Abstract

Background

African-American patients are significantly less likely to undergo knee replacement for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Racial difference in preference (willingness) has emerged as a key factor.

Objective

To examine the efficacy of a patient-centered educational intervention on patient willingness and the likelihood of receiving a referral to orthopedics.

Methods

Randomized, controlled, 2×2 factorial design.

Patients

639 black patients with moderate to severe knee osteoarthritis from three Veterans Affairs primary care clinics.

Intervention

Knee osteoarthritis decision aid video with/without brief counseling.

Main Measures

Change in patient willingness and receipt of a referral to orthopedics. Also assessed were whether patients discussed knee pain with their provider or saw orthopedics within 12 months of the intervention.

Results

At baseline, 67% of participants were definitely/probably willing to consider knee replacement with no difference among the groups. The intervention increased patient willingness (75%) in all groups at one month. For those who received the decision aid intervention alone, the gains were sustained for up to 3 months. By 12 months post intervention subjects who received any intervention were more likely to report engaging their provider in a discussion about knee pain (92% vs 85%), have a referral to orthopedics (18% vs 13%) and for those with a referral attend an orthopedic consult (63% vs 50%).

Conclusion

An educational intervention significantly increased African-American patient willingness to consider knee replacement. It also improved the likelihood of patient-provider discussion about knee pain and access to surgical evaluation.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent form of arthritis and is among the most prevalent chronic conditions in the US.1 More specifically, OA of the knee is associated with limitations in physical activity, mobility, and self-care, as well as with loss of earnings and work disability.2 There is no known cure for knee OA. However, when conservative management fails, total knee replacement (TKR) is an effective treatment option for end-stage OA. A systematic review by the Agency for Health Care Quality (AHRQ) of over 129 studies examined the evidence base for TKR and found that3 TKR in the management of OA is one of the fastest growing elective procedures.

Over the past 10-15 years numerous studies have documented marked racial variations in the utilization of TKR.4-11 Most recently, in the winter of 2009, the CDC released a report showing that racial disparity in knee replacement is not only persistent but is potentially widening.12 With the increasing prevalence of knee OA, the number of TKRs is climbing. But this trend is highly variable by race. The rates of TKR among white patients are increasing at twice the rate of African-American (AA) patients.13 Although the reasons for racial variations in the utilization of total joint replacement remain a subject of intense research, recent work shows that racial differences in patient preference (willingness) to be an important factor.14-17 A study of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients found that AAs were less likely than whites to be willing to consider joint replacement.15 More importantly, compared to white patients, AAs in that study considered joint replacement a less helpful treatment option.18 In another study examining willingness to pay for knee replacement among a sample of patients in Houston, TX, AAs were less willing to pay for knee replacement than white participants, even after adjusting for age, income, educational level, and other factors.19 Patient preference is in part an attitudinal disposition whose activation can be subject to the moderating effects of familiarity or knowledge regarding the treatment.20 A pilot study by Weng et al. that used a combination of knee DA and a personalized arthritis report as an intervention found that such intervention improved patient willingness in AAs (P=0.06) but not among white patients.21

The primary objective of this randomized, controlled trial was to investigate the efficacy of a patient-centered educational intervention consisting of decision-aid and/or motivational interviewing on patient willingness, and whether such an intervention would impact referral rates for surgical consideration for AA patients with knee OA. The central hypothesis of this research is that a scientifically accurate, high quality, patient-centered educational intervention delivered using a decisions-aid and supplemented with motivational interviewing to contextualize new knowledge might reshape AA patient’s preference regarding joint replacement as treatment option and improve their access to surgical evaluation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Participants

AA primary care patients greater than age 55 with knee OA defined as chronic, frequent knee pain based on the NHANES questions, WOMAC score ≥ 39, and radiographic evidence of knee OA, were eligible for the study. Potential participants were identified from the VA clinical databases at 3 academic VA medical centers (Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Philadelphia VA medical centers) between March 2007 and February 2009. Patients were screened by research staff using a brief screening questionnaire (The Arthritis Supplement National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I (NHANES I) to identify the presence of chronic, frequent knee pain. Patients were also asked to self-identify their race. Individuals that screened positive for chronic knee pain and who self-identified as African-American were then assessed for the severity of knee OA using the Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities Index (WOMAC).22 Patients with scores ≥39 were considered potential candidates for joint replacement and thus eligible for this study.17 Exclusion criteria were the following: prior history of any major joint replacement, terminal illness (e.g., end-stage cancer), physician-diagnosed inflammatory arthritis (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, connective tissue disease, ankylosing spondylitis or other seronegative spondyloarthropathy, or any crystal-induced arthropathy, such as gout or pseudogout), or contra-indications to joint replacement surgery (e.g., lower extremity paralysis as result of stroke) were excluded from the study.

Description of intervention components

Decision Aid (DA)

This study used the knee OA patient DA developed by the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making as a vehicle to deliver high quality, relevant, and timely information on knee OA and joint replacement. Knee OA DA is a 40-minute videotape. It discusses treatment options including lifestyle changes, medications, injections, complementary therapy, and surgery. The risks, benefits, and known efficacy of each treatment option are outlined. It also covers clinical indications, operative duration, hospital duration, and need for rehabilitative care, physical therapy, recovery time and effort, and cost. Also, the risks of knee replacement surgery, including risk of death, how long a single prosthesis lasts, and consideration of whether to have both knees replaced at the same time or one at a time are discussed.

Motivational Interviewing (MI)

MI is a counseling technique originally developed for the management of patients with behavioral conditions such as smoking addiction,23 where it improves treatment adherence.24-28 For this study, we used MI as mechanism to help patients confront their thoughts about TKR and how to engage their primary care doctors about knee pain. Trained, MI-certified interventionists conducted the face-to-face brief MI counseling session that lasted up to 30 minutes. Participants randomized to receive both DA+MI first viewed the DA videotape in the presence of the interventionist. To ensure MI treatment integrity and quality throughout the study period, a random sample of intervention sessions were audio taped and reviewed. The interventionists were then provided with periodic feedback on their performance. A copy of the MI session script that is used by all interventionist is attached as an appendix.

Attention control (AC)

Subjects randomized to the “attention control” arm received a patient educational booklet about OA published by National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders (NIAMS). This booklet provides brief educational program that summarizes how to live with knee OA but does not specifically mention joint replacement.

Randomization and Masking

Using a 2×2 factorial design, patients at each site were randomized to one of the 4 study arms: Decision Aid (DA) only; Motivational Interviewing (MI) only; combination of DA and MI; and an Attention Control (AC). The factorial design was necessary to evaluate both the independent effects of the DA and the MI intervention components. We used permuted block randomization at the level of the patient. Once eligibility was determined, written consent obtained, and the baseline interview completed, the study coordinator opened a sealed envelope containing a computer generated random assignment. Clinical and study staff and study participants were all blinded to assignment until after the baseline interview. The nature of the intervention meant that participants were not blind to the condition after participation in the intervention.

Outcome Measures & Study Procedure

The primary outcome of interest was changes in patient willingness. We also assessed patient knowledge and expectations regarding TKR as possible mediating factors. Secondary outcomes included whether the patient discussed knee pain with his primary care doctor, received a referral to orthopedics, or saw an orthopedic surgeon within 12 months of the intervention. Participant interviews were completed at baseline and at 1, 3 & 12 months following the intervention or the receipt of the AC booklet. Baseline and 1 month follow-up interviews included knowledge questions that were part of the decision-aid, the willingness rating 29 and the Knee Expectations Scale. Interviews at 3 & 12 months asked about discussion of knee pain with the PCP and included the willingness rating and the Knee Expectations Scale. The willingness rating is a 5-category ordinal response scale from “definitely not willing” to “definitely willing.” The Knee Expectations scale used for this study is the Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Expectations Survey, which assesses patient expectations of surgical outcomes following TKR. 30,31 It is a 19-item scale with good reliability and construct validity.32 Referral to orthopedic clinic, seeing an orthopedic surgeon, and the receipt of TKR were all assessed only at 12 months after the intervention. This was done by telephone survey and validated by chart review. The telephone survey was used to capture referral information for patients who may have received care outside the VA system.

Study covariates

Key study covariates assessed at baseline (pre-intervention) included: clinical, demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational attainment, marital status, living situation, employment status, income) and psychosocial covariates such as trust in physicians. Trust was assessed using an 11-item scale developed by Anderson and Dedrick.33,34; health literacy was assessed using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) scale.35,36. Subjects also completed Arthritis Self-Efficacy37,38; Knowledge regarding knee OA and joint replacement; medical comorbidity using Cumulative Index of Illness (CIIR) the interviewer-administered version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index,39,40 and Quality of life using the SF-12v2.41 A full listing of study covariates is shown in Table 1. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all study sites. There were no adverse events reported to the data safety and monitoring board at any time during the study period. This study was registered as a clinical trial (NCT00324857).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Sample

| AC | (DA) | (MI) | DA + MI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=161 | N=162 | N=158 | N=158 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | Statistic F(3,635)1 | p | ||||

| Age, Mean(SD) | 61.28 (8.29) | 60.70 (9.27) | 61.35 (8.73) | 60.94 (8.31) | 0.19 | 0.90 |

| chi-square2 | p | |||||

| Male, n (%) | 152 (94) | 150 (93) | 148 (94) | 149 (94) | 0.57 | 0.90 |

| Education - Less than high school, n (%) | 41 (25) | 39 (24) | 33 (21) | 41 (26) | 1.35 | 0.72 |

| Employment - Currently working, n (%) | 35 (22) | 32 (20) | 37 (23) | 37 (23) | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Marital Status - Currently married, n (%) | 45 (28) | 70 (43) | 54 (34) | 51 (32) | 8.85 | 0.03 |

| Living Situation - Lives alone, n (%) | 72 (45) | 57 (35) | 77 (46) | 74 (47) | - | 5.13 |

| Household Income <15K, n (%) | 88 (57) | 75 (50) | 65 (44) | 79 (55) | 6.16 | 0.10 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical Covariates | F(3,635)3 | p | ||||

|

| ||||||

| WOMAC, Mean (SD)4 | 59.08 (14.08) | 57.15 (14.56) | 56.36 (14.85) | 56.47 (13.98) | 1.19 | 0.31 |

| Arthritis Self Efficacy: | ||||||

| Pain, Mean(SD)5 | 24.42 (10.08) | 25.93 (9.76) | 25.69 (9.02) | 26.63 (9.58) | 1.46 | 0.23 |

| Function, Mean(SD)6 | 57.41 (16.92) | 60.57 (17.29) | 57.47 (17.99) | 55.93 (17.56) | 2.01 | 0.11 |

| Cumulative Illness Scale7 | 2.83 (2.07) | 2.85 (2.03) | 2.88 (1.90) | 3.09 (2.30) | 0.57 | 0.64 |

| SF-12, Mean(SD) | ||||||

| Physical Component | 32.72 (9.07) | 33.46 (8.76) | 32.56 (9.06) | 33.37 (9.39) | 0.38 | 0.77 |

| Mental Component | 45.33 (13.69) | 46.38 (12.49) | 45.79 (12.12) | 45.69 (12.02) | 0.18 | 0.91 |

| Trust in Physician: Mean(SD)8 | 29.18 (3.34) | 29.01 (3.36) | 29.03 (3.01) | 28.92 (3.92) | 0.16 | 0.92 |

AC= Attention Control; DA= Decision Aid; MI= Motivational Interview; SD= Standard Deviation

F (3,365) statistic based comparisons among the 4 groups with analyses of variance

chi-square2 statistic for categorical variables (df=3)

F statistics in these measures had slight variations in the number of observations, range varied from 613-637 observations.

Range: 0-100;

Range: 5-50;

Range: 9-90;

Range: 0-17;

Range: 11-55

Chi-square tests (3df) were used for categorical variables. There are slight variations in the number of subjects that provided some of the demographic information. The largest number of missing data is in the income variable where 43 subjects did not provide responses.

The video only group differs from each of the other 3 groups

(p=0.03)

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics as well as attitudes and knowledge of knee pain and TKR across the 4 intervention groups were done with chi-square statistics for categorical data and analyses of variance for continuous variables. Comparisons across the groups over time on willingness and knee expectation scales were made with mixed effect regressions for the continuous measures and mixed effect logistic regressions for dichotomous outcomes. Given that the 3 sites included subjects in all 4 conditions site was used as a fixed factor in these analyses. The primary effect of interest for these analyses was the interaction of group by time. This was tested by the change in the log-likelihood statistic of the models with and without the interaction. Initial models were carried out with only group and time considered. These models were then supplemented with the key covariates of age, race, gender, site (Cleveland, Pittsburgh or Philadelphia) and clinical severity (WOMAC) score. The following variables were also considered in models: employment status, marital status, household income, trust of physician, baseline and post intervention knowledge of TKR, educational level, household income, emotional well-being, arthritis-specific cultural beliefs, a medical comorbidity index, and quality of life scores. None of these last group of variables was retained in the multivariable models because none met our cutoff for inclusion in the multivariable models (i.e. having a p-value for inclusionof< 0.15 level). All tests were two-sided.

Results

Study Population & Baseline Characteristics

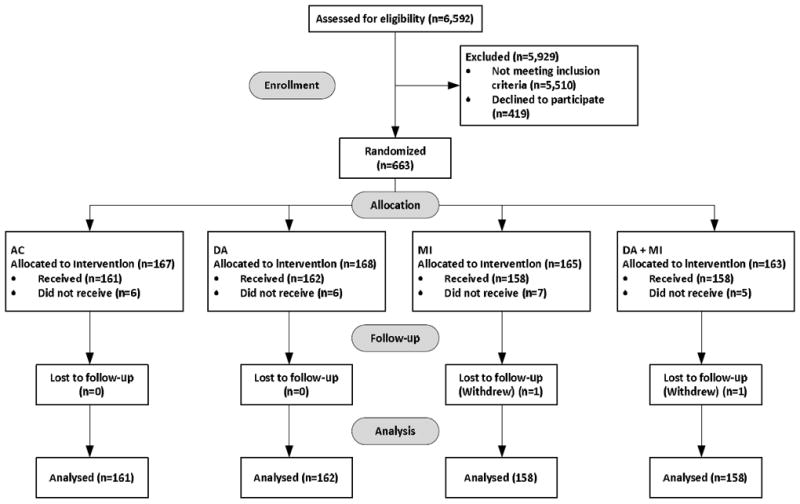

Figure 1 summarizes recruitment and randomization process. 639 participants met the study criteria and were randomized to one of the 4 study arms. There were 24 patients who received the baseline assessment but never received the intervention and were not included in the final analysis. There were no losses to follow-up except for one patient in the MI arm and one patient in DA/MI arm. Over the course of the study 93% of the subjects completed at least 2 of the 3 follow-up interviews with no differences among the 4 intervention groups (p=0.62).

Figure 1.

Schematic Summary of Study Enrollment and Flow

Table 1 summarizes baseline clinical, demographic, and psychosocial characteristics of the sample. There were no statistically significant differences between study arms in the following characteristics: Age, gender, educational level, employment status, living situation, household income, receipt of disability payment, arthritis self-efficacy scores, health literacy level, severity of disease using the WOMAC index, quality of life using the SF-12, trust in physician or index of comorbidity. Study arms at each site were well balanced and the randomization process yielded equivalent distributions of potential clinical, demographic and psychosocial confounders.

Study Outcomes

At one month follow-up, the patients who received the DA either alone or in conjunction with MI demonstrated a significant increase in knowledge items answered correctly (9.5% to 23% answered 3 of the 4 questions correctly in these groups, p<0.05) and there was a borderline increase in knowledge for the group that received only the MI intervention (8% to 15% answered at least 3 of the 4 questions correctly, p=.09). There was no increase in knowledge for the attention control group. Also, knee expectation rating scores did not differ among the groups and the interaction of time and intervention was not significant (chi-square= 1.36, p=0.97).

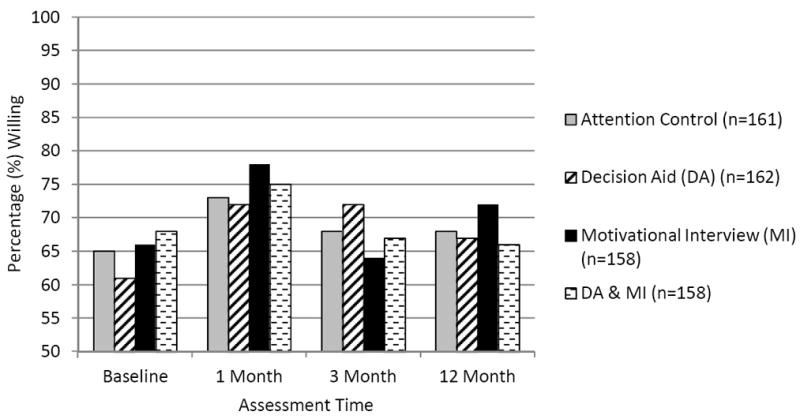

Figure 2 summarizes the observed, unadjusted proportions of patients in each study arm who were willing to consider TKR at baseline and at various post-intervention time periods. At one month post-intervention, all study arms showed increase in patient willingness. Table 2 summarizes adjusted odds ratios from multivariable models for patient willingness, the key study outcome. The reference time period for each of the study arms is the baseline (pre-intervention) for that group. Across all study arms, patient willingness increased from baseline to 1 month (chi-square=21.39, p<0.0001). Odds ratios of increasing willingness at the one month interview ranged from 1.79 (AC) to 2.46 (DA only) but were not significantly different among the groups. Only for the DA group did gains in willingness persist to the three month assessment (OR =2.2, 95% CI 1.16-4.25). Surprisingly, the impact of the combined MI and DA on willingness was not statistically significant at any assessment period.

Figure 2.

Observed Proportions of Patient Willingness Across Groups and Time.

Table 2.

Willingness to consider Total Knee Replacement1

| Assessment | Attention Control | Decision Aid (DA) | Motivational Interview (MI) | DA & MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| AOR2 | 95% CI3 | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Baseline | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 1 Month | 1.79 | 0.98-3.26 | 2.46 | 1.30-4.63 | 2.41 | 1.24-4.69 | 1.97 | 1.00-3.89 |

| 3 Month | 1.16 | 0.63-2.12 | 2.22 | 1.16-4.25 | 0.89 | 0.47-1.68 | 1.01 | 0.52-1.98 |

| 12 month | 1.15 | 0.62-2.13 | 1.96 | 1.00-3.85 | 1.50 | 0.76-2.99 | 0.87 | 0.44-1.72 |

Willingness to have a total knee replacement was dichotomized with definitely and probably willing combined and compared to unsure and not willing combined

AOR= adjusted odds ratio based on models that adjust for age, WOMAC score at screening, and comorbidity index compared to baseline level of willingness. Reported AORs with separate baseline values of willingness for each group.

CI= 95% Confidence Interval of the adjusted odds ratio

category scale: 1) definitely willing, 2) probably willing, 3) unsure, 4) probably not willing, and 5) definitely not willing. Willingness to consider total knee replacement (TKR) was dichotomized, with definitely and probably willing combined and compared to unsure and not willing combined. Values are the adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval). Models were adjusted for age, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index score at screening, and comorbidity index.

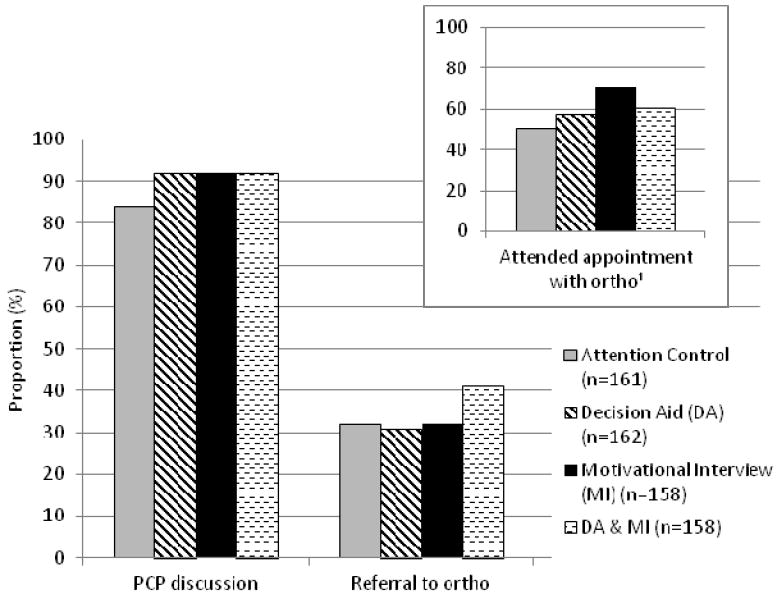

Figure 3 shows proportion of patients who had discussion with primary care provider, referral to orthopedics or appointment with orthopedics at 12 months post-intervention comparing attention control arm to active study arms. Within one year following the intervention 576 (90%) of patient reported having an explicit discussion about knee pain with the primary care doctor. Patients who received the intervention were significantly more likely to discuss knee pain with primary care provider than those in the AC arm (92% vs. 85%, p=0.007) with no difference among the 3 treatment groups(p=0.99) Overall, 16% of patients received a referral to orthopedics. Patient who received any intervention were more likely to be referred (18% versus 13%, p=0.12), however, there were no significant differences among the groups. Of the patients who were referred to orthopedics (n=104), 61% attended their appointment with no differences among the groups (p=0.56).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients who had discussion with provider, referral to orthopedics or appointment with orthopedics at 12 months post intervention comparing attention control arm to active study arms.

1. Only 16% of patients received referral to orthopedics. Among those who were referred, 61 percent received an appointment with ortho.

Ortho= orthopedics. PCP= Primary care provider.

Table 3 summarizes the relationships between intervention and patient likelihood of: a) having a discussion with PCP about knee pain; b) getting referral to an orthopedic specialist; and c) seeing an orthopedic surgeon from multivariable logistic regression models. Again those who received the combined intervention were twice as likely as those in attention control arm to see an orthopedic surgeon. This relationship did not achieve statistical significance in large part because of sample size issue. Only 11 (1.8%) patients reported undergoing knee replacement within 12 months of the study enrollment.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of Discussion with PCP, Referral to orthopedics and Appointment with Orthopedics at 12 months Post Intervention.

| AC | DA | MI | DA & MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratios | Reference Group | AOR1 | 95% CI2 | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Discussion with PCP | 2.39 | 1.14-5.00 | 2.23 | 1.07-4.67 | 2.07 | 1.04-4.26 | |

| Referral to orthopedics | 1.29 | 0.68-2.44 | 1.41 | 0.75-2.65 | 1.85 | 1.00-3.42 | |

| Appointment with orthopedic surgeon3 | 1.27 | 0.54-3.00 | 1.79 | 0.78-4.07 | 2.05 | 0.90-4.65 | |

AC= Attention Control; DA= Decision Aid; MI= Motivational Interview; OR= Odds Ratio; CI= confidence Interval; PCP= primary care provider.

AOR= adjusted odds ratio based on models that adjust for age, WOMAC score at screening, and comorbidity index compared to baseline level of willingness. Reported AORs with separate baseline values of willingness for each group.

CI= 95% Confidence Interval of the adjusted odds ratio

Given a referral to orthopedics

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is one of the first randomized, controlled educational intervention study to address the marked racial variation in the utilization of knee replacement in the management of end-stage knee OA. In a sample of AA patients who were potential candidates for TKR based on clinical criteria, we found that an educational intervention consisting of either DA or MI increased patient willingness at one month. For those who received the DA intervention alone, the gains were sustained for up to 3 months. Patients who received any intervention other than the AC were more likely to report engaging their PCP in a discussion about knee pain and had higher odds of receiving a referral for surgical consideration or seeing an orthopedic surgeon.

The central hypotheses of this educational intervention study was that increasing patient knowledge using a valid, evidence-based knee OA decision aid alone or in combination with brief counseling session using MI technique might help reshape AA patients’ willingness regarding TKR: and that this in turn would lead to focused communication with the primary care provider that might culminate in a referral for surgical consideration. Decision aids are generally used to help patients evaluate critical treatment options that are preference-sensitive. In our study, we used the DA for a slightly different purpose: to deliver high quality, balanced knowledge about the benefits and risk of joint replacement in the management of knee OA. We believe that this goal was in part accomplished as shown by the fact that patient knowledge about treatment options did improve significantly as a result of the DA. Willingness to undergo joint replacement if recommended also improved. However, the effect disappeared before 12 months post-intervention. This could be in part because the intervention needed to be repeated overtime to have a lasting effect. The lack of impact by the intervention on patient expectations was unanticipated. There are several possible explanations to consider: first, it is possible that patient expectations are a function of other factors such as family experience or community perception regarding treatment options for knee OA. The expectation measure we used doesn’t assess all of the possible factors that impact patient expectations. It is also possible that the Knee Expectations Scale might be insensitive to change. The Knee Expectations Scale has not been studied for its responsiveness to change. On the other hand, Weng et al, in pilot study of 54 AA and 48 white patients found that the intervention did not impact patient expectations in white patients, while it achieved barely statistical significance (0.04) only in pain expectations for AA patients 21. Their findings are consistent with our overall findings regarding patient expectations even though we used an entirely different measure of patient expectation. They used pain and function components of the WOMC index to assess patient expectations; while we used the Hospital for Special Surgery Knee expectations survey. Our results are also consistent with the Weng study in showing improvements in willingness among AA patients and patient knowledge.21 That study, which used a combination of knee DA and a personalized arthritis report as an intervention reported improved patient willingness in AAs (P=0.06) but not in white patients. They also found that the intervention increased patient knowledge regarding joint replacement for all patients regardless of race.

We also assessed whether the intervention led to an increase an increase in patient-PCP discussion about knee pain or referral rate for surgical consideration or the likelihood that the patient saw an orthopedic surgeon. Patients who underwent the intervention were more likely to report having had a discussion with the primary care provider about knee OA compared to those who did not receive any intervention. We did not directly assess primary care provider and patient communications to document whether a discussion occurred as reported by the patient and the quality or the nature of such discussion. Patients who received the intervention were also more likely to receive a referral and to see an orthopedic surgeon. However, these relationships did not achieve statistical significance.

We targeted patients in primary care because the path to joint replacement starts with the communication between the primary care provider and the patient. Our assumption was that patients who are less knowledgeable about knee replacement are less likely to bring up orthopedic referral with primary care provider. Therefore, referral for surgical consideration at the primary care level may represent a bottleneck in the path to joint replacement. Our previous findings of racial differences in referral rates to orthopedic surgery,42 also supported the rationale for intervening at the primary care stage. Although the intervention increased referral rate compared to no intervention, overall the cohort showed low referral rate. It is probable that at the primary care level, factors other than patient willingness to consider surgery play a role in the decision to refer. In general, primary care physicians do not objectively assess patient willingness to consider surgery in their routine care of knee OA or in their deliberations about orthopedic referral. Patient willingness is a much more salient issue in the orthopedic doctor-patient communication. For instance, in a previous study we found that patient willingness to be the single most important patient-level predictor of whether or not a patient receives a recommendation for joint replacement from an orthopedic surgery)43. It is also unclear how much of the low referral rate is related to VA primary care practice pattern where there are strict guidelines for referral to subspecialty care. Further, we did not evaluate baseline referral rate. Our primary goal was to examine whether patients who received the intervention where more likely than those who did not were more likely to get a referral within 12 months of the intervention. Lastly, we were surprised by the lack of incremental effect of the DA in combination with the MI intervention. It is not clear why, but one possible explanation is that patients could not handle so much information delivered in both video form and MI in one session.

There are several limitations to consider in interpreting our results. First, we used an educational intervention that has not been previously tested to shape patient willingness regarding knee OA and treatment options. Therefore, other types of patient-centered educational mechanisms may prove more effective in addressing this disparity. Second, we did not directly assess primary care provider and patient communication to investigate how or whether the intervention reshaped doctor-patient communication about knee OA or joint replacement. This would have been helpful in further evaluating the relationship between intervention and referral rate for surgical consideration. Lastly, our study sample reflects the AA male patient population of the VA health care system. Therefore, our findings might not be generalizable to women or patients outside of the VA system.

In summary, in this sample of AA patients with knee OA who are potential candidates for joint replacement, we found that a patient-centered educational intervention consisting of either DA or MI significantly increased patient willingness to consider joint replacement. Patients who received the intervention (DA or MI) were significantly more likely to engage their PCP in a discussion on knee OA or pain and had a higher likelihood of receiving a referral for surgical consideration. This is an important finding in that we now have a low cost, noninvasive, patient-centered intervention that could potentially increase access to orthopedic care for minority patients who are candidates for joint replacement in the management of end-stage knee OA. If confirmed in future large scale studies, this intervention offers a practical approach to eliminate or reduce one of the most marked racial disparities in health care, namely the utilization of knee joint replacement.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service (IIR 05-234-2, PI: Said A. Ibrahim). Dr. Ibrahim was also supported by a K24 Award (1K24AR055259-01) from the National Institutes of Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Appendix

Motivational Interviewing Strategy (Draft)

Introduction (framing the discussion)

Good afternoon/morning. Thank you very much for agreeing to participate in our study. My name is ---------------. I am a research assistant who will be talking with you today for about 20-30 minutes.

You are invited to participate in this study because you have knee arthritis. We would like to discuss treatment options including knee replacement surgery, for which you may or may not have considered. (For those who are in the video+MI arm add: The video provided information about treatment options for knee arthritis and knee joint replacement that we can talk more about if you’d like). I am here to discuss your knee arthritis and treatment options focusing on joint replacement. To start may I ask you few questions?

Tell me more about your knee arthritis?

How does your knee arthritis impact your ability to get around and do things?

How are you coping with the pain from your knee arthritis?

Now, in the past few months or last 2 years, have you spoken to your primary care doctor about joint replacement as a treatment option for your knee arthritis?

YES: Tell me more about that conversation? What happened? How satisfied were you with that discussion?

NO: Do you feel that you are at a point where you are ready to have a conversation with your primary care doctor about joint replacement as a treatment option for your knee arthritis?

Use the readiness/importance/confidence assessment menu:

I am going to ask you a few more questions that will help us to understand how you feel about this issue:

I. Assessment of Readiness, Importance and Confidence

-

Readiness

-

On scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being higher), How ready are you to have a conversation with your primary care doctor about replacement surgery as a treatment option for your knee arthritis?

-

On a scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being higher), how ready are you in considering replacement surgery for your knee arthritis?

-

-

Importance

On a scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being higher), in thinking about replacement surgery for your knee arthritis, how important are the following matters to your decision?

-

Reduction in Pain

-

Improvement in Function (i.e., walking, dancing)

-

Other, Please mention: _________________________________

-

-

Confidence

Again, on a scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being higher), how confident are you that replacement surgery will work for your knee arthritis?

II. Eliciting Barriers, Concerns, and Positive Motivational Statement

A. Readiness:

|

|

|

| B. Importance: |

Reduction in Pain:

|

|

|

Improvement in Function:

|

|

|

Other:

|

III. Summarizing Pros & Cons

| A. Yes Knee Replacement Surgery | B. No Knee Replacement Surgery | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | Cons | Pros | Cons |

| 1. Less pain | 1. Risk of infection | 1. No risk of death or complication | 1. Difficulty walking |

| 2. Walk easier | 2. Risk of death | 2. No time away from loved ones | 2. Risk of weight gain |

| 3. Can participate in activities such as dancing | 3. Time in hospital | 3. No need for rehab | 3. Risk of developing heart disease |

| 4. Improved quality of life | 4. Time in rehab | 4. No cost to me | 4. Worsening pain |

IV. Assess Patient Values and Goals

| A. Tell me five things that are important to you that your knee arthritis prevents you from doing? | ||

| 1. ____________ | 2. ____________ | 3. ____________ |

| 4. ____________ | 5. ____________ | |

| B. Tell me five things you consider important to your life in the next 10-20 years. | ||

| 1. ____________ | 2. ____________ | 3. ____________ |

| 4. ____________ | 5. ____________ | |

V. Providing a Menu of Options

The menu of options should focus on the key variations of what to discuss with the primary care doctor about knee arthritis during the upcoming visit:

Primary option: Knee replacement and referral to orthopedic clinic.

- Secondary options:

- Better control of knee pain

- Physical therapy for knee pain

- Weight loss program

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, Chang RW. Arthritis prevalence and activity limitations in older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:212–221. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<212::AID-ANR28>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, et al. Total knee replacement. evidence report/technology assessment no 86. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003. (prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center, Minneapolis, MN). AHRQ Publication No. 04-E0006-2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escarce JJ, Epstein KR, Colby DC, Schwartz RP. Racial difference in elderly’s use of medical procedures and diagnostic tests. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:948–954. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.7.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron BJ, Barrett J, Katz JN, Liang MH. Total hip arthroplasty: use and select complications in the U.S. Medicare population Am J Public Health. 1996;86:70–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharkness C, Hamburger S, Moore R, Kaczmarek R. Prevalence of artificial hip implants and use of health services by recipients. Public Health Rep. 1993;106:70–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson MG, May DS, Kelly JJ. Racial differences in the use of total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis among older Americans. Ethn Dis. 1994;4:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoagland FT, Oishi CS, Gialamas GG. Extreme variations in racial rates of total hip arthroplasty for primary coxarthrosis: a population-based study in San Francisco. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:107–110. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz BP, Freund DA, Heck DA, et al. Demographic variation in the rate of knee replacement: a multi-year analysis. Health Serv Res. 1996;31:125–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giacomini M. Gender and ethnic differences in hospital based procedure utilization in California. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1217–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escalante A, Espinosa-Morales R, Del Rincon I, Arroyo R, Older S. Recipients of hip replacement for arthritis are less likely to be Hispanic, independent of access to health care and socioeconomic status. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:390–399. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<390::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Racial disparities in total knee replacement among medicare enrollees - United States, 2000-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(6):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha AK, Fisher ES, Epstein AM. Trends in use of major procedures among black and white elderly: is the gap narrowing? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(Suppl 1):230. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Understanding ethnic differences in the utilization of joint replacement for osteoarthritis: the role of patient-level factors. Med Care. 2002;40(1 Suppl):I44–I51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Differences in expectation on outcome mediate African-American/White differences in “willingness” to consider joint replacement. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2429–2435. doi: 10.1002/art.10494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1016–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients’ preferences. Med Care. 2001;39(3):206–216. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Siminoff LA, Kwoh CK. Variation in perceptions of treatment and self-care practices in elderly with osteoarthritis: a comparison between African-American and white patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:340–345. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<340::AID-ART346>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne MM, O’Malley KJ, Suarez-Almazor ME. Ethnic differences in health preferences: analysis using willingness-to-pay. J Rheum. 2004;31:1811–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottati VC, Isbell LM. Effects of mood during exposure to target information on subsequently reported judgments: an on-line model of misattribution and correction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(1):39–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weng HH, Kaplan RM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Development of a decision aid to address racial disparities in utilization of knee replacement surgery. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007 May 15;57:568–575. doi: 10.1002/art.22670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to anti-rheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller W. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioral Psychotherapy. 1983;11:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allsop S, Saunders B, Phillips M, Carr A. A trial of relapse prevention with severely dependent male problem drinkers. Addiction. 1997;92:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senft RA, Peolen MR, Freeborn DK, Hollis JF. Brief intervention in a primary care setting for hazardous drinkers. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:464–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heather N, Rollnick S, Bell A, Richmond R. Effects of brief counseling among heavy drinkers identified on general hospital wards. Drug and Alcohol Review. 1997;15:29–38. doi: 10.1080/09595239600185641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawker GA, Badley EM, Wright JG, Coyte PC. Understanding willingness to consider hip/knee joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9 Suppl):S73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright JG, Young NL. The patient-specific index: asking patients what they want. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:974–983. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Wickiewicz TL, et al. Patients’ expectations of knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83A:1005–1012. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mancuso CA, Ranawat CS, Esdaile JM, Johanson NA, Charlson ME. Indications for total hip and total knee arthroplasties results of orthopaedic surveys. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:34–46. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67:1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao A, Green D, Zaslavsky A, Koplan J, Cleary P. The relationship between method of physician payment and patient trust. JAMA. 1998;280:1708–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Fam Pract. 1993;25:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;35:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandura A. A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall; 1986. Social foundations of thought and action. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopez JPF, Kwoh CK, Ibrahim SA. African-American patients’ reasons for undergoing or refusing elective knee/hip joint replacement surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(Suppl 1):115. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hausmann LR, Mor M, Hanusa BH, et al. The effect of patient race on total joint replacement recommendations and utilization in the orthopedic setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:982–988. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]