Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) is reported here for the first time for Biomphalaria glabrata, the snail intermediate host for the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni. The fibrinogen-related protein 2 (FREP2) gene, normally expressed at increased levels following exposure to digenetic trematode parasites, such as S. mansoni or Echinostoma paraensei, was targeted for knockdown. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) corresponding to specific regions of the FREP2 gene was introduced into snails by direct injection into the hemolymph, 2 days prior to exposure to trematodes, or added to co-cultures of B. glabrata embryonic (Bge) cells and E. paraensei sporocysts. After introduction of FREP2 dsRNA, expression levels of FREP2 were significantly reduced, to 20–30% of control values. In addition, we were able to disrupt expression of the house-keeping myoglobin gene, further confirming the feasibility of RNAi for B. glabrata. Cross-reactivity in RNAi has not been observed either among four FREP gene subfamilies or between FREP2 and myoglobin. Establishment of RNAi techniques in B. glabrata provides an important tool for clarifying the function of genes believed to play a role in host-parasite interactions, specifically between B. glabrata and its trematode parasites, including S. mansoni.

Keywords: RNA interference (RNAi), Fibrinogen-related protein (FREP), Biomphalaria glabrata, Echinostoma paraensei, Schistosoma mansoni, Host–parasite interactions, Innate immunity, Comparative immunology

1. Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is a process by which the introduction of exogenous double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) corresponding to a specific messenger RNA (mRNA) sequence results in a significant reduction in level of the targeted mRNA [1–3]. This technique is a powerful post-transcriptional gene silencing technique that is providing insight into gene function in plants and animals [4–8]. RNAi has been used to assess gene function in invertebrates and vertebrates under in vivo and in vitro conditions. Most in vivo RNAi studies have been performed with invertebrates, mainly arthropods, with the aim of directly assessing phenotype changes. These invertebrates include Caenorhabditis elegans [9,10], digenetic trematodes [11,12], silkworms [13], moth Spodoptera liturs [14], Drosophila [15–17], mosquitoes [18,19], honeybee [20], and ticks [21]. In vitro RNAi assays have also been widely applied to cell lines from humans and model organisms such as C. elegans [10], Drosophila [22,23], mosquitoes [24], and mice [25,26].

Successful application of RNAi in a broad range of eukaryotic organisms suggests that it may be possible to employ this promising technique in mollusks. Indeed, RNAi has been reported to disrupt neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) gene function in the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis [27], and to inhibit the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein gene (ApC/EBP) in the marine mollusk Aplysia [28]. However, RNAi has not yet been reported in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata, a widely studied intermediate host of the trematode Schistosoma mansoni. This helminth infects 83 million people worldwide [29]. B. glabrata is used as a model to explore the nature of the defense responses of snails to digenetic trematodes like S. mansoni and Echinostoma paraensei. A large, diverse family of hemolymph proteins termed fibrinogen-related proteins, or FREPs is present in B. glabrata [30,31]. Previous work suggests that FREPs are involved in molluscan internal defense because they are capable of precipitating soluble trematode antigens and binding to trematode sporocysts. Although considerable data on the structure, diversity, and expression of FREPs have accumulated recently [32–36], the precise roles of FREPs in defense and perhaps other aspects of snail physiology require further clarification. Classical genetic knockout techniques are not presently available in mollusks, nor are they likely to soon be developed. RNAi could serve as a powerful alternative tool to assess snail gene function in both in vivo and in vitro studies. Towards this end, we here report our studies to develop RNAi to knockdown expression of FREP genes in B. glabrata, as a necessary prelude to exploring their role in anti-trematode defense.

FREP2, a member of FREP gene family, was chosen as a target gene because its transcripts appear in greater abundance in individuals of the M line strain of B. glabrata after exposure to either E. paraensei or S. mansoni, and in snails of the BS-90 (also called Salvador) strain after exposure to S. mansoni [36]. In addition, FREP2 has a relatively simple gene structure with one immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) domain [32]. Moreover, like all FREPs currently known, FREP2 is comprised of both a specific IgSF region and a more conserved fibrinogen (FBG) region. This provides a useful opportunity to assess the specificity of dsRNAs targeted to these regions in the RNAi experiments described below.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Parasites, Bge cells and snails

The life cycles of S. mansoni and E. paraensei were maintained in the laboratory as described by Stibbs et al. [37] and by Loker and Hertel [38], respectively. The B. glabrata embryonic (Bge) cells originally established by Hansen [39] were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL 1494). Bge cells were maintained at 26 °C in complete Bge cell medium [39], supplemented by 50 µg/µl gentamicin sulfate (Sigma) and 5% fetal bovine serum (FCS) (Sigma) as described by Coustau et al. [40]. The BS-90 andMline strains of B. glabrata were maintained in the laboratory [39].

2.2. Co-culture of E. paraensei miracidia/sporocysts and Bge cells

Bge cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well (500 µl culture medium) in a 24-well plate for 1 day prior to addition of dsRNA (or 5 µl nuclease-free water for the control). Miracidia were added 2 days after the addition of dsRNA or nuclease-free water. To maintain physical separation between the Bge cells and parasites, E. paraensei miracidia were added in sterile plastic inserts (0.4 µm membrane pore size; Corning Incorporated, NY, USA), and co-cultured with Bge cells in the same well. After co-culture for a specified number of days, the parasites were removed and Bge cells were collected for RNA extraction.

2.3. dsRNA synthesis

FREP2 dsRNA was synthesized following the method of Clemens et al. [22]. Sequence-specific primers were designed from FREP2 cDNA sequences (GenBank accession No. AY012700). The primers used for generating FREP2 dsRNA (537 bp) were: forward 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCGCTACCACTTCGACTTGTT-3′, reverse 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGTGGGACTGGCTCTTGATAT-3′.The sequence underlined is T7 promoter sequence (same for myoglobin primers below). The primers span the region that encodes the signal peptide (SP), IgSF, and interceding region (ICR) of FREP2, a region known to be specific to this particular FREP gene [35]. A full-length FREP2 cDNA was cloned from M line snails and the sequence was confirmed by sequencing. Using these primers, this specific sequence was amplified from the FREP2 cDNA template and purified using the High pure PCR purification kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). dsRNA was synthesized from these purified templates using the MEGAscript RNAi kit (Ambion). Synthesized dsRNA was dissolved in nuclease-free water and stored at −20 °C and its integrity was routinely verified by non-denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis.

Myoglobin, a house-keeping gene [41] whose expression would not be expected to change as a consequence of exposure to trematode infection, was chosen as a control. Myoglobin dsRNA (541 bp) was synthesized in the same manner as described above. The primers designed from Gen-Bank accession number U89283 were: forward primer 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACAACCAGCCCAACTGAAA-3′, and reverse primer 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGTGGGCGAATAATGACTTT-3′. The forward and reverse primers are in the 5′UTR (untranslated region) and 3′UTR, respectively [41]. The cDNA template for synthesis of the myoglobin dsRNA was cloned from BS-90 snails.

2.4. Introduction of dsRNA into snails

Regardless of the amount of dsRNA applied, the volume for all injections was 5 µl throughout this study. For sham injections, the same amount of nuclease-free water was injected. Snails of 6–9 mm shell diameter were used. Injections were made into the post-renal sinus just anterior to the digestive gland, using a BD Ultra-FineTM II syringe, needle G 31 (BD Consumer Healthcare, New Jersey, USA). Two days after introduction of dsRNA, snails were exposed individually to ~30 miracidia of S. mansoni or E. paraensei, depending on the strain of snails used (i.e., BS-90 for S. mansoni; M line for E. paraensei). For the combination of M line snails and E. paraensei, the status of infection was checked under a dissecting microscope. Only snails with sporocysts visible in the heart were considered as “infected” and used for RNA extraction. Total RNA samples were extracted from the whole body of snails. Five snails were used for each treatment within each separate experiment. We first investigated different doses of FREP2 dsRNA on RNAi knockdown of FREP2 transcript abundance. BS-90 snails were injected with 0.1, 1.0 and 5.0 µg per snail of FREP2 dsRNA.

In vitro RNAi was attempted by introduction of dsRNA into the Bge cultures, followed by exposure to E. paraensei. Five µg dsRNA (dissolved in 5 µl nuclease-free water), or 5 µl nuclease-free water as a control, were added directly to the culture medium in each well. About 2000 miracidia of E. paraensei were loaded per well at two days after addition of dsRNA. Total RNA was extracted from the Bge cells at 1, 2, 4, and 6 days after addition of miracidia (i.e., 3, 4, 6, and 8 days post-introduction of dsRNA).

2.5. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from Bge cells or the whole body of individual snails using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (BD Biosciences). cDNA was generated using random hexamers from the total RNA samples (ThermoScript RT-PCR kit; Invitrogen).

2.6. Real-time quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to monitor the quantitative expression of FREPs and myoglobin genes. qPCR primers were designed using Primer Express 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems). All primers used for qPCR assay are listed in Table 1. In order to avoid amplification and detection of injected dsRNA, the qPCR primers were designed to amplify regions that did not overlap with the regions targeted by dsRNA. Since FBG of FREP2 has no introns, additional primers which span intron 3 (at the ICR region) were used to monitor genomic contamination (Table 1). 18S rDNA was used as an internal reference for qPCR, as described by Hertel et al. [36]. To test the specificity of RNAi, qPCR was also performed for FREPs, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 13.

Table 1.

Primers used for qPCR

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | GenBank No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| FREP2 | Forward | TGGAATTACTAAGAGTGTTACGTTTACTGA | AY012700 |

| Reverse | GGGTTTTCCCACTTAATCTAG TTCTATTT | ||

| FREP2* | Forward | GCTGTAGCTCTGAGTTATATACAAGATCGT | AY012700 |

| Reverse | GGCTCT TGATATTTGAATGCTATCC | ||

| FREP3 | Forward | CAATCTTTC AACTGCCTCGATAAA | AY028461 |

| Reverse | GGGTGGATAGCTCATTTTGCTT | ||

| FREP4 | Forward | AAGAAAATCATTTAGCAGCCTTGAG | AY012701 |

| Reverse | GCAAGACAGTTGCAGGTTTTTGT | ||

| FREP6 | Forward | ATGGATAAACCCAGGCTTACGAA | AY012702 |

| Reverse | CACGTTTCTCTTAATGTTACAATTCATGAT | ||

| FREP7 | Forward | CGT CTGGTTTTCTTCCAATCTTTATT | AY028462 |

| Reverse | TCTGGTTGGACATCAATGACAAG | ||

| FREP13 | Forward | CAACTGCCTTAATGGAAGTAAAAAATC | AF515468 |

| Reverse | AGATGT TATTTGATCGTCTCCCTTTC | ||

| Myoglobin | Forward | GGAATTCATGCAATCAATGCA | U89283 |

| Reverse | TCT CTTTAATGTTTTCGCAGATCTTC | ||

| 18S rDNA | Forward | CGCCCGTCGCTACTATCG | U65224 |

| Reverse | ACGCCAGACCGAGACCAA |

Note: FREP2* primers located at the interceding region (ICR) of FREP2 were used to check for absence of contamination with genomic DNA.

qPCR was carried out on a Sequence Detection System 7000 (Applied Biosystems) using a SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents kit (Applied Biosystems), as used previously to assess differential expression of FREPs [36]. To quantify expression level of the target genes (FREP2 and myoglobin), the synthesized cDNA used for qPCR was diluted 10-fold with nuclease-free water. For the 18S rDNA (internal reference gene), 1000-fold dilution was used for qPCR because of the high number of 18S rDNA copies. For each primer/cDNA sample combination, qPCR reactions were performed in duplicate. Twenty-five µl of qPCR reaction mixture contained the following reagents: cDNA derived from 20 ng total RNA for FREP2 or myoglobin amplification, or cDNA derived from 0.2 ng total RNA for 18S rDNA amplification; 1 × SYBR Green PCR buffer, 250 µM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and 500 µM dUTP, 3mM MgCl2, 0.1 µM of primers, and 0.625U AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase. Cycling parameters were: 1 cycle of 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 58 °C for 1 min. Dissociation curves were analyzed at the end of each run to determine the purity of product and specificity of amplification.

2.7. Northern blots

For each of the three groups to be compared, 45 µg total RNA was obtained by pooling from extractions from the whole bodies of ten individual BS-90 snails. RNA was separated on a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel. Electrophoresis and RNA transfer, hybridization, and blot-washing were performed according to the supplier’s instruction (NorthernMaxTM System, Ambion) with modifications suggested by Zhang and Loker [35]. The FREP2 probe used in this study is identical to the FREP2 probe previously used [35]. The probe sequence overlaps the region from which dsRNA of FREP2 was derived. In addition to loading the same amount of RNA per lane, the staining intensity of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was used as a standard to assure that equal amount of RNA was loaded in each lane.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Relative gene expression data were obtained using the ΔΔCt method [42], using 18S rDNA as the internal standard. The formula is: Fold change = 2−[ΔΔCt], where ΔΔCt = (Cttarget−Ct18S)treatment − (Cttarget − Ct18S)control. Each threshold value Ct is the mean of duplicate measurements. Before using the ΔΔCt method for quantitation, validation experiments were performed according to the sequence detection system user bulletin #2 (Applied Biosystems) to demonstrate that efficiencies of target amplification and reference 18S rDNA amplification were approximately equal.

All data were analyzed using statistical software SPSS10.3. Independent sample t-tests were used to determine FREP2 expressional differences between dsRNA-treated groups and their corresponding non-dsRNA treated groups in both in vivo and in vitro experiments at various times of post-dsRNA treatment. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze induction of the FREP2 expression in Bge cells, BS-90 and M line snails at various times post-exposure to parasites. Effect of different doses of FREP2 dsRNA on knockdown of FREP2 expression in BS-90 snail, induction of FREP2 expression in Bge cells after exposure to different numbers of sporocysts and expression change of myoglobin gene in BS-90 snails at various times after introduction of myoglobin dsRNA were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Post hoc multiple comparisons were made using Fischer’s least significant difference test. Differences were considered as significant at P < 0:05.

3. Results

3.1. Validation of qPCR experiments by ΔΔCt method

For the ΔΔCt method to be valid, the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes should be approximately equal. A sensitive method for assessing if two amplicons have the same efficiency is to examine the correlation between ΔCt (Cttarget − Ct18S) and several dilutions of template cDNA [42]. A plot of the log cDNA dilution versus ΔCt was generated for each target gene tested (plots not shown). The slopes (b) of regression lines for FREPs 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 13, and myoglobin were −0.049, −0.068, 0.075, 0.054, 0.042, 0.094, and −0.068, respectively. The absolute values of all slopes obtained were smaller than 0.1 (|b| <0:1), suggestive of equivalent efficiencies of amplification [42]. Therefore, ΔΔCt calculation was used for the relative quantification of target genes selected in this study.

3.2. Knockdown of FREP2 expression in BS-90 snails

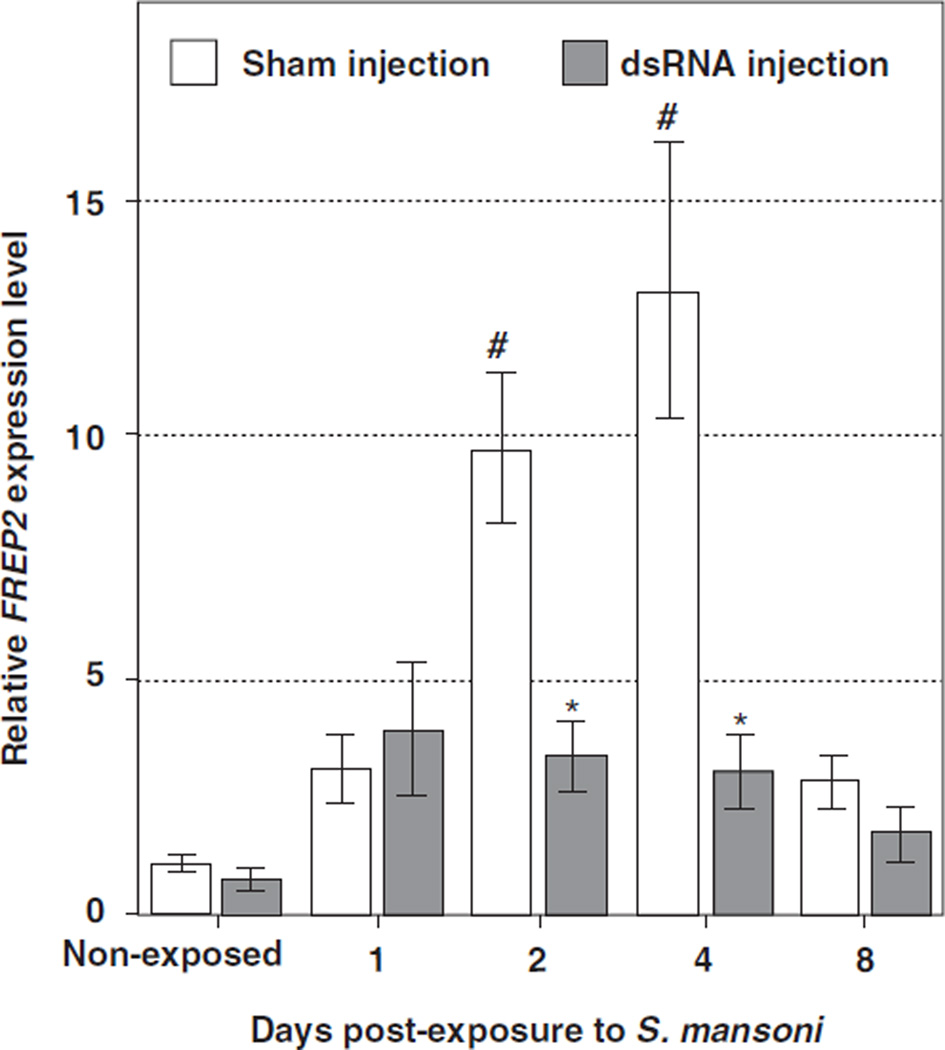

For this study, two snail-parasite combinations were chosen to determine if RNAi could be documented for the FREP2 gene. The initial experiments were done with BS-90 snails exposed to S. mansoni. Fig. 1 shows that, compared to uninfected controls, significant increases occurred in FREP2 expression in BS-90 snails at 2 days post-exposure (DPE) to infection (9.7±1.6 fold increase, P <0:01) and at 4 DPE (13.1±2.9 fold increase, P <0:01). This trematode-provoked increase in host FREP2 transcript abundance thus provided a good target for which to test protocols to achieve knockdown.

Fig. 1.

Effect of timing on knockdown of FREP2 expression in BS-90 snails after exposure to S. mansoni. Open bars show FREP2 expression levels at different days post-exposure (DPE). The symbol “#” indicates a significant elevation (P<0:01) of expression of FREP2 in the sham-injected snails at the given time point post-exposure to the parasite, relative to non-exposed, sham-injected snails. Filled bars show the expression of FREP2 after introduction of dsRNA (5 µl at 1µg/µl). In this experiment snails were exposed to S mansoni at 2 days post-injection (DPI). An “*” indicates a significant reduction (P < 0:05) in FREP2 expression in snails injected with dsRNA compared to sham-injected snails at the same time post-exposure to the trematode.

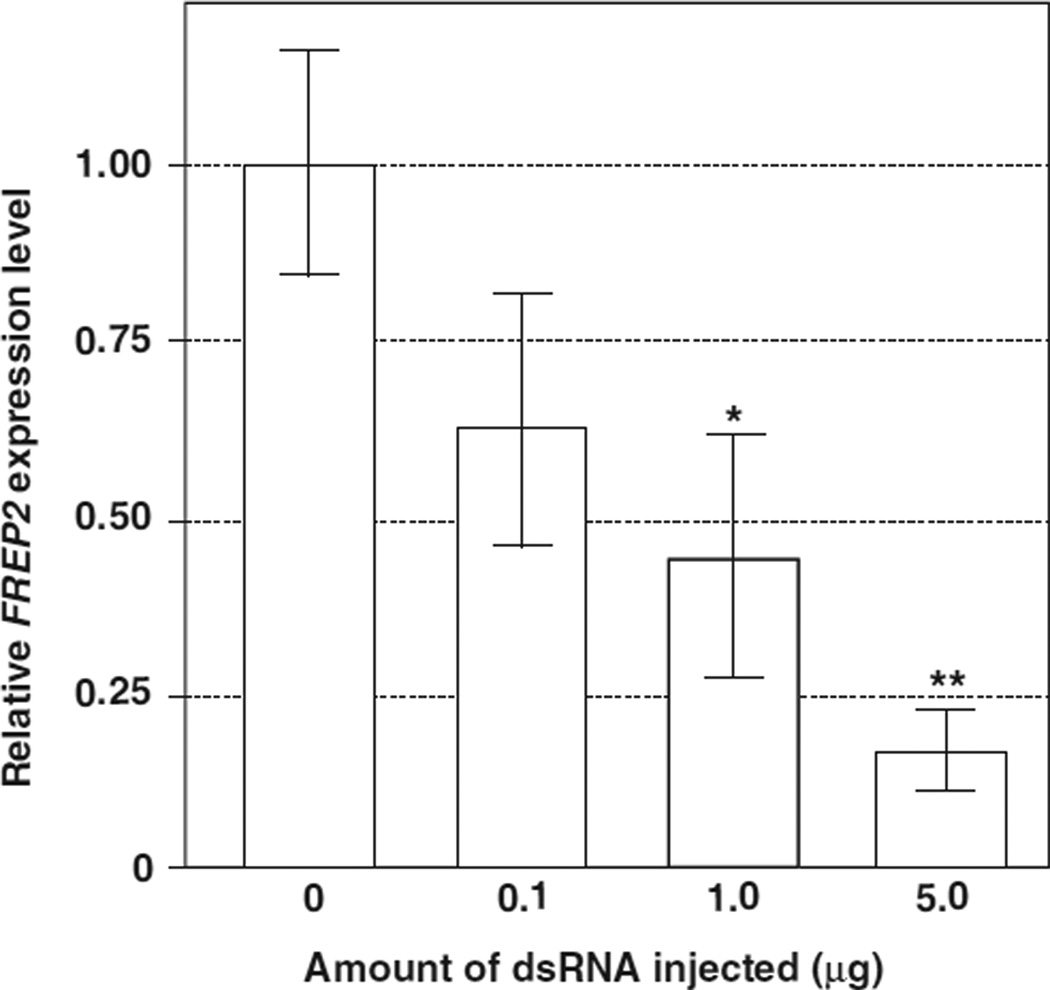

At 2 days post-injection (DPI), the snails were exposed to S. mansoni. FREP2 transcript abundance at 4 DPE was significantly reduced compared to controls when individual snails were injected with dsRNA at a dose of 1 µg (43.7±17.4% of control, P <0:05) or 5 µg (16.5±5.8% of control, P <0:01) (Fig. 2). We, therefore, chose the dose of 5 µg per snail for our further RNAi experiments.

Fig. 2.

Effects of different doses of FREP2 dsRNA on knock-down of FREP2 expression in BS-90 snails after exposure to S. mansoni. Snails were injected with different doses of dsRNA, followed by exposure to 30 S. mansoni miracidia at 2 DPI of dsRNA. RNA was extracted from the snails at 4 DPE. Five snails (n = 5) were used in each experiment. The symbols “*” and “**” indicate P < 0:05 and P < 0:01, respectively.

To determine the temporal dynamics of RNAi knockdown, dsRNA was injected into snails and at 2 DPI the snails were exposed to S. mansoni. Expression levels were found to be significantly decreased compared to snails that were exposed to the parasites but not injected with dsRNA. On 2 and 4 DPE, the expression levels were 34.3 ± 7.3%, and 22.9 ± 5.9% relative to controls (i.e., no dsRNA injected; P<0:05) (Fig. 1).

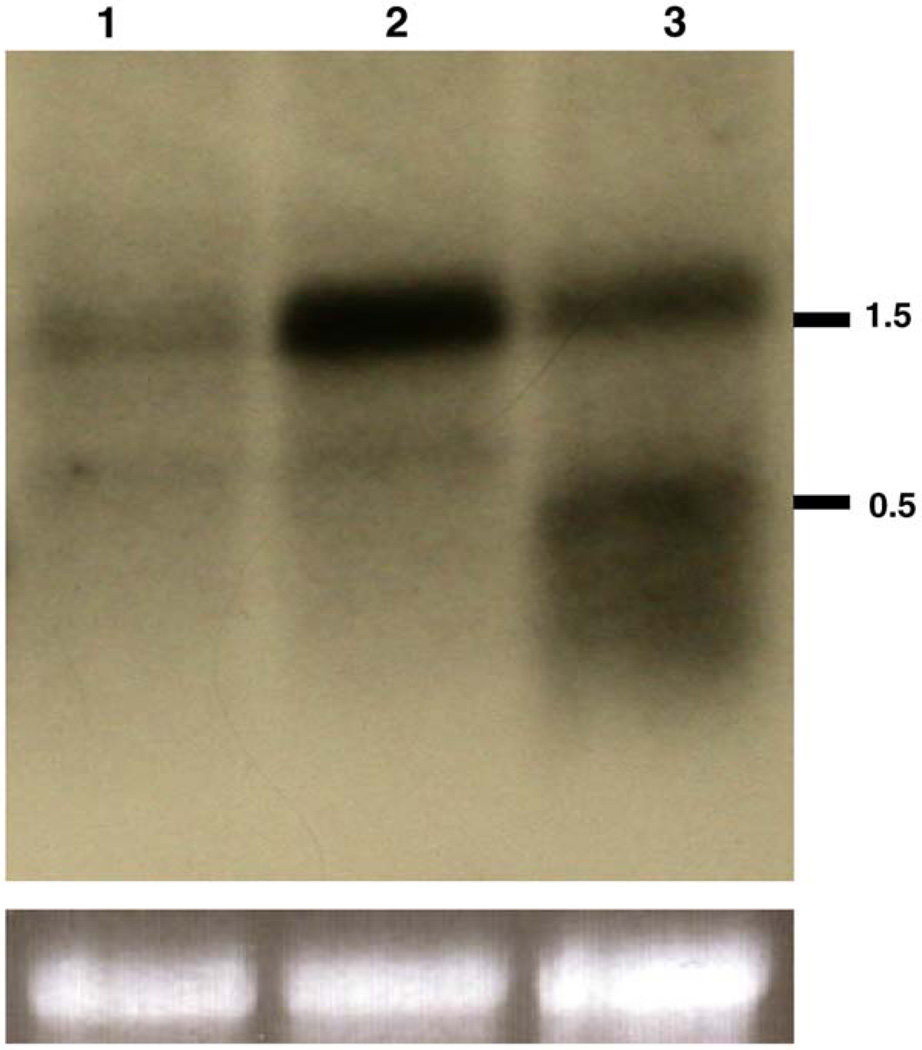

To further confirm that RNAi had been achieved, we performed Northern blot analysis to monitor changes in FREP2 expression. We examined RNA samples from control snails and snails exposed for 2 days to S. mansoni that had been treated with dsRNA or not. Compared to controls, FREP2 expression in snails exposed to S. mansoni was much higher than that of normal snails. In RNAi-treated snails, the expression level was obviously diminished compared to the snails that were exposed to parasites but received no dsRNA (Fig. 3). The pattern noted was thus consistent with data generated by qPCR. Unexpectedly, in addition to FREP2 message, a fuzzy band of a size equivalent to, and smaller than, that of injected dsRNA was noted on the blot.

Fig. 3.

Northern blot analysis showing RNAi effect in BS-90 snails. Lane 1 shows RNA from control snails at 4 days post sham-injection. Lanes 2 and 3 represent RNA from snails that were either sham-injection (lane 2) or injected with dsRNA (lane 3), followed by exposure to S. mansoni for 2 days (i.e., 4 DPI). For each lane, total RNA was pooled from the whole bodies of 10 snails. The upper image shows the intensity of FREP2 probe binding to mRNA. The lower photos show the staining intensity of rRNA from lanes, as loading controls. Approximate molecular sizes (kilobase) are indicated on the right.

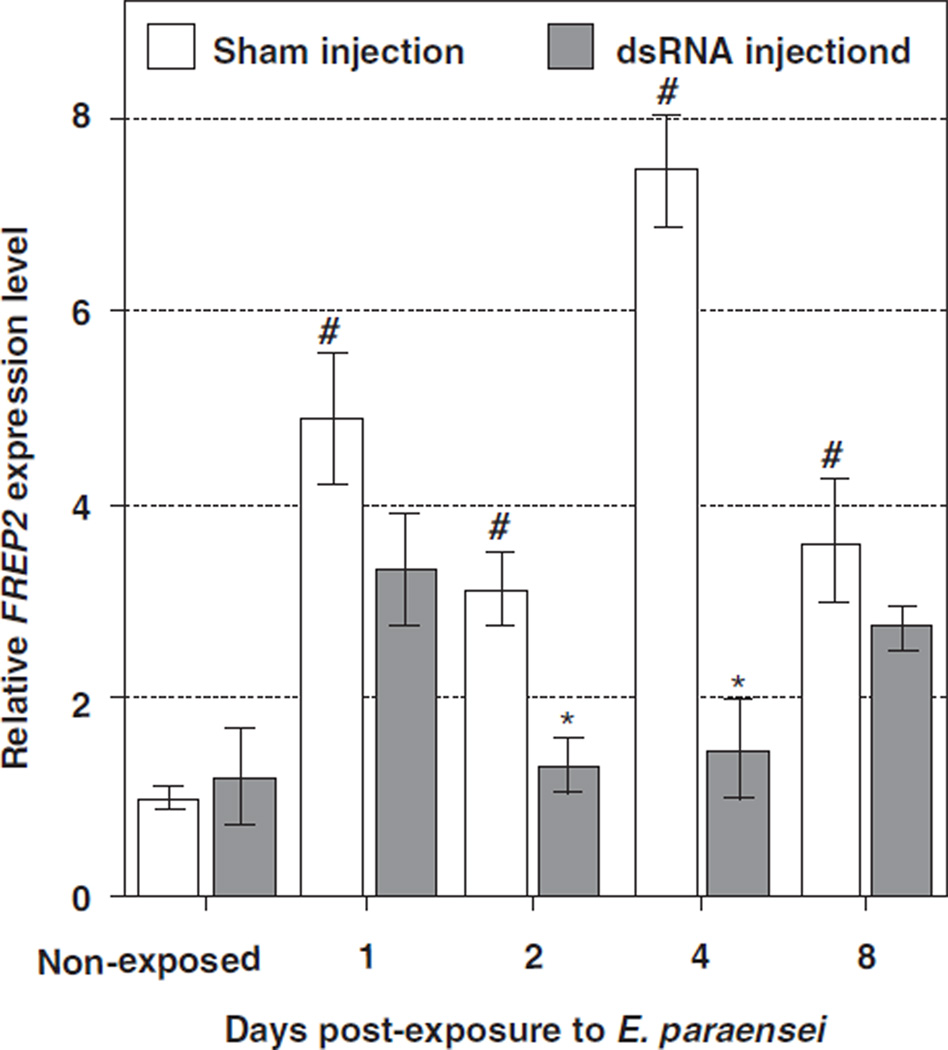

3.3. Knockdown of FREP2 expression in M line snails

Using the same approach as described in Section 3.2, we examined the effect of RNAi on FREP2 abundance in M line snails. First, FREP2 expression was shown to be elevated in M line snails at 1, 2, 4, and 8 DPE to E. paraensei (4.9 ± 0.7, 3.1 ± 0.4, 7.5 ± 0.6, and 3.6 ± 0.6 fold increases relative to non-exposed controls, respectively, all P < 0:01) (Fig. 4). This confirmed that E. paraensei exposure activated FREP2 expression.

Fig. 4.

Effect of timing on knockdown of FREP2 expression level in M line snails after exposure to E. paraensei. Open bars show FREP2 expression levels in M line snails. The symbol “#” indicates a significant elevation (P < 0:01) of expression of FREP2 in the sham-injected snails at the given time point post-exposure to E. paraensei, relative to non-exposed, sham-injected snails. Filled bars show the expression of FREP2 after introduction of FREP2 dsRNA (5 µl at 1µg/µl). Snails were exposed to E. paraensei at 2 DPI. An “*” denotes a significant reduction (P < 0:05) in FREP2 expression in snails injected with dsRNA, compared to sham-injected snails at the same time post-exposure to the trematode.

For experimental snails, 5 µg FREP2 dsRNA was injected followed 2 days later by exposure to E. paraensei. Controls were sham-injected and then exposed to E. paraensei at the same time. FREP2 expression in experimental snails was observed to be significantly reduced at 2 DPE (42.2 ± 9.9% of controls, P < 0:01) and 4 DPE (20.0 ± 6.9% of controls, P < 0:01) (Fig. 4). The largest RNAi effect was seen at 4 DPE. These results generally agree with the findings observed in the BS-90 snails.

3.4. Knockdown of FREP2 expression in Bge cells

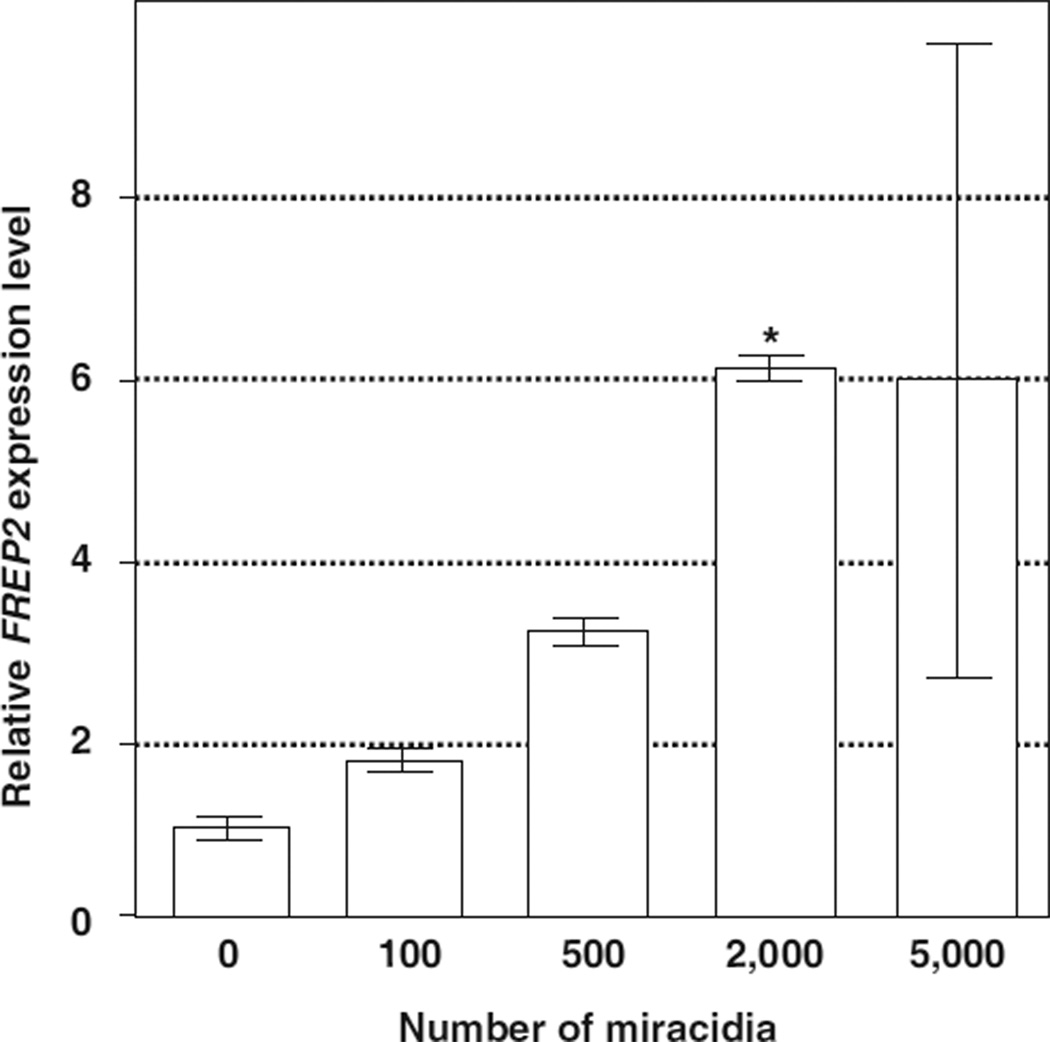

In vitro RNAi experiments were conducted in Bge cells, the only available B. glabrata cell line. Like the in vivo RNAi studies described above, we first determined whether exposure to E. paraensei miracidia/sporocysts was able to heighten FREP2 expression in the Bge cells, and how many parasites are required for the activation. As shown in Fig. 5, there is a positive correlation between the number of miracidia added to cultures and the level of FREP2 expression observed in Bge cells. The expression levels observed from the cells that were co-cultured with 2000 miracidia was significantly higher than that of the non-exposed control cells (P < 0:05).

Fig. 5.

Induction of FREP2 expression in Bge cells after exposure to different numbers of E. paraensei miracidia. Bge cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in 500 µl medium, one day prior to addition of parasites. Parasites were in inserts to maintain separation between them and the Bge cells. RNAs was extracted from the cells 4 day after addition of parasites. An “*” indicates significance when compared to control (P < 0:05). Three wells were used for each treatment.

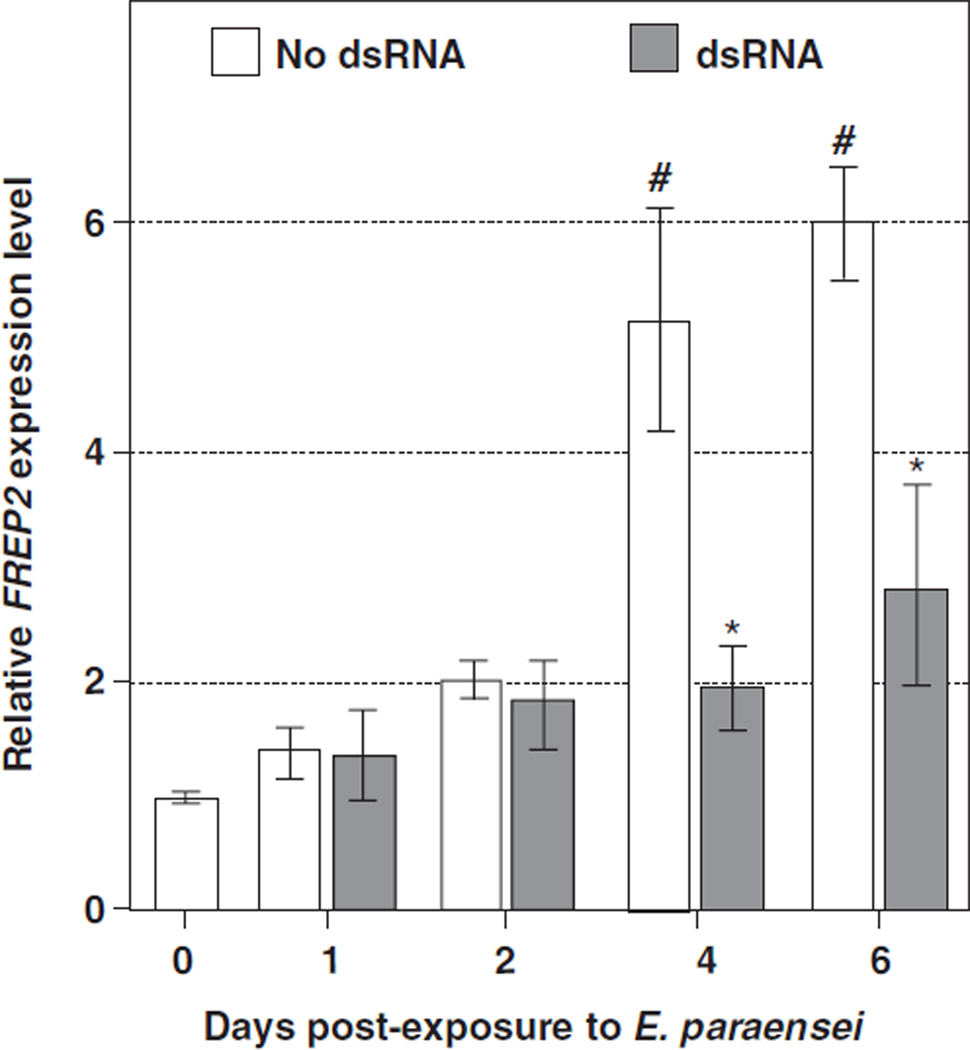

This was followed by experiments to determine the timing of FREP2 expression after exposure to the parasite. FREP2 expression was significantly increased at 4 and 6 days post-addition of 2000 miracidia (5.2 ± 1.0 and 6.0 ± 0.5 fold of the non-exposure control, respectively; both P < 0:01) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of FREP2 expression level in Bge cells after exposure to E. paraensei. Bge cells were seeded as described in Fig. 5. After one day of cell culture, 5 µg FREP2 dsRNA was applied to the culture medium. Two thousand miracidia were added 2 days after the dsRNA. Bge cells were harvested at different DPE, i.e., 1, 2, 4 and 6 days for RNA extraction. Open bars show FREP2 expression levels in the Bge cells at different DPE. The symbol “#” indicates significant elevation (P < 0:01) of expression of FREP2 in the sham-injected snails at the given time point post-exposure to the parasite, relative to the non-exposed cells. Filled bars show the expression of FREP2 after introduction of FREP2 dsRNA (5 µl per well). An “*” denotes a significant reduction (P < 0:05) in FREP2 expression in the cells in which the FREP2 dsRNA was added compared to cells at the same time post-exposure to the trematode, but with no involvement of RNAi. The analysis was based on three independent wells for each experiment.

After introduction of dsRNA to the Bge cultures, followed by exposure to E. paraensei, significant decreases of FREP2 expression were observed at 4 DPE (38.2 ± 6.8% of non-RNAi treated control, P < 0:05) and 6 DPE (46.9 ± 14.8% of non-RNAi treated control, P < 0:05).

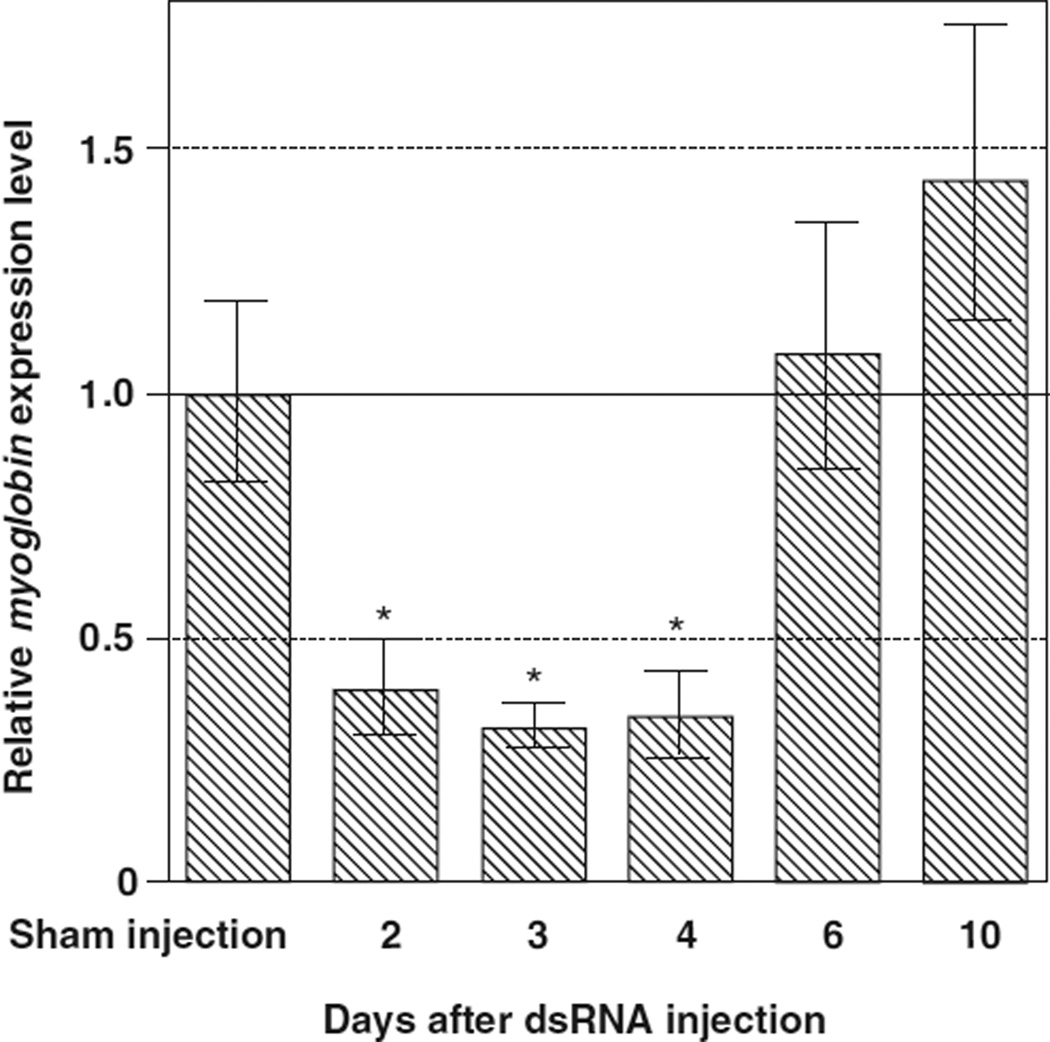

3.5. Knockdown of myoglobin expression in BS-90 snails

Injection of myoglobin dsRNA resulted in significant decreases of myoglobin expression in BS-90 snails at 2, 3 and 4 DPI (i.e., 40.0 ± 9.3%, 31.9 ± 4.3% and 34.1 ± 8.5% of control levels, respectively, all P < 0:05) compared to sham-injected controls (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Expression of myoglobin in BS-90 snails was reduced after introduction of myoglobin dsRNA (5 µl at 1µg/µl). The sham-injection (control) was conducted in each experiment, and the expression value is presented by a solid horizontal line indicated by 1.0 in the figure. An “*” indicates a significant reduction (P < 0:05) in myoglobin expression relative to non-RNAi treated snails at 2, 3 and 4 DPI.

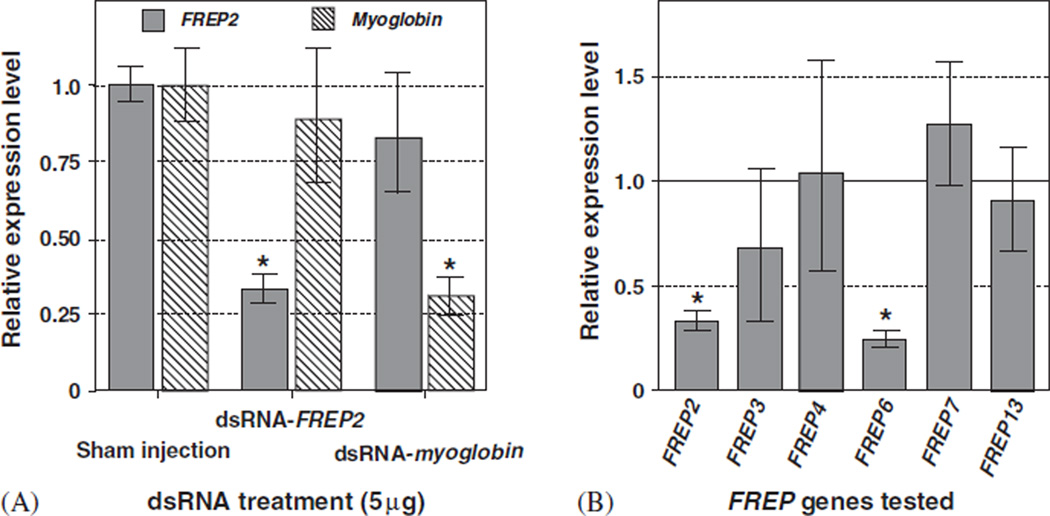

3.6. Specificity of RNAi in snails

To test the specificity of RNAi, BS-90 snails were injected with FREP2 dsRNA, myoglobin dsRNA or nuclease-free water 2 days before exposure to S. mansoni miracidia. We detected significant reduction in expression of the targeted gene level at 4 DPE, but no RNAi effect was observed for the non-target gene (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Specificity of RNAi effects in B. glabrata. (A) RNAi cross-reactivity did not occur between myoglobin and FREP2 in BS-90 snails. The injection of FREP2 dsRNA resulted in a significant reduction in FREP2 expression (*P < 0:01) compared to sham-injected controls, whereas myoglobin expression was not significantly altered. Conversely, the injection of myoglobin dsRNA resulted in a significant reduction in myoglobin expression (*P < 0:01) compared to sham-injected controls, whereas FREP2 expression was not significantly reduced. As before, all snails were exposed to S. mansoni at 2 DPI of dsRNA or of nuclear-free water (sham-injection). qPCR data were collected at 4 DPE (i.e., 6 DPI). (B) Expression level of FREP genes (FREPs 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 13) in BS-90 snails after injection of dsRNA of FREP2 (5 µg per snail). There were two groups of snails, one injected with FREP2 dsRNA (5 µg) and the other sham-injected as a control. Five snails were analyzed in each group by qPCR. We divided the expression values for each FREP gene by their corresponding control expression value. Accordingly, the control expression for each gene is 1 (presented by a solid horizontal line indicated by 1.0 in the figure). Values <1 represent downregulation and values > 1 represent upregulation. *P < 0:01.

Further RNAi off-target experiments were performed using members of the FREP gene family. The expression of six FREP genes, i.e., FREPs 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 13, was examined in BS-90 snails that were injected with FREP2 dsRNA and exposed to S. mansoni. Significant reduction of gene expression was observed for FREP2 and FREP6 (P < 0:01), but no reduction was observed in transcript abundance for the other four FREP genes (Fig. 8B). Knockdown of FREP6 is likely due to the high nucleotide identity (96%) between FREP2 and FREP6, which will be further discussed below. In conclusion, extensive cross-reactivity in RNAi was not observed.

4. Discussion

We chose three systems to investigate in this study: BS-90 snails—S. mansoni, M line snails—E. paraensei, and Bge cells—E. paraensei. BS-90 snails are resistant to S. mansoni whereas M line snails are susceptible. A previous study showed the expression of FREP2 in the BS-90 snails is upregulated after exposure to S. mansoni whereas M line snails have no response to schistosome infection, suggestive of a role for FREP2 in resistance [36]. Our study confirmed that FREP2 expression could be provoked in BS-90 snails after exposure to S. mansoni. Development of RNAi in the BS-90—S. mansoni combination provides a plausible way to evaluate the function of FREPs in defense against S. mansoni in resistant snails. Search for anti-schistosome molecules in the snail intermediate host is a long-term goal relevant to schistosomiasis control efforts. The M line—E. paraensei system has been studied in our lab as a model of host–parasite interactions, and FREPs were originally identified in M line snails infected with E. paraensei [30]. In addition to attempts to induce RNAi in vivo, we were interested in determining if, in principle, RNAi could be demonstrated in vitro, so we chose cells of the Bge cell line as potential targets for FREP2 knockdown. Here, we note that Bge cells were originally derived from embryonic snails so the exact cell lineage they represent is not well characterized. Although Bge cells have some properties consistent with those of hemocytes, it should not be assumed they are representative of hemocytes derived from juvenile or adult snails. Before proceeding with RNAi experiments, we first demonstrated an increase in FREP2 expression following exposure to E. paraensei in the latter two model systems. This is the first report that FREP2 expression can be upregulated in Bge cells following exposure to trematode larvae. Development of RNAi in a cell line will provide a potentially valuable alternative means to evaluate snail gene functions.

We then observed that injection of FREP2 dsRNA resulted in a 77–80% reduction of FREP2 transcript abundance in BS-90 and M line snails. Similar results were found for the myoglobin gene (68% reduction). Generally, knockdown of transcript abundance of 70% or more is considered to be an effective application of RNAi (Ambion). The efficiency of RNAi varies, depending on the species, tissue, or genes targeted. For example, knockdown of Toll, Dif and Drs genes in adult Drosophila were 26, 47 and 62%, respectively [15], and the knockdown of aminopeptidase (slapn) in Spodoptera litura larvae was up to 95% based on the intensity of RT-PCR bands [14].

The RNAi knockdown we achieved was transient. For both BS-90 and M line snails, significant reduction in FREP2 expression was not noted at 3 DPI, was achieved at both 4 and 6 DPI, and was gone by 10 DPI. Similar dynamics were noted for myoglobin. Goto et al. [15] reported that knockdown in fruitflies following direct injection of dsRNA lasted for at least 1 week [15]. In the planarian Girardia tigrina the RNAi effect on targeted transcript was apparent up to 3 weeks post-injection as determined by in situ hybridization [43]. In general, the mechanisms explaining longevity of the RNAi effect remain unknown. As the snails were exposed to infection 2 days following dsRNA injection, and sporocysts of S. mansoni are typically killed within 3 DPE in resistant snails [44,45], a significant level of knockdown would be achieved for much of the critical interval determining parasite success or failure. Thus even though transient, RNAi could still provide a unique opportunity to test the role of FREPs in defense against trematodes.

In the in vitro studies, the direct introduction of dsRNA into culture medium successfully knocked down targeted gene expression in snail cells. Clemens et al. [22] reported that dsRNA was capable of specifically blocking the production of targeted proteins in Drosophila cell lines when added directly to the culture media, without using a transfection reagent [22]. These results indicate that some cell lines effectively take up dsRNA. The transmembrane protein SID-1 has been found to transport dsRNA into Drosophila cells [46].

In addition to confirming our RNAi results, the Northern blot showed that a considerable amount of the injected dsRNA was still present in snails at 4 DPI. Our explanation is that this band represents dsRNA that was still present in the injected snails, either in intact or partially degraded form. It is possible that the dsRNA detected in the Northern blot was present in extracellular compartments, such as hemolymph because RNA was extracted from the whole body of snails.

It has been reported that off-target effects can be a potential problem for RNAi [47–49]. We first demonstrated that limited or no cross reactivity occurs between FREP2 and myoglobin, and then showed that with FREP subfamilies non-specific knockdown of expression was not observed except for FREP6. This may be explained by the fact that the available FREP6 sequence (ICR and FBG regions, a total of 625 bp) has 96% nucleotide identity with FREP2. In the same region, the identity between FREP2 and FREP4, the only other FREP with a single lgSF domain for which the complete gene sequences are known, is only 60% [32]. Although these results indicate that cross-reactivity is not extensive among FREP subfamilies, it does suggest the cross-reactivity may occur between two sequences with high nucleotide identity. This provides useful information for the design of future RNAi experiments to further minimize off-target effects for the purpose of knockdown of specific genes.

Many aspects of the RNAi effect in snails await further clarification. Our future studies will emphasize how to maintain the RNAi effect for longer periods of time. We also intend to examine how RNAi specifically affects gene expression in hemocytes, and how to develop an effective approach to examine the corresponding changes in protein abundance.

In summary, our data for the first time demonstrated that RNAi based on FREP2 and myoglobin genes can be achieved in two strains (BS-90 and M line) of the snail B. glabrata and its cell line (Bge cells). RNAi thus may be applied to assess snail gene functions, an approach that will become more useful once the B. glabrata genome, now being actively sequenced, has been obtained. RNAi will also be a useful tool to reveal the genes critical in mounting effective defense responses against medically important parasites such as S. mansoni that depend on their molluscan hosts for their larval development.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. L. A. Hertel for technical assistance with qPCR, Dr. C. M. Adema for valuable discussion and suggestions. Thanks are also given to Dr. T. P. Yoshino (University of Wisconsin) and our colleague Dr. T. S. Nowak for help with Bge cell culture. This work was supported by NIH Grant Number RR-1P20RR18754 from the International Development Award (IDeA) program of the National Center for Research Resources.

References

- 1.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherer LJ, Rossi JJ. Approaches for the sequence-specific knockdown of mRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1457–1465. doi: 10.1038/nbt915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell TN, Choy FYM. RNA interference: past, present and future. Curr Issue Mol Biol. 2005;7:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuwabara PE, Coulson A. RNAi: Prospects for a general technique for determining gene function. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:347–349. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbashir SM, Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusaba M. RNA interference in crop plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2004;15:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novina CD, Sharp PA. The RNAi revolution. Nature. 2004;430:161–164. doi: 10.1038/430161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holway AH, Hung C, Michael WM. Systematic RNA-interference-mediated identification of mus-101 modifier genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2005;169:1451–1460. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JK, Gabel HW, Kamath RS, Tewari M, Pasquinelli A, Rual JF, et al. Functional genomic analysis of RNA interference in C. elegans. Science. 2005;308:1164–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.1109267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle JP, Wu XJ, Shoemaker CB, Yoshino TP. Using RNA interference to manipulate endogenous gene expression in Schistosoma mansoni sporocysts. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skelly PJ, Da’dara A, Harn DA. Suppression of cathepsin B expression in Schistosoma mansoni by RNA interference. Intl J Parasitol. 2003;33:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quan GX, Kanda T, Tamura T. Induction of the white egg 3 mutant phenotype by injection of the double-stranded RNA of the silkworm white gene. Insect Mol Biol. 2002;11:217–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajagopal R, Sivakumar S, Agrawal N, Malhotra P, Bhatnagar RK. Silencing of midgut aminopeptidase N of Spodoptera litura by double-stranded RNA establishes its role as Bacillus thuringiensis toxin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46849–46851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goto A, Blandin S, Royet J, Reichhart JM, Levashina EA. Silencing of Toll pathway components by direct injection of double-stranded RNA into Drosophila adult flies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6619–6623. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dasgupta R, Perrimon N. Using RNAi to catch Drosophila genes in a web of interactions: insights into cancer research. Oncogene. 2004;23:8359–8365. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pili-Floury S, Leulier F, Takahashi K, Saigo K, Samain E, Ueda R, et al. In vivo RNA interference analysis reveals an unexpected role for GNBP1 in the defense against Gram-positive bacterial infection in Drosophila adults. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12848–12853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamang D, Tseng SM, Huang CY, Tsao IY, Chou SZ, Higgs S, et al. The use of a double subgenomic Sindbis virus expression system to study mosquito gene function: effects of antisense nucleotide number and duration of viral infection on gene silencing efficiency. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moita LF, Wang-Sattler R, Michel K, Zimmermann T, Blandin S, Levashina EA, Kafatos FC. In vivo identification of novel regulators and conserved pathways of phagocytosis in A. gambiae. Immunity. 2005;23:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amdam GV, Simoes ZLP, Guidugli KR, Norberg K, Omholt SW. Disruption of vitellogenin gene function in adult honeybees by intra-abdominal injection of double-stranded RNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2003;3:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aljamali MN, Bior AD, Sauer JR, Essenberg RC. RNA interference in ticks: a study using histamine binding protein dsRNA in the female tick Amblyomma americanum. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12:299–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemens JC, Worby CA, Simonson-Leff N, Muda M, Maehama T, Hemmings BA, Dixon JE. Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6499–6503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110149597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller P, Kuttenkeuler D, Gesellchen V, Zeidler MP, Boutros M. Identfication of JAK/STAT signaling components by genome-wide RNA interference. Nature. 2005;436:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nature03869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levashina EA, Moita LF, Blandin S, Vriend G, Lagueux M, Kafatos FC. Conserved role of a complement-like protein in phagocytosis revealed by dsRNA knockout in cultured cells of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Cell. 2001;104:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxwell MM, Pasinelli P, Kazantsev AG, Brown RH. RNA interference-mediated silencing of mutant superoxide dismutase rescues cyclosporin A-induced death in cultured neuroblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3178–3183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308726100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel U, Malik I, Ebert S, Bahr M, Kugler S. Long-term in vivo and in vitro AAV-2-mediated RNA interference in rat retinal ganglion cells and cultured primary neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2005;326:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korneev SA, Kemenes I, Straub V, Staras K, Korneeva EI, Kemenes G, Benjamin PR, O’Shea M. Suppression of nitric oxide (NO)-dependent behavior by double-stranded RNA-mediated silencing of a neuronal NO synthase gene. J Neurosci. 2002;22(11):RC227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-j0003.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JA, Kim HK, Kim KH, Han JH, Lee YS, Lim CS, et al. Overexpression of and RNA interference with the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein on long-term facilitation of Aplysia sensory to motor synapses. Learn Mem. 2001;8:220–226. doi: 10.1101/lm.40201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crompton DWT. How much human helminthiasis is there in the world. J Parasitol. 1999;85:397–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adema CM, Hertel LA, Miller RD, Loker ES. A family of fibrinogen-related proteins that precipitates parasite-derived molecules is produced by an invertebrate after infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8691–8696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S-M, Adema CM, Kepler TB, Loker ES. Diversification of Ig superfamily genes in an invertebrate. Science. 2004;305:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1088069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Léonard PM, Adema CM, Zhang S-M, Loker ES. Structure of two FREP genes that combine IgSF and fibrinogen domains, with comments on diversity of the FREP gene family in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Gene. 2001;269:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S-M, Leonard PM, Adema CM, Loker ES. Parasite-responsive IgSF members in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: characterization of novel gene with tandemly arranged IgSF domains and a fibrinogen domain. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:684–694. doi: 10.1007/s00251-001-0386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang S-M, Loker ES. The FREP gene family in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: additional members, and evidence consistent with alternative splicing and FREP retrosequences. Dev Comp Immunol. 2003;27:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(02)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang S-M, Loker ES. Representation of an immune responsive gene family encoding fibrinogen-related proteins in the freshwater mollusk Biomphalaria glabrata, an intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni. Gene. 2004;341:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hertel LA, Adema CM, Loker ES. Differential expression of FREP genes in two strains of Biomphalaria glabrata following exposure to the digenetic trematodes Schistosoma mansoni and Echinostoma paraensei. Dev Comp Immunol. 2005;29:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stibbs HH, Owczarzak A, Bayne CJ, DeWan P. Schistosome sporocyst-killing amoebae isolated from Biomphalaria glabrata. J Invertebr Pathol. 1979;33:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(79)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loker ES, Hertel LA. Alteration in Biomphalaria glabrata plasma induced by infection with the digenetic trematode Echinostoma paraensei. J Parasitol. 1987;73:503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen EL. A cell line from embryos of Biomphalaria glabrata (Pulmonata): establishment and characteristics. In: Maramorosch K, editor. Invertebrate tissue culture: research applications. New York: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coustau C, Ataev G, Jourdane J, Yoshino TP. Schistosoma japonicum: in vitro cultivation of miracidium to daughter sporocyst using a Biomphalaria glabrata embryonic cell line. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:77–87. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dewilde S, Winnepenninckx B, Arndt MH, Nascimento DG, Santoro MM, Knight M, et al. Characterization of the myoglobin and its coding gene of the mollusk Biomphalaria glabrata. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13583–13592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pineda D, Gonzalez J, Callaert P, Ikeo K, Gehring WJ, Salo E. Searching for the prototypic eye genetic network: sine oculis is essential for eye regeneration in planarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4525–4529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lie KJ, Jeong H, Heynemen D. Tissue reactions induced by Schistosoma mansoni in Biomphalaria glabrata. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1980;74:157–166. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1980.11687326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan JT, Richards CS, Joe LK, Heyneman D. Schistosoma mansoni, NIH-Sm-PR-2 strain, in non-susceptible Biomphalaria glabrata: protection by Echinostoma paraensei. Intl J Parasitol. 1981;11:481–484. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane proteins SID-1. Science. 2003;301:1545–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.1087117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oates AC, Bruce AE, Ho RK. Too much interference: injection of double-stranded RNA has nonspecific effects in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol. 2000;224:20–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson AL, Bartz SR, Schelter J, Kobayashi SV, Burchard J, Mao M, et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu S, Adema CM, Lane T. A computational study of off-target effects of RNA interference. Nucl Acids Res. 2005;33:1834–1847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]