Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the hypothesis that junior doctors’ examination skills are deteriorating by assessing the medical admission note examination record.

Design

Retrospective study of the admission record.

Setting

Tertiary care hospital.

Methods

The admission records of 266 patients admitted to Wellington hospital between 1975 and 2011 were analysed, according to the total number of physical examination observations (PEOtot), examination of the relevant system pertaining to the presenting complaint (RelSystem) and the number of body systems examined (Nsystems). Subgroup analysis proceeded according to admission year, level of experience of the admitting doctor (registrar, house surgeon (HS) and trainee intern (TI)) and medical versus surgical admission notes. Further analysis investigated the trend over time in documentation with respect to cardiac murmurs, palpable liver, palpable spleen, carotid bruit, heart rate, funduscopy and apex beat location and character.

Results

PEOtot declined by 34% from 1975 to 2011. Surgical admission notes had 21% fewer observations than medical notes. RelSystem occurred in 94% of admissions, with no decline over time. Medical notes documented this more frequently than surgical notes (98% and 86%, respectively). There were no differences between registrars and HS, except for the 2010s subgroup (97% and 65%, respectively). Nsystems declined over the study period. Medical admission notes documented more body systems than surgical notes. There were no differences between registrars, HSs and TIs. Fewer examinations were performed for palpable liver, palpable spleen, cardiac murmur and apex beat location and character over the study period. There was no temporal change in the positive findings of these observations or heart rate rounding.

Conclusions

There has been a decline in the admission record at Wellington hospital between 1975 and 2011, implying a deterioration in local doctors’ physical examination skills. Measures to counter this trend are discussed.

Keywords: Medical education & training, Medical students, Surgery

Article summary.

Article focus

There is well-documented international evidence supporting a declining standard in junior doctors’ physical examination skills in recent years.

This study was conducted to address the research question that this deterioration has occurred locally in Wellington, New Zealand.

Key messages

There has been a decline in the quantity and quality of the medical admission note examination records in this tertiary care centre between 1975 and 2011, which implies a decline in the examination skills of local junior doctors.

The total number of physical examination observations and number of body systems examined declined over the study period, and fewer examinations were performed for palpable liver, palpable spleen, cardiac murmur and apex beat location and character.

Measures to address this decay in clinical ability include improved undergraduate curriculum, greater supervision of junior doctors, greater involvement of junior doctors in the admission process and increased staffing levels.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a significant study involving large numbers of patient admission records over a substantial period of time (358 patient records over four decades) with a multitude of statistically robust outcome measures analysed.

Our study is limited due to its retrospective nature, single-centre study, the use of the ‘surrogate’ marker of the written medical record to reflect clinical examination skills, and the confusing admission process, whereby doctors will see a patient but not necessarily “admit” them. In addition, the data were extracted by only one researcher.

Introduction

Thoughtful history taking and physical examination are recognised as fundamental to the practice of medicine.1 Moreover, physicians rate physical examination as their most valuable skill.2 It has also been shown that despite the current technology, physical examination remains important due to its diagnostic contribution,3 positive effect on patient care4 and cost reduction.5

There has been a well-recognised international decline in the physical examination skills of doctors. Potential reasons for this deterioration include busy clinical workloads and lack of clinical teaching.6 7 However, it is generally recognised that the most important influence has been the increased availability of specialised diagnostic equipment.8 9 Imaging technology such as ultrasound, CT and MRI have overshadowed the use of physical examination for diagnostic information.8 9 Although adding enormously to the cost of healthcare, these investigations are seen to be more accurate and less liable to litigation, than the more subjective art of physical examination.8 9 It has been argued that the overuse of this technology has also helped to erode the teaching and skill in physical diagnosis8 10 and that it may be undermining the value of these skills.4 This is further impacted by the shift away from bedside teaching and supervision of physical examination skills during undergraduate years and early years of practice.6 10 11 In the USA bedside teaching has fallen from 75% of clinical teaching in the 1960s10 to 8–19% of clinical teaching in 2008.12 Thus there are significant changes required from both the medical school and hospital culture regarding physical examination skill acquisition, improvement and retention.

The medical record is a tool for communication between multiple health professionals, facilitating continuity of care and good patient management.13 There have been a number of studies referencing the importance of the quality of the medical record.14–19 The medical record is also a legal document and as such deserves the appropriate time and attention to ensure it is ‘comprehensive and accurate’.13 Some studies have looked into ways to improve documentation such as introducing a clinical note header section,20 education and instruction21 22 and structured encounter forms23 with positive results. There are currently no evidence-based standards for best practice concerning adequacy of documentation of physical examination findings for Wellington Hospital, neither are there any clinical guidelines derived from expert opinion. Thus it is difficult to ascertain the expected minimum level of documentation. In order to retrospectively investigate examination practice over time we are reliant on this medical record for our information. The current study is inevitably an investigation into both the skills of doctors and their documentation practices, although our primary hypothesis is that there has been a decline in the standards of junior doctors’ physical examination skills.

Methods

This retrospective study looked at admission records from patients admitted to Capital and Coast District Health Board (Wellington and Kenepuru Hospitals) between 1975 and 2010. The records were randomly selected by National Health Index (NHI) number if the patient had been admitted during this time with certain medical diagnoses, as reflected by the ‘coding diagnosis’ which enables clerical staff to enter the correct computer information about each admission. The year 1998 was the earliest year for which we could get a random NHI list generated. In this way we obtained 300 sets of patient admission records, 100 from 1998, 100 from 2000 and 100 from 2010, from the medical records department at Wellington Hospital. Out of each set of 100 records there were 50 general medical and 50 surgical admissions. The medical coding diagnoses were pneumonia, congestive heart failure, shortness of breath or chest pain. The surgical coding diagnoses were inguinal hernia, appendicitis, abdominal pain, fractured neck of femur or bowel obstruction. Many of these medical files included records from previous admissions to hospital. We included these older admission notes if they had been coded with the aforementioned diagnoses, and if there was at least 10 years temporal separation from the randomly selected admission and we used only one older admission per patient. Strict patient and staff confidentiality was maintained at all times.

The admission note from each record was examined and the relevant data were extracted by one researcher, the primary author, with verification and close supervision by two other researchers (the corresponding and final authors). This data were entered into a predeveloped spreadsheet. If there was no admission note, we examined the last documented examination in the emergency department before ward admission. This was generally performed by the registrar of the admitting ward. The data from this examination were then entered as stated previously.

We recorded the total number of physical examination observations (PEOtot) that were documented per admission. We also documented the number of major body systems that had been examined (Nsystems). These were defined as the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory and central nervous systems. We then noted whether the relevant system pertaining to the presenting complaint had been examined (RelSystem). We then analysed the data in terms of year groups, in order to look for temporal change.

We subsequently analysed the data according to whether it was a medical or surgical admission note, and the level of experience of the admitting doctor (registrars, house surgeons (HS) or trainee interns (TI)) with respect to PEOtot, Nsystems and RelSystem. We also performed year group analysis on these subgroups.

We also investigated whether there was documentation of particular examination observations, positive or negative. These were palpable liver, palpable spleen, carotid bruit, cardiac murmur, apex beat location and character and funduscopy. We analysed whether the frequency of these documented observations changed over time. Of the admission notes documenting the performance of these examinations, we then examined the frequency of positive findings and any change over time.

Finally we investigated the documentation of heart rate. Of those admission notes with a heart rate value, we analysed the frequency with which the heart rate was given as a value perfectly divisible by five, suggesting a tendency of the admitting doctor towards rounding the actual value and thus potential inaccuracy. We then examined for a change in this trend over time.

Results

We examined 358 patient admission records, from 266 patients admitted to Capital and Coast District Health Board (Wellington and Kenepuru Hospitals) between 1975 and 2010. For administrative reasons we were unable to obtain 34 of the ordered sets of notes. There was no statistically significant difference in the patients’ age between the year groups, after Kruskal-Wallis analysis. A biostatistician performed all analyses.

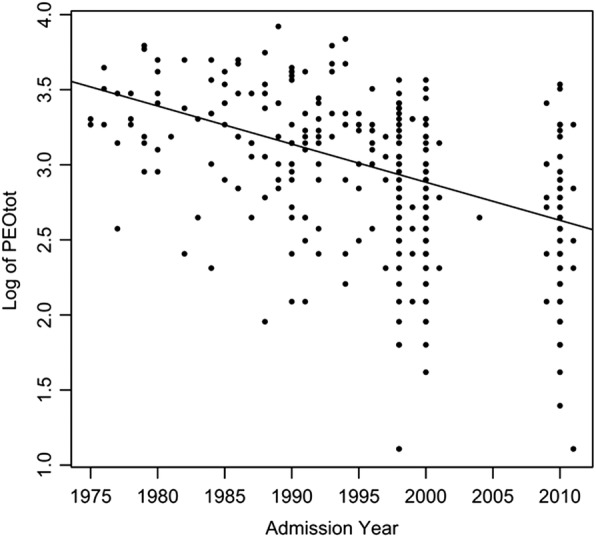

As evidenced by the documentation in the hospital record admission notes, there has been a statistically significant decrease (34%) in the PEOtot per admission from 1975 to 2011 (p<0.001; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total number of physical examinations observations per admission versus time.

There were significantly fewer (21%) total observations in surgical admission notes, compared with medical admission notes (p<0.001). Registrars recorded 12% fewer total observations compared with HSs (p<0.001). Statistical significance with respect to admission year group, specialty and level of experience of the admitting doctor in terms of predicting PEOtot was achieved by using the Wald χ² test. PEOtot was analysed as a negative binomial regression model (overdispersed data) by rendering the ‘admission year’ as a continuous variable and the ‘admission ward’ and ‘doctor level of experience’ as categorical variables.

With respect to the examination of the RelSystem, we have found that this occurred in 94% of all admission notes (95% CI) and there was no statistically significant change over time (p<0.1). There was, however, a significant difference according to specialty, with surgical doctors less likely to have examined RelSystem compared with their medical counterparts (86% vs 98%, respectively, p<0.001). Further subanalysis of specialty and RelSystem with respect to year group showed no statistically significant differences except for the 2010s, in which 25% of surgical admissions did not record examination of the relevant system compared with 3% of medical admissions (p<0.05); (pre 1990s (p>0.05), 1990s (p<0.1) 2000s (p<0.1)).

There was no statistically significant difference overall between examination of the relevant system pertaining to their presenting complaint (RelSystem) with respect to level of experience of admitting doctor (registrar, HS and TI; p<0.01). Further analysis by year groups shows a difference only for the 2010s, in which registrars documented RelSystem in 97% of admissions compared with 65% of HSs (p<0.005).

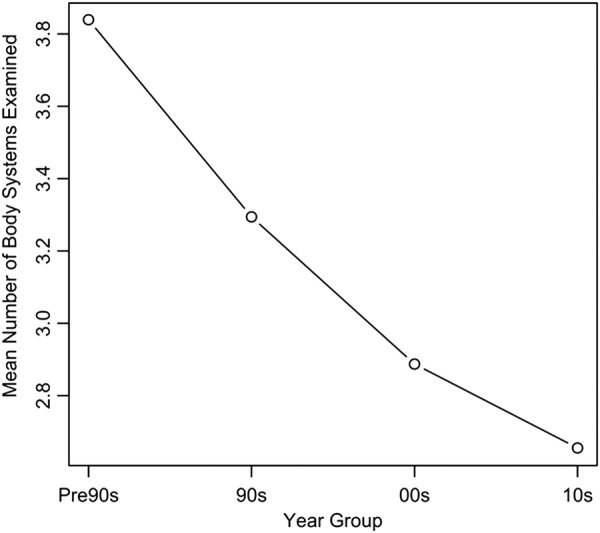

The total number of body systems examined (Nsystems) significantly declined over the study period, with a change of 1.184 mean body systems (p<0.001;figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean number of body systems examined per year group.

The most commonly omitted body system was the central nervous system, across all the year groups.

There was a significant difference according to specialty between medical and surgical admissions, with surgical doctors examining less Nsystems than physicians (p<0.01). There were no significant differences between specialty within each of the year groups (p<0.1). With respect to the level of experience of the admitting doctor, there were no significant differences in Nsystems (p>0.5) or within year groups (p<0.1).

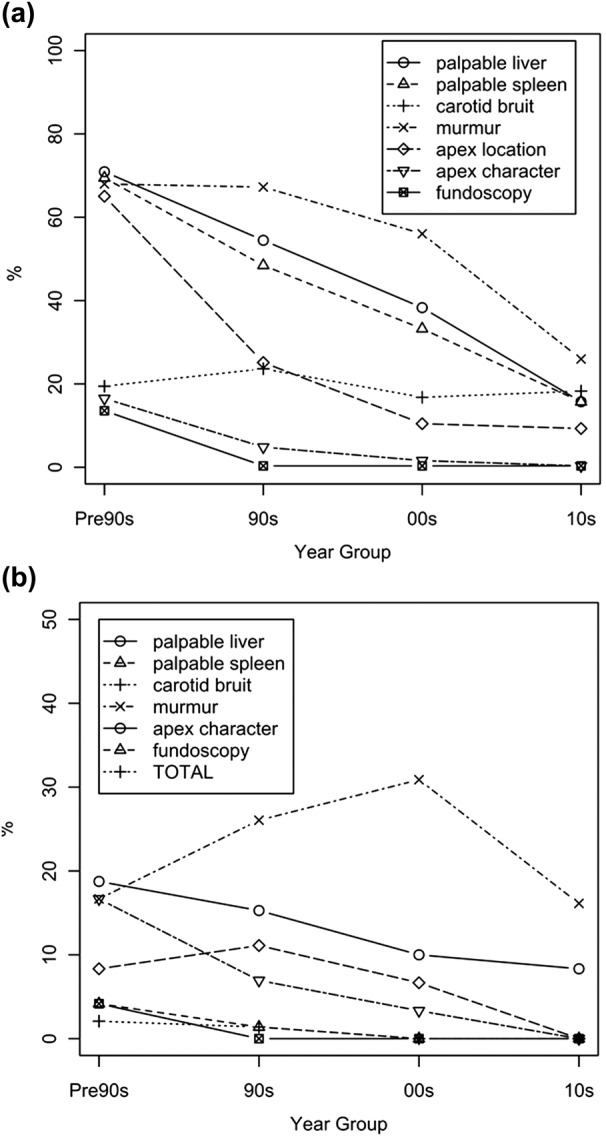

There was a significant decline over the study period in the percentage of admission notes with recorded examinations for palpable liver, palpable spleen, cardiac murmur and apex beat location and character (χ²=51.3, 47.8, 32.0 and 57.9, respectively, df=1, p<0.001). Statistical analysis was performed by Cochran-Armitage testing, and 95% CIs were used. There was no significant change in the frequency of recorded examinations for carotid bruits (χ²=0.4, df=1, p>0.5). There was no year group analysis performed for funduscopy, as this was only documented in the pre 90-year group (figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Percentage of admission notes with recorded examinations for palpable liver, palpable spleen, carotid bruit, murmur, apex location, apex character and funduscopy versus year group. (B) Percentage of admission notes with positive findings for palpable liver, palpable spleen, carotid bruit, murmur, apex location, apex character and funduscopy versus year group.

There were no changes over time with respect to positive cardiac murmur, palpable liver, palpable spleen, carotid bruit and apex beat location and character (χ²=0.01, df=1, p>0.5 for cardiac murmur; χ²=1.5, 1.8, 1.7, 0.2 and 0.5 respectively, df=1, p>0.5 for the rest). This is probably due to the low frequency of positive findings within each of the year groups. Statistical analysis was performed by Cochran-Armitage testing, and 95% CIs were used (figure 3B).

We found that the vast majority of admission notes documented heart rate, with approximately 50% in each year group documenting a heart rate divisible by five and no change over time with respect to the latter (χ²=0.8, df=1, p>0.5). Statistical analysis was provided by Cochran-Armitage testing, and 95% CIs were used.

Discussion

Our results imply that there has been deterioration in the physical examination skills of junior doctors in Wellington Hospital from 1975 to 2010, after detailed analysis of the medical admission record notes. This is evident from the observed decline in the recorded PEOtot, total number of body systems examined and the number of recorded observations for palpable liver, palpable spleen, cardiac murmur and apex beat location and character. In the author's opinion, this temporal deterioration could be due to the increased use and availability of complex diagnostic technology8 9 as well as the concurrent loss of confidence in physical examination skills. Busy workloads may necessitate substandard physical examinations and the resulting documentation. Low examination skill proficiency after initial training, and little opportunity to improve these skills6 7 and the resultant effect on student and teacher confidence further contribute to the demise of clinical examination. Recent anecdotal comments from undergraduate students attached to surgical wards at Wellington Hospital suggest that junior staff transmit a negative view towards the value of physical examination skills, thus creating a ‘cyclic’ phenomenom of further medical deskilling with each year of medical graduates.

Interestingly there has been no general decline in the examination of the RelSystem. It could be argued that the latter constitutes the ‘bare minimum’, and hence has suffered less than the other parts of the medical admission record.

We found that registrars recorded 12% fewer total observations than HSs. In the authors’ opinion, this could be a reflection of the local admission process, for both medical and surgical patients. For many years, it has been the convention in Wellington that registrars assess and diagnose the patient before instigating appropriate initial therapy. Then the team HS is called to complete the ‘clerking’ process—that is, complete the history and examination of the admission, chart the patients’ medications and fluids, etc. This is also the case for elective patients undergoing the preassesment process before their scheduled surgery, where the initial documentation of the patient’s medical problems is performed by an anaesthetist before the HS interviews the patient. This may not reflect practice in all New Zealand or international hospitals.

It remains unclear why surgical admission notes contain less total observations and number of body systems than their medical counterparts. In the authors’ opinion, physicians may arguably take a more holistic approach to their patients, and are hence more likely to examine more body systems and document a greater number of examination findings. The differential diagnoses of medical complaints may be broader than surgical complaints, warranting such a detailed assessment. Junior surgical staff are frequently time pressured as they are often on call for acute assessments, as well as being expected to be in the operating theatre. Surgical house officers are the only staff available to deal with the often complex medical issues in the surgical ward. If this time pressure is indeed a true factor in the declining standards of the surgical admission note, greater surgical staffing resources could ameliorate this situation. Other measures that may help reduce the workload include the involvement of senior medical staff early in the admission process in managing complex medical problems. This is already occurring in some wards, with Consultant Geriatricians seeing elderly orthopaedic patients with hip fractures soon after admission. Certainly there is consensus regarding the benefits resulting from the routine involvement of an elderly care physician in such circumstances.24 Many studies have shown shorter hospital stays, reduced mortality, improved placement on discharge although there is conflicting evidence regarding cost-savings.24 While this approach may indeed benefit hospitals and orthogeriatric patients, it may result in further clinical deskilling of junior doctors.

Surgical admission notes contained less examination of the relevant system pertaining to the presenting complaint compared with medical admission notes. This was especially true in the 2010-year group. In the authors’ opinion, this could be again due to the surgical admission process, whereby the surgical registrar assesses the patient (and presumably examines the relevant system) but does not actually complete a full admission note, which is then completed by the surgical house officer. Anecdotal experience shows that in recent years, junior staff, completing the admission note. often do not feel it is necessary to repeat the examination of the relevant system, especially as further examination of a tender abdomen or fractured limb can cause discomfort. This is borne out by the subgroup analysis finding showing that in the 2010-year group the registrars documented RelSystem in 97% of admissions, compared with 65% of HSs.

There were several limitations to our study. These include its retrospective nature, the use of the ‘surrogate’ marker of the medical record to reflect clinical examination skills, and the confusing admission process, whereby doctors will see a patient but not necessarily ‘admit’ them. In addition, database restrictions in the medical records department meant we were only able to request medical admission files from 1998 onwards. The study could have had greater statistical impact if we were able to access large numbers of records from much earlier. We were able to obtain some earlier admission notes, when these were co-filed with more contemporary records, although these were not randomly selected. However, these earlier notes were at least 10 years apart from the other records, there was only one older file per patient, and statistical analysis showed no difference in patient age across the year groups. This was single-centre study hence further research is warranted at other national and international hospitals. Finally, our data were extracted by only one researcher, the first author, however, this was closely supervised and verified by two other researchers.

This is the second study from Wellington Hospital that has identified the declining quality of the hospital admission note with regard to physical examination. A previous Wellington study concluded that there has been a decline in the quality of the surgical HS admission note (SHSurgAdN) when comparing 2005 and 2009 (Morgan TG, Dennet ER. Quality of House Surgeon Acute Surgical Admissions, 2005 vs 2009 (personal communication)). The authors found that the SHSurgAdN was comparatively deficient in the documentation of the relevant system examination and the cardiorespiratory examination, and that this deficiency had worsened over the intervening 4 years. This study faced similar limitations as the current study, that is, it was single-centred, retrospective, the admission note was used as a surrogate for the assessment of the junior doctors’ physical examination skills, and the admission process is complicated. However, it was well designed and had good power, with 100 admission notes audited in total. This study differed from the current study in that it incorporated a HS questionnaire, with questions on history taking as well as clinical examination. The current study involves the investigation of an even greater number of admissions over a longer time period, with more extracted data.

There are potential solutions to halt this decline in physical examination skills. Some local barriers to clinical competence have been identified and ways to improve this deficit have been suggested.7 In the authors’ opinion, these could include increased senior supervision of the admitting process including formative feedback and reflection, as well as a local cultural change enabling HSs to initially assess patients while senior staff provide supervision and guidance. This would require increased junior staffing or work-based changes to address workload issues, as well as commitment from senior colleagues to ensure that there is no compromise to patient safety. Finally, international evidence suggests that improved undergraduate curriculum especially bedside teaching and enhanced supervision of new doctors could redirect the current downward trend in physical examination.6 8 10 11

During the audit process in this study, there was also significant variation in the history component of the admission note. History is a vital part of the admission process, and is crucial to diagnostic success.25 26 Further research is warranted regarding the adequacy of history taking as evidenced by the admission record.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Michael Harrison for his advice and help in revision of the paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors listed have made significant contributions to this paper. CMO was involved in the extraction and processing of the data, data analysis and interpretation, literature search, discussion points and initial draft formation. SAH was not only involved in an administrative and communication capacity but has contributed significantly with respect to study design, data extraction and analysis, interpretation and statistical analysis, literature search and final paper revisions. TI was responsible for the statistical analysis and figures. DCG designed the study and was involved in the extraction of the data, interpretation of the data and critical review of the publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The original project was funded by the Research Office in the University of Otago Wellington.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Li J. Clinical skills in the 21st century. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kern DC, Parrinog TA, Korst DR. The lasting value of clinical skills. J Am Med Assoc 1985;254:70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lembo NJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Crawford MH, et al. Bedside diagnosis of systolic murmurs. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1572–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly B. Physical examination in the care of medical inpatients: an observational study. Lancet 2003;362:1100–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaver JA. Cardiac auscultation: a cost-effective diagnostic skill. Curr Probl Cardiol 1995;20:441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan-Yan C, Gillies JH, Ruedy J, et al. Clinical skills of medical residents: a review of physical examination. CMAJ 1988;139:629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheehan D, Wilkinson TJ, Billett S. Interns’ participation and learning in clinical environments in a New Zealand hospital. Acad Med 2005;80:302–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangione S, Peitzman S. Physical diagnosis in the 1990s. Art or artifact? J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:490–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tavel M. Cardiac auscultation: a glorious past—but does it have a future? Circulation 1996;93:1250–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaCombe MA. On bedside teaching. Ann Int Med 1997;126:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med 2009;4:304–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams KN, Ramani S, Fraser B, et al. Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group of study learners. Acad Med 2008;83:257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.2011. Cole's Medical Practice in New Zealand. Wellington Medical Council of New Zealand.

- 14.Baker MD, Schoenfeld PS. Documentation in the pediatric emergency department: a review of resuscitation cases. Ann Emerg Med 1991;20:641–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox JL, Zitner D, Courtney KD, et al. Undocumented patient information: an impediment to quality of care. Am J Med 2003;114:211–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunlay SMMD, Alexander KPMD, Melloni CMD, et al. Medical records and quality of care in acute coronary syndromes: results from CRUSADE. Arch Inter Med 2008;168:1692–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hicks TA, Gentleman CA. Improving physician documentation through a clinical documentation management program. Nurs Adm Q 2003;27:285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liesenfeld B, Heekeren H, Schade G, et al. Quality of documentation in medical reports of diabetic patients. Int J Qual Health Care 1996;8:537–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller JM, Velanovich V. The natural language of the surgeon's clinical note in outcomes assessment: a qualitative analysis of the medical record. Am J Surg 2010;199:817–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denny JC, Miller RA, Johnson KB, et al. Development and evaluation of a clinical note section header terminology [Evaluation Studies Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.]. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2008:156–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinsley JA. An educational intervention to improve residents’ inpatient charting. Acad Psychiatry 2004;28:136–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JJ, Bland SA, Mullett S. Temperature—the forgotten vital sign [Evaluation studies]. Accid Emerg Nurs 2005;13:247–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanegaye JT, Cheng JC, McCaslin RI, et al. Improved documentation of wound care with a structured encounter form in the pediatric emergency department [Evaluation Studies]. Ambul Pediatr 2005;5:253–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan R, Fernandez C, Kashig F, et al. Combined orthogeriatric care in the management of hip fractures: a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2002;84:122–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson MC, Holbrook JH, Hales D. Contributions of the history, physical examination and laboratory investigation in making medical diagnoses. Br Med J 1992;156:163–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hampton JR, Harrison MJG,, Mitchell JRA. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. BMJ 1975;2:486–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.