Highlights

► Novel ATP analogue ADP–MgF3− traps an AAA+ ATPase with its target σ54. ► MgF3−-dependent complex forms a highly homogenous population. ► MgF3−-dependent complex represents an early transcription intermediate state.

Keywords: AAA+ ATPase, Nucleotide analogue, Transcription, bEBP, PspF, σ54

Abstract

The widely distributed bacterial σ54-dependent transcription regulates pathogenicity and numerous adaptive responses in diverse bacteria. Formation of the σ54-dependent open promoter complex is a multi-step process driven by AAA+ ATPases. Non-hydrolysable nucleotide analogues are particularly suitable for studying such complexity by capturing various intermediate states along the energy coupling pathway. Here we report a novel ATP analogue, ADP–MgF3−, which traps an AAA+ ATPase with its target σ54. The MgF3−-dependent complex is highly homogeneous and functional assays suggest it may represent an early transcription intermediate state valuable for structural studies.

1. Introduction

The high-energy phosphoryl transfer reaction is a principle mechanism exploited by mechanochemical enzymes such as the AAA+ ATPases (ATPases associated with various cellular activities). The AAA+ ATPases convert the chemical energy released from ATP hydrolysis to the remodelling of a diverse array of their substrates, to achieve for example protein unfolding, membrane fusion, DNA repair and transcription activation [1,2]. However, this energy transfer process is transient. In order to capture the AAA+ ATPases and their substrates for kinetic and structural studies, nucleotide analogues are widely used. These analogues, in many cases, consist of an ADP and a metallo-halide (e.g., AlFx, which occupies the γ-phosphate position within the ATP catalytic site) and are reported to represent different ATP states (AMP–AlFx and ADP–BeF3– for the ATP ground state and ADP–AlFx for the ATP transition state). Being the most frequently used γ-phosphate analogue, the AlFx moiety shows complexity in binding to the catalytic site. Schlichting et al. [3] surveyed the majority of the AlFx-containing crystal structures and demonstrated that the pH of the crystallographic experiment determined whether AlF3 or AlF4− was present in the crystal (thus abbreviated as AlFx in this paper). The AlF3 moiety adopts a trigonal bipyramidal arrangement with the axial coordination sites being occupied by oxygens from the β-phosphate and hydrolytic water, which is thought to closely mimic the γ-phosphate at the point of hydrolysis in geometry [4]. The AlF4− moiety adopts an octahedral arrangement with a net negative charge, complementary to the transition state γ-phosphate [4]. The fact that both AlFx species are found in the crystal structures suggests the catalytic site has enough flexibility to accommodate either without much reconfiguration and energy loss [3].

Vincent et al. reported a high-affinity dimeric complex formation between the RhoA GTPase and the p190 RhoGAP (Rho GTPase-activating protein) in a fluoride- and magnesium-dependent manner but an aluminium- and GDP-independent manner [5]. To investigate whether the same effect can be observed on AAA+ ATPases and their substrates, we employed a bacterial enhancer binding protein (bEBP) called the Escherichia coli phage shock protein F (PspF) – a Clade 6 hexameric AAA+ ATPase for this study [6]. PspF or its AAA+ domain alone (residues 1–275, PspF1–275) can activate the psp operon (pspABCDE and pspG) [7] by reorganising the Eσ54–DNA complex through PspF surface-exposed loops in a nucleotide-dependent manner. Recently, the Cryo-EM contour structure of a PspF1–275•Eσ54•ADP–AlFx complex has been resolved [8]. However, the high-resolution hexameric crystal structure of PspF is yet to be obtained, partially due to the interference from precipitation arising from high concentrations of AlCl3 used.

Here, we report an MgF3−-dependent complex formation between the ADP-bound PspF1–275 and σ54. We demonstrated that this novel MgF3−-dependent complex was more homogeneous than the previously described complexes with AlFx and may represent an intermediate state early along the activation pathway. We propose that MgF3− will serve as a new reagent to obtain high-resolution structural information on co-complexes of some AAA+ ATPases with their remodelling targets.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein expression

E. coli PspF1–275 was purified as previously described [9]. Klebsiella pneumonia σ54 was purified as previously described [10].

2.2. Native gel mobility shift assay

Reactions were performed in 10 μl volumes containing 10 μM PspF1–275, 2.35 μM σ54, ±AlCl3, ±MgCl2, ±ADP and ±NaF in STA buffer (2.5 mM Tris–acetate pH 8.0, ±8 mM Mg–acetate, ±8 mM K–acetate, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 3.5% (w/v) PEG 8000) at 37 °C for 15 min. Complexes were analysed on 4% native gels.

2.3. Gel filtration

The trapped complexes with 20 μM PspF1–275 and 4.7 μM σ54 were formed after 15 min incubation with reagents at 37 °C and run with gel filtration buffer (20 mM Tri–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2) in a Superdex 200 Column (10/30, 24 ml, GE Healthcare) at room temperature.

2.4. In vitro RPO formation assay

The RPO formation assay was conducted as previously described [9]. Typically in 10 μl volumes, 4 μM PspF1–275, 100 nM holoenzyme (1:4 ratio of E: σ54), 4 mM dATP and 20 nM linear Sinorrhizobium meliloti nifH promoter probes (Sigma–Aldrich) were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min before the elongation mixture (0.5 mM dinucleotide primer UpG, 0.2 μCi/μl [α-32P GTP] (3000 Ci/mmol) and 0.2 mg/ml heparin) was added for another 10 min incubation. Reactions were quenched by addition of 4 μl formamide stop dye and run on a sequencing gel.

3. Results

3.1. The Mg2+-promoted PspF1–275–σ54 complex requires ADP but not Al3+

In the presence of the ATP transition state analogue ADP–AlFx, the PspF surface-exposed L1 loops extend to stably engage σ54 [11]. The resulting PspF1–275•σ54•ADP–AlFx trapped species represents a sub-complex of one of the intermediate states en route to open complex formation (RPO) [12] to support transcription initiation by making the start site available [13]. However, heterogeneity is often observed in the population of ADP-AlFx trapped complexes (Fig. 1 lane 4), which can lead to potential complications in mass spectroscopic analyses and crystallography. Higashijima et al. have shown that at high F− concentrations, Mg2+ can replace Al3+ in transforming the G protein α subunit into a more active state, possibly by associating with three F− ions to mimic the γ-phosphate of GTP [14]. In an attempt to obtain a more homogeneous population of PspF1–275–σ54 trapped complexes, possibly with new geometrical and functional features, we performed the trapping experiment by in situ formation of MgF3− in the absence and presence of nucleotides.

Fig. 1.

PspF1–275 forms nucleotide- and MgF3−-dependent trapped complexes with σ54. The STA (+ 8 mM Mg2+) buffer has been routinely used in various native gel shift assays and transcription activation assays and contains 2.5 mM Tris–acetate pH 8.0, 8 mM Mg2+–acetate, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 3.5% PEG 8000. To assess whether the trapped complex formation was dependent on the intrinsic Mg2+ ions, the STA (−8 mM Mg2+) buffer was used in which the 8 mM Mg2+–acetate was replaced by 8 mM K+–acetate.

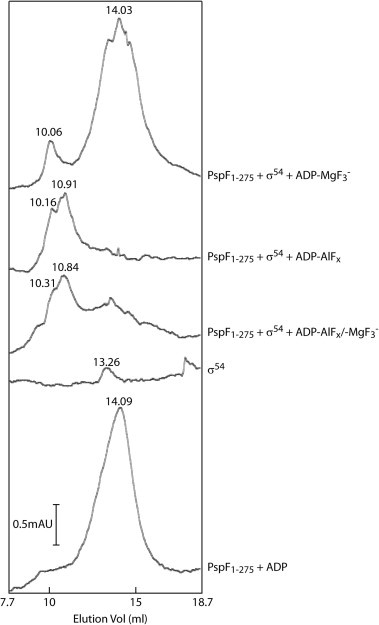

The trapping reaction buffer (STA buffer), which has routinely been used in various binding and transcription activation assays [9], contains 8 mM Mg2+–acetate. We initially assessed whether the intrinsic Mg2+ concentration from the reaction buffer was sufficient to support the formation of MgF3− moieties. Indeed, without any added Al3+, a more homogeneous population of Mg2+-promoted complexes was observed, whose formation was absolutely dependent on the presence of ADP (Fig. 1 lanes 5 and 6) and NaF (Fig. 1 lane 11). Addition of further Mg2+ ions to the PspF1–275–σ54 interaction assay did not seem to increase the yield of complexes, even though the concentrations of PspF1–275 and σ54 were not limiting (Fig. 1 compare lane 8 with lane 6). When the Mg2+ ions were removed from the STA buffer, the PspF1–275–σ54 complex formation was completely abolished (Fig. 1 lane 12) but restored once the Mg2+ ions were added back (Fig. 1 lane 10), further confirming the Mg2+-dependent nature of this newly trapped complex. The gel filtration data (Fig. 2) demonstrated that the ADP–MgF3−-dependent complex eluted as a single homogenous peak (at 10.06 ml) before the doubly peaked ADP–AlFx-dependent complexes (at 10.16/10.91 ml), suggesting a different intermediate state is likely to be represented by the ADP–MgF3−-dependent complex.

Fig. 2.

Gel filtration of the ADP–AlFx/–MgF3− dependent trapped complexes at room temperature.

The above observations suggest that the AlFx-dependent trapped complexes formed in the presence of Mg2+ ions are likely to be a mixture of PspF1–275•σ54•ADP–AlFx/–MgF3− with ADP–AlFx species dominating.

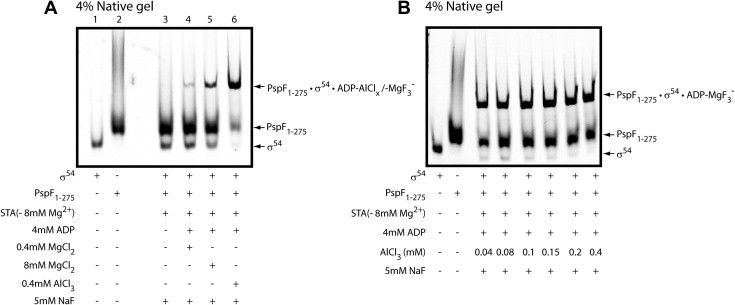

3.2. ADP–AlFx stabilises the PspF1–275–σ54 complex more strongly than does ADP–MgF3−

Since trapped complexes formed in STA buffer contain a mixture of PspF1–275•σ54•ADP–AlFx/–MgF3− due to the presence of both Mg2+ and Al3+ ions in the reaction, we examined whether or not the AlFx-dependent complexes could form in the absence of Mg2+ ions. As shown in Fig. 3A, adding NaF and Al3+ ions to the Mg2+–acetate free STA buffer shifted nearly all the σ54 into the trapped complex (Fig. 3A lane 6). The addition of 0.4mM Mg2+ ions (same concentration as Al3+ ions) or a 20-fold higher concentration of Mg2+ ions yielded 16% and 37% ADP–MgF3− trapped complexes compared to the Al3+-dependent assays (Fig. 3A compare lanes 4 and 5 with 6). Furthermore, a titration experiment revealed that a relatively low concentration of the Al3+ ions (0.04 mM) was required to form the AlFx-dependent complexes, much lower than the 0.4 mM routinely used (Fig. 3B). The above observations suggest that although both Al3+ and Mg2+ ions can form the ADP-dependent trapped complexes independently of one another’s presence, the Al3+ ions are far more efficient at promoting the complex formation.

Fig. 3.

(A) Al3+ ions are more efficient at promoting the trapped complex formation. (B) Titration of the amount of Al3+ ions required for trapped complex formation.

3.3. ADP–MgF3− is a functional analogue of ADP–BeF3– in RPO formation

Burrows et al. [13] devised a short primed RNA (spRNA) synthesis assay and demonstrated that the putative transition state ADP–AlFx complex could reorganise Eσ54 to a near open complex state on a pre-opened linear DNA probe (the S. meliloti nifH promoter with the non-template ‘melted’ from −10 to −1). However, the ground state ADP–BeF3– complex failed to do so [13]. Here we employed the spRNA assay to assess whether the MgF3−-dependent complexes are transcriptionally active and/or carry any functional similarities to either ADP–AlFx or ADP–BeF3– dependent complexes.

In the presence of a dinucleotide primer UpG and radio-labelled GTP, abortive tetra-nucleotides UpGpGpG are generated on the linear nifH promoter by preventing Eσ54 from transcribing beyond the +3 site. The amount of UpGpGpG formed reflects the amount of RPO-like activity in the presence of ADP-metal fluorides. Consistent with the previous data, the ADP–AlFx dependent complex was able to generate an RPO-like activity from the pre-melted DNA probe (Fig. 4). However, the ADP–MgF3−-dependent complex failed to yield RPO-like activity from any linear DNA probes used in this experiment (Fig. 4) – a similar functional phenotype was exhibited by the ADP–BeF3– dependent complexes [13]. We propose that MgF3− and BeF3– may (i) similarly change the organisation of the ATPase catalytic site and (ii) represent functional intermediate states of the AAA+ domain in ATP hydrolysis which form prior to the state created by the ADP–AlFx.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the ADP–AlFx and ADP–MgF3− dependent complexes in the RPO formation assay. The amount of abortive tetra-nucleotides (UpGpGpG) generated from this assay directly correlates with the amount of open complex formation. Three DNA sequences with mismatches on the non-template strand (thick curves in cartoons) were used: the homoduplex WT/WT, the early-melted −12−11/WT (mimicking the DNA conformation in the closed promoter complex), and the late-melted −10−1/WT (mimicking the DNA conformation in the open promoter complex).

4. Discussion

We have identified a new method dependent on the formation of MgF3− moieties, to stably trap an AAA+ ATPase PspF1–275 with its target substrate σ54. The MgF3−-dependent complexes can co-exist in solution with the AlFx-dependent complexes when both metal ions are present – a condition under which most of the previous biochemical, mass spectroscopic and crystallographic experiments were performed. This potential heterogeneity of complex formation with AlCl3 and NaF in the presence of Mg2+ is not readily detected given the AlFx functions more efficiently in trapping conditions, and so could have been easily overlooked. As a potential source of heterogeneity in protein conformation, the presence of MgF3− and AlFx may interfere with protein crystallisation. Based on the pH effect [3], we reason that the AlFx moiety under the trapping conditions in this work (pH 8.0) is more likely to assume a trigonal bipyromidal AlCl3 configuration than an octahedral AlF4− configuration. However, Xiaoxia et al. [15] argue that there is a dominant role of charge in selection of the best bound ATP analogues and thus the AlF4− moiety might be considered the better binding candidate species compared to AlCl3, as has been observed in other classes of ATP hydrolysing enzymes. Clearly, further detailed analyses and high resolution structural information are required to determine the precise ATP analogue species bound and roles of charge/geometry relationships in their binding to the bEBP class of ATPases.

Vincent et al. suggested that additional mechanistic roles could be assigned to the MgF3− moiety. Their observation of MgF3−-dependent GTPase–GAP complex formation in the absence of GDP challenges the widely held γ-phosphate mimicking role for MgF3− [5]. Our MgF3−-dependent trapping data revealed an absolute requirement for ADP for PspF1–275 to interact with σ54, suggesting that MgF3− in AAA+ ATPases is confined to function solely as a γ-phosphate mimick. We reason that in contrast to the relatively ‘simple’ GTP catalytic site between the GTPase–GAP heterodimer, the ATP catalytic sites at the hexameric interfaces of an AAA+ ATPase need to be precisely organised and selective for nucleotide analogues in order to productively coordinate the energy relay across subunits [16].

The MgF3− and BeF3– moieties as trapping reagents displayed similar phenotypic traits at the level of the PspF1–275 engaging its target. Both moieties are less efficient at promoting the PspF1–275–σ54 complex formation than is the AlFx moiety (14% by BeF3– and 16% by MgF3− in comparison to 100% by AlFx), and are unable to productively reorganise RPC to yield an RPO-like complex on a pre-opened DNA probe ([13] and this work). Graham et al. suggest that the geometry of these two moieties is different at the catalytic site, as BeF3– adopts a tetrahedral arrangement and MgF3− adopts a trigonal bipyromidal arrangement [4]. Thus, MgF3− and BeF3– in combination with ADP may represent slightly different intermediate early states of bound ATP prior to ATP hydrolysis. Clearly the MgF3−- and ADP-dependent PspF1–275–σ54 complex has novelty and is the first such complex reported for an AAA+ ATPase, with the potential to advance high-resolution structural studies between nucleotide-bound AAA+ ATPases and their targets in pre-hydrolysis state.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Project Grant (BB/J002828/1) to M.B. We thank Prof. G. Dodson and Dr. N. Joly for stimulating discussion and members of M.B. lab for their constructive comments and support.

References

- 1.Snider J., Houry W.A. AAA+ proteins: diversity in function, similarity in structure. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:72–77. doi: 10.1042/BST0360072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker P.A., Sallai L. The AAA+ superfamily – a myriad of motions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:641–652. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlichting I., Reinstein J. PH influences fluoride coordination number of the AlFx phosphoryl transfer transition state analog. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:721–723. doi: 10.1038/11485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham D.L., Lowe P.N., Grime G.W., Marsh M., Rittinger K., Smerdon S.J., Gamblin S.J., Eccleston J.F. MgF(3)(−) as a transition state analog of phosphoryl transfer. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:375–381. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincent S., Brouns M., Hart M.J., Settleman J. Evidence for distinct mechanisms of transition state stabilization of GTPases by fluoride. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2210–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erzberger J.P., Berger J.M. Evolutionary relationships and structural mechanisms of AAA+ proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:93–114. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joly N., Engl C., Jovanovic G., Huvet M., Toni T., Sheng X., Stumpf M.P., Buck M. Managing membrane stress: the phage shock protein (Psp) response, from molecular mechanisms to physiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010;34:797–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bose D., Pape T., Burrows P.C., Rappas M., Wigneshweraraj S.R., Buck M., Zhang X. Organization of an activator-bound RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang N., Joly N., Burrows P.C., Jovanovic M., Wigneshweraraj S.R., Buck M. The role of the conserved phenylalanine in the sigma54-interacting GAFTGA motif of bacterial enhancer binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5981–5992. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannon W.V., Gallegos M.T., Buck M. Isomerization of a binary sigma-promoter DNA complex by transcription activators. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:594–601. doi: 10.1038/76830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rappas M., Schumacher J., Niwa H., Buck M., Zhang X. Structural basis of the nucleotide driven conformational changes in the AAA+ domain of transcription activator PspF. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leach R.N., Gell C., Wigneshweraraj S., Buck M., Smith A., Stockley P.G. Mapping ATP-dependent activation at a sigma54 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33717–33726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burrows P.C., Joly N., Buck M. A prehydrolysis state of an AAA+ ATPase supports transcription activation of an enhancer-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:9376–9381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001188107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higashijima T., Ferguson K.M., Sternweis P.C., Ross E.M., Smigel M.D., Gilman A.G. The effect of activating ligands on the intrinsic fluorescence of guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:752–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiaoxia L., Marston J.P., Baxter N.J., Hounslow A.M., Yufen Z., Blackburn G.M., Cliff M.J., Waltho J.P. Prioritization of charge over geometry in transition state analogues of a dual specificity protein kinase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3989–3994. doi: 10.1021/ja1090035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joly N., Buck M. Engineered interfaces of an AAA+ ATPase reveal a new nucleotide-dependent coordination mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:15178–15186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]