Background: Chloroplast ATP synthase activity is regulated by both light and metabolic factors, but the relationship between these regulatory modes is not established.

Results: Mutating three highly conserved acidic amino acid residues in the γ subunit alters light- but not metabolism-induced regulation.

Conclusion: Metabolism and light regulation operates via distinct mechanisms.

Significance: The chloroplast ATP synthase is a key control point for the light and dark reactions of photosynthesis.

Keywords: ATP Synthase, Chloroplast, Photosynthesis, Proton Transport, Redox Regulation, Thioredoxin

Abstract

The chloroplast CF0-CF1-ATP synthase (ATP synthase) is activated in the light and inactivated in the dark by thioredoxin-mediated redox modulation of a disulfide bridge on its γ subunit. The activity of the ATP synthase is also fine-tuned during steady-state photosynthesis in response to metabolic changes, e.g. altering CO2 levels to adjust the thylakoid proton gradient and thus the regulation of light harvesting and electron transfer. The mechanism of this fine-tuning is unknown. We test here the possibility that it also involves redox modulation. We found that modifying the Arabidopsis thaliana γ subunit by mutating three highly conserved acidic amino acids, D211V, E212L, and E226L, resulted in a mutant, termed mothra, in which ATP synthase which lacked light-dark regulation had relatively small effects on maximal activity in vivo. In situ equilibrium redox titrations and thiol redox-sensitive labeling studies showed that the γ subunit disulfide/sulfhydryl couple in the modified ATP synthase has a more reducing redox potential and thus remains predominantly oxidized under physiological conditions, implying that the highly conserved acidic residues in the γ subunit influence thiol redox potential. In contrast to its altered light-dark regulation, mothra retained wild-type fine-tuning of ATP synthase activity in response to changes in ambient CO2 concentrations, indicating that the light-dark- and metabolic-related regulation occur through different mechanisms, possibly via small molecule allosteric effectors or covalent modification.

Introduction

The chloroplast CF0-CF1-ATP synthase (ATP synthase)2 drives the reversible synthesis of ATP from ADP and Pi using energy from the light-driven proton electrochemical gradient, or proton motive force (pmf) (1, 2). This multisubunit complex is composed of two subcomplexes. The membrane-embedded CF0 subcomplex converts energy from proton flux into rotational motion. The water-soluble CF1 subcomplex couples this rotational motion to the synthesis of ATP. The architecture of the chloroplast complex is similar to that of bacterial and mitochondrial orthologues (3, 4). The F1 subcomplex, composed of five subunits designated (in common nomenclature) α, β, γ, δ, and ϵ, with stoichiometry of 3:3:1:1:1, contains three catalytic nucleotide binding sites in the β subunits and three noncatalytic nucleotide-binding sites at the water-soluble thylakoid membrane surface (5, 6). The α and β subunits form a hexagonal α3β3 ring around the γ subunit as a central stalk, whereas δ and ϵ subunits have a function in stabilizing the structure and inhibiting ATP hydrolysis activity, respectively (7). The integral membrane CF0 subcomplex contains four subunits (I, II, III14, and IV, also called b, b′, c, and a) and couples transmembrane proton movement with rotational torque generation (8, 9).

The chloroplast ATP synthase is regulated at multiple levels. As with other ATP synthases, it is activated by imposition of pmf. An additional level of regulation occurs by redox modulation of a disulfide/sulfhydryl pair on the γ subunit via thioredoxin (1, 9–13). This redox regulation modulates the amplitude of pmf required to activate the ATP synthase and has been proposed to prevent “wasteful” ATP hydrolysis in the dark by reversal of the ATP synthase reaction (14). Thiol modulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase is structurally assigned to a chloroplast-specific 9-amino acid “loop” inserted in the γ subunit containing a pair of redox-active cysteine residues (Cys199 and Cys205 in Arabidopsis thaliana) (Fig. 1A).

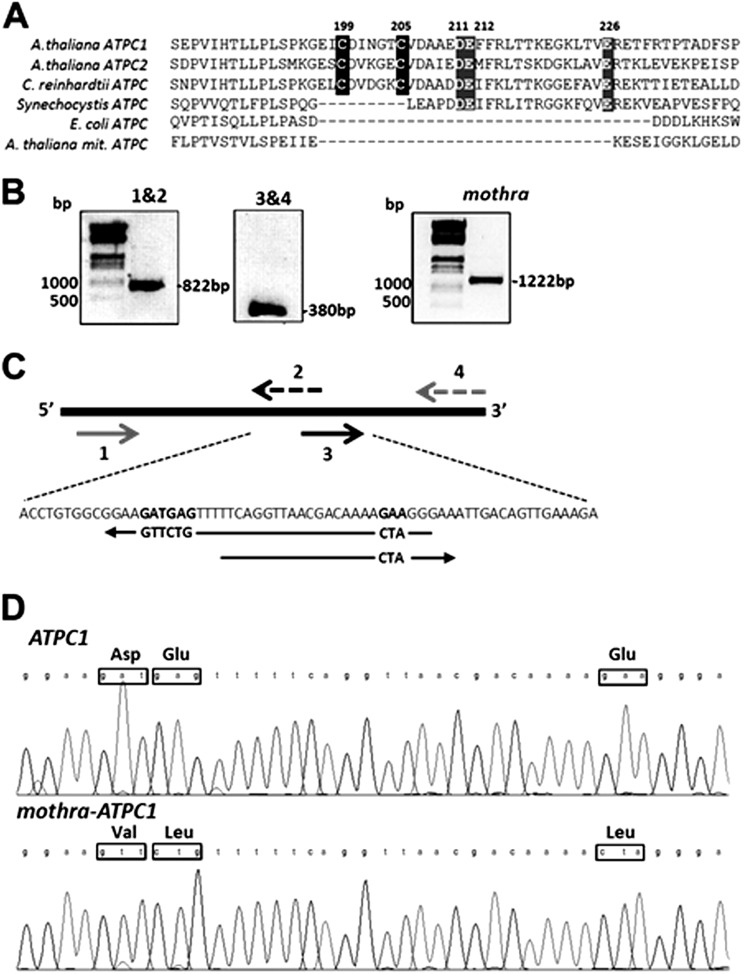

FIGURE 1.

A, alignment of partial protein sequences of γ subunits from different sources, chloroplast ATPC1 and ATPC2 from A. thaliana, ATPC of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Synechocystis, Escherichia coli, and mitochondrial ATPC subunit of A. thaliana. The cysteine residues (black background) involved the redox modulation of plant and algal plastid ATP synthase, and the highly conserved acidic residues are indicated by a gray background. B, oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of the ATPC1 gene. SmaI restriction-sited forward primer and modified ATPC1 reverse primer (1 and 2) amplified a fragment of 822 bp; modified ATPC1 forward primer and XbaI restriction-sited reverse primer (3 and 4) amplified a fragment of 380 bp. C, details of the mutagenesis strategy. D, sequence analysis of wild-type and mutant γ subunit.

Thiol activation occurs at very low irradiances and thus has been proposed to act as an “on-off” switch (15), probably because of the relatively high redox midpoint potential of the regulatory thiol/disulfide couple. The determinants of this redox potential are not understood, but the effects of mutagenesis suggest the involvement of charged amino acids in a region (Glu210-Glu212) (16–19).

It has also been shown that ATP synthase activity is modulated during steady-state photosynthesis in vivo upon altering metabolic or physiological conditions, e.g. by decreasing atmospheric CO2 or O2 levels (20), imposing environmental stress conditions (e.g. drought) (21), or altering the capacity of the Calvin-Benson cycle and starch synthesis (22–24). It has thus been proposed that ATP synthase modulation represents an important feedback regulatory mechanism, sensing the metabolic status of the stroma and, in response, adjusting the efflux of protons from the lumen to modulate the lumen pH-dependent down-regulation of light capture and electron transfer. Several mechanisms for this “metabolism-related” regulation of the ATP synthase have been proposed: thiol modulation, depletion of substrate Pi, or binding of small allosteric effectors or phosphorylation; but these have not yet been directly tested. In this work, we describe a site-directed γ subunit mutant of Arabidopsis, which alters the redox modulation of the ATP synthase without decreasing its maximal activity, allowing us to test one of these models.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Modified Thioredoxin-regulated ATP Synthase (Mothra)

The full-length coding sequence of the intronless ATPC1 nuclear gene was amplified by Pyrococcus furiosus polymerase from wild-type genomic DNA using the SmaI restriction site forward primer in the 5′ end of the gene 5′-AACAAAAAAATGGCTTGCTCTAATCTAACA-3′ and the XbaI restriction-sited reverse primer in the 5′ end of the gene 5′-AAGAGGGTTCTAGACAAATCAAACCTGTGC-3′.

The PCR fragment was inserted in the cloning vector PCR-Script Amp SK(+) (Stratagene). Three conserved acidic residues in the regulatory loop region (Fig. 1, B and C), namely Asp211, Glu212, and Glu226, were modified by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis using the cloned ATPC1 gene as template DNA. The ATPC1 gene was amplified in two-step amplification with SmaI restriction sites forward primer and modified ATPC1 reverse primer 5′-CCCTAGTTTTGTCGTTAACCTGAAAAACAGAACTTCCGC-3′ and then, as second step, modified ATPC1 forward primer 5′-GTTTTTCAGGTTAACGACAAAACTAGGGAAATT-3′ and XbaI restriction-sited reverse primer on the PCR-Script Amp SK(+). The mutated DNA was excised with SmaI and XbaI and inserted into binary vector pSEX001-VS under control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (25). Successful cloning was confirmed by sequencing (Fig. 1D). The modified ATPC1 on the binary vector was transformed into Agrobacterium GV3101 strain and infected into plants heterozygous for the lethal dpa1 mutation (26).

Transformants carrying mothra were segregated on solid Murashige-Skoog medium with 10 mg/liter sulfadiazine. A dpa1 line complemented with ATPC1 also was constructed using the same strategy, yielding dpa1 lines carrying 35S::ATPC1, which we term the “complemented lines.”

Wild-type A. thaliana (ecotype Wassileskija), complemented lines, and mothra (containing neutral residues Val211, Leu212, and Leu226 in place of highly conserved acidic amino acids Asp211, Glu212, and Glu226) were grown on soil under continuous light period at 30–50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at 22 °C for 4 weeks as described (17).

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analyses

Plant leaves were frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen, and proteins were extracted in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mm EGTA, 10 mm EDTA, and 10 mm DTT. The extracts were fractionated by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The separated insoluble fractions, including thylakoid membrane proteins, were washed twice with extraction buffer and once with 80% acetone to remove pigments. The insoluble proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE after dissolving in 100 mm Na2CO3, 10% (w/v) sucrose, 50 mm DTT, and 1.5% (w/v) SDS. The relative contents of γ subunit in wild type and mothra were estimated by Western blotting, as described previously (17). The γ subunit protein was detected by specific antibodies raised against chloroplast γ1 subunit.

In Vivo Spectroscopic Assays

Chlorophyll a fluorescence and flash-induced electrochromic shift (ECS) parameters were measured, as described previously (27, 28). Linear electron flow (LEF) and energy-dependent exciton quenching (qE) were estimated from saturation-pulse fluorescence yield under steady-state actinic lights and light-induced pmf (ECSt). The conductivity of thylakoid membrane to protons (gH+), attributable to activity of the ATP synthase, was estimated from the first-order exponential decay of the dark interval relaxation kinetic changes in absorbance associated with the ECS at 520 nm, with reference wavelengths taken at 505 and 535 nm (21, 23, 27, 28). The relative extent of steady-state proton flux across the thylakoid membrane (υH+) was estimated from the initial slope of the ECS decay (27, 29). To account for variations in leaf thickness and pigmentation, ECS measurements were normalized to the extent of the rapid rise in ECS induced by a saturating, single-turnover flash (15). The correction was small, with rapid ECS phases mothra and complemented lines that were 1.00 ± 0.004 and 1.17 ± 0.01 times than wild type. Steady-state fluorescence and ECS assays also were repeated under a range of atmospheric CO2 concentrations using a gas exchange system (LI-COR) to control CO2 levels.

Non saturating flash-induced relaxation kinetics analysis of the ECS signal was performed to determine the activation state of the ATP synthase in the dark. Flash-induced relaxation kinetics experiments were performed 1 and 60 min after preillumination for 2 min with 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 as described previously (17, 21).

Equilibrium Redox Titrations and Redox State of ATP Synthase γ-Subunit

In situ redox titrations of ATP synthase were performed using the approach of Wu and co-workers (1, 18), detecting the ATP synthase activity by analyzing the kinetics of flash-induced ECS signals as described in Ref. 17. Relative ATP synthase activity was estimated from the reciprocal ECS decay lifetime, assuming pseudo-first-order behavior (27).

The redox state of the γ subunit of chloroplast ATP synthase was probed using the binding of 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (AMS) followed by nonreducing SDS-PAGE (17, 30). Oxidizing and reducing conditions were achieved by infiltration into 1-cm leaf discs of 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and 20 mm Tricine containing 100 μm methyl viologen for oxidizing conditions or 20 mm reduced dithiothrietol (DTT) for reducing conditions. Following these treatments, discs were incubated for 30 min in darkness at room temperature, followed by freezing and grinding in liquid nitrogen. Insoluble proteins were isolated by centrifugation and washing with 80% acetone. The protein precipitates were dissolved in freshly prepared solution containing 1% SDS, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 15 mm AMS and then immigrated by SDS-PAGE using running buffer lacking reducing agent as described in Ref. 16. Redox states of the γ subunits in wild type and the mothra were visually detected using an antibody against the γ1 subunit using Western blotting.

RESULTS

Effects of Altering Three Highly Conserved Acidic Residues in the Regulatory γ Subunit

As a part of a wider effort to determine the functions of key γ subunit residues in ATP synthase catalysis and regulation, three conserved acidic residues in the vicinity of the γ subunit regulatory cysteine residues, Asp211, Glu212, and Glu226 (Fig. 1A), were mutated by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis to generate a mutant, mothra, in which these were modified to neutral residues Val211, Leu212, and Leu226, respectively, as described in Fig. 1, B–D. These residues are in the loop containing the regulatory cysteine residues, a region that is apparently quite flexible and can accommodate large changes (point mutations and deletions) albeit with altered regulatory and catalytic behaviors (18, 19, 31).

Effects of Mothra on Photosynthesis under Ambient CO2 and O2

Wild-type, mothra, and complemented lines had similar maximal photosystem II quantum yields (0.80 ± 0.0028, 0.79 ± 0.005, and 0.79 ± 0.002, respectively, n = 3), as measured by saturation pulse fluorescence yield changes (FV/FM), likely indicating no effects on the stability of photosystem II. LEF was nearly identical in wild type, complemented lines, and mothra at low to 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 irradiance and ambient CO2 and 21% O2 (Fig. 2A). LEF saturated more readily at irradiances higher than 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1, LEF in mothra, and complemented lines, indicating the imposition of a rate limitation at high fluxes. The extents of photoprotective qE response in mothra were 20–50% higher in mothra than wild-type or the complemented line at irradiance above approximately 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, possibly indicating increased light-induced acidification of the lumen (Fig. 2B).

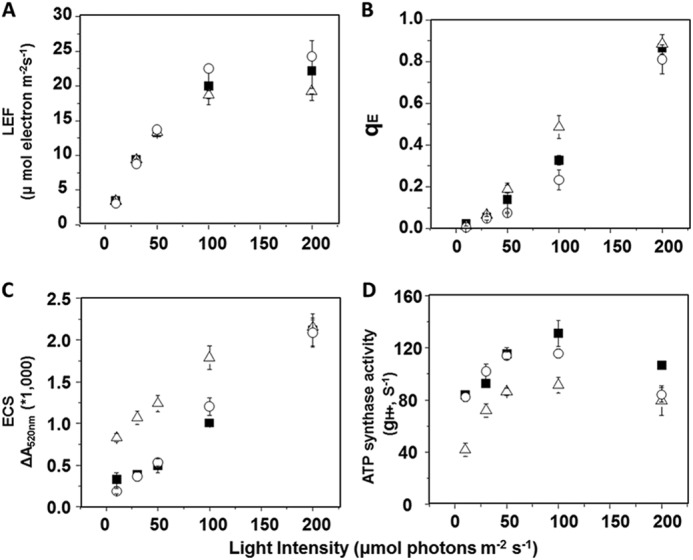

FIGURE 2.

Wild type (filled squares), a representative complemented line (35S::ATPC1 expressed in dpa1) (open circles), and mothra (open triangles) were compared for differences in light intensity-dependence of LEF (A), qE (B), light-induced pmf estimated by analysis of the electrochromic shift (ECSt) (C), and gH+ (D), based on first exponential ECS decay kinetics. Data are for attached leaves (n = 3).

The total amplitude of ECS signal in steady-state was used to assess the light-driven pmf across thylakoid membranes. Fig. 2C shows light-induced pmf responses under increasing actinic light. Wild-type and complemented lines showed similar pmf extents and light responses. The mothra mutant showed higher pmf responses at lower actinic light.

The relative activities of the ATP synthase, as estimated by the initial first-order exponential decay for the ECS signal (gH+) (for review, see Refs. 27, 32), were smaller in mothra than wild-type and complemented lines (Fig. 2D). Because lower ATP synthase activity results in slowing of proton efflux from the lumen, this effect can explain the higher pmf observed in mothra.

ATP Synthase in Mothra Is Equally Active in the Light- and Dark-adapted Leaves

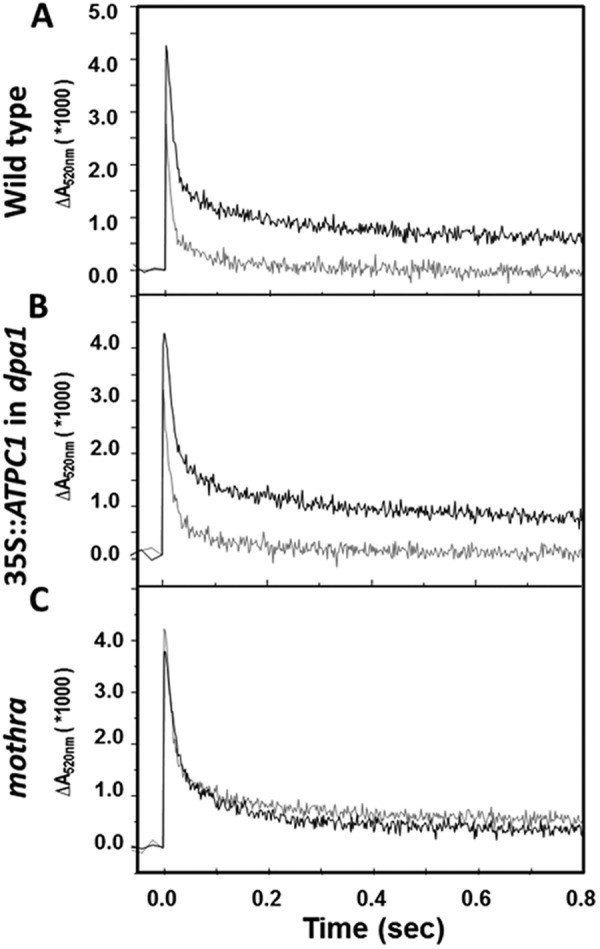

We analyzed ATP synthase activation state in attached leaves by probing the decay of the thylakoid pmf via the ECS signal after excitation with short (100 μs), nonsaturating light-emitting diode pulses. As discussed previously (15, 33), the decay of the ECS under these conditions is a good measure of the redox state of the γ subunit, i.e. the extent of the rapid phase is large when the γ subunit is reduced and slow when oxidized. Fig. 3A shows that preillumination of wild type for 2 min at 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 resulted in a large rapid ECS decay phase, indicating reduction of the γ subunit. Dark adaptation for 60 min led to reoxidization. The same response was observed in the complemented lines (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the modified γ-ATP synthase in mothra showed similar ECS decay kinetics in both light- and dark-adapted leaves, implying a lack of redox regulation. The extents of the fast and slow phases and thus the ATP synthase activity in mothra were intermediate between those seen in light- and dark-adapted wild type.

FIGURE 3.

Activity of the ATP synthase probed by the decay of the ECS signal. Flash-induced relaxation kinetics of ECS (15, 33) were measured for wild-type (A), complemented line (35S:: ATPC1 expressed in dpa1) (B), and mothra (C) at 1 min (gray curves) and 60 min (black curves) after 2-min preillumination at 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 actinic light.

ATP Synthase in Mothra Shows a Shifted γ Subunit Redox Midpoint Potential

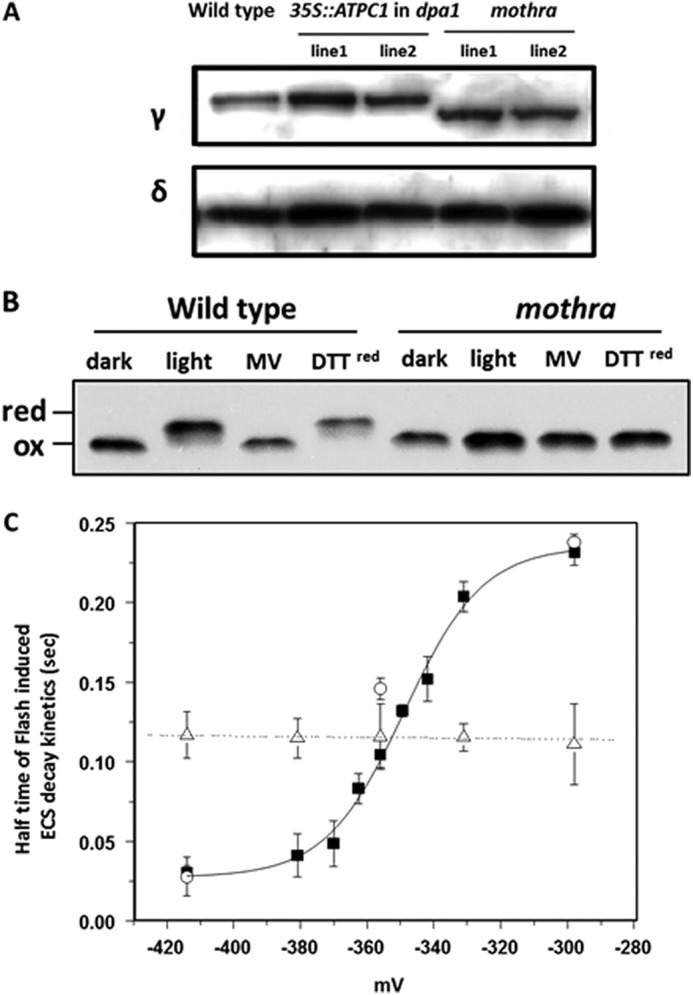

The γ subunit protein expression levels in two independent lines each of mothra, and the complemented lines were investigated by immunoblotting analyses against an antibody of the γ1 subunit (Fig. 4A). The γ1 subunit was highly expressed in the complemented line and mothra compared with wild type. Expression of ATP synthase δ subunit was constant. The apparent molecular weight of the mothra γ subunit was decreased compared with that of wild-type and the complemented lines, possibly due to effects of mutations on protein charge or secondary structure, e.g. the ability to form the regulatory disulfide bond.

FIGURE 4.

Accumulation and redox properties of chloroplast ATP synthase in wild type and mothra. A, accumulation of ATP synthase subunit γ and δ using Western blot analysis of thylakoid membrane proteins from wild type, representative complemented line (35S:: ATPC1 expressed in dpa1), and dpa1 complemented with modified ATPC1 (mothra). B, separation of reduced and oxidized γ subunits using AMS gel shift assay. To obtain reducing conditions (red), leaf discs were infiltrated with reagents and illuminated with ∼50 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Wild-type and mothra were treated with buffer as a control, methyl viologen (MV), and reduced DTT under light or dark condition. C, equilibrium redox titrations (18) of thiol/disulfide regulatory groups in the γ subunit of the chloroplast ATP synthase in wild type (filled squares), complemented line (35S:: ATPC1 expressed in dpa1) (open circles), and mothra (open triangles). The data for the wild-type titration were well fit with an n = 2 Nernst curve as expected for a disulfide/sulfhydryl transition. The ΔA520 relaxation kinetics were measured and used to calculate the halftime of the kinetics. Data represent the average ± S.D. (error bars) of n = 4–5.

The redox state of wild-type and mutant γ subunits was probed by modification of free sulfhydryl groups with AMS followed by separation on SDS-PAGE (16, 17). In wild type, the ATP synthase γ subunit showed the expected redox dependence upon exposure of dark-adapted leaves for 60 min to light, with the apparent molecular weight being completely shifted from low to high molecular weight, indicating transition from oxidized to reduced forms (Fig. 4B). Infiltration with methyl viologen blocked the transition to the reduced form, consistent with its ability to divert electrons from photosystem I electron acceptors to O2, thus preventing reduction of the γ subunit (15). Addition of reduced DTT mimicked the effects of light, consistent with its expected effects on thiol redox state. In contrast, the mothra γ subunit showed no response to light-induced reduction, as shown by the maintenance of a lower molecular weight band under light of DTT exposure (Fig. 4B), indicating that the mothra γ subunit is deficient in redox regulation in vivo.

We performed in situ equilibrium redox titrations using ratios of oxidized and reduced DTT and detected changes in activity by flash-induced ECS measurements (17, 18). The ATP synthase in wild type showed a transition from inactive to active at calculated ambient redox potential of about −350 mV, similar to results from previous work (17). In contrast, ATP synthase in mothra showed no substantial changes in activity over the entire range of redox potentials obtained by DTT, indicating that its redox potential is out of the range accessible by this method.

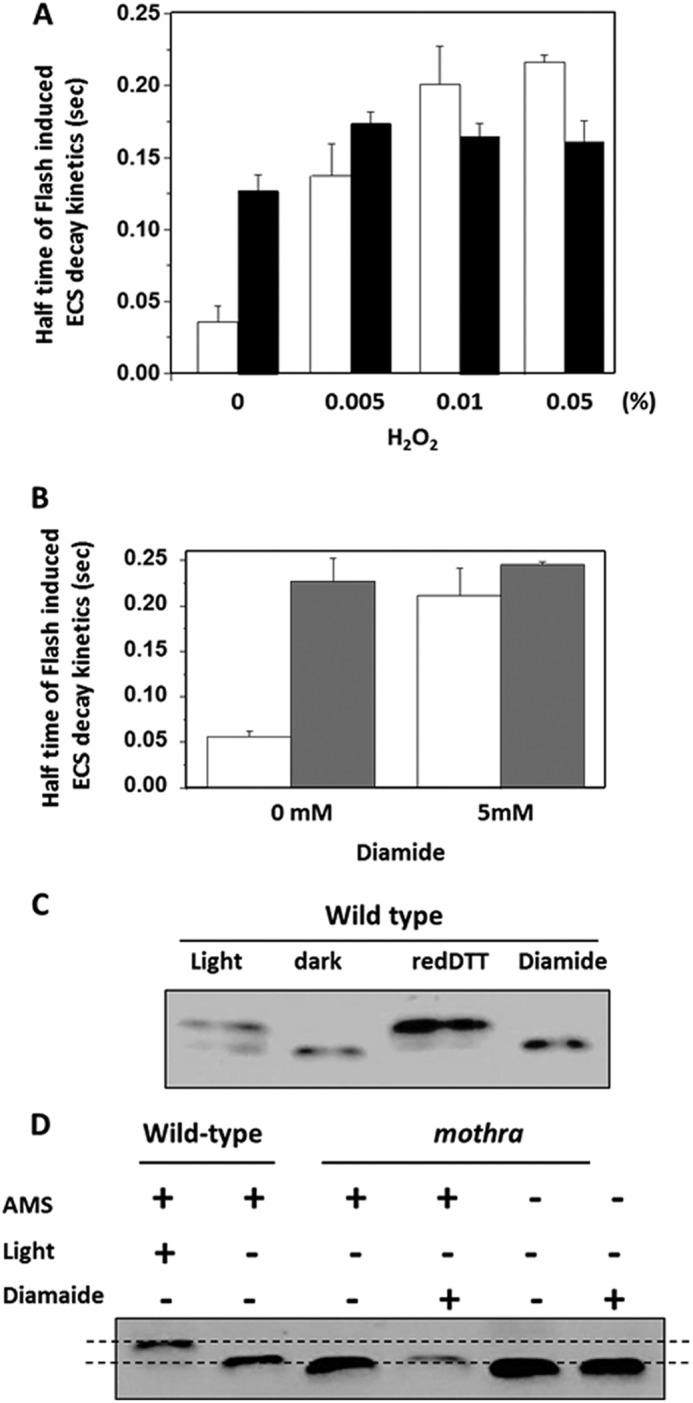

The lack of effect of redox potential on mothra ATP synthase could be caused by the γ subunit remaining in either the oxidized or reduced forms. Infiltration with strong oxidants H2O2 or diamide readily oxidized wild-type ATP synthase, as shown by ECS decay kinetics (Fig. 5, A and B) and AMS gel shift (Fig. 5, C and D) assays. In contrast, the ECS decay kinetics in mothra were insensitive to H2O2 and diamide and showed the same behavior as wild type in the presence of the two oxidants (Fig. 5, A and B). In addition, AMS had no significant effect on the apparent molecular weight of mothra γ subunit, likely indicating a lack of free sulfhydryl groups under any redox conditions tested, indicating a substantially higher redox potential, so that it remains in its oxidized form under physiological conditions.

FIGURE 5.

Modulation of ATP synthase activities and γ subunit structural properties by infiltration with strong oxidants. A, decay half-times of flash-induced ECS kinetics after preillumination, performed as described under “Experimental Procedures,” in leaf discs of wild-type (white bars) and mothra (black bars) infiltrated with buffer (20 mm Tricine-KOH, pH 7.5, 1% Tween 20) or a range of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentrations. B, leaf discs of wild type (white bars) and mothra (gray bars) infiltrated as in A, but with 5 mm strong oxidant diamide. C, control demonstrating the use of AMS gel shift assay for assessing modulation of γ subunit redox state in wild type under conditions described in Ref. 17. As indicated in the figure, wild-type leaf discs were vacuum-infiltrated with buffer as in A, during illumination with 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 or in darkness, reduced DTT, 5 mm diamide. Insoluble proteins were solubilized in sample buffer without addition of reducing regents, incubated in the thiol binding probe AMS, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Reduced proteins bands migrate less and appear in the upper part of the gel, whereas oxidized proteins migrate further (16, 17). D, AMS gel shift assay for redox state of wild-type and mothra γ subunit by light and diamide using the methods described for C. As a control, wild-type and leaf discs were treated with buffer in light (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1) or darkness, as described in Ref. 17. Leaf discs from mothra were treated with buffer and 5 mm diamide in the presence and absence of AMS labeling.

Metabolism-related Regulation of ATP Synthase in Wild Type and Mothra

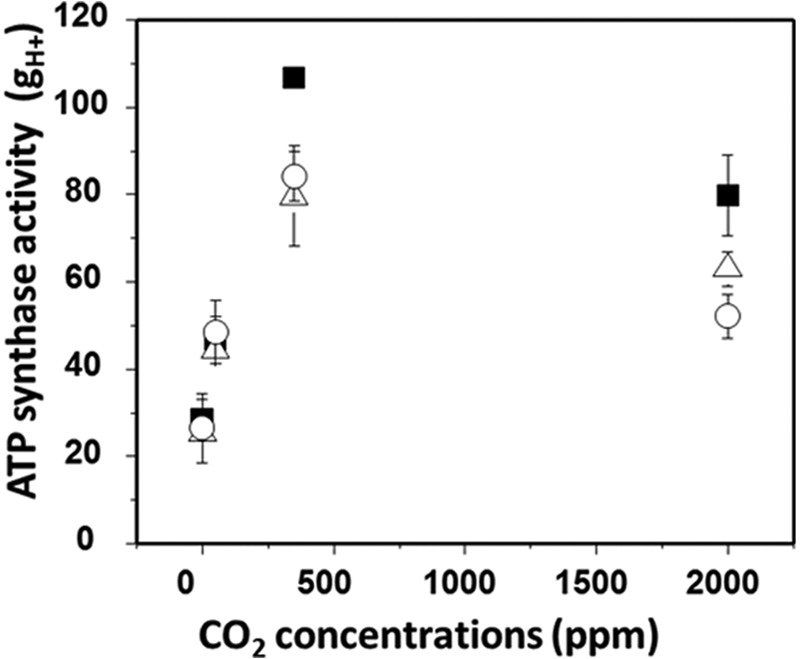

To test whether thiol modulation is responsible for metabolism-related ATP synthase regulation, we compared the responses of ATP synthase activity (measured as gH+) to CO2 levels in wild-type, mothra, and complemented lines with constant photosynthetically active radiation of 200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Fig. 6). The value of gH+ at ambient CO2 was approximately 25–30% higher in wild-type than either mothra or the complemented lines under all conditions, possibly reflecting slight differences in overall activity. However, decreasing CO2 levels from ambient to 50 or near 0 ppm resulted in similar, strong decreases in gH+ in all lines, quantitatively similar to the effects reported earlier for Arabidopsis (34), tobacco (20), or a range of C4 plants (22). Increasing CO2 to 2000 ppm also resulted in similar decreases in gH+ in wild-type, mothra, and complemented lines. This high CO2 effect was reported earlier and ascribed to feedback limitations related to depletion of stromal inorganic phosphate (22, 29). Overall, these results indicate that, whereas the ATP synthase in mothra is deficient in redox regulation, its responses to metabolic changes were essentially unaffected.

FIGURE 6.

Change in ATP synthase activity (gH+) from steady-state photosynthetic parameters in wild-type (filled squares), complemented line (35S::ATPC1 expressed in dpa1) (open circles), and mothra (open triangles) under 0, 50, 350, and 2000 ppm CO2 under 200 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Data are for attached leaves (n = 3–4).

DISCUSSION

Highly Conserved Acidic Amino Acid Residues Modulate the Redox Potential of ATP Synthase Regulatory Thiols

The γ subunit of the F0-F1-ATP synthase forms the central rotor of the ATP synthase (5, 7). The chloroplast homologue contains a novel regulatory domain, in which two redox-active cysteine residues are sandwiched between the long α helixes (7). It is now well established that these cysteine residues are reduced to free thiols by thioredoxin in the light and reoxidized in the dark, regulating the activity of the ATP synthase (for review, see Refs 19, 31). We found that mutating residues, Asp211, Glu212, and Glu226 to Val, Leu, and Leu, respectively, eliminated the classical light-dark regulation of the ATP synthase (Fig. 3), accompanied by a shift in the redox potential of the thiol/disulfide transition (Fig. 4), similar to the elimination of the regulatory cysteine residues (19). We conclude that these acidic residues are important for adjusting thiol redox properties. In another Arabidopsis mutant, cfq (18, 35), a single substitution of another highly conserved glutamate group (E244K) in the γ subunit resulted in more negative redox potential, rendering the complex more prone to oxidation in the dark. Deletion or mutation of the negatively charged residues Glu210-Asp211-Glu212 in this region in the thermophilic bacterium Bacillus PS3 (30, 31, 36) resulted in reverse redox sensitivity, i.e. becoming more active in the oxidized form and less in the reduced. We thus conclude that redox potential and its effects on activation of the ATP synthase are highly dependent on the charges and overall conformation of this regulatory loop. These suggest that the thiol modulation in chloroplast ATP synthase is highly dependent upon the structure of the γ subunit, particularly because it revealed that acidic amino acids in the regulation domain induce smooth transition to reduced state.

Physiological Consequences of Altered Thiol Modulation in Mothra

The chloroplast ATP synthase is controlled by the interplay of pmf and redox modulation (15, 37). In the light, the γ subunit is reduced by thioredoxin, causing the ATP synthase to be activated when pmf reaches a relatively low threshold level. Because this low pmf is close to that sustained by ATP hydrolysis in the dark, the ATP synthase remains activated in the dark (15). Oxidation of the γ subunit in the dark imposes a higher activation threshold for ATP synthase leading to inactivation, presumably to prevent wasteful hydrolysis of ATP in the dark. These regulatory behaviors are clearly seen in Fig. 3, where the decay of the ECS signals in light-adapted wild type (with reduced ATP synthase) was monotonic, reflecting a continuously active ATP synthase. After dark adaptation, ECS decay underwent a sharp transition from fast to slow, when pmf decreased below the activation threshold. In mothra, ECS decay kinetics remained biphasic in both light- and dark-adapted leaves, implying that the ATP synthase activity was redox-insensitive. Moreover, ECS decay kinetics in mothra appeared intermediate between those of light- and dark-adapted wild type, suggesting that the mutant enzyme was locked in a partially activated state.

The differences in ATP synthase regulation and activities have consequences for steady-state photosynthesis. The inability to fully activate the ATP synthase in mothra results in lower steady-state proton conductivity (gH+, Fig. 2D). The effects were especially pronounced at low irradiance where gH+ was 50% of that of wild type, as expected from the requirement for additional pmf to fully activate ATP synthase in mothra. The lower gH+ slows the release of protons from the thylakoid lumen, increasing light-driven pmf (Fig. 2C). Above 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, where feedback regulation of the light reactions is engaged, the increased pmf in mothra results in stronger activation of the qE response (Fig. 2B) and slowing of LEF (Fig. 2B).

We did not observe substantial differences in cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in wild type and mothra as estimated by two methods: redox state of photosystem I by 820 nm absorbance changes of P700 and proton flux by ECS (data not shown), indicating that the differences in the relationship between pmf and LEF can be attributed to altered activity of the chloroplast ATP synthase (see discussion in Refs. 27, 28). Thus, whereas regulation of light capture was altered by the mutations, the overall ATP/NADPH output ratio was largely unaffected.

Thiol and Metabolism Modulation of the ATP Synthase Activity Is Mechanistically and Functionally Distinct

ATP synthase is regulated under steady-state illumination in response to metabolic status, e.g. in response to changing CO2, O2, or mutations that affect assimilation (20, 22, 27). This metabolism-related regulation modulates the thylakoid pmf (27, 29), thus affecting the regulation of light capture and subsequent electron transfer. The mechanism of the metabolism-related regulation is not known, but one possible model would involve thiol modulation. To test this possibility, we used mothra, which shows redox-insensitive ATP synthase activity, with only small effects on sustained photosynthesis at growth light irradiance (Fig. 2). Although the basal rate of ATP synthase in mothra was somewhat lower than in wild type, altering CO2 levels had nearly identical effects on ATP synthase activity in vivo in wild type and mothra (Fig. 6), indicating that, although mothra-ATP synthase was defective in light-dark regulation, it retained its capacity for metabolic fine-tuning. We thus conclude that metabolism-related regulation of ATP synthase does not involve thiol modulation of the γ subunit. This result is consistent with previous observations that thiol activation of the ATP synthase occurs at very low irradiances and thus likely acts as an on-off switch to activate the complex at very early times during induction of photosynthesis (15, 33). The binding of substrates (ADP or Pi) (27, 29, 38, 39) or allosteric effectors or covalent modification (e.g. phosphorylation) (40–42) are most likely fine-tuning effectors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jeffrey A. Cruz and Atsuko Kanazawa for stimulating discussions; Robert Zegarac and Mio Sato-Cruz for expert advice and assistance with the instrumentation and experiment, respectively; and Dr. Richard J. Berzborn (Ruhr-Universität Bochum) for the CF1-γ and δ antibodies.

This work was supported by United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences Program DE-FG02-91ER20021 (to K. K. and D. M. K.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to C. D. B.), and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB TR1) (to J. M.).

- ATP synthase

- chloroplast CF0-CF1-ATP synthase

- AMS

- 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonate

- ECS

- electrochromic shift

- gH+

- conductivity of thylakoid membrane to protons

- LEF

- linear electron flow

- mothra

- modified thioredoxin-regulated ATP synthase

- pmf

- proton motive force

- qE

- energy-dependent exciton quenching

- 35S

- cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Junesch U., Gräber P. (1991) The rate of ATP-synthesis as a function of ΔpH and Δψ catalyzed by the active, reduced H+-ATPase from chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 294, 275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seelert H., Dencher N. A., Müller D. J. (2003) Fourteen protomers compose the oligomer III of the proton-rotor in spinach chloroplast ATP synthase. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 337–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jonckheere A. I., Smeitink J. A., Rodenburg R. J. (2012) Mitochondrial ATP synthase: architecture, function and pathology. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 35, 211–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okuno D., Iino R., Noji H. (2011) Rotation and structure of F0F1-ATP synthase. J Biochem. 149, 655–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abrahams J. P., Leslie A. G., Lutter R., Walker J. E. (1994) Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370, 621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cross R. L., Nalin C. M. (1982) Adenine nucleotide binding sites on beef heart F1-ATPase: evidence for three exchangeable sites that are distinct from three noncatalytic sites. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 2874–2881 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Richter M. L., Samra H. S., He F., Giessel A. J., Kuczera K. K. (2005) Coupling proton movement to ATP synthesis in the chloroplast ATP synthase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37, 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Groth G., Strotmann H. (1999) New results about structure, function and regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase (CF0CF1). Physiol. Plant. 106, 142–148 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richter M. L. (2004) γ-ϵ Interactions regulate the chloroplast ATP synthase. Photosynth. Res. 79, 319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Evron Y., Johnson E. A., McCarty R. E. (2000) Regulation of proton flow and ATP synthesis in chloroplasts. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 32, 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hisabori T., Konno H., Ichimura H., Strotmann H., Bald D. (2002) Molecular devices of chloroplast F1-ATP synthase for the regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1555, 140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hisabori T., Ueoka-Nakanishi H., Konno H., Koyama F. (2003) Molecular evolution of the modulator of chloroplast ATP synthase: origin of the conformational change-dependent regulation. FEBS Lett. 545, 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mills J. D., Mitchell P. (1982) Modulation of coupling factor ATPase activity in intact chloroplasts: reversal of thiol modulation in the dark. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 679, 75–83 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ort D. R., Oxborough K. (1992) In situ regulation of chloroplast coupling factor activity. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 269–291 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kramer D. M., Crofts A. R. (1989) Activation of the chloroplast ATPase measured by the electrochromic change in leaves of intact plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 976, 28–41 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Konno H., Nakane T., Yoshida M., Ueoka-Nakanishi H., Hara S., Hisabori T. (2012) Thiol modulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase is dependent on the energization of thylakoid membranes. Plant Cell Physiol. 4, 626–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohzuma K., Dal Bosco C., Kanazawa A., Dhingra A., Nitschke W., Meurer J., Kramer D. M. (2012) Thioredoxin-insensitive plastid ATP synthase that performs moonlighting functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 3293–3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu G., Ortiz-Flores G., Ortiz-Lopez A., Ort D. R. (2007) A point mutation in atpC1 raises the redox potential of the Arabidopsis chloroplast ATP synthase γ subunit regulatory disulfide above the range of thioredoxin modulation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36782–36789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu G., Ort D. R. (2008) Mutation in the cysteine bridge domain of the γ subunit affects light regulation of the ATP synthase but not photosynthesis or growth in Arabidopsis. Photosynth Res. 97, 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avenson T. J., Cruz J. A., Kramer D. M. (2004) Modulation of energy-dependent quenching of excitons in antennae of higher plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5530–5535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kohzuma K., Cruz J. A., Akashi K., Hoshiyasu S., Munekage Y. N., Yokota A., Kramer D. M. (2009) The long-term responses of the photosynthetic proton circuit to drought. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kiirats O., Kramer D. M., Edwards G. E. (2010) Co-regulation of dark and light reactions in three biochemical subtypes of C4 species. Photosynth. Res. 105, 89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Livingston A. K., Cruz J. A., Kohzuma K., Dhingra A., Kramer D. M. (2010) An Arabidopsis mutant with high cyclic electron flow around photosystem I (hcef) involving the NADPH dehydrogenase complex. Plant Cell 22, 221–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Livingston A. K., Kanazawa A., Cruz J. A., Kramer D. M. (2010) Regulation of cyclic electron flow in C plants: differential effects of limiting photosynthesis at ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Plant Cell Environ. 33, 1779–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Plant J. 16, 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dal Bosco C., Lezhneva L., Biehl A., Leister D., Strotmann H., Wanner G., Meurer J. (2004) Inactivation of the chloroplast ATP synthase γ subunit results in high nonphotochemical fluorescence quenching and altered nuclear gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1060–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanazawa A., Kramer D. M. (2002) In vivo modulation of nonphotochemical exciton quenching (NPQ) by regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12789–12794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cruz J. A., Avenson T. J., Kanazawa A., Takizawa K., Edwards G. E., Kramer D. M. (2005) Plasticity in light reactions of photosynthesis for energy production and photoprotection. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 395–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takizawa K., Kanazawa A., Kramer D. M. (2008) Depletion of stromal Pi induces high “energy-dependent” antenna exciton quenching qE by decreasing proton conductivity at CF0-CF1 ATP synthase. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konno H., Yodogawa M., Stumpp M. T., Kroth P., Strotmann H., Motohashi K., Amano T., Hisabori T. (2000) Inverse regulation of F1-ATPase activity by a mutation at the regulatory region on the γ subunit of chloroplast ATP synthase. Biochem. J. 352, 783–788 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hisabori T., Sunamura E. I., Kim Y., Konno H. (2013) The chloroplast ATP synthase features the characteristic redox regulation machinery. Antioxid. Redox Signal., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baker N. R., Harbinson J., Kramer D. M. (2007) Determining the limitations and regulation of photosynthetic energy transduction in leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1107–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kramer D. M., Wise R. R., Frederick J. R., Alm D. M., Hesketh J. D., Ort D. R., Crofts A. R. (1990) Regulation of coupling factor in field-grown sunflower: A Redox model relating coupling factor activity to the activities of other thioredoxin-dependent chloroplast enzymes. Photosynth. Res. 26, 213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takizawa K., Cruz J. A., Kanazawa A., Kramer D. M. (2007) The thylakoid proton motive force in vivo: quantitative, noninvasive probes, energetics, and regulatory consequences of light-induced pmf. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1233–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gabrys H., Kramer D. M., Crofts A. R., Ort D. R. (1994) Mutants of chloroplast coupling factor reduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 104, 769–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ueoka-Nakanishi H., Nakanishi Y., Konno H., Motohashi K., Bald D., Hisabori T. (2004) Inverse regulation of rotation of F1-ATPase by the mutation at the regulatory region on the γ subunit of chloroplast ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16272–16277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Junesch U., Gräber P. (1987) Influence of the redox state and the activation of the chloroplast ATP synthase on proton transport-coupled ATP synthesis hydrolysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 893, 275–288 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sharkey T. D., Vanderveer P. J. (1989) Stromal phosphate concentration is low during feedback limited photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 91, 679–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sharkey T. D., Vassey T. L. (1989) Low oxygen inhibition of photosynthesis is caused by inhibition of starch synthesis. Plant Physiol. 90, 385–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bunney T. D., van Walraven H. S., de Boer A. H. (2001) 14-3-3 protein is a regulator of the mitochondrial and chloroplast ATP synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4249–4254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reiland S., Messerli G., Baerenfaller K., Gerrits B., Endler A., Grossmann J., Gruissem W., Baginsky S. (2009) Large-scale Arabidopsis phosphoproteome profiling reveals novel chloroplast kinase substrates and phosphorylation networks. Plant Physiol. 150, 889–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. del Riego G., Casano L. M., Martín M., Sabater B. (2006) Multiple phosphorylation sites in the β subunit of thylakoid ATP synthase. Photosynth. Res. 89, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]