Abstract

Objective

To explore the underlying physiology of hostility (HOST) and to test the hypothesis that HOST has a greater impact on fasting glucose in African American (AA) women than it does on AA men or white men or women, using an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) and the minimal model of glucose kinetics.

Methods

A total of 115 healthy subjects selected for high or low scores on the 27 item Cook Medley HOST Scale underwent an IVGTT. Fasting nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) levels were measured before the IVGTT. Catecholamine levels were measured 10 minutes into the IVGTT.

Results

Moderation by group (AA women versus others) of HOST was found for glucose effectiveness (Sg, p = .02), acute insulin response (AIRg, p = .02), and disposition index (DI, p = .02). AA women showed a negative association between HOST and both Sg (β = −0.45, p = .04) and DI (β = −0.49, p = .02), controlling for age and body mass index. HOST was also associated with changes in epinephrine (β = 0.39, p = .05) and fasting NEFA (β = 0.44, p = .02) in the AA women. Controlling for fasting NEFA reduced the effect of HOST on both Sg and DI.

Conclusions

This study shows that HOST is related to decreased DI, a measure of pancreatic compensation for increased insulin resistance as well as decreased Sg, a measure of noninsulin-mediated glucose transport compared in AA women. These effects are partly mediated by the relationship of HOST to fasting NEFA.

Keywords: hostility, African American, women, minimal model of glucose kinetics, nonesterified fatty acids, epinephrine

INTRODUCTION

It has been repeatedly reported that hostility (HOST) is related to perturbations in glucose metabolism in nondiabetic individuals (1–4). In a companion study by Georgiades et al. published in this issue, we report that a positive relationship between HOST and fasting glucose was observed only in African American (AA) women in a large sample of AA and white (W) men and women (5). This relationship was independent of body mass index (BMI). Although the mechanisms by which HOST could be associated with perturbations in glucose metabolism are not known, HOST has been associated with increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and adrenal cortical and medullary responding (6–8). Epinephrine (EPI) and cortisol are well-known counterregulatory hormones that can act to impair glucose metabolism via a variety of pathways. EPI can stimulate glycogenolysis and cortisol is able to stimulate endogenous glucose production through gluconeogenesis (9). EPI can also affect glucose metabolism through lypolysis (10) and the production of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) (11). NEFA have been implicated in the early pathology in glucose metabolism that precedes the development of Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (12, 13). Elevations in NEFA have been shown to reduce insulin sensitivity in both muscle and liver as well as glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the β cell (14). Bergman (15) has developed a mathematical model of glucose metabolism, the minimal model, from which assessments of pancreatic function as well as both insulin and noninsulin-mediated glucose transport can be estimated from an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT). He has hypothesized that the proximal cause of elevations in fasting glucose are increased levels of NEFA secondary to elevated sympathoadrenal function. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that HOST has a greater effect on glucose kinetics during an IVGTT in AA women as compared with AA men andWmen and women. We also expected that the effects of HOST on parameters of glucose metabolism would be associated with HOST-related differences in NEFA and catecholamines.

METHODS

Participants

This study was conducted between January 2004 and April 2007, and includes 115 healthy AA or W volunteers between the ages of 25 to 45 years, with BMI between 20 and 45 kg/m2. Ethnicity was based on self-report. Participants were recruited from a pool of 400 subjects, who had earlier completed an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and a battery of HOST and anger questionnaires, which included a 27-item version of the Cook Medley HOST Scale. The Cook Medley HOST Scale is composed by three subscales with items assessing cynicism, hostile affect, and aggressiveness, and has been found to be a better predictor of health outcome than the original 50-item scale (16). Tertile cutoffs from Cook Medley HOST Scale distributions assessed in a large-scale epidemiological study were used to select subjects (17). Subjects with Cook Medley HOST Scale scores of <9 were included as low-hostile and individuals with scores of >12 as high-hostile. Roughly equal numbers of high-hostile AA men (n = 16) and low-hostile AA men (n = 13), high-hostile AA women (n = 15), low-hostile AA women (n = 14), high-hostile W men (n = 15), low-hostile W men (n = 15), high-hostile W women (n = 13), and low-hostile W women (n = 14) were enrolled. Participants were screened for a fasting glucose of <120 mg/dl and a 2-hour postchallenge glucose of <140 mg/dl derived from the OGTT. Exclusion criteria for participation included abnormal glucose tolerance, history of epilepsy, adrenal insufficiency or other neuroendocrine dysfunction, pregnancy or breast feeding, and blood count and serum chemistries outside acceptable limits. The study was approved by the Duke University Health Systems Institutional Review Board, and all subjects gave their written informed consent to participate.

Procedures

Subjects fasted overnight, and were admitted to the Duke General Clinical Research Unit between 8 and 9 AM. Weight and height were measured to establish BMI and determine the glucose dose for the IVGTT. Two indwelling catheters were inserted, one on the right arm for the blood draw and one on the left arm for injection of the glucose bolus. Subjects rested for 30 minutes before the start of the IVGTT study and remained recumbent for the whole study period. Samples were collected for fasting glucose, insulin, and NEFA plasma concentrations as well as salivary cortisol concentration before administration of the glucose bolus. A frequently sampled IVGTT was employed (without insulin injection). A 302-mg/kg body weight bolus of glucose (maximum 35 g) was injected intravenously over a minute at time −1 minute through the left arm line. Blood samples were then obtained from the other intravenous line at times 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 18, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120, 140, 150, 160, 180, 210, and 240 minutes. Each sample was immediately centrifuged at 4°C, and plasma was separated and stored at −20°C until the assays were conducted.

Plasma glucose was determined by a hexokinase method and plasma insulin was determined by standard radioimmunoassay method (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts).

NEFA levels were determined in the pre-IVGTT fasting sample, using the Wako HR Series NEFA-HR (ACS ACOD method, Wako Chemicals, Richmond, Virginia), an in vitro enzymatic colorimetric method assay for the quantitative determination of NEFA in serum (18).

Plasma catecholamines were measured in samples collected before the glucose bolus was administered and at 5 and 10 minutes of the IVGTT. These samples were collected into tubes containing heparin and glutathione, and centrifuged in the cold. Plasma samples were then stored frozen at −80° until analysis.

Analysis of plasma levels of EPI and norepinephrine (NOREPI) were conducted by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (19). Change scores for EPI and NOREPI levels (difference between baseline and the mean of the 5- and 10-minute levels) were calculated to establish a response estimate (Δ) for these counterregulatory hormones.

Fasting salivary cortisol was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a kit from Oxford Biomedical Research (Oxford, Michigan) (20) at the General Clinical Research Center on the morning of the IVGTT.

The glucose and insulin samples were analyzed using the minimal model of glucose kinetics (21). The standard variables derived from the minimal model were a) insulin sensitivity (Si), a measure of the capability of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake; b) glucose effectiveness (Sg), a measure of glucose-facilitated, insulin-independent glucose uptake; c) acute insulin response (AIRg), representing the area under the curve for circulating insulin above basal level for the first 10 minutes post glucose injection; and d) disposition index (DI), the arithmetic product of insulin sensitivity and acute insulin response (Si × AIRg).

Physical activity was measured after the IVGTT through self-report with the short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The IPAQ is an instrument developed for surveillance of physical activity in adults and has shown to have sound measuring properties for monitoring population levels of physical activity among 18- to 65-year-olds in diverse settings (22). The IPAQ assesses the total amount of walking each week as well as the frequency and duration of moderate and vigorous exercises both at work and during leisure activities. Each activity is then weighted by its energy requirements defined as metabolic equivalents (METs), and further computation yields a final score of MET-minutes/week.

Statistical Analysis

Variables to be used in the linear models were examined for skewness. A natural logarithmic transformation (ln) was computed for Si, AIRg, and DI to reduce the positive skew of the distributions of these variables. Because it was hypothesized that HOST would be associated with the minimal model outcomes specifically in the AA women, the three other groups were combined in the tests of moderation of the relationship between HOST and minimal model variables. This led to the formulation of regression models that contained two factors, group (AA women versus others) and HOST. Stratified linear regression analysis was also conducted to explore associations of HOST to minimal model variables as well as to examine the role of counterregulatory hormones and NEFA in the HOST to minimal model associations. Because age and BMI have been associated to HOST (17, 23) and BMI has been related to the glucose metabolism (24, 25), the stratified regression analysis of the HOST to minimal model associations as well as the HOST to NEFA associations are presented both unadjusted and adjusted for BMI and age as they are potential confounders. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SPSS (version 15.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Subject characteristics are summarized by race and sex in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Study Characteristics by Race and Sex (Mean ± Standard Deviation)

| African American |

White |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| n | 29 | 29 | 27 | 30 |

| Cook Medley HOST | 11.3 ± 7.7 | 12.8 ± 6.8 | 9.4 ± 7.0 | 10.8 ± 5.9 |

| Age (years) | 34.7 ± 5.2 | 33.8 ± 6.6 | 33.8 ± 7.2 | 33.8 ± 5.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.7 ± 6.5 | 29.3 ± 5.0 | 25.2 ± 4.5 | 26.9 ± 4.1 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 87.2 ± 5.8 | 93.9 ± 8.7 | 83.6 ± 6.5 | 92.5 ± 7.3 |

| Fasting insulin (µU/ml) | 13.5 ± 8.3 | 13.0 ± 8.2 | 10.7 ± 4.7 | 10.7 ± 6.4 |

| EPI baseline (pg/ml) | 36.4 ± 5.6 | 50.1 ± 5.6 | 22.7 ± 5.8 | 42.9 ± 5.5 |

| EPI during IVGTT (pg/ml) | 33.0 ± 22.4 | 43.7 ± 24.7 | 22.6 ± 11.7 | 34.4 ± 26.6 |

| NOREPI baseline (pg/ml) | 255 ± 115 | 264 ± 103 | 286 ± 151 | 246 ± 109 |

| NOREPI during IVGTT (pg/ml) | 320.7 ± 135.0 | 274.3 ± 110.8 | 316.2 ± 201.7 | 258.7 ± 101.7 |

| Cortisol (ng/ml) | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 4.3 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 2.0 |

| NEFA (mEq/l) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Sg (100 min−1) | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Si (10−4 min−1/µU/ml) | 4.4 ± 4.9 | 5.1 ± 5.0 | 5.8 ± 4.8 | 5.6 ± 3.5 |

| AIRg (µU/ml × min) | 951.3 ± 750.5 | 1211.2 ± 861.7 | 577.9 ± 273.7 | 512.2 ± 379.2 |

| DI | 2717.9 ± 2168.0 | 5048.1 ± 5050.0 | 2683.0 ± 1497.1 | 2120.0 ± 1124.1 |

| PA (MET min/week/100) | 33.0 ± 14.2 | 102 ± 85.7 | 30.0 ± 23.4 | 42.0 ± 37.3 |

HOST = hostility; BMI = body mass index; EPI = epinephrine; IVGTT = intravenous glucose tolerance test; NOREPI = norepinephrine; NEFA = nonesterified fatty acids; Sg = glucose effectiveness; Si = insulin sensitivity; AIRg = acute insulin response; DI = disposition index; PA = physical activity; MET = metabolic equivalent.

HOST and Minimal Model

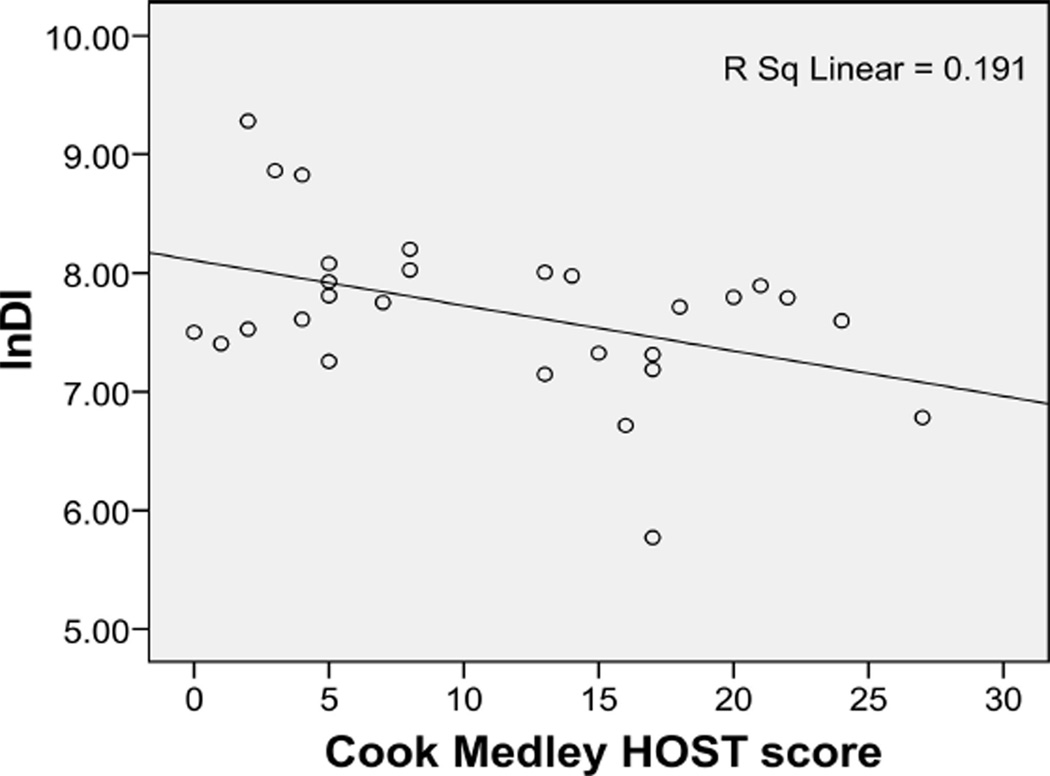

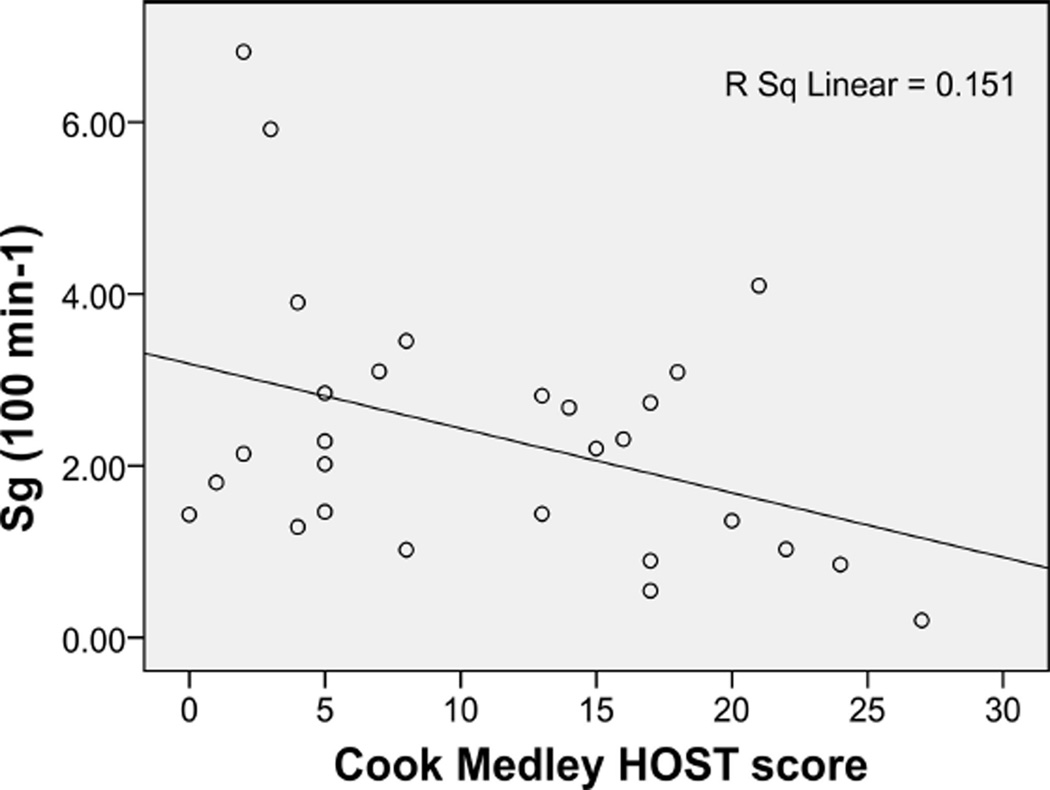

Subject group moderated the relationship between HOST and Sg (p = .04), lnAIRg (p = .02), and lnDI (p = .02). Stratified regression analysis revealed negative relationships in AA women between HOST and Sg and lnDI (Figures 1 and 2), relationships that remained significant after adjustment for age and BMI (Table 2). There were no significant associations between HOST and the Sg or lnDI in the comparison group (Table 2). Exploration of the moderation of the relationship between HOST and lnAIRg revealed a trend toward a negative relationship in AA women and a trend toward a positive relationship in the comparison group, when controlling for age and BMI (see Table 2). Analysis of lnSi revealed no moderation by group (p = .18) and no main effect of HOST (p = .57). There was no significant association between HOST and lnSi in neither the AA women nor the comparison group (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Relationship between Cook Medley hostility (HOST) scores and natural logarithmic transformation disposition index (lnDI) levels in African American women.

Figure 2.

Relationship between Cook Medley hostility (HOST) scores and glucose effectiveness (Sg) levels in African American women.

TABLE 2.

Regression Coefficients for the Association Between Cook Medley HOST Scores and the Minimal Model Outcome Variables

| African American Women (n = 29) |

Others (n = 86) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | |

| Sg | ||||

| Unadjusted | −0.39 | .04 | 0.10 | .38 |

| Adjusted for age and BMI | −0.45 | .05 | 0.15 | .19 |

| lnDI | ||||

| Unadjusted | −0.44 | .02 | 0.14 | .20 |

| Adjusted for age and BMI | −0.49 | .02 | 0.13 | .23 |

| lnAIRg | ||||

| Unadjusted | −0.25 | .19 | 0.21 | .05 |

| Adjusted for age and BMI | −0.37 | .09 | 0.19 | .08 |

| lnSi | ||||

| Unadjusted | −0.13 | .52 | −0.03 | .82 |

| Adjusted for age and BMI | −0.08 | .71 | −0.01 | .90 |

HOST = hostility; BMI = body mass index; ln = natural logarithmic transformation; Sg = glucose effectiveness; Si = insulin sensitivity; AIRg = acute insulin response; DI = disposition index.

HOST in Association to Fasting NEFA, Counterregulatory Hormones, Physical Activity, and BMI

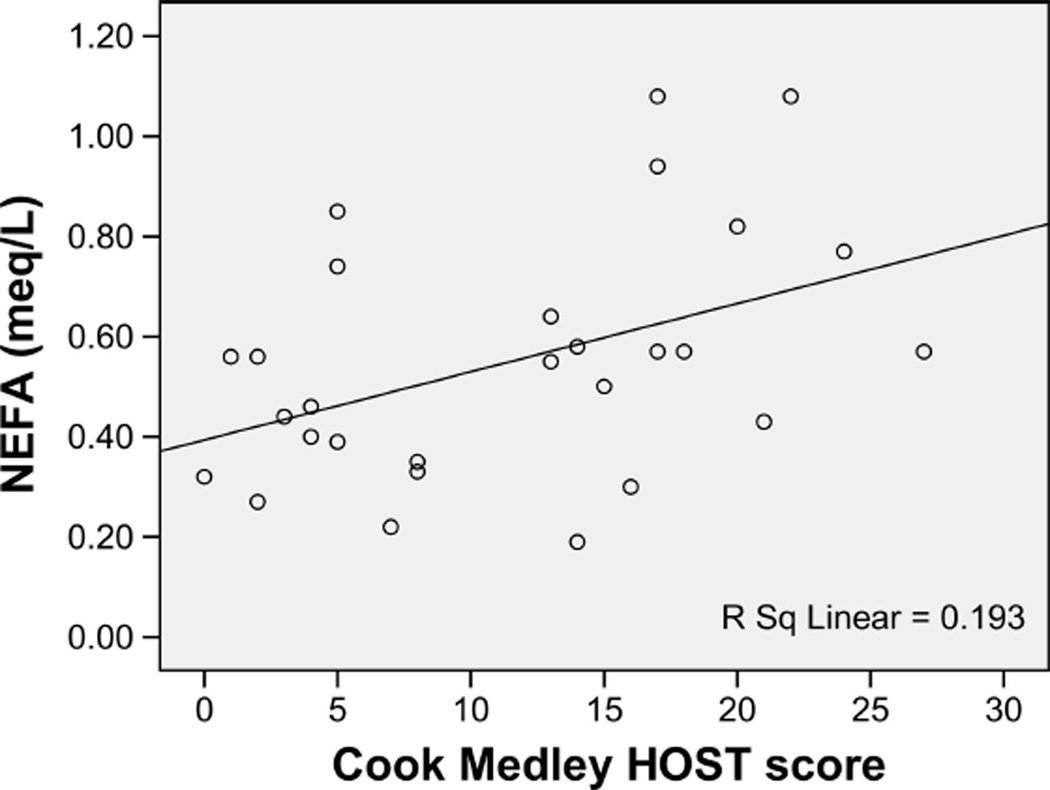

There was a significant HOST × group interaction on NEFA (p = .001), with stratified analysis revealing that AA women showed a significant positive association between HOST and fasting NEFA (β = 0.44, p = .02) (Figure 3), whereas there was a trend toward a negative association in the comparison group (β = −0.19, p = .08). The effect of HOST on NEFA in the AA women was still evident after controlling for age and BMI (β = 0.38, p = .05).

Figure 3.

Relationship between Cook Medley hostility (HOST) scores and fasting nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) in African American women.

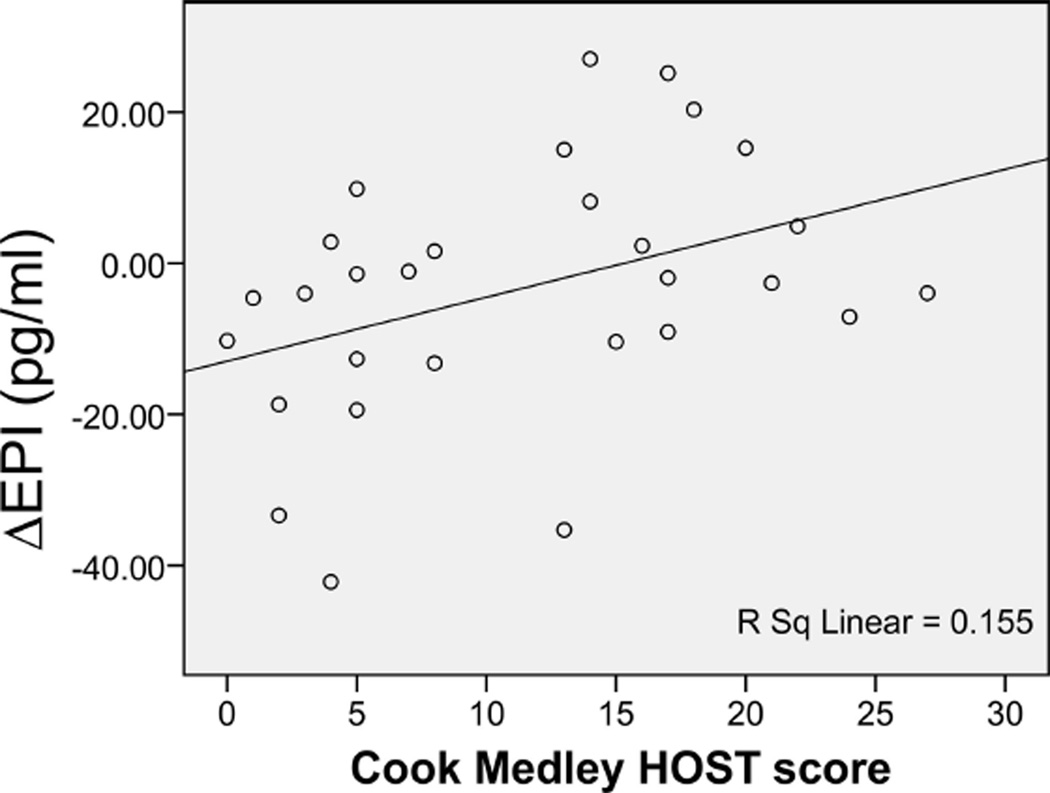

There was also a significant HOST by group interaction on ΔEPI (p = .02), with HOST being significantly related to ΔEPI levels in the AA women (β = 0.39, p = .05) (Figure 4), whereas there was no association between HOST and ΔEPI in the comparison group (β = −0.13, p = .25). There was a significant HOST by group interaction on baseline NOREPI levels (p = .02) with baseline NOREPI being negatively associated to HOST in the comparison group (β = −0.41, p = .001), but not associated to HOST in the AA women (β = 0.02, p = .095) There were no significant HOST by group interactions on baseline EPI, or fasting salivary cortisol levels nor was there a HOST by group interaction on ΔNOREPI levels (all p = .20).

Figure 4.

Relationship between Cook Medley hostility (HOST) scores and epinephrine (EPI) change in African American women.

There was a trend toward a HOST × group interaction on level of self-reported physical activity (p = .07), whereas the main effect of HOST to physical activity was significant (β = 0.21, p = .02).

Finally, there was a trend toward a HOST × group interaction to BMI (p = .08), whereas the main effect of HOST to BMI was significant (β = 0.21, p = .02).

Examining the Role of Fasting NEFA, ΔEPI and Physical Activity in the HOST to Minimal Model Associations in AA Women

Fasting NEFA was associated to both lnDI (β = −0.45, p = .02) and Sg (β = −0.39, p = .04) in the AA women. In addition, fasting NEFA levels were significantly related to lnSi in the AA women (β = −0.43, p = .02), but there was no association of NEFA to AIRg (p = .43).

When controlling for NEFA, analysis showed that the association between HOST and lnDI was reduced to nonsignificance (adjusted β = −0.25, p = .23). The same pattern was evident for the HOST and Sg relationship, where the association was reduced when NEFA was controlled for (adjusted β = −0.27, p = .21), suggesting that the HOST to Sg and DI associations are partly mediated by NEFA among AA women.

Simple regression analysis showed that ΔEPI was not related to lnDI (p = .18) or Sg (p = .50) in the AA women. Adjusting for ΔEPI did not affect the HOST to lnDI association (β = −0.40, p = .05) or the HOST to Sg association (β = −0.45, p = .04) in the AA women.

Finally, there was no association between physical activity calculated as MET-minutes/week and HOST (β = −0.03, p = .87), NEFA (β = −0.02, p = .92), DI (β = −0.07, p = .70), Sg (β= −0.08, p = .65) in the AA women.

DISCUSSION

As a group, AA women are at particular risk for obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular and renal disease in comparison to their W counterparts (26–30), but it is not clear to what extent these differences are due to gene frequencies, epigenetic or psychosocial factors. Our present study extends our findings that HOST is related to fasting glucose in AA females by showing that HOST affects several specific parameters of the minimal model of glucose kinetics in this population. Specifically, higher scores of HOST were associated with lower levels of DI and Sg in AA women. DI represents the ability of β cells in the pancreas to compensate for insulin resistance by releasing more insulin. Individuals who have impaired glucose tolerance show lower DI scores, which reflects a relative failure of the pancreas in the face of increased insulin resistance. DI is a heritable trait (31), and has been shown to be genetically determined in AAs (32). Given that low DI has been shown to be one of the earliest predictors of conversion from normal glucose tolerance to T2DM (33), the observed negative relationship of HOST to DI in AA women suggests that HOST may be a critical factor associated with impaired glucose homeostasis in this population. Thus, our data add to a growing literature that suggests AA women have specific vulnerabilities compared with AA men or Ws of either gender. The clinical significance of the relationship of HOST to Sg is less obvious. Sg is a measure of glucose’s ability to stimulate its own uptake, independent of insulin. Whereas impaired Sg can contribute to hyperglycemia, its role in the etiology of T2DM is not as well understood. Although Sg has been shown to be related to physical fitness as measured by maximum oxygen consumption (34, 35), our data did not show an association between self-report of physical activity and hostility, NEFA, or Sg in the AA women.

HOST was significantly related to BMI in our sample of AA females. This association of HOST to BMI has been noted before (36), and has been attributed to excess caloric intake in high HOST individuals (37). BMI itself is a well-established risk factor for abnormal glucose metabolism (24, 25). However, controlling for BMI did not affect the relationship of HOST to any of the minimal model variables in the AA females. Interestingly, HOST was also positively related to fasting NEFA in AA females, even after controlling for BMI and age. It is now widely believed that abnormalities in glucose metabolism are driven, in part, by increased NEFA that compete with glucose during oxidative phosphorylation (13, 38, 39). Increased NEFA would be expected to reduce both insulin-mediated and noninsulin-mediated glucose transport. NEFA has also been hypothesized to impair β-cell response to glucose, which would account for the observed relationship of NEFA and both DI and Sg. Controlling for fasting NEFA reduced the association of HOST to DI and of HOST to Sg. Thus, NEFA may play a mediating role in the association of HOST to DI and Sg.

HOST may also be related to Sg through a third variable, such as physical fitness. Studies have shown Sg to be related to level of physical fitness (34, 35) and that exercise training can improve Sg (40). Because HOST may be related to reduced levels of physical activity in AA women, this is one other mechanism by which HOST and Sg could be related. However, results from our study using the IPAQ survey did not find any relationship between HOST and physical activity in AA women.

Sympathoadrenal reactivity has been shown to be higher in high HOST than in low HOST individuals (6–8). We observed that HOST was related to increases in EPI during the first 10 minutes of the IVGTT in the AA women. Catecholamines can raise energy mobilizations by increasing glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, as well as lypolysis. Therefore, increases in EPI levels during the IVGTT could have accounted for the relationship of HOST to DI and Sg in the high HOST AA women. This increase in plasma EPI during the first 10 minutes could not be attributed to the osmotic effect of the glucose challenge as there was no general increase in EPI in the first 10 minutes in the entire sample. Furthermore, EPI and NOREPI changed in opposite directions in most subjects. However, controlling for the EPI response (ΔEPI) did not affect the relationship of HOST to either DI or Sg in the AA women. The model proposed by Bergman (15) hypothesized that elevated nocturnal sympathoadrenal activity negatively affects glucose metabolism by stimulating fasting NEFA release from visceral adipose tissue. Because we did not measure nocturnal catecholamines before the time fasting NEFA was collected, this hypothesis could not be tested. However, in a recent pilot study (41), we found that the relationship between HOST and fasting glucose was specifically mediated by trunk fat as assessed by dual X-ray densitometry rather than BMI. The role of nocturnal SNS activity in the relationship of HOST to perturbations of glucose kinetics in AA females remains unanswered.

HOST has been related to depression and socioeconomic status, both of which have been shown to affect health outcomes (42). Thus, interpretation of our findings must take into consideration that there may be some overlap between HOST and other psychosocial characteristics related to health. Other groups have shown that much of the variance in HOST is unique to this construct (43, 44), and that HOST has been shown to predict incident hypertension (44) and C-reactive protein (45) independently of depressive symptoms.

In conclusion, our results suggest that HOST influences multiple parameters of glucose kinetics in AA women. High HOST AA women show both decreased noninsulin-mediated glucose transport as well as decreased pancreatic function. Although the mechanism through which HOST affects these parameters is not immediately apparent, the positive relationship between HOST and NEFA may play a crucial role. We hypothesize that the relationship of HOST to NEFA is mediated by counterregulatory hormones and central adiposity, and that NEFA drives the effects of HOST to the minimal model changes. Understanding how HOST can affect diabetes and cardiovascular disease and indentifying targets for new pharmacologic and/or behavioral interventions for preventing the development of these diseases is an important target, especially in this high-risk group. Future studies employing frequent measures of NEFA and EPI before as well as throughout the IVGTT will be needed to better understand the role of EPI and NEFA in the relationship of HOST to abnormalities in glucose metabolism in AA women.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Grant HL-076020 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and Grant 913 from the GCRC. This study was also supported by Grant HL-036587 to 19 from the Program Project and the Behavioral Medicine Research Center at Duke University School of Medicine.

Glossary

- AA

African American

- BMI

body mass index

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DI

disposition index

- EPI

epinephrine

- HOST

hostility

- IVGTT

intravenous glucose tolerance test

- IPAQ

international physical activity questionnaire

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acids

- NOREPI

norepinephrine

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- Sg

glucose effectiveness

- Si

insulin sensitivity

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- W

white

REFERENCES

- 1.Niaura R, Banks SM, Ward KD, Stoney CM, Spiro A, 3rd, Aldwin CM, Landsberg L, Weiss ST. Hostility and the metabolic syndrome in older males: The normative aging study. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:7–16. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raikkonen K, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Hautanen A. The role of psychological coronary risk factors in insulin and glucose metabolism. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:705–713. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitaliano PP, Scanlan JM, Krenz C, Fujimoto W. Insulin and glucose: relationships with hassles, anger, and hostility in nondiabetic older adults. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:489–499. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surwit RS, Williams RB, Siegler IC, Lane JD, Helms M, Applegate KL, Zucker N, Feinglos MN, McCaskill CM, Barefoot JC. Hostility, race, and glucose metabolism in nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:835–839. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Georgiades A, Lane JD, Boyle SH, Brummett BH, Barefoot JC, Kuhn CM, Feinglos MN, Williams RB, Merwin R, Minda S, Siegler IC, Surwit RS. Hositility and fasting glucose in African American women. Psychosom Med. 2009;70:642–645. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181acee3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope MK, Smith TW. Cortisol excretion in high and low cynically hostile men. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:386–392. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Niaura R, Dyer JR, Shen BJ, Todaro JF, McCaffery JM, Spiro A, 3rd, Ward KD. Hostility and urine norepinephrine interact to predict insulin resistance: The VA normative aging study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:718–726. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000228343.89466.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Williams RB, Jr, Zimmermann EA. Neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and emotional responses of hostile men: The role of interpersonal challenge. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:78–88. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerich J, Cryer P, Rizza R. Hormonal mechanisms in acute glucose counterregulation: The relative roles of glucagon, epinephrine, norepinephrine, growth hormone, and cortisol. Metabolism. 1980;29:1164–1175. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray GA. Effects of epinephrine, corticotropin, and thyrotropin on lipolysis and glucose oxidation in rat adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 1967;8:300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orth RD, Williams RH. Response of plasma NEFA levels to epinephrine infusions in normal and obese women. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960;104:119–120. doi: 10.3181/00379727-104-25748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pankow JS, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Ballantyne CM, Couper DJ, Hoogeveen RC, Golden SH. Fasting plasma free fatty acids and risk of type 2 diabetes: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:77–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilding JP. The importance of free fatty acids in the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2007;24:934–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duez H, Lewis GF. Fat metabolism in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. In: Feinglos MN, Bethel MA, editors. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Evidence-Based Approach to Practical Management. Vol 1. Durham, NC: Humana Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergman RN. Orchestration of glucose homeostasis: From a small acorn to the California oak. Diabetes. 2007;56:1489–1501. doi: 10.2337/db07-9903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB., Jr The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosom Med. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barefoot JC, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Siegler IC, Anderson NB, Williams RB., Jr Hostility patterns and health implications: Correlates of Cook-Medley hostility scale scores in a national survey. Health Psychol. 1991;10:18–24. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miksa IR, Buckley CL, Poppenga RH. Detection of nonesterified (free) fatty acids in bovine serum: Comparative evaluation of two methods. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004;16:139–144. doi: 10.1177/104063870401600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilts CD, Gooch MD, Knopes KD. Quantitation of plasma catecholamines by on-line trace enrichment high performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11:257–273. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. Salivary cortisol in psychoneuroendocrine research: Recent developments and applications. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1994;19:313–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boston RC, Stefanovski D, Moate PJ, Sumner AE, Watanabe RM, Bergman RN. MINMOD millennium: a computer program to calculate glucose effectiveness and insulin sensitivity from the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2003;5:1003–1015. doi: 10.1089/152091503322641060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegler IC, Costa PT, Brummett BH, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC, Williams RB, Dahlstrom WG, Kaplan BH, Vitaliano PP, Nichaman MZ, Day RS, Rimer BK. Patterns of change in hostility from college to midlife in the UNC alumni heart study predict high-risk status. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:738–745. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088583.25140.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu G, Lindstrom J, Valle TT, Eriksson JG, Jousilahti P, Silventoinen K, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J. Physical activity, body mass index, and risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with normal or impaired glucose regulation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:892–896. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Sullivan L, Fox CS, Nathan DM, D’Agostino RB., Sr Prediction of incident diabetes mellitus in middle-aged adults: The Framingham offspring study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1068–1074. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson SO, Haiman CA, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Wan P, Pike MC. Established risk factors account for most of the racial differences in cardiovascular disease mortality. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS, Goldstein DE, Little RR, Wiedmeyer HM, Byrd-Holt DD. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:518–524. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris MI, Eastman RC, Cowie CC, Flegal KM, Eberhardt MS. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:403–408. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanjilal S, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Zhang P, Nelson DE, Mensah G, Beckles GL. Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971–2002. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2348–2355. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulsen P, Levin K, Petersen I, Christensen K, Beck-Nielsen H, Vaag A. Heritability of insulin secretion, peripheral and hepatic insulin action, and intracellular glucose partitioning in young and old Danish twins. Diabetes. 2005;54:275–283. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rich SS, Bowden DW, Haffner SM, Norris JM, Saad MF, Mitchell BD, Rotter JI, Langefeld CD, Wagenknecht LE, Bergman RN. Identification of quantitative trait loci for glucose homeostasis: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study (IRAS) family study. Diabetes. 2004;53:1866–1875. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weyer C, Hanson K, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Long-term changes in insulin action and insulin secretion associated with gain, loss, regain and maintenance of body weight. Diabetologia. 2000;43:36–46. doi: 10.1007/s001250050005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tokuyama K, Suzuki M. Intravenous glucose tolerance test-derived glucose effectiveness in endurance-trained rats. Metabolism. 1998;47:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishida Y, Tokuyama K, Nagasaka S, Higaki Y, Fujimi K, Kiyonaga A, Shindo M, Kusaka I, Nakamura T, Ishikawa SE, Saito T, Nakamura O, Sato Y, Tanaka H. S(G), S(I), and EGP of exercise-trained middle-aged men estimated by a two-compartment labeled minimal model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E809–E816. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00237.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunde J, Suls J. A quantitative analysis of the relationship between the Cook-Medley hostility scale and traditional coronary artery disease risk factors. Health Psychol. 2006;25:493–500. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherwitz LW, Perkins LL, Chesney MA, Hughes GH, Sidney S, Manolio TA. Hostility and health behaviors in young adults: The CARDIA study. Coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:136–145. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy A, Parker RS. Dynamic modeling of free fatty acid, glucose, and insulin: an extended"minimal model". Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8:617–626. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.8.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roden M. How free fatty acids inhibit glucose utilization in human skeletal muscle. News Physiol Sci. 2004;19:92–96. doi: 10.1152/nips.01459.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishida Y, Tokuyama K, Nagasaka S, Higaki Y, Shirai Y, Kiyonaga A, Shindo M, Kusaka I, Nakamura T, Ishibashi S, Tanaka H. Effect of moderate exercise training on peripheral glucose effectiveness, insulin sensitivity, and endogenous glucose production in healthy humans estimated by a two-compartment-labeled minimal model. Diabetes. 2004;53:315–320. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Georgiades A, Surwit RS, Williams RB. Hostility and glucose indices in African American and Caucasian females: The mediating role of trunk fat. Pychosom Med. 2008;70:A-69. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith TW, Glazer K, Ruiz JM, Gallo LC. Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: an interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health. J Pers. 2004;72:1217–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sykes DH, Arveiler D, Salters CP, Ferrieres J, McCrum E, Amouyel P, Bingham A, Montaye M, Ruidavets JB, Haas B, Ducimetiere P, Evans AE. Psychosocial risk factors for heart disease in France and Northern Ireland: The prospective epidemiological study of myocardial infarction (PRIME) Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1227–1234. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan LL, Liu K, Matthews KA, Daviglus ML, Ferguson TF, Kiefe CI. Psychosocial factors and risk of hypertension: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA. 2003;290:2138–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham JE, Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB, Bissell MG, Glaser R. Hostility and pain are related to inflammation in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]