Abstract

Tobacco smoking using a waterpipe (narghile, hookah, shisha) has become a global epidemic. Unlike cigarette smoking, little is known about the health effects of waterpipe use. One acute effect of cigarette smoke inhalation is dysfunction in autonomic regulation of the cardiac cycle, as indicated by reduction in heart rate variability (HRV). Reduced HRV is implicated in adverse cardiovascular health outcomes, and is associated with inhalation exposure-induced oxidative stress. Using a 32 participant cross-over study design, we investigated toxicant exposure and effects of waterpipe smoking on heart rate variability when, under controlled conditions, participants smoked a tobacco-based and a tobacco-free waterpipe product promoted as an alternative for “health-conscious” users. Outcome measures included HRV, exhaled breath carbon monoxide (CO), plasma nicotine, and puff topography, which were measured at times prior to, during, and after smoking. We found that waterpipe use acutely decreased HRV (p<0.01 for all measures), independent of product smoked. Plasma nicotine, blood pressure, and heart rate increased only with the tobacco-based product (p<0.01), while CO increased with both products (p<0.01). More smoke was inhaled during tobacco-free product use, potentially reflecting attempted regulation of nicotine intake. The data thus indicate that waterpipe smoking acutely compromises cardiac autonomic function, and does so through exposure to smoke constituents other than nicotine.

Keywords: nervous system, autonomic, smoking, heart rate variability, shisha, hookah

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, tobacco use accounts for approximately 5 million deaths per year, mainly due to the use of cigarettes. The causal link between cigarette smoking and early death and disease has long been known, but the health effects of other methods of using tobacco are less well studied, including tobacco smoking through a waterpipe (aka shisha, hookah, narghile). Though centuries old, the practice of waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) has exploded in popularity since the early 1990’s, particularly among youth (Grekin & Ayna, 2012).1 Traditionally associated with cultures of Southwest Asia and North Africa, where reported current use rates in various populations now range from 20–45% (Saade et al., 2009; Almerie et al., 2008; Azab et al., 2010), surveys in Canada (Roskin & Aveyard, 2009), Estonia (Pärna et al., 2008), Denmark (Jensen et al., 2010), and South Africa (Combrink et al., 2010) indicate that there is a growing worldwide epidemic of WTS (Martinasek et al., 2011). The United States (U.S.) is not immune. Among 105,000 U.S. university students surveyed in 2008, 30% reported “ever use” of a waterpipe to smoke tobacco, and WTS was the second most commonly reported tobacco use method (cigarettes were first; Primack et al., in press). WTS is also reported by U.S. adolescents; in a nationwide sample of 14,900 U.S. 12th graders, 18.5% reported past-year WTS (Johnston et al., 2011).

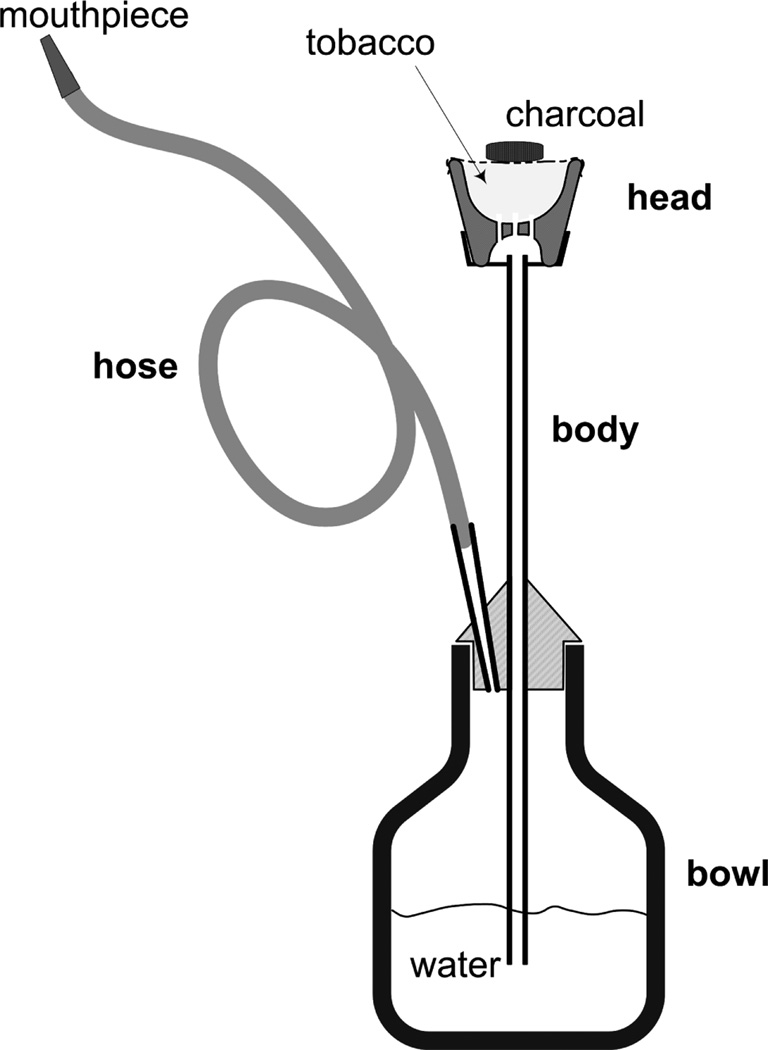

WTS involves the use of burning charcoal, often in conjunction with a flavored tobacco-based mixture known as ma’assel (Figure 1). When a user puffs from the mouthpiece, air is drawn through and heated by the charcoal and into the tobacco product to produce smoke. The smoke therefore comprises fumes emanating from both the charcoal and the tobacco, and contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), volatile aldehydes, carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide(NO), nicotine, furans, and nanoparticles (Daher et al., 2010; Katurji et al., 2010; Monn et al., 2007; Schubert et al., 2011; Schubert et al., 2012; Shihadeh et al., 2012). Carboxyhemoglobin and plasma nicotine levels rise during waterpipe use (Blank et al., 2011) and metabolites of PAH and tobacco specific nitrosamines can be measured in the urine of waterpipe smokers (Jacob et al., 2011). Thus, waterpipe tobacco smoke contains toxicants to which users are exposed systemically. Not surprisingly then, like cigarette smoking, WTS has been linked to reduced birth weight (Nuwayhid et al., 1998), genetic damage (Khabour et al., 2011), and respiratory disease (Al Mutairi et al., 2006; Raad et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Schematic of a narghile waterpipe, whose main components are a head, body, water bowl, and hose. The tobacco-containing or tobacco-free product is loaded into the head, and burning charcoal is placed on top of it (usually the tobacco is separated from the charcoal by a piece of perforated aluminum foil). When a user inhales from the mouthpiece, air and hot charcoal fumes are drawn through the tobacco product, producing smoke. The smoke exits from the bottom of the head, into the body, and through the water and hose to the user. The waterpipe illustrated here, and used in this study uses an approximately 3 cm deep head that can be filled with 10–20 g of product. Figure adapted from Monzer et al. (2008).

In addition to these and other diseases, cigarette smoking – even smoking a single cigarette – acutely compromises autonomic nervous system (ANS) cardiac control. A non-invasive measure of ANS dysfunction is reduced heart rate variability (HRV), the variation in time between successive heart beats during a given measurement period. In a healthy individual at rest, variation in HRV reflects the normal response of the ANS to continuously vary signaling mechanisms in the body (Dinas et al., in press). Decreases in HRV predict risk of coronary heart disease and mortality (Tsuji et al., 1996; Dekker et al., 2000), are associated with increased systemic inflammation (von Känel et al., 2011), and are associated with an increase in arrhythmia susceptibility after short-term second-hand smoke exposure (Chen et al., 2008). While its clinical interpretations remain a subject of research, HRV as an indicator of ANS cardiac function is widely used in the exposure sciences as a biomarker of environmental insult (Brook et al., 2010).

The hyper-acute effects of cigarette smoking on reducing HRV (Hayona et al., 1990; Karakaya et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2005) are normally attributed to nicotine in up-regulating catecholamine release (Dinas et al., in press). However, respirable particles and other combustion-derived components in cigarette smoke may also reduce HRV (Dinas et al., in press), and may do so through pathways active in acutely reducing HRV in humans and animals exposed to concentrated urban air pollutants (Peters & Pope, 2002; Rodriguez Ferreira Rivero et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2008; Min et al., 2009; Riojas-Rodriguez et al., 2006). Thus, WTS, that also involves inhalation of large quantities of a variety of combustion-derived constituents, may also influence HRV acutely, and may do so independently of the nicotine pathway.

To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has investigated influences of waterpipe smoking on HRV. In this report we describe measurements made of acute changes in HRV, plasma nicotine, and CO associated with a waterpipe use episode. In addition, we compared the acute effects of smoking a waterpipe loaded with tobacco with those of smoking a tobacco-free “herbal” mixture that is advertised as a product for the “health-conscious” waterpipe user (http://www.soex.com/e/herbalmolasses.html). This product does not deliver nicotine (Blank et al., 2011), but like its tobacco-based counterpart, its smoke contains “tar”, CO, NO, PAH, and volatile aldehydes (Shihadeh et al., 2012). We hypothesized that smoking a waterpipe, like cigarette smoking, would reduce HRV and that this influence would be independent of the nicotine delivery of the product smoked in the waterpipe.

Measures of HRV used in this study included low frequency power (LF), high frequency power (HF), and sample entropy (SampEn; Richman & Moorman, 2000). LF and HF are computed using spectral analysis of interbeat (R to R wave) intervals. While HF is commonly accepted as a measure of parasympathetic autonomic system activity, interpretation of LF has been controversial. Conventionally used as a quantitative marker of sympathetic nervous system activation, mounting evidence supports the notion that it reflects baroreflex modulation of cardiac ANS outflows (Rahman et al., 2011). Following the conventional view of LF, the ratio LF/HF is often interpreted as a measure of sympatho/vagal balance (Task Force, 1996), with greater LF/HF indicating dominance of the sympathetic activity, which, in turn is suspected to increase susceptibility to adverse cardiac outcomes (e.g. arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death; Chen et al., 2008). SampEn is a measure of the complexity (or irregularity) of the interbeat interval record, with lower entropy indicating suppressed ANS cardiac regulation. A highly regular record (e.g. indicating failure of the ANS) will result in a computed SampEn value close to zero while a highly irregular record will have a value close to 2. Previous studies have shown that low heart rate entropy is associated with onset of adverse cardiac events in various populations and, conversely, that complexity increases with physical resistance training in healthy men (Huikuri et al., 2009). We note that while the physiological and clinical significance of the various HRV measures remain subjects of ongoing research, the focus of this study is whether inhalation exposure to waterpipe smoke interferes with the cardiac ANS.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Thirty-three participants recruited in 2010–2011 in Richmond VA provided informed consent and attended at least one session in this Virginia Commonwealth University IRB-approved study. One participant was discontinued for high blood pressure at the beginning of a session. The remaining 32 participants (16 men, 22 non-White) were healthy, aged 18–50 years (M = 21.6 years, SD = 2.7), reported smoking tobacco using a waterpipe at least four times per month (M = 11.4, SD = 10.9) for the past six months (M = 2.2 years, SD = 1.6). Regular use of cigarettes (> 5 cigarettes/day) for the past year was exclusionary, and eleven of the participants currently smoked cigarettes (on average 2 cigarettes/day for past 23.5 months; range: 1 per month to 5 per day). Exclusion criteria included a history of chronic health problems or psychiatric conditions, low or high blood pressure, regular use of prescription medication (other than vitamins or birth control), and current pregnancy or breast feeding. Past month use (via self-report or positive urine test) of cocaine, opioids, benzodiazepines, and methamphetamine was exclusionary. Individuals who reported using marijuana more than five days or alcohol more than twenty days in the past thirty days were also excluded. All participants agreed to abstain from tobacco/nicotine containing products and caffeine/caffeinated beverages for at least 12 hours prior to each of four required sessions.

2.2 Materials

The waterpipe used during each session consisted of a chrome body (43 cm) screwed into an acrylic base (24 cm; volume 1230 ml; www.myasaray.com) with 870 ml of water placed into the base. The glazed ceramic head (7.6 cm; five, 6 mm holes in bottom) was covered with a 9 cm×9 cm circular piece of aluminum foil that was perforated using a “screen pincher” that standardizes the number and size of the holes in the foil (see www.smoking-hookah.com). Tobacco was heated with quick-light charcoal disks (33 mm diameter; 6.2 g; Three Kings, Holland). The leather hose connecting the water bowl to the mouthpiece was fitted with topography measurement hardware (Shihadeh et al., 2012) and the wooden mouthpiece was capped with a sterile plastic tip (www.hookahcompany.com) for each session. During the tobacco condition participants smoked Tangiers (Melon Blend flavor; a tobacco-based product manufactured in the U.S.; see http://www.tangiers.us/) and during the tobacco-free session they smoked Soex (Sweet Melon flavor; a tobacco-free sugarcane-based product). We used “melon” to control for flavor preference and excluded all individuals who reported that “melon” was their preferred flavor. Thus, for all study participants, the flavor used in this study was a non-preferred one. The Tangiers brand of was chosen for comparability across sessions.

2.3 Study design and procedures

A total of four Latin-square ordered experimental sessions were scheduled. Two of these sessions involved use of a caffeinated waterpipe tobacco product (Cobb, 2012), and in order to avoid confounding caused by effects of caffeine on HRV, data from those two sessions were not included in the current analysis. Sessions occurred at least 48 hours apart, and lasted for approximately 3 hours.

On each session day, participants reported to the laboratory at a pre-determined time (time of day varied between subjects, but was constant within-subject) and their expired air CO was assessed as a measure of compliance with overnight tobacco abstinence criterion (CO < 10 ppm). A catheter was placed in a forearm vein and the session began with continuous, computerized measurement of physiological response (HR and blood pressure) during a 20-minute adaptation period followed by a 10-minute baseline period. An electrocardiogram (ECG) signal was recorded for 5 minutes during the baseline period.. Once the baseline period was complete, , expired air CO was measured, participants responded to subjective measures, and 15 ml of blood was sampled. Participants then began a 45-minute, double-blind waterpipe use period with puff topography monitored throughout. Prior to each session, laboratory staff with no participant contact packed the waterpipe head with 10 g of the day’s preparation and covered it in perforated foil (Blank et al., 2011; Shihadeh, 2003). Initially, a single quick-light charcoal disk was lit, and several (pre-weighed) ½ charcoal disks were made available that participants could add to the top of the head, ad libitum (15 participants added charcoal during at least 1 session; average weight of added charcoal was 2.7 g). After waterpipe smoking had begun, 15 ml blood samples were collected and subjective responses were recorded at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes. As subjective response is not a focus of this report, this measure is detailed elsewhere (Cobb, 2012). ECG signal recording began again approximately 7 minutes prior to the end of the smoking session (45 minutes) and continued for 15 minutes post smoking (i.e., 60 minutes after smoking had begun). Expired air CO was recorded at 50, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after waterpipe smoking had begun (or 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes post smoking). The session terminated 5 minutes after the last assessment was completed, the catheter removed, and if necessary, another session was scheduled.

2.4 Outcome measures

Blood samples were centrifuged and plasma was frozen immediately at −70°C. For plasma nicotine, standard methods (see Breland et al., 2006) were used and include a limit of quantification (LOQ) of 2 ng/ml. Expired air CO was recorded using a breath CO monitor (Vitalograph, Lenaxa, KS). Average puff volume, total volume, number, and interpuff interval were measured for every smoking session using a waterpipe puff topography instrument (Shihadeh et al., 2005). Blood pressure was measured every 5 minutes with a automated inflatable cuff (Model 507E, Criticare Systems, Waukesha, WI), and ECG was measured with a second device (Model 507E, Criticare Systems, Waukesha, WI) using a three-lead system (leads placed under the right and left clavicle and under left lowest rib) and sampled at 300 Hz. Interbeat interval (IBI) series were generated for the five minute period prior to the first blood sample (“baseline”), the last five minutes of the 45-minute smoking session (“end”), and the five minute period starting 10 minutes after the end of the smoking session (“15 min”).

2.5 Statistical analysis

For plasma nicotine, results below the LOQ (2 ng/ml) were replaced with 2 ng/ml. For HRV, IBI series were derived from the ECG and were hand corrected for artifacts and ectopic beats using QRS Tool software (www.psychofizz.org; Allen et al., 2007). Absolute power in LF (0.04–0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15–0.40 Hz) frequency bands was found by computing the power density spectrum by FFT (Welch’s periodgram spectral estimation method) performed on the IBI series. SampEn was computed using the sampenc.m open source code available at PhysioNet (Goldberger et al., 2000). Epoch length (m) and tolerance (r) were set to values of 2 and 20%. To check for programming errors, LF, HF, and SampEn were also calculated for a limited number of interbeat interval records using the Kubios HRV analysis software 2.0 (The Biomedical Signal and Medical Imaging Analysis Group, University of Kuopio, Finland; http://kubios.uku.fi/KubiosHRV/).

All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (V19). The average of the value before and after was used to impute missing data. Data for HRV and expired air CO were complete for only 29 participants. Blood pressure analyses were limited to those participants with available HRV results. To simplify reporting time course data for plasma nicotine and expired air CO were converted to peak change scores (i.e., baseline value subtracted from all subsequent values and then the highest value observed is the peak; note that time course analysis did not differ in outcomes from those obtained using peak change). Peak change scores, puff topography, and HRV data were analyzed by paired t-tests.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Plasma nicotine/expired air CO exposure and puff topography

Table 1 shows the mean plasma nicotine, expired air CO, and puff topography data for the tobacco and tobacco-free conditions. As can be seen, plasma nicotine levels were elevated in the tobacco condition only, and significantly greater expired air CO levels were observed in the tobacco-free condition (p<0.01). For the tobacco condition, peak plasma nicotine and peak CO were highly correlated (N=29; r=0.751, p<0.01). Peak plasma nicotine concentrations were also compared between waterpipe smokers who currently smoked cigarettes (N=11) and those with no cigarette smoking history (N=16). While peak concentrations were higher among dual smokers (10.9±8.5 ng/ml) compared to waterpipe only smokers (5.9±8.1 ng/ml), an independent samples t-test and time course (mixed repeated measures ANOVA) did not support an effect of concurrent cigarette smoking on nicotine uptake (n.s.). Results for puff topography indicated that during the tobacco-free condition, on average, participants inhaled significantly larger total volume and took larger puffs (p<0.01), but there was no difference in the number of puffs between conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean (SD) puff topography and blood-level exposure.

| Tobacco | Tobacco-free | |

|---|---|---|

| Peak change from baseline | ||

| Plasma nicotine (ng/ml; N=32) | 7.8 (8.0) | 0.0 (0.0)* |

| Expired air CO (ppm; N=29) | 11.8 (7.7) | 30.9 (19.0)* |

| Topography (N=32) | ||

| Total smoke volume (l) | 31 (22) | 57 (34)* |

| Puffs drawn | 95 (115) | 95 (58) |

| Mean puff volume (ml) | 423 (250) | 683 (328)* |

| Mean interpuff interval (s) | 45 (34) | 35 (22)* |

| Mean puff duration (s) | 2.3 (0.9) | 3.5 (2.0)* |

indicates 95% significance relative to tobacco case; all significant differences exhibited p<0.01.

3.2 Heart rate variability

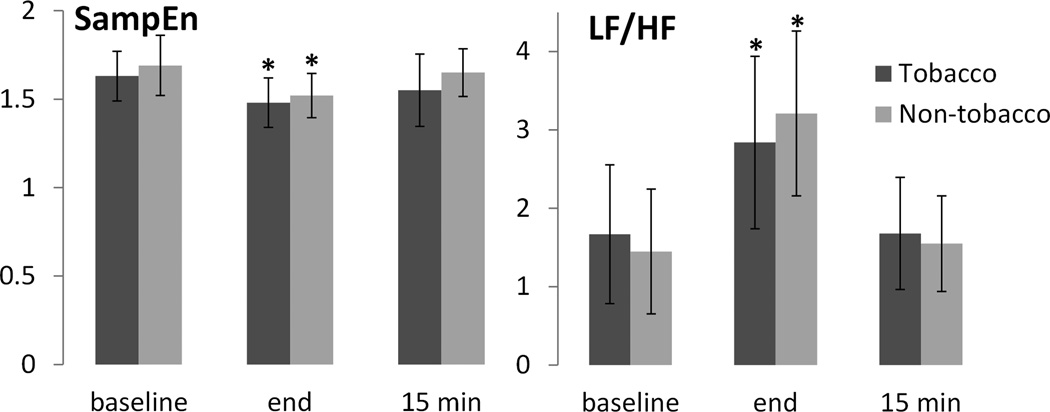

Results for HRV parameters are provided in Table 2 and Figure 2. Relative to baseline, LF and LF/HF increased significantly for both tobacco-based and tobacco-free waterpipe products by the end of the 45-minute smoking session, and recovered to baseline levels 15 minutes post-smoking (all p<0.01). HF did not change significantly by condition or time. SampEn decreased significantly by the end of the smoking session for both waterpipe product conditions (p<0.01), and recovered to near baseline values after 15 minutes. Blood pressure and heart rate increased (p<0.01) for the tobacco condition only.

Table 2.

Mean (SD) heart rate variability parameters for tobacco-based and tobacco-free products pre- and post-smoking.

| Tobacco Baseline |

End | 15 min | Tobacco-free Baseline |

End | 15 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (1/min) | 70.6 (8.6) | 75.5 (9.3)* | 72.2 (9.4) | 72.8 (8.2) | 71.5 (9.6) | 68.1 (8.7)* |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 63.7 (5.9) | 70.0 (7.4)* | 67.7 (6.3)* | 63.8 (6.4) | 64.3 (7.8) | 62.9 (8.1) |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 115.7 (11.3) | 120.4 (12.4) | 121.1 (12.4)* | 118.6 (9.2) | 117.6 (11.4) | 117.0 (13.3) |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 84.0 (7.3) | 89.3 (7.6)* | 89.4 (9.2)* | 83.7 (7.5) | 85.1 (8.5) | 82.9 (9.4) |

| LF (ms2) | 1400 (1420) | 2420 (2190)* | 1190 (1170) | 1330 (1170) | 3570 (2800)* | 1610 (1360) |

| HF(ms2) | 1270 (1790) | 1230 (1250) | 1140 (1350) | 1410 (2080) | 1690 (2420) | 1400 (1230) |

| LF/HF | 1.67 (1.77) | 2.84 (2.20)* | 1.68 (1.43) | 1.45 (1.59) | 3.21 (2.10)* | 1.55 (1.22) |

| SampEn | 1.63 (0.28) | 1.48 (0.28)* | 1.55 (0.41) | 1.69 (0.34) | 1.52 (0.25)* | 1.65 (0.27) |

Asterisk (*) indicates p<0.01 relative to baseline condition.

Note: N=29 for all outcomes except for mean arterial pressure (N=28).

Figure 2.

Mean HRV parameters at baseline, end of smoking session, and 15 minutes post-smoking. Error bars indicate ±SD. Asterisk (*) indicates p<0.01 relative to baseline condition. N=29.

4. DISCUSSION

Acute and/or chronic inhalation of airborne particle pollutants is widely recognized as a factor in cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality. Central hypotheses in the pathophysiology of airborne particulate matter-related cardiovascular disease include instigation of proinflammatory responses, alterations in systemic ANS activity, and direct effects of particulate matter constituents on airway receptors and in the systemic circulation (Brook et al., 2010; Routledge et al., 2006). These effects may occur on timescales of minutes following exposure episodes. While acute exposure to tobacco smoke has been shown to elicit almost immediate, temporary changes in HRV (Hayano et al., 1990; Karakaya et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2005), presumably due to the direct action of nicotine, it is also plausible that, like air pollution, tobacco smoke aerosols induce HRV effects unrelated to nicotine.Wolfram et al. (2003), for example, showed that a single waterpipe use session results in elevated marker of oxidative stress (8-epi-PGF! !) immediately after smoking; oxidative stress, in turn, leads to compromised cardiac ANS (Brook et al., 2010).

This study was undertaken to investigate toxicant exposure and acute effects of a single 45-minute waterpipe use session on autonomic regulation of the heart as assessed by changes in HRV pre- and post-smoking. The role of nicotine was also investigated by including a condition where users smoked a flavor-matched, nicotine-free waterpipe product. Waterpipe smoking caused acute changes in HRV characterized by an increase in LF/HF shortly after smoking, with recovery to baseline levels 15–20 minutes post-smoking. These findings are consistent with the three previous studies documenting acute effects of smoking a single cigarette (Hayano et al., 1990; Karakaya et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2005). Those studies showed an increase in LF/HF after smoking a single cigarette, with recovery to the pre-smoking LF/HF levels 10 to 20 minutes after smoking cessation. All demonstrated an increase in LF power, though Hayano et al. (1990) and Kobayshi et al. (2005) also found a transient decrease in HF power. In this study, the effect on LF/HF was through a large transient elevation in LF found in almost all of the smoking sessions, likely reflecting baroreflex-mediated changes in cardiovagal and sympathetic outflows (Rahman et al., 2011). Similarly, SampEn showed a temporary decrease and recovery to baseline, indicating a transient suppression of HRV associated with smoking. Interestingly, acute changes in HRV were independent of product tobacco content and nicotine delivery to the participant, although heart rate and blood pressure increased only with nicotine exposure.

A limitation of this study is that the “end” condition included active smoking, and therefore a potentially altered breathing rhythm. While breathing rhythm can alter HF HRV via respiratory sinus arrhythmia, it is unlikely that this factor affected the results of this study because puffing was infrequent during the last 5 minutes of the smoking session (median = 7 puffs), and there was no change in HF (the respiratory frequency band) at any of the three times. Further, we found no difference in changes in HRV for smoking sessions in which 2 or fewer puffs were drawn in the last 5 minutes compared to those for which more than two had been drawn.

During the current study, HR was increased when participants smoked the tobacco-containing product but not the tobacco-free waterpipe preparation (see Table 2), consistent with what is known about the effects of nicotine. This finding was similar to that observed in another placebo-controlled examination by Blank et al. (2011) that involved two double-blind counterbalanced sessions in which participants smoked their preferred flavor and brand of waterpipe tobacco (active) or a flavor matched non-tobacco preparation (placebo) for 45 minutes or longer. At the conclusion of the smoking period, the mean nicotine concentration during the placebo condition was 2.1 ng/ml (SD=0.0; note that 2 ng/ml is the limit of quantification of the assay), and during the active tobacco condition was 5.6 ng/ml (SD=4.3). During the current study at the conclusion of smoking, the mean nicotine level was 2.0 ng/ml (SD=0.0) for tobacco-free and 8.5 ng/ml (SD=6.6) for the tobacco condition. During both studies reliable increases in HR were observed during the active or tobacco-containing conditions but not during the placebo/tobacco-free condition. This pattern of results is consistent with HR increases being mediated by tobacco-delivered nicotine and not, for example, by CO exposure or the act of waterpipe smoking.

Important differences between the above mentioned placebo-controlled waterpipe study (Blank et al., 2011) and the current study are related to puff topography and CO exposure. For the previous examination, there were no differences in topography or for measures of CO by condition. However, results for puff topography and expired air CO did differ between conditions in the current study (see Table 1), with a significantly smaller mean total volume and mean puff volume during the tobacco condition compared to the tobacco-free condition. As total smoke volume was positively correlated with peak expired air CO during both conditions (r=0.52–0.66; N=29, p<0.01), the larger smoke volumes observed during the tobacco-free condition may explain the higher CO concentrations compared to the tobacco condition. Compensation or a change in smoking behavior to adjust to the mainstream smoke nicotine yield has been observed among cigarette smokers (Baldinger et al., 1995), and may also be driving the differences in puff topography observed in this study. Interestingly, mean total volume for the previous placebo controlled study (Placebo=56 l, Active=57 l; Blank et al., 2011) more resembled the tobacco-free condition (57 l) than the tobacco condition (31 l) of the current study. Mean plasma nicotine concentration also was 2.9 ng/ml higher during the tobacco condition at the conclusion of smoking compared to the active condition (Blank et al., 2011). With similar methodology between studies, except for the use of a participant’s usual brand for the tobacco-containing condition by Blank et al. (2011), the reduced total smoke consumed and increased nicotine exposure during the tobacco condition compared to the tobacco-free condition suggests that participants in this study reduced their smoked volume in order to reduce nicotine content. Parametrically manipulating waterpipe tobacco nicotine content/delivery in future studies may help resolve this issue.

Another clinical laboratory study of waterpipe tobacco smoking in 16 individuals who smoked at waterpipe for 30–60 minutes also observed substantial nicotine delivery during waterpipe smoking (average boost=11.7 ng/ml; Jacob et al., 2011). Interestingly, when participants were stratified by cigarette smoking status, nicotine concentrations were significantly greater among dual cigarette and waterpipe smokers (N=13; 24.8 ng/ml) compared to waterpipe only smokers (N=3; 8.4 ng/ml; Jacob et al., 2011). While peak plasma nicotine concentrations were higher among dual cigarette and waterpipe smokers in the current study, these concentrations were not significantly different from waterpipe only smokers. Importantly, sample size may be an important issue for both of these comparisons, and future research is needed to compare waterpipe smoking behavior among individuals with different tobacco smoking histories.

Our current findings also underscore previous work demonstrating that – contrary to advertising messages – tobacco-free or “herbal” waterpipe products deliver nearly identical quantities of a variety of toxicants associated with cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and cancer relative to tobacco-based products (Shihadeh et al., 2012). They also indicate that – at least in the case of waterpipe smoking – nicotine does not alone account for smoking-mediated changes in autonomic regulation of the cardiac cycle. In summary, smoking a waterpipe, with or without nicotine, results in acute dysfunction of cardiac regulation. While temporary autonomic dysfunction may destabilize vascular plaque or trigger cardiac arrhythmias (Brook et al., 2004), there is insufficient data in the literature to definitively relate transient dysfunction to specific long-term health consequences in waterpipe users.

5. CONCLUSIONS

A single waterpipe use session leads to measurable transient dysfunction in cardiac autonomic regulation, and suggests an increased risk of adverse cardiac events in users. Cardiac regulation is compromised with both tobacco-based and tobacco-free “herbal” waterpipe products, and therefore effects on HRV cannot be ascribed to effects of nicotine, although other known effects of nicotine (increase in HR) were observed only when participants smoked the nicotine-containing products. In addition to eliciting similar compromise of autonomic function, use of the tobacco-free waterpipe product also led to significantly higher exposure to CO and smoke, further underscoring the need for regulation of waterpipe products and their marketing as reduced harm alternatives. In addition, this study suggests that waterpipe smokers may titrate their smoke inhalation in response to available nicotine content in the product smoked. These findings support the growing body of research that waterpipe smoking is harmful and deserving of continued investigation to prevent associated adverse health consequences.

Highlights.

-

! !

Waterpipe smoking acutely suppresses heart rate variability and increases BP

-

! !

Herbal products exert similar effects on heart rate variability as tobacco products

-

! !

Herbal products result in no nicotine, but similar CO exposure to tobacco products

-

! !

Users draw larger puffs with herbal products, suggesting nicotine compensation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Mr. Ezzat Jaroudi, M.Eng. of the AUB for programming the data acquisition device, and Barbara Kilgalen, R.N., and Janet Austin, M.S. of VCU for their diligent efforts on data collection and management. Some of the data presented here were presented at the 73rd annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, and are part of a doctoral dissertation completed by Caroline O. Cobb at Virginia Commonwealth University.

FUNDING

This work is supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants R01CA120142, R01DA025659), and F31DA028102.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- Allen JJB, Chambers AS, Towers DN. The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: A pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almerie MQ, Matar HE, Salam M, Morad A, Abdulaal M, Koudsi A, Maziak W. Cigarettes and waterpipe smoking among medical students in Syria: a cross-sectional study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1085–1091. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mutairi SS, Shihab-Eldeen AA, Mojminiyi OA, Anwar AA. Comparative analysis of the effects of hubble-bubble (Sheesha) and cigarette smoking on respiratory and metabolic parameters in hubble-bubble and cigarette smokers. Respirology. 2006;11:449–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azab M, Khabour OF, Alkaraki AK, Eissenberg T, AlZoubi KH, Primack BA. Waterpipe tobacco smoking among university students in jordan. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:606–612. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldinger B, Hasenfratz M, Battig K. Effects of smoking abstinence and nicotine abstinence on heart rate, activity and cigarette craving under field conditions. Hum Psychopharm. 1995;10:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Blank MD, Cobb CO, Kilgalen B, Austin J, Weaver MF, Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T. Acute effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking: a double-blind, placebo-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland AB, Kleykamp BA, Eissenberg T. Clinical laboratory evaluation of potential reduced exposure products for smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:727–738. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC, Jr, Whitsel L, Kaufman JD. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–2378. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith S, Tager I. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease. A statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Chow D, Chiamvimonvat N, Glatter KA, Li N, He Y, Pinkerton KE, Bonham AC. Short-term secondhand smoke exposure decreases heart rate variability and increases arrhythmia susceptibility in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H632–H639. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91535.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb CO. (Doctoral dissertation) Virginia Commonwealth University; 2012. Evaluating the acute effects of caffeinated waterpipe tobacco in waterpipe users. [Google Scholar]

- Combrink A, Irwin N, Laudin G, Naidoo K, Plagerson S, Mathee A. High prevalence of hookah smoking among secondary school students in a disadvantaged community in Johannesburg. SAMJ. 2010;100:297–299. doi: 10.7196/samj.3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher N, Saleh R, Jaroudi E, Sheheitli H, Badr T, Sepetdjian E, Al Rashidi M, Saliba N, Shihadeh A. Comparison of carcinogen, carbon monoxide, and ultrafine particle emissions from narghile waterpipe and cigarette smoking: Sidestream smoke measurements and assessment of second-hand smoke emission factors. Atmospheric Environment. 2010;44:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker JM, Crow RS, Folsom AR, Hannan PJ, Liao D, Swenne CA, Schouten EG. Low heart rate variability in a 2-minute rhythm strip predicts risk of coronary heart disease and mortality from several causes: The ARIC study. Circulation. 2000;102:1239–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD. Effects of active and passive tobacco cigarette smoking on heart rate variability. International Journal of Cardiology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.140. in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Goldberger AL, Amaral LAN, Glass L, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov PC, Mark RG, Mietus JE, Moody GB, Peng C-K, Stanley HE. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation. 2000;101(23):e215–e220. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.23.e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Ayna D. Smoking among college students in the United States: a review of the literature. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(3):244–249. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.589419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano J, Yamada M, Sakakibara Y, Fujinami T, Yokoyama K, Watanabe Y, Takata K. Short- and long-term effects of cigarette smoking on heart rate variability. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huikuri HV, Perkiömäki JS, Maestri R, Pinna GD. Clinical impact of evaluation of cardiovascular control by novel methods of heart rate dynamics. Phil Trans R Soc A. 2009;367:1223–1238. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob P, III, Raddaha AHA, Dempsey D, Havel C, Peng M, Yu L, Benowitz NL. Nicotine, carbon monoxide, and carcinogen exposure after a single use of a waterpipe. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2345–2345. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PD, Cortes R, Engholm G, Kremers S, Gislum M. Waterpipe use predicts progression to regular cigarette smoking among danish youth. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1245–1261. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya O, Barutcu I, Kaya D, Esen AM, Saglam M, Melek M, Onrat E, Turkmen M, Esen OB, Kaymaz C. Acute effect of cigarette smoking on heart rate variability. Angiology. 2007;58:620–624. doi: 10.1177/0003319706294555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katurji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhalation Toxicol. 2010;22:1101–1109. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.524265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khabour OF, Alsatari ES, Azab M, Alzoubi KH, Sadiq MF. Assessment of genotoxicity of waterpipe and cigarette smoking in lymphocytes using the sister-chromatid exchange assay: a comparative study. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2011;52:224–228. doi: 10.1002/em.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi F, Watanabe T, Akamatsu Y, Furui H, Tomita T, Ohashi R, Hayano J. Acute effects of cigarette smoking on the heart rate variability of taxi drivers during work. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31:360–366. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41:34–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J, Paek D, Cho S, Min KB. Exposure to environmental carbon monoxide may have a greater negative effect on cardiac autonomic function in people with metabolic syndrome. Science of the Total Environment. 2009;407:4807–4811. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monn C, Kindler P, Meile A, Brändli O. Ultrafine particle emissions from waterpipes. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:390–393. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwayhid IA, Yamout B, Azar G, Al Kouatly KM. Narghile (hubble-bubble) smoking, low birth weight, and other pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:375–383. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzer B, Sepetdjian E, Saliba N, Shihadeh A. Charcoal emissions as a source of CO and carcinogenic PAH in mainstream narghile waterpipe smoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2991–2995. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwayhid IA, Yamout B, Azar G, Kambris MA. Narghile (hubble-bubble) smoking, low birth weight, and other pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(4):375–383. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pärna K, Usin J, Ringmets I. Cigarette and waterpipe smoking among adolescents in Estonia. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Pope CA. Cardiopulmonary mortality and air pollution. Lancet. 2002;360:1184–1185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11289-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Shensa A, Kim KH, Carroll M, Hoban M, Leino EV, Eissenberg T, Dachille K, Fine MJ. Waterpipe smoking among U.S. university students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts076. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raad D, Gaddam S, Schunemann HJ, Irani J, Jaoude PA, Honeine R, Akl EA. Effects of water-pipe smoking on lung function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2011;139:764–774. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman F, Pechnik S, Gross D, Sewell L, Goldstein D. Low frequency power of heart rate variability reflects baroreflex function, not cardiac sympathetic innervation. Clin Auton Res. 2001;21:133–141. doi: 10.1007/s10286-010-0098-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman JS, Moorman JR. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H2039–H2049. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riojas-Rodríguez H, Escamilla-Cejudo JA, González-Hermosillo JA, Téllez-Rojo MM, Vallejo M, Santos-Burgoa C. Personal PM2.5 and CO exposures and heart rate variability in subjects with known ischemic heart disease in Mexico City. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2006;6:131–137. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Ferreira Rivero DH, Sassaki C, Lorenzi-Filho G, Nascimento Saldiva PH. PM(2.5) induces acute electrocardiographic alterations in healthy rats. Environ Res. 2005;99:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskin J, Aveyard P. Canadian and English students' beliefs about waterpipe smoking: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge H, Manney S, Harrison R, Ayres J, Townend J. Effect of inhaled sulphur dioxide and carbon particles on heart rate variability and markers of inflammation and coagulation in human subjects. Heart. 2006;92:220–227. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.051672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saade G, Warren CW, Jones NR, Mokdad A. Tobacco use and cessation counseling among health professional: lebanon global health professions student survey 2005. Lebanese Medical Journal. 2009;57:243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert J, Bewersdorff J, Luch A, Schulz T. Waterpipe smoke: A considerable source of human exposure against furanic compounds. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2012;709:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert J, Hahn J, Dettbarn G, Seidel A, Luch A, Schulz TG. Mainstream smoke of the waterpipe: Does this environmental matrix reveal as significant source of toxic compounds? Toxicology Letters. 2011;205:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A. Investigation of the mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A, Antonis C, Azar SA. Portable low-resistance puff topography instrument for pulsating, high-flow smoking devices. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37:186–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03206414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A, Salman R, Jaroudi E, Saliba N, Sepetdjian E, Blank MD, Cobb CO, Eissenberg T. Does switching to a tobacco-free waterpipe product reduce toxicant intake? A crossover study comparing CO, NO, PAH, volatile aldehydes, “tar” and nicotine yields. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1494–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H, Larson MG, Venditti FJ, Manders ES, Evans JC, Feldman CL, Levy D. Impact of Reduced Heart Rate Variability on Risk for Cardiac Events the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1996;94:2850–2855. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Känel R, Carney R, Zhao S, Whooley M. Heart rate variability and biomarkers of systemic inflammation in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram RM, Chehne F, Oguogho A, Sinzinger H. Narghile (water pipe) smoking influences platelet function and (iso-)eicosanoids. Life Sci. 2003;74(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]