Abstract

Background

Transitions of care between providers are vulnerable periods in healthcare delivery that expose patients to preventable errors and adverse events. Patient discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU) to a medical or surgical hospital ward is one of the most challenging and high risk transitions of care. Approximately 1 in 12 patients discharged will be readmitted to ICU or die before leaving the hospital. Many more patients are exposed to unnecessary healthcare, adverse events and/or are disappointed with the quality of their care. Our objective is to conduct a scoping review by systematically searching the literature to identify ICU discharge planning tools and their supporting evidence-base including barriers and facilitators to their use.

Methods and analysis

Systematic searching of the published health literature will be conducted to identify the existing ICU discharge planning tools and supporting evidence. Literature (research and non-research) reporting on the tools used to facilitate decision making and/or communication at ICU discharge with patients of any age will be included. Outcomes will include adverse events and provider and patient/family-reported outcomes. Two investigators will independently review the abstracts (screen 1) to identify those meeting the inclusion criteria and then independently assess the full text articles (screen 2) to determine if they meet the inclusion criteria. Data collection will include information on citations and identified tools. A quality assessment will be performed on original research studies. A descriptive summary will be developed for each tool.

Ethics and dissemination

Our scoping review will synthesise the literature for ICU discharge planning tools and identify the opportunities for knowledge to action and gaps in evidence where primary evidence is necessary. This will serve as the foundational element in a multistep research programme to standardise and improve the quality of care provided to patients during ICU discharge. Ethics approval is not required for this study.

Keywords: Intensive & Critical Care

Background

The transfer of responsibility for patient care (synonyms include transition of care, handoff, sign over, etc) is a common practice in acute care hospitals.1 During transfers of patient care, crucial information on patient conditions, tests undertaken and treatments received is transferred between providers, so that care plans can be effectively continued by receiving providers. A handoff between healthcare providers is not only a process to provide accurate and vital information regarding patients’ care, but also a transfer of accountability and responsibility for patient care.2–7 Healthcare organisations recognise the importance of transitions of care and have proposed organisational practices to improve the effectiveness and coordination of communication among providers and recipients of care across the care continuum.3 8 9

Unfortunately, the practice of provider handoff is often suboptimal because of communication barriers6 10–12 and is a major contributor to medical errors and adverse events.2 7 13–19 The Harvard Medical Practice Study20 found that adverse events occur in approximately 4% of patients discharged from hospital, with three quarters of these adverse events resulting in patient disability (ranging from less than 1 month duration to permanent). A similar Australian study reported adverse events resulting in disability or increased length of stay for 17% of patients admitted to hospital.21 In 2006, the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Health Care Organization (JCAHO) reported that 63% of deaths related to medical error in its sentinel events database involved a breakdown in communication.22 Most research on handoffs for in-hospital patient transfers has focused on patient transfers from the perspective of a single discipline, such as physician end-of-shift1 6 11 18 23 or end-of-service2 16 17 24 handoffs. In contrast, relatively little is known about the handoffs between non-physician providers.10 25 Multidisciplinary handoffs though are required to optimally transition care and likely face relatively greater communication hurdles owing to cultural differences, work load challenges and differences in clinical focus between specialties and disciplines, and thus may lead to greater potential for medical errors and adverse events.10 12 25

Numerous types of patient transfers and provider handoffs occur every day.4 6 A transition of care occurs each time a patient is referred to a specialist by their family doctor, assigned a new nurse during hospital shift change or discharged from hospital. Among these, patient transfers from the intensive care unit (ICU) to a medical or surgical hospital ward are likely of particularly high risk owing to the number, complexity and acuity of the medical conditions that characterise this patient group26–29; the large ‘voltage’ drop in available resources when patients move from the ICU, where medical care is intensive and resources are rich, to ward environments, where patients typically receive much less intensive monitoring and patient care26; the multitude of communication barriers that providers often face during interspecialty and multidisciplinary handoffs30; the lack of standardisation in patient transfer processes overall; and, in particular, the lack of standardised written and/or electronic tools to facilitate an optimal transfer process.28

Patients admitted to the ICU are of the highest acuity requiring management with life support technologies and aggressive interventions to sustain life and progress towards a clinically stabilised condition.28 Approximately 1 in 10 patients admitted to an acute care facility is admitted to an ICU.31 Transition of care is extremely common with 90% of ICU patients being eventually discharged to medical or surgical hospital wards.32 With millions of hospitalisations in acute care facilities in most countries each year,31 hundreds of thousands of patients will be admitted to ICU and experience challenging and high risk transfers to hospital wards.

ICU discharge represents a large drop in the intensity of care with patients transitioning from a high acuity unit to a general care unit. ICUs are specially staffed, self-contained hospital units, dedicated to the management and continuous monitoring of patients with life-threatening illnesses.33 The medical support available to patients in the ICU includes multidisciplinary teams of healthcare providers (ie, physicians, nurses, pharmacists and therapists) that typically see each patient multiple times a day.34 35 In general, there is a nurse for every one or two patients and a physician for every 8 to 10 patients.36 37 In contrast, general medical and surgical care units have fewer resources with a nurse for every four to eight patients38 and physicians responsible for up to as many as 65 patients during regular working hours and 400 patients outside of regular working hours.39 Other healthcare providers are often less available.

When a patient is transferred from ICU to a general care unit, typically there is a complete transition in healthcare providers, most patients being assigned new teams of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, etc. However, communication between providers discharging patients from the ICU and providers admitting these patients to general care units has been documented to be infrequent, incomplete and of poor quality.30 40 An observational study performed by our research team in preparation for this protocol found direct verbal communication between ICU-discharging physicians and ward-admitting physicians to occur in only 15–25% of the ICU discharges.30 Optimal transfers of care require effective communication between discharging and admitting physicians that include direct communication (in person or via telephone); concise, accurate, up-to-date discharge summaries; and physician notification at the time of transfer.3 30 However, communication during transfer is challenged by provider workloads, available resources and variations in clinical focus between specialties.10 12 25

Communication between physicians and patients/families at the time of ICU discharge is also frequently suboptimal with the same local observational study finding 68% of patient/families reporting a desire for increased opportunities to ask questions about the transfer.30 This lack of information about the ICU transfer process appears to be associated with patient and family anxiety.41–44Effective communication between providers and patients/families to provide early notification of an upcoming transfer,30 present information on current medical conditions and future plans prior to transfer would likely better manage expectations and reduce anxiety.

Standardising the process of patient discharge from ICU could improve the safety, quality and efficiency of care. Multiple interventions to improve ICU discharge have been developed (eg, transitional care units, ICU outreach, nursing liaison, etc),28 45–48 but there is no consensus on an ideal ICU discharge model to optimise the quality of patient care28 and few organisations have implemented standardised guidelines or procedures for transitions of care.46 49 Government agencies,50 specialty groups3 51 52 and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement53 have all advocated standardising ICU discharge structure and processes to improve continuity of care, patient safety, patient and provider satisfaction and resource use.47 54

The challenges of ICU discharge are well recognised.28 55 Very little is known about the quality of patient care during ICU discharge. A comprehensive review of ICU discharge planning tools has not been previously completed. The scope and magnitude of tools to facilitate patient discharge from ICU has not been previously defined. For tools already developed, it is unclear how effectively these have been implemented and how they may have affected patient clinical outcomes and/or patient and family satisfaction with care. In response to these challenges, we will conduct a scoping review to identify ICU discharge planning tools and the supporting evidence base for these tools including barriers and facilitators to their use.

Methods and analysis

Conceptual model

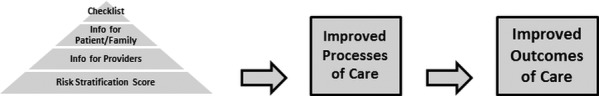

Our scoping review will adopt the model of system theory first introduced in 1966 by Avedis Donabedian.56 57 In Donabedian's framework, the three components of healthcare quality are structure, process and outcome. The structure is the environment in which healthcare is provided and includes material and health resources, operational factors and organisational characteristics of the healthcare facility. The process is the method by which healthcare is provided and includes the giving and receiving of care by the providers and healthcare system. The outcome is the consequence of healthcare and includes the health status of patients. We will examine structural devices (tools) used to facilitate ICU discharge and evaluate their association with processes and outcomes of care for patients discharged from ICU (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual evidence-based intensive care unit discharge planning tool.

In addition, we will incorporate the Institute of Medicine's (IOM's) six aims for the 21st Century Health Care System into our research. ICU discharge tools should foster safe, effective, efficient, timely, equitable and patient-centered discharge from ICU. We have developed a conceptual model for our scoping review that merges the Donabedian model and the IOM's six aims (table 1). We recognise that our conceptual model is a relatively basic and simple representation of ICU discharge, but no other simple validated framework exists and we have successfully used a variation of this model to develop quality indicators for injury care.58–61

Table 1.

Conceptual model of ICU discharge*

| IOM aims | Structure (discharge tool) | Process | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safe | Risk stratification | Patient to right ward | ↓ ICU readmission |

| Effective | Medication reconciliation | Right medications | ↓ Adverse event |

| Efficient | Information for providers | Providers informed | ↓ Duplication of tests |

| Timely | Risk stratification | Discharged when ready | ↓ Length of stay |

| Patient-centered | Information for patients | Patients engaged | ↑ Patient satisfaction |

| Equitable | Checklist | Equal access | ↓ Inequalities |

*Table populated with sample tool components and consequent processes and outcomes.

ICU, intensive care unit; IOM, Institute of Medicine.

Objectives

This is a protocol for a scoping review to identify ICU discharge planning tools and the supporting evidence base for these tools including barriers and facilitators to their use. Methods for inclusion and analysis of articles and reporting of their results will be performed as recommended by Arksey and O'Malley62 and refined by Levac et al.63

We define an ICU as a distinct hospital ward that is staffed by specialised healthcare professionals and where immediate and continuous life-sustaining treatment (eg, invasive monitoring, vasoactive medications and invasive mechanical ventilation) is administered to hospitalised patients suffering from life-threatening conditions (eg, severe respiratory failure).36 Patient's discharge from ICU is defined as the transfer of accountability and responsibility for patient care from the ICU to a hospital ward. Tools are defined as structural devices (eg, protocols, reminders, order sets, bundles, checklists, forms and decision aids) designed to aid healthcare providers or patients/families with decision making and/or communication.64

The specific objectives of the scoping review are

To complete a systematic search of the literature to identify existing ICU discharge planning tools and evaluate the evidence base in support of the tools (including impact on patient outcomes).

To map the ICU discharge planning tools and the supporting evidence to our conceptual framework to identify gaps in the evidence where primary evidence or systematic reviews are required.

To evaluate the tools according to their relevance to knowledge users (importance, feasibility, usability and scientific acceptability).

To describe barriers and facilitators to the implementation and utilisation of ICU discharge planning tools.

Eligibility criteria

Research studies (no methodological restrictions—case series, cohort, cross-sectional, non-randomised controlled, consensus method, case–control and randomised controlled) and non-research study designs (editorial, guideline, letter to the editor and narrative review) are eligible. We will include studies with all human patients discharged from any ICU regardless of subspecialty (eg, medical, neuroscience, etc). There is no restriction on age, as tools identified for neonatal and paediatric patients may provide relevant information for the discharge of adult patients (and vice versa).

Eligible studies must include an electronic or paper tool (including guidelines, protocols, questionnaires, checklist, etc) intended to facilitate discharge from ICU (regardless of discharge destination) either by providing decision support for healthcare providers and/or patients/families to determine readiness for discharge or aid in guiding the process of patient discharge. A comparison group is not required as we will be looking for studies that describe the development, implementation or evaluation of a tool. If evaluation studies are identified, details on the comparison group will be assessed including patients, type of ICU (eg, medical, neuroscience, etc) and discharge destination (eg, high dependency step down unit, hospital ward, etc). Outcome measures will include (1) any severe adverse events post-ICU discharge (eg, ICU readmission and hospital mortality), (2) any provider reported outcomes (eg, quality of communication and satisfaction) or (3) any patient/family reported outcomes (eg, quality of information, engagement and satisfaction).

Studies will be excluded if they include patient discharges predominantly from coronary care units, high dependency units and step-down units.

Search strategy

We will search the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (OVID interface, 1946 onwards), EMBASE (OVID interface, 1947 onwards), CINAHL (EBSCO interface, 1981 onwards) and the Cochrane Library (current issue). Bibliographies of the retrieved articles will be searched for additional relevant articles. We will also search conference proceedings from the past 5 years, including the Canadian Critical Care Conference, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Conference, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Conference, American Thoracic Society Conference, and International Symposium on Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Experts in the field, identified from the references of included studies will be contacted to determine whether they are aware of any additional studies.

An experienced information specialist (LP) will conduct the literature searches. It will be performed with no year or language restrictions and will use combinations and synonyms of the following search terms: intensive care, critical care, discharge plan, patient transfer and patient discharge. Appropriate wildcards will be used to account for plurals and variations in spelling. A draft literature search is available in online supplementary additional file 1.

Study selection process

Two investigators will independently review the retrieved abstracts (screen 1) to identify those that meet the inclusion criteria. The full text of those articles deemed relevant by either reviewer will be obtained. Two investigators will independently assess the full text articles (screen 2) to determine if they meet the inclusion criteria. Two investigators will discuss disagreements on inclusion and a third investigator will resolve disagreements if needed. Bibliographic details will be downloaded to EndNote.65 The study selection process will be pilot tested using 50 citations from the literature search. The inclusion and exclusion criteria will be serially clarified and reviewer training sequentially revised until reliable study selection can be demonstrated (estimated κ≥0.6).66

Data items and data collection process

The data collection instruments will include information on both citations and identified tools. We will document the type of citation (eg, original research), country, setting (eg, subspecialty of unit), study design, study population, recruitment and sampling, diagnostic criteria, reference standard, blinding, statistical methods and outcomes. For each tool, we will document the name, purpose (eg, patient evaluation for discharge, planning patient discharge, etc), components (single component vs multicomponent), how it is applied (eg, electronic) and the timing of activation (eg, discharge planning vs discharge execution). If available, we will record any measurement properties documented (sensitivity/specificity), reported impact on processes (eg, medication reconciliation) and outcomes (eg, patient readmission to ICU) of care for patients, families and providers and barriers and facilitators identified to use of the tool (eg, organisational culture). The data collection instrument and reviewer training will be sequentially revised until reliable data abstraction can be demonstrated (estimated κ≥0.8).66 Differences in coding between the two reviewers will be resolved by discussion and a third reviewer will be consulted if an agreement cannot be reached. Original research studies will have the quality of their methodology assessed using the framework of Caldwell et al67 for evaluating both quantitative and qualitative study designs. Three clinical decision-makers (DZ, PB and DJZ) will independently judge the relevance of each tool for decision-making according to four dimensions derived from the Strategic Framework Board in the USA68: (1) targets important improvements in the continuity of patient care, (2) feasible to implement, (3) easy to use and (4) strength of scientific evidence (using the GRADE criteria).69

Analysis

Quantitative and qualitative analyses will be performed. The articles and tools will be categorised according to their respective criteria. Agreement on data abstraction and article classification will be assessed with Cohen κ-reliability coefficients.66 A comprehensive list of tools will be developed and summarised using simple numerical counts. We will present the distribution of tools according to the cells of our conceptual model along with binomial 95% CIs as well as detailed tabulations by type of article (original research and non-research) and study design. We will examine the purpose and components of the tools from each study as well as the reported measurement properties (eg, sensitivity/specificity of risk stratification tools) and reported processes (eg, hospital length of stay) and outcomes (eg, readmission to ICU) of care. A descriptive summary of each tool's purpose, components, conceptual model classification, measurement properties and relevance to knowledge users will be developed.

Qualitative studies will be evaluated by identifying the key outcomes and themes presented by each study (eg, reported barriers and facilitators to discharge tool utilisation), preserving the meaning from their original source and tabulating them within the review. Translation of key concepts from all studies will be performed to identify novel concepts not explored by individual studies. Analysis will focus on identifying the overlap of key concepts between studies. Finally, the translated concepts will be synthesised and refined to identify core themes.70

Using the above categorisation scheme, we will be able to provide a scoping review of what research is available in the area of ICU discharge planning tools and the evidence base supporting available tools. From this, we will identify where there is a need for a systematic review of the literature (eg, there may be sufficient literature on validated risk stratification techniques) and where gaps in the literature exist and primary prospective studies are needed.

Ethics and dissemination

This scoping review is the first step in a major empiric work to measure and improve ICU discharge processes (focused on adult patients). It will identify the fundamental information needed to implement an ICU discharge planning tool. This review will identify existing tools to facilitate ICU discharge, the supporting evidence base as well as facilitators and barriers to implementation. All data will be obtained from publicly available materials, and therefore this study will not require ethics approval.

Our knowledge translation strategy will involve, among other approaches, a workshop to be held in conjunction with the annual January Canadian Critical Care Trials Group meeting that will bring together key target audiences across disciplines for our research. By engaging multidisciplinary stakeholders, we will enhance linkages necessary for dissemination of our results. We will engage stakeholders in a discussion of the results and develop and prioritise a research agenda for the implementation of a standardised ICU discharge planning tool. We will publish in health services research and discipline-based journals. In addition, we will encourage presentation of findings at health services research conferences at national and international meetings including the annual meetings of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, and International Symposium of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine among others.

Our scoping review results have the potential to influence the care of many patients. We will synthesise the literature for ICU discharge planning tools and identify the opportunities for knowledge to action and gaps in evidence where primary evidence is necessary. ICUs are specialised units that have been widely implemented around the world to care for the sickest patients in the healthcare system.55 Discharge from ICU is a high risk process because vulnerable patients move from a resource rich environment to a relatively resource poor environment using a process that is non-standardised, inefficient and characterised by poor communication and frequent adverse events.29 30 40 45 46 71 72 To improve patient care, we need evidence-based tools to standardise and improve the quality of care provided to patients during ICU discharge. Our results will help in implementing an evidence-based ICU discharge planning tool to ensure that discharge from the ICU is safe, effective, efficient, timely, equitable and patient-centered so that the right patient is discharged at the right time using a process that improves patient care and reduces the risk of adverse events and hospital mortality while facilitating patients’ care journeys.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephanie Todd and Jamie Boyd for their help in formatting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: HTS, LP, SES, WAG, DZ, PB, DJZ contributed to concept and design of the study, edited the protocol and obtained funding. HTS drafted the protocol. All authors read and approved the final protocol.

Funding: The project is supported by a Synthesis Grant (KRS124604) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Competing interests: HTS is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Population Health Investigator Award from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. SES is funded by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair. WAG is funded by a Senior Health Scholar Award from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. DZ is supported by a Clinical Investigator Award from Alberta Innovates. Funding sources had no role in the design of the protocol and we are unaware of any conflicts of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Horwitz LI, Krumholz HM, Green ML, et al. Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1173–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen LA, Brennan TA, O'Neil AC, et al. Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med 1994;121:866–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Council on Health Service Accreditation. CCHSA patient/client safety goals and required organizational goals: evaluation of implementation and evidence of compliance. Version of 2.1 for use with 2007 standard. http://www.accreditation.ca/uploadedFiles/CHAR-2012-en.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2012)

- 4.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:533–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson ES, Roth EM, Woods DD, et al. Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16:125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, et al. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med 2005;80:1094–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, et al. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:401–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Joint Commission of Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations National patient safety goals. http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx (accessed 28 Feb 2012)

- 9.Institute of Health Improvement IHI improvement map: patient transitions & handoffs. http://app.ihi.org/imap/tool/#Process=21e273fb-81fc-4dd2-b89b-883c10afc4bc (accessed 28 Feb 2012)

- 10.Apker J, Mallak LA, Gibson SC. Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician hospitalist handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:884–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shojania KG, Fletcher KE, Saint S. Graduate medical education and patient safety: a busy—and occasionally hazardous—intersection. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:592–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med 2009;84:1775–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews C, Millar S. Don't fumble the handoff. Inpatient providers, specialists, and the primary care physician: a medical care delivery system with benefits and complex risks. J Med Assoc Ga 2007;96:23–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gandhi TK. Fumbled handoffs: one dropped ball after another. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:352–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, et al. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1755–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, et al. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:248–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitch BT, Cooper JB, Zapol WM, et al. Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:563–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, et al. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2030–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med 2004;79:186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 1991;324:370–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, et al. The quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust 1995;163:458–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Using medication reconciliation to prevent errors. Sentinel Event Alert 2006;35:1–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher KE, Saint S, Mangrulkar RS. Balancing continuity of care with residents’ limited work hours: defining the implications. Acad Med 2005;80:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landucci D, Gipe BT. The art and science of the handoff: how hospitalists share data. Hospitalist 1999;3:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horwitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, et al. Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:701–10, e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cullen DJ, Sweitzer BJ, Bates DW, et al. Preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: a comparative study of intensive care and general care units. Crit Care Med 1997;25:1289–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voigt LP, Pastores SM, Raoof ND, et al. Review of a large clinical series: intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: outcomes, timing, and patterns. J Intensive Care Med 2009;24:108–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts R, Pierson J, Gardner H. Coordination of the discharge process planning in critical care. J Clin Nurs 2005;21:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg AL, Watts C. Patients readmitted to ICUs* : a systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. Chest 2000;118:492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li P, Stelfox HT, Ghali WA. A prospective observational study of physician handoff for intensive-care-unit-to-ward patient transfers. Am J Med 2011;124:860–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leeb K, Jokovic A, Sandhu M, et al. CIHI survey: intensive care in Canada. Healthc Q 2006;9:32–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell S. Reducing readmissions to the intensive care unit. Heart Lung 1999;28:365–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.College of Intensive Care Medicine Minimum standards for intensive care units. http://www.cicm.org.au/cmsfiles/IC-01%20Minimum%20Standards%20For%20Intensive%20Care%20Units%20-%20Current%20September%202011.pdf (accessed 28 Feb 2012).

- 34.Dutton RP, Cooper C, Jones A, et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma 2003;55:913–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vazirani S, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on communication and collaboration among physicians and nurses. Am J Crit Care 2005;14:71–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Society for Critical Care Medicine Practicing CCM. http://www.sccm.org/AboutSCCM/Public%20Relations/Media_Kit/Pages/Practicing_CCM.aspx (accessed 23 Mar 2012)

- 37.Ward NS, Read R, Afessa B, et al. Perceived effects of attending physician workload in academic medical intensive care units: a national survey of training program directors. Crit Care Med 2012;40:400–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002;288:1987–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goddard AF, Hodgson H, Newbery N. Impact of EWTD on patient:doctor ratios and working practices for junior doctors in England and Wales 2009. Clin Med 2010;10:330–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin F, Chaboyer W, Wallis M. A literature review of organizational, individual, and teamwork factors contributing to the ICU discharge process. Aust Crit Care 2009;22:29–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gustad LT, Chaboyer W, Wallis M. ICU patient's transfer anxiety: a prospective cohort study. Aust Crit Care 2008;21:181–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell ML, Courtney M. Reducing family members’ anxiety and uncertainty in illness around transfer from intensive care: an intervention study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2004;20:223–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forseberg A, Lindgren E, Engström Å. Being transferred from an intensive care unit to a ward: searching for the known in the unknown. Int J Nurs Pract 2011;17:110–16 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strahan EH, Brown RJ. A qualitative study of the experiences of patients following transfer from intensive care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2005;21:160–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, et al. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2007;2:314–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heidegger C, Treggiari M, Romand J, et al. A nationwide survey of intensive care discharge practice. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:1676–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips C, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA 2006;297:831–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watts R, Pierson J, Gardner H. How do critical care nurses define the discharge process. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2004;21:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levin P, Worner T, Sviri S, et al. Intensive care outflow limitation—frequency, etiology, and impact. J Crit Care 2003;18:206–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wachter RM. Making healthcare safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evidence Report No 43. Edited by Agency for Healthcare Quality Research, AHRQ publication 01-E058 edn Rockville, MD, USA, 2001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Joint Commission of Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Critical access hospital: 2012 National Patient Safety Goals. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/NPSG_Chapter_Jan2012_CAH.pdf (accessed 11 Mar 2012)

- 52.The National Quality Forum. Safe practices for better healthcare: a consensus report. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nqfpract.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2012)

- 53.Berwick DM, Calkins DR, McCannon CJ, et al. The 100,000 lives campaign: setting a goal and a deadline for improving health care quality. JAMA 2006;295:324–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boutilier S. Leaving critical care: facilitating a smooth transition. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2007;24:137–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, et al. Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2787-93e2781-2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donabedian A. The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q 2005;83:691–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stelfox HT, Bobranska-Artiuch B, Nathens A, et al. Quality indicators for evaluating trauma care: a scoping review. Arch Surg 2010;145:286–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stelfox HT, Bobranska-Artiuch B, Nathens A, et al. A systematic review of quality indicators for evaluating pediatric trauma care. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1187–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stelfox HT, Nathens AB, Straus SE, et al. Assessing care of patients with major traumatic injuries (Funding Reference #200803PH E-188220-PH M-CBBA-587 44). University of Calgary: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2008-10-01 to 2011-09-30.

- 61.Stelfox HT, Straus SE, Flemons WW, et al. Quality indicators in trauma care (Funding Reference #KRS-91770). University of Calgary: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2008-10-01 to 2009-09-30.

- 62.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ tools and resources for better health care. Research in Action, Issue 10. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/tools/toolsria.htm#assessment (accessed 7 Mar 2012) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.EndNote X5. New York, NY: Thomson Reuter, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caldwell K, Henshaw L, Taylor G. Developing a framework for critiquing health research: an early evaluation. Nurse Educ Today 2011;31:e1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McGlynn EA. Selecting common measures of quality and system performance. Med Care 2003;41(Suppl 1):I39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fan E, Laupacis A, Pronovost PJ, et al. How to use an article about quality improvement. JAMA 2010;304:2279–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoyt DB, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, Fortlage D, et al. An evaluation of provider-related and disease-related morbidity in a level I university trauma service: directions for quality improvement. J Trauma 1992;33:586–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis JW, Hoyt DB, McArdle MS, et al. The significance of critical care errors in causing preventable death in trauma patients in a trauma system. J Trauma 1991;31:813–18; discussion 818–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.