Abstract

Objective

To summarise how costs and health benefits will change with the adoption of total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared to total abdominal hysterectomy for the treatment of early stage endometrial cancer.

Design

Cost-effectiveness modelling using the information from a randomised controlled trial.

Participants

Two hypothetical modelled cohorts of 1000 individuals undergoing total laparoscopic hysterectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy.

Outcome measures

Surgery costs; hospital bed days used; total healthcare costs; quality-adjusted life years; and net monetary benefits.

Results

For 1000 individuals receiving total laparoscopic hysterectomy surgery, the costs were $509 575 higher, 3548 hospital fewer bed days were used and total health services costs were reduced by $3 746 221. There were 39.13 more quality-adjusted life years for a 5 year period following surgery.

Conclusions

The adoption of total laparoscopic hysterectomy is almost certainly a good decision for health services policy makers. There is 100% probability that it will be cost saving to health services, a 86.8% probability that it will increase health benefits and a 99.5% chance that it returns net monetary benefits greater than zero.

Keywords: Health economics

Article summary.

Article focus

To evaluate how costs and health benefits change with the adoption of laproscopic surgery rather than using laparotomy to treat endometrial cancer.

Key messages

Surgery costs are higher for laproscopic surgery.

Length of stay in hospital and overall health services costs are lower for laproscopic surgery.

Health benefits measured by quality-adjusted life years are higher for laproscopic surgery.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Lower cost and better health outcomes are a ‘win win’ for health services.

The conclusions are easy to interpret for health policy makers.

Mortality data were used from a study carried out in a different jurisdiction.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynaecological cancer accounting for 300 000 new diagnoses worldwide.1 In developed countries, lifetime risk is between 2.5% and 3% and incidence is rising.2 3 Risk factors include increasing age, obesity, diabetes mellitus, nulliparity, late menopause, unopposed oestrogen intake or oestrogen producing tumours, a history of breast cancer and use of tamoxifen.4 5 Standard treatment is surgery to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. In selected patients, retroperitoneal pelvic and/or aortic lymph nodes are removed to establish the extent of the cancer and assist in ongoing treatment choices. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) has been proposed as an alternative to total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) widely used by gynaecological cancer surgeons and has been tested in three randomised trials worldwide. Patients who had TLH instead of TAH for uterine cancer had better postsurgical quality of life (QoL), fewer complications and shorter hospital stay.6–8 One study did show an incidence of major and minor surgical complications as similar in patients undergoing a TLH or TAH.9 The aim of the research reported here is to identify how costs and health benefits will change with the adoption of TLH over TAH through laparotomy for the treatment of early stage endometrial cancer. A health services perspective is adopted and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) estimated. Information for this modelling study was available from the LACE trial.10

Method

Randomised controlled trial

The LACE trial is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00096408) and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (CTRN12606000261516) and was approved by all relevant hospital and university human research ethics committees. A detailed description of the study including details of the two surgical approaches has been published previously.6 10 Between October 2005 and June 2010, 760 patients were recruited through 1 of the 20 participating tertiary gynaecological oncology centres in Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong and Scotland. Women were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older, with histologically confirmed endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium of any FIGO grade, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of less than 2. Further inclusion criteria included imaging studies suggesting the absence of extra-uterine disease. Patients were excluded from the study if any of the following criteria were met: histological cell-type other than endometrioid on curettage, clinically advanced disease (stage II–IV) or bulky lymph nodes on imaging, uterine size greater than 10 weeks of gestation, estimated life expectancy of less than 6 months, medically unfit for surgery, patient compliance or geographic proximity preventing adequate follow-up or unfit to complete QoL questionnaires. The FIGO criteria for stage (2009) were used. Randomisation using stratified permuted blocks was carried out centrally and independent from other study procedures through a web-based system at the University of Queensland. Randomisation was stratified according to treating centre and by grade of differentiation as taken from the endometrial biopsy/D&C.6 10 All surgeons on the trial had to be accredited by the trial management committee before being eligible to enrol patients. After informed consent was obtained, trial staff checked eligibility and received notification of the allocated treatment via the web-based case report system. Blinding was not possible due to ethical considerations and the nature of the treatment.

Primary outcomes from the LACE trial have been published6 11 and show the TLH and TAH groups were similar according to clinical and demographic factors and the incidence of intra-operative adverse events were comparable. The incidence of postoperative adverse events and serious adverse events was significantly higher in the TAH group compared to the TLH group. There were differences in the rates of lymph node dissection with 60.2% in the TAH group and 39.9% in the TLH group and this may influence adverse events and costs and the QoL outcomes. The average operating time was higher for TLH (132 min) as compared to TAH (107 min), but the median length of stay was lower for TLH (2 days) as compared to TAH (5 days). QoL outcomes were published for a subset of the participants and it show that in the early phase of recovery the TLH group had better QoL from baseline compared to the TAH group in all subscales of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) V.4, except for emotional and social wellbeing. Some QoL advantages were still present up to 6 months after surgery.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A two-state Markov model was used to predict how a generalised population of patients transitioned into a state of DEAD from ALIVE for a modelled cohort of 1000 TAH and TLH patients during the 1825 days or 5 years postsurgery. Daily risks of death were estimated for either arm of the trial and applied to the two cohorts based on survival data reported by Walker et al.12 This was a separate study of mortality risk from laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer and it revealed 5-year survival of 89.8% for patients randomly assigned to laparoscopy and 89.8% for patients randomly assigned to laparotomy. For each day of the model, a utility score was assigned to those in the ALIVE state based on the individual EQ-5D tariffs reported from trial participants. Values were collected presurgery and 1 week, 4 weeks, 3 months and 6 months postsurgery. The 6-month value was used for all days from 6 to 12 months. After 12 months, it was assumed that the QoL was similar for both groups and a mean score was used until day 1825. Health benefits arising in future time periods were discounted at 3% in line with recent guidelines. The costs of the two surgical treatments included theatre nursing costs, allocated by duration of procedure; all equipment and consumables used; and Medicare Benefits Schedule13 items for surgical and anaesthetics fees for abdominal and laparoscopic procedures. The costs of health services used in the 6 months following surgery were consultations with doctors other than gynaecology oncology; psychiatrist, psychologist or other mental health counsellors; nurse practitioner; home health nurse and physical/occupational or respiratory therapist; and consultations as an outpatient and visits to the emergency department. The number of days in hospital recovering from the initial surgical treatment and any subsequent admissions during the 6 months after treatment were aggregated and valued by a national hospital pricing model14; these prices were adjusted to 2011 values based on 3% annual price inflation. All costs were valued in Australian dollars at 2011 prices, health benefits represented by QALYs and the marginal QALY was given a monetary value of $64 000.15 Net monetary benefits were estimated by multiplying each QALY gained by $64 000 and then deducting the change to costs. Uncertainty among the model parameters was included by fitting the individual data to probability distributions. The β-distribution was used for transition probabilities and utility scores, and the γ-distribution was used for the costs.16 One thousand random samples were taken from the prior distributions to reveal the joint distribution of cost and QALY outcomes for patients in both arms of the trial.

Because of different rates of lymph node dissection among the two groups, an alternate version of the model that excluded all patients with lymph node dissection was also evaluated. This scenario analysis will assess the sensitivity of the conclusions to any bias on outcomes arising from the differences in rates of lymph node dissection.

Results

The mean and SD for the EQ-5D scores for TAH and TLH for 1 week, 4 weeks, 3 months and 6 months postsurgery are shown in table 1. The difference in QoL outcomes is modest, but is the largest in 1 week postsurgery and then reduces over time.

Table 1.

EQ-5D scores from all trial participants

| TAH (mean (SD)) | TLH (Mean (SD)) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 week | 0.63 (0.24) | 0.71 (0.23) |

| 4 weeks | 0.79 (0.22) | 0.84 (0.19) |

| 3 months | 0.82 (0.25) | 0.86 (0.22) |

| 6 months | 0.82 (0.27) | 0.86 (0.23) |

TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; TLH, total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

The costs of theatre time, equipment and consumables were provided by the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital and were $1734.49 for a TLH case and $957.42 for a TAH case. Medicare Benefits Schedule item numbers (http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/) were used to estimate the costs of surgeon and anaesthetists time and in total were $5610 for TLH and $5460 for TAH. Nursing costs of $46.22/h were used to reflect a Grade 6 Nurse and it was assumed that 2.5 nurses are required to support either a TLH or TAH. The duration of each surgery was used to estimate nursing costs per case. One hour of nursing time was added for preparation and clean up. Medicare Benefits Schedule item numbers were also used to value the subsequent use of consultations with GPs ($120.3), consultations with psychiatrist, psychologist or other mental health counsellors ($249.3), visits to the emergency department ($200.95), short consultations with nurse practitioner, home health nurse, physical/occupational or respiratory therapist ($22.7) and visits to a hospital out-patient department ($200.95). The cost of a night in a hospital bed was valued at $1133; this was derived by adjusting estimates published by Australian Institute of Health & Welfare to 2011 prices.14

The most useful results from the modelling that compared TLH with TAH are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Results from cost-effectiveness model

| TAH (mean (SD)) | TLH (mean (SD)) | Difference per patient | Difference for 1000 patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery costs ($) | 6755 (4.76) | 7265 (3.93) | 510 | 509575.37 |

| Bed days used* | 7.31 (0.52) | 3.76 (0.24) | −3.55 | −3548.18 |

| Total costs ($)† | 15870 (637) | 12124 (311) | −3746 | −3746221.69 |

| QALYs‡ | 3.42 (0.046) | 3.46 (0.039) | 0.04 | 39.13 |

*For the recovery from surgery and for subsequent admissions within 6 months.

†This includes all health services used from surgery to 6 months after.

‡For the 1825 days described by the model.

TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; TLH, total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

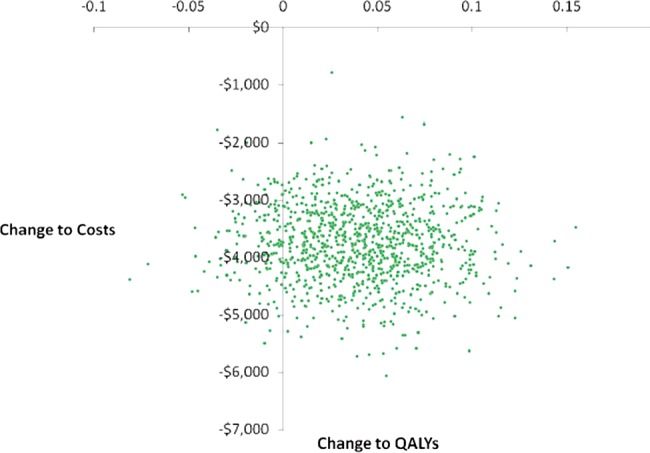

On average, the higher surgery costs of TLH over TAH are compensated by cost savings in health services that accrue in the 6 months after surgery. In particular 3.55 hospital bed days are saved for each patient who has TLH, and there are extrahealth benefits of 0.04 QALYs that accrue during the 1825 days of model duration. The uncertainty in the data is shown by figure 1, which illustrates the joint distribution of change to costs and health benefits from a decision to adopt TLH over TAH. The distributions of the total cost and QALY outcomes are shown in online supplementary appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Joint distribution of change to costs and health benefits from a decision to adopt total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) over total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH).

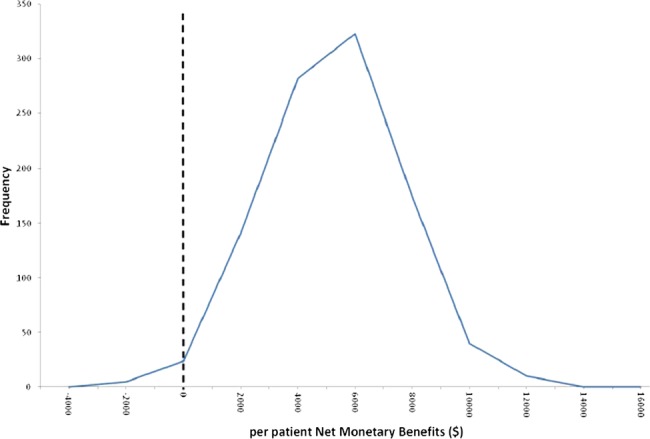

The adoption of TLH over TAH will always save costs and there is 86.8% probability that health benefits will be increased, which means a high chance of health services enjoying a ‘win win’. The distribution of the net monetary benefit of a decision to adopt TLH over TAH is shown in figure 2 and there is a 99.5% probability that the net monetary benefit from adoption TLH over TAH will be greater than zero. The area to the left of the dashed line at zero in figure 2 is 0.05% of the area under this curve.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the net monetary benefit of a decision to adopt adopt total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) over total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH).

Model results did change when the patients with lymph-node dissection were excluded: the difference in surgery costs fell from $510 to $482, the savings in lengths of stay fell from 3.55 to 3.38, total cost savings fell from $3746 to $3734 and QALY gains were reduced from 0.04 to 0.03. Under this scenario, the adoption of TLH over TAH will again always save costs and there is 79.8% probability that health benefits will be increased. There is a 98.3% probability that the net monetary benefit from adoption TLH over TAH will be greater than zero, providing strong evidence that adoption is a good decision.

Discussion

Based on the data, we have used the adoption of TLH which is almost certainly a good decision for health services policy makers. There is 100% probability that it will be cost saving to health services, a 86.8% probability that it will increase health benefits, although the QoL benefits are modest for the average individual, and a 99.5% chance that it returns net monetary benefits that are greater than zero. Our findings are in line with previous reports from the literature. A Dutch study by Bijen et al17 also reported higher costs for TLH offset by a shorter hospital stay. Within the 3-month follow-up period, the QoL outcomes were similar between the two treatments. Further analysis of trial data found TLH cost-effective for patients >70 years of age, but not for very obese patients with body mass index > 35.18 In another clinical trial of hysterectomy for benign diagnoses, Garry et al19 not only reported higher complication rates for LH but also confirmed a shorter hospital stay and faster postoperative recovery compared to TAH. Sculpher et al20 found higher costs of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared to abdominal hysterectomy (£186) with similar QALYs resulting in incremental costs of £26 571 for each QALY gained. There was only a 56% probability that laparoscopic hysterectomy is cost-effective. It should be noted that health outcomes were not measured before or immediately after the procedure, but merely 6 weeks later which may underestimate true health benefits and hence understate the overall cost-effectiveness. The differences in hospital length of stay between the treatments were also small in this trial. A large difference of 3.55 days found in our data (table 1) was the main driver of cost savings.

Studies from the USA,21 Australia,22 France23 and the UK24 found costs of TAH and TLH to be similar or not significantly different and consistently reported a significantly shorter hospital stay for TLH. A recent cost comparison of different treatment approaches for endometrial cancer found TLH to be the least expensive alternative with costs ranging from US$6581–US$10 128 compared to US$7009–US$12 847 for TAH, depending on the range of costs included in the analysis.25 In contrast, a study by Lumsden et al26 with randomised Scottish patients reported higher overall costs for LH due to higher operation costs which were not compensated by the decreased length of stay or similar QoL outcomes. They concluded that LH is unlikely to be cost-effective in the National Health Services (NHS) context. Similarly, a large cross-sectional analysis by Campbell et al27 associated TLH with higher hospital costs. This was confirmed by Lenihan et al,28 but they also noted decreased indirect costs to employers due to a faster recovery and fewer hours at work lost.

Although cost estimates may vary due to different patient populations, perspectives, surgical and measurement techniques, the majority of recently published literature favours TLH over TAH economically.29 We believe that our findings derived from the large multicentre LACE trial represent an accurate estimate of outcomes. The use of TLH is recommended although decisions on the technique employed should be based on individual patient circumstances, including age and comorbidities. Future studies could look at long-term effects from a societal perspective. The data from Walker et al12 were used to show mortality risks for the two competing treatments. The reasons for this are their data were complete for a 5-year period and were audited with all follow-up-consistent and survival status obtained for each patient at the time of database lock, this is not the case for the LACE mortality outcomes; their publication has be reviewed by referees, statistical methods have been independently agreed upon and as such the survival curves for both groups reflect the scientific design for a non-inferiority equivalence design, this is yet to be achieved for the LACE trial.

Our data show that TLH is a safe and cost-effective treatment approach for early endometrial cancer and is likely to improve patients’ health outcomes whilst saving healthcare resources. The main drivers of the cost savings are reduced length of stay and reduced complications. Data from LACE11 however show complications were 14.3% for TAH and 8.2% in TLH, operating time was lower (132 vs 107 min) and length of stay in hospital was reduced from 5 to 2 days. Another recent study from the USA7 showed TLH had fewer moderate to severe postoperative adverse events (14% vs 21%), similar rates of intraoperative complications, but the length of hospital say was reduced by 2 days. To date, hysterectomy remains the most common major gynaecological surgical procedure, but the uptake of TLH amongst gynaecological surgeons has been slow. Further research might examine how a minimally invasive surgical approach can be established in real, day-to-day clinical practice to the benefit of women and their communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) for sharing their data on a 5-year mortality risk for laparotomy and laparoscopy patients. We thank all the women and all surgeons who participated in the LACE trial. We thank the LACE trial safety committee members Alex Crandon, Neville Hacker, Paul Vasey, and Alison Hadley and Peta Forder for providing trial methods expertise. We are grateful to all patients whose participation made this study possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: NG, MJ, KM, VG and AO all conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. NG and KM were responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. MJ, VG and AO provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by NG and KM and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. AO was responsible for the acquisition of the data and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The LACE trial was funded by Cancer Council Queensland, Cancer Council New South Wales, Cancer Council Victoria, Cancer Council Western Australia; NHMRC project grant 456110; Cancer Australia project grant 631523; the Women and Infants Research Foundation, Western Australia; Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Foundation; Wesley Research Institute; Gallipoli Research Foundation; Gynetech; TYCO Healthcare, Australia; Johnson and Johnson Medical, Australia; Hunter New England Centre for Gynaecological Cancer; Genesis Oncology Trust; and Smart Health Research Grant/QLD Health. MJ is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Award 1045247. The investigators also acknowledge the support of the Australian Gynaecological Endoscopy Society (AGES) to specifically conduct the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This is a modeling study, using existing data only.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide. Lyon, France: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]. ed. I.A.f.R.o. Cancer, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:10–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AIHW, Cancer in Australia Cancer series number 28. Canberra: AIHW, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacker NF. Uterine cancer. In: Berek JS, eds. Practical gynecologic oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000: 341–87 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrow CP, Curtin JP. Synopsis of gynecologic oncology. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janda M, Gebski V, Brand A, et al. Quality of life after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer (LACE): a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:772–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker JL. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 5331–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornblith AB. Quality of life of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing laparoscopic international federation of gynecology and obstetrics staging compared with laparotomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5337–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mourits MJ, Bijen CB, Arts HJ, et al. Safety of laparoscopy versus laparotomy in early-stage endometrial cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:763–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janda M, Gebski V, Forder P, et al. Total laparoscopic versus open surgery for stage 1 endometrial cancer: the LACE randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2006;27:353–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obermair A, Janda M, Baker J, et al. Improved surgical safety after laparoscopic compared to open surgery for apparent early stage endometrial cancer: results from a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1147–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:695–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Australian Government—Department of Health and Ageing Medicare Benefits Schedule Book, edn Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Australian Hospital Statistics 2005–06. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiroiwa T, Sung YK, Fukuda T, et al. International survey on willingness-to-pay (WTP) for one additional QALY gained: what is the threshold of cost effectiveness? Health Econ 2010;19:422–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briggs A, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bijen CB, Vermeulen KM, Mourits MJ, et al. Cost effectiveness of laparoscopy versus laparotomy in early stage endometrial cancer: a randomised trial. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121:76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bijen CB, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy is preferred over laparotomy in early endometrial cancer patients, however not cost effective in the very obese. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2158–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garry R, Fountain J, Brown J, et al. EVALUATE hysterectomy trial: a multicentre randomised trial comparing abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic methods of hysterectomy. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:1–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sculpher M, Manca A, Abbott J, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with standard hysterectomy: results from a randomised trial. BMJ 2004;328:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelmonem A, Wilson H, Pasic R. Observational comparison of abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy as performed at a university teaching hospital. J Reprod Med 2006;51:945–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsaltas J, Magnus A, Mamers PM, et al. Laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy: a cost comparison. Med J Aust 1997;166:205–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapron C, Fernandez B, Dubuisson JB. Total hysterectomy for benign pathologies: direct costs comparison between laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000;89:141–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon NV, Laveran RL, Cavanaugh S, et al. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy vs. abdominal hysterectomy in a community hospital. A cost comparison. J Reprod Med 1999;44:339–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett JC, Judd JP, Wu JM, et al. Cost comparison among robotic, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:685–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lumsden MA, Twaddle S, Hawthorn R, et al. A randomised comparison and economic evaluation of laparoscopic-assisted hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy. BJOG 2000;107:1386–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell ES, Xiao H, Smith MK. Types of hysterectomy. Comparison of characteristics, hospital costs, utilization and outcomes. J Reprod Med 2003;48:943–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenihan JP, Jr, Kovanda C, Cammarano C. Comparison of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with traditional hysterectomy for cost-effectiveness to employers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1714–20; discussion 1720–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hauspy J, Jiménez W, Rosen B, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometrial cancer: a review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:570–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.