Abstract

This qualitative research project explores how poverty, the built environment, education, working conditions, health care access, food insecurity and perceived discrimination are experienced by Puerto Rican Latinas through the course of their lives. Five focus groups were conducted with the primary objective of documenting community experiences and perspectives regarding: 1) stress, including perceived discrimination based on race/ethnicity (racism); 2) the impact of stress on Puerto Rican women of reproductive age, their families, and/or their community; and 3) stressors that affect maternal health. Focus groups were conducted in English and Spanish in the two cities with the highest rates of premature birth and low infant birthweight in the state of Connecticut. Focus group findings indicate that participants perceived poverty, food insecurity, lack of access to quality education, and unsafe environments as significant life stressors affecting maternal and child health.

Keywords: Puerto Ricans, social determinants of health, discrimination, education, food insecurity, environment, maternal health, stress

Stressful life events, including financial difficulties, food insecurity, lack of social support and discrimination, among others, have been associated with adverse health outcomes.1–5 Many of these stress-related health outcomes represent neuro-endocrine, immune, and vascular physiological responses to stressors over the life course.1,6–8 Maternal stress and elevated prenatal cortisol have been associated with several negative conditions including prematurity and low birthweight.9–11 Cortisol interacts with neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, which may cause premature birth.11 Most studies on stress and birth outcomes have been conducted among African American women.12–18

Excessive stress exposures during the life course have been demonstrated to have an impact on birth outcomes. It is well documented that highly threatening situations during childhood may generate stress-induced emotional and physiological health consequences, including poor birth outcomes among African American women.19–20

To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined the possible link between stress during the life course and maternal health among Latinas. This knowledge gap has strong implications for Puerto Rican women, as they have the highest incidence of premature delivery among Latinas. Thus, it is essential to conduct community-based participatory research (CBPR) studies to identify the perceived social determinants of stress among Puerto Rican women.

The primary goal of this study was to understand better the life course social determinants of health experienced by Puerto Rican women with emphasis on those that are likely to affect maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Thus, this study focuses on 1) experiences with self-perceived discrimination based on race/ethnicity (racism), poverty, food insecurity, education, health care access and treatment, the physical environment, and working conditions; and 2) the possible perceived impact of stress on the health of Puerto Rican women themselves as well as on the well-being of their families and communities.

Based on the socio-ecological model our key a priori assumption was that the stressors experienced individually by women would be a manifestation of the lack of social capital in their communities and how it affects the household physical and psycho-emotional environment.

Why Puerto Rican Latinas?

Latinos constitute the largest racial/ethnic minority population in the U.S. Among Latinos, Puerto Ricans experience higher levels of poverty and poor health outcomes than the average levels for Latinos.21 Puerto Rican women have the highest incidence of premature delivery and low infant birthweight and experience higher infant mortality rates than other Latina sub-groups.22–31 Infant mortality, low birthweight, and pre-term delivery rates increased during the 1990s among Puerto Rican children born in the continental U.S. Between 1989 and 2000, low birthweight rates increased from 8.9% to 9.3% in this ethnic group.25 In 2007, the infant mortality rate among Puerto Rican children was 7.99 per 1,000 live births, compared with 5.87 for Mexican, 4.59 for Cuban, and 3.24 for infants of Central and South American descent.32

In Connecticut, where the majority of Latinos identify themselves as Puerto Rican, the rate of preterm births increased by 3% between 1997 and 2007.29 In 2007 there were 4,371 preterm births in the state, representing 10.5% of live births.29 Preterm birth rates in the state were highest among Black infants (14.5%), followed by Latinos (11.0%), Whites (9.5%), Native Americans (8.5%) and Asians (8.8%).29

In four of the eight Connecticut counties (New Haven, Hartford, New London, and Windham) over half of their Hispanic population is Puerto Rican. Within those counties, Latinos experience higher rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes than non-Hispanic Whites.29

Social determinants of health

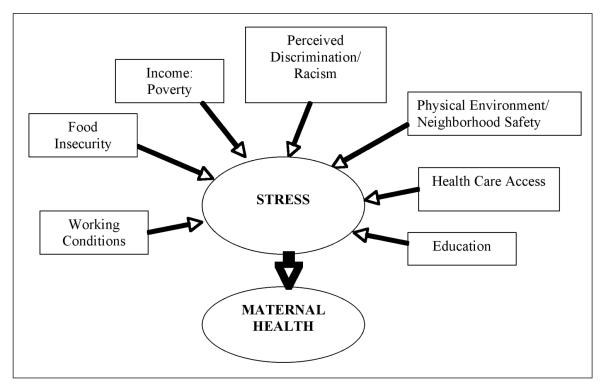

Social determinants of health are defined by the World Health Organization as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system.33 These societal conditions, which often affect health, can be changed by social and health policies and programs.34 Studies have documented the link between lower socio-economic status, poor education, poor housing and/or neighborhood quality, poor working conditions, lack of quality medical care, and poor health status.35 Women who have not finished high school are more likely to give birth to a premature or low birthweight baby than those who have college degrees.36 There are interactions among race, socio-economic status, and health outcomes.36–37 The theoretical framework for this study makes the social determinants of health central (Figure 1).36–37

Figure 1.

Social determinants of stress.

Methods

Between February and April, 2009, we conducted five focus groups among 29 Puerto Rican women of reproductive age in the cities of Hartford and Willimantic. To be included, women had to self-identify as Puerto Ricans and be 18 years or age or older. Participants were assigned to the focus groups according to their age group category and pregnancy status. In Hartford, three focus groups were conducted at the Hispanic Health Council: one with non-pregnant women 18 and 21 years old, one with non-pregnant women between the ages of 22 and 35 years, and the third with pregnant women 18 years and older. In Willimantic, two focus groups were conducted at a local elementary school and at a community center in a housing complex where the majority of tenants are of Puerto Rican descent. One focus group was conducted with non-pregnant women between the ages of 18 and 21 years and the second with non-pregnant women between the ages of 22 and 35. While the focus groups with non-pregnant women from 18 and 21 years of age were conducted in English while the rest were conducted in Spanish, since previous research has documented that younger Puerto Rican women are more likely to be bilingual and primarily speak English.38

Participants were recruited through culturally appropriate community outreach conducted by bicultural and bilingual research staff. Recruiters were trained on the study objectives and design and on understanding likely barriers for study participation and effective ways to address them. All study materials including screening forms, informed consent forms, questionnaires, and flyers were translated into Spanish. The research staff was also trained on how to build rapport with the local Latino community agencies and apartment complex managers to assist with recruitment.

Participants were recruited through referrals by community agencies in each local area and street outreach in neighborhoods densely populated by Puerto Ricans. During recruitment, participants were screened for eligibility by telephone or face-to-face and, if they qualified, were invited to participate in a focus group. Approximately 12 to 15 participants were targeted and invited to participate in each focus group. Based on our previous experiences conducting focus groups with the target population we expected that this approach would yield six to 10 participants per group, which falls within the recommended sample size for focus group sessions.39

On the day of the focus group, after again hearing a description of the study, prior to any data collection eligible participants read, signed, and received a copy of the informed consent form. Childcare and refreshments were provided at each focus group session. Focus groups lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours and participants received a monetary incentive for their participation. The Hispanic Health Council Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data collection

After providing informed consent, participants completed a brief socio-demographic information sheet. The information collected included age, language of preference, number of years living in the United States, ethnicity, income, education level, marital status, and health insurance status. Participants also provided information about their perceived experience with discrimination, the quality of medical treatment they have received to date and the type of health insurance they have.

The focus group guide included closed and open-ended questions about the social determinants of stress. Participants were asked a series of questions about perceived stress and stressors (Box 1). The questions intended to engage the women first to speak freely about themes that were related to stressors. For example, women were asked, In your own words, what is stress? How does stress affect people? and What causes stress? These general questions were then followed by questions on specific conditions that we had previously identified as being prevalent in their communities and that are likely to be a source of stress in their households and communities.

Box 1.

Each focus group was staffed by one facilitator, one co-facilitator, and one or two note-takers. The facilitator and note-taker(s) were of Puerto Rican descent. Focus groups were audio-taped and subsequently transcribed verbatim. All questions in the focus group guide were written on an easel pad for participants to refer to during the discussion. During the focus group sessions, the facilitator read each question and followed a script with prompts for probing in order to make sure important points were fully discussed. The notes taken during each focus group were used during de-briefing sessions. In these sessions, the facilitator, co-facilitator, and note-taker discussed the interpretation of the questions, participants’ key points, number of participants expressing the same key point and participants’ non-verbal activity (nodding of the head, eye contacts, level of agreement, disagreement, and interest).

After the completion of the first focus group, the facilitator and co-facilitator made minor changes to the questions in the discussion guide, for subsequent groups better to capture issues missed in the first group.

Data entry and analyses

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 (IBM Corporation, Somers, New York) was use to analyze participants’ socio-demographic characteristics.40 Chi-squared cross-tabulation analyses were used to compare socio-demographic variables across focus groups. Results were considered significant at p<.05.

Extensive notes were taken at each focus group by a bilingual/bicultural interviewer. In addition, focus groups sessions were transcribed verbatim by an accredited transcription service company. Focus groups conducted in Spanish were translated into English. A bilingual/bicultural investigator and the study principal investigator reviewed each translated transcript for accuracy. Transcripts were read by an interdisciplinary research team of seven coders with expertise in epidemiology, public health, social work, nutrition, and cultural anthropology. The team included bilingual and bicultural investigators, following a systematic analysis approach.41 This process started with the first focus group and continued past the last focus group. At the end of each focus group the moderator offered a brief summary of key findings to participants and inquired if the summary was correct. During each focus group, a diagram of seating arrangements was drawn. After each focus group, a debriefing session with the moderator, co-moderator and note takers took place. At the de-briefing sessions the following items were discussed: 1) key themes, ideas, and interpretation; 2) what was surprising; 3) how did the group compared with the previous focus group; and 4) if there were any changes needed to be done before the next group. After transcripts were received and reviewed, each focus group was analyzed by the interdisciplinary research team. This interdisciplinary research team reviewed the transcripts, identified emerging themes for each question, provided comments and feedback about the content and main findings of each focus group, developed codes and sub-codes, integrated the findings, and identified quotes to illustrate main findings. Each analysis continued until no new themes were identified indicating that information saturation had been attained.41 ATLAS.ti version 6 qualitative data analyses software was used to code and organize the data for analysis.22,39 Results are presented using direct quotations extracted from the text to document the key findings.39,42

Results

Participants characteristics

Participants’ mean age was 25±5.7 yrs. They were predominantly single, low-income, and unemployed, and had little education (Table 1). When participants were asked if they thought the health care system treats people unfairly because of their race or ethnicity; 41.4% answered never, 31% rarely, 20.7% sometimes, and 3.4% always. When asked if they thought the health care system treats people unfairly because of the type of health insurance they have, 34% answered never, 17.2% rarely, 24.1% sometimes, 17.2% often, and 3.4% always.

Table 1.

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS (N=29)

| 25±5.7 yrs |

||

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | n | % |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single (never married, not living together) | 21 | 72.4 |

| Married/living together | 8 | 27.6 |

| Primary Language (s) Spoken at Home | ||

| English | 2 | 6.9 |

| Spanish | 13 | 44.8 |

| English and Spanish equally | 14 | 48.3 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Middle school (grade 6–8) | 1 | 3.4 |

| Some high school, no diploma | 13 | 44.8 |

| High school graduate or GED | 9 | 31.0 |

| Technical or vocational school | 1 | 3.4 |

| Some college | 5 | 17.2 |

| Employment Status (n=28) | ||

| Employed | 4 | 14.3 |

| Unemployed | 24 | 85.7 |

| Household Income | ||

| 0 to <$500 | 17 | 58.6 |

| $500–$999 | 3 | 10.3 |

| $1,000 and above | 5 | 17.2 |

| Don’t know | 4 | 13.7 |

| Health Insurance Status | ||

| Yes | 23 | 79.3 |

| No | 5 | 17.2 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 3.4 |

| Type of Health Insurancea | ||

| Medicaid/SAGA | 6 | 30.0 |

| Medicaid (Title 19/Husky) | 12 | 60.0 |

| Medicare | 1 | 5.0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 5.0 |

Data only available for 20 participants.

There were no significant differences in participants’ characteristics across focus groups with regard to amount of time living in the U.S., primary language, marital status, health insurance status, and income levels. Significant differences were seen in education and employment status. Individuals who participated in the focus groups conducted in Willimantic had more educational attainment than their Hartford counterparts. Consistent with this finding, Willimantic participants were also more likely to be employed part or full time.

Focus group findings

Content analyses of the focus groups revealed three main themes related to stress: (1) definition of perceived stress, (2) social determinants of stress, and (3) consequences of stress related to maternal health.

Definitions of perceived stress

Participants defined stress as many emotions combined, a negative feeling, inability to stay focused or eat, and loss of hope: Stress like … a negative feeling to me; Stress is when you are not able to stay focused or eat … ; Stress is … when things don’t go well, and you reach a point that you don’t know if looking left or right …

Social determinants of stress

Most women identified the causes of stress as being associated with social determinants of health: Stress is when you don’t have a job … you can’t support your family … and knowing that your child is in need, of you know, supplies like diapers, clothes, medicine … and you just constantly think about it; In my opinion stress is … when you have problems with your kids in the school and you can’t find the support from the teachers or the school principal; when you don’t have enough Food Stamps and you constantly worry what are we gonna eat today … I stress about it a lot.

Income/poverty

Focus group participants reported inadequate income to meet their basic needs and lack of social and financial support as well as unemployment as common stressors. An 18 year-old participant discussed that her family constantly moved during her childhood due to difficulties paying rent, electricity, and heating bills: … my family were constantly moving just because of the job you know, we couldn’t pay the apartment and then the landlord … constantly knocking at the door so in winter they would disconnect the heater and the light so we wouldn’t have heater or light in winter so its stressing you know …

Prioritizing how to spend money in the face of poverty emerged as an important topic. Participants often noted that they pay the rent first, then car insurance so they can go to work, then food, and then they divide what is left to pay the rest of the bills: … I mean, I have to think about the rent, I have to think about the insurance, I have to think about the food and … if there is money left I have to divide it … I have to buy him his school equipment also, because I do not have any help for that.

Unemployment was considered a source of stress. One participant said, And the economy is not too good, just to find a job and you just wake up in the morning, 7:30 in the morning just to start looking for a job, by the end of the day by 2, 3 o’clock you don’t have, um [sucks teeth] you don’t have … like uh um like any [sigh] like como ganas [the desire anymore] …

Lack of social support

Raising children as single mothers was a stress: I am a single mom and I’m pregnant, sometimes you don’t have money for what they [the children] need…. Another participant reported being unable to count on family to help her when she needs it: … but when you need them … you want to talk to somebody or when you are in need of a favor they are limited. ‘Oh, I can’t do this, oh you know I’m busy, or I can’t come and visit.’ That’s a lot of stress …

Poor educational system

When asked to discuss education as a stressor, focus group participants articulated the following concerns as the main problems with the school system: a) very poor quality of education; b) lack of important resources for learning; and c) school safety.

a) Very poor quality of education. Participants stated that the quality of education their children receive is not equal to education provided in other places. They also commented, based on their own schooling experience, that teachers are often not engaging students in learning.

Participants talked about how their financial situation prevents them from transferring their children to a better school district: … if I can remove my kid from Hartford for his education, I will do it; I think … if they want a good thing for their kids, they should move and put their kids in another school system.

Most participants also felt that college education was not an attainable or reachable goal for most students in their communities:

The elementary schools do not offer a good education for our children, how are they going to even make it to, to middle school?

I said that if my child stays here in Hartford middle school, he’s not going to want to go to high school.

… is easy to be a dentist assistant, nurse assistant, and assistant for everything but is very difficult to be a doctor.

b) Lack of important resources for learning. Women expressed concerns such as … the children’s desks are broken … the books are broken … hello, what’s going on?

c) School safety. Participants talked about the violence in the schools and their lack of trust in the security staff. They were also concerned about bullying: … My kid was new in the middle school, there was another kid … looking for problems with my kid. I went to the office and they did nothing, I had to talk to the other kid, because they [referring to the school] did nothing …

Food insecurity

Food insecurity is defined as the limited ability to acquire nutritionally adequate and safe foods in socially acceptable ways.43 Focus group participants reported food insecurity experiences since childhood: … when we were growing up … we used to tell each other don’t eat too much we have to save that for next week; If I stayed home I was only going to eat one time, then I will stay hungry, so … I never missed school because they offered lunch, I was the first one at the lunch line.

Food insecurity was reported to be a powerful stressor: It’s a stress to have to think for tomorrow what you are going to eat when there is nothing in the refrigerator; Well, you have to feed your children first and you’re pregnant and you don’t have nothing else to feed yourself; if your kids ask for something, ‘Oh, I want a snack for school’ and you don’t have the money to afford, Food Stamps or whatever. It is stressful.

Women also felt that the food assistance programs, such as WIC and SNAP helped but did not provide enough to feed the family for the entire month: … to her [referring to her daughter who received WIC] they give her juice, cereals, cheese, beans … but I have three more and I have to divide the milk between four; you know the Food Stamps do not last the whole month; I have seen myself at the end of the month with no groceries, with nothing …

Participants had a difficult time accessing healthy foods: … We didn’t have any food at home, we had to buy the fastest thing (closer to home) … for two months we were eating junk food from fast food restaurants …; I was trying to maintain … wheat bread, fruit, but a moment comes in that you say look I hang up the gloves because I cannot [afford it] …

Unsafe physical environment

Participants discussed their own experiences and their fear of letting their children play outside because of worries about child rape, kidnapping, and exposure to violence: … another thing too, that when you live around this area, there’s a lot … of drug movement … This is a very bad area for someone to walk alone … there is always fights, shootings, and that bullet has no name.

Mothers talked about the stress of having to explain street violence to their children: … then how you gonna explain your child, how you going to sit there … and explain to your child if they’ve seen somebody with a needle in their arm, it’s to say somebody killed, somebody died, that’s another stress … .

Participants talked about their fear of collaborating with authorities because they and/or their families might become targets, but also articulated the importance of reporting these incidents.

Other social determinants of stress

Although perceived discrimination/racism, and lack of health care access and treatment were not directly identified as main stressors among most participants, their experiences suggested that some had experienced discrimination: Like every time I go to … the mall to a store and you see that they are hiring because they have the paper outside but when you go in, they said to you they are not, they don’t accept applications … there are people that are … racists and don’t care, do you understand me?

The limitation of not having health insurance was a stressor, preventing participants from going to the doctor when feeling ill: … But I mean it’s nice to feel that you have insurance cause me, personally, I’m always sick, like, I’m always feeling like I know there is something wrong with me and I want to go get checked, but I can’t ‘cause I don’t have insurance.

Consequences of stress related to maternal health

The majority mentioned how stress affects their mental health: You don’t think right, … you just constantly … just step up to a mirror and look at yourself and think, what, like, like, who am I? like who am I looking at? am I looking at myself or am I looking at somebody [else]? Participants reported that they cry a lot when they are stressed. One woman commented on depression: … stress has really caused a history of depression in my family … as a result my mother has depression, my sister … she is worried about my mom, for her health, also acquired depression; … my problems, I have depression, not for worrying about her but because of my things, well we all have depression and its like a chain …. One participant described her experience with co-workers and how the stress of poverty caused one to have suicidal thoughts and another to prostitute herself.

Participants also mentioned experiencing poor physical health symptoms when they are stressed: I get chest pain when I’m stressing out; You can develop a lot of things when you’re under stress, I have alopecia; When I’m stressed and have problems well, I get skinny …

Discussion

Our findings showed that low-income Puerto Rican women experienced described stress as an emotional consequence of many social/environmental factors. And that stress in turn affects their health and wellbeing. As social conditions worsen, so does health.44 In this study, it was evident that stress was prevalent among participants and that this affected their mental health and physical health. Participants expressed the feelings of giving up and losing hope because of their social conditions. A study conducted with Puerto Rican patients who arrived at a city hospital emergency room because they had attempted suicide found that hopelessness was correlated with suicidal intent.45

Participants reported experiencing chest pain, anxiety, dizziness, headaches, increased blood pressure, hair loss and decreased weight and depression as health problems caused by the stress in their lives. Previous studies have associated stressful life events including financial difficulties, food security, lack of social support, and discrimination with adverse health outcomes.1–5

Focus group participants reported past (including childhood) and present food insecurity. Women from food-insecure households have higher measures of adverse psychological states (perceived stress, depression symptoms, and anxiety) than women who are food-secure.46 Consistent with these findings, a previous study conducted by our research team in Hartford found that pregnant women who were food-insecure were more likely than food-secure women to experience elevated levels of prenatal depressive symptoms.47 Chronic stress caused by constrained economic resources and subsequent limited access to food could contribute to feelings of helplessness and distress during pregnancy, and subsequent symptoms of stress and depression.48–49

In our study, participants discussed how stressful it was to live in poverty, in a high crime neighborhood, exposed to violence and drug use, in fear of speaking out to the authorities and without resources to move to a safer place. This in turn may have explained their perception of lack of social support event from their families. The place where people live is a predictor of health.43 Lifelong exposure to these stressors can all contribute to unfavorable birth outcomes since several studies have found an association between neighborhood poverty and low infant birthweight.14,49–51,52

Furthermore, our results highlight major concerns related to the educational system. It was evident that women were not only concerned about the quality of education currently being received by their children but also the poor education they themselves received when growing up. Participants were especially concerned about the poor academic achievement of the children in their communities. For example, although there have been improvements over the years, the Hartford Public School district’s performance ranks substantially below that of most other school districts in the state.53 It is essential that there is more equitable financing of educational systems across the state and better educational resources available to parents.54

Perceived racial discrimination related to employment opportunities was identified by some participants. This is important since several studies have demonstrated that racism is a strong predictor of infant prematurity and low birthweight.13,16,18,52 Landale et al.55 investigated the relationship between maternal skin tone and low birthweight among Puerto Ricans living in three geographic areas (Puerto Rico; New York City; other eastern states). They found that in the other eastern states, mothers with dark skin have a higher risk of bearing a low birthweight infant, relative to mothers with light skin.

Finally, participants reported not having health insurance and how this prevented them from seeking medical services. By increasing access to health services, and appropriate perinatal care in minority populations, it is likely the rates of suboptimal pregnancy oucomes such as preterm labor, cesarean section, and gestational diabetes will improve.56

Similar findings from our focus groups with Puerto Rican women have been found through in-depth interviews with African American women.17,55,57

A possible limitation of this qualitative study was the fact that the convenience samples targeted are not representative of all Latina groups in the U.S. Nevertheless, because of the systematic analysis approach that was followed, the themes that were identified by participants provide the basis for future research with Latinas on the social determinants of stress/maternal health. Another limitation of the study was that some of the focus groups were conducted in Spanish and others in English. However, because we compared findings across focus groups and achieved informational saturation, the findings from this study are an accurate representation of the social stressors affecting Puerto Rican women of reproductive age with different language preferences. Since previous studies with Mexican women have documented significant differences in infant birthweight, head circumference, and percentile size by acculturation level (acculturation to mainland U.S.),58 it is indeed important for future research to address the role of acculturation on stress and birth outcomes among Puerto Rican women.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, policies to improve birth outcomes must target the socio-economic determinants of health. There is a clear need to conduct future research and to assess the causes (including perceived discrimination59) and impact of stress on the overall health of Puerto Rican women. Further research is also needed to develop valid stress and stress reactivity assessments to further our understanding of how the social determinants of health affect stress, and how stress affects health outcomes among Latinas of reproductive age.

Box 1.

FOCUS GROUP GUIDE QUESTIONS

| Stress | 1. In your own words what is stress? 2. How does stress affect people? Does stress play a role in a person’s health? How? 3. Many people experience stress in different ways. How do women in the community experience stress? 4. What makes people feel stressed? (Stressors) 5. What do people do to cope/deal with stress? What are some of the positive things? What are some of the negative things? |

| Income/Poverty | 1. How does income, or lack of income, create stress? 2. Do women in this community worry about not having enough money to meet their and/or their family’s basic needs? 3. Do women ever have to prioritize what they spend money on? How do they do this? Does this cause stress? 4. When women don’t have enough money for paying bills, are there any ways they can get support? 5. Do women have any way to improve their income? If so, how? |

| Food insecurity | 1. Do women in this community worry about not having enough food to feed themselves and their families? 2. Do women have the resources to purchase enough healthy food? 3. Does not having enough resources to purchase food cause stress? If so, how does this causes stress |

| Education | 1. Do women in this community ever worry about the school system? If so, what are their concerns? 2. Do you think that children in the school system will get the same opportunities as students in other towns? Please explain |

| Health Care Access and Treatment |

1. Do most people in this community have health insurance coverage? 2. Do women in this community ever worry about being able to pay to go see the doctor or for medicine that they or their families need? 3. Are people in this community ever discriminated against in the medical system? If so, how? |

| Physical environment/ Safety |

Do people in the community worry about their physical safety? If so, how do women and children adjust their lives because they worried about safety? Does this cause stress? |

| Working conditions |

1. Are there enough jobs in this community that pay enough to live? 2. What are the working conditions like for the people in this community? How these conditions contribute to stress? 3. Do people in the community experience discrimination at work? If so, based on what? 4. Are workers watched/targeted more closely at work because of race? How does this discrimination affect people? |

| Perceived discrimination/ Racism |

1. Do you know of examples where people in this community have been given treated with less dignity and respect because of their race? Please explain. 2. Do you feel that you were ever unfairly judged because of your race? If so, how? |

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the NIH EXPORT Center for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos, a consortium formed by the Hispanic Health Council, University of Connecticut, and Hartford Hospital. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health. This project was supported by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, NIH EXPORT Grant P20MD001765. Special thanks to the City of Hartford and Willimantic WIC Program, Windham Hospital, the Family Resource Centers in the city of Willimantic schools, public libraries, local convenience stores, grocery stores, Latino restaurants and the Hispanic Health Council Centers of Women and Children’s Health and Nutrition for granting permission to recruit participants at their sites or programs. We thank Gilma Galdamez and the staff from the Hispanic Health Council for their assistance implementing this study. We also thank Alison Stratton for her assistance with data analysis. Finally, deep appreciation to all of the women who opened their hearts to share their

NOTES

- 1.Braveman P, Marchi K, Egerter S, et al. Poverty, near-poverty, and hardship around the time of pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2010 Jan;14(1):20–35. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0427-0. Epub 2008 Nov 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lantz PM, House JS, Mero RP, et al. Stress, life events, and socioeconomic disparities in health: results from the Americans’ Changing Lives Study. J Health Soc Behav. 2005 Sep;46(3):274–88. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrie JE, Martikainen P, Shipley MJ, et al. Self-reported economic difficulties and coronary events in men: evidence from the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Jun;34(3):640–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi063. Epub 2005 Apr 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Calvo J, Jackson J, Hansford C, et al. Psychosocial factors and birth outcome: African American women in case management. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998 Nov;9(4):395–419. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn JR, Fazio EM. Economic status over the life course and racial disparities in health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005 Oct;60(Spec No 2):76–84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jan 15;338(3):171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steptoe A, Marmot M. The role of psychobiological pathways in socio-economic inequalities in cardiovascular disease risk. Euro Heart J. 2002 Jan;23(1):13–25. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teixeira JM, Fisk NM, Glover V. Association between maternal anxiety in pregnancy and increased uterine artery resistance index: cohort based study. BMJ. 1999 Jan 16;318(7177):153–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellhammer DH, Wüst S, Kudielka BM. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009 Feb;34(2):163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.026. Epub 2008 Dec 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nkansah-Amankra S, Luchok KJ, Hussey JR, et al. Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina, 2000–2003. Matern Child Health J. 2010 Mar;14(2):215–26. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0447-4. Epub 2009 Jan 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field T, Diego M. Cortisol: the culprit prenatal stress variable. Int J Neurosci. 2008 Aug;118(8):1181. doi: 10.1080/00207450701820944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miranda ML, Maxson P, Edwards S. Environmental contributions to disparities in pregnancy outcomes. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:67–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp011. Epub 2009 Oct 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dailey DE. Social stressors and strengths as predictors of infant birth weight in low-income African American women. Nurs Res. 2009 Sep-Oct;58(5):340–7. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181ac1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nkansah-Amankra S, Luchok KJ, Hussey JR, et al. Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina, 2000–2003. Matern Child Health J. 2010 Mar;14(2):215–26. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0447-4. Epub 2009 Jan 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schempf A, Strobino D, O’Campo P. Neighborhood effects on birthweight: an exploration of psychosocial and behavioral pathways in Baltimore, 1995–1996. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Jan;68(1):100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.006. Epub 2008 Nov 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Jan 1;157(1):14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuru-Jeter A, Dominquez TP, Hammond WP, et al. “It’s the skin you’re in”: African American women talk about their experiences of racism: an exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Matern Child Health J. 2009 Jan;13(1):29–39. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x. Epub 2008 May 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominguez TP, Dunkel-Schetter C, Glynn LM, et al. Racial differences in birth outcomes: the role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychol. 2008 Mar;27(2):194–203. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, et al. Prenatal depression restricts fetal growth. Early Hum Dev. 2009 Jan;85(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.07.002. Epub 2008 Aug 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, et al. Prenatal cortisol, prematurity and low birthweight. Infant Behav Dev. 2006 Apr;29(2):268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.12.010. Epub 2006 Feb 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, Zambrana RE. Health issues in the Latino community. Jossey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becerra JE, Hogue CJ, Atrash HK, et al. Infant mortality among Hispanics. A portrait of heterogeneity. JAMA. 1991 Jan 9;265(2):217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuentes-Afflick E, Hessol NA, Pérez-Stable EJ. Testing the epidemiologic paradox of low birth weight in Latinos. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999 Feb;153(2):147–53. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reichman NE, Kenney GM. Prenatal care, birth outcomes and newborn hospitalization costs: patterns among Hispanics in New Jersey. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998 Jul-Aug;30(4):182–7. 200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Infant health among Puerto Ricans—Puerto Rico and U.S. mainland, 1989–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003 Oct 24;52(42):1012–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkins FW, MacKay AP, Koonin LM, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in Hispanic women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Nov;94(5 Pt 1):747–52. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelaher M, Jessop DJ. Differences in low-birthweight among documented and undocumented foreign-born and U.S.-born Latinas. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Dec;55(12):2171–5. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Davila AL. The Puerto Rican maternal and infant health study. Penn State Population Research Institute; University Park, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.March of Dimes . Peristats: statistics using data from the National Center for Health Statistics. March of Dimes; White Plains, NY: 2011. Available at: www.marchofdimes.com/peristats. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorman BK. Developmental well-being among low and normal birth weight U.S. Puerto Rican children. J Health Soc Behav. 2002 Dec;43(4):419–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathews TJ, Menacker F, MacDorman MF, et al. Infant mortality statistics from the 2002 period: linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2004 Nov 24;53(10):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, et al. Deaths: final data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports. 19. Vol. 58. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: May 20, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization (WHO) Social determinants of health. WHO; Switzerland: 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Community Guide Branch . The guide to community preventive services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2010. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/social/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, et al. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008 Nov 8;372(9650):1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(Suppl):S15–27. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albert MA, Williams DR. Discrimination—an emerging target for reducing risk of cardiovascular disease? Am J Epidemiol. 2011 Jan 1;173(11):1240–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq514. Epub 2011 Feb 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bermúdez-Millán Angela. Egg contribution to nutrient intakes, pregnancy weight gain and birth outcomes among Connecticut Latinas. Dissertations for University of Connecticut. 2007 Available at: http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/AAI3265758.

- 39.Krueger RA. Analyzing and reporting focus group results (focus group kit) Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.IBM Corporation . SPSS software V19.0. IBM Corporation; Armonk, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Qualitative research guidelines project (web site) RWJF; Princeton, NJ: 2008. Available at: http://www.qualres.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kriska AM, Rexroad AR. The role of physical activity in minority populations. Womens Health Issues. 1998 Mar-Apr;8(2):98–103. doi: 10.1016/S1049-3867(97)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson SA, editor. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr. 1990 Nov;120(Suppl 11):1559–600. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Minority Consortia . Unnatural causes: is inequality making us sick. California Newsreel; San Francisco, CA: 2008. Available at: http://www.unnaturalcauses.org. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marrero DN. Suicide attempts among Puerto Ricans of low socioeconomic status. Sciences and Engineering. 1998 Jan;58(7-B):3929. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C, et al. Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. J Nutr. 2006 Jan;136(1):177–82. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hromi-Fiedler A, Bermudez-Millan A, Segura-Perez S, et al. Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms among low-income pregnant Latinas. Matern Child Nutr. 2010 Aug 23; doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Addo AA, Marquis GS, Lartey AA, et al. Food insecurity and perceived stress but not HIV infections are independently associated with lower energy intakes among lactating Ghanaian women. Matern Child Nutr. 2011 Jan;7(1):80–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins JW, Jr, David RJ, Symons R, et al. African American mothers’ perception of their residential environment, stressful life events, and very low birthweight. Epidemiology. 1998 May;9(3):286–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buka SL, Brennan RT, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Neighborhood support and the birth weight of urban infants. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Jan 1;157(1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holland ML, Kitzman H, Veazie P. The effects of stress on birth weight in low-income, unmarried Black women. Womens Health Issues. 2009 Nov-Dec;19(6):390–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collins JW, Jr, David RJ, Handler A, et al. Very low birthweight in African American infant: the role of maternal exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination. Am J Public Health. 2004 Dec;94(12):2132–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achieve Hartford . Achieve Hartford: a compact for education excellence (web site) Achieve Hartford; Hartford, CT: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ompad DC, Galea S, Caiaffa WT, et al. Social determinants of the health of urban populations: methodological considerations. J Urban Health. 2007 May;84(Suppl 1):42–53. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Landale NS, Oropesa RS. What does skin color have to do with infant health? An analysis of low birth weight among mainland and island Puerto Ricans. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Jul;61(2):379–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.029. Epub 2005 Apr 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen JJ, Tymkow C, MacMullen N. Disparities in maternal outcomes among four ethnic populations. Ethn Dis. 2005 Summer;15(3):492–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott AJ, Wilson RF. Social determinants of health among African Americans in a rural community in the Deep South: an ecological exploration. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1634. Epub 2011 Feb 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruiz RJ, Dolbier CL, Fleschler R. The relationships among acculturation, biobehavioral risk, stress, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and poor birth outcomes in Hispanic women. Ethn Dis. 2006 Autumn;16(4):926–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Todorova IL, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, et al. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociol Health Illn. 2010 Sep;32(6):843–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01257.x. Epub 2010 Jul 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]