Abstract

Previous research has demonstrated that the offspring of depressed mothers are at greater risk for negative psychopathological and psychosocial outcomes than children of non-depressed mothers. The current study specifically examines offspring’s romantic relationship quality during the transition to adulthood as a function of maternal depression and three putative mechanisms for this association: youth depression history, mother-child relationship discord, and maternal romantic relationship difficulties. The study further explores the role of these factors in the risk for depressive symptoms during the transition to adulthood. Hypotheses were examined longitudinally in a community sample of 182 Australian youth who were followed from birth to age 20 and were in committed romantic relationships at age 20 with romantic partners willing to provide data regarding romantic relationship satisfaction. Structural equation modeling analyses found support for a direct effect of maternal depression on youth romantic relationship quality with significant mediation by mother-child relationship discord, as well as an association between mother-child relationship discord and later depressive symptoms that is mediated by youth romantic relationship quality. Findings also lend support for an indirect effect from maternal depression to youth depressive symptoms via mother-child relationship discord and youth romantic relationship quality. This study provides further evidence for the negative psychosocial and psychopathological outcomes of children of depressed mothers and the intergenerational transmission of relational difficulties.

Keywords: maternal depression, youth romantic relationships, mother-child interactions, romantic partner reports

An interpersonal perspective on depression emphasizes the social vulnerabilities and risk factors, interpersonal stress precipitants, and social consequences of depression. The interpersonal focus on depression in adolescence is supported by ample evidence of social dysfunction and maladaptive interpersonal cognitions such as expectations and beliefs (e.g., excessive reassurance-seeking, insecure attachment cognitions), problematic family relationships that impair skills (e.g., marital and parenting problems predicting lower social competence and peers difficulties), and social stressors (interpersonal life events) that predict increases in depressive symptoms or onsets of depressive episodes (e.g., Carter & Garber, 2011; Eberhart & Hammen, 2010; Hammen, Shih, & Brennan, 2004; Joiner & Timmons, 2009).

Interpersonal processes also play an important role in the intergenerational transmission of depression. Along with the well-established link between parental depression and offspring disorders (reviewed in Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall, & Heyward, 2011), there is emerging evidence of dysfunctional social outcomes in the children of depressed parents. Longitudinal studies indicate that these youth have poorer adjustment in social roles, lower perceived support, and more interpersonal stress associated with having depressed parents (e.g., Adrian & Hammen, 1993; Lewinsohn, Olino, & Klein, 2005; Shih, Abela, & Starrs, 2009; Weissman et al., 2006). Thus, children of depressed parents are at risk, not only for depression and other psychopathology, but also for maladaptive interpersonal cognitions, behaviors, and social outcomes that may contribute to their vulnerability to depression.

In their recent meta-analysis, Goodman et al. (2011) call for moving beyond main effects models of the role of maternal depression, and toward developing models that are specific to particular aspects of children’s functioning. We propose that one pathway of the future perpetuation of dysfunction (and depression) across generations is romantic relationship maladjustment, the continuing creation of or selection into difficult close relationships. This framework is consistent with an interpersonal focus on depression noted above, and with the stress generation perspective (Hammen, 1991) in which individuals with histories of depression have been shown to experience higher rates of stressful life events to which they have contributed (largely interpersonal in content), compared to those without depression. Research in longitudinal studies with adults, adolescents, and children, and with clinical and community samples, has shown that individuals with previous depression, compared to the nondepressed, have more negative life events, especially those dependent on behaviors and characteristics of the person (Hammen & Shih, 2008). Extending stress generation to include chronic stressful circumstances (e.g., Hammen, Brennan, & LeBrocque, 2011), we hypothesize that depressed youth contribute to ongoing negative situations, such as poor quality relationships, that perpetuate the experiences of stress and depression. The current longitudinal study proposes a model in which maternal depression portends risk for poor romantic relationship quality and depression among youth through multiple mechanisms. We proposed the following hypotheses regarding the intergenerational transmission of relationship difficulties and depression.

Maternal depression predicts youth romantic relationship quality at age 20 by way of three potential mediating factors.

Maternal depression predicts youth depression (e.g., Goodman et al., 2011; Hammen, 2009), and youth depression is a predictor of romantic relationship difficulties, as often noted among depressed adults (e.g., Whisman, Uebelacker, & Weinstock, 2004). Vujeva and Furman (2011) found that youth depression at 15 predicted increases in romantic relationship conflict over time and less gain in positive relationship problem-solving. Youth depression has been found to be associated with romantic partners’ reports of relationship dissatisfaction and poor conflict resolution (Rao, Hammen, & Daley, 1999). Gotlib, Lewinsohn, and Seeley (1998) found that depression in adolescence predicted higher rates of marital distress in early adulthood.

-

Two additional proposed mediators of the association between maternal depression and youth romantic relationship dysfunction are poor quality of the maternal marital relationship and dysfunction in the mother’s relationship with the child. Depression has been shown to be associated with marital distress and poor conflict resolution (e.g., Coyne, Thompson & Palmer, 2002; Davila, Karney, Hall, & Bradbury, 2003; Whisman, Uebelacker, & Weinstock, 2004), suggesting that depressed mothers may be at greater risk for marital difficulties.

Depression is also associated with parenting difficulties, including negative/hostile interactions, lower rates of positive behaviors, and disengagement (ignoring, withdrawal, gaze aversion) (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Several studies suggest that marital and parenting difficulties mediate the effects of maternal depression on youth diagnostic and symptom outcomes (e.g., Hammen, Shih, & Brennan, 2004; Leinonen, Solantaus, & Punamaki, 2003). Further, studies of the intergenerational transmission of relationship problems provide substantial evidence that both poor quality parent-child relationships and marital discord predict difficulties (conflict, poor quality, breakups) in intimate relationships in older adolescents and young adults (e.g., Amato & Booth, 2001; Cui, Durtschi, Donnellan, Lorenz, & Conger, 2010; Hare, Miga, & Allen, 2009).

-

Finally, an extension of the model of maternal depression linked to youth romantic relationship quality tests a further corollary of the stress generation perspective: depression. Poor relationship quality is hypothesized to predict youth depression at age 20. Whisman and Bruce (1999) studied a large community sample and found that marital dissatisfaction predicted onset of major depression, and Whisman and Uebelacker (2006) reported that individuals in discordant relationships had higher levels of mood disorders, distress, and role impairment. Problematic romantic relationships are often a source of depression or other maladjustment in youth (e.g., Joyner & Udry, 2000; reviewed in Davila, Stroud, & Starr, 2009), perhaps especially for girls.

Overall, we expect to find support for a model of the intergenerational transmission of maternal depression and relational difficulties, such that maternal depression indirectly contributes to romantic relationship problems and depressive symptoms in early adulthood via the mechanisms proposed above. These hypotheses were tested via structural equation modeling in a large community sample of youth and families followed up to age 20, selected to represent varying levels and durations of maternal depression—including no depression—during the child’s life to age 15. Data were obtained from mothers, youth, and youth’s romantic partners. Although considerable evidence of gender differences in rates of depression exists, no a priori hypotheses were made regarding gender differences in the mechanisms represented in the model. However, gender differences will be examined on an exploratory basis.

Method

Participants

From a birth cohort study of health and behavioral outcomes of children (the Mater-University Study of Pregnancy; Keeping et al., 1989), 815 women were selected for varying histories of depression (or no depression) to be interviewed with their children at age 15 for a study of children of depressed women. A further follow-up was conducted when the youth turned 20 years old, and included 706 who were still available and consented. The current study is based on 182 of these youth (116 females, 66 males), who, at the time of the age 20 interview, had reported being involved in a committed, exclusive romantic relationship for a minimum of 3 months (mean duration 25.7 months, SD = 17.2 months) and whose partners provided information about the relationship. Youth (n = 182) reported a mean of 4.6 (SD = .6) on a scale of seriousness of the relationship ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very). Overall, 282 youth had reported being in committed relationships, but 76 of these cases did not have a participating partner, and 24 individuals were omitted from the sample due to missing data regarding maternal romantic relationships (largely due to mothers who were single when youth were 15).

To determine whether youth not being in a committed relationship was confounded with depression, the 282 youth who were in a committed relationship at 20 were compared with those not in steady romantic relationships on the age 15 predictor variables. There were no significant differences in the proportions who had depressed or nondepressed mothers (χ2(815) < 1, p = 0.59) or personal histories of depression diagnoses (χ2(815) < 1, p = 0.67). Significantly more females than males were in committed relationships at 20 (χ2(815) = 34.22, p < 0.001). There were no differences between those in or not in committed relationships at age 20, in terms of age 15 overall youth social functioning (t (813) = .69, p = 0.49), specific quality of mother-child relationship (t (812) = 1.13, p = 0.26), or mothers’ quality of relationship with her current intimate partner (t (812) = .19, p = 0.85). Thus, those who were in steady relationships at age 20 appear to be representative of the overall age 15 sample.

Similarly, comparisons between those with a participating partner (n = 206) and those in a relationship with a partner who did not participate (n = 76) indicated there were no significant differences on prior history of depression (χ2(258) < 1, p = 0.46) or maternal depression to age 15 (χ2(258) = .003, p = 0.96). Also, youth with a partner who did not participate (n = 76) did not report any differences in quality of the relationships on the LSI interview compared to those whose partners did participate, t (256) = .266, p = 0.79. The twenty-four participants excluded from final analyses due to insufficient maternal data did not differ from those included in final analyses (n = 182) on study variables pertaining to mother-child relationship, youth romantic relationship, or youth depression. However, omitted participants (n = 24) due to maternal missing data were more likely to have mothers with a history of depression compared to participants included in the final sample (χ2(206) = 11.94, p < 0.01).

The sample of 182 participants, consistent with the original birth cohort, was largely lower and lower-middle socioeconomic status, with 96% Caucasians and 70% of mothers married to the biological father of the youth at youth age 15. The mothers’ mean age at birth of the child was 24.8 years (S.D. = 5.1), and mothers’ median education was 10th grade. Comparisons between the original sample and those included in the current analyses indicated no significant differences on ethnicity, age at birth, or educational attainment.

Procedures

At youth age 15 and youth age 20, the child and mother underwent extensive interviewing and completed a series of questionnaires concerning child and mother psychopathology, youths’ and mothers’ chronic and acute stress exposure, and family interaction quality. At the age 20 interview, each youth was asked to invite his or her romantic partner to participate by completing questionnaires about themselves and the youth; those youth who did not wish to invite the romantic partner or who did not have a partner were asked to invite their best friend to complete the questionnaires about themselves and the youth. All interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes or other locations convenient for the participants and the interviewer; interviewers were blind to youth and mother depression status at age 15. Graduate students in psychology were trained to conduct and reliably score these interviews. Participants all gave informed consent, or assent in the case of minors, and the relevant institutional review/ethics panels approved the research protocols.

Measures

Maternal depression

Women were recruited for the study on the basis of scores on 4 assessments of depressive symptoms on the Delusions-States Symptoms Inventory (DSSI; Bedford & Foulds, 1977, 1978), a reliable and valid brief questionnaire that was administered during pregnancy, 3–5 weeks after birth of the child, at 6 months, and at 5 years after the birth. Scores were used to identify women likely to represent different levels of severity and chronicity of depression (or no depression). However, actual diagnostic status was assessed at the age 15 follow-up, based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) for current and lifetime disorders. The SCID is a well-validated and reliable semi-structured interview which covers the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for adult psychopathology. Interrater reliabilities for current and lifetime depression diagnoses were weighted kappas = 0.87 and 0.84, respectively. In the current study of 182 youth, maternal depression status was defined as a diagnosis of dysthymic disorder or (and) major depressive disorder during the youth’s lifetime by youth age 15 (n = 76 depressed, 106 never depressed). In all but one case the mother’s depression preceded that of the child.

Youth depression

History of major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder by age 15 was assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997). The K-SADS-PL is a well-validated and reliable semi-structured diagnostic interview that covers the DSM-IV criteria for current and lifetime child psychopathology. It was administered separately to the parent and the child at youth age 15 by trained clinical interviewers. Each diagnostic decision was reviewed by an independent clinical rating team based on all available information with diagnoses of depression given if either the youth or mother indicated criteria were met. Weighted kappas for current depressive disorders were 0.82, and 0.73 for past depressive disorders. Twenty-eight youth (of the current sample of 182) experienced a major depressive episode or dysthymic disorder by age 15; 154 were never depressed.

At ages 15 and 20, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was administered to participants. The BDI-II is a 21-item measure of depressive symptoms during the past two weeks. This measure is widely used and well validated. Cronbach’s alpha in the full sample of 20-year-olds was 0.93, suggesting strong internal consistency.

Assessment of mothers’ relationships with youth and partner

At youth age 15, mothers and youth were interviewed (separately) for chronic stress based on the semi-structured UCLA Life Stress Interview (e.g., Hammen et al., 1987; Hammen & Brennan, 2001), which covers acute stressors and chronic stress. The interview has been used and validated in a variety of adult, youth, and young adult samples (e.g., Adrian & Hammen, 1993; Rao, Hammen, & Daley, 1999; Hammen, Brennan, & Keenan-Miller, 2008). Probes ask about typical circumstances in the past 6 months across multiple domains, but only selected portions of the interview are relevant to the present study.

Each domain was scored by the interviewer on a 5-point scale with behaviorally specific anchors such that “1” represented superior functioning and circumstances, and 5 represented severely adverse conditions. For example, regarding mother’s relationship with the youth, a score of 2 indicates low chronic stress: presence of a good quality, close, confiding parental relationship with normal conflict, whereas 4 represents significant chronic stress with a frequently poor parent-child relationship marked by conflict and poor monitoring or control over the youth. Relevant to the current study, mothers completed sections of the LSI regarding their relationship with the target youth and their current romantic relationship functioning. At youth age 15, intraclass correlations of reliability were based on independent judge ratings: mothers’ relationship with youth, 0.82, mothers’ relationship with current partner, 0.88.

Mothers’ self-reported marital relationship quality at youth age 15 included the Satisfaction subscale of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; (Spanier, 1976). This scale has good levels of reliability and validity and is a useful measure of overall perceived relationship quality (Kurdek, 1992). In the full sample of 815, coefficient alpha was 0.93. Additionally, at the age 15 assessment, mothers completed a self-report version of the Modified Conflict Tactics Scale (MCTS; Pan, Neidig, & O’Leary, 1994) covering frequency of 7 items of psychological or physical coercion (argued heatedly; yelled/insulted; threw something; pushed, grabbed or shoved partner; tried to hit partner; hit partner). Coefficient alpha for the full sample was 0.92.

Assessment of youths’ relationships with mother and romantic partner

At youth age 15, the adolescent version of the Life Stress Interview for chronic stress domains included one domain relevant to relations with parents. From the age 20 Life Stress Interview, the domain concerning the youth’s relationship with romantic partner was also included in the present study. Intraclass correlations of agreement between independent raters were 0.84 for youth relations with parents at age 15 and 0.84 for youth relationship with romantic partner at age 20.

An additional youth-completed questionnaire at age 15 about the quality of relationship with the mother was the 10-item Psychological Control (versus psychological autonomy) scale of the revised Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schludermann & Schludermann, 1988). One example item inquires about the mother’s tendency to let the youth know everything she has done for him or her. Subscales of the CRPBI have been shown to have good reliability and validity (e.g., Safford, Alloy, & Pieracci, 2007). Coefficient alpha was 0.83.

At age 20, youth and their romantic partners independently completed the Satisfaction subscale of the DAS (Spanier, 1976). Coefficient alphas were 0.82 for youth and partner DAS.

Results

Proposed Mediation Model of Maternal Depression and Youth Romantic Outcomes

Descriptive statistics and bivariate or polychoric correlations among all observed variables are presented in Table 1. Consistent with study hypotheses, the authors sought to evaluate a structural model in which maternal depression portends risk for poor romantic relationship quality in offspring through three posited mechanisms: offspring depression, mother-child relationship discord, and mothers’ romantic relationship problems. Maternal depression and youth depression were both included in the proposed model as binary observed variables. Mother-child relationship discord, mothers’ romantic relationship problems, and youth romantic relationship quality were included in the model as latent factors with three continuous indicators each. The three indicators of maternal romantic relationship problems at youth age 15 were 1) maternal report of marital/intimate partner relationship conflict; 2) maternal report of relationship satisfaction on the DAS; and 3) maternal romantic relationship chronic stress, as assessed by the Life Stress Interview. The three indicators of mother-child discord at age 15 were: 1) youth-reported maternal psychological controlling behavior; 2) mother-child relationship chronic stress, as assessed by the Life Stress Interview with mothers as respondents; and 3) family relationship stress as assessed by the Life Stress Interview with participants as respondents. The three indicators of youth romantic relationship quality at age 20 were 1) youth-reported romantic relationship satisfaction on the DAS; 2) partner-reported romantic relationship satisfaction on the DAS; and 3) youth-reported romantic relationship stress on the LSI. All structural equation modeling analyses were conducted using Mplus version 6.1 (Múthen & Múthen, 1998–2010). All observed variables were converted to z-scores prior to conducting analyses for ease of interpretability.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Romantic Conflict | - | −.64** | .48** | .20** | .16* | −.03 | −.05 | −.16* | .21** | .24** | −.04 | .02 | .00 | .10 |

| 2. Maternal Romantic Satisfaction | - | −.66** | −.26** | −.20** | −.02 | −.12 | .20** | −.14 | −.35** | −.18* | .00 | −.21** | −.06 | |

| 3. Maternal Romantic Stress | - | .20** | .39** | .10 | −.13 | −.17* | .13 | .37** | .10 | −.02 | .17* | −.04 | ||

| 4. Youth Family Stress | - | .34** | .38** | −.21** | −.21** | .20** | .23** | .30** | .19* | .23** | −.06 | |||

| 5. Maternal Mother-Child Stress | - | .38** | −.11 | −.21** | .15 | .34** | .15* | .05 | .23** | −.13 | ||||

| 6. Maternal Control | - | −.03 | −.01 | .15 | .14 | .16* | .25** | .26** | −.12 | |||||

| 7. Youth Romantic Satisfaction | - | .46** | −.33** | −.06 | −.05 | −.11 | −.39** | .02 | ||||||

| 8. Partner Romantic Satisfaction | - | −.28** | .12 | −.11 | −.08 | −.15* | −.01 | |||||||

| 9. Youth Romantic Stress | - | −.24** | .07 | .00 | .29** | .04 | ||||||||

| 10. Maternal Depression | - | .23** | .05 | .19** | −.06 | |||||||||

| 11. Youth Depression Diagnosis | - | .21** | .27** | .10 | ||||||||||

| 12. Age 15 Depressive Symptoms | - | .34** | .20** | |||||||||||

| 13. Age 20 Depressive Symptoms | - | .13 | ||||||||||||

| 14. Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | - | |||||||||||||

| Means | 9.42 | 34.67 | 2.46 | 2.35 | 2.23 | 16.56 | 29.34 | 28.53 | 2.33 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 6.11 | 6.11 | - |

| (SD) | (1.91) | (4.53) | (0.74) | (0.54) | (0.44) | (3.98) | (3.35) | (3.80) | (0.72) | (0.50) | (0.36) | (6.54) | (7.19) | - |

p < .01,

p < .05

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To evaluate the factor structure of the nine proposed indicators of the three aforementioned latent factors, a confirmatory factor analysis was run employing maximum likelihood procedures. Fit statistics were mixed with respect to goodness of model fit (χ2(24) = 50.96, p < 0.01; comparative fit index = 0.93 [CFI; Hu & Bentler, 1999]; root mean square error of approximation = 0.08 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.05–0.11 [RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993]; standardized root mean square residual = 0.06 [SRMR; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010]). However, all observed variables loaded significantly onto their respective factors at p < 0.001. Standardized factor loadings ranged from |0.48| to |0.94|. Given the suboptimal model fit, researchers examined the modifications proposed by the Mplus program on the basis of a modification index greater than 10.00. Only proposed modifications supported by theoretical and methodological considerations were deemed acceptable for inclusion in the model. Accordingly, the researchers made one modification to the structural model, allowing the residuals of two observed indicators of separate latent factors, maternal romantic relationship chronic stress and mother-reported mother-child relationship chronic stress, to covary (Modification Index = 18.07; standardized Expected Parameter Change Index = 0.18). These two observed variables were obtained using the same semi-structured interview (the LSI), the same respondent (mothers), and the same trained interviewer for each participant, likely resulting in shared method variance. Thus, this modification was deemed methodologically justifiable. With this additional free parameter, the three-factor model proved a good fit to the data on the basis of all fit statistics (χ2(23) = 31.58, p = 0.11; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.045 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.00–0.08; SRMR = 0.05). All indicators loaded onto their respective factors at p < 0.001, and standardized factor loadings ranged from |0.48| to |0.96|. As expected, all three factors were moderately correlated. Mother-child relationship discord and maternal romantic relationship problems were correlated at r = 0.34, p < 0.001. Maternal romantic relationship discord and youth romantic relationship quality were negatively correlated at r = −0.26, p < 0.01. Mother-child relationship discord and youth romantic relationship quality were negatively correlated at r = −0.40, p < 0.001. These findings provide support for the inclusion of three distinct, but related, latent factors in the proposed models.

Maternal Depression and Youth Romantic Relationship Quality

After establishing support for the three latent factors to be included in the mediation model, structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood procedures was employed to evaluate a model in which maternal depression directly predicts poor romantic relationship quality in offspring. In this model, the aforementioned latent factor indexing romantic relationship quality was included as the outcome variable. Gender was additionally included as a covariate in this model. Analyses yielded support for a model in which maternal depression predicts romantic relationship quality, controlling for gender. The model was an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 (4) = 6.94, p = 0.14; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.06 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.00–0.13; SRMR = 0.03). Most importantly, even after controlling for the effect of gender on relationship quality, maternal depression was a significant predictor of the latent factor indexing romantic relationship quality (β = −0.25, SE = 0.09, z = −2.71, p < 0.01).

Multiple Mediation Analysis

Given the significant effect of maternal depression on a latent factor of romantic relationship quality, the proposed multiple mediation model was evaluated. This model included a direct path from maternal depression to a latent factor representing youth romantic relationship quality as well as three indirect pathways of this association. The three putative mediators were mother-child relationship discord, maternal romantic relationship problems, and youth depression history. The residuals of all three mediators were allowed to covary in accordance with standard guidelines for multiple mediation employing structural equation modeling techniques (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Gender was included in the model as a covariate.

Due to the presence of one binary categorical mediator and several non-normal continuous indicators of latent factors, robust weighted least squares procedures were employed. Missing data was accounted for using maximum likelihood estimation based on observed covariates, consistent with standard procedures used with the WLSMV estimator in Mplus (see Múthen & Múthen, 1998–2010). Bias-corrected bootstrapping procedures (2000 replications) were implemented to obtain more accurate confidence intervals around parameter estimates and estimates of indirect effects when testing for mediation (see Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007).

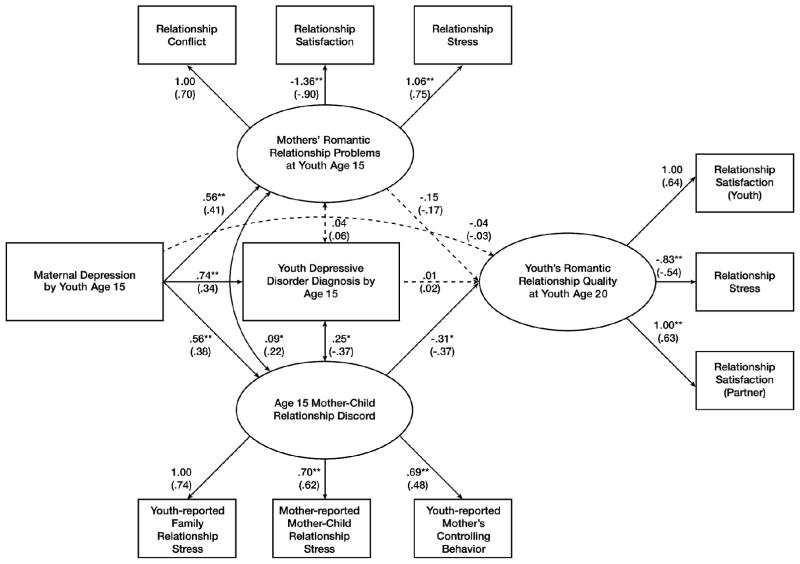

Fit indices suggested that the model was an excellent fit to the data. The comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.96 and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.04 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.00–0.07. The chi-square test statistic was nonsignificant (χ2 (41) = 55.72, p = 0.06). All indicators of the three latent constructs represented in the model, mothers’ romantic relationship problems, mother-child discord, and youth romantic relationship quality, loaded significantly onto their respective factors at p < 0.01. Standardized factor loadings ranged from |0.48| to |0.90|. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Multiple mediation model with unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients in parentheses. **p < .01, *p < .05. Paths that were nonsignificant are represented by dotted lines. While gender was included in this model as a covariate, with paths to all three mediators and the outcome variable, it was nonsignificantly related to all variables and was excluded from the figure for ease of readability. The error variances of mother-reported romantic relationship stress and mother-reported mother-child relationship stress were also allowed to covary and were significantly correlated, but were also excluded from the figure for ease of readability.

With the three mediators included in the model, maternal depression no longer exerted a significant direct effect on youth romantic relationship quality (B = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.38, 0.32]). However, as hypothesized, maternal depression significantly predicted mothers’ romantic relationship problems (B = 0.56, 95% CI [0.34, 0.86]), youth depression diagnosis (B = 0.74, 95% CI [0.25, 1.21]), and mother-child relationship discord (B = 0.56, 95% CI [0.34, 0.83]). Youth romantic relationship quality was significantly predicted by mother-child discord ((B = −0.31, 95% CI [−0.67, −0.05]). However, neither mothers’ romantic relationship problems (B = −0.15, 95% CI [−0.40, 0.03]) nor youth depression history (B = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.23]) significantly predicted youth romantic relationship quality in this model. (Note that all 95% confidence intervals containing 0 are not significant at the p < 0.05 level, while confidence intervals that do not contain 0 are significant at the p < 0.05 level. Unstandardized estimates and confidence intervals are reported.)

Given that mother-child discord was significantly predicted by maternal depression and was a significant predictor of youth romantic relationship quality, a specific mediated effect was examined using the bias-corrected bootstrapping method for testing the significance of indirect effects (Fritz & McKinnon, 2007). Analyses confirmed that mother-child discord was a significant mediator of the relationship between maternal depression and youth romantic relationship quality (estimate = −0.17, 95% CI [−0.44, −0.04]) when assessed simultaneously with the other hypothesized mediated effects.

Depressive Outcome Model

Given that mother-child discord was found to be a significant mediator of the relationship between maternal depression and youth romantic relationship quality, a second structural model was evaluated to assess whether mother-child discord during adolescence portends risk for age 20 youth depressive symptoms and whether poor romantic relationship quality serves as a mediator of this relationship, controlling for age 15 depressive symptoms. Gender was also included in this model as a covariate. Bias-corrected bootstrapping methods (2000 replications) were employed to obtain confidence intervals for parameter estimates and indirect effects.

Fit statistics indicated that the model was an acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.01–0.09, SRMR = 0.04). The chi-square test was significant (χ2(21) = 33.21, p = 0.04). All indicators loaded significantly onto their respective factors with standardized factor loadings ranging from |0.49| to |0.79|, p < 0.01.

Analyses revealed that, consistent with the findings of the first tested model, age 15 mother-child discord significantly predicted later youth romantic relationship quality (B = −0.35, 95% CI [−0.94, −0.07]). In turn, youth romantic relationship quality significantly predicted concurrent youth depressive symptoms (B = −0.49, 95% CI [−1.09, −0.21]). A test of the indirect effect confirmed that youth romantic relationship quality was a significant mediator of the relationship between mother-child discord and age 20 youth depressive symptoms, controlling for earlier depressive symptoms (estimate = 0.17, 95% CI [0.03, 0.74]). Notably, the direct effect from mother-child discord to youth depressive symptoms at age 20 was not significant in this model (B = 0.34, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.73]).

Full Intergenerational Transmission Model

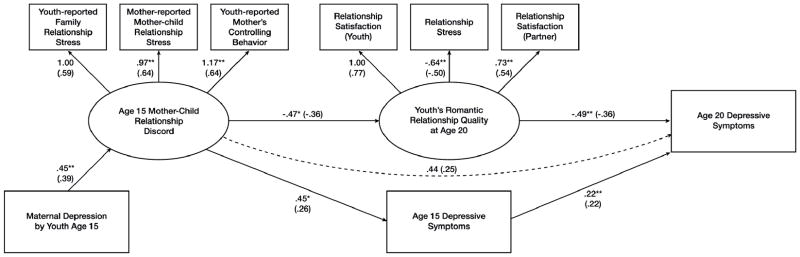

Following from the significant findings of the multiple mediation model and the depressive outcome model, a final model was tested in which maternal depression predicts mother-child relationship difficulties, which portends risk for offspring’s romantic relationship difficulties, and, in turn, depressive symptoms. Consistent with the previous models, bias-corrected bootstrapping methods with 2000 replications were employed. Gender and age 15 depressive symptoms were included as controls.

Fit statistics were as follows: χ2(25) = 47.59, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.07 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.04–0.10. Such fit indices suggest that the model was a suboptimal fit to the data. To improve model fit, several nonsignificant pathways with standardized Betas less than |0.1| were omitted. These included the paths from 1) maternal depression to youth depressive symptoms at age 15; 2) maternal depression to youth depressive symptoms at age 20; and 3) maternal depression to youth romantic relationship quality. Such changes improved model fit such that χ2(28) = 48.51, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.06, with a 90% confidence interval of 0.03–0.09. Given this improvement in the RMSEA to the cutoff for acceptable model fit, the SRMR < 0.08, and the increase in CFI (though not to standards of excellent fit), the revised model can be considered an adequate fit to the data. See Figure 2 for the final model.

Figure 2.

Intergenerational transmission model with unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients in parentheses. **p < .01, *p < .05. Paths that were nonsignificant are represented by dotted lines. While gender was included in this model as a covariate, it was excluded from the figure for ease of readability

Similar to the aforementioned models, maternal depression significantly predicted mother-child relationship discord (B = 0.45, 95% CI [0.24, 0.68]), mother-child relationship discord significantly predicted youth romantic relationship quality (B = −0.47, 95% CI [−0.78, −0.14]), and youth romantic relationship quality was inversely related to age 20 depressive symptoms (B = −0.49, 95% CI [−1.07, −0.20]). Finally, support was found for an indirect effect from maternal depression to depressive symptoms through mother-child discord and romantic relationship quality (estimate = 0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.33]). Notably, this pattern of significant findings was consistent with model results before nonsignificant pathways were eliminated.

Gender Moderation

Multiple group analysis was employed to test for gender differences. As a first step, the three-factor model included in the confirmatory factor analysis was tested for strict measurement invariance across groups. A model in which all parameters were free to vary across genders was compared to a model in which factor loadings, intercepts, residuals, factor means, and error variances were constrained to be equal across groups. Chi-square difference testing revealed no significant difference in fit between models (χ2diff = 30.39, dfdiff = 24, p = 0.17).

For all models, chi-square difference testing was used to determine whether model fit was significantly degraded when all paths were constrained to be equal across genders as opposed to allowing the paths to vary across genders. Gender differences in mediated pathways were then examined by testing for significant differences in indirect effect point estimates between males and females. Across all three models, no significant differences were found between the more restrictive and less restrictive models in terms of model fit. Additionally, no indirect effects were significantly different between genders. Thus, analyses revealed no moderation by gender in terms of overall model fit or specific mediated pathways.

Discussion

The current study explored both psychosocial (i.e. functioning in romantic relationships) and depressive outcomes in the 20-year-old offspring of women with and without histories of depression. It was expected that maternal depression would influence youth romantic relationship functioning both directly and indirectly through mother-child relationship discord, mothers’ own romantic relationship difficulties, and youth depression diagnoses. Consistent with study hypotheses, maternal depression predicted greater difficulties in youth romantic relationships, as indicated by youth-reported and partner-reported relationship satisfaction and relationship chronic stress. Importantly, tests of a multiple mediation model revealed that this effect of maternal depression was mediated by discord in the mother-child relationship at age 15. However, neither mothers’ romantic relationship problems nor youth depression status were predictive of youth romantic relationship dysfunction at age 20 in the tested model.

Given that mother-child relationship discord significantly predicted poor romantic relationship quality among youth, a second model was tested to determine whether mother-child discord indirectly conferred risk for age 20 depressive symptoms, as mediated by its effects on romantic relationship quality. Support was found for this hypothesis. Notably, these effects of mother-child discord were found even controlling for youths’ concurrent depressive symptoms at age 15, suggesting that the long-term maladaptive consequences are likely due to the relational impairment itself, as opposed to related depressive symptoms.

When maternal depression was added in a final full model that assessed for the intergenerational transmission of relationship difficulties and depression, a significant indirect effect was found whereby maternal depression predicted mother-child discord, which led to poorer quality romantic relationships, and, in turn, age 20 depressive symptoms.

The results are consistent with an interpersonal perspective on risk factors for, and consequences of, depression, that emphasizes the dysfunctional interpersonal styles that may give rise to stress-inducing behaviors and depressive consequences (e.g., Hammen et al., 2004; Joiner & Timmons, 2009). In the current study, we hypothesized that one mechanism of the risk for maladaptive outcomes in offspring of depressed mothers is exposure to negative quality family relationships and potentially poor role models for selection into and management of adaptive intimate relationships. While the maladaptive consequences of poor romantic role models were not supported by the current study, study findings suggest that a negative mother-child relationship may be especially detrimental in setting the stage for maladaptive intimate relationships during the transition to adulthood. This finding follows from research suggesting that positive features of the mother-child relationship, such as nurturance and supportiveness, are important in the promotion of positive youth romantic relationships (Conger, Cui, Bryant, & Elder, 2000; Donnellan, Larsen-Rife, and Conger, 2005; Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002). Just as positive parenting characteristics predict youths’ later positive romantic relationships, negative parent-child relationships appear to translate into youths’ relational difficulties and romantic stress that also portend depression.

The mediating role of maternal romantic relationship difficulties was not supported, in contrast with the body of research on intergenerational transmission of marital/intimate partner discord (Amato & Booth, 2001; Cui, et al., 2010; Hare, et al., 2009). Further research may need to capture maternal marital difficulties throughout the youth’s early life, rather than at one time point during youth adolescence, to determine whether this is a mechanism in the relationship between maternal depression and youth relationship difficulties.

Youth history of depression by 15 was also hypothesized to predict youths’ own romantic relationship quality at 20 and mediate the effects of maternal depression, but it, too, was not significant. Although the current study found no effect of depression history on romantic relationship status, it is possible that some youth with significant histories of depression may have had recent, but not current, poor quality romantic relationships that were not captured by the timing of assessments. Future research may benefit from examining romantic relationship quality among individuals with a history of depression over a longer time frame. Future research should also take into account severity and frequency of depression to better understand the role these factors play in prospective risk for romantic relationship difficulties.

Analyses indicated no gender differences in any of the models or mediated pathways, suggesting that the associations among variables are similar for males and females. However, it should be noted that samples sizes of 66 males and 116 females may have limited power to detect differences in the model. These models should be tested in larger samples to allow for more definitive statements on the presence or absence of gender differences in the interpersonal and psychopathological risk conferred by maternal depression and its concomitants.

The results extend the findings of studies of children of depressed mothers beyond the youths’ risk for depression and psychopathology to underscore the comparatively poorer quality intimate partnerships even with currently committed relationships at age 20. Such difficulties portend risk for depressive symptoms and imply the possibility of future discord and disruption, although further follow-ups are needed to characterize the actual relationship course and long-term clinical consequences. It has often been speculated that much of the risk for youths’ depression outcomes operates through impaired parenting in addition to genetic mechanisms. The current study further suggests that maternal psychopathology and subsequent mother-child relationship discord also contribute to adverse functional outcomes, in this case difficult or less satisfying romantic relationships, that seem to serve as an intermediate step in the propagation of depression through the generations. Such patterns imply that efforts to mitigate the effects of maternal depression on children may require intervention at the level of parent-child relationship quality as well as at the level of youths’ own attitudes, expectations, and behaviors to help youth sustain and nurture close relationships, and deal effectively with others when problems arise. Interventions aimed at interpersonal functioning may not only be beneficial for promoting the formation and maintenance of healthy relationships, but as a preventative measure for curbing the onset of depressive symptoms.

The present study had several strengths, including a longitudinal design following youth into the transition to adulthood when intimate relationship-building is a particularly salient developmental task, use of multiple informants including romantic partners, a relatively large sample of intimate relationships representative of the overall population of this study, diagnostic evaluations to characterize the youth and their mothers, and structural equation modeling which reduces measurement error. Limitations must also be noted. The sample was limited to those currently in committed relationships and to those with partners willing and able to participate. There is reason to suspect that the current findings represent a relatively conservative test of hypotheses in two senses. Though youth in relationships whose partners did not participate did not have significantly higher levels of current relationship stress, the sample may have excluded some more discordant couples. Similarly, the exclusion of participants whose mothers did not provide sufficient data regarding their own romantic relationships, largely due to being single at the time of the interview, eliminated some mothers who may have been more severely impaired, both in terms of depression history as well as the ability to create and maintain intimate relationships. Moreover, the full impact of youth depression on relationships might be diluted if more impaired youth were not currently in a steady relationship. However, there were no differences in depression histories between those in steady relationships and all other youth in the study. Additionally, mothers’ romantic relationship quality at youth age 15 might have underestimated marital conflict and its impact in cases where mothers were no longer married to the previous partner who in many cases was the father of the youth.

The use of categorical measures of maternal and youth depression by age 15 may be considered both a strength and a limitation. While the use of diagnostic status allows for a better understanding of the correlates and consequences of clinically significant depression, such binary measures do not capture subthreshold, but clinically relevant, depressive symptomatology. In this way, tests in the current study may be overly conservative and limited.

Unfortunately, due to the limited number of participants involved in committed relationships at age 15, romantic relationship quality in adolescence could not be included in the model as an autoregressive control. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that adolescent romantic relationship quality was confounded with mother-child relationship discord in the prediction of age 20 romantic relationship quality. However, age 15 depressive symptoms were included as an autoregressive control in the models predicting age 20 depressive symptoms. Thus, mother-child discord during adolescence appears to portend risk for depressive symptoms during young adulthood over and above the risk conferred by adolescent depressive symptoms.

It is important to note that the youth-reported measure of parent-child relationship quality did not specifically separate relations with the mother and father when both were present in the family, possibly obscuring unique effects of fathers. Effects of paternal depression were also not included in the model, but this is an important gap that should be addressed in future studies.

In summary, children of depressed mothers who are now in committed romantic relationships carry on the unfortunate pattern of the relationship difficulties that their mothers experienced in their marital and parenting roles. In turn, the intergenerational transmission of discord represents another contributor to youth risk for depression as young adults. Finding ways to break this intergenerational cycle is a challenge for treatment and intervention but may reap crucial benefits not only to the youth but also to their future families.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Mater Misericordiae Mothers’ Hospital in Queensland, Australia, and the National Institute of Mental Health grant R01 MH52239. We thank project coordinators, Robin LeBrocque, Cheri Dalton Comber, and Sascha Hardwicke, and the many members of the MUSP, M900, and M20 research teams, and gratefully acknowledge Jake Najman, William Bor, Michael O’Callaghan, and Gail Williams, principal investigators of the original Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy.

Contributor Information

Shaina J. Katz, University of California, Los Angeles

Constance L. Hammen, University of California, Los Angeles

Patricia A. Brennan, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

References

- Adrian C, Hammen C. Stress exposure and stress generation in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:354–359. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato P, Booth A. The legacy of parents’ marital discord: Consequences for children’s marital quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:627–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford A, Foulds G. Validation of the delusions-symptoms-states inventory. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1977;50:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1977.tb02409.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford A, Foulds G. Delusions-symptoms-states inventory of anxiety and depression. Windsor, England: NFER; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JS, Garber J. Predictors of the first onset of a major depressive episode and changes in depressive symptoms a cross adolescence: Stress and negative cognitions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:779–796. doi: 10.1037/a0025441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant CM, Elder GH., Jr Competence in early adult romantic relationships: a developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Thompson R, Palmer SC. Marital quality, coping with conflict, marital complaints, and affection in couples with a depressed wife. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(1):26–37. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Durtschi J, Donnellan M, Lorenz F, Conger R. Intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:688–697. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Hall T, Bradbury TN. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: Within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:557–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Stroud CB, Starr LR. Depression in couples and families. In: Gotlib I, Hammen C, editors. Handbook of Depression. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 467–491. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD. Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:562–576. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart N, Hammen C. Interpersonal style, stress, and depression: An examination of transactional and diathesis-stress models. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:23–38. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73:241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S, Rouse M, Connell A, Broth M, Hall C, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib I, Lewinsohn P, Seeley J. Consequences of depression during adolescence: Marital status and marital functioning in early adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:686–690. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. The generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Children of depressed parents. In: Gotlib I, Hammen C, editors. Handbook of depression. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Adrian C, Gordon D, Burge D, Jaenicke C, Hiroto D. Children of depressed mothers: Maternal strain and symptom predictors of dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:190–198. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.96.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: Tests of an interpersonal impairment hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(2):284–294. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA, Keenan-Miller D. Patterns of adolescent depression to age 20: the role of maternal depression and youth interpersonal dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan P, Le Brocque R. Youth depression and early childrearing: Stress generation and intergenerational transmission of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:353–363. doi: 10.1037/a0023536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih J. Stress generation and depression. In: Dobson KS, Dozois DJA, editors. Risk factors in depression. London: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 409–428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih J, Brennan P. Intergenerational transmission of depression: Test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:511–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare A, Miga E, Allen J. Intergenerational transmission of aggression in romantic relationships: The moderating role of attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:808–818. doi: 10.1037/a0016740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Timmons KA. Depression in its interpersonal context. In: Gotlib I, Hammen C, editors. Handbook of Depression. 2. New York: Guilford Publications; 2009. pp. 322–339. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Udry JR. You don’t bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:369–91. doi: 10.2307/2676292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for school-age children – present and lifetime version (KSADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeping JD, Najman JM, Morrison J, Western JS, Andersen MJ, Williams GM. A prospective longitudinal study of social, psychological, and obstetrical factors in pregnancy: Response rates and demographic characteristics of the 8,556 respondents. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;96:289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Dimensionality of the dyadic adjustment scale: Evidence from heterosexual and homosexual couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 1992;6(1):22–35. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.6.1.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen JA, Solantaus TS, Punamaki R-L. Parental mental health and children’s adjustment: The quality of marital interaction and parenting as mediating factors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:227–241. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.t01-1-00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Olino TM, Klein DN. Psychosocial impairment in offspring of depressed parents. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(10):1493–1503. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy CM, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. In: England MJ, Sim LJ, editors. Committee on depression, parenting practices, and the healthy development of children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Neidig P, O’Leary KD. Male-female and aggressor-victim differences in the factor structure of the Modified Conflict Tactics Scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1994;9:366–382. doi: 10.1177/088626094009003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Hammen C, Daley S. Continuity of depression during the transition to adulthood: A 5-year longitudinal study of young women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:908–915. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Pieracci A. A comparison of two measures of parental behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(3):375–384. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9092-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schludermann S, Schludermann E. Unpublished manuscript. University of Manitoba; Winnipeg, Canada: 1988. Shortened Child Report of Parent Behavior Inventory (CRPBI-30): Schludermann Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Shih J, Abela J, Starrs C. Cognitive and interpersonal predictors of stress generation in children of affectively ill parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9267-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1976;38(1):15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vujeva H, Furman W. Depressive symptoms and romantic relationship qualities from adolescence through emerging adulthood: A longitudinal examination of influences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:123–135. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Bruce ML. Marital dissatisfaction and incidence of major depressive episode in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:674–678. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA. Impairment and distress associated with relationship discord in a national sample of married or cohabiting adults. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:369–377. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA, Weinstock LM. Psychopathology and marital satisfaction: The importance of evaluating both partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:830–838. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]