained well as outcome measures (the exact definition of the outcome in each study was reported in table 1, column ‘outcome’). We calculated the OR of a positive outcome in CBT compared with pharmacotherapy. We calculated these ORs at the end of the acute treatment (response or remission) and across the subsequent follow-up (freedom from relapse or recurrence). Although at least some of the follow-ups were long enough for patients free from relapse to have met the criteria for recovery (and subsequent episodes of recurrences); we will use the term relapse to refer to all instances of symptom return.

Table 1.

The selected characteristics of the studies comparing the long-term effects of CBT for adult depression with those of pharmacotherapy

| Recr | DD | Pre-HAMD | Included* | Psychotherapy |

Pharmacotherapy |

FU | Outcome | C | Quality |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase | Nsess | Continuation phase | N | Acute phase | Continuation phase | N | SG | AC | BA | CF | ||||||||

| Blackburn et al21 | Clin | MDD (PSE/RDC) | NR | Resp | CBT | 23 | 4 Boosters (in the first 6 months) | 13 | Drug of choice | Continuation of 6 months, remaining period naturalistic | 9 | 24 | Depressive symptoms needing further treatment | UK | − | − | − | − |

| David, et al22 | Com+clin | MDD (DSM-IV)+BDI≥20+HAMD 17≥14 | 22.1 | All | CBT | 20 | Maximum three booster sessions | 56 | Fluoxetine | Continued pharmacotherapy | 57 | 6 | No current MDD+HAMD≤7 | RO | + | + | + | + |

| Dobson, et al23 | Com+clin | MDD (DSM-IV)+BDI-II≥20+HAMD 17≥14 | 20.7 | Resp | CBT | 24 | No treatment offered during FU | 30 | Paroxetine | Continued pharmacotherapy | 28 | 12 | Sustained response (no 2 weeks HAMD≥14) | USA | + | + | + | + |

| Evans, et al24 | Clin | MDD (RDC) | 26.9 | Resp | CBT | 20 | No continued treatment | 10 | Imipramine | Continued pharmacotherapy during 1 year, then tapered | 11 | 24 | No relapse (BDI≥16 during at least 2 weeks)+no treatment | USA | + | + | + | + |

| Hollon, et al25 | Com/clin | MDD (DSM-IV) | 23.4 | Resp | CBT | 20 | Up to three booster sessions | 60 | Paroxetine | Continued pharmacotherapy | 34 | 12 | No relapse (no HAMD≥14 for two consecutive weeks) | USA | + | + | + | + |

| Jarret, et al26 | Com/clin | Atypical MDD (DSM-IV; SCID) | 18.4 | Resp | CBT | 20 | No continued treatment | 6 | Phenelzine | Continued pharmacotherapy | 6 | 24 | Relapse/recurrence according to RDC | USA | + | + | + | + |

| Kovacs, et al27 | Com/clin | DD (Feigh-ner)+HAMD 17≥14+BDI≥20 | 21.5 | Resp | CBT | 20 | Naturalistic | 18 | Imipramine | Naturalistic | 17 | 12 | All monthly BDI scores during FU≤16 | USA | + | + | − | − |

| Shea, et al28 | Clin | MDD (RDC)+HAMD≥14 | 19.6 | All | CBT | 18 | Naturalistic | 59 | Imipramine | Pharmacotherapy was gradually reduced | 57 | 18 | Recovered (LIFE-II) and no relapse (MDD/RDC) | USA | + | + | + | + |

| Simons, et al29 | Clin | DD (DIS)+HAMD≥14 or BDI≥20 | 19.9 | Resp | CBT | 20 | No additional treatment | 19 | Nortriptyline | Pharmacotherapy was gradually tapered | 16 | 12 | Did not re-enter treatment+no BDI≥16 at FU | USA | + | + | − | + |

*Only responders to the acute phase treatments or the ones who completed the acute phase treatment were included in the FU analyses.

AC, allocation concealment; All, all randomised patients; BA, blind assessment; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; C, country; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; CF, completeness of FU data; clin, clinical recruitment; com, community recruitment; DD, depressive disorder; DIS, diagnostic interview schedule; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition; FU, follow-up; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; LIFE-II, longitudinal interval FU evaluation; MDD, major depressive disorder; Nsess, number of sessions; NR, not reported; PSE, present state examination; RDC, research diagnostic criteria; Recr, recruitment; Resp, only responders to the acute phase; RO, Romania; SG, sequence generation; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders.

To calculate the pooled ORs, we used the computer program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (V.2.2.021). We calculated the pooled ORs with the fixed effects model as well as with the random effects model. The calculations were conducted according to the procedures given by Borenstein et al.13 Because the results of these analyses being almost identical, we only report the results of the random effects model.

The numbers-needed-to-be-treated (NNT) is intuitively easier to understand than OR. NNT indicates the number of patients that would have to be treated in order to generate one additional positive outcome.14 Therefore, we also calculated NNT for all comparisons. We calculated the risk differences (RDs) for each study, pooled these for all the studies, and then calculated the NNT as 1/RD for the pooled studies.

As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I2 statistic, an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values show increasing heterogeneity, with 25% as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity.15 We calculated 95% CIs around I2,16 using the non-central χ2-based approach within the heterogi module for Stata.17

Subgroup analyses between different subsamples of studies were conducted according to the mixed effects model. In this model, studies within subgroups are pooled with the random effects model, while tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted with the fixed effects model.

Publication bias was tested by inspecting funnel plots on the primary outcome measures and by Duval and Tweedie's18 trim and fill procedure, which yields an estimate of the effect size after adjusting for publication bias (as implemented in Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, V.2.2.021). We conducted Egger's test of the intercept as well as Begg and Mazumdar's test to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and test whether it was significant.19 We also calculated Orwin's fail-safe N, which indicates the number of missing studies needed to make the effect size insignificant.20

Results

Selection and inclusion of studies

After examining a total of 13 407 abstracts (9860 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 1344 full text papers for further consideration. We excluded 1335 of the retrieved papers. The flow chart describing the inclusion process, including the reasons for exclusion, is presented in figure 1. In total, 9 of the 1344 retrieved full-text papers reported long-term outcomes of the acute phase CBT and were included in this meta-analysis.21–29

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion of studies.

Characteristics of the included studies

In the nine included studies, a total of 506 patients participated, 271 in CBT and 235 in pharmacotherapy. The selected characteristics of the included studies are presented in table 1.

Four studies recruited patients only from clinical samples, while the other five also recruited patients from the community. Six studies included only patients who responded to acute phase treatment in the analyses of the subsequent follow-ups, while the other three included all patients randomised to acute phase treatment. The number of CBT treatment sessions ranged from 18 to 24. During the follow-up phase (after acute treatment had ended), three studies offered up to four CBT booster sessions, while the other six did not offer any additional treatment.

In five earlier studies, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) was used in the pharmacotherapy condition, while the three more recent studies all used a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI); in one study, phenelzine (a monoamine oxidase inhibitor) was used. In four studies, patients who responded to pharmacotherapy were randomised to either continuation pharmacotherapy (for the first year of the 2-year follow-up) or pharmacotherapy withdrawal with each reported separately. In three other trials, all the patients were withdrawn from pharmacotherapy, although the length of the taper differed across the trials. One other trial continued pharmacotherapy for the first 6 months follow-up before subsequent withdrawal, and in the remaining trial, pharmacotherapy was continued throughout the follow-up. In most instances, patients withdrawn from treatment were followed naturalistically, although in several studies they were encouraged not to seek additional treatment until a relapse or recurrence was documented. Seven studies were conducted in the USA, two in Europe (one in the UK and one in Romania).

Quality of included studies

Eight of the nine studies used an adequate sequence generation strategy and had an independent party conceal allocations to conditions. Six studies reported keeping the assessors blind to treatment condition and seven studies conducted intent-to-treat analyses. The six studies published in the last two decades met all four of the quality criteria; among the three earlier studies, one study met three, another met two, and yet another met none of the criteria (table 1). The overall quality of the studies was relatively high, compared with the quality of the studies on psychotherapy for adult depression in general.30

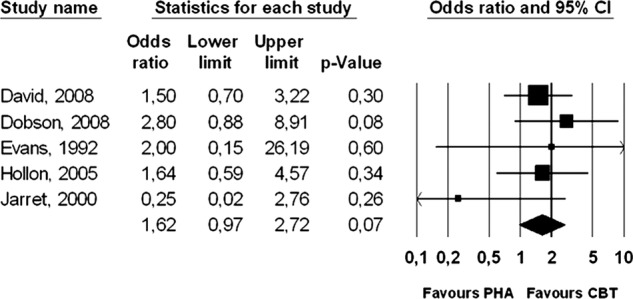

Long-term outcomes: acute phase CBT versus continuation pharmacotherapy

Five studies compared the 1-year outcomes of acute phase CBT (with nothing more than occasional booster sessions) versus continuation pharmacotherapy.22–26 There was a trend (p<0.1) indicating that the acute phase CBT outperformed continuation pharmacotherapy (OR=1.62, 95% CI 0.97 to 2.72). Heterogeneity was zero, but the 95% CI was broad (0% to 79%), so this finding should be interpreted with caution. NNT was 10. ORs and 95% CIs are presented graphically in figure 2. After exclusion of a possible outlier, OR was significant (OR=1.77, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.01; NNT=8). As can be seen, however, the pooled ORs are heavily reliant on just two studies, although most of the studies pointed in the same direction. The results should therefore be considered with caution.

Figure 2.

Long-term effects of cognitive behaviour therapy (without continuation during follow-up) compared with pharmacotherapy (continued during follow-up): Forest plot of OR of response.

We found no indication of publication bias (not surprising given the dearth of studies). Using Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure to adjust for publication bias did not change OR (the number of trimmed studies was zero). Egger's test and Begg and Mazumbar's test were not significant (p>0.1). We also calculated Orwin's fail-safe N and found that 23 studies with an OR of 0.9 or eleven studies with an OR of 0.8 (in favour of pharmacotherapy) or 7 studies with an OR of 0.7 would be needed to produce a pooled OR of 1.00. No additional subgroup analyses were conducted because of the small number of studies.

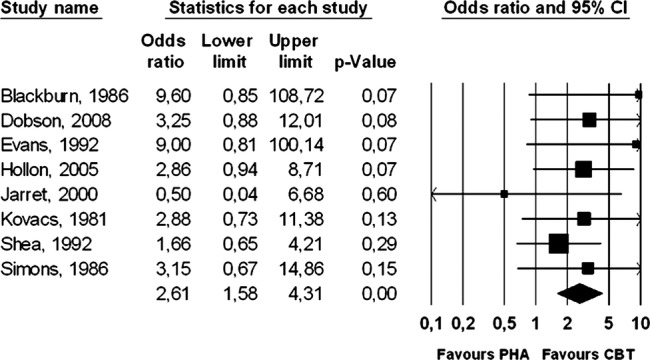

Long-term outcomes: acute phase CBT versus pharmacotherapy discontinuation

Eight studies compared the 1-year outcomes of acute phase CBT (with nothing more than occasional booster sessions) versus pharmacotherapy discontinuation or a naturalistic design. The acute phase CBT significantly outperformed the pharmacotherapy discontinuation condition to an even greater extent than it had continuation pharmacotherapy (OR=2.61, 95% CI 1.58 to 4.31; p<0.001). Heterogeneity was zero, but again the 95% CI was broad (0% to 68%). The corresponding NNT was 5 (95% CI 4 to 11). ORs and 95% CI for each study are presented graphically in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Long-term effects of cognitive behaviour therapy (without continuation during follow-up) compared with pharmacotherapy (discontinued during follow-up): Forest plot of OR of response.

Because two studies had a very high OR21 24 and one had a very low OR,26 we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis with these studies removed. The resulting OR was somewhat smaller (OR=2.47, 95% CI 1.45 to 4.22), though still highly significant (p<0.001), and the corresponding NNT was 6 (95% CI 4 to 15). Again, these results were heavily reliant on just two studies, and the results should be considered with caution.

Although the number of studies was small, we did conduct some subgroup analyses. We did not find any significant differences between subgroups, including medication type (SSRI vs TCA), whether all randomised patients were included versus inclusion of responders to the acute phase only, and studies with the highest quality (meeting all 4 criteria) versus those with lower quality (≤3 criteria). These outcomes should be interpreted with caution, however, because of the small sample sizes in the subgroups.

Short-term outcomes

We also examined the comparative effects of CBT versus pharmacotherapy in the short term (end of acute treatment), but found no significant difference (OR=1.15, n.s.; table 2). Excluding one potential outlier27 did not affect this finding.

Table 2.

Long-term effects of CBT compared with pharmacotherapy: ORs of response†

| N | OR | 95% CI | I2‡ | 95% CI | NNT | 95% CI | p§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs continued pharmacotherapy | ||||||||

| All studies | 5 | 1.62 | 0.97 to 2.72 * | 0 | 0 to 79 | 10 | ¶ | |

| One possible outlier excluded†† | 4 | 1.77 | 1.04 to 3.01 | 0 | 0 to 85 | 8 | 4 to 71 | |

| CBT vs discontinued pharmacotherapy | ||||||||

| All studies | 8 | 2.61 | 1.58 to 4.31**** | 0 | 0 to 68 | 5 | 4 to 11 | |

| Three possible outliers excluded‡‡ | 5 | 2.47 | 1.45 to 4.22**** | 0 | 0 to 79 | 6 | 4 to 15 | |

| Subgroups (long-term effects) | ||||||||

| Pharmacotherapy§§ | ||||||||

| SSRI | 2 | 3.02 | 1.29 to 7.04** | 0 | ¶¶ | 5 | 0.82 | |

| TCA | 5 | 2.66 | 1.40 to 5.04*** | 0 | 0 to 79 | 6 | 4 to 15 | |

| Included sample | ||||||||

| All | 2 | 1.97 | 0.91 to 4.27 * | 0 | ¶¶ | 9 | ¶ | 0.14 |

| Responders | 6 | 3.20 | 1.65 to 6.19*** | 0 | 0 to 75 | 4 | 3 to 8 | |

| Quality | ||||||||

| All 4 criteria | 5 | 2.31 | 1.28 to 4.16*** | 0 | 0 to 79 | 6 | 2 to 11 | 0.25 |

| ≤3 criteria | 3 | 3.58 | 1.39 to 9.22*** | 0 | 0 to 90 | 4 | 2 to 10 | |

| Short-term effects | ||||||||

| All the studies | 9 | 1.15 | 0.74 to 1.79 | 53 | 0 to 78 | 20 | ¶ | |

| One possible outlier excluded††† | 8 | 0.96 | 0.72 to 1.30 | 0 | 0 to 68 | ¶ | ||

| Drop out from intervention‡‡‡ | 8 | 0.59 | 0.34 to 0.99** | 48 | 0 to 77 | 9 | 5 to 143 | |

*p<0.1.

**p<0.05.

***p<0.01.

****p<0.001.

†According to the random effects model.

‡In this column, I2 is reported; we also tested whether the Q value was significant. This was the case in two comparisons (indicated with an asterisk*).

§The p value indicates whether the subgroups differ from each other.

¶The 95% CI includes zero and would result in a negative NNT; therefore, we do not report the 95% of the NNT here the 95% CI included zero; because this would result in a negative NNT, we do not report this here.

††Jarrett et al26.

§§One study examined phenelzine (Jarrett et al26); this was not included in the analyses.

¶¶95% CI could not be calculated when degrees of freedom is lower than two.

†††Kovacs et al27.

‡‡‡One study did not report data on drop out (Blackburn et al 21).

CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; NNT, numbers-needed-to-be-treated; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

We also examined whether we could confirm that the drop out from the intervention was significantly higher in pharmacotherapy than in CBT, as has been established in earlier meta-analyses.3 Eight of the nine studies reported sufficient data on drop out to be included in the analyses. We found that the odds of dropping out in the acute phase were significantly lower in CBT than in pharmacotherapy (OR=0.59, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.99). Inspection of the funnel plot indicated that several studies could have been outliers. Because of the small number of studies, however, we did not conduct any additional sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

We found that patients treated acutely with CBT were less likely to relapse following acute treatment termination than patients treated acutely with pharmacotherapy. We did not find that patients treated with acute phase CBT had a significantly lower risk of relapse than patients on pharmacotherapy. There was a non-significant trend (p<0.1) suggesting that relapse rates may be lower after acute phase CBT, but there were too few studies on the long-term effects of CBT and continuation pharmacotherapy to draw definite conclusions. More research is needed before this question can be resolved.

It has been found in earlier research that patients are as likely to respond to CBT as to pharmacotherapy and are less likely to drop out of treatment.3 Moreover, there are indications that the majority of patients who respond to pharmacotherapy do so for non-specific reasons; that is, they show a placebo response and not a ‘true’ drug effect. The same appears to be true for the psychosocial treatments including CBT.31 The fact that CBT results in lower relapse rates than discontinued pharmacotherapy not only suggests that CBT has a specific enduring effect that may operate through somewhat different mechanisms than its acute effects, but also confirms its strong position as a first-line treatment of acute depressive disorders.

The results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution because of a number of limitations. The most important limitation was that small number of studies comparing CBT with continued pharmacotherapy. Also, the number of patients in these studies was relatively small, and the results of the main analyses relied heavily on just a few studies. In such a situation, only a few additional studies with different outcomes can turn these results from a trend to non-significance. Another possible limitation is that there was considerable variation in the methods used between the studies in terms of pharmacotherapy, measures and other characteristics. Also, some studies only included responders to the acute phase in the follow-up analyses, which may have led to bias in the overall results. If high risk patients were more likely to respond to pharmacotherapy than to CBT, then acute treatment could have acted as a ‘differential sieve’ that systematically unbalanced the groups and led to the differential retention of patients differing in an a priori risk being misinterpreted as an enduring effect. Another possible limitation is that the follow-up of the CBT conditions in most of the studies was naturalistic, although some asked patients not to pursue outside treatment in the absence of a documented relapse and censored those events on the few times that they did occur. However, there were important differences between the studies in terms of treatment received during the follow-up phase. There also was considerable variability in when pharmacotherapy was discontinued across the studies, although that should only have led us to underestimate the ‘true’ magnitude of the advantage for acute phase CBT in that comparison. Moreover, the quality of the studies included in this meta-analysis was high, and even if the next ten studies all produced an advantage for ongoing continued pharmacotherapy, acute phase CBT would still be as efficacious as continuation pharmacotherapy. Subsequent replication is needed before a possible superiority of acute phase CBT over continuation pharmacotherapy can be taken seriously, but the possibility is of sufficient importance that such efforts clearly should be made.

Studies on the long-term effects of treatments of depression are complicated, because subsequent treatment is difficult to control (but not impossible to influence). Another complication is that patients both need to complete and respond to acute treatment in order to be at risk for subsequent relapse or recurrence; large numbers of patients need to be randomised initially to differential treatment in order to have enough patients remit to detect anything but the largest subsequent differences during follow-up. Furthermore, acute and continuation/maintenance treatments can be offered in several varieties and the latter can be changed during the course of the follow-up. The number of possible comparisons is therefore large, but all are needed to give an adequate answer to the question which treatment is the best for the longer term. The most important design for a future study, however, would be a sufficiently powered trial comparing acute phase CBT without subsequent continuation versus acute phase pharmacotherapy with subsequent continuation (the current standard of treatment). Although some studies have used this design, none had sufficient statistical power to find significant differences of the magnitude (modest but clinically relevant) between the two suggested by this meta-analysis. It seems highly relevant to conduct such a trial.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PC and SDH had the idea for this study. PC drafted the initial manuscript, prepared and cleaned the data and conducted the data analysis. SDH, AVS, CB, MB and GA read all the versions of the manuscript critically and contributed to the final approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R, et al. A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson KS, Berking M, Andersson G, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavior therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison to other treatments. Can J Psychiatry, submitted [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavior therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison to other treatments. Can J Psychiat 2013. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollon SD, Stewart MO, Strunk D. Cognitive behavior therapy has enduring effects in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Annu Rev Psychol 2006;57:285–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollon SD, Thase ME, Markowitz JC. Treatment and prevention of depression. Psychol Sci Public Interest 2002;3:39–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edn Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:851–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, et al. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression, a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy's effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:475–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Psychological treatment of depression: a meta-analytic database of randomized studies. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck AT, Rush J, Shaw B, et al. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Characteristics of effective psychological treatments of depression; a meta-regression analysis. Psychother Res 2008;18:225–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1728–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ioannidis JPA, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ 2007;335:914–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orsini N, Higgins J, Bottai M, et al. Heterogi: Stata module to quantify heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. (http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s449201). (accessed 27 Feb 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, et al. Assessing publication bias in meta-analyses in the presence of between-study heterogeneity. J R Stat Soc 2010;173:575–91 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenthal R. The ‘file drawer problem’ and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 1986;86:638–41 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackburn IM, Eunson KM, Bishop S. Two-year naturalistic follow-up of depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy, pharmacotherapy and a combination of both. J Affect Dis 1986;10:67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David D, Szentagotai A, Lupu V, et al. Rational emotive behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial, posttreatment outcomes, and six month follow-up. J Clin Psychol 2008;64:728–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobson KS, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:468–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans MD, Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, et al. Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen psychiatry 1992;49:802–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy versus medication in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:417–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarrett RB, Kraft D, Schaffer M, et al. Reducing relapse in depressed outpatients with atypical features: a pilot study. Psychother Psychosom 2000;69:232–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovacs M, Rush J, Beck AT, et al. Depressed outpatients treated with cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:33–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shea MT, Elkin I, Imber SD, et al. Course of depressive symptoms over follow-up. Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:782–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons AD, Murphy GE, Levine JL, et al. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, et al. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med 2010;40:1943–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driessen E, Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, et al. Does pretreatment severity moderate the efficacy of psychological treatment of adult outpatient depression? A meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010;78:668–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.