Abstract

Purpose

During in vivo stem cell differentiation, mature cells often induce the differentiation of nearby stem cells. Accordingly, prior studies indicate that a randomly mixed coculture can help transform mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) into Nucleus Pulposus cells (NPC). However, because in vivo signaling typically occurs heterotopically between adjacent cell layers, we hypothesized that a structurally organized coculture between MSC and NPC will result in greater cell differentiation and proliferation over single cell type controls and cocultures with random organization.

Methods

We developed a novel bilaminar cell pellet (BCP) system where a sphere of MSC is enclosed in a shell of NPC by successive centrifugation. Controls were made using single-cell type pellets and coculture pellets with random organization. The pellets were evaluated for DNA content, gene expression, and histology.

Results

A bilaminar 3D organization enhanced cell proliferation and differentiation. BCP showed significantly more cell proliferation than pellets with one cell type and those with random organization. Enhanced differentiation of MSC within the BCP pellet relative to single cell type pellets was demonstrated by quantitative RT-PCR, histology, and in situ hybridization.

Conclusions

The BCP culture system increases MSC proliferation and differentiation as compared to single-cell type or randomly mixed co-culture controls.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cell, bilaminar pellet, coculture, proliferation, differentiation

Introduction

Harnessing the regenerative potential of stem cells is an important tissue engineering strategy. Consequently, developing effective techniques to direct stem cell differentiation has been an active area of research for many musculoskeletal tissues. For example, stem cell pellet approaches show promise as they selectively recapitulate aspects of the embryonic microenvironments for regenerative purposes (Caplan, et al. 1997; Hall, et al. 2000; Lee, et al. 2001; Ichinose, et al. 2005; Eames, et al. 2008; Merill, et al. 2008).

Our approach focuses on the intervertebral discs of the spine. The intervertebral disc is composed of a peripheral annulus fibrosus and a central nucleus pulposus (NP). The NP contains chondrocyte-like cells (NPC) embedded in a matrix of proteoglycan and type II collagen that is highly hydrophilic and causes the tissue to swell and resist compression hydrostatically (Urban, et al. 2000). This avascular tissue is a high-pressure, ischemic environment that is challenging for cell function and survival and often leads to disc degeneration (Turner, et al. 1992). The goal of intervertebral disc repair is to re-establish pain-free motion by restoring its physical and biochemical properties.

Many regenerative strategies include delivering rejuvenated, synthetically-active cells. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are attractive for this purpose because they can differentiate into NPC-like cells (Yoo, et al. 1998). This approach has been used in several in vivo studies, yet the long-term functional regeneration of adult discs has not been achieved (Crevensten, et al. 2004; Sakai, et al. 2005; Zhang, et al. 2005).

The benefits of MSC/NPC coculture have been demonstrated by several groups. In these systems, paracrine signaling induces differentiation and proliferation of MSC and NPC (Yang, et al. 2008), and beneficial effects are greater with cell-cell contact (Yamamoto, et al. 2004; Le Visage, et al. 2006). For example, Richardson et al. (2006) demonstrated MSC differentiation into NPC in monolayer with MSC-NPC contact. They observed that a 75%NPC:25%MSC ratio was optimum for MSC differentiation, which was the basis of our selection of this ratio. This ratio also takes advantage of the fact that MSC are much easier to procure than their adult NPC counterpart, which is a practical consideration for future development of technology. Several studies have since made similar observations in 3D culture using a random mixture of MSC and NPC (Vadal, et al. 2008; Chen, et al. 2009; Wei, et al. 2009). These experiments highlight the beneficial signaling effects of coculture. However, the approaches don’t take advantage of heterotypic signaling (across an interface) and homotypic signaling (within the layer of the same cell type) that accompanies 3D organization and is part of natural organ development processes.

We report here on a spherical bi-laminar cell pellet (BCP) approach that structures cell-cell signaling between MSC and NPC in a 3D culture system where one cell type forms an inner sphere enclosed within a shell formed by the other cell type. Our hypothesis is that organized coculture between MSC and NPC will result in greater cell differentiation and proliferation over single cell type controls and cocultures with random organization. To test our hypothesis, we used our recently described structured coculture pellet method that creates a 3D tissue induction interface between stem cells and disc cells (Allon, et al. 2009).

Materials and methods

Cell Culture

Adult bovine NPC were isolated from caudal discs of 4 different animals and digested in 0.5% collagenase and 2% antibiotic in low glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) at 37°C. The cells were then pooled and expanded to the 4th passage in NPC Media (DMEM with 1% antibiotic/antimycotic, 1.5% 400 mOsm, and 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS)) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Commercially available human MSC were purchased (Lonza, Switzerland). Cells were sourced from three different donors, pooled, and expanded to the 7th passage in growth media (DMEM, 1% antibiotic, and 10% FBS) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Human NPC were obtained from a consenting 55-year-old female patient undergoing surgery for scoliosis and processed similarly to the bovine NPC. In addition, bovine MSC were isolated from femur tissue.

Pellet formation

Three different types of pellets were formed, each consisting of 500,000 cells total: pellets of 100% one cell type, pellets of MSC and NPC with randomized organization, and pellets of MSC and NPC organized in a BCP. The coculture pellets were formed with 3 different ratios of 25/75, 50/50, and 75/25 respectively (Figure 1). Human MSC were mixed with Bovine NPC for all the experiments. The other combinations (Human MSC with Human NPC, Bovine MSC with Bovine NPC) were tested as controls for cross-species interactions. The human MSC and bovine NPC were selected for coculture as a means for tracing the cells at later times based on their species for both immunohistochemistry and for gene expression. This enabled us to isolate the behavior of the MSC and NPC in culture.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the eleven different experimental groups indicating their compositions, structures, and ratios.

For the single cell-type pellets (SCP), cells were pipetted into a 15mL polypropylene tube and centrifuged at low speeds (300g) for 5min. For the randomized pellets, both cell types were added to the same tube and centrifuged at 300g for 5min. For the BCP, the cell type that would form the inner sphere of the pellet was centrifuged at 300g for 5min. Subsequently, the second cell type that would form the outer shell was gently added to the same tube. The cells were then centrifuged again at low speed for 5 min. BCP were formed with MSC on the inside (MSCin) and NPC on the outside (NPCout) and vice versa with MSC on the outside (MSCout) and NPC on the inside (NPCin). All pellets were cultured in 2 mL of growth media for 3days and then transferred to ultra-low attachment 24 well plates (Corning).

To control for the effects of FBS, some pellets were also cultured in serum-free media (High glucose DMEM, 1% Antibiotic / Antimitotic, 1% insulin–transferrin–selenious acid mix, 100 µg/ml sodium pyruvate, 40 µg/ml l-proline, 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, with 100 nM Dexamethasone). In addition, MSC SCP were cultured for 3weeks in chondrogenic media (serum-free media supplemented with 5ng/mL of TGF-beta1 (Peprotech, NJ)). They were compared to 75%MSCin:25%NPCout BCP both in growth media and chondrogenic media.

Measuring DNA content

Pellets were digested in papain (20U/mL in PBS) at 60°C overnight and assayed with a Quant-iT PicoGreen kit (Invitrogen, CA) to measure DNA content at 525nm absorption. Overall, 11 pellet groups were generated (Figure 1) and for 3 time points (1, 2, and 3 weeks). The sample size was n = 10 per group. DNA content was converted to cell numbers by approximating that 6pg of DNA are in each cell.

Histology and In Situ hybridization

The pellets were fixed and paraffin embedded. The sections were stained with Safranin-O. Within the BCP, we localized the human MSCs using human specific antibodies Lamp1 and Lamp2 (Abcam, MA), and in all pellets we localized aggrecan using protein specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnoloy, CA). In situ hybridization was used to identify aggrecan and collagen producing cells (Albrecht, et al. 1997). Sections were hybridized with 35S-labeled human riboprobes to aggrecan and col2a1 and counterstained with Hoechst dye (Sigma, MO). Hybridization signals were detected using illuminated darkfield and the nuclear stain visualized with epifluorescence.

Quantitative RT-PCR

At 3weeks, MSC SCP, NPC SCP, and 75%MSCin:25%NPCout were harvested for RNA extraction. In order to have sufficient amounts of RNA, 5 pellets were pooled per group per time point. There was a total n=5 pooled samples for each group. RNA was extracted with a QIAshredder kit and an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA).

Primers were carefully selected to be species specific and only detect the gene expression of the human MSC in one instance and the bovine NPC in the other. The samples were analyzed using Taqman species specific primers for the following human and bovine genes: beta-2-microglobulin (B2M), Sox9, aggrecan, collagen I (col1), collagen II (col2), collagen X (colX), and matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) (Applied Biosystems, CA).

All measurements were conducted in triplicate and each sample was normalized to the housekeeping gene B2M which was invariant with respect to the condition. The ddCt method (Pfaffl 2001) was used to measure the fold change of the human MSC and the bovine NPC separately which we were able to distinguish using the species specific primers. Two controls were used, one for each of the cell types: the control for the human MSC in the pellet was the 3 week human MSC SCP and the control for the bovine NPC in the pellet was the bovine 3 week NPC SCP. The fold change for all the genes mentioned above was calculated against the appropriate control in each instance.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were preformed using JMP statistical software (Version 5.0). Standard analysis of variance procedures were performed to compare group means and to estimate the effect of the specimen group variables. The Tukey-Kramer test was used to determine pair-wise statistical differences. An alpha of 0.05 was used to interpret statistical significance.

Results

Controls for cross species interaction and the effects of FBS

Consistent with prior reports (Allon, et al. 2009), we observed no significant differences between single species and cross-species pellets, therefore all the other experiments were performed using Human MSC and Bovine NPC. We also observed no significant differences between using growth media or serum free media, therefore all other experiments were performed using growth media

DNA Content

At 1 week, there were no significant differences between groups (Figure 2). At 2 weeks, MSC and NPC SCP did not experience any significant increase in cell numbers. The coculture pellets had a significantly higher DNA content than SCP (p<0.0001). In addition, the ratio of 50/50 significantly increased cell numbers over the ratio of 25%MSC:75%NPC (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Graph of the number of cells per pellet for each time point, conformation, and ratio. Pellets are made with human MSC and bovine NPC cultured in growth media.

At 3 weeks, structural organization and ratio were both significant predictors of cell numbers. The coculture groups were significantly different from one another with MSCin:NPCout having the most DNA content followed by MSCout:NPCin, and finally random structure having the least (p<0.0001). The ratio of 25%MSC:75%NPC and the ratio of 50/50 were significantly higher than SCP (p<0.0001). SCP and the randomized pellets experienced a four-fold increase in cell number as compared to 1week. By contrast, BCP experienced a ten-fold increase in cell number, with the 50%MSCin:50%NPCout reaching a fourteen-fold increase. Overall, the 50%MSCin:50%NPCout BCP had significantly more DNA content than all other pellets (p<0.0001) except for 25%MSCin:75%NPCout that was not significantly different.

Histology and In situ hybridization

The sections were stained with Safranin-O to qualitatively detect the presence of proteoglycan (red staining). The MSCin:NPCout pellets stained more vibrantly (Figure 3). The human specific antibody enabled us to confirm that the desired configuration was made and maintained throughout the culture time (Figure 4 A–D).

Figure 3.

A–C 3week pellets stained with Safranin-O (red indicates proteoglycan). Pellets are made with human MSC and bovine NPC culture in growth media. A) MSC pellets. B) NPC pellets. C) MSCin50:NPCout50 pellets.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry (counterstained with hematoxylin): A–F are stained with Lamp1&2 (human specific) antibody. G–L are stained with Aggrecan antibody (counterstained with Hoechst dye). M-R show the location of Aggrecan gene expression. S–X show the location of col2 gene expression.

For the MSCin:NPCout group at 1 week, the NPC expressed aggrecan, while the MSC did not (Figure 6 images A, G, M). However, at 3 weeks, aggrecan protein and RNA is localized throughout the pellet (Figure 4 images B,H, N). Col2 expression also increased throughout the pellet over time (Figure 4 image T).

For the NPCin:MSCout group, at 1 week the aggrecan protein and RNA localized to the pellet periphery and in a central pocket where NPC were located (Figure 4 images C, I, O). At 3 weeks, the aggrecan was expressed throughout the pellet, however, the central NPC appear to have lower levels of RNA expression (Figure 4 images D, J, P). There appears to be a slight increase in expression of col2 on the periphery of the pellet at three weeks (Figure 4 image V).

MSC exhibited faint staining of aggrecan protein and no staining of aggrecan or collagen RNA (Figure 4 images E, K, Q, W). NPC exhibited aggrecan protein staining throughout (Figure 4 images F, L, R) but aggrecan RNA was not uniform, with a pronounced ring of expression on the periphery of the pellet with some central staining. Col2 RNA was very faintly expressed (Figure 4 image X).

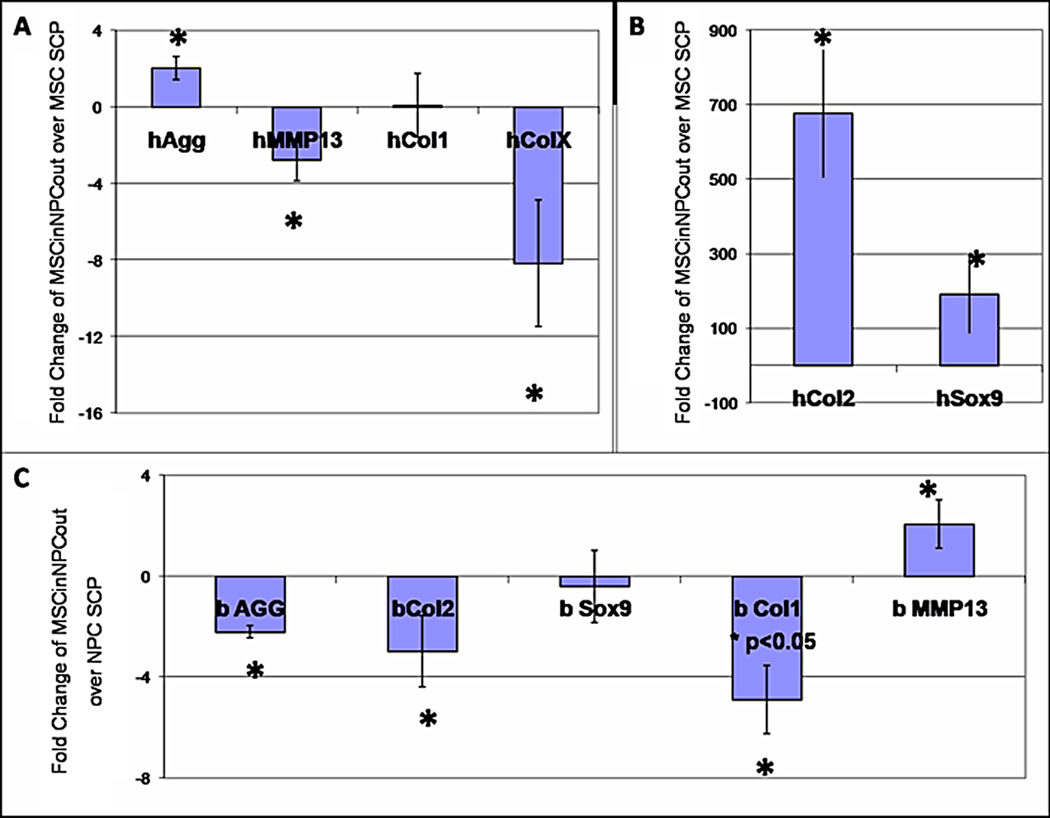

Quantitative RT-PCR

We were able to distinguish the gene expression of the MSC and NPC within the 75%MSCin:25%NPCout BCP by using species-specific primers. The fold change was calculated with the species appropriate SCP (MSC for human and NPC for bovine). The MSC in the BCP had a 2-fold upregulation of aggrecan, a 675.5-fold upregulation of col2, a 190.3-fold upregulation of Sox9, a 2.7-fold downregulation of MMP13, and an 8.2-fold downregulation of colX (p<0.05) (Figure 5). Col1 gene expression showed no significant differences.

Figure 5.

Quantitative RT-PCR with species-specific Taqman primers was performed on 3week pellets: MSC, NPC, and 75%MSCin:25%NPCout. Readings were normalized to the housekeeping gene B2M. For human genes in coculture pellets, the fold change was calculated using the MSC SCP. For bovine genes in coculture pellets, the fold change was calculated using the NPC SCP.

The NPC in the BCP had a 2.2-fold downregulation of aggrecan, a 2.9-fold downregulation of col2, a 4.9-fold downregulation of col1, and a 2-fold upregulation of MMP13. The levels of Sox9 gene expression showed no difference.

Discussion

We envision that cell-based therapies will eventually be used to treat disc degeneration (Rengachary, et al. 2002; Allon, et al. 2010), which is the focus and motivation of the continued efforts in the field. Since notochordal cells are neither readily available nor practical for disc tissue engineering, it is fortunate that other cell types have also been shown to stimulate nucleus cells for the purposes of disc regeneration. For example, nucleus cells can be “reactivated” by co-culture with annulus fibrosus cells and, upon reinsertion in vivo, the reactivated nucleus cells retarded disc degeneration (Okuma, et al. 2000). Conversely, native nucleus cells can signal donor cells. For instance, under certain co-culture conditions with nucleus cells, adipose stem cells can be induced toward the nucleus-like phenotype (Lu, et al. 2007). Similar results have been reported for MSCs where monolayer contact with nucleus cells can cause them to differentiate into nucleus-like cells as evidenced by up-regulation of Sox-9, aggrecan, and collagen II (Yamamoto, et al. 2004; Le Visage, et al. 2006; Richardson, et al. 2006; Vadala, et al. 2008). Co-culture studies with chondrocytes and MSCs suggest morphogenetic factors secreted by chondrocytes (TGF-β and IGF-1) induce MSC differentiation and proliferation (Liu, et al. 2010). Importantly, in these monolayer co-culture situations, the quantity of disc matrix synthesized was dependent on the ratio of respective cell type, with the optimal ratio being 3 nucleus cells for each MSC. However, since the density of nucleus cells in degenerated discs is low, this optimal cell ratio would be difficult to achieve in practice by injecting MSCs alone. In contrast, we have devised a bilaminar cell pellet (BCP)-based therapeutic approach, with the pellet composed of undifferentiated MSCs and mature NPCs, where the cell-cell interactions are pre-orchestrated in vitro.

The goal of this study was to assess whether a 3D bilaminar coculture of MSC and NPC, which allowed for structured homotypic and heterotypic interactions, would enhance cell proliferation and differentiation. We have previously shown that BCP produce significantly more aggrecan protein than single cell type pellets (Apple, et al. 2008). Our data here indicate that BCP also result in significantly more cell proliferation, have favorable gene expression profiles, and appear to enhance MSC differentiation.

MSC:NPC interactions significantly affected the total number of cells in the pellet (Figure 2). At 3 weeks, pellet structure and cell ratio both became statistically significant predictors of cell number. While future studies involving FACS sorting would help elucidate which cell type is proliferating, our results show that the pellets benefited from more structural organization to fully exploit the trophic effects of coculture. In addition, histologic analyses indicated a qualitative boost in matrix synthesis in the BCP group (Figure 3). These data together indicate an increase in proliferation and matrix synthesis which are both desirable for a tissue engineering solution.

Additionally, BCP induce MSC differentiation toward an NPC-like phenotype, with significant increases in expression of aggrecan, col2, and Sox9 (Figure 5). Importantly, the downregulation of colX and MMP13 are indicative of the advantage of using coculture techniques in differentiating MSC as opposed to growth factors (Mueller, et al. 2010). MMP13 is commonly expressed in diseased discs and causes further degeneration of the tissue; its upregulation would hinder any therapeutic effect the BCP would provide. In situ hybridization provided further insight by showing that MSC within the MSCin:NPCout pellet began both expressing and secreting aggrecan over 3 weeks of culture time (Figure 4). The NPC within the MSCin:NPCout pellets down-regulated aggrecan and col2 but maintained Sox9 gene expression levels. This may be indicative of the NPC’s signaling role within the BCP as opposed to their purely secretory role in the NPC.

Overall, our experiments demonstrate an advantage to structured co-culturing with MSC on the inside and NPC on the outside. This may be due to the fact that MSC propagate signals more readily amongst themselves than with other cell types (D’Andrea, et al. 1996; D’Andrea, et al. 1998; Zhang, et al. 2002; Valiunas, et al. 2004), and that the internal microenvironment within the BCP may favor chondrogenic differentiation via growth-related pressurization and diminished oxygen availability. It is possible the BCP’s organized signaling interface between MSC and NPC exploits this feature. Future studies will include testing BCP performance in culture conditions that more closely mimic the painful disc environment (ischemia and inflammation), as well as measuring paracrine effects on host disc cells. In previous work, we have shown in a rat model that BCP can rescue a degenerating disc with significantly better disc height, disc quality, and implanted cell retention at a 5 week time point than SCP and injected cells in a fibrin suspension (Okuma, et al. 2000). Ultimately, we anticipate that beneficial BCP features reported here will provide measurable advantages for nucleus regeneration in small and large animal pre-clinical studies.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH R01AR052712 to JCL and by NIDCR DE016402 and NIAMS R21 AR052513 to RAS.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- MSC

Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- NPC

Nucleus Pulposus Cells

- BCP

Bilaminar Cell Pellet

- NP

Nucleus Pulposus

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

- SCP

Single Cell-type Pellets

- MSCin

MSC on the inside

- NPCout

NPC on the outside

- MSCout

MSC on the outside

- NPCin

NPC on the inside

References

- 1.Albrecht UEG, Eichelle G, Helms JA. Visualization of gene expression patterns by in situ hybridization; in CRC Press. In: Daston GP, editor. Molecular and cellular methods in developmental toxicology. CRC Press; 1997. pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allon AA, Schneider RA, Lotz JC. Coculture of Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Nucleus Pulposus Cells in Bilaminar Pellets for Intervertebral Disc Regeneration. SAS Journal. 2009;3:41–49. doi: 10.1016/SASJ-2009-0005-NT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allon AA, Aurouer N, Yoo BB, Liebenberg EC, Buser Z, Lotz JC. Structured co-culture of stem cells and disc cells prevent degeneration in a rat model. Spine J. 2010;10(12):1089–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apple A, Schneider RA, Lotz JC. Structured Co-culture of Stem Cells and Disc Cells Enhances Matrix Synthesis. Proceedings of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine; May 2008; Spine Week Geneva, Switzerland. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caplan AI, Elyaderani M, Moshizuki Y, Wakitani S, Goldberg S, Goldberg VM. Principles of cartilage repair and regeneration. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;342:254–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Emery SE, Pei M. Coculture of synovium-derived stem cells and nucleus pulposus cells in serum-free defined medium with supplementation of transforming growth factor-beta1. Spine. 2009;34(12):1272–1280. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a2b347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crevensten G, Walsh AJ, Ananthakrishnan D, Page P, Wahba GM, Lotz JC, Berven S. Intervertebral disc cell therapy for regeneration: mesenchymal stem cell implantation in rat intervertebral discs. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:430–434. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017545.84833.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Andrea P, Vittur F. Gap Junctions mediate intercellular calcium signaling in cultured articular chondrocytes. Cell Calcium. 1996;20(5):389–397. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Andrea P, Calabrese A, Grandolfo M. Intercellular calcium signaling between chondrocytes and synovial cells in coculture. Biochem J. 1998;329:681–687. doi: 10.1042/bj3290681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eames BF, Schneider RA. The genesis of cartilage size and shape during development and evolution. Development. 2008;135(23):3947–3958. doi: 10.1242/dev.023309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall BK, Miyake T. Divide, accumulate, differentiate: cell condensation in skeletal development revisited. Int J Dev Biol. 1995;39:881–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall BK, Miyake T. All for one and one for all: condensations and the initiation of skeletal development. BioEssays. 2000;22:138–147. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<138::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichinose S, Yamagata K, Sekiya I, Muneta T, Tagami M. Detailed examination of cartilage formation and endochondral ossification using human mesenchymal stem cells. Clin and Exp Pharm and Phys. 2005;32:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JY, Hall R, Pelinkovic D, Cassinelli E, Usas A, Gilbertson L, Huard J, Kang J. New Use of a Three-Dimensional Pellet Culture System for Human Intervertebral Disc Cells. Spine. 2001;26:2316–2322. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Visage C, Kim SW, Tateno K, Sieber AN, Kostuik JP, Leong KW. Interaction of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Disc Cell: Changes in Extracellular Matrix Biosynthesis. Spine. 2006;31:2036–2042. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231442.05245.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Sun H, Yan D, Zhang L, Lv X, Liu T, Zhang W, Liu W, Cao Y, Zhou G. In vivo ectopic chondrogenesis of BMSCs directed by mature chondrocytes. Biomaterials. 2010;31(36):9406–9414. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu ZF, Zandieh Doulabi B, Wuisman PI, Bank RA, Helder MN. Differentiation of adipose stem cells by nucleus pulposus cells: configuration effect. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359(4):991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrill AE, Eames BF, Weston SJ, Health T, Schneider RA. Mesenchym dependent BMP signaling directs the timing of mandibular osteogenesis. Development. 2008;135(7):1223–1234. doi: 10.1242/dev.015933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller MB, Fischer M, Zellner J, Bernaer A, Dienstknecht T, Prantl L, Kujat R, Nerlich M, Tuan RS, Angele P. Hypertrophy in mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis: effect of TGF-beta isoforms and chondrogenic conditioning. Cells Tisues Organs. 2010;192:158–166. doi: 10.1159/000313399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuma M, Mochida J, Nishimura K, Sakabe K, Seiki K. Reinsertion of stimulated nucleus pulposus cells retards intervertebral disc degeneration: an in vitro and in vivo experimental study. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(6):988–997. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rengachary S, Balabhadra RS. Black disc disease: a commentary. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;13(2):E14. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.13.2.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson SM, Walker RV, Parker S, Rhodes NP, Hunt JA, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. Intervertebral Disc Cell-Mediated Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:707–716. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakai D, Mochida J, Iwashina T, Watanabe T, Nakai T, Ando K, Hotta T. Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells transplanted to a rabbit degenerative disc model potential and limitations for stem cell therapy in disc regeneration. Spine. 2005;30:2379–2387. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000184365.28481.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner JA, Ersek M, Herron L, Haselkom J, Kent D, Ciol MA, Deyo R. Patient outcomes after lumbar spinal fusions. JAMA. 1992;268(7):907–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urban JPG, Roberts S, Raphs JR. The nucleus of the intervertebral disc from development to degeneration. Amer Zool. 2000;40:5–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vadala G, Studer RK, Sowa G, Spiezia F, Iucu C, Denaro V, Gilbertson LG, Kang JD. Coculture of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and nucleus pulposus cells modulate gene expression profile without cell fusion. Spine. 2008;33(8):870–876. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816b4619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valiunas V, Doronin S, Valiuniene L, Potapova I, Zuckerman J, Walcott B, Robinson RB, Rosen MR, Brink PR, Cohen IS. Human mesenchymal stem cells make cardiac connexins and form functional gap junctions. J Physiol. 2004;555(Pt 3):617–626. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei A, Chung SA, Tao H, Brisby H, Lin Z, Shen B, Ma DD, Diwan AD. Differentiation of rodent bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into intervertebral disc-like cells following coculture with rat disc tissue. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(9):2581–2595. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2008.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto Y, Mochida J, Sakai D, Nakai T, Nishimura K, Kawada H, Hotta T. Upregulation of the Viability of Nucleus Pulposus Cells by Bone Marrow-Derived Stromal Cells: Significance of Direct Cell-to-Cell Contact in Coculture System. Spine. 2004;29:1508–1514. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000131416.90906.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang SH, Wu CC, Shih TT, Sun YH, Lin FH. In vitro study on interaction between human nucleus pulposus cells and mesenchymal stem cells through paracrine stimulation. Spine. 2008;33(18):1951–1957. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817e6974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo J, Barthel TS, Nishimura K, Solchaga L, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Johnstone B. The chondrogenic potential of human bone-marrow derived mesenchymal cells. J Bone and Joint Surgery. 1998;80A(12):1745–1757. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W, Green C, Stott NS. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 modulation of chondrogenic differentiation in vitro involves gap junction-mediated intercellular communication. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193(2):233–243. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang YG, Guo X, Kang LL, Li J. Bone mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into rabbit intervertebral discs increase proteoglycans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;430:219–226. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000146534.31120.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]