Abstract

By inhibiting reproductive hormones, the neuropeptide schistosomin produced by the snail Lymnaea stagnalis plays an essential role in parasitic castration mediated by the schistosome parasite Trichobilharzia ocellata during late stage infection. Here we report on the presence and expression of schistosomin in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata, a prominent intermediate host of the parasite Schistosoma mansoni, one of the causative agents of human schistosomiasis. The deduced amino acid (aa) sequences from complementary DNAs (cDNAs) from B. glabrata contain a 17 aa signal peptide and a 79 aa mature peptide with 62–64% identity to schistosomin from L. stagnalis. Ontogenic expression at the protein and mRNA levels showed that schistosomin was in higher abundance in embryos and juveniles relative to mature snails, suggesting that schistosomin is likely involved in developmental processes, not in reproduction. Moreover, expression data demonstrated that infection with two different digenetic trematodes, S. mansoni and Echinostoma paraensei, did not provoke elevated expression of schistosomin in B. glabrata from early stage infection (4 days post exposure; dpe) to patent infection (up to 60 dpe), by which time parasitic castration has been accomplished. In conclusion, our data suggest that a role of schistosomin in parasitic castration cannot be established in B. glabrata infected with either of two trematode species.

Keywords: Schistosomin, Parasitic castration, Biomphalaria glabrata, Schistosoma mansoni, Echinostoma paraensei, Mollusc

1. Introduction

Digenetic trematodes have evolved mechanisms to avoid attacks from their snail host’s internal defenses, but successful infection does not depend on immune interactions alone. These parasites also manipulate the host’s neurophysiology to the benefit of their intramolluscan larval stages [1]. Through modification of host growth and development and by effecting parasitic castration (cessation of reproduction by the host), resources such as space and nutrients otherwise used by the snail host become available for parasite development. Such seemingly diverse feats, manipulation of both host’s immune and neuroendocrine systems, may be facilitated if the two pathways use shared regulatory messengers. Thus for attaining parasite and host compatibility, there might be an important role for host neuro-endocrine factors that regulate both immune and physiological processes and that are susceptible to manipulation by parasites.

An example of such a factor, the snail neuropeptide schistosomin, was identified by study of neuroendocrinological aspects of the association between the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis and the avian schistosome Trichobilharzia ocellata. Intramolluscan stages of T. ocellata stimulate an increase in abundance of this neuropeptide [2, 3], which has been found to be functionally involved in the partial or complete parasitic castration of L. stagnalis 4]. Originally purified from the central nervous system (CNS) of L. stagnalis using biochemical approaches [5, 6], schistosomin originates from telo-glial cells in CNS-associated connective tissue and from hemocytes (circulating defense cells), and was proposed to represent an invertebrate cytokine [7]. While it is thought to be responsible for parasite-induced castration and giant growth of the host [7, 8], the normal physiological role of schistosomin is not yet fully understood. It is also unknown whether schistosomin plays a role in parasitic castration in other snail species.

Far less is known about the neuroendocrinological aspects of parasite-host interactions for the freshwater snail Biomphalaria glabrata, the prominent intermediate host for the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni, one of the causative agents of schistosomiasis. A recent systematic review indicated that more than 200 million people from the developing world are infected and about 800 million individuals are at risk of schistosomiasis [9]. Infection of B. glabrata with S. mansoni results in castration as well [10–12]. Use of an ultracytochemical hormone assay indicated a schistosomin-like activity in hemolymph of several schistosome-infected snail species, including S. mansoni-infected B. glabrata. The authors proposed that schistosomins of different snail species, might be functionally related, yet differ structurally [13]. The lack of sequence information prevented more in depth investigations.

Better understanding of the interplay between B. glabrata and S. mansoni may lead to the development of novel approaches for control of transmission of schistosomiasis. Most efforts to explore the mechanisms underlying snail-parasite compatibility have focused on immune responses of B. glabrata. For example, transcriptomics and proteomics have been applied to identify potential internal defense factors that may be relevant for compatibility [14–18], some of which have been characterized further (for example, [19–26]). Recent gene discovery efforts have yielded expression sequence tags (ESTs) from B. glabrata that encoded predicted amino acid sequences similar to schistosomin from L. stagnalis. Understanding the function of schistosomin and its potential involvement in parasitic castration may help explain why B. glabrata is such a suitable intermediate host for S. mansoni. Using the available information, we characterized the complementary DNA (cDNA) of schistosomin from B. glabrata, generated the recombinant protein, and extensively examined whole snail body mRNA levels and expression of schistosomin protein in the plasma of snails, during ontogeny of B. glabrata and in responses to infection with S. mansoni and another digenean, Echinostoma paraensei.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Organisms used in the study

M line and BS-90 strains of the snail B. glabrata and digenetic trematodes S. mansoni and E. paraensei are routinely maintained in our laboratory [27, 28]. Both trematode species use the snail B. glabrata as an intermediate host for their life cycles. M line and BS-90 snails are susceptible and resistant to S. mansoni, respectively. Three microbes, the gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (wild type), the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli (DH5-alpha strain), and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S288C strain) were from the teaching collection of the Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, USA.

2.2. Experimental exposures, extraction of genomic DNA and RNA

CTAB method [29] was used to extract genomic DNA from a putatively homozygous M line B. glabrata, produced from a parent M line snail after 20 generations of self-fertilization.

To test the ontogenic expression of schistosomin, RNA was extracted from different sizes of M line snails (2–4 mm in shell diameter) (n=100); 7–8mm (n=20), 12–14 mm (n=8), 20–23 mm (n=8)). Snail egg masses (BS-90) which contained 1 to 10 days old embryos were pooled and used for extracting total RNA of the embryos. Three different sizes of BS-90 snails used were 2–5, 8–10, and 13–16 mm, respectively.

To test the expression of schistosomin in response to infection with S. mansoni or E. paraensei, 8–10 juveniles of M line (6–9 mm) at different days post exposure (dpe) to trematode miracidia, as well as unexposed control snails, were used for RNA extraction. The number of miracidia used to infect snails was 10–20 for S. mansoni and about 20 for E. paraensei. In the case of E. paraensei, infection was confirmed microscopically by the presence of sporocysts in the hearts of exposed snails. In the case of S. mansoni infection, all snails at 4 and 15 dpe to S. mansoni miracidia were used without confirmation of infection because it is difficult to identify successful infection during the early stages of schistosome infection. At late stage schistosome infections (30, 45 and 60 dpe), infected snails were identified by cercarial shedding at these time points.

To test the effect of microbial challenge on the expression of Schistosomin, BS-90 snails (6–9 mm) was injected with 5 µl of suspensions, which contains one type of microbes (e.g., S. aureus, or E. coli, or S. cerevisiae), or sham injection consisted of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), according to procedures described previously [30]. The approximate number of colony forming units for S. aureus, E. coli and S. cerevisiae injected per snail was estimated to be 3–4×106, 2–9×106 and 2–5×104, respectively. At 6, and 12 hour (h) post-injection, RNA was extracted from 10 snails for each injection.

Hemolymph was collected from individual snails as described [31]. Plasma and hemocytes were separated by centrifugation at 5 min×1,000 g. Plasma samples were stored at −70 °C for Western blotting. For RNA extraction, whole body tissues of pooled snails including hemocytes were homogenized under liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted by sequential use of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Clontech). In order to obtain high quality of RNA from egg masses, TRIzol method was applied twice followed by use of the NucleoSpin RNA II kit.

2.3. Generation of full-length complementary DNAs (cDNAs)

Schistosomin sequences were PCR amplified from a ë-ZAP cDNA library that had been generated from M line snails that had been infected for 4 days with E. paraensei 32]. The gene-specific primers, forward primer DW474143F (5’-AGTCTACAAGTCCAGCCT-3’) and reverse primer DW474143R2 (5’-CAAATACACGGCACAAGAGT-3’), were designed based on an M line B. glabrata-derived EST sequence (GenBank accession number: DW474143). The 5’ and 3’ cDNA sequences were generated using gene-specific primers and vector primers.

For sequencing, amplicons were cloned into the pCR 2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced on both strands using vector primers. The profile for the sequencing reactions (BigDye, v 1.1, Applied Biosystems (ABI)) was as follow: 95 °C for 17 sec, 50 °C for 12 sec, 60 °C for 4 min, for a total of 29 cycles. The extension products resulting from cycle sequencing were analyzed on an ABI 3130 sequencer.

2.4. Sequence analyses

Alignment of nucleotide (nt) sequences and generation of contiguous sequences were performed using Sequencer (version 4.2; Gene Codes Corporation). BLAST searches were performed using the NCBI Blast program (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast). The signal peptide (SP) and conserved domains were predicted by the SMART program (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de; [33]).

Amino acid (aa) identity was determined using Blast 2 sequences (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bl2seq/wblast2.cgi). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA (version 3) [34].

2.5. Construction of expression vector

Full-length cDNA of schistosomin from M line snails was cloned in pCR2.1 vector Invitrogen). Two primers were used for generation of an expression insert which included entire mature schistosomin (without the SP); forward primer pET23bSchistF (5’ CTACATATGGACAACTACAGGTGCCCCAAC-3’) and reverse primer pET23bSchistR (5’ GTGCTCGAGCATGACAGAGGGGACATCACTG-3’). The corresponding restriction enzyme sites are underlined. The expression vector was constructed using pET23b(+) Novagen).

The resultant construct contained a conventional six-histidine (6xHis) sequence at the C-terminus. The expression vector was transformed into the Escherichia coli Rosetta(DE3)pLysS strain (Novagen). The expression and purification of schistosomin were performed as described previously [31]. Purified recombinant protein was sent to Zymed Laboratories LLC (California, USA) for generation of antiserum in a rabbit.

2.6. Southern and Northern blotting

A oligonucleotide probe (408 bp) covering the entire coding sequence was amplified from the cDNA of schistosomin using forward primer DW474143F1 and reverse primer DW474143R2 described above (section 2.3). The probe sequence was radio-labeled with α-32P dATP (Strip-EZ™, Ambion). Modified versions of the SouthernMax™ and NorthernMax™ methods (Ambion) were applied to conduct Southern blot analyses with this same probe (for details, see [35]). A genomic DNA sample was digested with three different restriction enzymes, Pst I, Hind III and EcoR I. For Northern blotting, an equal amount of RNA (20 or 25 µg) from different experimental snail samples was loaded into each lane.

After separation by electrophoresis, RNA or denatured DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized with the schistosomin probe (the same probe used for Southern blotting) at 42 °C, overnight. The membrane was washed to high stringency according to supplier’s instructions (Ambion).

2.7. Western blotting

Protein content of all plasma samples was measured using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo). An equal amount of total plasma protein (normally 1–3 µl, depending on concentration of protein in the plasma samples) was diluted 10-fold in Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad) and loaded into each lane of gradient SDS-PAGE gel (10–20%; BioRad). All SDS-PAGE gels were run under reducing condition (5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol in the sample buffer). The anti-schistosomin serum (at 1/1,000 dilution) was incubated with the blot 2 hrs at room temperature. Immuno-blotting was performed as described [31].

2.8. Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

To validate Northern blot analyses, the same RNA sample used for Northern blotting were used for qPCR analysis. The qPCR primers were forward primer schist-RNAiF (5’-GGCCTCAACTGAATGTACTTCTGA-3’) and reverse primer schist-RNAiR (5’-AGCGATGCCGTTGTGTGA-3’). qPCR was performed on a Sequence Detection System 7000 (ABI) using a SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents kit (ABI), as described previously [30].

Relative gene expression data were obtained using the ΔΔCt method [36], with 18S rDNA as the internal standard. For each sample tested, qPCR was performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was not performed because data were collected as technical replicates, rather than different biological samples. The data are shown as the average value relative to those of the control snails.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of B. glabrata schistosomin-encoding sequences

An ongoing gene discovery project yielded a schistosomin-like single-pass EST sequence from untreated M line B. glabrata (GenBank accession number (GAN): DW474134). A full-length coding sequence was PCR amplified from a cDNA library representing mRNA from E. paraensei-infected M line B. glabrata, and sequenced on both strands (GAN: EU126802). The nucleotide probe for Southern and Northern analyses and the expression construct of recombinant protein described below was generated from this cDNA clone. Two additional single pass schistosomin-like ESTs, derived from BBO2 strain B. glabrata 37] by the WashU Snail EST Project (Washington University Genome Sequencing Center, St Louis, Missouri) were deposited in GenBank (GAN: ES488206, ES485584) (Fig. 1). All four sequences incorporated a complete protein coding region for the small schistosomin sequences, composed of a 17 aa signal peptide (SP) region and a 79 aa mature peptide (Fig. 2A). The four sequences each differ some at the nt level. They encode for two different peptide sequences; they differ at two aa positions, one in the SP region and the other located in the mature peptide region (Fig. 1, 2A).

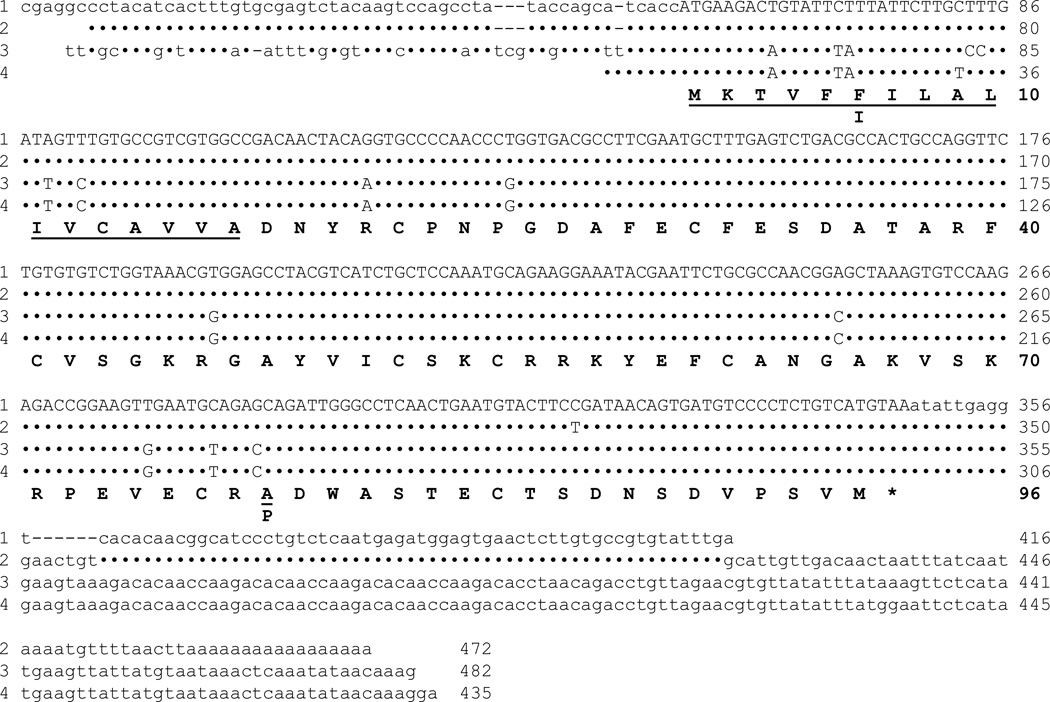

Fig. 1.

Alignment of schistosomin cDNAs identified from B. glabrata and deduced amino acid (aa) sequences. GenBank accession numbers for sequences 1, 2, 3 and 4 are EU126802, DW474143, ES488206, and ES485584, respectively. Numbers in the right margin indicate the positions of nucleotides or amino acids (bold). Signal peptide (SP) is underlined.

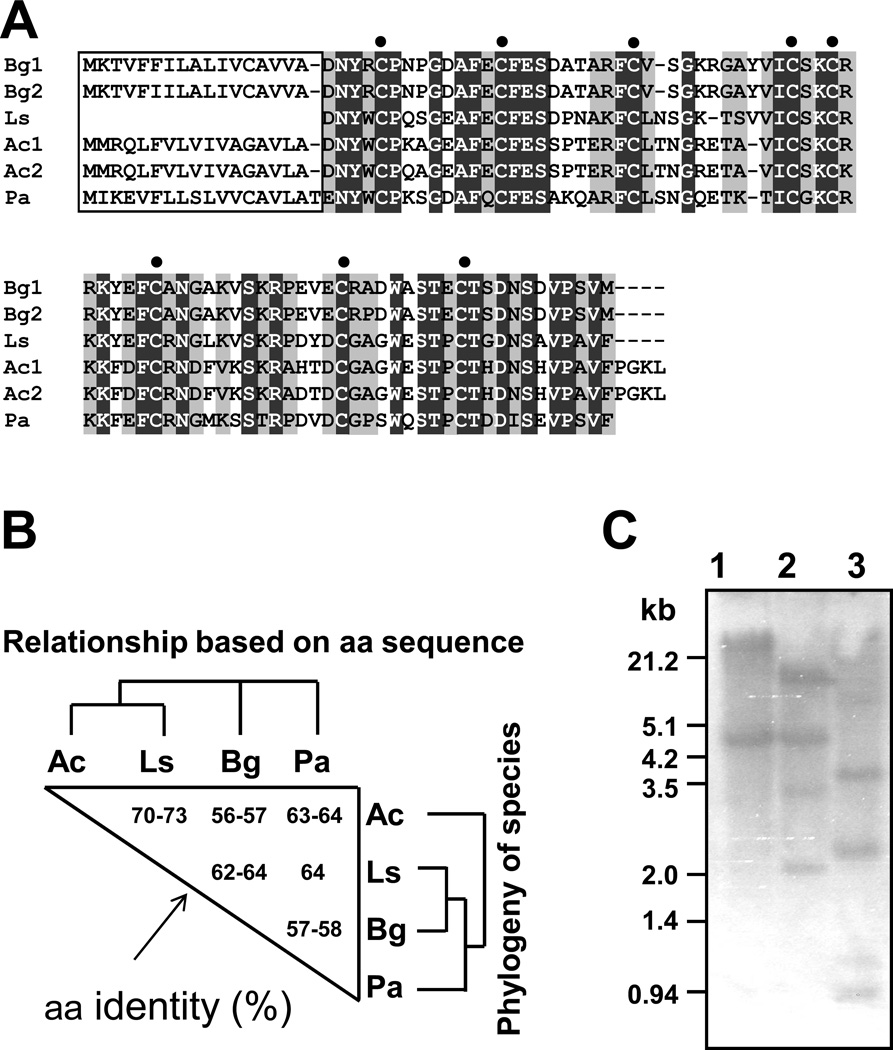

Fig. 2.

Alignment of deduced aa sequences of schistosomin from four molluscan species. (A) Alignment of schistosomins obtained from B. glabrata (Bg) (Bg1: EU126802; Bg2: DW474143), L. stagnalis (Ls) (AAB20290), A. california (Ac) (Ac1: AY833132; Ac2: EB294290), and P. acuta (Pa) (BW986160). The signal peptides (SP) are boxed. Dark and light gray shading areas show regions of sequence with 100% identity and more than 2/3 identity, respectively. The filled circles indicate the eight conserved cysteine residues. (B) Comparison of the schistosomin mature aa sequences. The aa identities (%) are shown in the triangle. Alignment of schistosomin aa sequences was based on aligned residues from the 79-aa mature homologous protein sequences (from 18 to 96 aa in B. glabrata schistosomins). The phylogeny of species involved was based on [39, 40]. (C) Southern blot analyses of schistosomin genes in B. glabrata. Three restriction enzymes, Pst I (lane 1), Hind III (lane 2) and EcoR I (lane 3) were used to digest genomic DNA. Size markers in kilobases (kb) are indicated on the left.

The two B. glabrata-derived aa sequences showed significant aa similarities with the schistosomin sequences reported from three other molluscs, L. stagnalis, Aplysia californica, and Physa acuta (Fig. 2A). The schistosomin sequence from L. stagnalis (GAN: P24471) was determined from a mature 79 aa polypeptide that was purified from the hemolymph; the SP and the nt sequences are unknown. Schistosomin sequences from A. californica and P. acuta were EST sequences deposited in GenBank, and further molecular and functional characterizations were not reported. Schistosomin cDNA sequences from all three species indicated that they all possess a SP, agreeing with the observation that schistosomin is a secreted protein in L. stagnalis. All schistosomins possess eight cysteine residues, believed to form a total of four disulphide bonds [6]. The mature peptide in B. glabrata, L. stagnalis and P. acuta each consists of 79 aa whereas the schistosomins from A. california have 83 aa, with 4 additional aa at the N-terminal region (Fig. 2A).

Extensive NCBI Blast searches did not reveal significant identity of molluscan schistosomins to other known protein domain or sequences. Schistosomin aa mature sequences of A. california and L. stagnalis are most closely related to the sequence from B. glabrata or P. acuta. This aa relationship does not reflect the species phylogeny (Fig. 2B).

Southern analysis of genomic DNA from B. glabrata digested with three different restriction enzymes showed 2 and 4 bands hybridizing with the probe (408 bp) that incorporated the coding region of schistosomin (Fig. 2C). This indicates that the genome of B. glabrata has 2–4 schistosomin loci.

3.2. Expression and purification of recombinant schistosomin proteins in E. coli

A recombinant schistosomin protein consisting of an entire mature peptide was expressed in E. coli and used to generate an antiserum. Figure 3A shows that schistosomin was highly expressed in the bacteria, but formed as an inclusion body. The predicted weight of the amino acid backbone of the recombinant protein is ~10 kDa. We observed a band of 12–14 kDa on SDS-PAGE gels, and this band became a prominent component of the bacterial lysate after induction by IPTG (isopropyl-β-1-D-thiogalactopyranoside) (Fig. 3A). His-tag purification yielded a major band of this size, suggesting that the 12–14 kDa band contains the recombinant schistosomin protein. The difference between the predicted (~10 kDa) and actual size (12–14 kDa) of the protein may result from aggregation, unsuitable electrophoretic conditions or asymmetric structure, phenomena commonly described in many studies (for example, [38]).

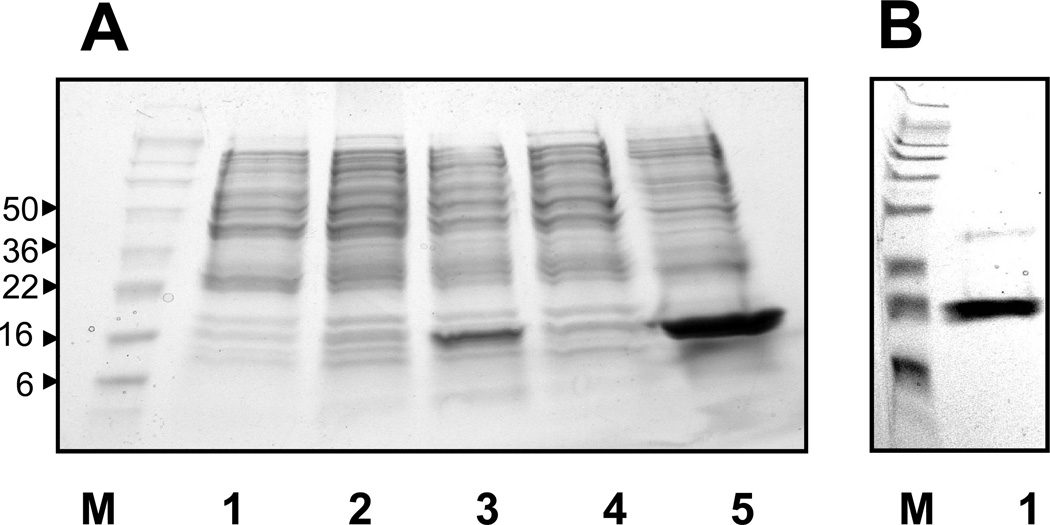

Fig. 3.

SDS-PAGE gels showing the expression in E. coli and purification of recombinant schistosomin. M: molecular weight (kDa). (A) Lanes are 1) the bacterial lysate without transformation of the recombinant vector, 2) transformed with the vector without addition of IPTG, and 3) the transformed bacteria induced by IPTG, respectively. Lanes 4 and 5 show the protein samples collected from supernatant and pellets, respectively. (B) Lane 1 shows the recombinant schistosomin proteins after purification.

The antiserum raised against the recombinant protein specifically detected a strong band of ~14–16 kDa in the plasma samples from B. glabrata, as shown in all Western blots presented in this study. In addition, a ~70–72 kDa band was detected (not shown). Possibly, this represents a cross-reactive snail protein that shares epitopes with schistosomin. However, it is easy to distinguish this protein from schistosomin due to the considerable difference in size. Considering that the mature schistosomin peptides found to date have similar sizes (79–83 aa), we believe that the ~14–16 kDa band detected by the antiserum consists of snail plasma schistosomin protein(s). Again, the size of mature schistosomin in snail plasma on the gel is larger than that predicted (~9 kDa). This may be due to post-translational processes such as glycosylation, or the inconsistent migration between protein markers and plasma proteins (see Fig. 3A and B).

3.3. Ontogenic expression of schistosomin in B. glabrata

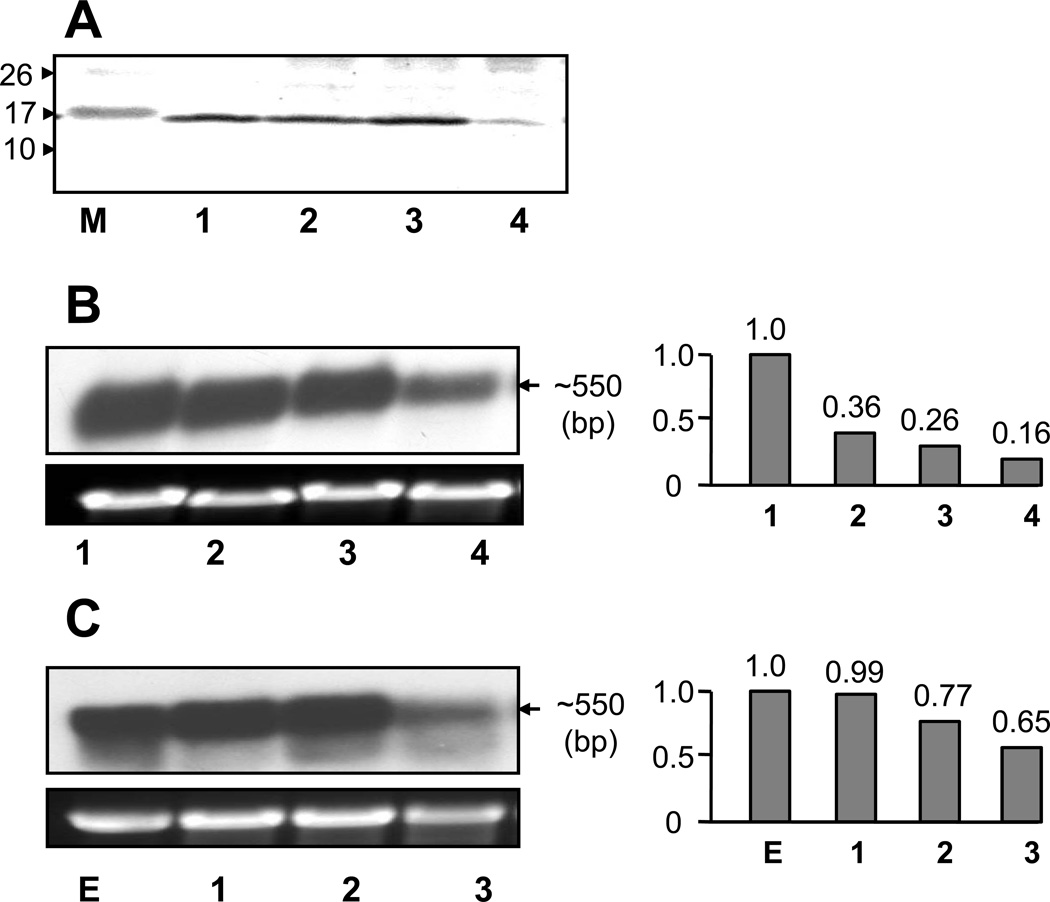

The four groups of different sizes of M line snails that were sampled were deliberately chosen to represent juvenile snails (2–5 mm), snails at the stage of sexual maturation (9–11 mm), fully mature snails (13–16 mm), and the oldest snails available from our culture (20–23 mm). Western blotting showed a relatively low expression level in the oldest snails, no significant variation was evident in expression levels of schistosomin in the other three groups (Fig. 4A). Further examination at the mRNA level with Northern blotting and qPCR confirmed this expression pattern (Fig. 4B). The expression pattern was also verified by examination of BS-90 B. glabrata of different ages, including a pooled sample of 1–10 day old embryos. Interestingly, a high expression level was observed in embryonic samples (Figs. 4B, C). The combined Northern and qPCR analyses showed a tendency for a decrease in expression from younger to older snails. At least, the results did not suggest upregulation in more aged snails. Taken together, our findings suggest schistosomin may play a role in snail’s development.

Fig. 4.

Ontogenic expression of schistosomin. (A) Plasma samples from M line B. glabrata were used for Western blotting. M: molecular weight (kDa). (B) RNA from whole bodies of M line snails was used for Northern blotting (left) and qPCR analysis (right). The approximate size of the M line snails from lane 1 to 4 in figures A and B were 2–4, 9–11, 13–16 and 20–23 mm shell diameter, respectively. Figures A and B show two independent experiments (using different pools of snails). The upper and lower panel show the mRNA bands hybridized to the schistosomin probe and the rDNA bands from the equal amount of total RNA samples loaded, respectively (applied to figure 4C and 5) (C) RNA from BS-90 embryos (lane 1) and whole bodies of the BS-90 snails (lane 2 to 4) was analyzed by Northern blotting (left) and qPCR (right), respectively. Lanes 2 to 4 represent BS-90 snails of 2–5, 8–10 and 13–16 mm, respectively.

3.4. Trematode infections do not elevate schistosomin expression

We first examined expression of schistosomin in M line snails following exposure to S. mansoni. Five time points of different days post-exposure (dpe) (i.e., 4, 15, 30, 45, and 60 dpe) were surveyed. All samples used for different time-points were derived from snails exposed to the same trematode batch; we sampled snails from a single group of exposed snails at the different dpes. Based on cercarial shedding from snails in the experimental group, we confirmed that about 95% of schistosome-exposed snails were infected. So at 4 and 15 dpe, most of snails (~95%) used should be infected although we could not determine the state of infection at those time points. In the case of S. mansoni-infection, shedding of cercariae normally occurs at 3 to 4 weeks post-exposure. Extensive production of parasites takes place in the snail host 3–4 weeks after infection. Three samples (30, 45, and 60 dpe) were derived from snails in which massive parasite production was taking place. Our data showed that expression levels of schistosomin from individual snails were variable. However, regardless of different days of post-infections examined (from 4 to 60 dpe), Western blots did not reveal obvious up-regulation of schistosomin as compared to the non-exposed M line individual snails of comparable size (Fig. 5A).

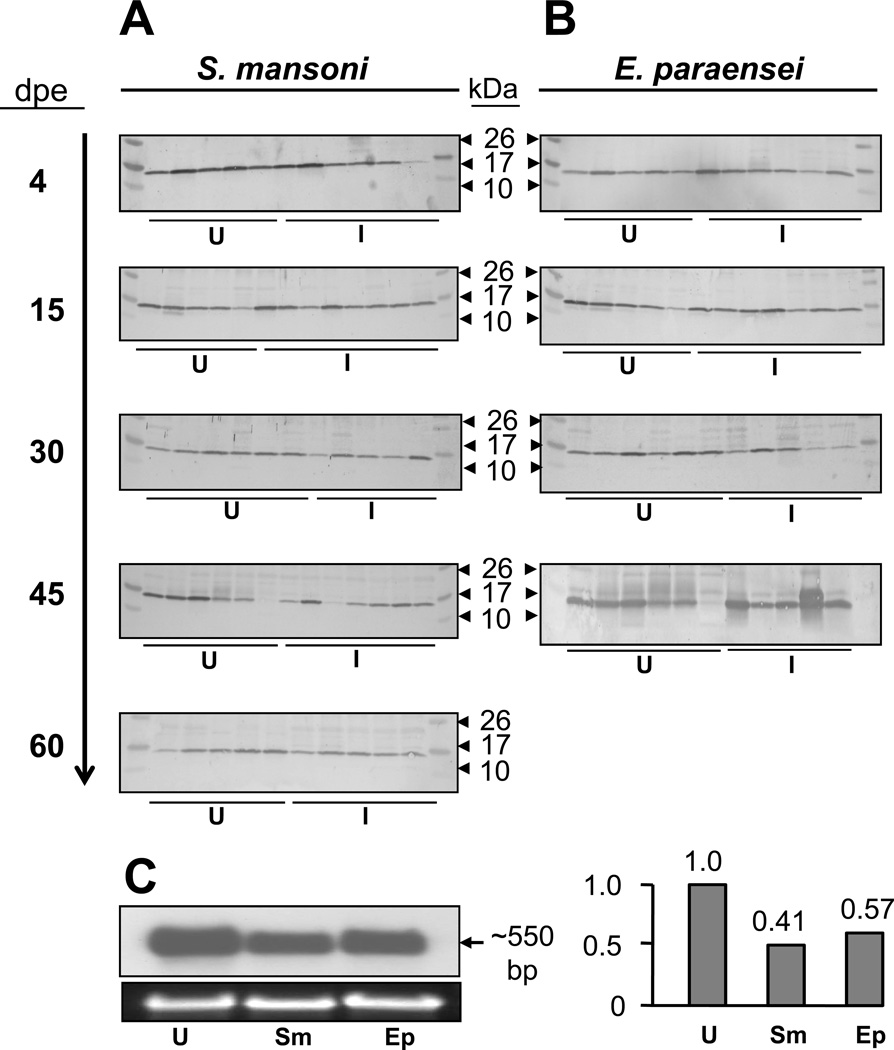

Fig. 5.

Western blots showing expression of plasma schistosomin in snails exposed to or infected with S. mansoni (A) or E. paraensei (B). In each blot"U” indicates unexposed individual snails and “I” indicates infected or exposed snails. (C) Northern blot (left) and qPCR (right) show the schistosomin mRNA expression from whole bodies of M line snails at a late stage trematode infection. Lanes 1, 2, and 3 contain RNA from comparably sized adult snails (13–16 mm), either not exposed (lane 1), or at 54 dpe to S. mansoni (Sm; lane 2) or to E. paraensei (Ep; lane 3).

Similar experiments were performed in M line snails after exposure to E. paraensei. All samples from 4 to 45 dpe were confirmed to be infected. No evidence suggests significant change of plasma schistosomin protein in the snails assayed (Fig. 5B).

To validate the Western blot data, we used Northern blotting and qPCR to investigate RNA samples from snails with patent infections. Our observations based on the two methods indicated that expression levels of schistosomin were lower in infected snails than in normal snails. Neither S. mansoni nor E. paraensei did induce increased expression of schistosomin (Fig. 5C).

Considering the possibility that a protein has multiple functions, we investigated whether microbial challenges could alter expression of schistosomin. Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus, Gram-negative bacterium E. coli, and yeast (S. cerevisiae) were used to test whether the microbes influence schistosomin expression. Northern analysis from RNA of the BS-90 snails at 6 and 12 hrs post-injection did not indicate that either of these microbes altered the expression of schistosomin (data not shown).

4. Discussion

To date, the four molluscan species (B. glabrata, L. stagnalis, P. acuta, and A. californica) found to possess schistosomin-like sequences all belong to the class Gastropoda. The sea slug A. californica (Opisthobranchia) is more distantly related to the other three species, which belong to the subclass Pulmonata [39]. Within this subclass, B. glabrata is more closely related to L. stagnalis than to P. acuta 40]. The schistosomin aa sequences do not reflect this phylogenetic relationship; the mature protein sequences of L. stagnalis and A. californica are more similar to each other than to the schistosomin of B. glabrata (see Fig. 2B). It is unknown why this sequence divergence has occurred, but the divergent B. glabrata schistosomin may differ functionally from the schistosomins of the other molluscs. Our study showed that schistosomin was expressed commonly from embryos to adult snails. Schistosomin transcripts are small (~550 nt), encoding a mature polypeptide sequence of only 79–83 aa, and should be commonly represented in ESTs. Indeed, 15, 4 and 3 schistosomin-like ESTs were identified in GenBank from A. californica, P. acuta, and B. glabrata, respectively. We did not find schistosomin homologs from EST datasets of several non-gastropod molluscan species such as oysters, scallops, and squid for which large numbers of EST sequences are available in the public databases [41–44]. Further BLAST searches did not reveal schistosomin-like sequences from non-mollusc species in the public databases. Based on the information currently available, it seems that schistosomins are unique to Gastropoda. Moreover, even within the Gastropoda, our blast searches using schistosomin aa sequence as a query failed to reveal genes encoding schistosomin-like proteins in the genome database for the mollusc Lottia gigantea (the only nearly completed mollusc genome currently available) (subclass Eogastropoda, Gastropoda) (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/cgi-bin/blastOutput?db=Lotgi1&jobId=1018351&jobToken=1242944591#seq11). This suggests that schistosomin might be an innovation within a narrow phylogenetic range in Gastropoda (more specifically, Euthyneura). Eogastropoda are divergent from Heterobranchia, which includes Euthyneura, in turn, comprised of Opisthobranchia and Pulmonata (http://www.tolweb.org/Gastropoda; [39]).

Previous studies involving the pond snail L. stagnalis demonstrated that schistosomin is an antagonist of snail hormones that regulate reproduction ([4, 5, 13]. In L. stagnalis, snail egg-laying is controlled by a set of gonadotropic neuropeptides. Among these peptides is caudodorsal cell hormone (CDH), an egg-laying hormone, which induces ovulation and egg laying [45]. The other hormone peptide, calfluxin, plays a role in stimulating the albumen gland [46]. Schistosomin inhibits the activity of CDH and decreases the binding capacity of calfluxin to membrane-bound receptors of the albumen gland [5, 6]. As a consequence, snail reproduction is inhibited. If schistosomin plays a direct role in reproduction, as an inhibitor of reproductive hormones, we might expect that the snail at reproductive ages should produce lesser amount of schistosomin. Our data for B. glabrata do not show this. The lowest expression level was observed in the very old snails, which normally stop laying eggs, and the reproductive hormone levels should be lowest. This seems in contrast to the inverse relation of schistosomin and reproduction, which was proposed in L. stagnalis. This suggests that schistosomin is not involved in downregulation of the B. glabrata reproduction. Conversely, we found relatively high expression levels in the embryonic and pre-reproductive stages, suggesting that more likely, schistosomin has a role during development/ontogeny.

Schistosomin is less likely to have a defense role since exposure to two trematodes, S. mansoni and E. paraensei, did not evoke changes in the expression levels observed from B. glabrata (for example, at 4 and 15 dpe). We also investigated effects of microbial challenges on B. glabrata schistosomin expression, and did not observe obvious changes of schistosomin mRNA levels between the sham-injected snails and the snails at 6 or 12 hours post-injection with either gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria, or yeast. Our data showed that no upregulated expression patterns of schsitosomin in exposed or infected snails (including patent infection), as compared to untreated controls, with qPCR analysis indicated that expression levels of schistosomin in snails with fully developed cercariae-producing infection were even lower than those of control snails. This suggests that in B. glabrata, trematode parasites do not increase expression of schistosomin, even during late stage infections (from 30 to 60 dpe) when B. glabrata harbors large numbers of developing parasites and suffers from parasitic castration [10, 12, 47, 48]. The unexpected observation of downregulation of schistosomin expression with age led us to propose a role of schistosomin in development/ontogeny. Infection (at least patent infection) may result in changes of developmental processes in snails such as aging through the downregulation of schistosomin expression, which was implied by the negative correlation between the schistosomin expression level and snail age/size (see Fig. 4B and C). These observations from trematode-infected snails lead us to conclude that B. glabrata schistosomin does not have a role in downregulating reproductive activities, as also supported by our ontogenic expression study. Our findings suggest that schistosomin is not involved in trematode-mediated parasitic castration in B. glabrata.

There are two plausible explanations for the discrepancies between our studies and those with L. stagnalis. First, this may be due to functional divergence of schistosomin between B. glabrata and L. stagnalis. Currently, it cannot be excluded that the schistosomins from B. glabrata reported here may be paralogous, not homologous to other molluscan schistosomins. However, given that two schistosomin aa sequences resulting from four schistosomin nt sequences have only one aa difference of the mature peptides (see Fig 1 and 2A) it is unlikely that they differ functionally in B. glabrata. It would be of interest to see whether schistosomin from A. californica may be involved in the parasitic castration since the schistosomins from A. californica are most closely related to that of L. stagnalis. Secondly, trematodes may use different strategies to bring about parasitic castration in different snail hosts (not always involving schistosomin) such as reproductive suppression by direct nutritional deprivation [49] or by modulation of host metabolic activities resulting in impaired acquisition or utilization of nutrients by snail reproductive organs [48]. With respect to the B. glabrata and S. mansoni model, ongoing genomic and transcriptomic studies for both should help resolve the specific mechanism for parasitic castration in this interaction. Efforts to date however, have not established a convincing link between parasitic castration and schistosomin (this study) or other molecules [49, 50] in B. glabrata.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants AI067686(S-MZ), AI024340 (ESL) and AI052363 (CMA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.De Jong-Brink M, Bergamin-Sassen M, Soto MS. Multiple strategies of schistosomes to meet their requirements in the intermediate snail host. Parasitology. 2001;123:S129–S141. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001008149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schallig DHFH, Hordijk PL, Oosthoek PW, et al. Schistosomin, a peptide present in the hemolymph of Lymnaea stagnalis nfected with Trichobilharzia ocellata, is produced only in the snail central nervous system. Parasitol Res. 1991;77:152–156. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoek RM, vanKesteren RE, Smit AB, et al. Altered gene expression in the host brain caused by a trematode parasite: neuropeptide genes are preferentially affected during parasitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14072–14076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hordijk PL, De Jong-Brink M, Termaat A. The neuropeptide schistosomin and hemolymph from parasitized snails induce similar changes in excitability in neuroendocrine cells controlling reproduction and growth in a freshwater snail. Neurosci Lett. 1992;36:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90047-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hordijk PL, Vanloenhout H, Ebberink RHM, et al. Neuropeptide schistosomin inhibits hormonally induced ovulation in the freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis. J Exp Zool. 1991a;259:268–271. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402590218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hordijk PL, Ebberink RHM, De Jong-Brink M, et al. Isolation of schistosomin, a neuropeptide which antagonizes gonadotropic-hormones in a freshwater snail. Eur J Biochem. 1991b;195:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Jong-Brink M, Hoek RM, Smith AB, et al. Schistosoma parasites evoke stress responses in their snail host by a cytokine-like factor interfering with neuroendocrine mechanisms. Netherlands J Zool. 1995;45:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Jong-Brink M, Hordijk PL, Vergeest DP, et al. The anti-gonadotropic neuropeptide schistosomin interferes with peripheral and central neuroendocrine mechanisms involved in the regulation of reproduction and growth in the schistosome-infected snail Lymnaea stagnalis. Prog Brain Res. 1992;92:385–396. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, et al. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper LA, Larson SE, Lewis FA. Male reproductive success of Schistosoma mansoni-infected Biomphalaria glabrata snails. J Parasitol. 1996;82:428–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ademo SA. Modulating the modulators: parasites, neuromodulators and host behavioral change. Brain Behav Evol. 2002;60:370–377. doi: 10.1159/000067790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blair L, Webster JP. Dose–dependent schistosome-induce mortality and morbidity risk elevates host reproductive effort. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Jong-Brink M, Saadany MEL, Soto MS. The occurrence of schistosomin, an antagonist of female gonadotropic-hormones, is a general phenomenon in hemolymph of schistosome-infected freshwater snails. Parasitology. 1990;103:371–378. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000059886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghavan N, Miller AN, Gardner M. Comparative gene analysis of Biomphalaria glabrata hemocytes pre- and post-exposure to miracidia of Schistosoma mansoni. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;126:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergote D, Bouchut A, Sautiere PE, et al. Characterisation of proteins differentially present in the plasma of Biomphalaria glabrata susceptible or resistant to Echinostoma caproni. Intl J Parasitol. 2005;35:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillou F, Mitta G, Galinier R. Identification and expression of gene transcripts generated during an anti-parasitic response in Biomphalaria glabrata. Dev Comp Immunol. 2007;31:657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lockyer AE, Spinks JN, Walker AJ, et al. Biomphalaria glabrata transcriptome: Identification of cell-signalling, transcriptional control and immune-related genes from open reading frame expressed sequence tags (ORESTES) Dev Comp Immunol. 2007a;31:763–782. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanelt B, Lun CM, Adema CM. Comparative ORESTES-sampling of transcriptomes of immune-challenged Biomphalaria glabrata snails. J Invertebr Pathol. 2008;99:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodall CP, Bender RC, Brooks JK. Biomphalaria glabrata cytosolic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) gene: Association of SOD1 alleles with resistance/susceptibility to Schistosoma mansoni. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;147:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphries JE, Yoshino TP. Schistosoma mansoni excretory-secretory products stimulate a p38 signalling pathway in Biomphalaria glabrata embryonic cells. Intl J Parasitol. 2006;36:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bender RC, Goodall CP, Blouin MS, et al. Variation in expression of Biomphalaria glabrata SOD1: A potential controlling factor in susceptibility/resistance to Schistosomin mansoni. Dev Comp Immunol. 2007;31:874–878. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshino TP, Dinguirard N, Kunert J, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of a tandem-repeat galectin from the freshwater snail Biomphalaria glabrata, intermediate host of the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Gene. 2008;411:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S-M, Adema CM, Kepler TB, Loker ES. Diversification of Ig genes in an invertebrate. Science. 2004;395:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1088069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S-M, Zeng Y, Loker ES. Characterization of immune genes from the schistosome host snail Biomphalaria glabrata that encode peptidoglycan recognition proteins and gram-negative bacteria binding protein. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:883–898. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang S-M, Nian H, Zeng Y, DeJong RJ. Fibrinogen-bearing protein genes in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: characterization of two novel genes and expression studies during ontogenesis and trematode infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008a;32:1119–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zahoor Z, Davies AJ, Kirk RS, Rollonson D, Walker AJ. Disruption of ERK signaling in Biomphalaria glabrata defence cells by Schistosoma mansoni: Implications for parasite survival in the snail host. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:1561–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stibbs HH, Owczarzak A, Bayne CJ, et al. Schistosome sporocyst-killing amebas isolated from Biomphalaria glabrata. J Invertebr Pathol. 1979;33:59–170. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(79)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loker ES, Hertel LA. Alterations in Biomphalaria glabrata plasma induced by infection with the digenetic trematode Echinostoma paraensei. J Parasitol. 1987;75:505–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winnepenninckx B, Backeljau T, Dewachter R. Extraction of high-molecular-weight DNA from mollusks. Trend Genetics. 1993;9:407–407. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90102-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y, Loker SM, Zhang S-M. In vivo and in vitro knockdown of FREP2 gene expression in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata using RNA interference. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;30:855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S-M, Zeng Y, Loker ES. Expression profiling and binding properties of fibrinogen-related proteins (FREPs), plasma proteins from the schistosome snail host Biomphalaria glabrata. Innate Immunity. 2008b;14:175–189. doi: 10.1177/1753425908093800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adema CM, Hertel LA, Miller RD, Loker ES. A family of fibrinogen-related proteins that precipitates parasite-derived molecules is produced by an invertebrate after infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8691–8996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, et al. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: Identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Briefing in Bioinformatics. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang S-M, Loker ES. Representation of an immune responsive gene family encoding fibrinogen-related proteins (FREPs) in the freshwater mollusk Biomphalaria glabrata, an intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni. Gene. 2004;341:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adema CM, Luo MZ, Hanelt B, et al. A bacterial artificial chromosome library for Biomphalaria glabrata, intermediate snail host of Schistosoma mansoni. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;(Suppl 1):167–177. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000900027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Z, Zhu B. Characterization and function of CREB homologue from Crassostrea ariakensis stimulated by rickettsia-like organism. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:1572–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knudsen B, Kohn AB, Nahir B, et al. Complete DNA sequence of the mitochondrial genome of the sea slug Aplysia californica: Conservation of the gene order in Euthyneura. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;38:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blair D, Davis GM, Wu B. Evolutionary relationships between trematodes and snails emphasizing schistosomes and paragonimids. Parasitology. 2001;123:S229–S243. doi: 10.1017/s003118200100837x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodson MS, Kojadinovic M, Troll JV, et al. Identifying components of the NF-kappa B pathway in the beneficial Euprymna scolopes Vibrio fischeri light organ symbiosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6934–6946. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6934-6946.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song L, Xu W, Li CH, et al. Development of expressed sequence tags from the bay scallop Argopecten irradians irradians. Mar Biotechol. 2006;8:61–169. doi: 10.1007/s10126-005-0126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanguy A, Guo XM, Ford SE. Discovery of genes expressed in response to Perkinsus marinus challenge in Eastern (Crassostrea virginica) and Pacific (C. gigas) oysters. Gene. 2004;338:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanguy A, Bierne N, Saavedra C, et al. Increasing genomic information in bivalves through new EST collections in four species: Development of new genetic markers for environmental studies and genome evolution. Gene. 2008;408:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebberink RHM, Van Loenhout H, Geraerts WPM, Joosse J. Purification and amino-acid sequence of the ovulation neurohormone of Lymnaea stagnalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7767–7771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dictus WJAG, De Jong-Brink M, Boer HH. A neuropeptide (calfluxin) is involved in the influx of calcium into mitochondria of the albumin gland of the fresh-water snail Lymnaea stagnalis. General Comp Endocrinol. 1987;65:439–450. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(87)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crew AE, Yoshino TP. Schistosoma mansoni: Effect of infection on the reproduction and gonal growth in Biomphalaria glabrata. Exp Parasitol. 1989;68:326–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crew AE, Yoshin0 TP. Influence of larval schistosomes on polysaccharide synthesis in albumin glands of Biomphalaria glabrata. Parasitology. 1990;101:351–359. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000060546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson SN. Redirection of host metabolism and effects on parasite nutrition. In: Beckage NE, Thompson SN, Federici BA, editors. Parasites and pathogen of insects. New York, New York: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bai FX, Johnston LA, Watson CO, et al. Phenoloxidase activity in the reproductive system of Biomphalaria glabrata: Role in egg production and effect of schistosome infection. J Parasitol. 1997;83:852–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]