Abstract

Imagined futures, once a vital topic of theoretical inquiry within the sociology of culture, have been sidelined in recent decades. Rational choice models cannot explain the seemingly irrational optimism of youth aspirations, pointing to the need to explore other alternatives. This article incorporates insights from pragmatist theory and cognitive sociology to examine the relationship between imagined futures and present actions and experiences in rural Malawi, where future optimism appears particularly unfounded. Drawing from in-depth interviews and archival sources documenting ideological campaigns promoting schooling, the author shows that four elements are understood to jointly produce educational success: ambitious career goals, sustained effort, unflagging optimism, and resistance to temptation. Aspirations should be interpreted not as rational calculations, but instead as assertions of a virtuous identity, claims to be “one who aspires.”

Studies from around the globe have shown disadvantaged youth expressing ambitious educational goals and remaining highly optimistic about their chances of achieving these goals, even when circumstances afford them few realistic opportunities for success (e.g., Little 1978; Saha 1992; Alexander, Entwistle, and Bedinger 1994; Schneider and Stevenson 2000; Rosenbaum 2001; Khattab 2003; Yair, Khattab, and Benavot 2004; Reynolds et al. 2006; Sikora and Saha 2007; Baird, Burge, and Reynolds 2008; Strand and Winston 2008). In recent decades, efforts to explain the persistence of such optimism have been dominated by rational-choice models, which assume that youth strive to choose the goals that will maximize their chances of future success (e.g., Manski 1993, 2004; Breen 1999; Beattie 2002; Lloyd, Leicht, and Sullivan 2008; Morgan 2005; Gabay-Egozi, Shavit, and Yaish 2010). Culturally based approaches to explaining unrealistic optimism have for the most part been sidelined, for both empirical and theoretical reasons. Beginning in the late 1970s, scholars of educational attainment moved from studying goals as key determinants of students’ trajectories to examining instead how opportunities and constraints shape students’ ability to realize their goals (Morgan 2005). And in the late 1980s, cultural theorists shifted their attention from the selection of ends to the availability of means (Swidler 1986; Vaisey 2009). Indeed, a recent essay calls upon sociologists of culture to “reclaim the analysis of the future” (Mische 2009, p. 702).

In this article, I revisit the topic of imagined futures from the perspective of cultural sociology. I advance an alternative approach to studying aspirations and expectations,2 in which I interpret statements about the future as moral claims rather than as rational choices. Why do imagined futures so often run ahead of objective opportunities? And what can such pervasive optimism tell us about how the present is enacted and experienced? I show that aspirations and expectations should be understood as assertions of identity that are shaped by cultural schemas and shared standards of morality. In my interviews with young Malawian women, aspirations emerge as models for self-transformation; individuals fashion their present selves to cohere with an idealized future. I build upon pragmatist theory and cognitive sociology to argue that rather than using what they know about the present to sharpen their view of the future, youth use visions of a brighter future to refine their narratives about themselves and transcend their present reality. By analyzing the cultural model of “bright futures,” espoused by schools, development organizations, government agencies, and media programs, and recapitulated in young women’s own statements, I show that four elements are understood by young women in Malawi to jointly produce educational success: ambitious career goals, sustained effort, unflagging optimism, and resistance to (mostly sexual) temptations. All four components are morality-laden and reflect an individual’s sense of personal identity, the “type of person” that she is at present.

My empirical case is located in rural Malawi, where ideological campaigns surrounding recent schooling reforms have encouraged youth to construct optimistic future projections, despite severe deficiencies in resources and opportunities. While reforms over the past decade have expanded access to primary school, the dream of completing secondary school and continuing on to college remains elusive. According to 2007 statistics provided by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), only 7% of students in their final year of primary school will graduate from secondary school, if current rates remain constant (UNESCO 2007, 2008a, 2008b). Yet, recent survey data show that students are highly optimistic about their own educational trajectories. A longitudinal survey conducted in southern Malawi in 2010 asked 269 female students who had not yet completed their last year of primary school to estimate their chances of finishing secondary school; the average response was 78%.3 Considering that all of these respondents were at least three years behind grade level for their age and most were not yet in their final year of primary school, these women faced even lower probabilities for success than the national estimate of 7%.

To understand how youth imagine their future in Malawi, I draw upon multiple data sources: 40 in-depth interviews with female secondary school students and archival sources, including school curricula, newspaper articles, and printed materials from nongovernmental organizations. Interview respondents report investing exclusively in goals requiring advanced degrees and communicate a high degree of self-efficacy regarding these ambitious goals. If investment in future goals is determined by a conscious calculation of likelihoods and potential benefits, then their responses indeed appear irrational. If, instead, we consider future aspirations as assertions of personal identity, then these strategies become more comprehensible.

THEORIZING IMAGINED FUTURES

Three developments have left imagined futures undertheorized in recent decades. First, scholars studying educational attainment shifted from the Wisconsin model, which posits aspirations as causal mechanisms, to the allocation model, which assumes aspirations to be shared and focuses instead on differences in resources. Second, scholars of culture recoiled from the Parsonian view of culture directly determining the ends of action and focused instead on how culture shapes the means of action. Third, rational-choice scholars have filled the gap that these earlier theorists left behind, advancing a model of aspirations as calculated attempts to maximize future utility based on present circumstances.

I draw upon two sets of intellectual resources to redress the limitations resulting from these developments. First, pragmatist theory allows me to examine imagined futures without resorting to a teleological or instrumental theory of action, to incorporate moral influences on the formation of aspirations, and to deal more realistically with the relationship between ends and means. Second, the concept of cultural models, developed by cognitive sociologists, provides a framework for moving beyond crude models of actors as “cultural dopes” (Garfinkel 1967) while facilitating the examination of how the broader cultural discourse shapes goals and aspirations. At the end of this section, before turning to the empirical case, I specify my use of the terms identity and morality.

From Choice to Allocation in Educational Attainment Research

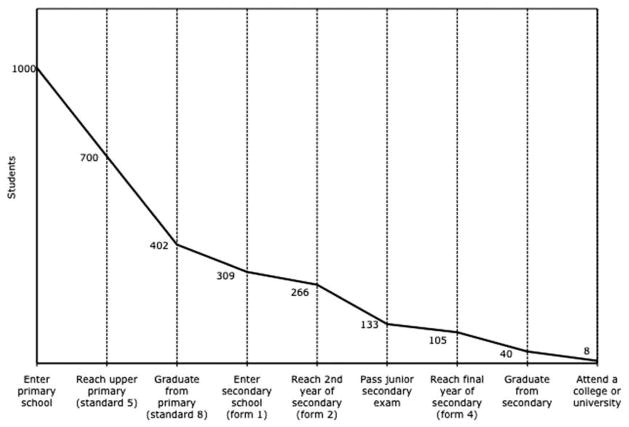

During the 1950s and 1960s, sociologists focused considerable attention on youth aspirations, examining how they are both shaped by social context and play a role in shaping outcomes. Hyman (1953) and Parsons (1953) described differences in future ambitions between lower and upper class youth as key indicators of divergent value systems. Sewell, Haller, and Portes (1969) introduced the Wisconsin model of status attainment (fig. 1), which, as originally specified, assumed that aspirations operated as mediators, transmitting anterior factors of social context (specifically, the influence of parents and peers) into subsequent educational and occupational attainment.4

Fig. 1.

Wisconsin model of status attainment

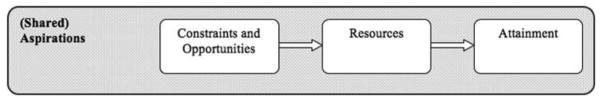

Beginning in the 1970s, new evidence that black and white students with similarly ambitious goals achieved dramatically different levels of educational attainment (Portes and Wilson 1976; Kerckhoff and Campbell 1977) led Kerckhoff (1976) to introduce the allocation model, which instead posits that structural constraints intervene between the choice of an aspiration and eventual educational attainment ( see fig. 2). Because the allocation model stipulates that outcomes are driven by structural factors rather than by the choice of a future goal, this perspective has pushed aspirations and expectations to the background of scholarly inquiry.5

Fig. 2.

Resource allocation model

From Ends to Means in the Sociology of Culture

At around the same time that the allocation model was gaining prominence among scholars of educational attainment, scholars of culture began to distance themselves from the view that values and goals directly determine outcomes. Parsons, Hyman, Sewell, and others had begun with the assumption that aspirations play a causal role in action and focused on culture’s role in motivating behavior. This new wave of research embraced instead the premise that “the very poor share the values and aspirations of the middle class” (Swidler 1986, p. 275) and focused on how culture shapes the means or “skills, styles, habits, and capacities” (Swidler 2001, p. 86) used to realize these commonly held goals (DiMaggio 1997; Lareau 2003; Harding 2007; Lamont and Small 2008). In other words, rather than concentrating on differences in values or ends, this perspective examines how culture shapes the means through which individuals work to achieve their goals.

Scholars have recently criticized this shift in emphasis from ends to means on theoretical, methodological, and empirical grounds (Kaufman 2004; Vaisey 2008, 2009) and advanced an alternative theory of how culture influences action, which emphasizes how culture shapes the ends of action, or the values, goals, and desires that we strive for. I build on the common ground between the two sides of this debate. I find, as Vaisey proposes, that “identities can be thought of—without contradiction—both as motives and as ‘cultural tools’” (Vaisey 2009, p. 1707). Further, contemporary Malawi easily fits Swidler’s theory of “unsettled times,” periods of rapid and wide-ranging societal change during which ideologies can indeed be motivational or provide “blueprints” for action (Swidler 2001, p. 99). In such a context, aspirations both motivate decisions, such as which courses to take in school, and enable particular strategies of action, such as avoiding early marriage. Rather than arguing for the primacy of either ends or means, I instead attempt to remedy a different consequence of the turn from ends to means, namely, the fact that cultural sociologists have “abandoned” and “neglected” what was once a central concept: imagined futures (Mische 2009, p. 702).6 By exploring how culture shapes both the aspirations that young women strive for as well as the pathways that they imagine leading to their desired goal, my examination of imagined futures borrows crucial insights from both sides of the “ends versus means” debate.7

The Ascendance of Rational Choice Theories of Aspirations

While scholars of educational attainment and culture have turned away from imagined futures, rational choice scholars have devoted considerable attention to the subject (e.g., Manski 1993, 2004; Dominitz and Manski 1996; Keane and Wolpin 1997; Breen 1999; Desjardins, Dundar, and Hendel 1999; Eckstein and Wolpin 1999; Cameron and Heckman 2001; Beattie 2002; Leigh and Gill 2004; Lloyd et al. 2008; Gabay-Egozi et al. 2010).8 A fundamental premise of this literature is that adolescents act as “econometricians” (Manski 1993), observing the returns to schooling gained by older peers, estimating their probability of accomplishing various goals, and choosing the investment that, according to these calculations, will maximize future utility.

In recent years, rational choice scholars have begun to incorporate subjective beliefs and heterogeneous strategies into their analyses of future aspirations and expectations (Breen 1999; Beattie 2002; Morgan 2005; Lloyd et al. 2008; Gabay-Egozi et al. 2010; see Breen and Johnsson [2005] for a review). In the most sophisticated elaboration of this approach, Morgan (2005) explicitly sets out to integrate a rational choice model of decision making with insights from the early Wisconsin model—specifically, the idea that educational attainment is contingent on contextual factors shaping subjective beliefs about the future. While this model is promising, measurement of contextual factors remains limited to information communicated by “significant others,” including parents, peers, and teachers, and Morgan himself points to the need for further investigation into this process (2005, p. 213). Further, this model still constrains aspirations to be rational choices, with subjective beliefs and social influence assumed to alter an individual’s process of choosing the goal most likely to maximize utility. The ample evidence that aspirations are often uncorrelated with available opportunities warrants a more radical departure from the rational choice approach.

The Pragmatist Alternative to the Rational Choice Model of Imagined Futures

The American pragmatist tradition, first emerging out of the University of Chicago in the early decades of the 20th century, provides a fertile ground for developing a theoretical alternative to rational choice models of future aspirations, in three respects. First, pragmatists offer an alternative to the rational choice explanation for why the future matters; they theorize the imagined future as a crucial element of both creative action and personal identity. Second, pragmatist theory integrates practical and moral influences on action, positing that standards of morality drive action by shaping models of the self. Third, the pragmatist model of action abandons the Kantian dichotomy between means and ends, allowing goals to be both motivating and enabling and to emerge in the course of action itself.

First, unlike rational choice scholars who view future aspirations as indicative of an individual’s ability to accurately predict future outcomes, pragmatists view imagined futures as a core component of human agency, the first step in actively and creatively responding to a situation (Joas 1997; Emirbayer and Mische 1998). As Dewey writes, “We do not use the present to control the future. We use the foresight of the future to refine and expand present activity” (1922, p. 322). Emirbayer and Mische place projectivity, defined as “the imaginative generation … of possible future trajectories,” as the second element of their “chordal triad” of human agency (1998, p. 971).9 Within pragmatist theory, future projectivities are not only recognized as a crucial element of agency; they are also viewed as a key component of a person’s sense of identity (see the “Defining Identity and Morality” section for a discussion of the term identity). Rather than reflecting a “ruthlessly realistic attitude towards ourselves” in the present, Joas states that our identity is fundamentally oriented toward the future and is more aptly described as a “design of a self to which we aspire” (2001, p. 131).10 Similarly, Dewey wrote of the “whole self,” a unified sense of identity that he described as “always directed beyond itself” into the not-yet-realized future (1934, p. 19).

Second, pragmatist theory transcends the rational choice preeminence of instrumental interests over normative values, assuming instead that actions and desires are shaped by a common sense of the good (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Joas 2001). This rejection of the distinction between purposive and normative motivations is crucial to examining the moral underpinnings of future aspirations. Moral standards, according to pragmatist theory, are also tightly linked to an individual’s sense of personal identity, as “values originate in experiences of self-formation and self-transcendence” (Joas 2001, p. 1).

Third, pragmatists do not differentiate means and ends of action; they conceptualize these terms as “two names for the same reality” (Dewey 1922, p. 36). Means and ends can thus be analyzed as temporal sequences of “ends-in-view,” emerging as ends and turning into means as they lead to the formation of new goals at the horizons of the imagination (Whitford 2002, p. 338; see also Gross 2009). This temporal, rather than analytical, distinction between means and ends allows me to examine how aspirations both motivate new lines of action and enable specific decisions or behaviors, combining the “culture as motivations” and “culture as capacities” perspectives (Swidler 1986, 2001; Vaisey 2008, 2009).

While pragmatism offers a fertile ground for theorizing about future aspirations, empirical applications of these concepts are limited. As Emirbayer and Mische write, “Projectivity needs to be rescued from the subjectivist ghetto and put to use in empirical research as an essential element in understanding processes of social reproduction and change” (1998, p. 991). I agree and here seek to explore how the projectivities of female students in Malawi are connected with their present actions and experiences. I use this empirical case to compare the pragmatist model of imagined futures, which posits that youth use idealized visions of their future selves to ascribe significance and moral stature to their present selves, with the rational choice model, which claims that youth use what they know about the present to select optimal future goals.

The Cognitive Approach to Examining How Culture Shapes Imagined Futures

Pragmatist theory provides a promising alternative to the rational choice model of aspirations. This endeavor also requires a wider and sharper lens for studying how culture shapes imagined futures; previous attempts to conceptualize cultural factors have been largely limited to crude measures of the influence of parents and peers (i.e., Picou and Carter 1976; Sewell and Hauser 1980; Morgan 2005).11 For this purpose, I turn to cognitive sociology, which examines the link between interpersonal structures, including social networks and institutions, and internal mental representations (DiMaggio 1997; Zerubavel 1997; Cerulo 2002; Vaisey 2009). The cognitive approach to cultural meanings is particularly germane to studying future aspirations, which necessarily develop at the nexus of internal mental processes (“What should I be when I grow up?”) and social institutions (such as schools and families). As Holland and Quinn state, “Many of our most common and paramount goals are incorporated into cultural understandings and learned as part of this heritage” (1987, p. 22).12

Cultural models provide an ideal tool for this purpose, as they integrate collective social dynamics and individual cognition into a single conceptual model. First developed by cognitive anthropologists, cultural models bridge two opposing definitions of culture: external artifacts of the world and internal representations in the mind (Shore 1998). Shore describes cultural models as stocks of “shared mental associations [that] constrain attention and guide what is perceived as salient” (1998, p. 46). Based on evidence from cognitive science that the mind uses schemas to simplify and organize perception, the cultural models approach posits that shared experiences and resources durably shape schemas and thereby alter our minds (Holland and Quinn 1987; Strauss and Quinn 1997). In this case, the cultural model of bright futures can be thought of as a “recipe” (Shore 1998, p. 66) or a formula for achieving success.

In theorizing the relationship between institutional-level discourse and individual-level cultural schemas, I also build upon Becker’s concept of culture work, which she defines as “the processes by which individuals and groups interpret and deploy parts of their cultural repertoires in changing environments” (1998, p. 467). Becker shows that within religious congregations, individuals actively draw upon cultural materials provided by church leaders as they interpret the shifting racial composition of their community and formulate solutions to problems related to these changes. I examine how young women deploy the bright-futures cultural model in order to frame and solve problems in their lives, both in terms of their educational plans as well as in other domains, including peer social hierarchies and marriage decisions.

Defining Identity and Morality

Identity is understood here not in the collective sense, as an expression of “groupness” (Turner 1999), but rather in the individual sense, as an expression of “self-understanding” (Brubaker and Cooper 2000).13 Joas defines identity as a “communicative and constructive relationship of a person to himself and to that which does not belong to the self” (2001, p. 160). According to this perspective, identity is a continuously evolving narrative about the self, a “reflexive biography” (Giddens 1991, p. 55) that ascribes meaning to circumstances, experiences, and possibilities and articulates a coherent sense of the kind of person that one is (Taylor 1989; Joas 2001; see also Holstein and Gubrium 1999).

I follow the pragmatist tradition and consider morality as a core component of personal identity (Dewey 1922; Joas 2001; see also Taylor 1989; Hitlin 2003). Two broad definitions of morality currently exist within sociology (Hitlin and Vaisey 2010): first, as the content of standards of conduct and conceptions of “the good life” in a specific social context (Calhoun 1991; Hunter 2000; Smith 2003); second, as the evaluation of whether a certain behavior is right or wrong according to implicit standards of harm or fairness (Schwalbe 1990; Stets and Carter 2006). I use the term morality in the former sense and highlight how the aspirational identities asserted by the women in my study are at their core based on a specific conception of what it means for a young woman in rural Malawi to be virtuous.

In sum, I define identity as an individual’s ongoing narrative account of who she is at present, modeled on the future self that she imagines becoming. I examine the personal process of constructing and communicating this model of selfhood, and focus particular attention on the extent to which these reflexive narratives are shaped by shared conceptions of future potentiality and standards of morality.

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES IN MALAWI: PROMISE VERSUS REALITY

Malawi is an ideal location for sociologists to recommence theorizing about imagined futures for two reasons. First, due to recent educational reforms and the ideological campaigns accompanying them, shared understandings of education are in a period of rapid and active construction and are thus more visible than would otherwise be the case. Second, the gap between aspirations and objective chances is particularly wide in Malawi, bringing the puzzle of unrealistic aspirations into sharper relief. The rational choice framework posits that those who construct unrealistic aspirations lack sufficient information to reasonably estimate probabilities of success; this is particularly hard to swallow in a context where less than 1% of the population attends college (UNESCO 2008b).

In 1992, the Malawian Ministry of Education launched GABLE, or Girls’ Attainment of Basic Literacy in Education, which distributed fee waivers for primary school girls (Mundy 2002). Two years later, during the first few months of multiparty democratic rule, Malawi became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to eliminate primary school fees for all students through the Universal Primary Education (UPE) Initiative (Stasavage 2005). Other countries in the region, including Uganda, Ethiopia, and Tanzania, later followed suit. Following the UPE policy, primary school enrollment exploded from 1.9 million in 1993 to 3.1 million in 1994 (Al-Samarrai and Zaman 2007). GABLE and UPE are also credited with increasing gender parity in primary schools (Kadzamira and Rose 2003). Both policies reflect the fact that Education for All emerged as a key policy goal among the World Bank, the United Nations, and other international nongovernmental organizations during the early 1990s (Chabbott 2003; Mundy 2007). In particular, increasing girls’ access to basic education was touted as a panacea for solving various social problems including HIV/AIDS, persistent poverty, and child health outcomes (Vavrus 2003).

The GABLE and UPE policies were accompanied by widespread ideological campaigns emphasizing the “bright futures” now available to Malawian youth (Hau 1997; Wolf and Kainja 1999). As I show below, the benefits of schooling and the factors leading to educational success have been recurrent themes in newspaper articles, radio shows, and other media for at least the past 15 years. Many of these sources placed particular emphasis on expanding the opportunities available to the girl child (Mundy 2002). Schudson (1989, p. 160) states that the retrievability, or accessibility, of a cultural model increases when the model is institutionalized in public discourse or relates to recent dramatic events. Due to the dramatic nature of the GABLE and UPE reforms, and the rose-colored rhetoric surrounding them, cultural models of educational success are likely to be particularly salient in contemporary Malawi.

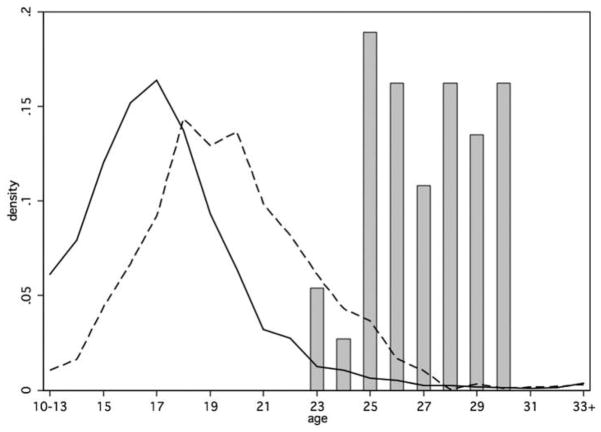

Despite this expansion of the primary school sector, however, attrition remains high in the later grades (fig. 3). According to recent data from UNESCO, if enrollment rates remain constant, out of 1,000 children who entered primary school in 2007, 309 will attend secondary school, 40 will graduate from secondary school, and only 8 will attend postsecondary education (UNESCO 2007, 2008a, 2008b). These figures should be viewed with caution, as school enrollment data are likely to be inaccurate, due to the resource-poor education sector and the absence of widespread computer technology in Malawi. However, the trend that these numbers describe is indisputable: from primary school through to the end of secondary school, Malawian students leave school at alarming rates.14

Fig. 3.

School attrition in Malawi. This figure was created using data provided by UNESCO for 2007, the year before the interviews for this project were conducted (UNESCO 2007, 2008a, 2008b).

The transition from secondary school to college is particularly unpredictable, due to the large number of eligible students vying for a small number of spots (Bloom, Canning, and Chan 2006; World Bank 2010). Malawi currently has the lowest proportion of the population enrolled in higher educational institutions out of 33 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank 2010). In 2007, fewer than 8% of students who entered their final year of secondary school later enrolled in a postsecondary education program, and most of that 8% attended a one-year certificate program rather than a university degree program (UNESCO 2008b). In order to attend college in Malawi, an applicant must score well above average on two tests: the secondary-school-leaving exam and the college entrance exam. Exemplary performance on both exams is necessary but by no means sufficient to secure access to a university education; in 2009, 5,355 students qualified for acceptance to the University of Malawi but only 1,152 were offered admission (University of Malawi 2010). The proportion of applicants meeting the criteria for acceptance who are denied entrance is considerably higher than the 79% suggested by these statistics, as unsuccessful applicants are encouraged to reapply the following year, creating a growing backlog of deserving students waiting at the university gates (World Bank 2010).

The GABLE and UPE policies, as well as the global Education for All initiative, were directed toward a very specific goal: expanding access to primary schooling among the poor. By increasing the number of students at the expense of the quality of education delivered (Chimombo 2005) and through redirecting funds away from the secondary and tertiary sectors (Bloom et al. 2006), the UPE and GABLE programs likely made a college education more distant for the average student, with more students vying for a relatively fixed number of slots. Despite the programmatic emphasis on primary schooling, however, the bright-futures rhetoric surrounding the reforms evokes images of careers such as medicine, banking, and the law, which are accessible only through university training. These ideological campaigns forged a strong link in the popular culture between expanded access to primary schools and later opportunities to attend college and pursue high-skilled careers, resulting in a wide gap between the actual opportunities provided by the educational reforms and the social imaginary surrounding them.

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

Qualitative Interviews

Forty semistructured interviews were conducted with female secondary students in two sites: a district capital in the central region and a trading center in the southern region. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the two regions, differences between the two secondary schools, and summary statistics of the sample. The bulk of the respondents (34) were currently attending the government secondary school in each site.15 To gain the perspective of women with more limited educational opportunities, I also included six respondents who were not currently studying at the government schools but expected to return to school in the next few years: three living in the central site and not attending school at all and three from the southern site attending night-school courses, two hours of instruction given after the normal school day. The southern region of Malawi is considerably poorer, with lower levels of educational attainment at all ages (World Bank 2010). The southern school site is a community day secondary school (CDSS), while the central site is a district-level secondary school (DSS). District-level schools are more selective than community day schools and are of considerably higher quality, with boarding facilities, nicer classrooms, and a larger proportion of certified teachers (UNESCO 2008b).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Interview Sample

| Characteristics | Southern Region | Central Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional: | ||||

| Religion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | Predominantly Muslim | Predominantly Christian | ||

| Language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | Yao, Chichewa | Chichewa | ||

| Marriage system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | Matrilocal, Matrilineal | Patrilocal, Parilineal | ||

| Educational attainment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | Low | Average | ||

| Poverty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | High | Average | ||

|

|

||||

| CDSS | DSS | |||

|

|

||||

| School: | ||||

| Entrance requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | Lower | Higher | ||

| No. of classrooms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 4 | 17 | ||

| No. of teachers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 10 | 35 | ||

| No. of students . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 256 | 680 | ||

| 2007 female graduation rate (%) . . . . . . . | 16 | 40 | ||

|

|

||||

| CDSS | Night School | DSS | Out of School | |

|

|

||||

| Respondent: | ||||

| Age: | ||||

| 16–17 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 11 | 11 | ||

| 18–19 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 3 | 6 | |

| 20+ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| Average . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 17.81 | 18 | 17.5 | 22 |

| Year in school: | ||||

| Form 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Form 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Form 4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 12 | 2 | 14 | |

Note.—For the “Out of School” sample, “Year in school” reflects the grade that the respondent last attended. CDSS = community day secondary school; DSS = district secondary school.

All interviews were conducted in Chichewa, the dominant language in both sites. Three interviewers were selected from a pool of applicants with prior experience in qualitative interviewing. To minimize the effects of the interview setting, I hired young women who were as close as possible to the status of the respondents, residing in nearby towns and possessing no postsecondary credentials. The interview guide was the product of several days of intensive training and discussion between the interviewers and myself. The interviews typically lasted between one and two hours, and most of this time was spent discussing imagined futures.

I was present for six of the interviews; analysis of excerpts coded in NVivo shows no notable differences between these six and those conducted by the interviewers alone.16 We met daily as a team to discuss the interviews, and all interviews were recorded, translated into English, and transcribed soon after they were completed. To ensure consistent translation, five interviews were transcribed by two translators; the transcripts were compared and found to be almost identical in meaning. I reviewed all transcripts with the interviewers at the field site and clarified misunderstandings when necessary. I then read all interviews repeatedly and coded them in NVivo as themes emerged. The quotations chosen here were selected to represent themes present in multiple interviews. To preserve anonymity, each respondent was given a pseudonym from a list of common female Malawian names.

Archival Data

To situate the interview responses within a broader cultural context, I draw from a set of archival records, including nongovernmental organization (NGO) publications given to students to encourage them to attend school (N = 5), “life skills” school curricula (N = 7),17 newspaper articles related to education (N = 43), and secondary sources discussing the ideological campaigns of the GABLE and UPE policies (N = 3). I read every issue of both of Malawi’s daily newspapers, the Nation and the Daily Times, during June and July of 2009, and analyzed all articles having to do with education or offering advice to young people. I also collected all current and previous editions of life skills curricula for secondary school classrooms (seven volumes, totaling 672 pages) as well as NGO manuals disseminated to students during in-school visits (five volumes, 132 pages). To gain a historical perspective, I turned to past editions of the life skills curricula and secondary sources describing the GABLE and UPE ideological campaigns (Wolf 1995; Hau 1997; Wolf and Kainja 1999). Although no combination of sources could provide an exhaustive picture of the ideology to which youth in Malawi have been exposed, the high level of consistency across a number of these diverse sources suggests that they provide an accurate portrayal of national discourse on youth and education.

THE SEEMINGLY IRRATIONAL OPTIMISM OF MALAWIAN SCHOOLGIRLS

In this section, I use interview evidence to show that when viewed through the rational choice framework, the imagined futures of Malawian schoolgirls appear markedly irrational. Despite the immense structural limitations they face, all respondents describe highly ambitious career goals and express a sense of self-efficacy regarding their chances of achieving these goals. These optimistic expectations also lead to trade-offs between education and marriage that appear impractical when examined from the perspective of rational action. While the data presented here provide some insight into shared understandings of educational attainment, the cultural model will be explicitly outlined in the following section.

Ambition and the Role of Agency

All interview respondents imagine their futures in strikingly optimistic terms. Table 2 displays their expected careers; all require years of college-level schooling. There is no notable difference in levels of ambition between students attending the district-level school and those attending the inferior day school, indicating that this disparity in objective opportunities does not lead to variation in imagined futures.18 No age difference was observed: the goals described by older respondents (those who were 18 or older) do not require a significantly different amount of additional schooling.19

TABLE 2.

Career Goals of Students in Interview Sample

| CDSS (1) | DSS (2) | Night School (3) | Out of School (4) | Row Total (5) | Years of Education Required (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 2 |

| Accountant . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 | ||

| Lawyer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Military . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Agricultural or rural development officer . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Banker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Doctor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Journalist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Professor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 2 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Teacher . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Unspecified bachelor’s degree . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| No response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 1 | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Column total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 16 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 40 | |

Note.—Values for years of education required were based on advertisements of certificate programs posted in the newspaper, and the website for the University of Malawi (http://www.unima.mw). For those careers (such as nursing or teaching) for which multiple levels of credentials are available, the lowest level was chosen.

CDSS = community day secondary school; DSS = district secondary school.

These young women also express what appears to be an exaggerated sense of individual agency over their educational trajectories. When asked about potential barriers to achieving their goals, only 11 out of 40 respondents mentioned structural constraints such as lacking money or needing to stay home and help with family responsibilities (see table 3). In contrast, over two-thirds of those who answered this question offered descriptions of personal failures, including succumbing to peer pressure, lacking focus or discipline, and entering sexual relationships.

TABLE 3.

Responses to the Question: What Might Stop You from Achieving Your Goal?

| Personal Failures | Structural Constraints | No Response | Row Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 11 | 4 | 3 | 18 |

| CDSS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 9 | 5 | 2 | 16 |

| Out of school . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Night school . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|

|

||||

| Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 23 | 11 | 6 | 40 |

Note.—Examples of personal failures include being distracted by boyfriends, lack of confidence, insufficient effort, and succumbing to peer pressure. Examples of structural constraints include lack of school fees, death of parent, and inability to study due to family responsibilities.

CDSS = community day secondary school; DSS = district secondary school.

Considering specific responses in more detail yields additional evidence of this pattern. Often, assertions of self-efficacy directly contrast with statements contained in the same interview about severe financial hardship and other objective constraints. For example, when Memory describes her family, it is clear that they are suffering: both of her parents are dead, she lives with her grandmother, and one of her brothers is living in an orphanage because her grandmother is unable to care for all of Memory’s siblings. When describing factors that will determine her likelihood of succeeding, however, she speaks of courage and determination instead of luck or sponsorship.

Interviewer: How much schooling do you ultimately plan to achieve? And tell me why you plan to continue schooling up to this level. And what do you think it will take you to reach this level?

Memory: I want to become a lawyer and I think it will take me a lot of courage to reach where I want, if only I will work hard I think I will make it. I will just have to work hard to achieve what I want, I think.

Interviewer: If something was to stop you from schooling, what do you think it could be?

Memory: Only if I can be doing other bad things like having boy lovers, because I think I can be thinking about him instead of listening to what the teacher is saying and also when studying. (DSS: age 17)

Here, we begin to see a key element of the cultural model of educational success: the link between resisting the temptation of relationships and succeeding in school. According to Memory, if she continues to try her hardest and avoid “boy lovers,” there is no stopping her from her dreams of law school.

Rebecca provides another example of this pattern. She has experienced three deaths in her immediate family (her sister, her mother, and her stepmother), and she often struggles to “find money for all of her needs.” However, when asked what might prevent her from reaching her dream of getting a master’s degree in agriculture, she states:

Rebecca: Sometimes it happens that friends whom you can chat with, they can cause your education to be disturbed. You know, there are other people who have bad behaviors like disobeying the school rules, having sexual relationships; these are some of the things that destroy my future. (CDSS: age 17)

When we remember that less than 8% of students entering their final year of secondary school can expect to enroll in a postsecondary education program (fig. 3), these assertions of self-efficacy regarding scholastic trajectories seem even more implausible, if imagined futures are viewed from the rational choice perspective.

Investment in Education versus Marriage

Interview respondents consistently prioritize educational goals in relation to marriage, even while recognizing the drawbacks of delaying marriage. Marriage in early adulthood remains nearly universal in Malawi, and several respondents describe finding a husband as necessary to becoming a respected adult:

Alice: We Malawians, we believe that a person can be respected only if she has married. Because if you don’t get married, people can still call your first name, unlike a woman who has married—she is respected by being called her husband’s name. (CDSS: age 17)

Rebecca: Women who do not get married they don’t get respect from people compared to those who have married in which they are always respected. That is why I will be married after finishing my education.

Continued investment in schooling is perceived as a potential threat to marriage, limiting women’s marital prospects in two ways. First, committing to long educational trajectories may lead men to judge women as too old when they are finally ready to marry, and second, educated women are perceived as having too high a status relative to men. Evidence from the region suggests that these concerns are real: as women’s levels of education rise relative to men’s, the marriage market can be thrown off balance (Lloyd and Mensch 1999; Quisumbing and Hallman 2005; see also Bourdieu [2008] for an analysis of this phenomenon in rural France). Twenty-eight respondents (70% of the sample) mention this concern; several describe how this topic is discussed in newspapers and is the subject of gossip among friends. The following two excerpts echo common themes surrounding this issue:

Interviewer: Do you know some women in your community who completed their education and struggled to find husbands?

Charity: Yes, there are some of those.

Interviewer: Why did they struggle?

Charity: Because most men are fearing that if they can marry them, maybe they will be abusing their rights like shouting at them.

Interviewer: What else?

Charity: Sometimes men regard these women as older people so they don’t propose to them. (CDSS: age 17)

Interviewer: Okay, have you ever heard of women or to say girls who are struggling to find someone to marry?

Elisa: Yes. Some who are very educated, this can happen.

Interviewer: Can you tell me more about this?

Elisa: I saw it happening, my friend, men don’t ask her out because they say she cannot listen to what they want, and she could have boys saying she cannot say yes to them because they are below her, they just fear her anyway. (DSS: age 22)

Despite widespread recognition that marriage is requisite for successful adulthood in Malawi and that continued education poses a threat to marriage, nearly all of the women in my interview sample speak of delaying marriage for several years in order to pursue their schooling.

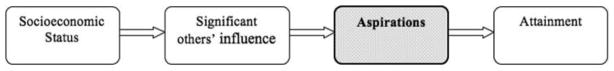

While women with postprimary education tend to marry later than their less educated peers, the vast majority continues to marry in their early 20s. According to the 2004 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), a nationally representative household survey, the median age of first marriage is 18 for all women in Malawi and 21 for women who have reached secondary school or higher (National Statistical Office and ORC Macro 2005). Among the women I interviewed, the average age at which they expect to marry is 27. Figure 4 shows the distribution in desired age at marriage reported by interview respondents compared with data from the 2004 DHS, separated into those who have reached secondary school and those who have not. While it is likely that the age at marriage will increase over the next few years (Mensch, Singh, and Casterline 2005), such an abrupt and dramatic shift in age at marriage is extremely improbable.

Fig. 4.

Expected age at marriage of qualitative sample compared with nationally representative data from the 2004 Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). The DHS estimates use weighted samples ranging in age from 15 to 34.

This passage from the interview with Judith demonstrates the common tendency for interview respondents to relegate marriage to the vague and distant future:

Interviewer: Do you know when you would like to get married?

Judith: No, I don’t, but maybe 28. Because what is happening with me is that I know people who have finished secondary school and then want to marry, but that is not the case with me. I want to go on to college, have my own home first, and start working. I think that is when I will get married but I don’t know when exactly. (DSS: age 17)

For those students who are on track for success in schooling and have the means to pay for further study, such devotion to schooling over marriage might be considered rational. Yet with marriage a near-universal social necessity and the chances of college admission extremely slim, this strategy appears markedly irrational for others. I present two cases for which a rational choice analysis would surely predict a greater level of investment in marriage than is empirically observed.

The first case, Thoko, is 23, and already in the minority as a single woman in her age group. Thoko is not currently in school; she dropped out of form 2 two years before participating in the interview. When asked about her schooling history, Thoko describes her struggles to stay in school despite money shortages and other setbacks:

Thoko: I started at Mzulu Primary from standard 1 to standard 8. Form 1 I attended at [a district level] secondary school, two terms, night classes. Form 2 I started at [this school]. I only learned for a short time, because I did not have enough money. And then I went to [a private secondary school] to start my form 2 classes again…. I learned there but when I wrote my examinations I did not do well…. Since I did not have enough money I could not go back to school. (Out of school: age 23)

Relying on the limited financial support of a brother and an occasional cleaning job, Thoko lacks the resources required to return to school and struggles to feed her family. Achieving her goal of becoming a secondary school teacher appears unlikely: she is 23, is a single mother, and has not yet completed her second year of secondary school. Yet when asked about her expectations for marriage, Thoko replied that she would not consider potential husbands for many years, until she finished school.

Interviewer: Okay, so can you tell me about getting married now? So when do you think you will get married?

Thoko: I need to return to school first, only if I can finish schooling, then I will think of marriage.

Interviewer: How many years do you think will go before getting married?

Thoko: Maybe 5 years or 6 years time.

Interviewer: If a man in two years time is there who you really like, who wants to marry you, what can you do?

Thoko: I would tell him that I want to go to school first because I have suffered a lot. If I finish then we can get married.

For Thoko, scholastic success is highly improbable. Yet in the passage above, she explicitly rejects the idea of investing in marriage and emphasizes instead her commitment to further schooling.

The case of Mary also demonstrates the strength of young women’s exclusive investment in schooling. Mary is 18, in her last year of secondary school, and plans to become a doctor. She is currently in a relationship with a man who is attending college for a degree in accounting. This is quite a catch by the standards of rural Malawi: accounting is one of the most coveted degrees, as it is perceived to more likely lead to stable employment than other university diplomas. Moreover, as Mary describes him, her partner is supportive and caring; she states that he “has never stopped loving me” and “never pressures me at all.” However, when describing this relationship, she emphasizes its minimal impact on her life as a student.

Interviewer: You also told me you have a boyfriend. Can you tell me more?

Mary: Actually when I am here I don’t think of my relationship much. We don’t talk often, and he is not on my mind when I am here.

Interviewer: So aren’t you afraid that some girls might grab him from you?

Mary: If that happens then I will be okay, but now is the time to focus on my schooling. (DSS: age 18)

Mary later makes it clear that she is not factoring this boy into her future plans either. When asked at what age she hopes to get married, Mary replies, “28 or 30 years … because I am sure by then that I will be through with my education and settled.” Indeed, even though she seems to have an unusually promising prospect for marriage, Mary relegates marriage to the distant future.

Misplaced Ambitions, Irrational Investments?

These two cases show that the pattern of exclusive investment in education over marriage extends even to cases where such a strategy would appear to work against the individual’s self-interest. The first is a woman who faces a very low probability of finishing her education and is currently struggling to provide food for her child, who nonetheless intends to delay marriage until a point in the distant future when she will have completed her education. The second is a woman in a relationship with a man who seems, from her description, to be a good candidate for a husband, but who works to keep her relationship on the sidelines in light of her devotion to her educational goals.

These findings are difficult to explain using a rational choice framework. If, as Manski (1993) writes, youth should be thought of as young “econometricians” considering multiple potential future outcomes and investing in the one that they predict will yield the greatest future utility, it seems likely that at least some of the respondents interviewed here would describe intentions to invest in outcomes other than their elusive dreams of high-powered careers. According to this model, youth should base their own chances of success on the experiences of their peers (Manski 1993). Considering that fewer than 10% of form 4 students proceed to universities, students should know that their aspirations are unlikely to be realized. Indeed, nearly all of the interviews reference siblings or friends who failed their exams or were forced to drop out, and many respondents are hard-pressed to think of women who progressed past secondary school. Yet not only do all students profess extremely ambitious educational plans; many also claim efficacy over their futures, which any comparison with the experiences of peers and relatives would quickly disprove. Further, under a model of rational “updating” of preferences, we should expect these unrealistic dreams to break down over time as young women discover the barriers to their success. Yet, no age pattern was evident, and, as Thoko’s story demonstrates, even when a college education is all but impossible, respondents grip their educational aspirations as tightly as ever.

The trade-off between investment in marriage and commitment to education, and the fact that these women view sexual relationships as standing in opposition to schooling, is also difficult to understand from the perspective of Western models of educational success. The idea that one would postpone all romantic relationships until after finishing college would likely sound strange even to the most ambitious American youth. In order to understand the ambitions and investments described above, we must turn to an analysis of their cultural underpinnings.

A CULTURAL MODEL OF EDUCATIONAL SUCCESS

From where do these life plans emerge? To address this question, I now describe the cultural model of bright futures, constructed through a content analysis of the documents described above. I show that the cultural model of bright futures, cultivated by years of government policy, public outreach, and NGO programming, has directly affected the educational plans of interview respondents by shaping a powerful cognitive schema equating commitment to education with achievement of goals. Analysis of these documents yields the following formula, or recipe, for educational success:

In the sections that follow, I outline each of these components, using both archival data and material from the interviews, and then examine the implications of this model for how youth in this context envision and act upon their future goals. I also point to passages where respondents describe discussing the elements of the cultural model with their peers and teachers, demonstrating the extent to which this cultural model is continually renegotiated through social interactions.

Goal Selection: Role Models and the Power of a Career Goal

Youth in Malawi are consistently encouraged to identify specific career goals. These goals ostensibly provide a clear vision of how further education will shape their future lives, arming youth with the determination needed to remain committed to school in the face of challenging circumstances. For example, the first chapter of Youth Alert Magazine, a booklet published by Population Services International and disseminated to secondary school students around the country,20 instructs readers to choose a career goal by completing a series of exercises, from listing their strengths to imagining themselves in 10 years. The Life Skills Curriculum for secondary school students also leads students through a set of activities designed to help them select a future goal. This passage concludes: “If you have clear and specific goals you will be less likely to fall into risky behaviors … because you will be focused and determined to reach your goals” (Malawi Institute of Education 2004, p. 38).

With little formal employment in the villages where most Malawians live, exposing youth to examples of careers is crucial to helping them to select future goals. Indeed, “role models” abound in the Malawian media. A weekly radio show that aired throughout the 1990s, called Tsogolo la Atsikana (Future of women), profiled women working in various fields (Hau 1997, p. 16). In 1996, a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded project promoting the GABLE policy distributed 100,000 copies of a comic book entitled Etta Becomes a Nurse to youth throughout the country (Hau 1997, p. 18). Multiple profiles of role models appear each week in the newspapers, spotlighting journalists, chefs, pilots, and meteorologists (e.g., Mpaso 2009a, 2009b).

In addition to providing models of adults in high-powered careers, the media also profile students who have clearly articulated goals and are working toward fulfilling them. Each issue of the Weekend Nation included at least three such profiles, with the subjects ranging in age from young children to college students. In each case, a picture of a girl is paired with a description of her goals. For example, Ruth Magalanga, a secondary student, writes: “I have an ambition to become a nurse one day and I know education is the only key to open the door into the future” (Mponda 2009). Those who strive, along with those who succeed, are depicted as exemplary.

Interview respondents consistently described their career goals as giving them strength and determination to remain in school. In most cases, the goals listed in table 2 were mentioned spontaneously in response to questions such as “Why do you like school?” or “What do you think is the importance of education?” rather than direct questions about career aspirations. Often, these career goals were also framed in terms of appeals to citizenship; respondents spoke of choosing their goal in order to help others, to contribute to the development of Malawi, and to ease suffering, as in the following interview excerpt:

Interviewer: Do you like school?

Bita: Yes.

Interviewer: Why?

Bita: Because I have a goal; I want to become a nurse.

Interviewer: Why did you choose to become a nurse?

Bita: I want to help other people, I am not happy seeing other people suffering, and I want to help government in increasing the number of nurses. (DSS: age 17)

In explaining the motivations behind their goals, many respondents also mentioned a desire to serve as an example for others in their community. Eritina describes her desire to serve as a “role model for other girls”; Rachel wants “to advise others on the importance of education”; and Bright describes how her family encourages her to go to school, so that she can “be a good example for other people in the village, especially men, who don’t wish to send their girls to school.” These excerpts emphasize the relational aspect of role models and show how cultural models are adapted and shared through social interactions (Shore 1998).

Sustained Effort: “No Sweet without Sweat”

After selecting a goal, students are encouraged to take full responsibility for realizing their chosen career. Several of the documents examined here emphasize that unwavering focus will eventually lead to success. Successful people profiled in the newspapers describe enduring years of adversity until, refusing to give up, they eventually triumph. Mische (2009, p. 701) writes of the need to consider the genre, or the “discursive mode in which future projections are elaborated.” In this case, bright futures are expressed as narrative odysseys, using an oppositional mode of discourse. Those who achieve educational success are described as facing countless obstacles until, at last, through sustained effort, they achieve their goals. Maria Kaitano, a personnel manager at Stockbrokers Malawi, offers the following advice in the Career of the Week newspaper column: “When I look at myself I see achievement. Growing up it was not easy. I like to look back and see what I have done, acquired, or achieved…. Focus on God, hard work, seriousness and discipline have contributed to get me where I am today…. My advice to other women is that no one can take education away from you” (Chikungwa 2009). In another Career of the Week column, a pilot visits a school and encourages students to continue working hard, despite poor conditions and lack of sufficient food. Catherine Magalasi, a student at the school, is quoted as saying, “As a young girl I have learned a lot and I know that there is no limit to what I can do as long as I put all my energy into it. Life now is hard, but if I keep my focus I know I will succeed” (Mpaso 2009b). Meteorologist Elina Kululanga echoes these sentiments: “Life is always challenging and women need to come to terms with this reality and work extra hard. Anything is possible if one has spirit and continues trying” (Mpaso 2009a).

The idea that sustained effort and focus will eventually lead to success was a common theme in the interviews. Liness evokes a phrase printed on a sign by the side of the road, “School for me is about working hard, no sweet without sweat. When I don’t study much, I don’t pass. But if I work hard, in the end I will make it.” This example shows that familiar slogans can enter into cultural models and shape individual cognition. Data from interviews also demonstrate how this element of the cultural model is discussed during social interactions. Several respondents described hearing advice from teachers or older peers about the link between effort and success:

Agnes: I have a certain teacher, she also advises me that no matter how long I will stay without succeeding, if I continue to try my hardest, one day I will find a way to succeed. (DSS: age 17)

Bita: I know a certain woman who is at Mzuzu University, she always inspires me to work hard, she tells me that a lot of people do not work hard at secondary school but they are just killing themselves … so please my dear, take care, life is what you make. (DSS: age 17)

While it is clear that effort in school increases a student’s chance at success, the extent to which this cultural model links persistent effort with certain success is surprising, and helps to contextualize the claims of self-efficacy discussed above. As Holland and Quinn (1987, p. 25) explain, cultural models specify the causal relationships between sets of linked concepts. With phrases like “Anything is possible,” “I know I will succeed,” and “life is what you make,” the bright-futures model establishes sustained effort as a sufficient cause of educational success.

Positive Thinking: “Believe in Your Future”

In addition to sustained effort, bright futures require unflagging positivity. Not only do Malawian students need to endure a long sequence of hardships, they must also never doubt that they will reach their dreams. For example, in the Youth Alert Magazine, music star Ben Michael is quoted as saying, “You must plan for a positive future, stand firm and don’t look back. The road is sometimes rough and rocky but if you are strong and always believe in yourself, you can achieve anything” (p. 17; see note 20). The 2008 Life Skills and Sexual and Reproductive Health Education report contains this story: “Mwandida is a brilliant and well-behaved girl. She is ambitious and wants to become a pilot one day. Last year, her father passed away after a long illness. Two months ago, her mother passed away leaving her with her two sisters and a four year old brother. She is still interested in her schoolwork but her uncle insists that she drop out of school to look after her sisters and brothers. She is very worried, she does not know what to do” (Malawi Institute of Education 2008, 1:69–70). In the activity following the story, students are encouraged to offer suggestions for Mwandida and others like her who face stressful situations. A list of tips is provided on the next page and includes “thinking positively,” “cultivating a positive mental attitude to problems,” “assertiveness,” and “planning for the future” (1:71). The implicit message is that if Mwandida could only keep her positive attitude, her trying circumstances would not get the best of her. A cartoon, also published in the 2008 Life Skills Curriculum, gives another example of the emphasis placed on positive thinking. The cartoon (1:3) reads:

Chikondi: John, I want to pass the examinations and go to college.

John: Impossible! You can’t make it.

Chikondi: I will work hard and pass the examinations.

John: You can’t make it even if you study all the time.

Chikondi: I am confident I will make it…. All I need is the teacher’s encouragement and support to see me through.

John: Okay, we’ll see.

Through repeatedly asserting her confidence, Chikondi convinces her male peer that she is capable of accomplishing her goal.

The need to maintain a positive attitude about the future was also evident in the interviews. Several respondents mentioned the need to maintain a high self-esteem. When asked why so many of her peers have dropped out of school, Rose replies, “I think it is because of lack of confidence. They don’t believe in their future” (DSS: age 16). Describing what might prevent her from becoming an accountant, Chisomo cites “peer pressure.” When questioned further, she says, “My peers usually would like to discourage me from pursuing an accounting course, citing reasons like I am just not good at it and it is better if I make a different choice” (DSS: age 18). Later, when Chisomo is asked about her academic performance, she reveals that she regularly struggles to pass her math exams. It is interesting to note that when questioned about what might potentially keep her from achieving a degree in accounting, Chisomo does not initially bring up her academic troubles, but focuses instead on the discouragement of her peers. It seems that the risk posed by doubt is more potent than that of academic weakness. We can begin to understand Chisomo’s reaction when we recall the definition of cultural models discussed earlier, “shared mental associations [that] constrain attention and guide what is perceived as salient” (Shore 1998, p. 47; cf. Gross 2009, note 7). The cultural model of educational success has filtered Chisomo’s perception of her schooling experiences and shaped which aspects are perceived as threats. Academic performance, a key element of the American model of educational success, is perceived as less salient in this context, when compared to the risk of losing confidence in her potential.

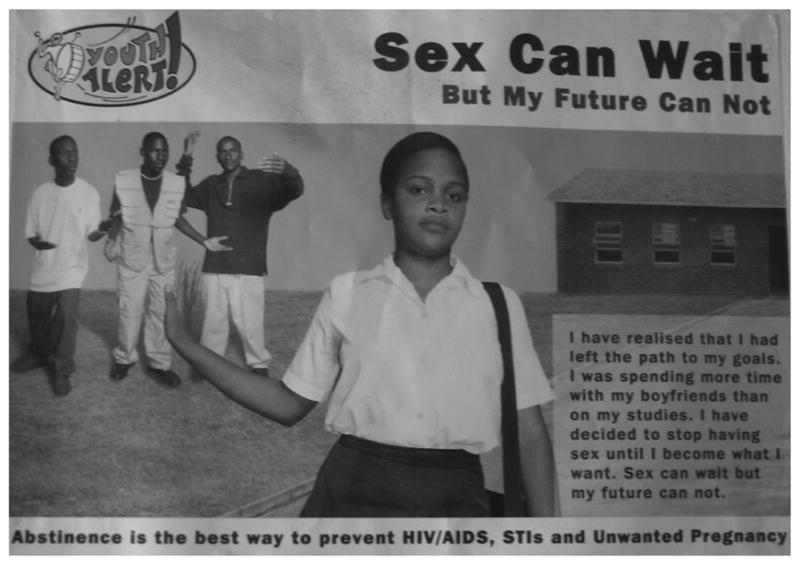

Resistance to Temptation: “Sex Can Wait, but My Future Cannot”

An odyssey, of course, must have its trials. In the documents reviewed here, bright futures are threatened at every turn, as students struggle to withstand the powerful allure of peer pressure, early sex, drugs, and alcohol. Youth are encouraged to draw strength from their future goals in order to resist these temptations. For example, when Youth Alert Magazine introduces the topics of pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and HIV/AIDS, the text repeatedly refers to the goals that students selected in the opening chapter. This passage offers one example: “As you have seen in the previous section, having sex before you are ready can create many barriers to reaching your goals…. These sections will also help you to recognize how dangerous to your bright futures these enemies really are. Think back to when you decided your career goal. Think about the career you put at the end of the bridge, the steps you need to take to reach that career and some of the barriers. If you got pregnant or made a girl pregnant now, what would the extra barriers be?” (p. 63; see note 20).

A poster displayed in the headmaster’s office in the District Secondary School also demonstrates the power of future aspirations to deter youth from taking risks in the present. It shows a schoolgirl with her hand up, saying, “Sex can wait, but my future can not,” to a trio of boys beckoning in the distance (see fig. 5). Youth Alert Magazine includes this statement from a student: “Sometimes I want to be one of the popular girls, but when I think twice about my future I do not take part. Concentrating on my studies is more important than being popular and doing nothing in class” (p. 8; see note 20). These girls are drawing on their future goals to resist peer pressure, a common term in the parlance of youth and, according to the cultural model, one of the most dangerous threats to their bright futures.

Fig. 5.

Poster showing a student inspired by her future goals to resist temptation. Photograph taken by the author in the main office of the DSS in the central region study site.

This risk of being tempted off the path of educational success looms large in the interviews. Respondents often talk of “peer pressure”; this phrase was used, in English, in nine interviews, and other respondents described the risk of “bad companies” and “popular girls.” These influences lead to getting “tied up with simple issues,” such as sexual relationships, beer drinking, not working hard at school, and spending money frivolously. Several respondents describe their commitment to education as giving them the strength to resist these temptations, as this example illustrates:

Bita: Some students do not know how to fight peer pressure. They always wish that they should be like other girls who come from rich families, they select whom to associate with wrongly and that’s what I always think I should not do. My education matters, in remembering this, I think I will achieve what I want. (DSS: age 17)

In these frequent references to the opposition between romantic relationships and educational achievement, we find evidence of how cultural models link schemas together through mental associations: discussions of schooling success often led respondents to mention peer pressure and sexual relationships, showing that these two concepts are connected in respondents’ minds.

Bright Futures: “Education Is Light”

The year 1994 is commonly referred to in Malawi as the country’s “New Dawn” (Posner 1995). After decades of autocratic rule, Bakili Maluzi became president, introducing a new era of multiparty democracy. Symbolism surrounding the “dawning” of democracy abounds: the national flag is a rising sun,21 the currency is the kwacha (Chichewa for dawn) broken into 100 tambala (roosters). The UPE policy, signed in the first few months of Maluzi’s rule, was linked to the new dawn and was said to lead Malawian children to “bright futures.”

The metaphor has persisted: in newspapers, in NGO documents, in school curricula, and in the language of the students themselves, education is consistently discussed in relation to images of light and clarity, while the experiences of the less educated are discussed using language such as “bleak,” “dim,” and “blind.” The Nation, one of the two national newspapers of Malawi, publishes a section every Sunday entitled Education Is Light. Save the Children, an international NGO dedicated to increasing access to education, runs a program instituting Bright Future Committees to encourage dropouts to return to school. In the Life Skills Curricula and Youth Alert Magazine, I found 26 instances of the term “bright futures.”

This image was also evoked in the interviews themselves. For example, Liness declares that “knowledge is light” (DSS: age 16). Mary states, “Riches may evaporate while education brings light that will be with you forever. If you just work hard in school, your bright future will be yours” (DSS: age 18). On the other hand, Margaret explains that “if you don’t have education, you suffer a lot. You live like a blind person who cannot see anything” (out of school: age 24).

The link between futures and light is an example of an image schema, a specific type of mental model that relates virtual concepts, present in the psychological domain, to actual images, present in the physical domain (Holland and Quinn 1987, p. 27). These image-schematic metaphors “have a special status in human thought” and serve as “organizing anchors” for cognition in various realms (Hampe and Grady 2005, p. 45). By relating an abstract concept to a visual image, image-schematic metaphors cause models to become more accessible and easily activated by the brain (Lakoff and Johnson 1980).

WHAT WE LEARN FROM ASPIRATIONAL IDENTITIES

Irrationality Revisited: Aspirational Identities and the Tenacity of Optimism

Above, I presented three ways in which Malawian schoolgirls’ imagined futures appear implausible from a rational choice perspective: (1) they choose strikingly ambitious goals while facing a very low probability of achieving them, (2) they view self-efficacy as sufficient to accomplish these goals, and (3) they relegate marriage to the distant future, even in cases where educational success seems extremely unlikely or they are involved in a promising relationship. After examining the cultural model of educational success, it is time to revisit these findings. When aspirations are viewed from the pragmatist perspective as assertions of present identity rather than as rationally calculated choices among an array of potential futures, these empirical findings become more comprehensible.

We cannot understand why Malawian youth construct such optimistic goals without examining the moral connotations of the cultural model described above (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Joas 2001; Smith 2003). As D’Andrade explains, cultural models that resonate with moral intuitions are highly motivational: “[The] cultural shaping of emotions gives certain cultural representations emotional force, in that individuals experience the truth and rightness of certain ideas as emotions within themselves” (1995, p. 229). In the context of the Education for All initiative and the “universalization” of primary education, the cultural meaning of educational attainment has been dramatically transformed: it no longer speaks to an individual’s inherited social status, but to her moral fortitude (Johnson-Hanks 2006). What is crucial to understand in this context is the extent to which aspirations are also ascribed moral significance. According to the cultural model of bright futures, striving for educational success is understood as choosing the path out of darkness and into the light. Those who have attained a high-status career, as well as those who aspire to do so, are portrayed in the media as role models.

The selection of a future goal is shaped not only by factors related to the outcome, but also by the social meaning of the goal, and what it says about the actor’s place in the world. Independent of the ends to be achieved, the goal itself makes a statement about the person aspiring to it, and the zone of possibility in which she finds herself. The bright-futures rhetoric provides these women with a set of instructions for how to achieve their desired futures, and these instructions all hinge on their ability to sustain belief in their ambitious goals, even in the face of evidence to the contrary. By choosing a career requiring long-term investment, and by continuing to express confidence that they will one day achieve these ambitious goals, schoolgirls in Malawi are asserting to others that they have transcended the boundaries of their present lives and occupy an elite place in society where such long-term foresight is possible.

Keeping this concept of educational aspirations as assertions of identity in mind, let us revisit Bita’s response to the question of why she likes school: “Because I have a goal, I want to become a nurse” (emphasis added). The relationship that Bita draws between enjoying school and having a future goal can now be understood as referring to the fact that by staying in school, Bita can claim the identity of one who aspires. This passage also illuminates how present reality is framed by future projectivities; Bita’s vision of the potential future shapes her current attitude about school (Dewey 1922; Emirbayer and Mische 1998).

According to the cultural model of bright futures, a person’s level of optimism plays a causal role in determining her chances of success in realizing her goals. Thus, in the minds of Malawian youth, success is linked less to intelligence and exemplary academic performance and more to dedication and perseverance. In this context, asserting self-efficacy is not about a realistic calculation of the probability of success, but a means of securing such success. By refusing to give up hope, according to the cultural model, they are moving a little closer to their dreams. If we consider education as an odyssey, then the experience of hardship does not diminish one’s chances of success: it is merely a test of the strength of their will. Recall Thoko, who, when asked whether she would marry someone in the next five years even if she really loved him, replies, “I would tell him that I want to go to school first because I have suffered a lot” (emphasis added). According to the cultural model, Thoko’s faith in her own ability to achieve her dream of being a teacher does not persist in spite of her suffering, but rather it becomes strengthened through hardship.