Abstract

Microparticle release by vascular endothelium has been implicated in various cardiovascular pathologies. Ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) is a life-threatening complication of mechanical ventilation at high tidal volumes associated with excessive mechanical stretch of pulmonary vascular endothelial cells. However, a role of VILI-relevant levels of cyclic stretch in microparticle generation by vascular endothelium remains unknown. We report microparticle formation by human pulmonary endothelial cells exposed to pathologic, but not physiologic, levels of mechanical stress. Stretch-induced microparticle generation was not affected by cell co-treatment with inflammatory agents thrombin or bacterial wall lipopolysacharide. Neither the basal nor the pathologic cyclic stretch-induced microparticle production was affected by Rho kinase and calpain inhibitors, but were instead abolished by caspase inhibitor. In contrast to lipopolysacharide, pathologic mechanical strain did not significantly induce apoptosis in pulmonary endothelial cells. These results show for the first time that mechanical strain of pulmonary endothelial cells at levels relevant to high tidal volume mechanical ventilation is a potent activator of microparticle formation, which requires caspase activity; however, this mechanism is independent of apoptosis. These results suggest a novel mechanism that may contribute to VILI-associated vascular dysfunction.

Keywords: caspase, cyclic stretch, microparticles, pulmonary endothelium

Ventilator induced lung injury (VILI) is a serious condition with high mortality rates and lack of effective therapeutic treatment.[1] VILI is triggered by excessive mechanical stimulation of lung tissue accompanied by endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular leak.[2] Previous studies demonstrated exacerbation of endothelial inflammatory activation and agonist-induced vascular permeability by pathologic mechanical stretch.[2] However, entire pathologic mechanisms induced by high magnitude cyclic stretch (CS) remain to be better characterized.

Microparticles (MP) are membrane fragments shed mainly from cell surfaces of activated, injured, or apoptotic platelets and blood cells and vascular endothelium. Increased levels of circulating MP have been found in blood and vascular pathologies as well as in organ (heart, kidney) dysfunctions.[3–5] Increased MP formation by lung epithelial lining has been recently described in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[5] Increased MP levels serve as a prognostic tool in a number of cardiovascular pathologies,[4] but MP also possess biological activities and may exacerbate existing pathological conditions by promoting inflammatory processes and stimulating intravascular blood coagulation.[6,7] The role of pathologic mechanical stretch in MP release by vascular endothelium remains unknown.

This study tested the hypothesis that excessive mechanical stretch associated with suboptimal mechanical ventilation may stimulate MP formation by lung vascular endothelium. We also examined combined effects of CS and agonist stimulation on MP formation and investigated the mechanisms involved in increased MP production by pathologic magnitudes of CS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

Human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) and cell culture basal medium with growth supplements were obtained from Lonza (Allendale, N.J.). Cells were cultured according to the manufacturer's protocol and used at Passages 5-8. Caspase inhibitor Z-VAD, Rho-kinase inhibitor Y-27632, and calpain protease inhibitor calpeptin were purchased from Bachem Bioscience (Torrance, CA). Unless specified, biochemical reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.).

Cell culture under cyclic stretch and microparticle collection

CS experiments were performed using FX-4000T Flexcell Tension Plus system (Flexcell International, McKeesport, Pa.) as described.[8,9] Experiments were performed in the presence of culture medium containing 2% fetal bovine serum prefiltered through 0.2 μM sterile nylon filters. HPAEC were seeded at standard densities (8 × 105 cells/well) onto collagen I-coated flexible bottom BioFlex plates. Both static HPAEC cultures and cells exposed to CS were seeded onto identical plates to ensure standard culture conditions. After 48 h of culture, each plate was gently washed with the endothelial growth medium (EGM) prefiltered through 0.2-μm sterile filter, and 1.5 ml of EGM medium containing 2% FCS filtered through the 0.2-μm sterile filter was added to each well. Experimental plates with endothelial cell (EC) monolayers were mounted onto Flexcell system and exposed to CS of desired magnitude (5% or 18% elongation) and duration (6-24 hours). Control BioFlex plates with static EC culture were be placed in the same cell culture incubator. When necessary, static controls and CS-exposed HPAEC were treated with thrombin and incubated for 6 h or 24 hours of continuous exposure to both stimuli. At the end of experiment, conditioned media were collected, and centrifuged (2,500 g, 10 minutes, +4C) to sediment cell debris; MP from clarified supernatants were further concentrated by centrifugation (20,000 g, 30 minutes, +4C) and used for fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

Characterization and quantitation of microparticles by FACS analysis

MPs were labeled annexin V coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) in calcium-dependent manner and analyzed by flow cytometry (EPICS XL, Beckman Coulter; Brea, Calif., USA) as previously described.[10] For some experiments, MPs were also labeled with VE-cadherin antibody coupled to phycoerythrin (CD144-PE, Immunotech; Marseille, France) or isotypic control. Events < 1-μm in diameter were identified in forward-scatter and side-scatter intensity dot representation in comparison with fluorescent microbeads (0.5, 0.9, and 3 μm in diameter; Megamix Biocytex; Marseille, France). MPs were defined as elements with a size < 1 μm and > 0.1 μm that were positively labeled with FITC-annexin V or VE-cadherin. Under the present experimental conditions, annexin V labeled over 96% of events in the microparticle gate defined as described above. Presence of apoptotic bodies was assessed as described in[11] by annexin V and propidium iodine labeling of events >1 μ and, therefore, were not included in MP quantification. Levels of apoptotic bodies were at least 50-fold less than the levels of annexin V+ MPs in the different experimental conditions.

TUNNEL assay

Endothelial cells (HPAEC) on 6-well bioflex plates were exposed to static culture (no CS) or pathologic CS (18%) for 24 h ± 100 μM ZVAD or 200 ng/ml lipopolysacharide (LPS). Cells were trypsinized and fixed with 2% PFA for 60 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% triton X for 2 minutes at 4°C. Enzyme terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and fluorescein labeled nucleotide polymers were added for 60 minutes at 37°C. Mean fluorescent intensity was then measured by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three to six independent experiments. Stimulated samples were compared to controls by unpaired Student's t-test. For multiple-group comparison, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post-hoc Tukey test were used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Mechanical strain induces MP formation by human pulmonary artey endothelial cells in an amplitude- and time-dependent manner

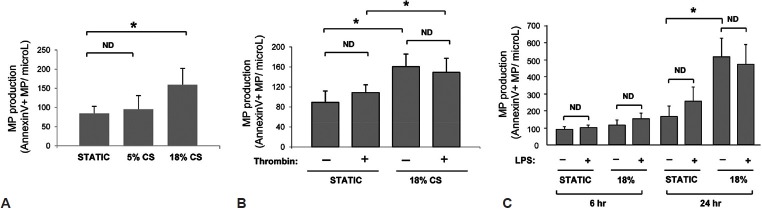

Endothelial cells were cultured at static conditions exposed to 5% CS or 18% CS for up to 24 hours. These amplitudes recapitulate clinical scenarios of mechanical ventilation at low and high tidal volumes.[12] MPs released by static and CS-stimulated HPAEC were quantified as annexin V+ or VE-cadherin+ events. Annexin V+ MP production was significantly increased after 24 hours of 18% CS exposure (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, MP production by HPAEC exposed to 5% CS was not statistically different in comparison to static HPAEC cultures. Similar findings were obtained with VE-cadherin labeling: 18% CS increased VE-cadherin + microparticle production by five-fold (from 14 ± 4 to 82 ± 7 CD144 + EMP/μL; n = 3). E-selectin-positive MPs were below detection levels in these experimental conditions. These findings also confirm previous reports showing that CS does not stimulate E-selectin mRNA expression in cultured endothelial cells.[13]

Figure 1.

Effects of cyclic stretch, thrombin and LPS on microparticle generation by human pulmonary artey endothelial cells. HPAEC were exposed to 6 h (C) or 24 h (A-C) of CS at 5% or 18% elongation. (A) MP formation by HPAEC exposed to 5% and 18% CS. (B) HPAEC were treated with thrombin (0.3 U/ml) 10 min prior to 18% CS exposure. Static cultures were used as controls. *P < 0.05.

Thrombin or lipopolysacharide do not increase microparticles formation in static or CS-preconditioned HPAEC

Synergistic interactions between inflammatory mediators and pathologic mechanical stimulation are essential factors contributing to the two-hit model of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.[14] These conditions were recapitulated in experiments with HPAEC exposed to 18% CS in the presence of inflammatory mediators thrombin or LPS.

Thrombin did not significantly affect MP production by both static and 18% CS-stimulated HPAEC (Fig. 1B). Stimulation of static or 18% CS-exposed cells with LPS during 6 h also did not cause significant activation of MP formation. Pronounced activation of MP production caused by 18% CS was not further affected by HPAEC co-treatment with LPS (Fig. 1C). Similar findings were obtained for VE-cadherin+ MPs. Exposure to LPS did not modify the release of VE-cadherin + MPs either under our basal conditions (control: 14 ± 4; LPS: 14 ± 1 CD144 + MPs/μL; n = 3) or following exposure to 18% CS (18% CS: 82 ± 7; LPS + 18% CS: 68 ± 10 CD144 + MPs/μL; n = 3). Taken altogether, these results show that thrombin and LPS are not potent activators of MP production by HPAEC in comparison to pathologic mechanical stretch.

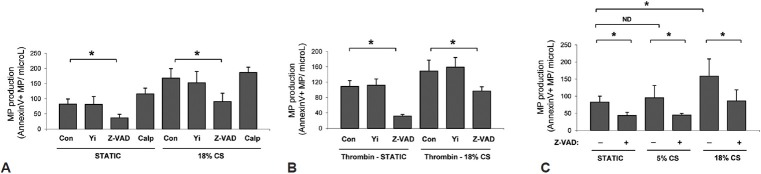

Inhibitory analysis of pathways involved in CS-induced MP production

Several mechanisms mediate MP production by different cell types.[15–17] Pretreatment of HPAEC with Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 or calpain inhibitor calpeptin did not alter CS-induced MP production, but this effect was suppressed by pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (Fig. 2A). Similar inhibitory experiments of Z-VAD-FMK on MP production were observed in HPAEC exposed to 18% CS and thrombin, while Y-27632 was without effect on MP generation (Fig. 2B). Z-VAD-FMK also decreased basal levels of MP production in static cells and in HPAEC exposed to 5% CS (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of CS-induced MP generation. (A) HPAEC pretreated with vehicle, Y-27632 (5 ìM), Z-VAD-FMK (10 μM), or calpeptin (100 μM) were cultured under static conditions or exposed to 18% CS (24 h). (B) HPAEC pretreated with vehicle, Y-27632, or Z-VAD-FMK in the presence of thrombin (0.3 U/ml) were cultured under static conditions or exposed to 18% CS (24 h). (C) HPAEC with or without Z-VAD-FMK pretreatment were exposed to static conditions, 18% CS, or 5% CS (24 h).

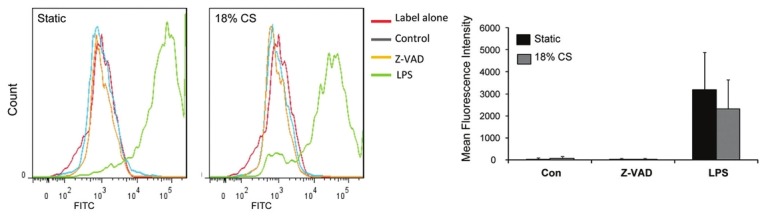

To examine relation between CS-induced MP production and development of apoptosis, we evaluated apoptotic rates in static, LPS-stimulated, and CS-preconditioned HPAEC by TUNNEL assay. Effects of 18% CS on HPAEC apoptosis were negligible in comparison to apoptosis induced by LPS (Fig. 3). Application of pathologic stretch did not further increase LPS-induced apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Effects of 18% CS on HPAEC apoptosis. HPAEC were pretreated for 30 min with Z-VAD-FMK (10 μM) prior to 18% CS or LPS (200 ng/ml) stimulation for 24 h. Apoptosis was evaluated by TUNNEL assay.

DISCUSSION

Microparticles become increasingly recognized as indicators of tissue injury, inflammation, as well as a prognostic tool in certain pathologies. However, direct effects of mechanical stretch associated with ventilator induced lung injury on MP formation by pulmonary endothelium have not been yet explored. This study demonstrates for the first time that pathologic, but not physiologic, CS is a potent activator of MP production by pulmonary endothelium.

Although various potential mechanisms of MP generation have been described, each mechanism appears to be specific to particular cell type or pathogenic stimulus. Activation of intracellular protease calpain led to rapid stimulation of MP production by platelets and involved degradation of actin-binding protein responsible for regulation of cortical actin meshwork.[16] In this study, inhibition of calpain activity did not affect MP production by pulmonary endothelial cells exposed to pathologic CS.

Thrombin-induced activation of RhoA GTPase and Rho kinase was shown to stimulate MP production by microvascular endothelium.[15] Rho signaling is also involved in pathologic responses by pulmonary EC exposed to CS at VILI-relevant amplitude. Rho signaling is further potentiated by combination of pathologic CS and agonist stimulation.[12,18] Interestingly, this study demonstrates that Rho kinase mechanism was not involved in CS-induced MP production by human pulmonary macrovascular endothelium. Furthermore, addition of thrombin to 18% CS-exposed EC at a concentration sufficient to induce permeability response in static culture and enhance endothelial cell barrier disruption and Rho activity under pathologic CS[12] also did not affect the MP production caused by 18% CS. These intriguing differences may be explained by cell type- or model-specific variations and potential interplay of Rho kinase with other signaling pathways involved in thrombin-induced MP production.

In contrast, CS-induced MP production was suppressed by pan-caspase inhibitor ZVAD-FMK. Interestingly, Rho kinase mediated thrombin-induced MP production in microvascular EC, but was also dependent on caspase activity, while in our studies Rho kinase inhibition did not prevent CS-induced MP generation, which was mainly regulated by caspase mechanism. These data suggest that caspase activation may trigger both Rho-dependent and -independent mechanisms of MP production, which may be dictated by cell type and specific pathologic stimulation.

Potent inhibitory effects of ZVAD may suggest apoptotic mechanism of CS-induced MP production. Furthermore, measurable levels of MPs expressing phosphatidylserine and labeling annexin V can be detected under the present experimental conditions and could reflect on endothelial apoptosis.[19] However, previous studies noted modest effects of CS on apoptotic rates,[8,20,21] which are consistent with the results of this study. Interestingly, LPS that caused pronounced endothelial cell apoptosis showed no significant effects on MP production in our model (Fig. 3). These data strongly suggest that caspase-dependent mechanism of CS-induced MP generation by pulmonary endothelium is independent on apoptotic pathway, as it has been reported earlier for thrombin-induced endothelial MP release.[15] Collectively, these data support emerging role of caspase activities in nonapoptotic cellular functions[22] and suggest a novel nonapoptotic function for caspase signaling in CS-induced MP production.

Endothelium-derived MP have been recognized as important signal transmitters, which may act as both pro- and anti-inflammatory stimuli, exhibit prothrombotic activity[23] or be involved in communication between different cell types.[24] We might speculate that MP generated locally by the lung endothelium as result of suboptimal mechanical ventilation may transmit pathological signals distantly and thus contribute to generalized responses to mechanical ventilation known as multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Alternatively, measuring circulating MPs could be a potential biomarker of endothelial injury in VILI. These potentially important mechanisms require further investigation to test these hypotheses.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes grants HL076259, HL058064, FACCTS (University of Chicago), and CODDIM doctoral fellowship for ACV

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA, Esmon C, Bhattacharya J, Coller B, Doerschuk CM, et al. Future research directions in acute lung injury: Summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1027–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-966WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthay MA, Bhattacharya S, Gaver D, Ware LB, Lim LH, Syrkina O, et al. Ventilator-induced lung injury: In vivo and In vitro mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L678–82. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00154.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dignat-George F, Boulanger CM. The many faces of endothelial microparticles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:27–33. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.218123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amabile N, Rautou PE, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microparticles: Key protagonists in cardiovascular disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:907–16. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastarache JA, Fremont RD, Kropski JA, Bossert FR, Ware LB. Procoagulant alveolar microparticles in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1035–41. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00214.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieuwland R, Berckmans RJ, Rotteveel-Eijkman RC, Maquelin KN, Roozendaal KJ, Jansen PG, et al. Cell-derived microparticles generated in patients during cardiopulmonary bypass are highly procoagulant. Circulation. 1997;96:3534–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jude B, Zawadzki C, Susen S, Corseaux D. Relevance of tissue factor in cardiovascular disease. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2005;98:667–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birukov KG, Jacobson JR, Flores AA, Ye SQ, Birukova AA, Verin AD, et al. Magnitude-dependent regulation of pulmonary endothelial cell barrier function by cyclic stretch. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L785–97. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00336.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shikata Y, Rios A, Kawkitinarong K, DePaola N, Garcia JG, Birukov KG. Differential effects of shear stress and cyclic stretch on focal adhesion remodeling, site-specific FAK phosphorylation, and small GTPases in human lung endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304:40–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amabile N, Guérin AP, Leroyer A, Mallat Z, Nguyen C, Boddaert J, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3381–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hristov M, Erl W, Linder S, Weber PC. Apoptotic bodies from endothelial cells enhance the number and initiate the differentiation of human endothelial progenitor cells In vitro. Blood. 2004;104:2761–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birukova AA, Chatchavalvanich S, Rios A, Kawkitinarong K, Garcia JG, Birukov KG. Differential regulation of pulmonary endothelial monolayer integrity by varying degrees of cyclic stretch. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1749–61. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner AH, Hildebrandt A, Baumgarten S, Jungmann A, Müller OJ, Sharov VS, et al. Tyrosine nitration limits stretch-induced CD40 expression and disconnects CD40 signaling in human endothelial cells. Blood. 2011;118:3734–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-320259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank JA, Matthay MA. Science review: Mechanisms of ventilator-induced injury. Crit Care. 2003;7:233–41. doi: 10.1186/cc1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapet C, Simoncini S, Loriod B, Puthier D, Sampol J, Nguyen C, et al. Thrombin-induced endothelial microparticle generation: Identification of a novel pathway involving ROCK-II activation by caspase-2. Blood. 2006;108:1868–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yano Y, Shiba E, Kambayashi J, Sakon M, Kawasaki T, Fujitani K, et al. The effects of calpeptin (a calpain specific inhibitor) on agonist induced microparticle formation from the platelet plasma membrane. Thromb Res. 1993;71:385–96. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90163-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simak J, Holada K, Vostal JG. Release of annexin V-binding membrane microparticles from cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells after treatment with camptothecin. BMC Cell Biol. 2002;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birukova AA, Fu P, Xing J, Yakubov B, Cokic I, Birukov KG. Mechanotransduction by GEF-H1 as a novel mechanism of ventilator-induced vascular endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L837–48. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00263.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez JJ, Jy W, Mauro LM, Soderland C, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Endothelial cells release phenotypically and quantitatively distinct microparticles in activation and apoptosis. Thromb Res. 2003;109:175–80. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raaz U, Kuhn H, Wirtz H, Hammerschmidt S. Rapamycin reduces high-amplitude, mechanical stretch-induced apoptosis in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu XM, Ensenat D, Wang H, Schafer AI, Durante W. Physiologic cyclic stretch inhibits apoptosis in vascular endothelium. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:52–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Algeciras-Schimnich A, Barnhart BC, Peter ME. Apoptosis-independent functions of killer caspases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:721–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morel O, Toti F, Morel N, Freyssinet JM. Microparticles in endothelial cell and vascular homeostasis: Are they really noxious? Haematologica. 2009;94:313–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown GT, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide signaling without a nucleus: Kinase cascades stimulate platelet shedding of proinflammatory IL-1beta-rich microparticles. J Immunol. 2011;186:5489–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]