Abstract

Objectives

To examine the role of general practitioners (GPs) in HIV counselling and testing over a 22-year period.

Design

A dynamic cohort study.

Setting

General practices (N=42) participating in the Dutch Sentinel General Practice Network at Nivel with a nationally representative patient population by age, gender, regional distribution and population density.

Outcome measures

HIV-related consultations from 1988 to 2009 were recorded using a questionnaire in which patient's characteristics, interventions and test results were recorded. Trends over time and effects of urbanisation (3 categories) were assessed by multilevel analysis to control for clustering of observations within general practices.

Results

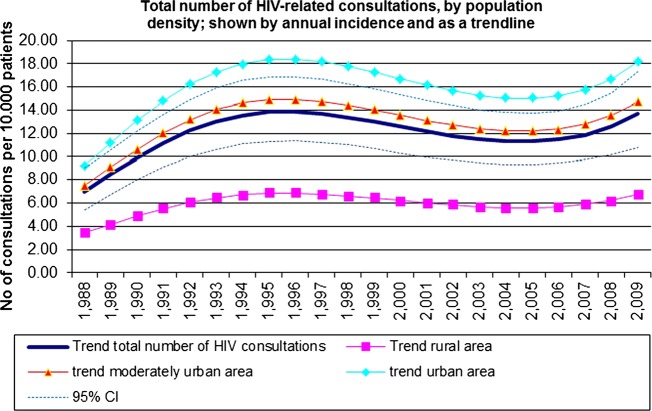

Time trend analyses show an increasing trend in HIV-related consultations and in the total number of HIV tests per 10 000 registered patients from 1988 to 1996, followed by a declining period and an increase again in the period 2007–2009. Over the whole period, the number of HIV-related consultations was highest in the urban areas with a maximum of 18 per 10 000 patients in 1996. The proportion of people high at risk, men who have sex with men, decreased. The proportion of HIV-related consultations initiated by the GPs increased from 11% in 1988 to 23% in 2009.

Conclusion

In this 22-year period, HIV-related consultations and provider-initiated HIV testing in the Dutch general practice have increased. More attention for sexual health in general practice is required that focuses on high-risk groups and on more routine testing in high prevalence areas.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Sexual Medicine, Infectious Diseases

Article focus

Have the number of HIV-related consultations and/or patient's characteristics changed over the years?

Does the propagation of active test and counselling policies in the Netherlands lead to more testing during HIV-related consultations and more initiative being taken by the GP related to HIV?

What trends in HIV-related consultations could be described considering a 22-year period (1988–2009)?

Key messages

In this 22-year period, an increasing trend in HIV-related consultations was found.

The number of HIV-related consultations was highest in urban areas and the increase was mainly observed in low-risk groups.

Provider-initiated HIV testing in Dutch general practice increased over the years and should focus on high-risk groups and more routine testing in high prevalence areas.

Introduction

Up until 1996, health providers in The Netherlands have pursued a reserved and reluctant policy with respect to testing for HIV.1 However, since 1999, WHO and the Health Council of the Netherlands are promoting an active HIV counselling and test policy.2 In sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, clients are now routinely tested for HIV, unless they explicitly oppose this procedure (opting out).3 4 As a result of this opt-out policy, HIV testing rates increased at STI clinics from 56% in 2004 to 97% in 2010.4 5 Similarly, Dutch general practitioners (GPs) are encouraged to play an active role in testing and counselling in the field of HIV. Despite the WHO active testing policy of over a decade now, research has revealed that testing rates in primary care remain low with substantial geographic differences in the intensity of testing even within countries.6 7 In Europe, there is still a proportion of 30–40% of HIV-positive cases that is not diagnosed with HIV because they have not been tested.8 In the Netherlands, it is estimated that 40% of HIV cases remain undiagnosed, while around 43% of the people are tested too late (<350 CD4 cells/mm3).9 10 According to the Dutch HIV Monitoring Foundation, there were 16 167 HIV patients in care in the Netherlands in 2012. With a percentage of 67%, men who have sex with men (MSM) are the main risk group for HIV. Of the registered HIV patients, 59% are Dutch nationals and 15% are sub-Saharan Africans. The number of new HIV diagnoses each year remains high with a reported number of 1100 diagnoses in 2011, which was similar to 2009 and 2010.9

In the Netherlands, people are registered with a general practice and the GP is the core primary healthcare provider.11 STI clinics are freely accessible but focus mainly on risk groups.5 6 A study on healthcare-seeking behaviour in the Netherlands has shown that of people with STI-related questions and/or symptoms, more than 60% consulted the GP, while only 20% visited an STI clinic.11 Therefore, the GP is in an excellent position to contribute to the prevention and control of HIV by active counselling and testing.3 12–15 In order to optimise general practice care related to HIV, this article reflects on the changes in policy of the GP regarding HIV-related consultations during a period of 22 years. Have the number of HIV-related consultations and/or patient's characteristics changed over the years? Does the propagation of active test and counselling policies in the Netherlands lead to more testing during HIV-related consultations and more initiative taken by the GPs related to HIV? Trends during a 22-year period (1988–2009) are described, focusing on the more recent years.

Methods

Data were retrieved from the Dutch Sentinel General Practice Network at Nivel, a network existing since 1970 and consisting of 59 Dutch GPs in 42 general practices. The patient population covers approximately 0.8% of the Dutch population and is nationally representative by age, gender, regional distribution and by distribution in population density.16 In addition, the network is designed to be nationally representative by type of practice, that is, solo practice, group practice or health centre. Ethical approval for the study was not necessary following Dutch law as the study used anonymous patient data collected for routine surveillance.

Data collection procedures

Since 1988, the Dutch Sentinel General Practice Network has recorded the incidence of HIV consultations of patients who were not (known to be) HIV positive.14 17 HIV-related consultations were recorded by GPs using the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) code B25 in patients’ electronic medical records. In addition, GPs recorded on a questionnaire patients’ characteristics and the interventions by the GP. From January 2008, this subject was integrated in a broader questionnaire concerning STIs. This questionnaire was completed for every consultation concerning STIs. The subject ‘fear of HIV’ became part of this questionnaire and was completed by each GP in case the patient raised questions about HIV, a suspicion of HIV, a fear of HIV or requested an appointment for an HIV test. Questions about who (ie, GP or patient) initiated discussing about or testing for HIV were included in the questionnaire. When a patient was tested, the test results were also reported. Diagnostics regarding the HIV status were performed by the regional laboratory nearest to the practice.

Data analysis

Outcome measures were: HIV consultation and HIV test per 10 000 registered patients; initiative for discussing HIV (GP or patient), initiative for testing HIV, HIV test request, sexual preference and HIV test result in percentages of the HIV consultations. The estimated mean numbers of HIV-related consultations, average proportions of patients and interventions were adjusted for clustering within the practice and urbanisation. The minimum and maximum values present the range within which 95% of the practice scores fall to illustrate the large differences between practices.

Data were analysed using PASW Statistics V.18.0 and MLwin V.2.02 software. Multilevel analyses were applied to adjust for large interpractice variation and skewed distribution. A multilevel (Poisson, logistic) regression was used to control for clustering of observations within practices. All participating general practices were included, including practices without HIV-related consultations. The time trend was estimated using a third-order polynomial for time, to allow for a potential non-linear trend. Urbanisation was categorised in: rural areas (<500 inhabitants/km2), urbanised rural municipalities (500–2500 inhabitants/km2) and big cities (>2500 inhabitants/km2). Beside these two effects (time trend and urbanisation), the interpractice variation, as estimated by the model, was used to calculate the 95% coverage interval, the interval supposedly including 95% of the practice averages in the population. It is important to notice that this interval can be much wider than the CI around the general average or the difference between urbanisation classes. This would mean that a large interpractice variation is observed that is not explained by the factors in the model.

Results

HIV-related consultations and patient characteristics

Since 1988, the number of HIV-related consultations in average Dutch general practices increased as shown from multilevel analyses adjusting for interpractice variation attributed to population density, from 7 per 10 000 patients in 1988 to 14 per 10 000 registered patients between 1994 and 1997, declining slightly to 13 per 10 000 patients in 2009 (figure 1). During the whole period (1988–2009), the incidence of HIV-related consultations was highest in practices established in large cities (>2500 addresses per square kilometre) when compared with practices in less densely populated areas with a large fluctuation over the years (p<0.01, figure 1). The time trend analysis shows an increasing consultation rate over time (p<0.001, figure 1). However, the interpractice variation is large, resulting in a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 31 contacts per GP per 10 000 registered patients per year (table 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in the number of HIV-related consultations per year in general practice per 10 000 patients in total with 95% CIs and by population density over the years 1988–2009 by a multilevel analysis.

Table 1.

Estimated mean number of HIV-related consultations, average proportions of patients and interventions with minimum value and maximum value covering 95% of the values of all practices adjusted for interpractice variation attributed to population density

| Mean | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV consultations (number per 10 000 patients) | 7.0 | 1.6 | 31.0 |

| Test request (number per 10 000 patients) | 3.4 | 0.8 | 14.9 |

| Gender (% male) | 58.2 | 47.0 | 68.6 |

| Sexual preference (% homosexual or bisexual) | 14.2 | 3.7 | 42.1 |

| Testing for HIV (% yes) | 52.1 | 21.1 | 81.5 |

| Test requests (% yes) | 64.5 | 37.2 | 84.8 |

| Initiative in discussing HIV (% GP) | 11.1 | 3.0 | 33.6 |

| Test results (% positive) | 0.5 | 0.1 | 4.4 |

| Initiative testing for HIV (% GP) | 10.7 | 3.9 | 25.5 |

GP, general practitioner; max, maximum; min, minimum.

In the first year, 1988, patients who consulted their GP for HIV were mainly men (58%). During the following years, trend analysis showed an increasing number of women consulting their GP. The mean age of people who consulted their GP regarding HIV was 32 years (range 30–37 years). On average, men consulting the GPs were somewhat older compared with women (mean difference of 4 years in 2009, not in the table).

The majority of people who consulted their GP for HIV were heterosexuals. However, over the whole period, there is a large variation between practices, with a minimum of 4% homosexuals or bisexuals and a maximum of 42% homosexuals or bisexuals per general practice (table 1). In 1988, more than 80% of the people were heterosexual: in 2008 and 2009, this was over 90%. Although MSM are considered the major risk group for HIV infection in the Netherlands, the proportion of this high-risk group consulting the GPs for HIV has decreased over the years.

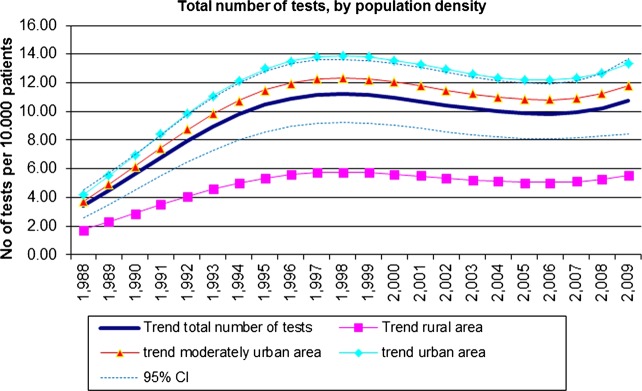

Discussing and testing for HIV

An analysis of the number of HIV tests per 10 000 registered patients in total and by population density by multilevel analysis showed a steep rise in the number of tests in the 90s, some decline in the years thereafter and an increase again in the years 2007–2009 (an increase from 53% of patients consulting for HIV being tested in 1988 to 88% in 2009, figure 2). The tests were more often requested in urban areas than in rural areas (figure 2), and testing was more often initiated by the GPs in the later years than in the earlier years. The odds of receiving an HIV-test is also highest in urban areas, but the proportion undergoing an HIV-test following an HIV-related consultation is slightly higher in rural areas than in urban areas.

Figure 2.

Trends in the number of HIV tests per 10 000 registered patients in general practice per year in total and by population density over the years 1988–2009 by a multilevel analysis.

Discussing HIV during GP consultation was mostly initiated by the patient (77–93% over the whole period). However, although there is no significant trend over the years, the proportion of HIV-related consultations initiated by the GPs increased from 11% in 1988 to 23% in 2009. A large interpractice variance exists in the number of requested tests per 10 000 registered patients, the percentage of HIV tests per HIV-related consultation as well as the GP's initiative in discussing and testing for HIV that cannot be attributed to population density (table 1).

The percentage of positive test results in this GP network remained low over the whole period with a mean of 1% per year, varying from zero positive results in the initial years to several cases/year in the later years in homosexual and heterosexual patients.

Discussion

This study shows a significant trend towards more consultations and more testing related to HIV in the Dutch general practice over a 22-year period, as well as a trend towards consulting and testing by populations less at risk for HIV. The percentages of GP-initiated discussion and testing rates of HIV were higher in the last 2 years. Overall, the results show a large variation between general practices and a threefold higher number of HIV consultations in urban areas compared with rural areas. The odds of receiving an HIV test are also the highest in urban areas, but the proportion undergoing an HIV test following an HIV-related consultation is slightly higher in rural areas than in urban areas. An explanation could be that in urban areas, people still have the opportunity to visit STI clinics which attract more ‘at-risk’ populations and offer tests anonymously, while in rural areas these clinics are less available.

While at the start of the study (1988) more MSM consulted the GP, over the last 3 years, a majority of heterosexual women consulted the GPs, suggesting a shift towards testing more people at low risk. Over the whole period, the percentage of positive HIV tests remained low in the Dutch general practice.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study of HIV-related consultations carried out in a network of general practices is nationally representative by age, gender, geographical distribution and distribution in population density. The study is representative of the average Dutch general practice patient population, especially due to the multilevel Poisson analysis techniques used with adjustment for age, gender, interpractice variation, skewed distribution and population density. The study results cannot be extrapolated to the general population as some patients prefer to consult STI clinics, so our figures underestimate the total number of HIV consultations in the general population, especially in urban areas. Also, the study cannot be directly compared with other studies not applying multilevel techniques as the adjustment for skewed distribution decreases the mean levels.

From the year 2008, the questionnaire regarding ‘fear of HIV’ used from 1988 till 2007 was integrated into a broader questionnaire on the subject of ‘fear of STIs’. This may have influenced the study results in the last two study years presented in this article, although all the main questions from the existing questionnaire were integrated into the new questionnaire. In addition, the total number of requested tests per 10 000 patients registered in the practices also increased over the years, and this number is not influenced by embedding the subject in a broader STI subject. A question on self-reported ethnicity was admitted in the questionnaire from 2008 onwards, but as it was not applied in a uniform way during the total study period, we decided not to include analyses on migrants in this study. From the Dutch surveillance data, we know that in 2011, 24% of Dutch patients at STI clinics originated from HIV endemic areas.18

Comparison with existing literature

During the first years of this study, the number of consultations regarding HIV increased rapidly and the GP is generally the patient’s first choice for HIV-related consultation as well as testing in the Netherlands.19 This is in contrast to a study in the UK revealing low HIV-testing rates in primary care and showing patients’ preference for consulting other facilities like genitourinary medicine clinics.7 20 Another study in the UK indicates that patients may have concerns about GPs’ knowledge related to HIV and doubts about confidentiality, disclosure and discrimination in general practice were reported too.21

Our study shows that most people who consulted their GP regarding HIV belong to the low-risk group. The Dutch surveillance data reveal that STI centres are more often consulted by people at high risk, like MSM (36% of male visitors in 2010), migrants from HIV endemic areas (24% of all attendees), sex workers (10% of women) and clients of sex workers (8% of men).18 19

Our study finding of a higher HIV-related consultation frequency in urban areas is consistent with another Dutch trend analysis of test requests in Amsterdam in the period 1989–1996, showing an increasing trend over time.22

Implications for future research or clinical practice

In Europe, 30% of HIV-infected people overall are not aware of their status because they have never been tested.23 In the Netherlands, the proportion of undiagnosed HIV-infected people is estimated at 40%.10 Early treatment is beneficial both from a patient's perspective and from a public health point of view owing to decreased infectivity when HIV is treated well. Active testing in STI centres resulted in an increased proportion of people tested from 56% in 2004 to 97% in 2010 and the percentage of MSM who reported having been tested increased from 42% in 2000 to 75% in 2010.24 25 However, despite several years of increased attention for active HIV testing especially among certain ethnic minorities, a large proportion of infected people are still undiagnosed or diagnosed at a late stage of disease, showing the limited success of the present approach in certain groups.18

Our study showed that discussing HIV during GP consultation was mostly initiated by the patient, although the proportion of HIV-related consultations initiated by the GP increased from 11% in 1988 to 23% in 2009. The large interpractice variation in the number of requested tests per 10 000 registered patients and GPs’ reservation to discuss and test for HIV in our study suggest that giving sexual health a more prominent place in general practice would be beneficial to improve HIV case detection and approach HIV-positive patients who may not come forward easily at present.8

In the Netherlands, almost all inhabitants are registered in a general practice and the GP plays an important potential role to promote testing and early detection, especially for those at risk not reached with current ‘opt out’ policies at STI clinics and test campaigns. The guidelines advise a low threshold on HIV testing, especially when unexplained signs and symptoms are presented, such as fatigue, suspicion of Epstein-Barr virus infection, lymphadenopathy and thrombocytopenia. A more proactive role of the GP is recommended, but not well defined. Implementation of provider-initiated testing in primary care is a matter of balancing between risk estimation, cultural barriers and improving professional competence, for instance in knowing the patient's sexual identity. Other studies support the idea of a more proactive role of the GP, and other countries endorse provider-initiated testing in general practice. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) strongly recommends provider-initiated testing based on the UK national guidelines for HIV testing, and advises testing of all new patients who register in practices in areas where HIV prevalence exceeds 0.2%. NICE provides guidance on how to better implement testing among MSM and persons from HIV endemic countries.26 27 Another suggestion is routine discussion of HIV risk during an STI-related consultation and integrating HIV testing with other STI screening.7 Promoting proactive screening in general practice for patients not presenting with STI-related questions or symptoms presents challenges and ethical considerations. In addition, the tendency of low-risk groups to be screened more frequently may collide with evidence-based medicine. A prerequisite for focusing on high-risk groups is positive attention for sexual health in general practice.6

Conclusion

An increase in HIV-related consultations and more frequent provider-initiated testing over the past 20 years implies an improvement in the Dutch fight against HIV. Nevertheless, provider-initiated testing and communication about sexual health in primary care need more attention. Open communication about risk for HIV and how to prevent possible transmission may in itself modify risk behaviour. This requires excellent communication skills, an open attitude and adequate knowledge of HIV and its early symptoms that need to be developed and maintained by GPs and postgraduate training.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the general practitioners from the Dutch Sentinel General Practice Network for their contributions to the study. We thank Mrs M Heshusius-Valen for her crucial role in the data collection process.

Footnotes

Contributors: GD and JvB conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. SD, PS and GD were responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. SD, IB, PS and GD provided input for the data analysis. SD, GD and PS prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and it was then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. GD and IB were responsible for data acquisition. SD, PS, IB, GD and JvB contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by the Ministry of Health and by the non-profit organisation ‘STI-AIDS’ The Netherlands.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Coutinho R. Vergeet hiv in Nederland niet. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2007;151:2645–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, HIV/AIDS Department Priority interventions HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in the health sector (2010 version). Geneva:WHO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donker GA, Wolters I, van Bergen JEAM. Huisartsen moeten risicogroepen testen op hiv. Huisarts en Wetenschap 2008;51:419 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dukers-Muijrers HTM, Heijman RLJ, Van Leent EJM, et al. Hoog tijd voor brede toepassing van ‘opting-out’-strategie bij hiv-tests. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2007;151:2661–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Broek IVF, Verheij RA, van Dijk CE, et al. Trends in sexually transmitted infections in the Netherlands, combining surveillance data from general practices and sexually transmitted infection centers. BMC Fam Pract 2010;5:11–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Bergen JEAM, Kerssens J, Schellevis F, et al. Prevalence of STI related consultations in General Practice: results from the second Dutch National Survey of General Practice. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:104–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadler KE, Low N, Mercer CH, et al. Testing for sexually transmitted infections in general practice: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2010;667 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/667 (accessed 14 Mar 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Bergen JEAM. Normalizing HIV testing in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract 2012;18:133–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stichting HIV monitoring 2012, visited: 9 January 2013. http://www.hiv-monitoring.nl/index.php/ (accessed 14 Mar 2012).

- 10.Van Veen MG, Presanis AM, Conti S, et al. National estimate of HIV prevalence in the Netherlands: comparison and applicability of different estimation tools. AIDS 2011;25:229–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Bergen JEAM, Kerssens JJ, Schellevis FG, et al. Sexually transmitted infection health-care seeking behaviour in the Netherlands: general practitioner attends to the majority of sexually transmitted infection consultations. Int J Sex Transm Dis AIDS 2007;18:374–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koedijk FDH, Vriend HJ, van Veen MG, et al. Sexually transmitted infections including HIV, in the Netherlands in 2008. Annual STI-report RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/210261005.html (accessed 14 Mar 2012).

- 13.Kerssens JJ. Vragen aan de huisarts over HIV en AIDS, van 1998–2004. SOAIDS 2005;2:8–9 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerssens JJ, Peters L. Angst voor AIDS: hulpvragen bij de huisarts in de periode van 1988 tot en met 2004. Utrecht: Nivel, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross JD, Goldberg DJ. Patterns of HIV testing in Scotland: a general practitioner perspective. Scott Med J 1997;42:108–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donker GA. Continuous Morbidity Registration Dutch Sentinel Practice Network 2009. Annual report Utrecht: Nivel, 2010. http://www.nivel.nl/peilstations (accessed 23 May 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wigersma L. Decline in the incidence of HIV test requests in general practices in Amsterdam after 1992. Genitourin Med 1997; 73:324–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trienekens SCM, Koedijk FDH,, Broek van den IVF, et al. Sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, in the Netherlands in 2011, Annual STI-report RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/210051001/2012 (accessed 23 May 2012).

- 19.Vriend HJ, Koedijk FDH, van Veen MG, et al. Sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, in the Netherlands in 2010. Annual STI-report, Bilthoven, The Netherlands: RIVM, 2011. http//rivm.nl/Wetenschappelijk/Rapporten/2011/juni (accessed 23 May 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans HER, Mercer CH, Rait G, et al. Trends in HIV testing and recording of HIV status in the UK primary care setting: a retrospective cohort study 1995–2005. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:520–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard MA. Time to improve HIV testing and recording of HIV diagnosis in UK primary care. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ros CC, Kerssen JJ, Foets M, et al. Trends in HIV-related consultation in Dutch general practice. Utrecht, Nivel, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamers FF, Phillips AN. Diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV-infected populations in Europe. HIV Med 2008;9(Suppl. 2):6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schorer Schorer Monitor 2010: regiorapport. Amsterdam, Netherlands: The Municipal Health Council of Amsterdam, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiripinda I, Van Eerdewijk A. Facing HIV in the Netherlands: lived experiences of migrants living with HIV. Amsterdam: Pharos, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood H, Colver H, Stewart E, et al. Increasing uptake of HIV tests in men who have sex with men. Practitioner 2011; 255:25–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulland A. Test all patients in high prevalence areas for HIV, says NICE. BMJ 2011;342:d1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.