Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common primary cancer arising from the kidney in adults, with clear cell carcinoma (ccRCC) representing ~75% of all RCCs. Increased expression of the hypoxia-induced factors HIF1α and HIF2α has been suggested as a pivotal step in ccRCC carcinogenesis, but this has not been thoroughly tested. Here we report that expression of a constitutively activated form of HIF2α (P405A, P530A and N851A, HIF2αM3) in the proximal tubules of mice is not sufficient to promote ccRCC by itself, nor does it enhance HIF1αM3 oncogenesis when co-expressed with constitutively active HIF1αM3. Neoplastic transformation in kidneys was not detected at up to 33 months of age, nor was increased expression of Ki67 (MKI67), γH2AX (H2AFX) or CD70 observed. Further, the genome-wide transcriptome of the transgenic kidneys does not resemble human ccRCC. We conclude that a constitutively active HIF2α is not sufficient to cause neoplastic transformation of proximal tubules, arguing against the idea that HIF2α activation is critical for ccRCC tumorigenesis.

Keywords: clear cell renal cell carcinoma, murine cancer model, kidney cancer, RNA-seq

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common primary cancer arising from the kidney in adults, with clear cell carcinoma (ccRCC) representing ~75% of all RCCs (1, 2). Loss of expression or mutation of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene is found in hereditary and most sporadic ccRCCs (1, 3). This suggests an etiological role for VHL gene loss in renal carcinogenesis. However, the exact pathway by which loss of VHL leads to ccRCC has not been elucidated. The best studied and likely the most important effect of VHL loss is the increased expression of the alpha subunits of hypoxia inducible factors 1 (HIF1α) and 2 (HIF2α) (4-6). Increased expression of these two transcription factors has been proposed as a key step in ccRCC carcinogenesis (4). HIF2α shares ~48% amino acid homology with HIF1α (7). Both HIF1α and HIF2α are regulated by prolyl hydroxylation at proline sites and by asparaginyl hydroxylation at an asparagine site under normoxic conditions (7), and each pairs with HIF1β and binds to Hypoxia Responsive Elements (HREs, 5′-RCGTG-3′) (7). HIF2α protein levels are increased and HIF2α is transcriptionally activated in VHL−/−renal carcinomas (8). Furthermore, elimination of HIF2α in RCC cell lines is sufficient to suppress VHL−/−tumor growth in xenograft models (9, 10). Tumor suppression by pVHL can be overridden by HIF2α but not HIF1α in tumor xenografts of cultured 786-0 cells (9, 11, 12). These data collectively suggest that HIF2α may be more oncogenic than HIF1α for tumor xenograft growth, although other data indicate that HIF1α is more oncogenic (13-18).

At present, few murine models that exhibit the pertinent features of human ccRCC exist. Human tumorgraft models of ccRCC have significant limitations, including the immunodeficient state of the animals (19). We recently reported a TRAnsgenic model of Cancer of the Kidney (TRACK) model which mimics early stage human ccRCC through expression of a triple mutant (P402A, P564A and N803A) human HIF1α construct (13). We have now employed the same kidney proximal tubule specific type 1 γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT or γGT) promoter (20, 21) to drive expression of a triple mutant (P405A, P530A and N851A), constitutively active HIF2α protein specifically in the proximal tubule cells (PTCs) to determine if this results in carcinogenesis. We show here that this triple mutant, HIF2α protein (HIF2αM3) is active, even under normoxic conditions. Transgenic mice that express this triple mutant, constitutively active HIF2α construct specifically in the kidney exhibit glycogen accumulation and hydropic degeneration, but no lipid deposition. We also do not observe renal cysts or disorganized proximal tubules resembling in situ carcinoma. We do not observe overexpression of molecular markers of cancer, e.g. Ki67, γH2AX, and CD70, in the kidneys of HIF2αM3 transgenic positive (TG+) mice. Furthermore, we analyzed entire transcriptomes of cells from the HIF2αM3 TG+ kidney cortex by Next Generation Sequencing/RNA-seq. The kidney cortex transcriptome of HIF2αM3 TG+ mice does not closely resemble that of human ccRCC, consistent with the lack of tumorigenesis in these mice.

Material and Methods

Plasmid Construction and Generation of Transgenic Mice

Mutated, constitutively active mouse HIF2α cDNA was created by site-directed mutagenesis (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) of conserved proline residues (proline 405, 530) and a conserved asparagine (asparagine 851) into alanine residues. The rat GGT promoter (−1930– +246) was amplified by PCR from a plasmid (21). The GGT promoter, mutated HIF2α, and beta-globin poly-A were cloned into pBlueScript and named γGT-HIF2α triple mutant (γ-HIF2αM3). A linearized XhoI-XbaI fragment (vector sequence removed) was injected into pronuclei of one-cell embryos (C57BL/6 × C57BL/6) at the WCMC Mouse Genetics Core. Southern Blot analysis was then performed (13). The γ-HIF2αM3 transgene was carried in the heterozygous state. The γ-HIF2αM3-1 and the γ-HIF2αM3-17 lines were mated with the TRACK mice to obtain γ-HIF1αM3;γ-HIF2αM3 double TG+ mice. Both γ-HIF1αM3 and γ-HIF2αM3 transgenes are carried in the heterozygous state in the double TG+ mice. All animal procedures were performed following guidelines of Research Animal Resource Center.

Tissue Dissection, Processing, Pathological Review, and Histology/Staining

Tissues were fixed, processed, sectioned, and H&E stained (13). Slides were reviewed in a blinded manner by Dr. Shevchuk, an experienced clinical pathologist specializing in human kidney cancer, and independently by a veterinary pathologist, Dr. Linda Johnson, from the Laboratory of Comparative Pathology, WCMC. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described (13). Antibodies used: HIF2α (100-122, Novus Biologicals); CA-IX (sc-25600, Santa Cruz); Glut-1 (ab14683, Abcam, Cambridge, MA); Ki67 (M7249, Dako, Denmark); and γH2AX (9718S, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Periodic Acid/Schiff (PAS) stain was performed on paraffin-embedded and cryo-preserved sections (13). Oil red O (ORO) staining was performed as described (13).

Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), Whole Genome RNA Sequencing, and Data Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using mini-RNAeasy columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was then performed (13). Total RNA from thin, outer slices of kidney cortex were used for whole genome sequencing. The complete transcriptomes of kidney cortex from 3 γ-HIF2αM3 18 month old TG+ male mice and 3 age matched wild type (WT) C57BL/6 male mice were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000 Sequencer. The reads were aligned to the mouse genome (NCBI37.55/MM9) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (22) in GobyWeb software (23). Comparisons of gene expression changes between γ-HIF2αM3 TG+ and WT male mice were performed using Differential Expression Analysis with Goby in the GobyWeb. Benjamini and Hochberg FDR adjustment (q-value) for t-test (t-test-BH-FDR-q-value) and Benjamini and Hochberg FDR adjustment (q-value) for Fisher exact test (fisher-exact-test-BH-FDR-q-value) were used to determine statistical significance. The data will be deposited in NIH databases upon acceptance for publication.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Student’s t test was used to determine the statistical significance of the γH2AX+ and Ki67+ cell number differences between TG+ and WT kidneys.

Results

Generation of transgenic mice that express mutated, constitutively active HIF2μ

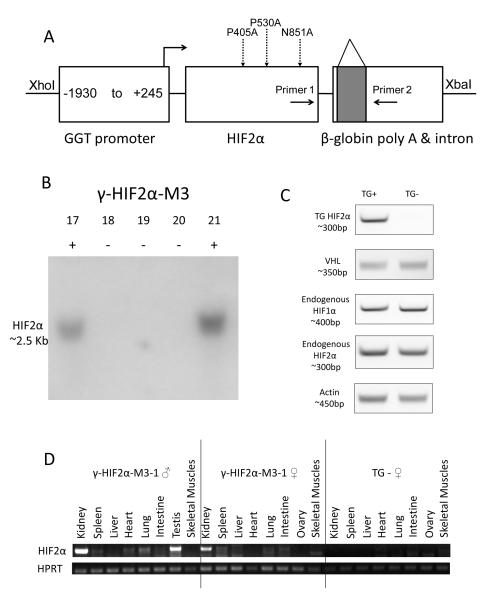

To examine the role of HIF2μ in ccRCC carcinogenesis we constructed a GGT-HIF2μ triple mutant plasmid (γ-HIF2μM3, Fig. 1A). After confirmation of activity in a cultured normal kidney proximal tubule cell line, a linearized γ-HIF2μM3 XbaI-XhoI fragment was used to generate γ-HIF2μM3 transgenic mice. A total of 10 out of 50 founder mice harbored the integrated target gene by Southern analysis (Fig. 1B, founders #17 to #21). Three lines (#21, #34 and #38) did not show germ line transmission. The other 7 lines were evaluated by RT-PCR, using a transgene specific primer pair (primers 1 and 2, Fig. 1A) for transgene mRNA levels in the kidney, spleen, liver, heart, lung, intestine, skeletal muscle, and testis/ovary. The triple mutant HIF2μ (γ-HIF2μM3) was expressed only in the kidneys of TG+ lines #1, #17, #27, #31 and #48 (Fig. 1C, TG+, #1 as an example). The transgene was not expressed in the other organs analyzed, except for low expression in the testis (Fig. 1D). VHL, endogenous HIF1μ, and endogenous HIF2μ mRNA levels were not changed in the kidneys of TG+ mice compared with the kidneys of transgenic negative (TG-) mice (Fig. 1C, TG-). All five TG+ founder lines, γ-HIF2μM3-1, γ-HIF2μM3-17, γ-HIF2μM3-27, γ-HIF2μM3-31 and γ-HIF2μM3-48, developed normally and could pass the transgene to offspring following a Mendelian pattern of inheritance. Since the GGT promoter is not active until about 3 weeks after birth (20, 21), we did not expect and did not observe any gross developmental abnormalities in the kidneys.

Figure 1. Generation of γ-HIF2μM3 transgenic mice.

A. Construction of the γ-HIF2μM3 plasmid. Only the fragment used to create the TG+ mice is shown. Three mutations (P405A, P530A and N851A), dashed arrows. An intron (shaded square) is included in the β-globin poly A. Primers 1 and 2 are used to amplify the transgene by RT-PCR. B. Southern Blot of the TG+ and TG-Founders. Only founder #17 to #21 mice are shown. Founders #17 and #21 are TG+, others shown are TG-. C. HIF2μ transgene, endogenous VHL, HIF1μ, and HIF2μ RT-PCR in kidneys of the γ-HIF2μM3-1 line. The HIF2μ transgene was only detected in the TG+ mice. Endogenous VHL, HIF1μ, and HIF2μ mRNAs are expressed at similar levels in TG+ and TG-mice. β-Actin, loading control. D. HIF2μ transgene RT-PCR in multiple organs of the γ-HIF2μM3-1 line mice. The HIF2μ transgene is detected specifically in the kidneys and testes of TG+ mice from the γ-HIF2μM3-1 line. No expression of the γ-HIF2μM3 transgene was detected in any organ of the TG-mouse. β-Actin, loading control.

HIF2μ and its target genes are upregulated in TG+ kidneys

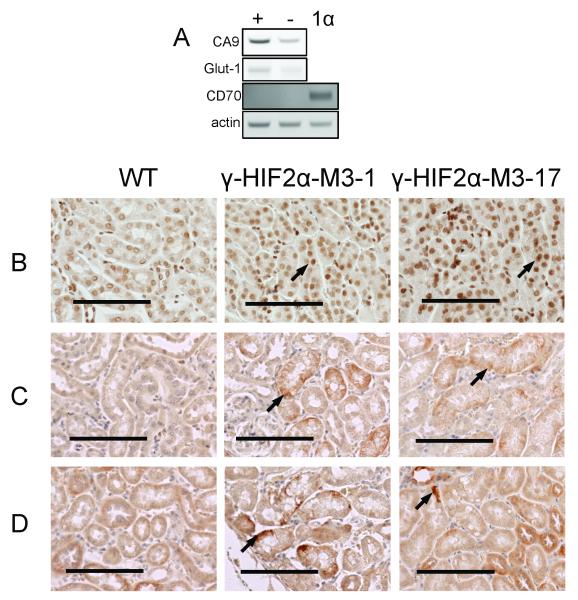

As described above, the HIF2μ transgene mRNA is expressed in TG+ kidneys (Fig. 1C). We next examined the expression by semi-quantitative RT-PCR of CA-IX (NP_647466) and Glut-1 (NP_035530), which are HIF2μ target genes, and CD70 (TNFSF7), which is a marker of human ccRCC (24-27) but not a known HIF2μ target gene. We detected increased mRNA levels of CA-IX and Glut-1, but not CD70 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Overexpression of HIF2μ target genes in the γ-HIF2μM3 kidneys.

Increased levels of HIF2μ target genes, e.g. CA-IX, Glut-1, in about 18 month old γ-HIF2μM3 kidney. A. Increased mRNA levels of CA-IX and Glut-1 and no expression of CD70 by semi-quantative RT-PCR. B, C, and D, representative images of the immunohistochemistry staining using HIF2μ (B), CA-IX (C) and Glut-1 (D) antibodies. Increased staining of HIF2μ (B, arrow), CA-IX (C, arrow) and Glut-1 (D, arrow) is only observed in the abnormal PTs of the TG+ mice. All scale bars represent 100 μm.

By immunohistochemistry, we confirmed increased HIF2μ, CA-IX, and Glut1 protein staining in the abnormal proximal tubules (PTs) (Fig. 2B, C, D, TG+), but not in the morphologically normal PTs of the same γ-HIF2μM3 mice. As expected, weak or no detectable HIF2μ, CA-IX, or Glut1 signals are observed in the PTs of TG- and WT mice (Fig. 2B, C, D, TG-).

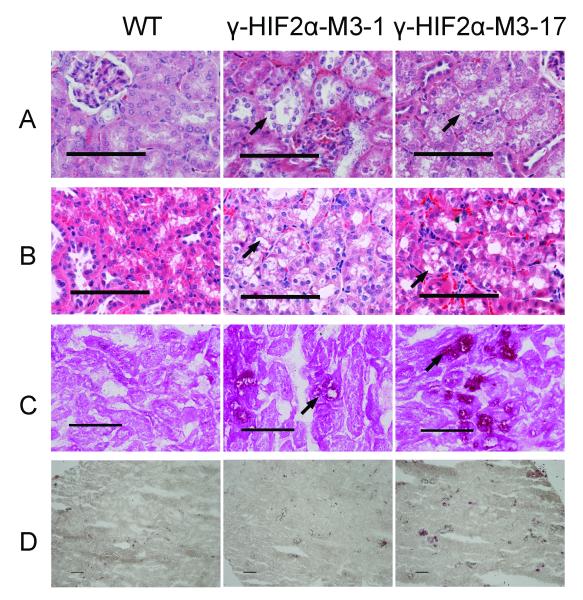

γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 TG+ mice exhibit mild vacuolation

Clear vacuoles were detected circumferentially around some, but not all, proximal tubule cell nuclei in the γ-HIF2μM3 mice. The γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 lines exhibited the strongest phenotype (Fig. 3A); the other lines had similar phenotypes, but displayed fewer PTs containing clear vacuoles (data not shown). We identified vacuoles with a pale, eosinophilic to clear feathery cytoplasm without displacement of the nucleus, consistent with glycogen accumulation and hydropic degeneration (Fig. 3A, arrows) in one year old γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 mice. Increased numbers of vacuoles in some proximal tubules were observed in two year old γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 mice (Fig. 3B, arrows). The histologically abnormal PT cells in TG+ mice were large, simple cuboidal epithelial cells (Fig. 3A and 3B) and these cells were surrounded by a tubular basement membrane, suggesting that these cells are under proper growth control. In ccRCC, the clear cytoplasm is caused by deposition of glycogen, phospholipids, and neutral lipids, particularly cholesterol esters (28). The cytoplasm of the abnormal cells in the HIF2μ TG+ mice contained increased amounts of glycogen, as demonstrated by Periodic Acid/Schiff (PAS) staining (Fig. 3C, arrows), but no increase in lipid in as determined by Oil Red O (ORO) staining (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. “Clear” cells in γ-HIF2μM3-43 mice.

Representative images of the histological morphology (A, B), PAS stain (C), and ORO stain (D) of the “clear” cells observed in γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 male TG+ and TG-kidneys. Vacuoles with a pale, eosinophilic to clear feathery cytoplasm without displacement of the nucleus are observed in 1 year old TG+ mice as compared to WT mice (A, arrow). Increased numbers of small vacuoles are observed in the cytoplasm of the PT cells from a 2 year old TG+ mouse as compared to WT mouse (B, arrow). Increased PAS stain (C, arrow) but no increased ORO staining (D) is observed in the cytoplasm of the TG+ kidney cells. All PTs stained by PAS were abnormal PTs with “clear” cells (C). All scale bars represent 100 μm.

We examined 21 mice of the γ-HIF2μM3-1 line and 16 γ-HIF2μM3-17 TG+ mice and compared them to WT mice. The oldest examined was a 33-month-old TG+ male mouse. Six TG+ mice older than 24 months, 13 between the ages of 18 and 24 months, 9 between the ages of 12 and 18 months, and 9 younger than 12 months were analyzed. No renal cysts or disorganized proximal tubules resembling in situ carcinoma were identified in any of the 37 TG+ animals examined.

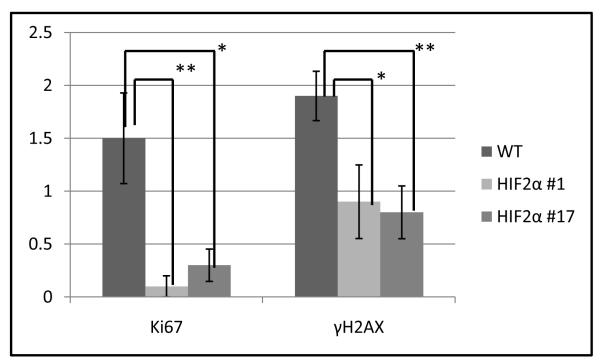

Expression of markers of proliferation and DNA double strand breaks in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice

Uncontrolled cell division/proliferation is one of the most prominent features of tumor cells. Genomic instability is another universal feature of tumor cells (29). An increased DNA mutation rate/genomic instability may cause neoplastic transformation (30). Ki67 is a marker for proliferation (31). The serine 139 phosphorylated form of H2A histone family, member X (γH2AX) is a widely used marker that indicates double strand breaks (DSBs). We examined Ki67 and γH2AX protein levels in TG+ vs. TG-kidneys (Fig. 4). We detected few Ki67+ and γH2AX+ cells in WT PTs (1.5 or 1.9 TG- cells/field, respectively). In the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice we observed statistically significantly decreased numbers of Ki67+ and γH2AX+ cells in the morphologically abnormal PTs. There were 0.1 (P=0.01, compared with TG-) and 0.3 (P=0.02, compared with TG-) Ki67+ cells/field in the γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 TG+ kidneys, respectively; there were 0.9 (P=0.03, compared with TG-) and 0.8 (P=0.005, compared with TG-) γH2AX+ cells/field in the γ-HIF2μM3-1 and γ-HIF2μM3-17 TG+ kidneys, respectively. Thus, the kidneys from TG+ mice exhibited a reduction in Ki67 and γH2AX staining relative to WT.

Figure 4. Decreased expression of γH2AX and Ki67 in the γ-HIF2μM3 kidneys.

The Ki67+ and γH2AX+ cells in 10 random fields of sections of 3 different TG+ and 3 WT kidneys were counted. All TG+ mice show a statistically significant decrease in Ki67+ and γH2AX+ cells. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01.

The transcriptome of γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys does not closely resemble the transcriptome of human ccRCC

We next examined gene expression using Next Generation Sequencing of the whole transcriptome (RNA-seq). We cut a thin slice of kidney cortex, which contains the preponderance of proximal tubules, and extracted total RNA for whole transcriptome analysis. High levels of proximal tubule marker mRNAs, e.g. GGT, indicate kidney cortex identity.

We identified upregulation of 1253 and downregulation of 749 transcripts in γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ vs WT kidney cortexes from 18 month old mice using less stringent conditions (fold change>1.2, t-test-BH-FDR-q-value<0.05, fisher-exact-test-BH-FDR-q-value <0.05). We identified upregulation of 206 and downregulation of 86 transcripts in γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ vs. WT mice when data were filtered with a more stringent condition (fold change>1.5, t-test-BH-FDR-q-value<0.01, fisher-exact-test-BH-FDR-q-value<0.01). Certain HIF2μ target genes, such as CA-IX, show significant overexpression in the HIF2μM3 TG+ vs. WT samples. However, other putative HIF2μ target genes, such as Oct4, cyclin D1, and TGFμ (32, 33), did not exhibit increased expression in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ vs. WT kidneys. Cyclin D1 shows a fold change of 1.1 (t-test-BH-FDR-q-value =0.49) and TGFμ transcripts show a fold change of 1.24, (t-test-BH-FDR-q-value =0.19).

To compare the transcriptome of the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys to human ccRCC, we identified the 20 genes most highly overexpressed at the RNA level in human ccRCC from Oncomine (Compendia Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI), combining five different datasets of human ccRCC patient samples (34-37). We identified a total of 5 datasets of Cancer vs. Normal Analysis of the ccRCC cancer type (Table 1). The five datasets we utilized are in Table 1. One of the 20 genes highly expressed in human ccRCC, EGLN3, shows significant upregulation in our γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys (>3 fold) (Table 1). However, the remaining 19 genes that are highly overexpressed in human ccRCC are either not changed (p<0.05) or are not significantly upregulated (<3 fold) in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ compared to WT kidneys (Table 1).

Table 1. Twenty genes showing the highest mRNA expression in human ccRCC compared to normal human kidney, from the Oncomine databas.

The list of the top 20 genes overexpressed at the RNA level in human ccRCC was retrieved from Oncomine by combining five different datasets of human ccRCC patient samples, totaling 175 patients. These five datasets are 1.) Hereditary ccRCC vs. Normal (32), 2.) Non-Hereditary ccRCC vs. Normal (32), 3.) ccRCC vs. Normal (33), 4.) ccRCC vs. Normal (34), and 5.) ccRCC vs. Normal (35). The fold changes in mRNA levels of these genes in γ-HIF2α-M3TG+ mice versus WT kidneys are listed. * One of these genes (EGLN3) shows statistically significant (P<0.05) overexpression (fold change>3) in HIF2αM3 TG+ vs. WT mice.

| Oncomine Median Rank |

Oncomine p-Value |

Oncomine Median Fold Change |

Gene | Gene Description | fold- change γ- HIF2α- M3/WT |

t-test-BH FDR-q- value |

fisher- exact-R γ- HIF2α- M3/WT BH-FDR- q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 5.55E-23 | 53.9 | NDUFA4L2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 4-like 2 |

1.7 | 0.049 | 1.95E-016 |

| 14 | 3.91E-13 | 16.5 | C7orf68 | chromosome 7 open reading frame 68, or hypoxia inducible gene 2 |

1.4 | 0.071 | 0.005 |

| 14 | 2.82E-11 | 12.5 | ENO2 | enolase 2, gamma neuronal | 1.0 | 0.816 | 1 |

| 16 | 9.50E-19 | 12.2 | EGLN3 | EGL nine homolog 3 (C. elegans) |

3.6 | 0.007 | 0 |

| 21 | 1.73E-14 | 11.0 | GFBP3 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 |

1.7 | 0.054 | 0 |

| 25 | 1.23E-10 | 12.2 | SPAG4 | sperm associated antigen 4 | 1.3 | 0.571 | 0.789 |

| 28 | 2.83E-17 | 15.0 | AHNAK2 | AHNAK nucleoprotein 2 | 1.5 | 0.518 | 0.071 |

| 30 | 3.79E-7 | 8.4 | TMCC1 | transmembrane and coiled coil domains 1 |

1.1 | 0.199 | 0.002 |

| 36 | 2.19E-16 | 8.6 | RNASET2 | ribonuclease T2A; RNASET2A | 1.1 | 0.934 | 0.531 |

| 38 | 1.93E-13 | 8.2 | CAV1 | caveolin 1, caveolae protein1 | 0.8 | 0.038 | 1.33E-036 |

| 41 | 2.54E-13 | 7.1 | SLC16A3 | solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters),member 3 |

0.8 | 0.114 | 0.002 |

| 46 | 6.8E-10 | 4.6 | LCP2 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 2 | 1.2 | 0.600 | 0.161 |

| 47 | 6.92E-16 | 18.0 | CA-IX | carbonic anhydrase 9 | 1.9 | 0.032 | 7.13E-093 |

| 48 | 7.84E-10 | 15.4 | NETO2 | neuropilin (NRP) and tolloid(TLL)-like 2 | 1.3 | 0.539 | 0.299 |

| 49 | 8.25E-10 | 2.6 | IFNGR2 | interferon gamma receptor 2 | 1.2 | 0.113 | 4.71E-016 |

| 57 | 3.12E-15 | 4.9 | ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette, sub- family G (WHITE), member 1 |

1.4 | 0.185 | 7.39E-012 |

| 57 | 1.37E-12 | 2.3 | UBE2L6 | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2L 6 |

1.0 | 0.902 | 0.978 |

| 59 | 1.59E-10 | 3.2 | DIAPH2 | diaphanous homolog 2 (Drosophila) |

1.1 | 0.329 | 0.003 |

| 59 | 1.50E-9 | 2.4 | ALDOA | aldolase A, fructose bisphosphate |

1.0 | 0.759 | 4.91E-005 |

| 59 | 1.69E-8 | 3.4 | SLC15A4 | solute carrier family 15, member 4 |

1.0 | 0.651 | 0.108 |

We also identified the top genes overexpressed at the RNA level in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ compared to WT kidneys, and compared the transcript levels of these genes to those in the combined Oncomine datasets used in Table 1. One of these genes, CD163 molecule-like 1, shows overexpression (fold change>3) in the combined Oncomine datasets (Table 2). The other 19 genes that are highly overexpressed in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ relative to WT kidneys do not show overexpression in the combined Oncomine human ccRCC vs. normal datasets (Table 2). We conclude from analysis of these data that expression of a mutant, constitutively active HIF2μ protein in kidney PTs does not result in a transcriptome that closely resembles that of human ccRCC.

Table 2. Top 20 genes overexpressed at the mRNA level in the γ-HIF2α-M3 TG+ vs. WT kidneys by RNAseq.

The list of the top 20 genes overexpressed at the RNA level in the γ-HIF2α-M3 TG+ vs. WT kidneys was compiled from the RNAseq results. The median fold change in mRNA levels of these genes in human ccRCC was compiled from Oncomine by combining five different sets of human ccRCC patient samples, totaling 175 patients (see Table 1). Genes that has no measurements from all five datasets were excluded from this list. One of these genes (Cd163l1*) shows overexpression (fold change>3) in the Oncomine datasets.

| fold- changeγ- HIF2α- M3/WT |

t-test-BH- FDR-q- value |

fisher-exact- R γ-HIF2α- M3/WT-BH- FDR-q-value |

Element ID | Gene Description | Human ccRCC/normal kidney Median Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 121.37 | 0 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000025515 | mucin 2 | −1.09 |

| 57.1 | 4.21E-006 | 4.46E-147 | ENSMUSG00000034486 | gastrulation brain homeobox 2 | −1.02 |

| 48.32 | 0 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000030111 | alpha-2-macroglobulin | 1.81 |

| 45.86 | 0 | 7.48E-083 | ENSMUSG00000026468 | LIM homeobox protein 4 | 1.77 |

| 36.31 | 2.03E-005 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000050645 | defensin beta 19 | 0.38 |

| 33.13 | 0 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000032080 | apolipoprotein A-IV | −1.23 |

| 21.74 | 0.01 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000056296 | synaptoporin | −1.15 |

| 19.73 | 0.01 | 1.71E-144 | ENSMUSG00000024008 | copine V; similar to Copine V | 1.54 |

| 19.15 | 0.01 | 2.02E-042 | ENSMUSG00000018893 | myoglobin | −1.09 |

| 17.16 | 1.27E-005 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000032081 | apolipoprotein C-III | −1.7 |

| 17.14 | 0 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000021708 | RAS protein-specific guanine nucleotide-releasing factor 2 |

1.57 |

| 15.5 | 0.02 | 5.83E-090 | ENSMUSG00000000731 | autoimmune regulator (autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy) |

−1.08 |

| 14.24 | 0.03 | 1.05E-033 | ENSMUSG00000042268 | solute carrier family 26, member 9 |

−0.23 |

| 10.97 | 6.47E-005 | 9.41E-094 | ENSMUSG00000025461 | CD163 molecule-like 1 * | 3.15 |

| 7.49 | 0.01 | 0 | ENSMUSG00000038418 | early growth response 1 | −1.16 |

| 6.49 | 0.01 | 1.72E-038 | ENSMUSG00000030236 | solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1b2 |

−1.07 |

| 6.26 | 0.01 | 6.27E-010 | ENSMUSG00000052468 | peripheral myelin protein2 | −1.14 |

| 6.14 | 0.01 | 2.65E-009 | ENSMUSG00000054667 | insulin receptor substrate 4; similar to insulin receptor substrate 4 |

−1.16 |

| 5.62 | 0.02 | 3.81E-011 | ENSMUSG00000026959 |

glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDA1 (zeta 1) |

1.34 |

| 5.39 | 0.05 | 1.46E-271 | ENSMUSG00000024411 | aquaporin 4 | −1.01 |

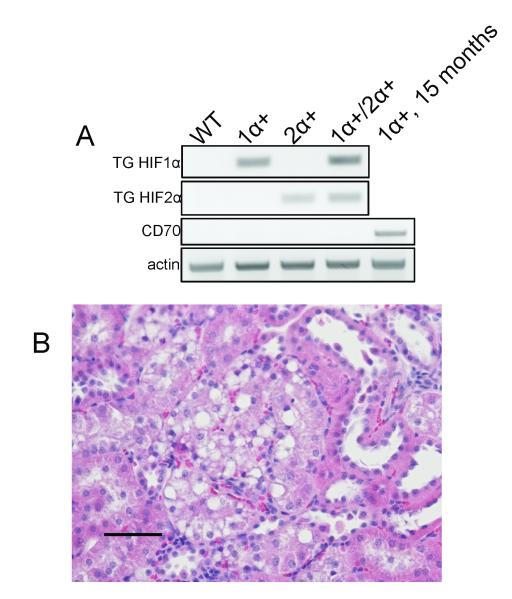

Kidneys from γ-HIF1μM3(TRACK);γ-HIF2μM3 double TG+ mice are similar to kidneys from γ-HIF1μM3 TG+ mice

We also examined kidneys from 8 γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 double TG+ male mice (from 6 to 11 months old). Both HIF1μM3 and HIF2μM3 transgenes are expressed in the kidneys from the γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 double TG+, as detected by RT-PCR using transgene specific primers (Fig. 5A). We did not detect CD70 transcripts in these double TG+ kidneys (Fig. 5A), but we did detect CD70 transcripts in the kidneys of 15 month old TRACK kidneys, as reported (13). Seven of eight γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice did not show any greater tumorigenesis in the kidney cortex than the γ-HIF1μM3 single TG+ TRACK mice. One of the double TG+ mice had kidneys with a few disorganized proximal tubules (Fig. 5B), resembling those observed in TRACK mice aged 14 months or older (13). Since seven of the eight γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 double TG+ mice showed no pathological features indicative of greater tumorigenicity than that in the TRACK mice, which express only a mutated, constitutively active from of HIF1μ, we conclude that a mutated, constitutively active form of HIF2μ does not promote tumorigenesis in the presence of a constitutively active HIF1μ in the kidney proximal tubules.

Figure 5. Transgene expression and histopathology in γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 double TG+ mice.

A. HIF1μM3 and HIF2μM3 transcripts are expressed in kidneys from double TG+, 11 month mice. CD70 transcripts are not detected in the double TG+ kidneys, but are detected in kidneys from 15 month old HIF1μM3-43 kidneys. B. One disorganized proximal tubule in a γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 double TG+, 11 month old mouse. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

Discussion

The γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys do not resemble human ccRCC histologically

Several researchers have suggested that overexpression of HIF2μ is a key step in the development of ccRCC (4). However, we detected no obvious ccRCC phenotype in the kidneys of γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice. In contrast, in our γ-HIF1μ-M3(TRACK) transgenic mice we identified two types of vacuolation: large round, discrete vacuoles, displacing the nucleus, that contained lipid accumulation (13); and vacuoles with a pale, eosinophilic to clear feathery cytoplasm without displacement of the nucleus, consistent with glycogen accumulation and hydropic degeneration (13). Although some PTCs of these γ-HIF2μM3 transgenic mice contain clear spaces around the nuclei, the vacuoles do not resemble the large, almost completely clear vacuoles found in the TRACK kidneys (13) and in human ccRCC (38). Furthermore, no renal cysts or disorganized PTs resembling in situ carcinoma were identified in any of the 37 TG+ animals examined, including 6 between 24 to 33 months old. These data suggest that overexpression of HIF2μ alone in PT cells does not resemble ccRCC histologically.

The γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys do not show neoplastic transformation and do not express cancer markers

That there is no ccRCC phenotype in these γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys is unexpected given previous data in the literature using cultured human ccRCC cells (9-12, 32, 33, 39). HIF2μ has previously been reported to be more oncogenic than HIF1μ and to play an important role in ccRCC carcinogenesis (4, 40, 41). However, we detected no renal cysts or neoplasia in the kidneys of γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice. In contrast, we observed multiple renal cysts and disorganized PTs resembling in situ carcinoma in the γ-HIF1μ-M3 TG+ TRACK mice (13). Uncontrolled cell division/proliferation and genomic instability are two of the most prominent features of tumor cells. By staining using Ki67 or γH2AX antibodies, we previously showed elevated expression of both Ki67 and γH2AX in γ-HIF1μ-M3 TG+ mice (13). However, we did not detect higher levels of Ki67 or γH2AX in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys (Fig. 4). In fact, the levels were lower than in WT, suggesting that constitutively active HIF2μ reduces cell proliferation and genomic instability. The CD70 protein level is higher in the majority of human ccRCC and CD70 is a marker and therapeutic target in human ccRCC (24). CD70 mRNA levels are several fold higher in older TRACK vs WT mice (13). However, we didn’t observe any CD70 mRNA expression in 18 month old γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys by RT-PCR (Fig. 2), again indicating a lack of neoplastic transformation.

Using the methods described in the supplemental data, we calculated and compared the relative levels of the HIF1μM3 and HIF2μM3 transcripts in the HIF1μM3 TG+ (TRACK) mice and HIF2μM3 TG+ mice, respectively. The HIF2μM3 mRNA levels in the HIF2μM3 TG+ mice are about 26% of the HIF1μM3 mRNA levels in the highest expressing TRACK line, and about the same as the HIF1μM3 mRNA levels in other TRACK transgenic lines (supplemental Table S2). The HIF2μM3 protein is also overexpressed in the HIF2μM3 kidneys (Fig. 2B). Thus, the difference we observe in tumorigenic phenotype is likely a result of the specific HIF protein expressed and not the level of transgene expression.

The transcriptome of γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys does not closely resemble the transcriptome of human ccRCC

Furthermore, we compared the changes in gene expression in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys to human ccRCC. Only one of the top 20 genes overexpressed in five different sets of human ccRCC patient samples showed statistically significant overexpression in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys (Table 1). In fact, some of these genes showed a statistically significant reduction in expression, e.g. caveolin 1 showed a fold change of 0.79 (t-test-BH-FDR-q-value =0.04) when we compared the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ to WT kidneys. Conversely, only one of the top 20 genes overexpressed at the RNA level in the γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ kidneys showed overexpression in the combined human ccRCC Oncomine datasets (Table 2). These data further indicate that expression of mutated, constitutively active HIF2μ in kidney PTCs does not lead to a phenotype resembling human ccRCC, though some HIF2μ target genes, such as CA-IX, show increased expression in the PTCs of kidneys of γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice (Fig. 2). We did not detect high levels of the putative HIF2μ targets TGFμ, cyclin D1, and Oct4 (42, 43) in the HIF2μM3 TG+mice. This might be because different types of cells were used in those assays. For example, Oct4 was identified as a HIF2μ target in embryonic stem cells (42), while TGFμ and cyclin D1 were identified as HIF2μ targets in cultured ccRCC cancer cells (43).

Expression of constitutively active HIF2μ does not cause neoplastic transformation of proximal tubule cells

Our data suggest that expression of a mutated, constitutively active HIF2μ in proximal tubule cells, the cells from which ccRCC originates (44, 45), does not cause neoplastic transformation. This conclusion is also supported by a recent publication reporting that overexpression of a similarly mutated (P405A, P530G, N851A), constitutively active HIF2μ in murine distal tubule cells is insufficient for renal carcinogenesis (16). However, it is possible that HIF2μ may cooperate with HIF1μ to drive renal cell carcinogenesis, since an increase in HIF2μ expression is seen after an increase in HIF1μ expression in early kidney lesions in VHL disease patients (46). We crossed our TRACK and γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice to determine if constitutive activation of both HIF1μ and HIF2μ results in more rapid neoplastic transformation of normal PTCs. From pathological examination of eight γ-HIF1μM3;γ-HIF2μM3 TG+ mice up to 11 months old, we conclude that constitutively active HIF2μ does not result in more rapid neoplastic transformation in the presence of constitutively active HIF1μ in the kidney. However, we can’t rule out the possibility that this lack of tumorigenicity of HIF2μM3 is caused by potential biological differences between human and mouse kidney PT cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank WCMC, the Turobiner Kidney Cancer Research Fund, and the Genitourinary Oncology Research Fund for funding. Dr. Fu holds the Robert H. McCooey Genitourinary Oncology Research Fellowship. Dr. Wang was partially supported by the Nutrition and Cancer Prevention R25 Training Grant (NCIR25105012). We thank Dr. Simon for the WT HIF2μ construct, Dr. Campagne for the help with GobyWeb software, and Dr. Tuo Zhang (Genomics Resources Core Facility of WCMC) for help with quantification of GGT-HIF2μM3 data.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Maher ER, Kaelin WG., Jr. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 1997;76:381–91. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199711000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patard JJ, Leray E, Rioux-Leclercq N, Cindolo L, Ficarra V, Zisman A, et al. Prognostic value of histologic subtypes in renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2763–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linehan WM, Pinto PA, Srinivasan R, Merino M, Choyke P, Choyke L, et al. Identification of the genes for kidney cancer: opportunity for disease-specific targeted therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:671s–9s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaelin WG., Jr. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and clear cell renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:680s–4s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordan JD, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors: central regulators of the tumor phenotype. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2007;17:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes & development. 1997;11:72–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaelin WG. Von hippel-lindau disease. Annual review of pathology. 2007;2:145–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.092049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr. Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS biology. 2003;(1):E83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmer M, Doucette D, Siddiqui N, Iliopoulos O. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor is sufficient for growth suppression of VHL−/−tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo K, Klco J, Nakamura E, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr. Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer cell. 2002;1:237–46. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:5675–86. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu L, Wang G, Shevchuk MM, Nanus DM, Gudas LJ. Generation of a Mouse Model of Von Hippel-Lindau Kidney Disease Leading to Renal Cancers by Expression of a Constitutively Active Mutant of HIF1alpha. Cancer research. 2011;71:6848–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiesener MS, Munchenhagen PM, Berger I, Morgan NV, Roigas J, Schwiertz A, et al. Constitutive activation of hypoxia-inducible genes related to overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in clear cell renal carcinomas. Cancer research. 2001;61:5215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorevic G, Matusan-Ilijas K, Babarovic E, Hadzisejdic I, Grahovac M, Grahovac B, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha correlates with vascular endothelial growth factor A and C indicating worse prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:40. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schietke RE, Hackenbeck T, Tran M, Gunther R, Klanke B, Warnecke CL, et al. Renal tubular HIF-2alpha expression requires VHL inactivation and causes fibrosis and cysts. PLoSONE. 2012;7:e31034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medina Villaamil V, Aparicio Gallego G, Santamarina Cainzos I, Valladares Ayerbes M, Anton Aparicio LM. Searching for Hif1-alpha interacting proteins in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14:698–708. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0857-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswas S, Charlesworth PJ, Turner GD, Leek R, Thamboo PT, Campo L, et al. CD31 angiogenesis and combined expression of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha are prognostic in primary clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (CC-RCC), but HIFalpha transcriptional products are not: implications for antiangiogenic trials and HIFalpha biomarker studies in primary CC-RCC. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1717–25. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sivanand S, Pena-Llopis S, Zhao H, Kucejova B, Spence P, Pavia-Jimenez A, et al. A validated tumorgraft model reveals activity of dovitinib against renal cell carcinoma. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:137ra75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacquemin E, Bulle F, Bernaudin JF, Wellman M, Hugon RN, Guellaen G, et al. Pattern of expression of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in rat liver and kidney during development: study by immunochemistry and in situ hybridization. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1990;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199007000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terzi F, Burtin M, Hekmati M, Federici P, Grimber G, Briand P, et al. Targeted expression of a dominant-negative EGF-R in the kidney reduces tubulo-interstitial lesions after renal injury. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;106:225–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorff KC, Chambwe N, Zeno Z, Shaknovich R, Campagne F. GobyWeb: simplified management and analysis of gene expression and DNA methylation sequencing data. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069666. arXiv http://arxivorg/abs/12116666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Adam PJ, Terrett JA, Steers G, Stockwin L, Loader JA, Fletcher GC, et al. CD70 (TNFSF7) is expressed at high prevalence in renal cell carcinomas and is rapidly internalised on antibody binding. British journal of cancer. 2006;95:298–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jilaveanu LB, Sznol J, Aziz SA, Duchen D, Kluger HM, Camp RL. CD70 expression patterns in renal cell carcinoma. Human pathology. 2012;43:1394–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McEarchern JA, Smith LM, McDonagh CF, Klussman K, Gordon KA, Morris-Tilden CA, et al. Preclinical characterization of SGN-70, a humanized antibody directed against CD70. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7763–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang QJ, Hanada KI, Robbins PF, Li YF, Yang JC. Distinctive Features of the Differentiated Phenotype and Infiltration of Tumor-reactive Lymphocytes in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer research. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebhard RL, Clayman RV, Prigge WF, Figenshau R, Staley NA, Reesey C, et al. Abnormal cholesterol metabolism in renal clear cell carcinoma. Journal of lipid research. 1987;28:1177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charames GS, Bapat B. Genomic instability and cancer. Current molecular medicine. 2003;3:589–96. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loeb KR, Loeb LA. Genetic instability and the mutator phenotype. Studies in ulcerative colitis. The American journal of pathology. 1999;154:1621–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65415-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. Journal of cellular physiology. 2000;182:311–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alt JR, Cleveland JL, Hannink M, Diehl JA. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 nuclear export and cyclin D1-dependent cellular transformation. Genes & development. 2000;14:3102–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Twardzik DR, Todaro GJ, Marquardt H, Reynolds FH, Jr., Stephenson JR. Transformation induced by Abelson murine leukemia virus involves production of a polypeptide growth factor. Science (New York, NY. 1982;216:894–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6177040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beroukhim R, Brunet JP, Di Napoli A, Mertz KD, Seeley A, Pires MM, et al. Patterns of gene expression and copy-number alterations in von-hippel lindau disease-associated and sporadic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Cancer research. 2009;69:4674–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gumz ML, Zou H, Kreinest PA, Childs AC, Belmonte LS, LeGrand SN, et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 loss contributes to tumor phenotype of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4740–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenburg ME, Liou LS, Gerry NP, Frampton GM, Cohen HT, Christman MF. Previously unidentified changes in renal cell carcinoma gene expression identified by parametric analysis of microarray data. BMC Cancer. 2003;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yusenko MV, Kuiper RP, Boethe T, Ljungberg B, van Kessel AG, Kovacs G. High-resolution DNA copy number and gene expression analyses distinguish chromophobe renal cell carcinomas and renal oncocytomas. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz JI, Mora LB, Hakam A. The Mainz Classification of Renal Cell Tumors. Cancer Control. 1999;6:571–9. doi: 10.1177/107327489900600603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gidekel S, Pizov G, Bergman Y, Pikarsky E. Oct-3/4 is a dose-dependent oncogenic fate determinant. Cancer cell. 2003;4:361–70. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordan JD, Lal P, Dondeti VR, Letrero R, Parekh KN, Oquendo CE, et al. HIF-alpha effects on c-Myc distinguish two subtypes of sporadic VHL-deficient clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer cell. 2008;14:435–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel SA, Simon MC. Biology of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in development and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:628–34. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Covello KL, Kehler J, Yu H, Gordan JD, Arsham AM, Hu CJ, et al. HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes & development. 2006;20:557–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim WY, Kaelin WG., Jr. Molecular pathways in renal cell carcinoma--rationale for targeted treatment. Seminars in oncology. 2006;33:588–95. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace AC, Nairn RC. Renal tubular antigens in kidney tumors. Cancer. 1972;29:977–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197204)29:4<977::aid-cncr2820290444>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida SO, Imam A, Olson CA, Taylor CR. Proximal renal tubular surface membrane antigens identified in primary and metastatic renal cell carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandriota SJ, Turner KJ, Davies DR, Murray PG, Morgan NV, Sowter HM, et al. HIF activation identifies early lesions in VHL kidneys: evidence for site-specific tumor suppressor function in the nephron. Cancer cell. 2002;1:459–68. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.