SUMMARY

The parametric g-formula can be used to contrast the distribution of potential outcomes under arbitrary treatment regimes. Like g-estimation of structural nested models and inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models, the parametric g-formula can appropriately adjust for measured time-varying confounders that are affected by prior treatment. However, there have been few implementations of the parametric g-formula to date. Here, we apply the parametric g-formula to assess the impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS or death in two US-based HIV cohorts including 1,498 participants. These participants contributed approximately 7,300 person-years of follow-up of which 49% was exposed to HAART and 382 events occurred; 259 participants were censored due to drop out. Using the parametric g-formula, we estimated that antiretroviral therapy substantially reduces the hazard of AIDS or death (HR=0.55; 95% confidence limits [CL]: 0.42, 0.71). This estimate was similar to one previously reported using a marginal structural model 0.54 (95% CL: 0.38, 0.78). The 6.5-year difference in risk of AIDS or death was 13% (95% CL: 8%, 18%). Results were robust to assumptions about temporal ordering, and extent of history modeled, for time-varying covariates. The parametric g-formula is a viable alternative to inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models and g-estimation of structural nested models for the analysis of complex longitudinal data.

Keywords: Cohort study, Confounding, g-formula, HIV/AIDS, Monte Carlo methods

1. INTRODUCTION

The g-formula[1], g-estimation of structural nested models[2], and inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models[3] (collectively known as g-methods, where g stands for “generalized”) can be used to estimate causal effects of time-varying treatments while appropriately adjusting for time-varying confounders affected by prior treatment without introducing collider-stratification bias, and can in addition be used to estimate marginal (as opposed to conditional) effect estimates to avoid the problems associated with non-collapsible effect measures [4, 5].

G-estimation of structural nested models and inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models are semiparametric methods that can handle the high dimensional data encountered in biomedical research, and therefore have been frequently implemented[6–11]. In its original form, the g-formula is a nonparametric method that does not rely on modeling, and therefore its application is limited to low dimensional settings[12]. An alternative form of the g-formula, known as the parametric g-formula[13], relies more heavily on modeling and can therefore be used in high dimensional problems. There are few published examples of the g-formula dealing with either time-fixed [13–16] or time-varying treatments [14, 17, 18].

Here we describe a novel application of the parametric g-formula to estimate the effect of time-varying highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) on the cumulative incidence of AIDS or death among HIV-infected participants in two prospective U.S. studies. We compare the parametric g-formula estimates with those previously obtained from inverse probability weighting [19] and g-estimation [20]. In section 2 we describe the example data for analysis. In section 3 we describe the g-formula. In section 4 we describe parametric estimation of the g-formula. In section 5 we present results. We close in section 6 with a discussion.

2. THE MULTICENTER AIDS COHORT STUDY AND WOMEN’S INTERAGENCY HIV STUDY

This analysis used information from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS)[21] and the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) [22], which have been described in detail elsewhere. Briefly, the MACS enrolled 6,972 homosexual and bisexual men in Baltimore, Chicago, Pittsburgh and Los Angeles beginning in 1984, whereas the WIHS enrolled 3,772 women in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington DC beginning in 1994. Every six months, participants in both studies completed an extensive interviewer-administered questionnaire regarding antiretroviral therapy use and provided a blood sample for the determination of CD4 cell count and HIV viral load. Institutional review boards approved all protocols and informed consent forms, which were completed by study participants in both cohorts.

Our analysis is restricted to 1,498 participants who were HIV-positive, free of clinical AIDS, and had not initiated HAART at a study visit by September 1995, just prior to the availability of HAART in the United States. Follow-up began between September 1995 and December 1996. Participants were followed until April 2002, a diagnosis of an AIDS-defining illness [23], death, or loss to follow-up, whichever occurred first. Deaths were ascertained using death certificate abstractions upon notification and National Death Index searches, as described previously [19]. Loss to follow-up was defined as missing two consecutive study visits. The maximum follow-up was approximately 6.5 years (13 semiannual visits).

The definition of HAART was based on recommendations from the Department of Health and Human Services and Kaiser Panel guidelines.[24] As in previous analyses, we assumed that once participants reported HAART initiation, they remained on HAART for the duration of follow-up, which correctly classified 94% of the observed person-time after initiation.[19, 25]

We assumed that, at each study visit, those who did and did not initiate HAART were exchangeable conditional on the variables sex, race, age, viral load, and CD4 cell count measured at baseline; as well as on a time-varying indicator of detectable viral load (1 if >400 copies/ml, 0 otherwise) and time-varying CD4 cell count. Further adjustment for baseline and time-varying HIV symptoms, non-HAART antiretroviral therapy, prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and days since the prior visit did not materially affect our estimate, so we did not adjust for those variables here. We carried-forward missing values of CD4 cell count and viral load, but examined an alternative approach to missing data in a sensitivity analysis.

3. THE G-FORMULA

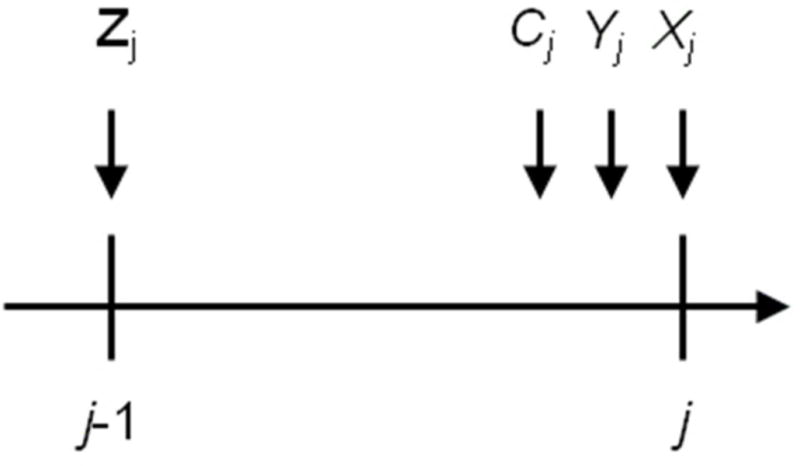

We begin with a formal description of the observed data. Let uppercase letters represent random variables and lowercase letters represent realizations. Let i = 1, 2, …, N denote subject, and j = 0, 1, …, J denote visit with N = 1498 and J = 12. For participant i, let Zij be the vector of confounders measured at visit j−1 (see previous section for list). Let Xij = 1 indicate treatment with HAART by visit j. Let Cij+1 = 1 indicate censoring due to drop-out by visit j+1. Let Yij+1 = 1 indicate a diagnosis of AIDS or death by visit j+1. By design, Xi−1 = 0 (all subjects are treatment-naïve at baseline) and Ci0 = Yi0 = 0 (all subjects are at risk of AIDS or death at baseline). By definition, if Yij = 1 then Yij+1 = 1 and if Cij = 1 then Cij+1 = 1. By convention, Zi−1 = 0. For each visit j, we assume the order (Zij, Cij, Yij, Xij) as represented in Figure 1. The history of a variable is denoted with an overbar. For example ; note that therefore includes baseline covariates Zi0. Below, we sometimes suppress the subscript i to simplify notation.

FIGURE 1.

Time-ordering of variables. For each visit j, we assume the order (Zij, Cij, Yij, Xij).

The cumulative incidence of AIDS or death in the observed data by visit j+1 can be written as follows:

where Pr(A=a | B=b) is the conditional probability of A=a given B=b, and f(A=a | B=b) is the conditional density of A given B evaluated at the values A=a and B=b.

The g-formula can be used to consistently estimate the cumulative incidence of AIDS or death under a hypothetical treatment intervention [26]. Like for all methods based on covariate adjustment, the validity of g-formula estimates requires the following identifying conditions: exchangeability (that is, no uncontrolled confounding or uncontrolled selection bias) conditional on the measured covariates [27], positivity conditional on the measured covariates [28], and consistency [29]. Robins and Hernán [31] provide a formal description of these conditions in longitudinal settings.

Here we consider interventions of the form “set the exposure history and allow no censoring by loss to follow-up”. The following g-formula can be used to consistently estimate the cumulative incidence of AIDS or death by visit j+1 under an intervention of this form [26]

In this analysis, we are specifically interested in evaluating the g-formula for or “always treat” and or “never treat.” Note that ensuring no loss to follow-u is a component of both interventions.

4. PARAMETRIC ESTIMATION OF THE G-FORMULA

In low-dimensional data (in particular, when there are relatively few, non-continuous covariates in the covariate history ) one can in theory calculate the g-formula directly. In high-dimensional data, parametric models are required to estimate each factor of each product in the sum, and a Monte Carlo simulation is required to approximate the sum because directly computing the sum becomes infeasible.

We implemented the following algorithm to estimate the g-formula for and for each j = 0, …, 12:

-

Parametric modeling. Using the 1,498 subjects from the original sample, fit parametric models for:

The density of covariates measured in visit j−1 (Zj) conditional on past covariate history through j−2, following the intervention through j−1, and surviving and remaining uncensored to visit j−1 (for j > 0 only).

The probability of AIDS or death in visit j+1 (Yj+1) conditional on past covariate history through j−1, following the intervention through m, surviving to visit j and remaining uncensored to visit j+1.

-

Monte Carlo simulation: Create two data sets of 74,900 (that is, 50 times the original sample size of 1,498) replicates, each of them with a combination of values of baseline covariates randomly chosen from the combinations found in the original 1,498 subjects, first for and second for . For each data set do the following:

Assign to each replicate the value of the corresponding subject’s covariates at j=0.

For each replicate, assign covariate values Zm under by drawing from the conditional densities estimated in step 1a evaluated at previously assigned values of and the value of treatment .

For each replicate, assign the outcome value Yj+1 under by drawing from the conditional probability estimated in step 1b evaluated at the previously assigned values of and the value of treatment .

If Yj+1 = 0, continue assigning covariate and outcome values for that replicate. If Yj+1 = 1, exit for that replicate.

This algorithm differs from the one used by Taubman et al.[17] in that Taubman et al. did not assign individual outcome values (1 or 0) but rather used the estimated conditional probability of the outcome for the calculations. The approach described here allows one to estimate the average hazard ratio from a Cox model as described below and in Toh et al.[32]

Previous analysis used inverse probability weighting[19] to estimate the hazard ratio for “always treat” vs. “never treat” from a marginal structural Cox model. For comparison purposes, we estimated the same hazard ratio by fitting the pooled logistic regression model

to the simulated dataset where x is an indicator (1: always treated, 0: never treated), α0(j) is a visit specific intercept which we modeled using indicator variables. The model coefficients are estimated in the dataset obtained by pooling the two simulated data sets obtained after Step 2 of the above algorithm.

As noted above the point estimates were obtained from a single sample of 50 × 1,498. Results were essentially the same at increased sample sizes (e.g., 100 × 1,498). Variance estimates for the hazard ratio are obtained through nonparametric bootstrapping of the above procedure with 500 samples; the standard error for the point estimate is estimated as the standard deviation of the resultant 500 point estimates.

The g-formula can also be used to estimates the absolute risk under each intervention. For each of the two simulated datasets, the proportion of replicates with Yj+1 = 1 estimated the risk of failure by j+1 under the intervention .

The “natural course ” scenario

The procedure described above does not require fitting models for treatment and censoring by loss to follow-up at each time. However, if one is willing to also model the conditional probability of receiving treatment, then one can use the g-formula algorithm described above to estimate the probability of AIDS or death that would have been observed under no intervention on treatment. This “natural course” risk is expected to be similar to the observed risk if all models involved in the procedure are correctly specified. Modeling assumptions used for treatment and censoring for this “natural course” estimator are also detailed below.

Modeling assumptions

Here we describe the parametric assumptions we made in step 1 of the algorithm described above, as well as those for the treatment and censoring processes required for the natural course scenario.

Each line of a our data set corresponds to visit j of a subject and consists of (j, zj, zj−1, zj−2, z0, xj, xj−1, xj−2, cj+1, yj+1). The first line for each subject corresponds to j = 0, and the last one to the time j immediately before the subject failed or was censored, or reached the administrative end of follow-up (j=13), whichever occurred earlier. In our analysis, Zj for j>0 consists of continuous CD4 count in cells/mm3(CD4j) and an indicator for detectable viral load (VLj; cut point at 400 copies/ml) measured at visit j−1. Z0 consists of the variables CD40, VL0(both specified as three category variables, see Table 1), RACE (Caucasian, other) SEX, and AGE (in years). We made the following modeling assumptions with coefficient vectors estimated using standard SAS procedures for logistic and linear regression.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1,498 HIV-positive US Men and Women Naïve for Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy at Study Entry, 1995.

| Men (n=506) | Women (n=992) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Agea | 42 | (37, 46) | 37 | (31, 42) |

| Caucasian race | 398 | 78.7 | 163 | 16.4 |

| CD4 count (cells/ml): | ||||

| <200 | 70 | 13.8 | 188 | 18.9 |

| 200–350 | 129 | 25.5 | 244 | 24.6 |

| >350 | 307 | 60.7 | 560 | 56.5 |

| CD4 count (cells/ml)a | 418 | (265, 585) | 380 | (222, 567) |

| HIV viral load (copies/ml): | ||||

| ≤ 400 | 73 | 14.4 | 349 | 35.2 |

| 401–10,000 | 124 | 24.5 | 148 | 14.9 |

| >10,000 | 309 | 61.1 | 495 | 49.9 |

| log10 HIV viral load (copies/ml)a,b | 4.4 | (3.9, 4.9) | 4.6 | (4.1, 5.0) |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Median (quartiles)

Among persons with detectable levels (i.e., > 400 copies/ml), n=433 men and n=643 women.

For j = 0, …, J, we assumed

where expit(•) = exp(•)/[1+exp(•)] is the anti-logit function. An analogous model was assumed for .

For treatment, we assumed (an ‘intent to treat’ assumption consistent with observed data and previous analyses [19, 20]) and

The censoring model was similar to the treatment model.

Last, for j > 0 we assumed

where

where ε is distributed normal (0, σ2), and

.

5. RESULTS

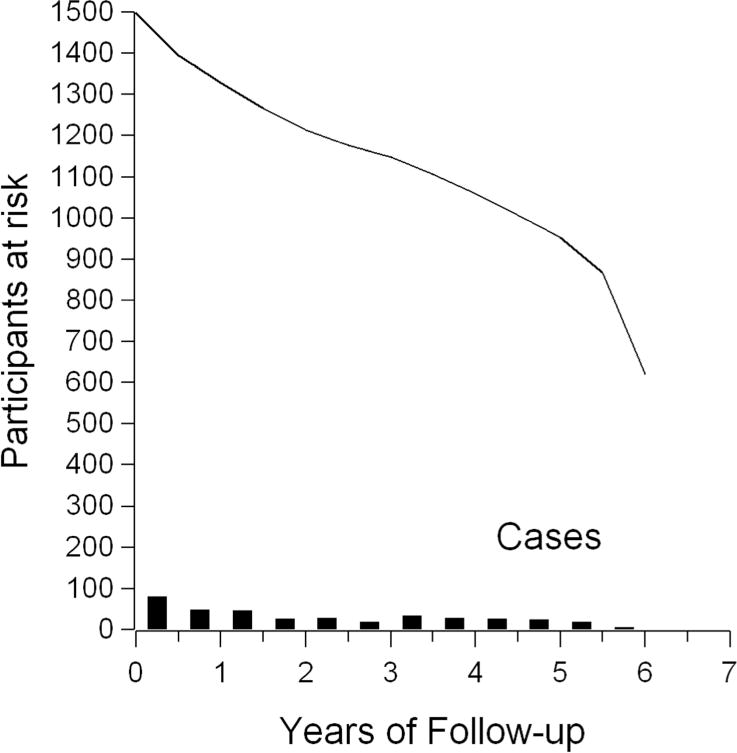

Table 1 shows characteristics at study entry for the 1,498 participants. Median age at study entry was 39 years; 66% were female and 37% were Caucasian. About 17% entered study with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3; while 58% had CD4 counts greater than 350 cells/mm3; 28% entered study with plasma HIV RNA viral load less than or equal to 400 copies/ml. During follow-up, 382 incident cases of clinical AIDS and deaths occurred. 259 (17%) were lost to follow-up, and 857 (57%) were administratively censored. Figure 2 illustrates the number of participants at risk over follow up, as well as when endpoints occurred.

FIGURE 2.

Number at risk, and number of endpoints, by length of study follow up for 1,498 participants.

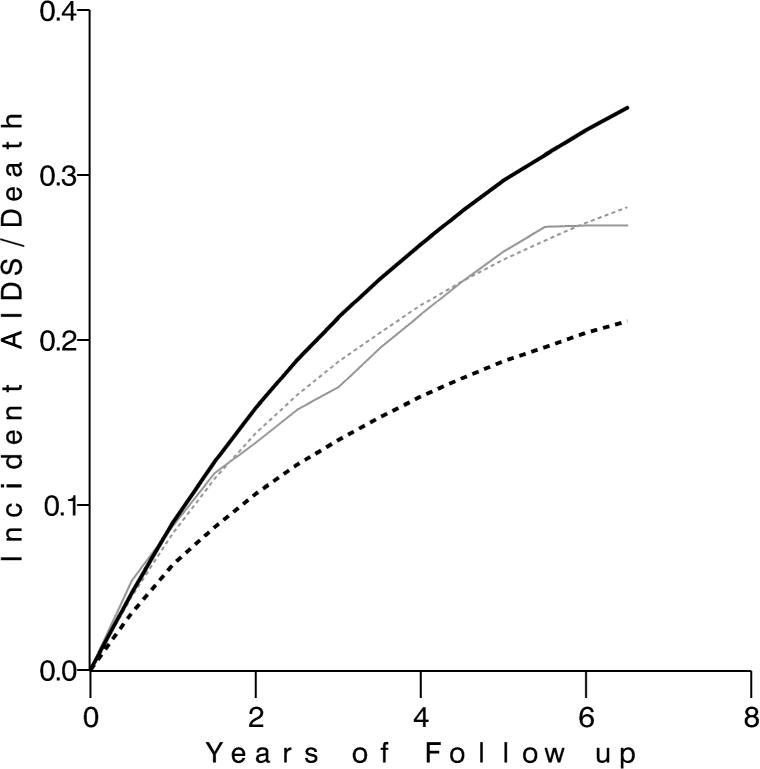

In Table 2, we show characteristics for the observed data and the data simulated by the parametric g-formula under the “natural course”, the “never treat”, and the “always treat” scenarios. The “natural course” scenario yields results similar to the observed data, as desired. Specifically, the amount of total and exposed person-time, number of total and exposed events, and values of time-varying covariates are similar in the observed data and the natural course scenario. Under the never treat scenario, there is less person-time, more numerous events, lower final CD4 cell count and higher final viral load than in the always treat scenario. Similarly, Figure 3 shows that the risk of AIDS or death is similar in the observed data and natural course scenario, substantially higher in the never treat scenario, and lower in the always treat scenario.

Table 2.

Characteristics of observed data and four simulation scenarios described in text. Values are derived from a single simulation of sample size 1,498 × 50, then normalized by 50 to represent the mean from a single run of the model.

| Exposure scenario | Observed | Natural Course | Never | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1,498 | 1,498 | 1, 498 | 1, 498 |

| Person-visits, n | 14,641 | 14,651* | 15,682‡ | 17,021‡ |

| Exposed person-visits, % | 48.8 | 47.6 | 0. | 100. |

| Events, n | 382 | 395 | 511 | 317 |

| Exposed events, % | 37.7 | 39.2 | 0. | 100. |

| Final CD4 cells/ml3, mean | 462 | 459 | 376 | 546 |

| Final detectable viral load, % | 56.8 | 57.8 | 79.3 | 42.0 |

Detectable viral loads are those >400 copies/ml.

In the natural course scenario without censoring, there were 16,210 person-visits and results generally fell in between the never and always scenarios.

There was no drop-out in the Never and Always scenarios.

FIGURE 3.

Absolute risk of AIDS or death over follow-up in the never treated (solid black), observed (solid gray), natural course (dotted gray), and always treated (dotted black) g-formula scenarios.

Table 3 shows estimates of the hazard ratios of AIDS or death for always treat versus never treat with HAART, as well as 95% confidence limits. The hazard ratio (95% CL) was 0.94 (0.74, 1.19) from an unadjusted model, 0.66 (0.50, 0.87) from a model adjusting for time-fixed covariates, and 0.56 (0.42, 0.75) from a model that further adjusted for time-varying covariates via inverse probability weights. These estimates are consistent with a prior report from these data[19], as well as with other existing randomized [33, 34] and observational [7] evidence. The AIDS or death hazard ratio from the parametric g-formula was 0.55 (95% CL: 0.42, 0.71).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence limits (CL) for always versus never treating with combination antiretroviral therapy.

| Cox Models | Hazard Ratio | 95% CL | Point estimate (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No covariates a | 0.94 | 0.74, 1.19 | −0.066 (0.123) |

| Baseline covariates, unweighted | 0.66 | 0.50, 0.87 | −0.414 (0.140) |

| Baseline and time-varying covariates, unweighted a | 0.75 | 0.58, 0.96 | −0.294 (0.129) |

| Baseline covariates, weighted a | 0.56 | 0.42, 0.75 | −0.575 (0.147) |

| Parametric g-formula b | 0.55 | 0.42, 0.71 | −0.606 (0.133) |

Baseline covariates were age, sex, weight, visit, and (baseline) viral load and CD4 count. Time-varying covariates were viral load and CD4 count.

Results from Cole et al. AJE 2003 were: 0.98 (95% CL: 0.76, 1.26), 0.81 (95% CL: 0.61, 1.07), and 0.54 (95% CL: 0.38, 0.78), respectively.

Adjusted for all baseline and time-varying covariates.

The g-formula also yields estimates of absolute risk. Under the always treated scenario approximately 21% of participants incurred AIDS or died by approximately 6.5 years of follow up. Under the never treated scenario, approximately 34% of participants incurred AIDS or died after the same length of follow up. The 6.5-year risk difference was 12.8% (95% CL: 7.7%, 18.1%) (Figure 3).

In addition to the natural course scenario described above, we performed several analyses to explore the sensitivity of the results from the parametric g-formula. We reversed the order of the parametric models for time-varying viral load and CD4 cell count in the algorithm; we used a single prior value of viral load, CD4 cell count, and HAART, rather than two prior values for each, as model covariates; and we adjusted for time gaps between visits (median time 6 months, interquartile range 5.4, 6.4 months). The estimates did not materially change. In addition we used the SAS macro originally published by Taubman et al. [17] to repeat the main analysis; we found a 6.5 year risk difference of 12.6% (compare to 12.8% above).

In a last sensitivity analysis, we set time-varying CD4 cell count and viral load to missing when the visit was missed, forgoing carry-forward for these observations. This had the effect of reducing misclassification of CD4 cell count and viral load, while at the same time reducing sample size. This analysis yielded a hazard ratio of 0.60 (95% CL: 0.44, 0.81).

6. DISCUSSION

In the presence of time-varying confounders affected by prior treatment [1], the use of traditional multivariable regression techniques may result in biased estimates of treatment effects. In contrast, the parametric g-formula, inverse probability weighting and g-estimation can appropriately adjust for measured time-varying confounders [26]. Here we have demonstrated that the parametric g-formula provide comparable results to inverse probability weighting. Using inverse probability weighting, we obtained an estimate of the hazard ratio for the effect of HAART on time to AIDS or death of 0.56 (95% CL 0.42, 0.75). Our parametric g-formula estimate was 0.55 (95% CL 0.42, 0.71). In addition, using the latter method, we were able to obtain estimates of risk difference.

Our inverse probability weighting and parametric g-formula results were similar to those found in earlier analyses of these data. In 2003, Cole et al. reported a hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% confidence limits [CL], 0.38, 0.78) comparing always treat to never treat with HAART on time to AIDS or death using inverse probability weighting of a marginal structural model[19]. In 2005, Hernán et al. reported that continuous HAART increases participants’ AIDS-free survival time by a factor of 2.51 (95% CL 1.72, 3.29) compared to no HAART estimating a structural nested accelerated failure time model; the associated hazard ratio was 0.42, a qualitatively similar result[20].

To date there have been relatively few implementations of the parametric g-formula. In 2009, Taubman et al. published an example along with a SAS macro for implementation of the parametric g-formula[17]. Our implementation, programmed independently, yields essentially identical results. As noted above, this approach differs from that of Taubman et al.[17] in that we simulate the value of the outcome for each individual at each time, rather than predicting only the average of the individual outcomes. While this gives us the flexibility to estimate hazard ratios, it also makes this implementation more computationally intensive than alternative approaches.

All g-methods (parametric g-formula, g-estimation of structural nested models and inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models) can appropriately adjust for measured time-varying confounding affected by prior treatment. Each of these methods, however, makes different parametric assumptions. For the types of interventions considered here, while the parametric g-formula requires a model for every time-varying confounder, inverse probability weighting and g-estimation require a dose-response structural model and models for treatment and censoring [35]. We therefore recommend that the parametric g-formula is routinely used along with these other methods. Similar estimates arising from methods that rely on different parametric assumptions is reassuring, as in the example described in this paper. Moreover, different estimates may help identify particular parametric assumptions to which the estimates are especially sensitive. In addition, while inverse probability weights may become highly unstable with practical violations of the positivity assumption, the g-formula is much less susceptible to this instability.

Several limitations of this analysis should be noted. First, the most natural starting point for follow-up of HIV patients may be date of HIV seroconversion, a date which was unknown in these data. Here we followed the approach of most randomized trials, which enroll prevalently-infected HIV-infected patients. Second, as with any analysis of observational data, the validity of our results requires that all confounders are correctly measured and included in the analysis. Here, we believe these assumptions to be reasonable based on current knowledge about the factors involved in the decision to treat HIV-infected patients. In addition, our findings are similar to those from similar comparisons in randomized trials [33, 34].

Compared with g-estimation and inverse probability weighting, the parametric g-formula can be more easily used to evaluate the causal effect of complex interventions [17]. In particular, dynamic treatment regimes [36] and joint interventions on multiple factors can be explored naturally with this method. Additional examples of the parametric g-formula, in concert with semiparametric analyses like marginal structural models are needed; future work might be especially fruitful in focusing on examples where results from the g-formula differ from semiparametric results.

In conclusion, the parametric g-formula is a powerful tool for causal inference in both static and dynamic treatment comparison settings, and should receive wider consideration for use alongside inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models and g-estimation of structural nested models.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Daniel Westreich was supported by NIH grants K99-HD-063961 and 5 T32 AI 07001–32. Dr. Stephen R. Cole was partially supported by NIH grants R01-AA-017594 and P30-AI-50410. Drs. Jessica Young and Miguel A. Hernán were supported by NIH grant R01-AI-073127-01A2 . The authors would like to thank Dr. James Robins for expert advice.

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington, DC, Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) with centers (Principal Investigators) at The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Joseph B. Margolick, Lisa P. Jacobson), Howard Brown Health Center, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and Cook County Bureau of Health Services (John P. Phair, Steven M. Wolinsky), University of California, Los Angeles (Roger Detels), and University of Pittsburgh (Charles R. Rinaldo). The MACS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with additional supplemental funding from the National Cancer Institute. UO1-AI-35042, 5-MO1-RR-00052 (GCRC), UO1-AI-35043, UO1-AI-35039, UO1-AI-35040, UO1-AI-35041. Website located at http://www.statepi.jhsph.edu/macs/macs.html.

References

- 1.Robins JM. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with sustained exposure periods – application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Mathe Model. 1986;7:1393–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robins JM. Structural nested failure time models. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 4372–4389. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernán MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615–625. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole SR, Platt RW, Schisterman EF, Chu H, Westreich D, Richardson D, Poole C. Illustrating bias due to conditioning on a collider. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):417–420. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodnar LM, Davidian M, Siega-Riz AM, Tsiatis AA. Marginal structural models for analyzing causal effects of time-dependent treatments: an application in perinatal epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):926–934. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Ledergerber B, Tilling K, Weber R, Sendi P, Rickenbach M, Robins JM, Egger M. Long-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366(9483):378–384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole SR, Hernán MA, Anastos K, Jamieson BD, Robins JM. Determining the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA viral load using a marginal structural left-censored mean model. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(2):219–227. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen ML, van der Laan MJ, Napravnik S, Eron JJ, Moore RD, Deeks SG. Long-term consequences of the delay between virologic failure of highly active antiretroviral therapy and regimen modification. Aids. 2008;22(16):2097–2106. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830f97e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Gatell H, Cole SR, Margolick JB, Witt MD, Martinson J, Phair JP, Jacobson LP. Effect of tuberculosis on the survival of HIV-infected men in a country with low tuberculosis incidence. Aids. 2008;22(14):1869–1873. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almirall D, Ten Have T, Murphy SA. Structural Nested Mean Models for Assessing Time-Varying Effect Moderation. Biometrics. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robins J. The control of confounding by intermediate variables. Stat Med. 1989;8(6):679–701. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robins J. A graphical approach to the identification and estimation of causal parameters in mortality studies with sustained exposure periods. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(Suppl 2):139S–161S. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9681(87)80018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robins J, Hernán M, Siebert U. Effects of multiple interventions. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray C, editors. Global and Regional Burden of Diseases Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. vol 2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Wal WM, Prins M, Lumbreras B, Geskus RB. A simple G-computation algorithm to quantify the causal effect of a secondary illness on the progression of a chronic disease. Stat Med. 2009;28(18):2325–2337. doi: 10.1002/sim.3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snowden JM, Rose S, Mortimer KM. Implementation of G-computation on a simulated data set: demonstration of a causal inference technique. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(7):731–738. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taubman SL, Robins JM, Mittleman MA, Hernan MA. Intervening on risk factors for coronary heart disease: an application of the parametric g-formula. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1599–1611. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young J, Cain L, Robins J, O’Reilly E, Hernán M. Comparative effectiveness of dynamic treatment regimes: an application of the parametric g-formula. Statistics in Biosciences. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12561-011-9040-7. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole SR, Hernán MA, Robins JM, Anastos K, Chmiel J, Detels R, Ervin C, Feldman J, Greenblatt R, Kingsley L, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on time to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or death using marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(7):687–694. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernán MA, Cole SR, Margolick J, Cohen M, Robins JM. Structural accelerated failure time models for survival analysis in studies with time-varying treatments. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(7):477–491. doi: 10.1002/pds.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR., Jr The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(2):310–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, Young M, Greenblatt R, Sacks H, Feldman J. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(RR-17):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection . Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services and Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. AIDSinfo [formerly HIV/AIDS Treatment Information Service], National Institutes of Health; 2000. ( http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole SR, Hernán MA, Margolick JB, Cohen MH, Robins JM. Marginal structural models for estimating the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy initiation on CD4 cell count. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(5):471–478. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robins JM, Hernán MA. Estimation of the causal effects of time-varying exposures. In: Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, editors. Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 2008. pp. 553–599. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Estimating causal effects from epidemiological data. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(7):578–586. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westreich D, Cole SR. Invited commentary: positivity in practice. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):674–677. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp436. discussion 678–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole SR, Frangakis CE. The consistency statement in causal inference: a definition or an assumption? Epidemiology. 2009;20(1):3–5. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818ef366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudgens MG, Halloran ME. Toward Causal Inference With Interference. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(482):832–842. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robins J, Hernán M. Estimation of the causal effects of time-varying exposures. In: Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, editors. Longitudinal Data Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toh S, Hernandez-Diaz S, Logan R, Robins JM, Hernan MA. Estimating absolute risks in the presence of nonadherence: an application to a follow-up study with baseline randomization. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):528–539. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181df1b69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron DW, Heath-Chiozzi M, Danner S, Cohen C, Kravcik S, Maurath C, Sun E, Henry D, Rode R, Potthoff A, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of ritonavir in advanced HIV-1 disease. The Advanced HIV Disease Ritonavir Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351(9102):543–549. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, Grimes JM, Demeter LM, Currier JS, Eron JJ, Jr, Feinberg JE, Balfour HH, Jr, Deyton LR, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernán MA, Lanoy E, Costagliola D, Robins JM. Comparison of dynamic treatment regimes via inverse probability weighting. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98(3):237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]