Abstract

It is generally held that the retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor functions in multiple tissues to protect against tumor development. However, preclinical studies and analysis of tumor samples of early disease did not support an important role of RB loss in the origin of prostate cancer. By contrast, recent observations in the clinical setting and subsequent modeling of RB function indicate that the tumor suppressor has specialized roles in controlling androgen receptor expression in prostate cancer, and primarily functions to prevent progression to the castration-resistant stage of disease. Furthermore, preclinical models have now shown that loss of RB expression or functional activity decreases the effectiveness of hormone therapy, yet seems to increase sensitivity to a subset of chemotherapeutic agents. Here, the current state of knowledge regarding the implications of RB loss for prostate cancer progression will be reviewed, and potential opportunities for developing RB as a metric to predict therapeutic response will be considered.

Introduction

Prostate cancer remains the most frequently diagnosed malignancy in males in the USA and the second-most frequently diagnosed worldwide. Although the majority of men afflicted by this disease will die of competing causes, prostate cancer still results in substantial morbidity and takes the lives of over 30,000 men yearly in the USA and over 250,000 worldwide.1,2 As castration (achieved surgically or pharmacologically) is an effective way to control the disease,3 the vast majority of men who die of prostate cancer have castration-resistant disease. It is imperative, therefore, that the mechanisms involved in the development of castration resistance be understood, in order to arrive at effective therapies for the lethal prostate cancers. Multiple molecular abnormalities, including Nkx3.1 and PTEN downregulation, GSTP1 promoter methylation, MYC upregulation, and ETS transcription factor rearrangements, have been described in prostate cancer and been held responsible for its pathogenesis, resistance and adaptation to existing therapies.4–7 While these studies have contributed immensely to our understanding of prostate cancer biology, none have proven to have the predictive value that the practicing clinician requires for incorporation into the management of patients afflicted by this malignancy. Herein, we review the literature that places the retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor at the center of pathways implicated in prostate cancer progression, and suggests that therapy decisions might one day be made based on knowledge of the proficiency of the RB pathway.

Loss of RB and castration resistance

The demonstration of RB deficiency in the clinical setting was initially complicated by the large size of the gene8 and the multiple levels at which the function of the 928-amino-acid protein can be disrupted.9,10 Bookstein et al.11 first reported a deletion at exon 21 of the RB1 gene in DU145 prostate cancer cells resulting in a nonfunctional RB protein, and then demonstrated that a deletion of nucleotides 29–131 abrogated the promoter activity of RB1 in one of seven prostate cancer tumors (interestingly, one with a mixed small cell and adenocarcinoma morphology). Although additional point mutations and base deletions were subsequently described,12 a mutational hotspot of the RB1 gene in prostate cancer could not be found.13,14 A number of studies then reported allelic loss of the RB1 gene in 27–67% of prostate tumors, as well as decreased levels of transcript and protein immunostaining.15–21

However, it is imperative to note that retention of immunohistochemical positivity does not equate to retention of RB function, as its tumor suppressor activity can be dismantled via alternative means.9,10 It has been established in other tumor types that, despite retention of immunohistochemical positivity, RB function can be inactivated through upstream signaling pathways that alter post-translational modification of the protein through loss of cofactors that are required for RB function and/or through mutations that result in production of nonfunctional RB protein.9,10,22 Nonetheless, these studies did show an increase in the frequency of RB1 alterations associated with disease stage and, more remarkably, with exposure to androgen ablation therapies and disease progression.

In order to obtain a more rigorous assessment of RB activation state and to truly discern RB status, even in tumors scoring positive for the protein, gene expression “signatures” were developed using models of genetic RB deletion.23–26 These signatures have been extensively described and reviewed, and have been validated across multiple model systems to accurately reflect RB status. Notably, the signature overlaps with—but is distinct from—proliferative signatures, further underscoring the impact of RB on cancer cell phenotypes. Application of this gene signature in the context of prostate cancer further reinforced two concepts: first, despite its relatively low frequency in primary disease, a high representation of the RB loss signature is associated with reduced recurrence-free survival after prostatectomy;21,23–26 and second, RB function is ablated at high frequency in advanced, castration-resistant tumors.21 Overall, these observations indicate that loss of the RB tumor suppressor primarily occurs during tumor progression, particularly in the transition to castration resistance.

Role of RB in prostate tumorigenesis

The observation that RB loss is infrequent in primary disease is consistent with the results of preclinical studies investigating the role of RB in prostate tumorigenesis. The RB tumor suppressor is generally thought to protect against tumor development in other tissues through the capability of the protein to suppress expression of genes associated with cell cycle progression, DNA replication, and apoptosis; however, preclinical studies evaluating the functional consequences of RB loss in human prostate cancer cells surprisingly showed that this event does not confer a proliferative advantage in vitro or in vivo.11,21,27 Reconstitution of RB can attenuate prostate tumorigenicity in human tumor xenograft studies,28,29 although conditional deletion of Rb1 in the mouse prostate epithelium produces epithelial hyperplasia without atypia.30 Similar results were observed using murine epithelia in tissue recombination models, wherein Rb1 deletion yielded little discernible effect on prostatic histodifferentiation, but mild epithelial hyperplasia was observed.31,32 Interestingly, in a subset of these tissue recombination models, the addition of exogenous steroid hormones (testosterone plus estradiol) did lead to Rb1-loss-dependent prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and invasive carcinoma, supporting the existence of cooperation between RB function and the androgen receptor (AR) axis. In unchallenged models, however, even when RB1 is inactivated together with related proteins (p107 and p130), only PIN lesions ensue.33

In the context of genetically engineered mouse models, it takes conditional inactivation of both p53 and RB in the murine prostate epithelium to produce metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate that shares similarities with the human disease.34 While these findings reveal a link between RB loss and advanced disease in mouse models of prostate cancer, it is important to keep in mind the differences between mouse and human prostate: the murine prostate is anatomically distinct from that of humans, with functional zones (in humans) versus lobes (in mice), and obviously carries a distinct micro-environment. In addition, the murine prostate does not produce PSA, a clinical marker of disease development and progression that figures prominently in assessing resurgent AR activity and recurrent tumor formation.35 Further investigation is needed to identify and develop model systems of RB loss that faithfully recapitulate events observed in human disease.

RB loss and hormone therapy failure

Of greater potential significance for the practicing clinician is the implication of RB in the response to androgen and androgen withdrawal in prostate cancer. Initial studies showed that, in human prostate cancer cells, androgen signaling downregulates RB activity (via phosphorylation), thus facilitating cell cycle progression. By contrast, androgen withdrawal bolsters RB function, thereby promoting G1 arrest.36,37 Follow-up studies unexpectedly showed that the proliferation of RB-deficient prostate cancer cells was more resistant to androgen depletion and/or the AR antagonist bicalutamide than their isogenic RB-proficient counterparts, both in vitro and in vivo.21,27 Consistent with these observations, activation of E2F1, a transcription factor that is activated upon RB loss, promotes resistance to androgen deprivation in human prostate cancer cells.38

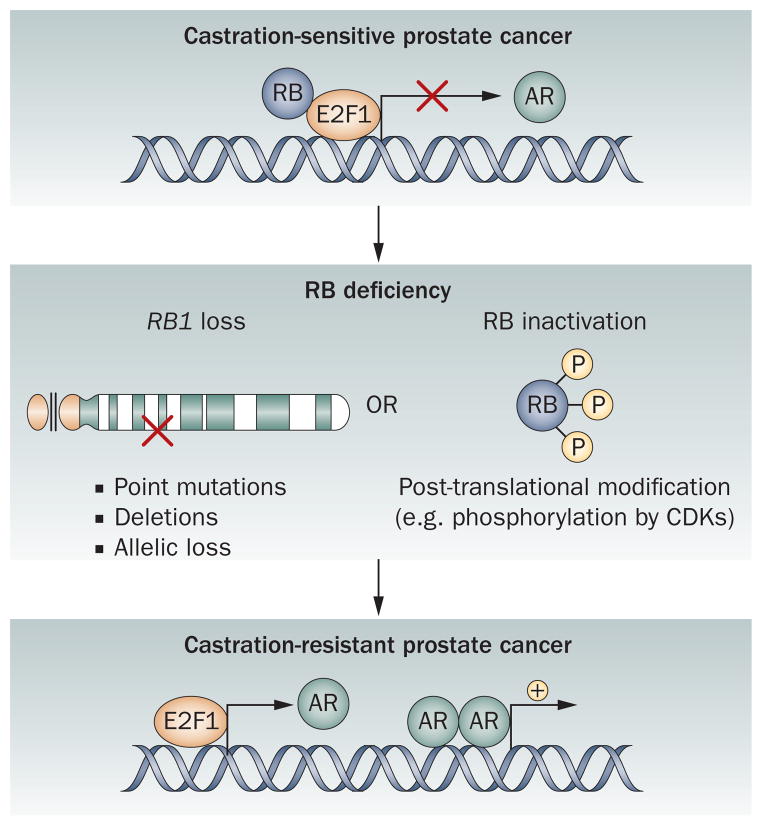

The underlying mechanisms by which RB loss or E2F1 activation facilitates a bypass of hormone therapy proved unexpected, and shed light on the unique means by which RB protects against tumor progression in the prostate. Strikingly, it was observed that RB directly controls expression of AR, whose activity is the target of androgen deprivation therapy. The tumor suppressor function of RB is thought to require the ability of the protein to bind DNA and control gene expression: in the context of prostate cancer, it was discovered that RB binds to regions responsible for controlling AR gene expression, thereby repressing AR mRNA expression and protein accumulation.21 Conversely, loss of RB resulted in upregulation of AR, promoted androgen-independent expression of AR target genes (such as PSA), and was sufficient to confer castration resistance in vivo. Moreover, investigation of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers from patients who failed hormone therapy revealed that RB-deficient tumors showed dramatically upregulated AR expression compared to tumors that achieved castration resistance with RB intact. Finally, the ability of RB loss to confer castration resistance proved to be dependent on heightened AR expression, as downregulation of AR by small interfering RNA (siRNA) resulted in loss of the castration-resistant phenotype induced by RB depletion.21 Subsequent studies in mouse models further support the contention that RB functions to prevent progression to invasive disease,39 although its impact on castration resistance was not assessed in this study. These collective observations put forward a new paradigm for RB as a selective suppressor of tumor progression in prostate cancer,40 and suggest that a central function of the protein is to prevent the transition to castration resistance through controlling receptor activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

RB controls prostate cancer progression. Loss of RB function via loss of the RB1 gene or through post-translational modifications that nullify tumor suppressor function occurs with high frequency in castration-resistant prostate cancer. In vivo modeling has revealed that RB controls expression of the gene encoding AR. Downregulation of RB leads to increased E2F1 transcription factor activity, upregulation of AR production, and resultant castration-resistant tumor growth. Abbreviations: AR, androgen receptor; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; RB, retinoblastoma.

The ability of RB loss to promote castration resistance is relatively unique among the tumor suppressors that are commonly altered in human disease, including PTEN and p53. Genetic alteration of the PTEN pathway or upregulation of PI3K signaling is frequently observed in metastatic disease. For example, loss of PTEN itself is more common in metastatic disease compared to primary disease (~42% versus ~4%, based on recent genomic profiling).41 The role of this tumor suppressor in tumor development and progression is unequivocal, yet its impact on progression to hormone-therapy resistance remains uncertain. In genetically engineered mouse models, PTEN loss promotes castration resistance; however, depletion of PTEN in human tumor xenografts does not ablate castration responsiveness.42 Similarly, p53-deficient cells respond to castration in mouse models,43 while a direct relationship between p53 loss and castration resistance in human disease has not been clearly demonstrated. These collective findings suggest that the impact of RB function on human disease may be distinct from that resulting from p53 or PTEN loss, which might explain the observed frequency of combined loss in advanced disease.

Tailoring therapy based on RB status

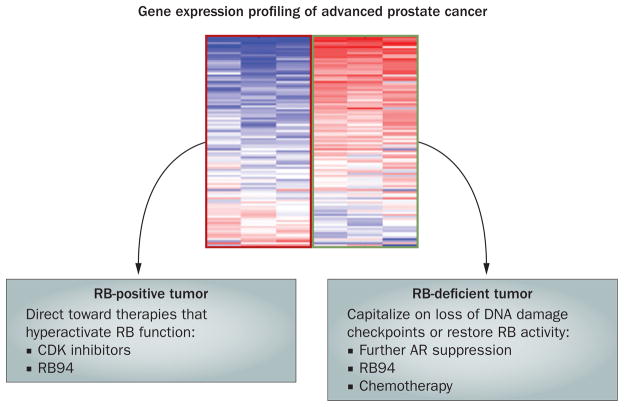

Assessment of RB function in the preclinical setting, combined with the known behavior of RB-deficient tumors in other tissue types, has led to the development of the enticing hypothesis that therapy for advanced prostate cancers could be tailored to RB status (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A conceptual model for stratification based on RB status. Assessment of RB status can be effectively determined through gene expression signature profiling. Recent studies support the hypothesis that RB tumor suppressor activity can be enhanced through the use of pharmacologic agents that heighten tumor suppressor activity (for example, CDK inhibitors and RB94). By contrast, tumors deficient in RB function would be expected to require further AR suppression, would potentially benefit from agents that restore RB activity (for example, RB94), and may be hypersensitive to selected chemotherapy agents that induce DNA damage. Abbreviations: AR, androgen receptor; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; RB, retinoblastoma; RB94, 94 kDa N-terminal truncated RB protein.

RB-positive tumors

In tumors that retain RB expression, it is speculated that hyperactivation of its tumor suppressor function could result in therapeutic gain. If clinically achievable, RB activation would be expected to afford suppressive effects with regard to cell cycle progression, but would also be anticipated to prevent AR upregulation and potentially delay the onset to castration resistance.

How to hyperactivate RB function in the clinical setting remains a subject of intensive investigation, but significant strides are being made toward this end. First, a tumor-targeting nanocomplex encoding RB94—a 94 kDa N-terminal truncated RB protein that results in specific and significant cytotoxicity to both RB-proficient and RB-deficient tumor cells44,45—has been delivered efficiently to bladder cancer subcutaneous xenografts after intravenous administration to the xenograft-bearing mice,46 and is currently in phase I clinical trials. Second, next-generation cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors might provide a robust means to engage RB tumor suppressor activity. Several CDKs in the G1 phase of the cell cycle promote cellular proliferation in part by directly phosphorylating the RB protein, thereby dampening the ability of RB to repress gene expression and exert tumor-suppressive activity. Although first-generation nonselective, pan-CDK inhibitors such as flavopiridol and CY-202 failed to provide reasonable clinical benefit, these disappointing outcomes have been attributed to the overt toxicity and off-target effects associated with these agents.47 A number of new CDK inhibitors are in early clinical trials,48–50 and PD-0332991, an oral inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6, has already shown good tolerability and preliminary evidence of clinical activity in phase I trials.51,52 Importantly, preclinical evidence suggests that PD-0332991 is particularly effective against RB-proficient tumors53,54 and displays synergy with hormonal manipulations in breast cancer cell lines.52 Thus, the influence of RB-activating agents on the response to androgen deprivation therapy should also be considered.

While intact RB function is required for responsiveness to CDK4 inhibitors, it should be noted that use of these agents could be particularly effective in tumors that have alterations in the MYC pathway. Recent evidence has solidified a role for MYC in both early and late-stage (invasive) disease,7,41,55 and although the role of MYC in tumors is complex, the ability of this oncogenic transcription factor to drive cell cycle progression is well established.56 It will be of interest to determine the frequency with which MYC alteration occurs in combination with RB deficiency in order to assess the impact of these combined events on human tumor phenotypes, and to further address the response to CDK4 inhibitors in this context.

RB-negative tumors

While RB-proficient tumors are expected to respond to hormone therapy and might benefit from adjuvant means of increasing RB function, treatment of RB-null or RB-deficient tumors presents a significant clinical challenge. As described above, most human tumors devoid of RB or defective in RB function are associated with high AR expression, poor outcomes, and resistance to hormone therapy—phenotypes that are recapitulated in preclinical models showing that RB depletion is sufficient to confer castration resistance.21 These observations beg the question of whether men whose absolute PSA value does not decrease to less than 0.2 ng/ml after androgen depletion (a strong independent predictor of survival in the metastatic setting)57,58 are in fact men with early loss of RB function. If so, perhaps monitoring of RB status could lead to early identification of these men, who might be candidates for further AR depletion strategies, early chemotherapy or treatment with novel agents.

Intriguingly, small-cell carcinoma of the prostate, an increasingly recognized finding in patients who display rapid progression of castration-resistant disease, is characterized by loss of RB expression (much like small-cell carcinomas arising in other organs like the lung),59 but also by loss of AR expression, indicating that, in the case of small-cell prostate cancers, RB loss utilizes alternative means of inducing aggressive disease phenotypes. It will be of critical importance to determine the molecular impact of RB perturbation in this tumor type. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that although the presence of small-cell morphology in prostate cancer predicts resistance to hormonal therapies, it also predicts a high response rate (albeit short-lived) to chemotherapy.60 This is in line with mounting evidence that RB deletion confers hypersensitization to a subset of DNA-damaging agents.61 Indeed, genetically defined model systems have shown that RB-deficient cells fail to sense and/or elicit cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage, thus leading to mitotic catastrophe and loss of cell survival. However, subsequent investigation of RB status and its impact on chemotherapy response in breast, lung, and prostate cancer preclinical models suggest that while RB-deficient tumor cells do show marked sensitization to chemotherapeutics, the observed effects are tissue and agent specific.23,27,62 In prostate cancer cells (not including small-cell prostate carcinoma), in vitro RB depletion resulted in modest sensitization to taxanes and topoisomerase inhibitors but not cisplatin, whereas lung and breast cancer cells depleted of RB showed increased susceptibility to platinating agents.

While the underlying basis for this selectivity remains to be fully understood, additional evidence to support the contention that the compromised response of RB-deficient cells to DNA damage can be exploited therapeutically comes from a number of clinical observations in different human malignancies. In breast cancer, tumors with low RB function are associated with improved response to chemotherapy in estrogen-receptor-negative disease.26,53,54,63 In bladder cancer, tumors with inactive RB showed an increased rate of pathologic complete response and clinical downstaging after neoadjuvant radiation therapy prior to cystectomy.64 In head and neck cancers, multiple clinical reports have shown that there is improved local control, improved disease-specific survival, and improved overall survival in patients with tumors carrying the human papillomavirus (HPV) when treated with either radiation therapy alone or combined with cisplatin-based chemotherapy.65,66 The oncogenic potential of this virus depends on sequestration and inactivation of the RB tumor suppressor. In fact, the endogenous CDK inhibitor p16, expression of which is frequently induced as a consequence of RB inactivation, is used as a marker for HPV positivity. A phase III multi-institutional trial found that HPV status (indicative of RB inactivation) was the major determinant for overall survival.67 This increased radiosensitivity and chemo-sensitivity has led the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) to begin to consider de-intensifying therapy in patients with head and neck cancers on the basis of p16 expression.

The specific role of p16 in prostate cancer remains incompletely defined. Biochemically, low p16 expression, which is thought to compromise RB function, was associated with an increased risk of distant metastases in RTOG 9202, and indicative of a subgroup of locally advanced tumors that exhibit distinct patterns of failure after long-term androgen deprivation therapy; however, investigation of locally advanced prostate cancer suggests that loss of RB and loss of p16 are not redundant.68,69 In both hormone-sensitive and castration-resistant prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo models, RB depletion led to increased radiosensitivity, apparently mediated through alterations in cell cycle checkpoints.70 In addition, overexpression of E2F1, a key target of RB, has also been shown to radiosensitize multiple prostate cancer model systems through induction of apoptosis.71 Further investigation is needed to determine the relationship between RB, p16, and the response to radiotherapy in prostate cancer.

Based on these collective findings, it is tempting to speculate that tumors harboring loss of RB expression or function may be particularly susceptible to radiation therapy and chemotherapeutic agents that directly induce DNA damage and/or promote genotoxic stress.

Conclusions and future directions

Substantive clinical evidence points toward a role for RB in protecting against prostate cancer progression, and preclinical modeling demonstrates that RB loss in human tumor xenografts promotes the transition to castration-resistant disease states. While these observations provide insight into the molecular underpinnings of disease progression, recent advances reviewed herein suggest that RB status is a solid candidate for development as a marker of transition to castration resistance and as a predictive marker of response to therapy that might guide therapeutic decisions. Critical challenges remain for addressing this postulate, and for further discerning the timing and relevance of RB perturbations. First, is RB a biomarker for poor response to AR-directed therapies? This concept should be formally tested, as RB loss promotes recruitment of AR to its target genes despite the presence of androgen blockade with first-generation antiandrogens. Second, are the new second-generation antiandrogens or CYP171A inhibitors effective in the setting of RB loss, or are substantive clinical or pathologic responses limited to the RB-proficient setting? Third, how does the role of RB in disease progression, clinical phenotypes, and therapeutic response vary in the transition to AR-positive, castration-resistant disease versus small-cell tumors? Similarly, the role of RB in the stem-cell-like or cancer-stem-cell population has yet to be definitively explored, and the effect of the microenvironment on the response to RB loss should be considered. Fourth, how can RB-deficient tumors be optimally managed? While current studies indicate that these tumors may be hypersensitive to a subset of chemotherapy agents, additional investigation is needed to identify the agents that are most effective in the RB-deficient setting and to determine whether the improved response to chemotherapy is durable. Fifth, does therapeutic activation or reintroduction of RB provide clinical benefit? This concept is intriguing and warrants further clinical investigation. Sixth, and perhaps most importantly, how can RB status be feasibly and definitively assigned? Immunodetection of the RB protein is not likely to be definitive; development of surrogate markers for RB function and/or utilization of gene signatures may improve identification of RB status. Additional consideration of this hurdle will be essential for truly assessing the utility of the RB pathway as a means of predicting clinical behavior.

In conclusion, it is apparent that the RB tumor suppressor has a significant role in protecting against the development of aggressive prostate cancer phenotypes, and that RB status substantially and differentially influences the response to hormone therapy and chemotherapy. While challenges remain with regard to harnessing this knowledge to improve clinical care, recent advances to this end suggest that further investigation is warranted.

Review criteria.

The articles selected for this review were chosen based on MEDLINE database searches to identify manuscripts on the subject of RB expression and function in the context of human malignancy. Additional emphasis was given to studies that assessed the potential impact of RB perturbation on therapeutic outcome in any tumor type, and assessment of RB status in clinical samples. While the focus remained on preclinical (for example, human tumor xenograft) and clinical implications of RB loss, parallels in mouse models of disease were also searched and included in the Review.

Key points.

The retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor is frequently lost or functionally inactivated in castration-resistant prostate cancer

RB protects against progression to castration resistance in part through modulation of androgen receptor expression and activity

Xenograft models of human prostate cancer suggest that RB downregulation contributes to the emergence of the castration-resistant phenotype

Although RB-deficient tumors may respond poorly to hormone therapy, evidence in multiple cancer types suggest that tumors low in RB exhibit a heightened initial response to chemotherapy

Tumor cells deficient in RB function show tissue-specific and context-specific loss of DNA damage checkpoints

RB status is a candidate for development as a pharmacodynamic marker of transition to castration resistance and as a predictive marker of response to therapy that might guide therapeutic decisions

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs Chris Logothetis, Angelo DeMarzo, Adam Dicker, Leonard Gomella, Kevin Kelly, and Erik Knudsen, the Greater Philadelphia Prostate Cancer Working Group, and Matthew Schiewer for critical discussion and comments. We would also like to thank Ms Beth Schade for technical and artwork assistance. We regret omission of additional citations due to space constraints. The authors are supported by grants from the NIH (CA099996 and CA116777 to K. E. Knudsen), US Department of Defense (to R. B. Den), and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to K. E. Knudsen and R. B. Den).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to researching data, discussing the content and writing the article and performing review/editing of the manuscript before submission.

Contributor Information

Ana Aparicio, Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology, Division of Cancer Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Robert B. Den, Departments of Cancer Biology, Urology, and Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University and Kimmel Cancer Center, 233 South 10th Street, BLSB 1008A, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

Karen E. Knudsen, Departments of Cancer Biology, Urology, and Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University and Kimmel Cancer Center, 233 South 10th Street, BLSB 1008A, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huggins C. Effect of orchiectomy and irradiation on cancer of the prostate. Ann Surg. 1942;115:1192–1200. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194206000-00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudsen KE, Penning TM. Partners in crime: deregulation of AR activity and androgen synthesis in prostate cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen BS, Vasioukhin V. Mechanisms of prostate cancer initiation and progression. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;109:1–50. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380890-5.00001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurel B, et al. Molecular alterations in prostate cancer as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic targets. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:319–331. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31818a5c19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen MF, Cavenee WK. Retinoblastoma and the progression of tumor genetics. Trends Genet. 1988;4:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knudsen ES, Knudsen KE. Tailoring to RB: tumour suppressor status and therapeutic response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:714–724. doi: 10.1038/nrc2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bookstein R, et al. Promoter deletion and loss of retinoblastoma gene expression in human prostate carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7762–7766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota Y, et al. Retinoblastoma gene mutations in primary human prostate cancer. Prostate. 1995;27:314–320. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990270604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkar FH, et al. Analysis of retinoblastoma (RB) gene deletion in human prostatic carcinomas. Prostate. 1992;21:145–152. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990210207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff JM, Brett LT, Lessells AM, Habib FK. Analysis of retinoblastoma gene expression in human prostate tissue. Urol Oncol. 1997;3:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(98)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips SM, et al. Loss of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene (RB1) is a frequent and early event in prostatic tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:1252–1257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks JD, Bova GS, Isaacs WB. Allelic loss of the retinoblastoma gene in primary human prostatic adenocarcinomas. Prostate. 1995;26:35–39. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990260108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ittmann MM, Wieczorek R. Alterations of the retinoblastoma gene in clinically localized, stage B prostate adenocarcinomas. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooney KA, et al. Distinct regions of allelic loss on 13q in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1142–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, et al. Identification of two distinct deleted regions on chromosome 13 in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 1998;16:481–487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma A, et al. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor controls androgen signaling and human prostate cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4478–4492. doi: 10.1172/JCI44239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knudsen ES, Wang JY. Targeting the RB-pathway in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1094–1099. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosco EE, et al. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor modifies the therapeutic response of breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:218–228. doi: 10.1172/JCI28803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markey MP, et al. Unbiased analysis of RB-mediated transcriptional repression identifies novel targets and distinctions from E2F action. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6587–6597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markey MP, et al. Loss of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor: differential action on transcriptional programs related to cell cycle control and immune function. Oncogene. 2007;26:6307–6318. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herschkowitz JI, He X, Fan C, Perou CM. The functional loss of the retinoblastoma tumour suppressor is a common event in basal-like and luminal B breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R75. doi: 10.1186/bcr2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma A, et al. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor status is a critical determinant of therapeutic response in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6192–6203. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bookstein R, Shew JY, Chen PL, Scully P, Lee WH. Suppression of tumorigenicity of human prostate carcinoma cells by replacing a mutated RB gene. Science. 1990;247:712–715. doi: 10.1126/science.2300823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banerjee A, et al. Changes in growth and tumorigenicity following reconstitution of retinoblastoma gene function in various human cancer cell types by microcell transfer of chromosome 13. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6297–6304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maddison LA, Sutherland BW, Barrios RJ, Greenberg NM. Conditional deletion of Rb causes early stage prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6018–6025. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, et al. Sex hormone-induced carcinogenesis in Rb-deficient prostate tissue. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6008–6017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day KC, et al. Rescue of embryonic epithelium reveals that the homozygous deletion of the retinoblastoma gene confers growth factor independence and immortality but does not influence epithelial differentiation or tissue morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44475–44484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill R, Song Y, Cardiff RD, Van Dyke T. Heterogeneous tumor evolution initiated by loss of pRb function in a preclinical prostate cancer model. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10243–10254. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Z, et al. Synergy of p53 and Rb deficiency in a conditional mouse model for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7889–7898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shappell SB, et al. Prostate pathology of genetically engineered mice: definitions and classification. The consensus report from the Bar Harbor meeting of the Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2270–2305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knudsen KE, Arden KC, Cavenee WK. Multiple G1 regulatory elements control the androgen-dependent proliferation of prostatic carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20213–20222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fribourg AF, Knudsen KE, Strobeck MW, Lindhorst CM, Knudsen ES. Differential requirements for ras and the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein in the androgen dependence of prostatic adenocarcinoma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Libertini SJ, et al. E2F1 expression in LNCaP prostate cancer cells deregulates androgen dependent growth, suppresses differentiation, and enhances apoptosis. Prostate. 2006;66:70–81. doi: 10.1002/pros.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun H, et al. E2f binding-deficient Rb1 protein suppresses prostate tumor progression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:704–709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015027108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macleod KF. The RB tumor suppressor: a gatekeeper to hormone independence in prostate cancer? J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4179–4182. doi: 10.1172/JCI45406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craft N, et al. Evidence for clonal outgrowth of androgen-independent prostate cancer cells from androgen-dependent tumors through a two-step process. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5030–5036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berges RR, et al. Cell proliferation, DNA repair, and p53 function are not required for programmed death of prostatic glandular cells induced by androgen ablation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8910–8914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu HJ, et al. Enhanced tumor suppressor gene therapy via replication-deficient adenovirus vectors expressing an N-terminal truncated retinoblastoma protein. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2245–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, et al. Adenoviral-mediated retinoblastoma 94 produces rapid telomere erosion, chromosomal crisis, and caspase-dependent apoptosis in bladder cancer and immortalized human urothelial cells but not in normal urothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:760–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirollo KF, et al. Tumor-targeting nanocomplex delivery of novel tumor suppressor RB94 chemosensitizes bladder carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2190–2198. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizzolio F, Tuccinardi T, Caligiuri I, Lucchetti C, Giordano A. CDK inhibitors: from the bench to clinical trials. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:279–290. doi: 10.2174/138945010790711978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle kinases in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malumbres M. Cyclins and related kinases in cancer cells. J BUON. 2007;12 (Suppl 1):S45–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lapenna S, Giordano A. Cell cycle kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:547–566. doi: 10.1038/nrd2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Dwyer PJ, et al. A phase I dose escalation trial of a daily oral CDK 4/6 inhibitor PD-0332991. 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25 (Suppl):3550. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slamon D, et al. Phase I study of PD 0332991, cyclin-D kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor in combination with letrozole ofr first-line treatment of patients with ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer [abstract 3060] J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 (Suppl):15s. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ertel A, et al. RB-pathway disruption in breast cancer: differential association with disease subtypes, disease-specific prognosis and therapeutic response. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4153–4163. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.20.13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Konecny GE, et al. Expression of p16 and retinoblastoma determines response to CDK4/6 inhibition in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1591–1602. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koh CM, et al. Alterations in nucleolar structure and gene expression programs in prostatic neoplasia are driven by the MYC oncogene. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1824–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soucek L, Evan GI. The ups and downs of Myc biology. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hussain M, et al. Absolute prostate-specific antigen value after androgen deprivation is a strong independent predictor of survival in new metastatic prostate cancer: data from Southwest Oncology Group Trial 9346 (INT-0162) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3984–3990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millikan RE, et al. Phase III trial of androgen ablation with or without three cycles of systemic chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5936–5942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahimi H, et al. Rb, PTEN and p53 tumor suppressor loss is common in prostatic small cell carcinoma. Presented at the United States & Canadian Academy of Pathology Annual Meeting; San Antonio, TX. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papandreou CN, et al. Results of a phase II study with doxorubicin, etoposide, and cisplatin in patients with fully characterized small-cell carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3072–3080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knudsen KE, et al. RB-dependent S-phase response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7751–7763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7751-7763.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zagorski WA, Knudsen ES, Reed MF. Retinoblastoma deficiency increases chemosensitivity in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8264–8273. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trere D, et al. High prevalence of retinoblastoma protein loss in triple-negative breast cancers and its association with a good prognosis in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1818–1823. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pollack A, et al. Retinoblastoma protein expression and radiation response in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:687–695. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lassen P, et al. Effect of HPV-associated p16INK4A expression on response to radiotherapy and survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1992–1998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindel K, Beer KT, Laissue J, Greiner RH, Aebersold DM. Human papillomavirus positive squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a radiosensitive subgroup of head and neck carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:805–813. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<805::aid-cncr1386>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ang KK, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chakravarti A, et al. Prognostic value of p16 in locally advanced prostate cancer: a study based on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 9202. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3082–3089. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chakravarti A, et al. Loss of p16 expression is of prognostic significance in locally advanced prostate cancer: an analysis from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocol 86–10. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3328–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Den R, et al. Relationship between the loss of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor and radiosensitivity [abstract 34] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 (Suppl 7):34. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Udayakumar T, Shareef MM, Diaz DA, Ahmed MM, Pollack A. The E2F1/Rb and p53/MDM2 pathways in DNA repair and apoptosis: understanding the crosstalk to develop novel strategies for prostate cancer radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]