Summary

Background and objectives

This study aimed to evaluate dialysis and transplant outcomes of patients with ESRD secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

All ESRD patients who commenced renal replacement therapy in Australia and New Zealand between 1996 and 2010 were included. Outcomes were assessed by Kaplan–Meier, multivariable Cox regression, and competing-risks regression survival analyses.

Results

Of 36,884 ESRD patients, 228 had microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and 221 had granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Using competing-risks regression, compared with other causes of ESRD, MPA patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.89; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.73–1.08; P=0.24) and GPA patients (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.74–1.19; P=0.62) experienced comparable survival on dialysis. Forty-six MPA patients (21%) and 47 GPA (20%) patients received 98 renal allografts. Respective 10-year first graft survival rates in MPA, GPA, and non-AAV patients were 50%, 62%, 70%, whereas patient survival rates were 68%, 85% and 83%, respectively. Compared with non-AAV patients, MPA transplant recipients had higher risks of graft failure (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.07–3.25; P=0.03) and death (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.02–3.69; P=0.04), whereas GPA transplant recipients experienced comparable renal allograft survival (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.43–1.93; P=0.81) and patient survival (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.23–2.27; P=0.58). AAV recurrence was observed in two renal allografts (2%).

Conclusions

Compared with ESRD patients without AAV, those with GPA have comparable renal replacement therapy outcomes, whereas MPA patients have comparable dialysis survival but poorer renal transplant allograft and patient survival rates.

Introduction

ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a small vessel vasculitis, which includes granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (1), and Churg–Strauss angiitis (CSA) (2,3). The incidence of AAV has been reported to range between 4.6 and 21.8 per million population (4–8), is similar between GPA (2.1–10.8 per million) and MPA (2.5–7.9 per million) (6,7,9), is more common in males than females (5), and shows a clear increase with age, peaking in those aged 65–74 years (60.1 per million). Untreated, AAV has a 1-year mortality rate of 80% (10). After standard treatment with cyclophosphamide and steroids, the rates of ESRD and death at 5 years have been reported to be 28% and 34%, respectively (11). In other series, ESRD has been reported to occur in 9%–20% of patients at 1 year (9,12–16).

Unfortunately, the outcomes of patients with ESRD secondary to AAV after commencement of renal replacement therapy (RRT) have been subject to limited investigation. A recent report by the Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network included 136 patients with ESRD secondary to AAV, but subsequently excluded 43 patients who had no clinical information after starting dialysis (17). The other limitations of this study, as reported by the authors, included retrospective Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Scoring, incomplete data on the causes of death, and incomplete reporting of serious infections. Other studies have similarly been limited by small patient numbers and sparse clinical information (18–21).

The aim of this study was to evaluate dialysis patient survival, renal function recovery, renal allograft survival, and renal transplant patient survival in patients with ESRD secondary to MPA or GPA in the Australian and New Zealand dialysis populations, using data from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) registry.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

All patients with ESRD enrolled in the ANZDATA Registry who commenced RRT between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2010 were included in the study. ANZDATA collects data on patients whose ESRD is considered irreversible by the attending nephrologist, rather than representing AKI. Demographic and clinical data were collected throughout the calendar year by medical and nursing staff in each renal unit and submitted every 6 months to the ANZDATA Registry until 2005 and then annually thereafter. Patients with a primary renal diagnosis of GPA (Wegener’s granulomatosis) or MPA (1) comprised the AAV group in this study, and were compared with each other and with the remainder of the cohort (non-AAV group). Recorded primary renal diagnosis (MPA, GPA, or other) was determined by each patient’s attending nephrologist based on clinical picture, laboratory investigations, and/or renal biopsy. Dialysis and transplant eras were determined by the following dialysis and transplant commencement dates, respectively: January 1, 1996–December 31, 2000; January 1, 2001–December 31, 2005; and January 1, 2006–December 31, 2010. Ethical approval for the use of registry data was obtained from the Princess Alexandra Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee. The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul, as outlined in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.

The primary outcomes examined were patient survival on dialysis (censored for renal function recovery, loss to follow-up, renal transplantation, and end of study), renal transplant patient survival (censored for loss to follow-up and end of study), and renal allograft survival in which death with a functioning allograft was treated as an event (censored for loss to follow-up and end of study). Recovery of dialysis-independent renal function was considered to have occurred if the treating renal unit had recorded that the patient had recovered renal function and completed dialysis therapy. The onset of recovery was defined as the date of the last dialysis treatment. In order to avoid including patients with renal recovery due to AKI (non-ESRD), only patients remaining on dialysis for >90 days were evaluated in the renal recovery analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Results were expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, mean ± SD for continuous normally distributed variables, and median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables that were not normally distributed. ESRD patients with GPA, MPA, or without AAV were compared using chi-squared tests, one-way ANOVA, or Kruskal–Wallis H tests, depending on data distribution. Time-to-event analyses of patients with MPA, GPA, and non-AAV ESRD were evaluated by Kaplan–Meier and multivariable Cox proportional hazards survival analyses. In light of the possibility of informative censoring due to differential rates of transplantation or renal recovery between patients with MPA, GPA, and non-AAV, multivariable competing-risks regression was additionally performed for analysis of dialysis survival (22,23). For the outcome of renal recovery, death on dialysis and renal transplantation were analyzed as competing events. The covariates included in the multivariable Cox or competing-risks models were age, sex, racial origin, ESRD cause, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (never, former, or current), comorbidities (chronic lung disease, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular disease), late referral (defined as commencement of dialysis within 3 months of referral to a nephrologist), and dialysis era or transplant era (as well as donor type [living or deceased] and time from dialysis commencement to renal transplantation for renal transplant analyses). For the reported comorbidities, which represented clinical diagnoses by the patients’ attending nephrologists, we included “suspected” with “yes” for analyses. Dialysis survival analyses were also performed within AAV patients alone (MPA versus GPA). First-order interaction terms were examined between primary disease (GPA, MPA, or non-AAV) and all other significant covariates in all Cox proportional hazards model. Statistical analysis was performed using the PASW Statistics for Windows release 18.0 (SPSS Inc., North Sydney, Australia) and Stata/SE version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) software packages. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2010, 36,884 individuals started RRT for ESRD. Of these, 221 patients (0.6%) had ESRD secondary to GPA and 228 (0.6%) had ESRD secondary to MPA. The baseline characteristics of ESRD patients with MPA, GPA, and non-AAV are displayed in Table 1. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between MPA and GPA patients, except that MPA patients were more likely to be former or current smokers (P=0.02).

Table 1.

Characteristics of all patients with ESRD secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis or other causes in Australia and New Zealand during 1996–2010

| Characteristic | Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (n=221) | Microscopic Polyangiitis (n=228) | Other ESRD (n=36,435) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 60.7±16.4 | 61.8±15.4 | 58.0±16.7 | <0.001 |

| Age category (yr) | 0.05 | |||

| 0–9 | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 312 (1) | |

| 10–19 | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 584 (2) | |

| 20–29 | 9 (4) | 7 (3) | 1570 (4) | |

| 30–39 | 12 (5) | 9 (4) | 2800 (8) | |

| 40–49 | 24 (11) | 22 (10) | 4921 (14) | |

| 50–59 | 39 (18) | 38 (17) | 7239 (20) | |

| 60–69 | 54 (24) | 64 (28) | 8565 (24) | |

| 70–79 | 63 (29) | 69 (30) | 8212 (23) | |

| ≥80 | 15 (7) | 14 (6) | 2232 (6.1) | |

| Male | 153 (61.1) | 153 (67.1) | 21,677 (59.5) | 0.06 |

| Racial origin | <0.001 | |||

| European | 209 (95) | 214 (94) | 26,746 (73) | |

| ATSI | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2736 (8) | |

| MPI | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 3784 (10) | |

| Asian | 6 (3) | 4 (2) | 1824 (5) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 1345 (4) | |

| RRT era | 0.23 | |||

| 1996–2000 | 60 (27) | 71 (31) | 9730 (27) | |

| 2001–2005 | 85 (39) | 75 (33) | 12,241 (34) | |

| 2006–2010 | 76 (34) | 82 (36) | 14,464 (40) | |

| Ever smoked | 0.13 | |||

| Current | 19 (9) | 34 (15) | 4747 (13) | |

| Former | 88 (40) | 104 (46) | 14,409 (40) | |

| Never | 114 (52) | 90 (40) | 17,271 (47) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (0) | |

| Hypertension | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 104 (47) | 112 (49) | 17,670 (48) | |

| No | 31 (14) | 27 (12) | 2720 (8) | |

| Missing | 86 (39) | 89 (39) | 16,045 (44) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 34 (15) | 33 (14) | 14,771 (41) | |

| No | 187 (85) | 195 (86) | 21,664 (59) | |

| Chronic lung disease | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 59 (27) | 54 (24) | 5746 (16) | |

| No | 162 (73) | 174 (76) | 30,689 (84) | |

| Coronary artery disease | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 61 (28) | 64 (28) | 14,242 (39) | |

| No | 160 (72) | 164 (72) | 22,192 (61) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 39 (18) | 29 (13) | 9336 (26) | |

| No | 182 (82) | 199 (87) | 27,098 (74) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.03 | |||

| Yes | 18 (8) | 24 (10) | 5402 (15) | |

| No | 203 (92) | 204 (90) | 31,032 (85) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8±5.3 | 25.5±5.2 | 27.1±6.4 | <0.001 |

| First RRT | <0.001 | |||

| Hemodialysis | 186 (84) | 181 (79) | 25,626 (70) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 33 (15) | 43 (19) | 9627 (26) | |

| Renal transplant | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 1182 (3) | |

| Renal biopsy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 210 (95) | 219 (96) | 11,198 (31) | |

| No | 10 (5) | 8 (4) | 24,397 (67) | |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 840 (2) | |

| Follow-up (years) | 3.0 (1.0–5.8) | 3.3 (1.3–5.7) | 3.1 (1.3–5.9) | 0.08 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (range). ATSI, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; MPI, Maori and Pacific Islander; RRT, renal replacement therapy; BMI, body mass index.

Patient Survival on Dialysis

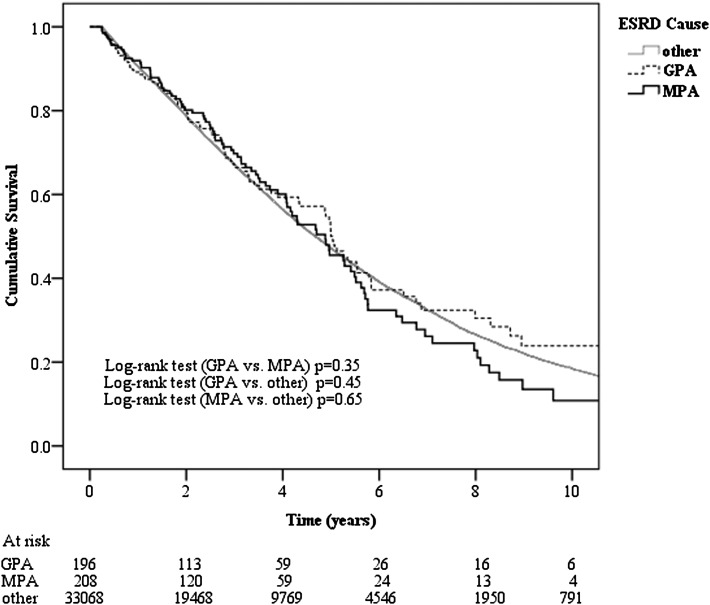

A total of 35,253 non-AAV, 224 MPA, and 219 GPA patients initiated RRT by dialysis. The first-year survival rates were 88% (n=3990 deaths), 89% (n=22 deaths), and 84% (n=33 deaths), respectively (P=0.93). Excluding patients who were on dialysis <90 days (GPA, n=23; MPA, n=16; non-AAV, n=2185), the median survival of patients with MPA (5.24 years; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 4.58–5.90 years) was comparable with that of GPA patients on dialysis (6.11 years; 95% CI, 5.25–6.97 years; P=0.35) and patients with other causes of ESRD (5.79 years; 95% CI, 5.71–5.86 years; P=0.65) (Figure 1). Respective survival rates in the three groups were 92%, 89%, and 91% at 1 year; 70%, 67%, and 67% at 3 years; and 46%, 50%, and 47% at 5 years. Using multivariable Cox proportional hazards model analysis, neither MPA (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.98; 95% CI, 0.80–1.20; P=0.80) nor GPA (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.75–1.15; P=0.51) was independently associated with patient survival on dialysis compared with non-AAV patients after adjusting for other confounding factors. When renal transplant and renal function recovery were considered as competing risks in multivariable competing-risks regression, neither MPA (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.73–1.08; P=0.24) nor GPA (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.74–1.19; P=0.62) was associated with dialysis mortality compared with non-AAV patients.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves in dialyzed ESRD patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and other causes of ESRD in Australian and New Zealand during 1996–2010.

When only patients with AAV were considered, multivariable Cox proportional hazards model analysis showed that patients with MPA experienced comparable survival on dialysis compared with patients with GPA (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.77–1.40; P=0.94). Death on dialysis was only predicted by older age (HR per decade, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.25–1.73; P<0.001) and initiation of dialysis in an earlier era (P=0.02) (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 0.91–2.57 for January 1, 1996–December 31, 2000; and HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.21–3.26 for January 1, 2001–December 31, 2005 compared with those who initiated dialysis from January 1, 2006–December 31, 2010) after adjusting for other confounding factors.

The causes of dialysis death among MPA (n=96), GPA (n=85), and non-AAV patients (n=15,233) were generally comparable, except for a higher probability of dialysis withdrawal in MPA patients, as follows: cardiac (15%, 17%, and 19%, respectively; P=0.56), infectious (6%, 8%, and 6%;P=0.54), vascular (8%, 6%, and 6%; P=0.39), dialysis withdrawal (9%, 3%, and 4%; P=0.04), malignancy (6%, 3%, and 3%; P=0.07), and other (1%, 3%, and 3%; P=0.59).

Recovery of Renal Function

In dialysis patients remaining on dialysis >90 days (GPA, n=196; MPA, n=208), recovery of dialysis-independent renal function occurred in 10 MPA patients (5%) and 6 GPA patients (3%). Compared with patients with GPA, patients with MPA had a comparable renal function recovery rate (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 0.59–4.41; P=0.36). The median times from initiation of dialysis to renal recovery were 0.87 years (IQR, 0.34–1.11) for MPA patients and 1.54 years (IQR, 0.68–4.40) for GPA patients. Three GPA patients (50%) and two MPA patients (20%) never returned to RRT by the end of study on December 31, 2010. One MPA patient (10%) and one GPA patient (17%) died after recovery of renal function after 1.75 and 4.09 years, respectively. Seven MPA patients (70%) and two GPA patients (33%) returned to dialysis after median periods of 0.95 years (IQR, 0.37–2.67) and 0.95 years (IQR, 0.27–1.63), respectively.

Renal Transplant Graft Survival

Forty-six MPA patients (21%) and 47 GPA patients (20%) received 98 renal allografts during the study period compared with 8193 non-AAV ESRD patients (22%) who received 8453 renal allografts. The baseline characteristics of the three groups are shown in Table 2 and were generally similar. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between MPA and GPA patients except that MPA patients were older than GPA patients (P=0.05).

Table 2.

Characteristics of all renal transplant patients with ESRD secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis or other causes in Australia and New Zealand during the period 1996–2010

| Characteristic | Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (n=47) | Microscopic Polyangiitis (n=46) | Other ESRD (n=8193) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 46.5±14.5 | 52.8±15.8 | 44.1±15.4 | <0.001 |

| Male | 33 (70) | 28 (61) | 5076 (62) | 0.50 |

| Racial origin | 0.08 | |||

| European | 45 (96) | 44 (96) | 6722 (82) | |

| ATSI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 241 (3) | |

| MPI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 341 (4) | |

| Asian | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 524 (6) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 365 (5) | |

| Transplant era | 0.41 | |||

| 1996–2000 | 15 (32) | 17 (37) | 1543 (19) | |

| 2001–2005 | 24 (51) | 18 (39) | 2937 (36) | |

| 2006–2010 | 8 (17) | 11 (24) | 3713 (45) | |

| Ever smoked | 0.56 | |||

| Current | 3 (6) | 7 (15) | 873 (11) | |

| Former | 14 (30) | 18 (39) | 2423 (30) | |

| Never | 30 (64) | 21 (46) | 4890 (60) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (0) | |

| Hypertension | 0.64 | |||

| Yes | 27 (57) | 29 (63) | 4879 (60) | |

| No | 8 (17) | 4 (9) | 859 (10) | |

| Missing | 12 (26) | 13 (28) | 2455 (30) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.04 | |||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 3 (7) | 1323 (16) | |

| No | 44 (94) | 43 (94) | 6870 (84) | |

| Chronic lung disease | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 6 (13) | 9 (20) | 352 (4) | |

| No | 41 (87) | 37 (80) | 7841 (96) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.57 | |||

| Yes | 6 (13) | 3 (7) | 749 (9) | |

| No | 41 (87) | 43 (94) | 7444 (91) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.19 | |||

| Yes | 5 (11) | 1 (2) | 458 (6) | |

| No | 42 (89) | 45 (98) | 7735 (94) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.40 | |||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 256 (3) | |

| No | 44 (94) | 44 (96) | 7937 (97) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9±4.0 | 26.1±4.6 | 25.3±5.2 | 0.68 |

| Late referral | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 13 (28) | 18 (39) | 1338 (16) | |

| No | 34 (72) | 28 (61) | 6808 (83) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 47 (1) | |

| Donor type | 0.76 | |||

| Deceased | 28 (57) | 25 (51) | 4748 (56) | |

| Living | 2 (43) | 24 (49) | 3694 (44) | |

| Subsequent grafts | 0.76 | |||

| Second | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 254 (3) | |

| Third | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (0) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (range). ATSI, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; MPI, Maori and Pacific Islander; BMI, body mass index; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

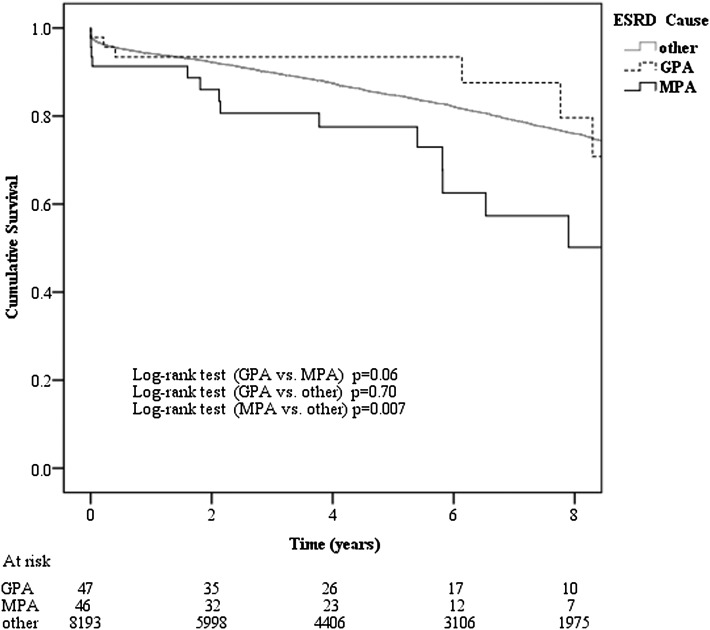

A total of 1524 first grafts in the non-AAV group (19%) and 21 in the AAV group (23%) failed during the study period, either as a result of loss of function or patient death. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier curve for first graft survival. Graft survival in MPA patients was significantly lower than non-AAV patients (P=0.01) and tended to be worse than GPA patients (P=0.06). Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model analysis showed that MPA transplant patients had a higher risk of graft failure compared with non-AAV patients (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.07–3.25; P=0.03), whereas GPA patients did not (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.43–1.93; P=0.81) after adjusting for age, sex, racial origin, BMI, smoking status, comorbidities status, late referral, transplant era, donor type, and time from dialysis commencement to renal transplantation The respective 5-year graft survival rates in MPA, GPA, and non-AAV patients were 82%, 96%, 85%, whereas 10-year graft survival rates were 50%, 62%, and 70%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier first graft survival curves in transplanted ESRD patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and other causes of ESRD in Australia and New Zealand during 1996–2010.

There was no significant difference in the causes of renal allograft failure between the AAV (n=10) and non-AAV groups (n=1002). The causes of renal allograft failure were chronic allograft nephropathy (50% versus 45%, respectively), acute rejection (0% versus 6%), hyperacute rejection (0% versus 1%), renal artery thrombosis (10% versus 5%), renal vein thrombosis (20% versus 5%), GN (10% versus 8%), and other (10% versus 30%) (P=0.45). Two allografts (2%) in the AAV group experienced recurrence of original disease. One patient with GPA experienced GPA recurrence in the allograft 6.65 years after transplantation resulting in allograft failure 7.76 years after transplantation. One patient with MPA experienced MPA recurrence 4.79 years after transplantation but still had a functional allograft 7.46 years after transplantation, as of December 31, 2010.

Renal Transplant Patient Survival

MPA patient survival after renal transplantation was significantly inferior to that of GPA patients (P=0.04) and non-AAV patients (P=0.003) (Figure 3). Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model analysis showed that MPA transplant patients had a significantly higher risk of death compared with non-AAV patients (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.02–3.69; P=0.04), whereas GPA transplant patients did not (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.23–2.27; P=0.58) after adjusting for age, sex, racial origin, BMI, smoking status, comorbidities, late referral, transplant era, donor type, and time from dialysis commencement to renal transplantation. The respective 5-year renal transplant patient survival rates in MPA, GPA, and non-AAV were 82%, 96%, and 92%, whereas the 10-year rates were 68%, 85%, and 83%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier patient survival curves in transplanted ESRD patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and other causes of ESRD in Australia and New Zealand during 1996–2010.

The causes of death in the MPA (n=10), GPA (n=3), and non-AAV groups (n=825) were generally comparable, except for a significantly higher proportion of cardiac and malignant deaths in the MPA group, as follows: cardiac (11%, 2%, and 3%; P=0.001), vascular (2%, 0%, and 1%; P=0.50), infectious (0%, 2%, and 2%; P=0.61), withdrawal (2%, 0%, and 1%; P=0.50), malignancy (7%, 0%, and 2%; P=0.03), and other (0% 2% and 1%; P=0.55).

Discussion

This study is the largest multicenter investigation to date looking at the outcomes of patients with ESRD secondary to AAV. Our study observed that, compared with ESRD patients without AAV, those with MPA had a comparable dialysis outcome but lower renal allograft survival and postrenal transplant patient survival, whereas those with GPA had comparable dialysis and renal transplant outcomes. Furthermore, MPA patients had lower post-transplant survival than GPA patients.

The observed 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates of dialysis patients with MPA (92%, 70%, and 46%, respectively) or GPA (89%, 67%, and 50%) in this study were comparable with or superior to what has been reported in previous studies (16–18). In a retrospective, single-center, observational cohort study of 59 patients with ESRD secondary to AAV (GPA, n=23; MPA, n=33; CSA, n=3), actuarial survival rates at 1 and 5 years were 82% and 59%, respectively (16). Moreover, similar to our study, no significant difference was observed between the dialysis survival of patients with MPA and those with GPA (P=0.13). However, the small sample size limited the precision of survival estimates and the single-center design limited generalizability. A larger inception cohort study of AAV patients, which included 93 AAV patients with ESRD, reported 1-year and 5-year survival rates of 77% and 28%, respectively (17). However, neither of the aforementioned studies reported outcomes compared with ESRD controls. This issue was addressed by an earlier multicenter, retrospective study of 191 patients with ESRD secondary to vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa [PAN], n=60; GPA, n=131), which observed 33-month survival rates of 62% in PAN patients and 58% in GPA patients, comparable with that of the nondiabetic control population (18). However, in contrast to our study in which recovery occurred in 5% of MPA, 3% of GPA, and 1.5% of non-AAV patients, this event was observed in 10% of PAN and 6% of GPA patients (control data were not provided). The apparent disparity in results may relate to differences in the stringency of the definition of ESRD between the two groups, such that more cases of AKI may have been included in the latter study. Moreover, the earlier study was published before the Chapel Hill Consensus on nomenclature of systemic vasculitis (3), such that the PAN group included classic PAN (with aneurysmal inflammation of medium-sized and small arteries) in addition to MPA.

In this study, renal transplant graft survival in GPA patients was comparable with non-AAV patients but superior to MPA patients. In contrast, the Collaborative Transplant group reported that the 10-year survival of 378 GPA patients who received deceased donor renal transplants was superior compared with that in 14,482 polycystic kidney disease patients (80% versus 70.9%, respectively; P<0.05) (24). Shen et al. similarly reported superior graft survival (adjusted HR, 0.711), patient survival (adjusted HR, 0.631), and functional graft survival (adjusted HR, 0.625) in 919 GPA ESRD renal transplant recipients compared with ESRD renal transplant recipients from other causes (1). However, in this study, the GPA cohort had a higher percentage of Caucasians, lower panel-reactive antibody levels, fewer HLA-D–related mismatches, and more living donors. Most importantly, the GPA cohort had a significantly lower proportion of patients with diabetes mellitus. When adjusted for recipient diabetes status, patient and graft survival were similar between the two groups. However, it should be noted that the numbers of patients with MPA and GPA who received renal transplants in this study were relatively small, which made it difficult to conclude with certainty that the graft survival in these two groups was actually different.

The strengths of this study included its very large sample size and inclusiveness. We included all patients with AAV receiving RRT in Australia and New Zealand during the study period, such that a variety of centers were included with varying approaches to the treatment of AAV and ESRD. This greatly enhanced the external validity of our findings. These strengths should be balanced against the study’s limitations, which included limited depth of data collection. ANZDATA does not collect important information, such as ANCA profile, detailed renal biopsy results, onset of AAV, date of disease remission, severity of comorbidities, patient compliance, and individual unit management protocols (including plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy). Even though we adjusted for a large number of patient characteristics, the possibility of residual confounding could not be excluded. It is also possible that some of the patients considered to have irreversible ESRD and included in this study had experienced a component of AKI superimposed on their CKD, which in turn may have influenced the likelihood of recovery of dialysis-independent renal function according to the nature of the underlying kidney disease. The effect of this issue on renal recovery estimates was mitigated by restricting the analysis to patients who remained on dialysis >90 days. It is also possible that patients with severe, acute AAV may have died before being registered with ANZDATA because they had not been deemed to have ESRD. In common with other registries, ANZDATA is a voluntary registry and there is no external audit of data accuracy, including the diagnosis of AAV. Because the diagnosis of AAV and comorbidities was determined by the patient’s attending nephrologist, the possibility of coding bias cannot be excluded.

This study demonstrated that patients with ESRD secondary to MPA or GPA experience dialysis survival outcomes comparable with patients with other forms of ESRD. Although renal transplant graft and patient survival rates were lower in patients with MPA compared with either GPA or other forms of ESRD, 10-year rates were still reasonable (50% and 68%, respectively). Therefore, patients with MPA or GPA should be afforded similar access opportunities to both dialysis and renal transplantation.

Disclosures

S.P.M. has received speaking honoraria from Amgen Australia, Fresenius Australia, and Solvay Pharmaceuticals and travel grants from Amgen Australia, Genzyme Australia, and Janssen-Cilag. N.B. has previously received research funds from Roche, travel grants from Roche, Amgen, and Janssen-Cilag, and speaking honoraria from Roche. F.G.B. is a consultant for Baxter and Fresenius and has received travel grants from Amgen and Roche. D.W.J. is a consultant for Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd and has previously received research funds from this company. He has also received speakers’ honoraria and research grants from Fresenius Medical Care and is a current recipient of a Queensland Government Health Research Fellowship.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the substantial contributions of the entire Australian and New Zealand nephrology community (physicians, surgeons, database managers, nurses, renal operators, and patients) in providing information for and maintaining the ANZDATA Registry database.

W.T. was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project 30900681), the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis Scholarship fellowship program, and the Fund of Peking University Third Hospital (76496-02).

The results presented in this article have not been published elsewhere in whole or part as of acceptance.

Footnotes

W.T. and B.B. contributed equally to this work.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Shen J, Gill J, Shangguan M, Sampaio MS, Bunnapradist S: Outcomes of renal transplantation in recipients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Clin Transplant 25: 380–387, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennette JC, Falk RJ: Small-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med 337: 1512–1523, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross WL, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Hunder GG, Kallenberg CG: Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 37: 187–192, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott DG, Bacon PA, Elliott PJ, Tribe CR, Wallington TB: Systemic vasculitis in a district general hospital 1972-1980: Clinical and laboratory features, classification and prognosis of 80 cases. Q J Med 51: 292–311, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts RA, Lane SE, Bentham G, Scott DG: Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: A ten-year study in the United Kingdom. Arthritis Rheum 43: 414–419, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ormerod AS, Cook MC: Epidemiology of primary systemic vasculitis in the Australian Capital Territory and south-eastern New South Wales. Intern Med J 38: 816–823, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Guerrero J, Rodriguez-Ledo P, Llorca J: The epidemiology of the primary systemic vasculitides in northwest Spain: Implications of the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions. Arthritis Rheum 49: 388–393, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammad AJ, Jacobsson LT, Westman KW, Sturfelt G, Segelmark M: Incidence and survival rates in Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome and polyarteritis nodosa. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48: 1560–1565, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westman KW, Bygren PG, Olsson H, Ranstam J, Wieslander J: Relapse rate, renal survival, and cancer morbidity in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis or microscopic polyangiitis with renal involvement. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 842–852, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walton EW: Giant-cell granuloma of the respiratory tract (Wegener’s granulomatosis). BMJ 2: 265–270, 1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booth AD, Almond MK, Burns A, Ellis P, Gaskin G, Neild GH, Plaisance M, Pusey CD, Jayne DR; Pan-Thames Renal Research Group: Outcome of ANCA-associated renal vasculitis: A 5-year retrospective study. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 776–784, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrassy K, Erb A, Koderisch J, Waldherr R, Ritz E: Wegener’s granulomatosis with renal involvement: Patient survival and correlations between initial renal function, renal histology, therapy and renal outcome. Clin Nephrol 35: 139–147, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nachman PH, Hogan SL, Jennette JC, Falk RJ: Treatment response and relapse in antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated microscopic polyangiitis and glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 33–39, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajema IM, Hagen EC, Hermans J, Noël LH, Waldherr R, Ferrario F, Van Der Woude FJ, Bruijn JA: Kidney biopsy as a predictor for renal outcome in ANCA-associated necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 56: 1751–1758, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aasarod K, Iversen BM, Hammerstrom J, Bostad L, Vatten L, Jorstad S: Wegener's granulomatosis: Clinical course in 108 patients with renal involvement. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 2069, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen A, Pusey C, Gaskin G: Outcome of renal replacement therapy in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated systemic vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1258–1263, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lionaki S, Hogan SL, Jennette CE, Hu Y, Hamra JB, Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Nachman PH: The clinical course of ANCA small-vessel vasculitis on chronic dialysis. Kidney Int 76: 644–651, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nissenson AR, Port FK: Outcome of end-stage renal disease in patients with rare causes of renal failure. III. Systemic/vascular disorders. Q J Med 74: 63–74, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuross S, Davin T, Kjellstrand CM: Wegener’s granulomatosis with severe renal failure: Clinical course and results of dialysis and transplantation. Clin Nephrol 16: 172–180, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews PA, Warr KJ, Hicks JA, Cameron JS: Impaired outcome of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in immunosuppressed patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 1104–1108, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coward RA, Hamdy NAT, Shortland JS, Brown CB: Renal micropolyarteritis: A treatable condition. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1: 31–37, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine JP, Gray, RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB: Tutorial in biostatistics: Competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med 26: 2389–2430, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toussaint N, Caring for Australians with Renal Impairment (CARI) : The CARI guidelines. Renal transplantation. Nephrology (Carlton) 13[Suppl 2]: S37–S43, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]