Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to assess the perceived needs of medicines information and information sources for pregnant women in various countries.

Design

Cross-sectional internet-based study.

Setting

Multinational.

Participants

Pregnant women and women with children less than 25 weeks.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The need for information about medicines was assessed by a question: ‘Did you need information about medicines during the course of your pregnancy?’ A list of commonly used sources of information was given to explore those that are used.

Results

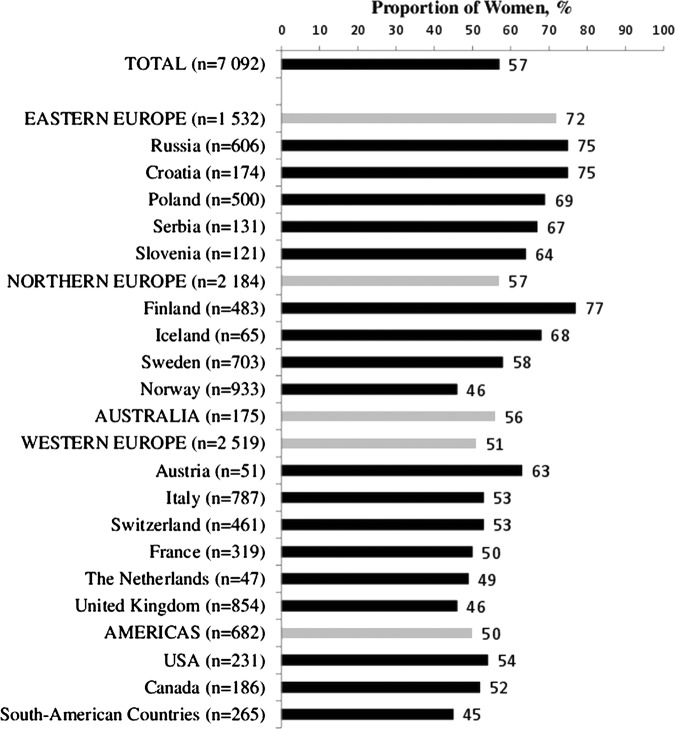

Altogether, 7092 eligible women responded to the survey (5090 pregnant women and 2002 women with a child less than 25 weeks). Of the respondents, 57% (n=4054, range between different countries 46–77%) indicated a need for information about medicines during their pregnancy. On average, respondents used three different information sources. The most commonly used information sources were healthcare professionals—physicians (73%), pharmacy personnel (46%) and midwifes or nurses (33%)—and the internet (60%). There were distinct differences in the information needs and information sources used in different countries.

Conclusions

A large proportion of pregnant women have perceived information needs about medicines during pregnancy, and they rely on healthcare professionals. The internet is also a widely used information source. Further studies are needed to evaluate the use of the internet as a medicines information source by pregnant women.

Article summary.

Article focus

Medicine use during pregnancy is common, and pregnant women often have questions related to medicine use.

Little is known about pregnant women's information needs and sources about medicines.

This study is the first to investigate pregnant women's information needs and sources on a multinational level.

Key messages

Over half of the pregnant women who responded to the internet survey in different countries indicated needing information related to medicine use during pregnancy.

Pregnant women use multiple information sources, however, with healthcare professionals, especially physicians, being the most common.

The internet is a widely used information source for pregnant women.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study adds a multinational perspective with a large number of respondents to the limited number of studies about pregnant women's information needs and sources.

An internet survey as a study method may cause selection bias of the target population.

Introduction

Medicine use during pregnancy is common.1 2 Most pregnant women use at least one medication during pregnancy.3 4 There is also evidence of an increase in the use of medicines during pregnancy, from an average number of 2.5 in 1976–1978 to 4.2 in 2006–2008 in the USA.4 Pregnant women's beliefs and risk perceptions influence their decisions on whether or not to use a medication during pregnancy.5 The availability and use of reliable information sources are therefore important to ensure safe and rational use of medicines during pregnancy. The increasing use of the internet and social media as a source of information and social support is challenging for the healthcare sector in trying to maximise its benefits and minimise its risks.

Health information needs and internet use of pregnant women have been studied more widely6–9 than the information needs concerning medicines in specific. Questions related to medicine use are among the four most important questions pregnant women have.10 Earlier studies have shown that some 40–80% of pregnant women have perceived information needs about medicine use during their pregnancy.2 11 12 The most commonly used source of information has been physicians/prenatal care providers,2 11–13 followed by pharmacists and family members.2 12 The use of books and magazines has also been reported.12 13 However, with growing access to the internet and social media, the role of healthcare personnel is bound to change from the keeper of information to the provider of coaching and assessing information including second opinions. It is also expected that women will use several different sources to compare the information content.

This study was the first to compare pregnant women's needs for information and sources about medicines in different countries. We hypothesise that the overall need for information about medications during pregnancy is widespread across different countries. Thus, our aim was to assess the perceived need for medicines information during pregnancy and which information sources are used in different regions of the world.

Material and methods

Study design and population

This study is part of a multinational collaborative study about Medication Use in Pregnancy. Member countries of Teratology Information Service network, that is, ENTIS in Europe, OTIS in North and South America and Mothersafe in Australia, were invited to take part in the project. Of these, the following countries/regions agreed to take part in the project and conduct the study: Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, Italy, France, the UK, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Russia, the USA, Canada, Australia and South America (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (n=7092), and comparative national population data (see online supplementary file 1)

| Age of mother | National data on age | Mother primiparous | National data on primiparity | Education, university/college | National data on education | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (IPR*) | Mean age | Per cent | Per cent | Per cent | Per cent | |

| Total | 7092 | 29 (23 to 36)† | 53 | 55 | |||

| Eastern Europe | 1532 | 28 (22 to 34) | 55 | 67 | |||

| Russia | 606 | 27 (21 to 34) | 27 | 56 | NA | 72 | NA |

| Croatia | 174 | 30 (24 to 36) | 28 | 59 | 47 | 62 | 44 |

| Poland | 500 | 27 (21 to 32) | 29 | 55 | 50 | 63 | 42 |

| Serbia | 131 | 29 (25 to 34) | 29 | 53 | 51 | 59 | 29 |

| Slovenia | 121 | 32 (26 to 37) | 30 | 50 | 49 | 71 | 43 |

| Northern Europe | 2184 | 29 (23 to 35)‡ | 52 | 54 | |||

| Finland | 483 | 29 (22 to 35) | 30 | 42 | 42 | 54 | 48 |

| Iceland | 65 | § | NA | 51 | 38 | 45 | 48 |

| Sweden | 703 | 30 (23 to 36) | 30 | 64 | 45 | 62 | 51 |

| Norway | 933 | 29 (23 to 35) | 30 | 49 | 42 | 48 | 55 |

| Australia | 175 | 31 (24 to 38) | 31 | 49 | 44 | 62 | 56 |

| Western Europe | 2519 | 31 (25 to 37) | 55 | 49 | |||

| Austria | 51 | 30 (23 to 36) | 30 | 57 | 48 | 45 | 23 |

| Italy | 787 | 32 (26 to 38) | 31 | 62 | 49 | 45 | 26 |

| Switzerland | 461 | 31 (26 to 37) | 31 | 49 | NA | 45 | 39 |

| France | 319 | 30 (24 to 37) | 30 | 54 | 44 | 58 | 47 |

| The Netherlands | 47 | 30 (23 to 36) | 31 | 40 | 46 | 23 | 44 |

| UK | 854 | 30 (23 to 37) | 30 | 54 | 42 | 53 | 46 |

| Americas | 682 | 28 (21 to 36) | 46 | 52 | |||

| The USA | 231 | 29 (21 to 37) | NA | 46 | 40 | 65 | 58 |

| Canada | 186 | 28 (21 to 34) | 30 | 52 | 43 | 68 | 70 |

| South-American Countries | 265 | 27 (20 to 34) | NA | 42 | NA | 30 | NA |

*Interpercentile range (IPR) calculated 10th to 90th percentile.

†Calculated based on 7028 values, because 64 values from Iceland were not available.

‡Calculated based on 2120 values, because 64 values from Iceland were not available.

§Not shown because 64 values were not available.

An anonymous self-completed internet-based questionnaire administered by the Questback programme (http://www.questback.com/) was used. Invitations to the study were posted on 1–4 internet websites used by pregnant women in regions around the world. Before being given access to the online questionnaire, each study participant had to read the study description in which the study objectives, participants’ right to withdraw from the study at any time and contact persons in the applicable country were presented. Each participant was then asked whether she was willing to participate in the study and fill out the online questionnaire. Only after clicking ‘yes’ was the participant redirected to the webpage on which the full online questionnaire could be filled in. Reading the study description and completing the questionnaire were considered to be giving informed consent.

The questionnaire was accessible during a period of 2 months in each country. All the data were collected during the period of 1 October 2011 to 29 February 2012. Pregnant women and breastfeeding women with a child less than 1-year old were eligible to participate in the study; however, in this substudy, only pregnant women and breastfeeding women with a child less than 6 months (less than 25 weeks) were eligible. The women were advised to answer the questions related to their current or latest pregnancy.

The number of women who accessed the on-line questionnaire in the various countries was 9615. Of these women, 9483 (98.6%) accepted the participation in the study and filled in the questionnaire. Of these responses, 5090 were from pregnant women and 2002 from women with a child less than 25 weeks old. Thus, the final study population was 7092 (figure 1). The study population in each country was compared with the birthing population using national or population-based statistics (see online supplementary file 1).

Figure 1.

Formation of final study population.

The ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Norwegian Regional Ethics Committee. All data were handled and stored anonymously.

Questionnaire

The internet questionnaire, originally developed by researchers at the University of Oslo (AL and HN), was first translated into English and then into the respective languages of the participating countries. The study questions largely followed the ones used in the study by Nordeng et al.2 5 The questionnaire was piloted in four countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland and Italy) and only minor changes were made. The pilot responses were not included in the study dataset.

The questionnaire included the following sections: background information about the pregnant woman and her pregnancy; health disorders and use of medicines during pregnancy; needs for information; medicines for chronic diseases during pregnancy; attitudes towards using medicines in general and during the pregnancy; and perceptions of risks during pregnancy. Standardised questions about maternal factors were posed to the subjects, with emphasis on the presence of acute and long-term illnesses during pregnancy. In affirmative case, women were questioned about the use of medicines for each individual illness as free-text entry. This study analyses and reports on the data about the information needs.

Main outcome measures

Women were asked about their needs for information regarding the use of medicines during pregnancy and the sources of information they had used. The need for information was assessed by a question: ‘Did you need information about medicines during the course of your pregnancy?’ A list of commonly used sources of information was also given to explore the information sources used, and the respondent had a chance to mention other sources used (table 2).

Table 2.

Medicines information sources used by pregnant women (n=4054)

| Physician, gynaecologist, specialist (%) | Internet (%) | Pharmacy personnel (%) | Drug handbook, Information leaflet (%) | Midwife, nurse (%) | Family, friends (%) | Drug information centre (%)* | Other (%)† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=4054) | 73 | 60 | 46 | 35 | 33 | 24 | 7 | 7 |

| Eastern Europe (n=1095) | 77 | 75 | 46 | 32 | 14 | 29 | 1 | 10 |

| Russia (n=456) | 70 | 90 | 35 | 26 | 12 | 33 | 0 | 13 |

| Croatia (n=130) | 71 | 78 | 54 | 38 | 3 | 26 | 0 | 17 |

| Poland (n=344) | 89 | 54 | 52 | 34 | 23 | 30 | 3 | 6 |

| Serbia (n=88) | 88 | 81 | 63 | 38 | 5 | 24 | 0 | 6 |

| Slovenia (n=77) | 68 | 64 | 55 | 47 | 12 | 12 | 1 | 5 |

| Northern Europe (n=1250) | 66 | 54 | 47 | 49 | 50 | 23 | 6 | 3 |

| Finland (n=372) | 67 | 59 | 57 | 50 | 54 | 20 | 19 | 2 |

| Iceland (n=44) | 64 | 46 | 46 | 41 | 59 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweden (n=408) | 57 | 56 | 49 | 61 | 65 | 23 | 1 | 3 |

| Norway (n=426) | 74 | 49 | 37 | 37 | 32 | 25 | 1 | 5 |

| Australia (n=98) | 74 | 54 | 54 | 28 | 49 | 21 | 24 | 5 |

| Western Europe (n=1273) | 75 | 52 | 47 | 28 | 33 | 21 | 9 | 7 |

| Austria (n=32) | 88 | 72 | 75 | 63 | 16 | 16 | 3 | 9 |

| Italy (n=419) | 89 | 52 | 42 | 33 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 7 |

| Switzerland (n=245) | 84 | 53 | 54 | 38 | 13 | 15 | 5 | 7 |

| France (n=159) | 77 | 45 | 63 | 11 | 29 | 23 | 5 | 6 |

| The Netherlands (n=23) | 83 | 70 | 35 | 61 | 39 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| The UK (n=395) | 52 | 51 | 42 | 18 | 68 | 31 | 13 | 7 |

| Americas (n=338) | 80 | 62 | 37 | 21 | 21 | 31 | 16 | 8 |

| The USA (n=124) | 81 | 74 | 35 | 29 | 27 | 30 | 24 | 7 |

| Canada (n=96) | 77 | 44 | 58 | 16 | 27 | 33 | 22 | 7 |

| South-American Countries (n=118) | 82 | 63 | 23 | 16 | 9 | 31 | 3 | 9 |

*Poison information centres, teratology information services and national centres of information on medicines.

†Herbal shop personnel, complementary medicine personnel, magazines, media and books.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences, V.20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used to analyse the data. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the results, that is, frequencies, percentages and cross-tabulation.

Results

Study population

The average age of the respondents was 29 years (interpercentile range 23–36; table 1). Of the respondents, 53% were primiparous, and 55% had a university or college degree. Overall, the mean age of our study populations is quite close to that of the target populations in each participating country (table 1). The percentage of primiparity was somewhat higher among our study participants than among most national populations. Likewise, our participants had a somewhat higher education when measured by the percentage of university or college graduates.

Information needs

Of the respondents, 57% (n=4054) stated having needed information about medicines during their pregnancy (figure 2). Respondents from Eastern Europe needed information the most (72%). The respondents in other regions of the world needed it less: Northern Europe 57%, Australia 56%, Western Europe 51% and North and South America 50%. The need for information varied between countries from 46% (the UK and Norway) to 77% (Finland).

Figure 2.

Women's perceived need for information about medicines during pregnancy.

Information sources

The most commonly used information sources were healthcare professionals, especially physicians (73%), pharmacy personnel (46%), midwifes or nurses (33%) and the internet (60%; table 2). On average, the respondents used three different information sources.

There were differences in the information sources used in different countries. Midwives and nurses were often asked for information in Northern Europe (50%), but they were rarely contacted in Eastern Europe (14%). On the other hand, the internet was most commonly used in Eastern Europe (75%). Pregnant women in Northern Europe (49%) used drug handbooks and information leaflets more often than women in other parts of the world. Drug information centres were commonly used in Australia (24%) and the USA (24%), but they were very rarely used in Eastern Europe (1%). Pregnant women in Eastern Europe (10%), especially in Croatia (17%) and Russia (13%), reported using other sources of information such as magazines, media, books and complementary medicine personnel. On average, one-fourth of the respondents discussed medicine use with their family and friends.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess women's needs for medicine information during pregnancy on a multinational level. Over half of the pregnant women who responded to the internet survey in different countries indicated a need for information related to medicine use during pregnancy. Pregnant women used multiple information sources, however, healthcare professionals, especially physicians, being the most common. The internet was also a widely used information source for pregnant women. There were distinct differences in the perceived needs for information and sources of information used in different countries.

The fact that most of the pregnant women in this as well as previous studies report using healthcare professionals as a source is reassuring.2 11 12 Physicians are the key persons when counselling pregnant women on medicine use. However, our results show that the internet is also commonly used today in different regions of the world (ranging from 45% to 90%) by pregnant women. This is consistent with some previous studies.2 7 9 12 The differences in information sources used between different countries most probably reflect different situations in terms of antenatal care as well as available information sources in the countries. For example, in Eastern Europe, where women did not often use midwives or nurses as information sources, the use of the internet was most common. On the other hand, in Australia the use of drug information centres was high, most probably because of the availability of such centres. The prevalent use of the internet is challenging for healthcare professionals. Increased awareness and readiness to accept this is necessary to ensure a rational approach towards the use of the internet in health contexts.

Our findings may reflect that pregnancy is a special time when the need for information is great, but the findings could also be a more general cohort effect reflecting the generations of young women today. The societal change in the information society is concretised by Palfrey and Gasser's14 definitions of ‘Digital Natives’ as those generations born after 1980 and ‘Digital Immigrants’ as those born before 1980. Thus, the new generations internalise new forms of information and communications technologies from childhood in a way that has not happened before. Information about medicines is readily available for everyone and Digital Natives find it and use it particularly easily. In this study, the average age of the respondents was 29 years, indicating that most of them were Digital Natives, and thus natural internet users.

The development of the information society and eHealth initiatives is aimed at empowering the consumer and client. This is also in line with current trends in healthcare from paternalism towards concordance.15 16 At the same time, the role of healthcare professionals should expand from a mere information provider to a supporter of care of an empowered patient. Healthcare professionals need to be ready to discuss any topics raised on health and medicines information although there are some reports indicating that pregnant women are not very prone to discuss information retrieved from internet with their midwife.7 9 Healthcare professionals need to discuss with their clients about what information sources they use, interpret health information and tailor it to specific needs. Moreover, there is also a growing need to assess the quality of information with clients. It is important to promote the use of tools such as the DARTS checklist17 for the assessment of the quality of online medicines information.

eHealth functions are much broader than just medicines information, as they include functions such as health information networks, electronic health records, health portals and all kinds of tools to assist prevention, diagnosis, treatment, health monitoring and lifestyle management. As such, this major change in the healthcare sector also changes the way the medicines information is delivered to medicine users. In fact, there is a need for being prepared to increase visibility and participation of healthcare professionals on the internet and social media to balance lay views on issues related to health and medicines. In the European Union, an eHealth action plan was adopted in 200418 aimed at facilitating a more harmonious and complementary European approach to eHealth. The action plan is currently being revised.19

One limitation of our study is the fact that the questionnaire was only available through internet websites used by pregnant women. Using this kind of approach, a conventional response rate cannot be calculated. However, epidemiological studies using web-based recruitment methods have shown reasonable validity.20–22 Internet use is relatively high among individuals aged 25–34 years in Europe, ranging from 48% in Russia to 100% in Iceland.23 The internet penetration rates in other parts of the world vary, being highest in the USA, Australia, and Canada (80–94%) and lowest in South America (48%).24–27 Thus, the degree to which our findings can be extrapolated to the target population is based on the representativeness of the respondents to the general birthing populations in each country. Overall, the age structure of our study population match quite well with the target population in each participating country. However, as in most questionnaire-based studies, the participating women had somewhat higher educational level than the general birthing populations in each country. It is commonly known that more resourceful individuals tend to be more favourable to participate in questionnaire-based studies.28 29 This is likely the case for this study as well since the study population is better educated than the general birthing population. As women with higher education tend to seek information and to a larger degree use several sources,28 30 we might have overestimated the need for information about medicines during pregnancy. Among our study population, we had also somewhat more primiparous women indicating a higher need for medicines information in this subgroup. Finally, we do not know which internet websites the respondents have used. Some of the information used may be highly reliable and relevant, while others may be unreliable or biased.

In conclusion, a large proportion of pregnant women report the need for information about medicines during pregnancy, and they rely on healthcare professionals. The internet is also a widely used information source across the countries in this study. Further studies are needed in order to evaluate internet use as a medicines information source by pregnant women.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HN and AL conceived and collected data for the main study ‘Medication Use in Pregnancy—an International study’. KH-A, JJ, HE, HN and AL conceived this substudy. EK performed the statistical analysis and KH-A wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the final manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study has received support by the Norwegian Research Council (grant no. 216771/F11).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Norwegian Regional Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available. Researchers can apply for data access for subprojects within the overall aims of the main study ‘Medication Use in Pregnancy—an International Study’.

References

- 1.Daw JR, Hanley GE, Greyson DL, et al. Prescription drug use during pregnancy in developed countries: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:895–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordeng H, Ystrøm E, Einarson A. Perception of risk regarding the use of medications and other exposures during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olesen C, Søndergaard C, Thrane N, et al. Do pregnant women report use of dispensed medications? Epidemiology 2001;12:497–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstetr 2011;205:51:e1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordeng H, Koren G, Einarson A. Pregnant women's belief about medications—a study among 866 Norwegian women. Ann of Pharmacother 2010;44:1478–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhillon AS, Albersheim SG, Alsaad S, et al. Internet use and perceptions of information reliability by parents in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 2003;23:420–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsson M. A descriptive study of the use of internet by women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery 2009;25:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. Internet use in pregnancy informs women's decision making: a web-based survey. Birth. 2010;37:106–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao LL, Larsson M, Luo SY. Internet use by Chinese women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery 2012. Epub ahead of print: doi:10.1016/j.midw.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shieh C, McDaniel A, Ke I. Information-seeking and its predictors in low-income pregnant women. J Midwifery Women's Health 2009;54:364–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Trigt AM, Waardenburg CM, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, et al. Questions about drugs: how do pregnant women solve them? Pharm World Sci 1994;16:254–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakhireva LN, Young BN, Dalen J, et al. Patient utilization of information sources about safety of medications during pregnancy. J Reprod Med 2011;56:339–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry A, Crowther C. Sources of advice on medication use in pregnancy and reasons for medication uptake and cessation during pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;40:173–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palfrey J, Gasser U. Born digital: understanding the first generation of digital natives. New York: Basic Books, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain From compliance to concordance: achieving shared goals in medicine taking. London: Merck, Sharp and Dohme, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Medicines adherence. Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11766/42891/42891.PDF (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 17.Närhi U, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä M, Karjalainen A, et al. The DARTS tool for assessing online medicines information. Pharm World Sci 2008;30:898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Commission Europe's Information Society—Thematic Portal. The right prescription for Europe's eHealth. http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/health/policy/index_en.htm (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 19.Commission of the European Communities eHealth—making healthcare better for European citizens: An action plan for a European eHealth Area. Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels: COM(2004)356 final. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2004:0356:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 20.Ekman A, Dickman PW, Klint Å, et al. Feasibility of using web-based questionnaires in large population-based epidemiological studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2006;21:103–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huybrechts KF, Mikkelsen EM, Christensen T, et al. A successful implementation of e-epidemiology: the Danish pregnancy planning study ‘Snart-Gravid’. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Gelder MMHJ, Bretveld RW, Roeleveld N. Web-based questionnaires: the future in epidemiology? Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:1292–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seybert H. Internet use in households and by individuals in 2012. Statistics in focus 50/2012. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-12-050/EN/KS-SF-12-050-EN.PDF (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 24.Internet World Stats Usage and Population Statistics. http://www.internetworldstats.com/ (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 25.Australian Bureau of Statistics Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2010–11. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/8146.0 (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 26.Statistics Canada Individual Internet use and E-commerce 2010. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/111012/dq111012a-eng.htm (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 27.United States Census Bureau The 2012 Statistical Abstract. The National Data Book. Information & Communications: Internet Publishing and Broadcasting and Internet Usage. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/information_communications/internet_publishing_and_broadcasting_and_internet_usage.html (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 28.Plantin L, Daneback K. Parenthood, information and support on the internet. A literature review of research on parents and professionals online. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorence D, Park H. Study of education disparities and health information seeking behaviour. Cyberpsychol Behav 2007;10:149–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khoo K, Bolt P, Babl FE, et al. Health information seeking by parents in the Internet age. J Paediatr Child Health 2008;44: 419–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.